Abstract

Recent work has demonstrated pro-oncogenic functions of the transcription factor CCAAT box/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) in various tumors, implicating C/EBPβ as an interesting target for the development of small-molecule inhibitors. We have previously discovered that the sesquiterpene lactone helenalin acetate, a natural compound known to inhibit NF-κB, is a potent C/EBPβ inhibitor. We have now examined the inhibitory mechanism of helenalin acetate in more detail. We demonstrate that helenalin acetate is a significantly more potent inhibitor of C/EBPβ than of NF-κB. Our work shows that helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ by binding to the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ, thereby disrupting the cooperation of C/EBPβ with the co-activator p300. C/EBPβ is expressed in several isoforms from alternative translational start codons. We have previously demonstrated that helenalin acetate selectively inhibits only the full-length (liver-enriched activating protein* (LAP*)) isoform but not the slightly shorter (LAP) isoform. Consistent with this, helenalin acetate binds to the LAP* but not to the LAP isoform, explaining why its inhibitory activity is selective for LAP*. Although helenalin acetate contains reactive groups that are able to interact covalently with cysteine residues, as exemplified by its effect on NF-κB, the inhibition of C/EBPβ by helenalin acetate is not due to irreversible reaction with cysteine residues of C/EBPβ. In summary, helenalin acetate is the first highly active small-molecule C/EBPβ inhibitor that inhibits C/EBPβ by a direct binding mechanism. Its selectivity for the LAP* isoform also makes helenalin acetate an interesting tool to dissect the functions of the LAP* and LAP isoforms.

Keywords: adipocyte, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP), E1A-binding protein p300 (P300), inhibitor, NF-kappa B (NF-KB), small-molecule, helenalin acetate

Introduction

The CCAAT box/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ),2 a highly conserved member of the family of basic-region leucine zipper transcription factors, is involved in the control of differentiation and proliferation of various cell types, including adipocytes, keratinocytes, mammary epithelial cells, and myelomonocytic cells (1, 2). In accordance with its multiple roles, the activity of C/EBPβ is highly regulated on the transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional levels. Based on alternative translation initiation, the C/EBPβ mRNA is translated into several isoforms of C/EBPβ, two of which (LAP* and LAP) function as transcriptional activators, whereas the third isoform (liver-enriched inhibitory protein (LIP)) is a transcriptional inhibitor (3–5). The full-length isoform of C/EBPβ (LAP*) and the slightly shorter LAP isoform differ by only 21 N-terminal amino acids, whereas LIP lacks most of the N-terminal sequences that harbor the transactivation domain. The relative expression levels of the different isoforms are controlled by short upstream open reading frames, and their deregulation has been implicated in tumor development, for example of breast cancer (5–7). In addition to the differential isoform expression, C/EBPβ is regulated by various post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation (8–10), acetylation (11–13), methylation (14, 15), and sumoylation (16).

Recent work has shown that deregulation of C/EBPβ plays a crucial role in the development of certain tumors. Increased expression of C/EBPβ has been demonstrated in tumors of the colon, kidney, stomach, prostate, and the ovaries (6, 17–19). In many cases, high C/EBPβ expression correlates with increased malignancy and invasiveness of the tumor cells. In glioblastoma, high C/EBPβ expression correlates with a poor prognosis (20–22) and, together with STAT3, plays a key role in establishing a mesenchymal gene expression signature that is responsible for the aggressiveness of high-grade glioblastomas (23). In the hematopoietic system, C/EBPβ plays pro-oncogenic roles in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) (24, 25), where C/EBPβ has been identified as a crucial downstream target of oncogenic anaplastic lymphoma kinase signaling. Finally, our own work has recently suggested a pro-oncogenic role of C/EBPβ, possibly in conjunction with c-Myb, in acute myeloid leukemia (26). C/EBPβ is therefore emerging as an interesting target for the development of small-molecule inhibitors.

We have recently identified the sesquiterpene lactone helenalin acetate, a natural compound from Arnica montana, as the first highly active small-molecule inhibitor of C/EBPβ (26). The initial characterization of its inhibitory activity has shown that helenalin acetate inhibits the LAP* isoform but not the LAP isoform of C/EBPβ or the related transcription factor C/EBPα, and that helenalin acetate exerts anti-proliferative effects in acute myeloid leukemia cells but not in normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Overall, these findings have suggested that small-molecule C/EBPβ inhibitors might have therapeutic potential. Here, we have examined the inhibitory mechanism of helenalin acetate in more detail. We show that helenalin acetate binds to the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ and thereby disrupts its cooperation with the co-activator p300. Interestingly, helenalin acetate does not bind to the LAP isoform, explaining why it is not inhibited by helenalin acetate.

Results

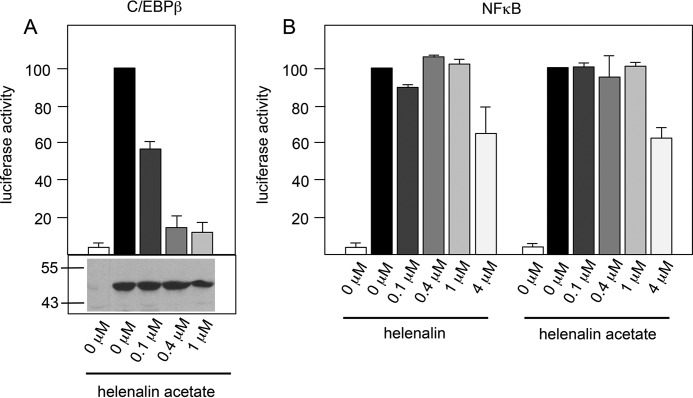

Helenalin Acetate Is a Potent Small-molecule Inhibitor of C/EBPβ

Helenalin and its acetate ester helenalin acetate have anti-inflammatory activities and were previously shown to inhibit the transcription factor NF-κB, a key regulator of inflammation (27, 28). It is therefore thought that the anti-inflammatory activities of helenalin and its derivatives are due to their ability to inhibit the activity of NF-κB. We have recently identified helenalin acetate as the first highly potent small-molecule inhibitor of C/EBPβ (26). That helenalin acetate targets NF-κB as well as C/EBPβ prompted us to compare its inhibitory activity for both transcription factors, in particular because C/EBPβ has also been implicated in inflammatory processes (29). Because our previous work has focused on chicken C/EBPβ, we first assessed the effect of helenalin acetate on human C/EBPβ, using reporter experiments with an expression vector for human C/EBPβ and a C/EBPβ-responsive luciferase reporter gene. Similar to the inhibition of chicken C/EBPβ, sub-micromolar concentrations of helenalin acetate strongly inhibited the activity of human C/EBPβ (Fig. 1A). Western blotting confirmed that the inhibition was not caused by decreased amounts of C/EBPβ. To monitor the activity of NF-κB, we measured the TNFα-dependent stimulation of a luciferase reporter gene that contains several NF-κB sites (Fig. 1B). Helenalin and helenalin acetate showed partial inhibitory effects at concentrations of 4 μm. We estimated the EC50 concentrations for the inhibition of NF-κB to lie between 4 and 5 μm for both compounds, in accordance with published data (30). These experiments show that the concentrations necessary to inhibit the two transcription factors differ by a factor of 10 or more, clearly demonstrating that helenalin acetate is a significantly more potent inhibitor of C/EBPβ than of NF-κB.

FIGURE 1.

Helenalin acetate is a more potent inhibitor of C/EBPβ than of NF-κB. A, QT6 fibroblasts were transfected with the C/EBP-inducible luciferase reporter gene p-240luc, pCMVβ, and expression vectors for human C/EBPβ. Cells were treated for 12 h with the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate and then analyzed for luciferase activity. The columns show the average luciferase activity normalized against the β-galactosidase activity. Error bars show the S.D. Aliquots of the cell extracts were used to visualize the amounts of C/EBPβ by Western blotting (bottom panel). Numbers on the left side refer to molecular weight markers. B, Hek293T cells transfected with the NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter gene pGL2-6×NFκB-luc and pCMVβ were treated with 10 μg/ml TNFα and the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate or helenalin. Cells were analyzed as in panel A.

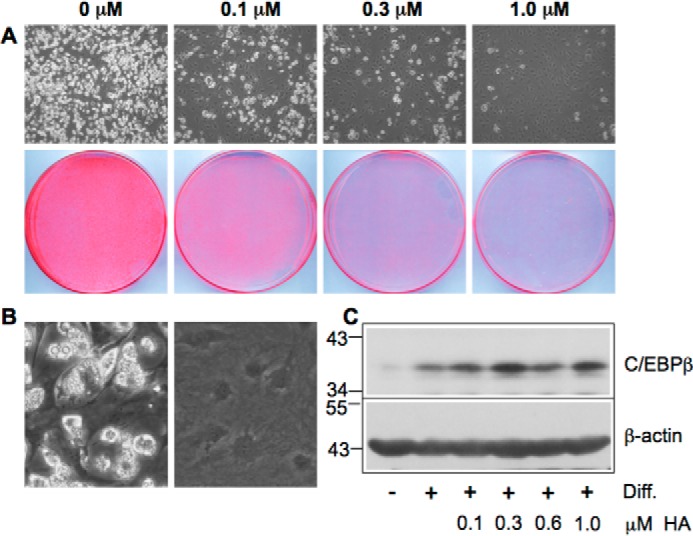

We also examined the effect of helenalin acetate on the conversion of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes into fat cells as a well characterized model of a physiological C/EBPβ-dependent differentiation process (31, 32). A number of studies have established that C/EBPβ plays a key role in the initiation of the 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation program by inducing a cascade of gene activations, leading to fat cells, which are characterized by the appearance of lipid droplets in the cytoplasm. In the light microscope, these droplets appear as bright structures in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A, top panels). Fig. 2A shows that 0.1 μm helenalin acetate already inhibited the differentiation significantly, whereas 1 μm resulted in virtually complete inhibition, as assessed by microscopic inspection of the cells and by staining with the lipid dye Oil-Red-O. This result is in accord with helenalin acetate being a potent inhibitor of C/EBPβ. Fig. 2B shows differentiated cells at higher magnification, demonstrating the presence of lipid drops in the cytoplasm, which appear as bright vesicles. As shown by the Western blots in Figs. 1A and 2C, the inhibition of C/EBPβ by helenalin acetate was not accompanied by a decrease of the amount of C/EBPβ, indicating that the activity and not the expression of C/EBPβ is inhibited.

FIGURE 2.

Helenalin acetate inhibits adipocyte differentiation. A, 3T3-L1 cells were induced to differentiate for 7 days in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate. The top panels show microscopic pictures of the cells at low magnification with differentiated cells appearing white due to the presence of lipid drops in the cytoplasm. The bottom panels show staining of the cells with Oil-Red O. The same number of cells was plated in each case. B, microscopic pictures of differentiated and undifferentiated 3T3-L1 cells at higher magnification. C, Western blotting analysis of C/EBPβ and β-actin expression in undifferentiated (−) and differentiated (+) 3T3-L1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate. Numbers on the left refer to molecular weight markers. Diff., differentiation.

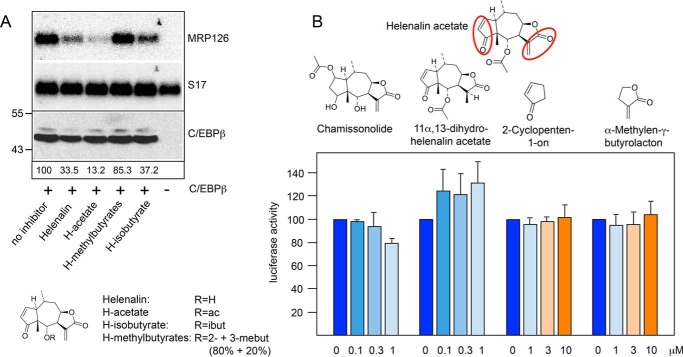

The Presence of Reactive Groups Is Not Sufficient to Explain the Inhibitory Activity of Helenalin Acetate on C/EBPβ

To gain insight into the structural features of helenalin acetate that contribute to its inhibitory activity, we first examined the activity of helenalin and several ester derivatives of helenalin. As a read-out of C/EBPβ activity, we analyzed the expression of the endogenous C/EBP-inducible MRP126 gene by Northern blotting, using S17 mRNA as a loading control. The MRP126 gene is not expressed in fibroblasts; however, its expression is induced when the cells are transfected with an expression vector for C/EBPβ (10, 26). Analysis of the increase of MRP126 mRNA levels caused by C/EBPβ expression is therefore a convenient method to assess the activity of C/EBPβ. In Fig. 3A, the induction of MRP126 expression by C/EBPβ is evident by comparing MRP126 expression in the first and last lane. The other lanes in Fig. 3A illustrate the inhibitory effects of helenalin and different helenalin esters on C/EBPβ activity. Helenalin acetate was the most potent C/EBPβ inhibitor of these compounds. Helenalin was only slightly less active, whereas the inhibitory activities of helenalin isovalerate and helenalin 2- and 3-methyl butyrates were significantly lower. Notably, the amount of C/EBPβ (shown in Fig. 3A, bottom panel) was not significantly affected by any of the compounds.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibitory activities of different sesquiterpene lactones. A, QT6 cells were transfected with expression vector for chicken C/EBPβ and treated with 1 μm of the indicated helenalin esters or left untreated, as indicated below the lanes. The last lane shows untransfected cells, which serve as control. Cells were harvested after 12 h and analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of MRP126 and S17 mRNAs (top and middle panel) and by Western blotting for the expression of C/EBPβ (bottom panel). Numbers below the lanes indicate the relative amounts of MRP126 mRNA determined by quantification with a phosphor image analyzer. ac, acetate; ibut, isobutyrate; mebut, methylbutyrate. B, the structure of helenalin acetate is shown at the top. Reactive α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups are marked with red circles. The structures of chamissonolide, 11α,13-dihydrohelenalin acetate, 2-cyclopenten-1-one and α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone are shown below. Reporter assays were performed with QT6 fibroblasts transfected with the C/EBP-dependent luciferase reporter gene p-240luc, expression vector for chicken C/EBPβ and pCMVβ. Cells were cultivated for 12 h with the indicated concentrations of the compounds shown above and analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities as in Fig. 1. Error bars show the S.D.

Helenalin acetate contains two α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups that are highlighted in Fig. 3B. These electrophilic groups are known to undergo Michael-type addition reactions with nucleophiles, such as the thiol groups of cysteine residues, leading to the formation of covalent adducts (33, 34). For example, helenalin and helenalin acetate have been shown to inhibit the DNA binding activity of transcription factor NF-κB by covalent modification of Cys-38 of the p65 subunit of NF-κB (27, 28). To address the relevance of these reactive groups for the inhibition of C/EBPβ, we examined the inhibitory potential of two related sesquiterpene lactones, chamissonolide and 11α,13-dihydrohelenalin acetate, each of which lack one of the reactive groups of helenalin acetate, as shown by the comparison of their structures. Both compounds were virtually inactive when compared with helenalin acetate (Fig. 3B), strongly suggesting that the inhibitory activity of helenalin acetate might depend on the presence of both reactive groups. However, that the presence of the reactive groups alone cannot explain the inhibitory activity of helenalin acetate is demonstrated by the fact that even high concentrations (up to 10 μm) of cyclopentene-1-one and α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone, each of which corresponds to one of the reactive partial structures of helenalin acetate, had no inhibitory effect at all (Fig. 3B). Because of the presence of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups, both compounds have an inherent ability to react with nucleophilic groups to undergo Michael-type addition reactions, well known in organic chemistry. We also combined both compounds to mimic helenalin acetate, but even at the highest concentration (10 μm each), no inhibition was observed (data not shown). Thus, it appeared that the specific spatial structure of helenalin acetate and the correct relative orientation of the two enone groups are important for its inhibitory activity and that the presence of these reactive groups alone cannot account for its ability to inhibit the activity of C/EBPβ. This is also supported by the comparison of the inhibitory activity of helenalin and mexicanin-I. We have previously shown that the inhibitory activity of helenalin is significantly higher than that of mexicanin-I (26). Both compounds are stereoisomers, which means that they both have the same reactive groups in a slightly different three-dimensional framework. The fact that their inhibitory activities differ strongly underlines the notion that the specific spatial structures of these molecules rather than the mere presence of reactive groups determines their inhibitory activity.

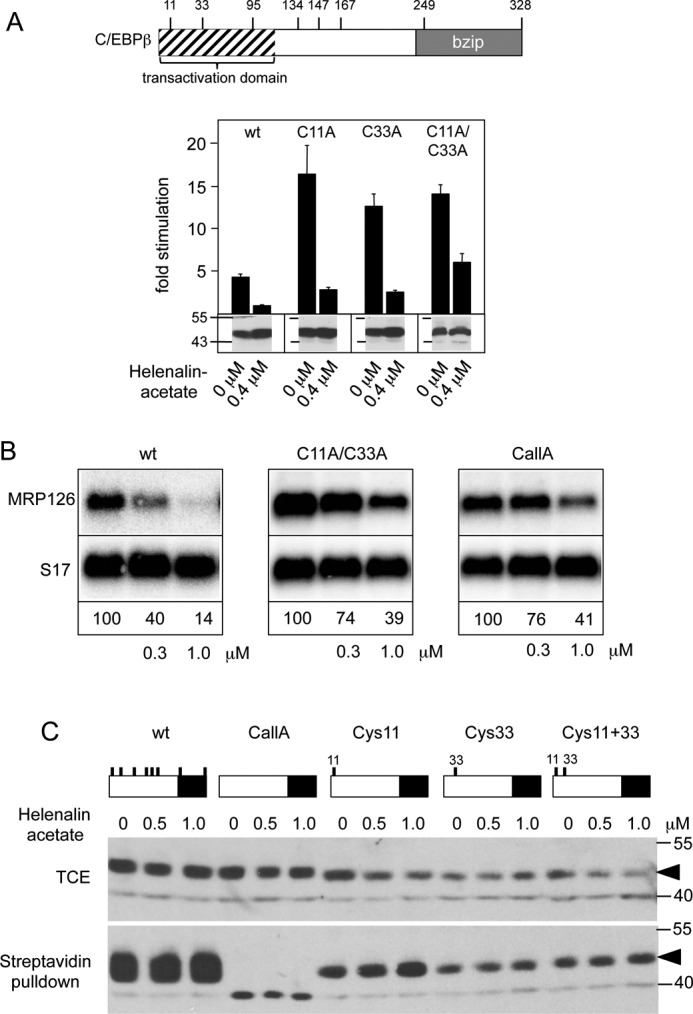

The Inhibition of C/EBPβ by Helenalin Acetate Does Not Involve Irreversible Covalent Reaction with Cysteine Residues

Our data suggested that the presence of both potentially reactive sites in the specific three-dimensional structure of helenalin acetate determines its inhibitory activity. We were therefore interested to know whether the cysteine residues of C/EBPβ, which are the likely candidates for covalent attack, are involved in the inhibitory mechanism of helenalin acetate. We have previously shown that helenalin acetate inhibits only the LAP* isoform, but not the LAP isoform, which lacks the first 21 N-terminal amino acids of C/EBPβ (26). This strongly suggested that helenalin acetate targets the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ, which contains cysteine residues at positions 11 and 33. To study the role of these residues, we mutated them individually or in combination to alanine and analyzed the sensitivity of the resulting proteins toward helenalin acetate. Surprisingly, Fig. 4A shows that the cysteine mutants have somewhat increased basal activity. We do not know the reasons for this increase; however, the cysteines in C/EBPβ have been shown to form disulfide bridges (35), whose disruption by the mutations might affect the structure of the protein. The N-terminal part of C/EBPβ has also been shown to bind to inhibitory factors (14, 36), whose binding might be weakened by the loss of the cysteine residues. In any case, Fig. 4A shows that individual mutation of either Cys-11 or Cys-33 had no effect on the sensitivity of the protein toward helenalin acetate, whereas the combination of both mutations slightly reduced its sensitivity. We confirmed this finding using the expression of the endogenous C/EBP-inducible MRP126 gene as read-out for C/EBPβ activity (Fig. 4B). Because the C11A/C33A double mutant was still inhibited by helenalin acetate, we generated a completely cysteine-free mutant of C/EBPβ (referred to as CallA) to investigate whether the other cysteines are responsible for the residual sensitivity toward helenalin acetate. However, the sensitivity of the cysteine-free C/EBPβ was not decreased more than that of the C11A/C33A double mutant (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of C/EBPβ activity by helenalin acetate is not due to the alkylation of cysteine residues of C/EBPβ. A, the positions of cysteine residues of C/EBPβ are shown schematically at the top. The panel below illustrates reporter assays with C/EBPβ mutants lacking Cys-11 or Cys-33 or both. Reporter assays were performed as in Fig. 1A. Aliquots of the cell extracts were used to visualize the amounts of C/EBPβ (bottom panels). Error bars show the S.D. B, QT6 cells were transfected with expression vectors for wild-type or C/EBPβ mutants lacking cysteines 11 and 33 (C11A/C33A) or all cysteines (CallA) and treated with the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate. Cells were harvested after 12 h and analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of MRP126 and S17 mRNAs. The numbers below the blots indicate the relative expression levels of MRP126 mRNA. C, QT6 cells were transfected with expression vectors for the different C/EBPβ mutants (containing only the indicated cysteine residues) and treated for 12 h with or without helenalin acetate, as indicated. Cell extracts were then subjected to biotinylation with BMCC-Biotin, followed by incubation with streptavidin agarose. Total cell extracts (TCE) and bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, using antibodies against C/EBPβ. Numbers on the side of the Western blots in A and C refer to molecular weight markers.

To investigate whether cysteines 11 and 33 undergo covalent modification by helenalin acetate, we generated C/EBPβ mutants containing only Cys-11 or Cys-33 or both of them. These mutants, wild-type C/EBPβ and the cysteine-free C/EBPβ, were then expressed in fibroblasts in the absence or presence of helenalin acetate. Cell extracts were then incubated with the cysteine-specific biotinylation reagent BMCC-Biotin (1-biotinamido-4-[4′-(maleimidomethyl) cyclohexanecarboxamido]butane, Thermo Scientific), followed by binding of biotinylated proteins to streptavidin beads and Western blotting. We reasoned that if helenalin acetate binds in an irreversible covalent manner to Cys-11 or -33 in vivo, these residues would no longer be available for subsequent biotinylation in vitro. Fig. 4C shows that all C/EBPβ mutants containing one or more cysteine residues were bound to streptavidin beads, whereas the cysteine-free C/EBPβ was not bound, indicating that the streptavidin pulldown was specific. Importantly, treatment with helenalin acetate did not decrease the binding to the streptavidin beads for any of the constructs, indicating that Cys-11 and -33 were not covalently modified by helenalin acetate. Together with the finding that a completely cysteine-free C/EBPβ was still inhibited by helenalin acetate, we concluded that helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ by a mechanism that does not involve covalent modification of cysteine residues.

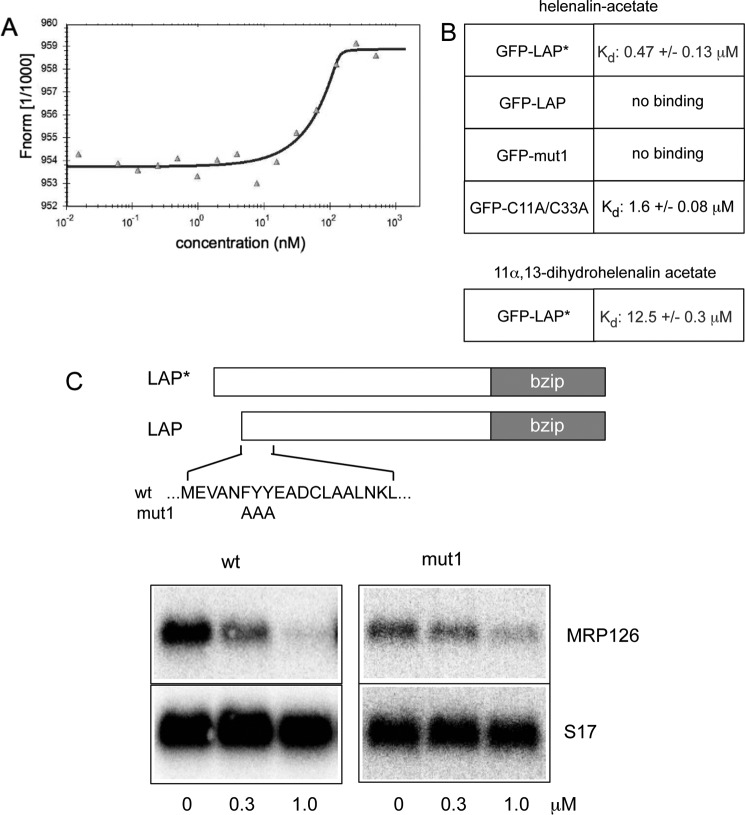

Helenalin Acetate Binds to the N-terminal Part of C/EBPβ

The finding that helenalin acetate does not inhibit C/EBPβ by alkylation of cysteine residues prompted us to explore whether helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ by direct binding. The fact that the stereoisomers helenalin and mexicanin-I differ significantly in their C/EBPβ inhibitory activity (26) underscores the idea that the three-dimensional structure of helenalin acetate is crucial for its inhibitory activity, consistent with a stereospecific binding mechanism. To examine the binding of helenalin acetate to C/EBPβ, we employed microscale thermophoresis (MST), a biophysical method to characterize molecular interactions. Thermophoresis is based on the directed movement of molecules along a temperature gradient, which is sensitive to changes of the molecule/solvent interface caused by molecular interactions and, thus, permits measurement of binding constants for biomolecular interactions, such as protein-protein or protein-small-molecule interactions (37). To detect binding of helenalin acetate to C/EBPβ by microscale thermophoresis, a constant amount of a cell extract containing GFP-LAP* was titrated with increasing amounts of helenalin acetate. Fig. 5A shows the result of a representative thermophoresis experiment as an example. Based on the quantification of replicate binding experiments, we have previously reported that helenalin acetate is able to bind to GFP-LAP* with an approximate dissociation constant of less than 1 μm, in accordance with the strong inhibition of C/EBPβ activity by helenalin acetate seen in Fig. 5C and reported before (26). Interestingly, GFP-LAP showed no binding of helenalin acetate, consistent with the finding that helenalin acetate inhibits the LAP* isoform but not the LAP isoform of C/EBPβ (26). These experiments therefore suggested that helenalin acetate binds to the N-terminal domain of LAP*. To further explore the specificity of the binding of helenalin acetate to C/EBPβ, we performed MST experiments with a mutant of C/EBPβ (C/EBPβ-mut1) that is significantly less sensitive to helenalin acetate than wt C/EBPβ. In this mutant, a highly conserved FYY amino acid motif is replaced by alanine residues. As shown in Fig. 5C, the activity of the mutant C/EBPβ was only marginally affected by helenalin acetate. MST experiments showed that the reduced sensitivity correlated with reduced binding of helenalin acetate, providing further evidence that helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ by direct binding to the N-terminal region of C/EBPβ (Fig. 5B). Presumably, the amino acid replacements cause changes of the structure of the N-terminal domain of the mutant protein that decrease the binding of helenalin acetate. We also measured the binding of helenalin acetate to the C11A/C33A mutant of C/EBPβ and found that binding occurred with reduced affinity (Fig. 5B). This provides a plausible explanation for the observation that the C11A/C33A mutant is less sensitive toward helenalin acetate than the wild-type protein (Fig. 4A). Finally, we analyzed the binding of the inactive compound 11α,13-dihydrohelenalin acetate to GFP-LAP*. Again, MST experiments showed very weak binding, consistent with the lack of inhibition of LAP* by this compound (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these experiments strongly support the notion that helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ mainly by specific binding to the N-terminal domain of the protein. We noted that the activity of C/EBPβ-mut1 was slightly inhibited at high concentrations of helenalin acetate, although no binding was detected in the MST experiment. We therefore do not exclude the possibility that inhibition of C/EBPβ at higher concentrations of helenalin acetate could be due to additional effects on other proteins, such as p300 or other proteins binding to C/EBPβ.

FIGURE 5.

Helenalin acetate binds to the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ. A, analysis of the binding of helenalin acetate to C/EBPβ by microscale thermophoresis. The result of a single MST experiment is shown. Constant amounts of extract from QT6 cells transfected with GFP-C/EBPβ were titrated with helenalin acetate from 1.4 nm to 50 μm. The normalized fluorescence (Fnorm 1/1000) was plotted against the concentration of helenalin acetate. B, summary of Kd values for binding of helenalin acetate or 11α,13-dihydrohelenalin acetate to wt C/EBPβ or the indicated C/EBPβ mutants. The Kd values ± S.D. were determined from several independent experiments. C, QT6 cells were transfected with expression vectors for wild-type or mutant C/EBPβ and treated with the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate. Cells were harvested after 12 h and analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of MRP126 and S17 mRNAs. The amino acid replacements in C/EBPβ-mut1 are indicated at the top.

The three-dimensional structure of the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ is not known so far. The exact location of the binding site for helenalin acetate within C/EBPβ is therefore a matter of speculation. As helenalin acetate does not bind to the LAP isoform, the first 21 amino acids of LAP* are required for binding. On the other hand, mutations (such as mut1) that affect the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal part of the LAP isoform also disrupt the binding. We therefore think that the binding site for helenalin acetate overlaps the N-terminal parts of the LAP* and LAP isoforms.

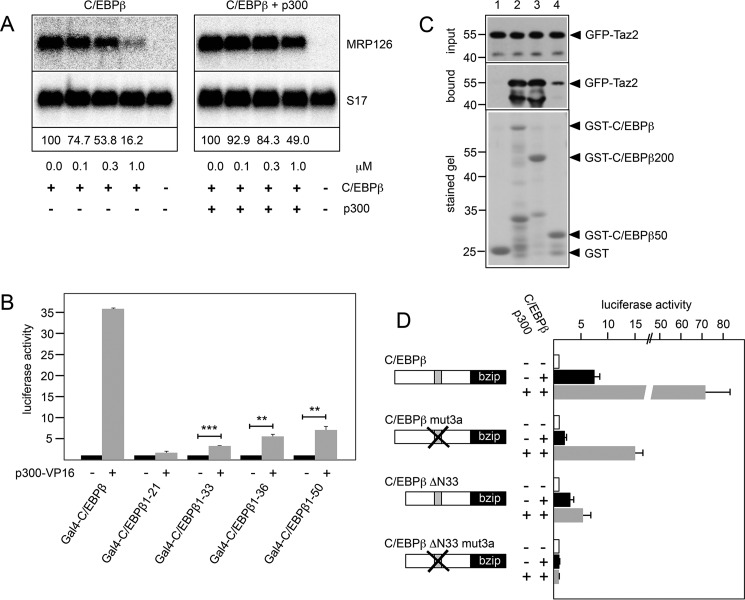

Expression of p300 Reduces the Inhibitory Effect of Helenalin Acetate

Because the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ has been implicated in interactions with several other proteins (10, 15, 38, 39), we considered the possibility that the binding of helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ activity by disturbing the cooperation of C/EBPβ with its interaction partners. The co-activator p300 has been identified as one of the key interaction and cooperation partners of C/EBPβ (38). To examine whether helenalin acetate interferes with the cooperation of C/EBPβ and p300, we first investigated whether increased expression of p300 counteracts the inhibition by helenalin acetate. Underlying this experiment is the assumption that if helenalin acetate competes with p300 for binding to C/EBPβ, overexpression of p300 might rescue C/EBPβ activity. Fig. 6A shows that transfection of an expression vector for p300 indeed partially reversed the inhibitory effect of helenalin acetate on the activity of C/EBPβ, consistent with a competition model.

FIGURE 6.

Helenalin acetate disrupts the cooperation of C/EBPβ and p300. A, QT6 cells transfected with expression vectors for C/EBPβ and p300, as indicated. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of helenalin acetate, harvested after 12 h, and analyzed by Northern blotting for expression of MRP126 and S17 mRNAs. The numbers below the blots indicate the relative expression levels of MRP126 mRNA. B, QT6 fibroblasts were transfected with the Gal4-dependent reporter gene pG5E4-38Luc, expression vectors for p300-VP16 and the indicated Gal4-C/EBPβ proteins. Cells were harvested after 12 h and analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. The columns show the average luciferase activity normalized against the β-galactosidase activity. Error bars show the S.D. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. C, in vitro pulldown experiment. Glutathione-Sepharose beads loaded with equivalent amounts of bacterially expressed GST (lane 1), GST-C/EBPβ (lane 2), GST-C/EBPβ(1–200) (lane 3), and GST-C/EBPβ(1–50) (lane 4) were incubated with identical amounts of a bacterially expressed GFP-Taz2 fusion protein. Bound GFP-Taz2 and aliquots of the input samples were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against GFP. The bottom panel shows a stained gel to confirm loading of the Sepharose beads with equivalent protein amounts. Numbers on the left side refer to molecular weight markers. D, QT6 cells were transfected with the C/EBP-dependent luciferase reporter gene p-240luc, the β-galactosidase expression vector pCMVβ, expression vectors for p300, and the indicated C/EBPβ constructs. Reporter gene activities were analyzed as in B. Error bars show the S.D.

We have previously examined the interaction of p300 with C/EBPβ in detail and showed that it is mediated by the Taz2 domain of p300 (38). In these studies, we also showed that a deletion mutant of p300 lacking the Taz2 domain does not stimulate C/EBPβ activity, demonstrating that the Taz2 domain is the relevant part of p300 that is responsible for the cooperation of p300 and C/EBPβ. According to a recent model of the interaction of the Taz2 domain with the transcription factor C/EBPϵ (40), the Taz2 domain of p300 interacts with two stretches of amino acids that are conserved among C/EBP family members and are located at positions 68–80 and 115–123 of C/EBPβ. Because C/EBPϵ lacks the LAP*-specific N-terminal sequences of C/EBPβ, it remained open in this model whether these sequences also bind to the Taz2 domain. To address whether this is the case, we performed two-hybrid experiments with VP16-p300 (encompassing the Taz2 domain) and Gal4-C/EBPβ fusion proteins containing various parts from the N terminus of C/EBPβ. Fig. 6B shows that the LAP*-specific N-terminal 21 amino acids on their own did not interact with the Taz2 domain; however, when additional sequences were included, binding to the Taz2 domain was observed. Thus, in addition to the p300 binding regions at positions 68–80 and 115–123, the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ also interacts with the Taz2 domain.

To confirm this interaction by an independent approach, we performed in vitro pulldown experiments using bacterially expressed GFP-Taz2 and several GST-C/EBPβ fusion proteins. As expected, GFP-Taz2 bound strongly to full-length C/EBPβ or a shorter construct containing only amino acids 1–200 of C/EBPβ, fused to GST, both of which contain the known interaction sites for the Taz2 domain at amino acids 68–80 and 115–123, whereas no binding was detected to GST alone (Fig. 6C, lanes 1–3). Importantly, a GST-C/EBPβ fusion protein containing only amino acids 1–50 of C/EBPβ also interacted with the Taz2 domain, although less strongly than full-length C/EBPβ, corroborating the result of the two-hybrid experiment (Fig. 6C, lane 4). Both experiments therefore demonstrate that the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ also harbors a binding site for the Taz2 domain. The fact that only bacterially expressed proteins were used in the pulldown experiment also indicates that the interaction occurs in the absence of other eukaryotic proteins and, hence, presumably is a direct protein-protein interaction.

We were therefore interested to investigate whether the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ contributes to the cooperation of C/EBPβ with p300. To address this question, we performed reporter experiments with full-length and N-terminally truncated versions of C/EBPβ carrying additional mutations in one of the conserved p300 interaction sites (referred to as mut3a). Fig. 6D shows that the mut3a version of full-length C/EBPβ was still stimulated by co-transfection of a p300 expression vector, although less strongly than the wild-type construct, whereas the mut3a version of C/EBPβ-ΔN33 was completely inactive and was not stimulated by co-expression of p300. This indicated that the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ is crucial for the cooperation with p300. Furthermore, comparison of the stimulation of the activity of the full-length and truncated wild-type forms of C/EBPβ by p300 clearly showed that the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ significantly enhances the ability to cooperate with p300. Taken together, it is evident that the N-terminal sequences of C/EBPβ significantly enhance its ability to cooperate with p300.

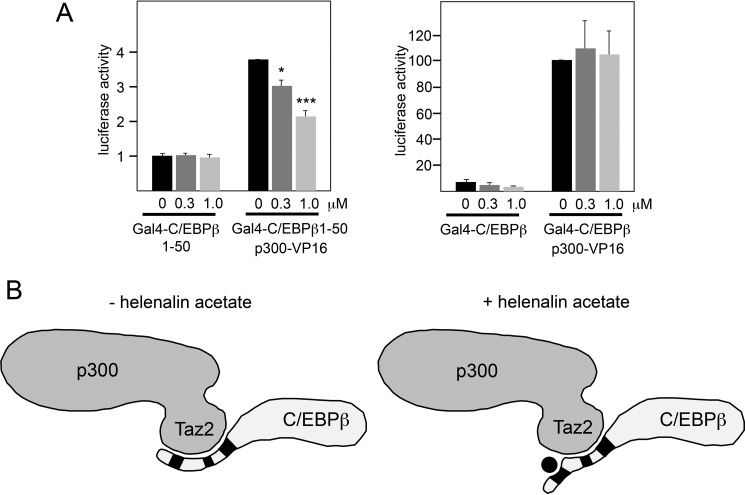

Helenalin Acetate Disrupts the Interaction between the Taz2 Domain of p300 and the N-terminal Domain of C/EBPβ

The experiments described above have revealed an interaction of the Taz2 domain with the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ that plays a critical role in the cooperation of C/EBPβ and p300. Importantly, this region of C/EBPβ does not encompass the previously known p300 binding sites at amino acid positions 68–80 and 115–123 of C/EBPβ. Hence, our experiments have revealed a novel interaction between C/EBPβ and the Taz2 domain of p300. We were therefore interested to see whether this interaction is affected by helenalin acetate. Fig. 7A shows that helenalin acetate clearly diminished the interaction of VP16-p300 with Gal4-C/EBPβ(1–50), indicating that it disrupts the interaction between the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ and p300. Interestingly, helenalin acetate did not disrupt the interaction of VP16-p300 with a fusion protein of Gal4 and full-length C/EBPβ (Fig. 7A). Presumably, the p300 binding regions in the center of C/EBPβ are sufficient for the overall interaction of C/EBPβ and p300. Taken together, our data suggest the model illustrated in Fig. 7B. In this model, the Taz2 domain interacts with three distinct regions of C/EBPβ, one of which is disrupted by helenalin acetate. As depicted in this model, helenalin acetate might affect the arrangement (and, presumably, the function) of the N-terminal sequences of C/EBPβ in the C/EBPβ-p300 complex.

FIGURE 7.

Helenalin acetate disrupts the interaction between the Taz2 domain and the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ. A, QT6 fibroblasts were transfected with expression vectors for p300-VP16 and the indicated Gal4-C/EBPβ proteins. Cells were additionally treated without or with helenalin acetate, as indicated. Cells were harvested after 12 h and analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. The columns show the average luciferase activity normalized against the β-galactosidase activity. Error bars show the S.D. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. B, model describing the influence of helenalin acetate on the C/EBPβ-p300 interaction. The Taz2 domain of p300 is highlighted. The black boxes mark the binding sites for the Taz2 domain in the N-terminal part and between amino acids 68–80 and 115–123 of C/EBPβ. Helenalin acetate is shown as a black circle. Binding of helenalin acetate to the N-terminal region of C/EBPβ displaces this region from the Taz2 domain of p300 while leaving the other interactions intact.

Discussion

By using an engineered cell line with a GFP-based Myb-inducible reporter gene as a tool to search for inhibitors of the transcription factor c-Myb, we have recently identified helenalin acetate as a highly active small-molecule inhibitor of C/EBPβ (26). Together with a variety of structurally related compounds, helenalin acetate was initially thought to be a Myb inhibitor. However, further work showed that helenalin acetate does not inhibit Myb but instead inhibits C/EBPβ. This unintentional discovery of a C/EBPβ inhibitor instead of a Myb inhibitor can be explained by the fact that the cis-elements that drive the Myb-dependent reporter gene in this cell line are derived from the myeloid-specific Myb target gene mim-1, which is activated cooperatively by Myb together with C/EBPβ or other C/EBP transcription factors (41–43). Like direct Myb inhibitors, compounds that decrease the activity of C/EBPβ will therefore also reduce the expression of the reporter gene. We have recently investigated a series of almost 70 structurally related sesquiterpene lactones with the GFP-based reporter system to establish structure-activity relationships to explain their inhibitory effects on activity of the Myb-dependent reporter gene (44). On the grounds of these considerations, it may be hypothesized that these compounds act by related mechanisms in which C/EBPβ rather than c-Myb is involved as a major target.

There is now strong evidence for pro-oncogenic roles of C/EBPβ in certain tumors, which has raised interest in C/EBPβ as a potential drug target. Because helenalin acetate is the first highly active small-molecule inhibitor of C/EBPβ, we have characterized its inhibitory activity in more detail. Helenalin acetate and helenalin are well known for their anti-inflammatory activities, which have been attributed to their ability to inhibit the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB. One important result of our work is that both compounds are actually significantly more active as inhibitors of C/EBPβ than of NF-κB. Like NF-κB, C/EBPβ also plays major roles in inflammatory processes, for example by controlling the transcription of various pro-inflammatory genes, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, NO synthase, and others (29). Furthermore, knock-out of C/EBPβ in mice leads to defects in their innate, humoral, and cellular immunity, further pointing to important functions of C/EBPβ in immune and inflammatory responses. That helenalin and helenalin acetate inhibit C/EBPβ significantly more potently than NF-κB suggests that the inhibition of C/EBPβ also contributes to the anti-inflammatory activities of helenalin and helenalin acetate.

The main aim of this study was to explore the mechanism that is responsible for the inhibition of C/EBPβ by helenalin acetate. Our initial characterization of its inhibitory activity had shown that helenalin acetate selectively inhibits the LAP* isoform of C/EBPβ. Neither the LAP isoform nor the related transcription factor C/EBPα was significantly inhibited, which has indicated that the N-terminal domain of LAP* plays a key role in the inhibitory mechanism (26). Helenalin acetate contains reactive groups that are able to form covalent adducts with cysteine residues, as reported in case of NF-κB. However, in contrast to the inhibition of NF-κB, our data suggest that helenalin acetate inhibits C/EBPβ by a non-covalent binding mechanism. Although mutation of Cys-11 and -33 in the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ renders the protein somewhat more resistant to inhibition, these cysteines are not covalently modified by helenalin acetate. Rather, the analysis of the inhibitory potential of several related compounds strongly supports the notion that the specific three-dimensional structure of helenalin acetate, and not the mere presence of reactive groups, is responsible for its inhibitory activity. Support for a non-covalent inhibitory mechanism also comes from microscale thermophoresis measurements, which have allowed us to determine a binding constant for the interaction of helenalin acetate and full-length C/EBPβ. These measurements have confirmed that only the LAP* but not the LAP isoform binds helenalin acetate, which is consistent with the fact that only LAP* is inhibited by helenalin acetate. Furthermore, these experiments have revealed that a mutation of the conserved FYY motif in the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ decreases the sensitivity toward helenalin acetate and also reduces its binding to C/EBPβ. Likewise, the C11A/C33A mutant, which is less sensitive, shows decreased binding to helenalin acetate. Thus, the reduced sensitivity due to mutation of the FYY motif and the replacement of Cys-11 and -33 by alanine most likely reflects structural alterations of the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ that reduce the affinity for helenalin acetate. Taken together, our results strongly argue that a stereospecific binding mechanism of helenalin acetate is responsible for the inhibition of C/EBPβ.

Our data indicate that the binding of helenalin acetate to C/EBPβ disturbs its cooperation with the co-activator p300. As shown before, binding of p300 to C/EBPβ is mediated by the Taz2 domain of p300 and two conserved stretches of amino acids located at positions 68–80 and 115–123 of C/EBPβ, which form a tight complex with the Taz2 domain (38, 40). We have now demonstrated by two-hybrid and by GST pulldown experiments that the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ is also involved in interactions with the Taz2 domain of p300 and, furthermore, that this part of C/EBPβ contributes significantly to the cooperation with p300 (Fig. 6, B–D). Importantly, the two-hybrid experiments have shown that helenalin acetate disrupts this interaction (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, helenalin acetate disrupts the interaction of the Taz2 domain only with the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ but not with the full-length protein. Overall, these findings suggest the model, illustrated in Fig. 7B, in which helenalin acetate binds to the N-terminal region of C/EBPβ and thereby disturbs the interaction of this part of C/EBPβ with p300 while leaving the interaction of p300 with the binding sites at positions 68–80 and 115–123 of C/EBPβ intact. This suggests that helenalin acetate influences how the N-terminal sequences of C/EBPβ are arranged in the C/EBPβ-p300 complex. How this leads to the inhibition of C/EBPβ activity is presently not known. It is possible that the altered conformation of the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ in the C/EBPβ-p300 complex affects other protein-protein interactions or leads to a different pattern of covalent modifications in the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ. For example, the acetylation of a specific lysine residue in the N-terminal part of C/EBPβ by p300, Lys-39, is known to exert a major effect on the activity of C/EBPβ (45). Moreover, the N-terminal domain of C/EBPβ has been implicated in the binding of other proteins, including the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (39), the Mediator complex (15), and protein kinase Hipk2 (10). It is therefore possible that the inhibitory mechanism of helenalin acetate is even more complex and also involves inhibition of further protein-protein interactions or post-translational modifications of the N-terminal domain of LAP*.

As mentioned above, we have recently used the GFP-based Myb-inducible reporter system to perform a structure-activity study of the inhibitory activities of a variety of almost 70 sesquiterpene lactones, including helenalin acetate as one of the strongest inhibitors (44). Based on the inhibition of c-Myb-dependent reporter gene activity by this set of related compounds, a thorough analysis of the influence of molecular structure on inhibitory potency was carried out. A rather straightforward correlation was observed between the compounds' inhibitory activity and their potential ability to act as Michael acceptors (i.e. the number of structural elements in the molecule that are potentially able to undergo covalent reactions with nucleophilic partial structures of proteins). Interestingly, the potential reactivity alone did not fully explain the level of activity, but it was found that the steric orientation of the reactive centers played an important role. The resulting quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) model, giving a statistically sound, reasonable, and plausible explanation for the differences in activity between the various compounds, is in partial agreement with the observation of the present study that the mere presence of reactive structure elements does not suffice to explain high activity. However, the present study clearly shows that helenalin acetate does not bind in an irreversible covalent manner to C/EBPβ, and this finding, at first sight, appears contradictory to the structure-activity relationship requiring the presence of more than one reactive partial structure as a prerequisite for high activity. However, it may simply indicate that, as stated above, apart from a non-covalent binding mechanism to C/EBPβ, there may be further effects related to covalent binding to other proteins involved in the overall observed activity that remain yet to be elucidated. From the fact that a statistically relevant common structure-activity relationship exists for all investigated sesquiterpene lactones, it may be deduced that they all share a common mechanism of action. Experiments investigating a broader structural variety of sesquiterpene lactones for their binding to and inhibition of C/EBPβ may provide important evidence for the elucidation of the full mechanism of inhibition of the transcriptional machinery under study and will also shed further light on the molecular reasons for their anti-inflammatory and anti-tumoral activity. Studies in this direction are therefore under way.

Overall, our work has identified helenalin acetate as the first highly potent small-molecule inhibitor of C/EBPβ. We envision helenalin acetate as a useful tool to explore the role of C/EBPβ in normal and in tumor cells. Because it acts primarily on the LAP* isoform of C/EBPβ, helenalin acetate will also be useful to dissect the functions of the LAP* and LAP isoforms.

Experimental Procedures

Cells

QT6 is a line of quail fibroblasts, and 3T3-L1 is a mouse pre-adipocyte line whose differentiation into fat cells was induced by published procedures (31). All cell lines were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Sesquiterpene Lactones

Helenalin, helenalin acetate, helenalin isobutyrate, helenalin methylbutyrates, 11α,13-dihydrohelenalin acetate, and chamissonolide were isolated from Arnica species (44). 2-Cyclopentene-1-one and α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The purity of all compounds was >90% by HPLC and/or 1H NMR. 10 mm stock solutions were prepared in DMSO. Human recombinant TNFα was obtained from Biomol.

Transfections

QT6 fibroblasts were transfected by calcium phosphate co-precipitation, and reporter gene activities were analyzed as described (46). The C/EBP-inducible luciferase reporter gene p-240Luc and the Gal4-dependent reporter gene pG5E4-38Luc have been described before (38, 47). The NF-κB luciferase reporter gene pGL2-6×NFκB-luc was obtained from C. Scheidereit. The β-galactosidase reporter gene pCMVβ was from Clontech (Heidelberg, Germany). All reporter studies were done in at least 3 independent experiments, with duplicate measurements in each experiment. Expression vectors for chicken and human C/EBPβ have been described (48, 49). The expression vector for human C/EBPβ was kindly provided by G. Steger. Point mutants of chicken C/EBPβ carrying replacements of individual or all cysteine residues by alanine or the FYY motif (mut1) were generated by PCR using appropriate primers. pEYFP-N1-C/EBPβ wild type, C11A/C33A, or mut1 and pEYFP-N1-C/EBPβ-ΔN21 were generated by cloning the full-length or N-terminally truncated coding region of chicken C/EBPβ between the EcoRI and BamHI sites into pEYFP-N1. The C/EBPβ stop codon was removed and replaced by a BamHI site. pVP16/p300 and a full-length Gal4-C/EBPβ construct have been described (48). Gal4-C/EBPβ (1–21), (1–33), (1–36), and (1–50) were generated by PCR amplification of the indicated parts of the chicken C/EBPβ coding region and cloning them downstream of the Gal4 coding region. Similarly, the GST-C/EBPβ(1–50) was generated by cloning the PCR-amplified coding region for amino acids 1–50 of chicken C/EBPβ into pGex-6P2. C/EBPβ-mut3a, C/EBPβ-ΔN33, and C/EBPβ-ΔN33-mut3a have been described (48). C/EBPβ-mut3a carries amino acid substitutions in one of the conserved p300 interaction sites, changing the amino acid sequence at positions 101–107 (of chicken C/EBPβ) from DLFSDFL to AAASAAA. The expression vector for full-length human p300 was obtained from R. Eckner. The bacterial expression vector for a GFP-Taz2 fusion protein was generated by subcloning the PCR-amplified p300 coding sequences for amino acids 1710–1891 between the BamHI and NotI of the bacterial expression vector pGV82 (gift from H. Mootz, Institute for Biochemistry, University of Münster). Human recombinant TNFα was obtained from Biomol. The expression of the endogenous MRP126 and ribosomal protein S17 mRNAs was analyzed as described before (10).

Microscale Thermophoresis

To measure the dissociation constant for the interaction of helenalin acetate with C/EBPβ, extracts of QT6 cells transfected with YFP-C/EBPβ or YFP-C/EBPβ-ΔN21 were prepared in 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 120 mm sodium chloride, 1 mm EDTA, 6 mm EGTA, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Concentrations of helenalin acetate ranging from 1.4 nm to 50 μm were combined with constant amounts of cell extract, incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature, and filled in capillaries to perform thermophoresis measurements in a NanoTemper Monolith (NT.015) instrument. Thermophoresis was performed at 1475 nm ± 15 nm. Data from several independent experiments were normalized to ΔFnorm [‰] (10 × (Fnorm(bound) − Fnorm(unbound)) or fraction bound (ΔFnorm [‰]/amplitude) to calculate the Kd value.

Biotinylation of Cell Extracts

Transfected cells were lysed in ELB buffer (120 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mm NaF, 1 mm EDTA, 6 mm EGTA, 15 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm PMSF, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 ng/ml aprotinin, 0.2 ng/ml leupeptin, 1 ng/ml pepstatin). After removal of input samples, 450 μl of the cell extract were mixed with 50 μl of 8 μm EZ-LinkTM BMCC-Biotin (Thermo Scientific) dissolved in DMSO. The solution was first kept on ice for 4 h and then incubated with Streptavidin-agarose beads overnight with constant agitation. After washing the beads with ELB buffer, bound protein and input samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

In Vitro GST Pulldown

Purification of GST fusion proteins and in vitro GST pulldown experiments were performed as described before (10).

Western Blotting

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were performed by standard procedures using antibodies against chicken (43) or mouse (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H-7) C/EBPβ. Antibodies against β-actin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (AC-15). Samples of extracts from transfected cells (Figs. 1A, 3A, and 4A) were normalized to the corresponding transfection efficiency. Protein samples from untransfected cells (Fig. 2C) were loaded as equal aliquots.

Author Contributions

A. J. and K.-H. K. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. S. S. and S. M. H. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. T. J. S. designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Berkenfeld and P. Pieloch for technical assistance and H. Mootz and C. Scheidereit for plasmids.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe. This work was also supported by a fellowship from the Graduate School of Chemistry at the University of Münster (GSC-MS) (to S. M. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- C/EBPβ

- CCAAT box/enhancer-binding protein β

- MST

- microscale thermophoresis

- BMCC-Biotin

- 1-biotinamido-4-[4′-(maleimidomethyl) cyclohexanecarboxamido]butane

- p

- phosphorylated

- LAP

- liver-enriched activating protein

- LIP

- liver-enriched inhibitory protein.

References

- 1. Ramji D. P., and Foka P. (2002) CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 365, 561–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nerlov C. (2007) The C/EBP family of transcription factors: a paradigm for interaction between gene expression and proliferation control. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Descombes P., and Schibler U. (1991) A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell 67, 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ossipow V., Descombes P., and Schibler U. (1993) CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein mRNA is translated into multiple proteins with different transcription activation potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8219–8223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calkhoven C. F., Müller C., and Leutz A. (2000) Translational control of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ isoform expression. Genes Dev. 14, 1920–1932 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomis R. R., Alarcón C., Nadal C., Van Poznak C., and Massagué J. (2006) C/EBPβ at the core of the TGFβ cytostatic response and its evasion in metastatic breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell 10, 203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wethmar K., Smink J. J., and Leutz A. (2010) Upstream open reading frames: molecular switches in (patho)physiology. Bioessays 32, 885–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buck M., Poli V., van der Geer P., Chojkier M., and Hunter T. (1999) Phosphorylation of rat serine 105 or mouse threonine 217 in C/EBPβ is required for hepatocyte proliferation induced by TGFα. Mol. Cell 4, 1087–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kowenz-Leutz E., Twamley G., Ansieau S., and Leutz A. (1994) Novel mechanism of C/EBPβ (NF-M) transcriptional control: activation through derepression. Genes. Dev. 8, 2781–2791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steinmann S., Coulibaly A., Ohnheiser J., Jakobs A., and Klempnauer K.-H. (2013) Interaction and cooperation of the CCAAT-box enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ) with the homeo-domain interacting protein kinase 2 (Hipk2). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 22257–22269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ceseña T. I., Cardinaux J. R., Kwok R., and Schwartz J. (2007) CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) β is acetylated at multiple lysines: acetylation of C/EBPβ at lysine 39 modulates its ability to activate transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 956–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joo M., Park G. Y., Wright J. G., Blackwell T. S., Atchison M. L., and Christman J. W. (2004) Transcriptional regulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene in macrophages by PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6658–6665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu M., Nie L., Kim S. H., and Sun X. H. (2003) STAT5-induced Id-1 transcription involves recruitment of HDAC1 and deacetylation of C/EBPβ. EMBO J. 22, 893–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pless O., Kowenz-Leutz E., Knoblich M., Lausen J., Beyermann M., Walsh M. J., and Leutz A. (2008) G9a-mediated lysine methylation alters the function of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26357–26363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kowenz-Leutz E., Pless O., Dittmar G., Knoblich M., and Leutz A. (2010) Crosstalk between C/EBPβ phosphorylation, arginine methylation, and SWI/SNF/Mediator implies an indexing transcription factor code. EMBO J. 29, 1105–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eaton E. M., and Sealy L. (2003) Modification of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β by the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) family members, SUMO-2 and SUMO-3. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33416–33421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rask K., Thörn M., Pontén F., Kraaz W., Sundfeldt K., Hedin L., and Enerbäck S. (2000) Increased expression of the transcription factors CCAAT-enhancer binding protein-β (C/EBPβ) and C/EBPζ (CHOP) correlate with invasiveness of human colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 86, 337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sebastian T., and Johnson P. F. (2006) Stop and go: anti-proliferative and mitogenic functions of the transcription factor C/EBPβ. Cell Cycle 5, 953–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim M. H., Minton A. Z., and Agrawal V. (2009) C/EBPβ regulates metastatic gene expression and confers TNF-α resistance to prostate cancer cells. Prostate 69, 1435–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Homma J., Yamanaka R., Yajima N., Tsuchiya N., Genkai N., Sano M., and Tanaka R. (2006) Increased expression of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β correlates with prognosis in glioma patients. Oncol. Rep. 15, 595–601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aguilar-Morante D., Cortes-Canteli M., Sanz-Sancristobal M., Santos A., and Perez-Castillo A. (2011) Decreased CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β expression inhibits the growth of glioblastoma cells. Neuroscience 176, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aguilar-Morante D., Morales-Garcia J. A., Santos A., and Perez-Castillo A. (2015) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β induces motility and invasion of glioblastome cells through transcriptional regulation of the calcium binding protein S100A4. Oncotarget 6, 4369–4384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carro M. S., Lim W. K., Alvarez M. J., Bollo R. J., Zhao X., Snyder E. Y., Sulman E. P., Anne S. L., Doetsch F., Colman H., Lasorella A., Aldape K., Califano A., and Iavarone A. (2010) The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature 463, 318–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Piva R., Pellegrino E., Mattioli M., Agnelli L., Lombardi L., Boccalatte F., Costa G., Ruggeri B. A., Cheng M., Chiarle R., Palestro G., Neri A., and Inghirami G. (2006) Functional validation of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase signature identifies CEBPB and BCL2A1 as critical target genes. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3171–3182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anastasov N., Bonzheim I., Rudelius M., Klier M., Dau T., Angermeier D., Duyster J., Pittaluga S., Fend F., Raffeld M., and Quintanilla-Martinez L. (2010) C/EBPβ expression in ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma is required for cell proliferation and is induced by the STAT3 signaling pathway. Haematologica 95, 760–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jakobs A., Uttarkar S., Schomburg C., Steinmann S., Coulibaly A., Schlenke P., Berdel W. E., Müller-Tidow C., Schmidt T. J., and Klempnauer K.-H. (2016) An isoform-specific C/EBPβ inhibitor targets acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia 30, 1612–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lyß G., Knorre A., Schmidt T. J., Pahl H. L., and Merfort I. (1998) The anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene lactone helenalin inhibits the transcription factor NF-κB by directly targeting p65. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33508–33516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. García-Piñeres A. J., Castro V., Mora G., Schmidt T. J., Strunck E., Pahl H. L., and Merfort I. (2001) Cysteine 38 in p65/NF-κB plays a crucial role in DNA binding inhibition by sesquiterpene lactones. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39713–39720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huber R., Pietsch D., Panterodt T., and Brand K. (2012) Regulation of C/EBPβ and resulting functions in cells of the monocytic lineage. Cell. Signal. 24, 1287–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Büchele B., Zugmaier W., Lunov O., Syrovets T., Merfort I., and Simmet T. (2010) Surface plasmon resonance analysis of nuclear factor-κB protein interactions with the sesquiterpene lactone helenalin. Anal. Biochem. 401, 30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lane M. D., Tang Q. Q., and Jiang M. S. (1999) Role of the CCAAT enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs) in adipocyte differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266, 677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Otto T. C., and Lane M. D. (2005) Adipose development: from stem cell to adipocyte. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmidt T. J. (1997) Helenanolide type sesquiterpene lactones. III. Rates and stereochemistry in the reaction of helenalin and related helenanolides with sulfhydryl containing biomolecules. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 5, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmidt T. J., Lyss G., Pahl H. L., and Merfort I. (1999) Helenanolide type sesquiterpene lactones. Part 5. The role of glutathione addition under physiological conditions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7, 2849–2855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Su W.-C., Chou H.-Y., Chang C.-J., Lee Y.-M., Chen W.-H., Huang K.-H., Lee M.-Y., and Lee S.-C. (2003) Differential activation of a C/EBPβ isoform by a novel redox switch may confer the lipopolysaccharide-inducible expression of interleukin-6 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51150–51158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steinmann S., Schulte K., Beck K., Chachra S., Bujnicki T., and Klempnauer K.-H. (2009) v-Myc inhibits C/EBPβ activity by preventing C/EBPβ-induced phosphorylation of the co-activator p300. Oncogene 28, 2446–2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jerabek-Willemsen M., Wienken C. J., Braun D., Baaske P., and Duhr S. (2011) Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 9, 342–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mink S., Haenig B., and Klempnauer K.-H. (1997) Interaction and functional collaboration of p300 and C/EBPβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6609–6617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kowenz-Leutz E., and Leutz A. (1999) A C/EBPβ isoform recruits the SWI/SNF complex to activate myeloid genes. Mol. Cell 4, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhaumik P., Davis J., Tropea J. E., Cherry S., Johnson P. F., and Miller M. (2014) Structural insights into interactions of C/EBP transcriptional activators with the Taz2 domain of p300. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 1914–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burk O., Mink S., Ringwald M., and Klempnauer K.-H. (1993) Synergistic activation of the chicken mim-1 gene by v-myb and C/EBP transcription factors. EMBO J. 12, 2027–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ness S. A., Kowenz-Leutz E., Casini T., Graf T., and Leutz A. (1993) Myb and NF-M: combinatorial activators of myeloid genes in heterologous cell types. Genes Dev. 7, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mink S., Kerber U., and Klempnauer K.-H. (1996) Interaction of C/EBPβ and v-Myb is required for synergistic activation of the mim-1 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1316–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schomburg C., Schuehly W., Da Costa F. B., Klempnauer K.-H., and Schmidt T. J. (2013) Natural sesquiterpene lactones as inhibitors of Myb-dependent gene expression: structure-activity relationships. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 63, 313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ceseña T. I., Cui T. X., Subramanian L., Fulton C. T., Iñiguez-Lluhí J. A., Kwok R. P., and Schwartz J. (2008) Acetylation and deacetylation regulate CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β at K39 in mediating gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 289, 94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chayka O., Kintscher J., Braas D., and Klempnauer K.-H. (2005) v-Myb mediates cooperation of a cell-specific enhancer with the mim-1 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 499–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ness S. A., Marknell A., and Graf T. (1989) The v-myb oncogene product binds to and activates the promyelocyte-specific mim-1 gene. Cell 59, 1115–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwartz C., Beck K., Mink S., Schmolke M., Budde B., Wenning D., and Klempnauer K.-H. (2003) Recruitment of p300 by C/EBPβ triggers phosphorylation of p300 and modulates coactivator activity. EMBO J. 22, 882–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hadaschik D., Hinterkeuser K., Oldak M., Pfister H. J., and Smola-Hess S. (2003) The papillomavirus E2 protein binds to and synergizes with C/EBP factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. J. Virol. 77, 5253–5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]