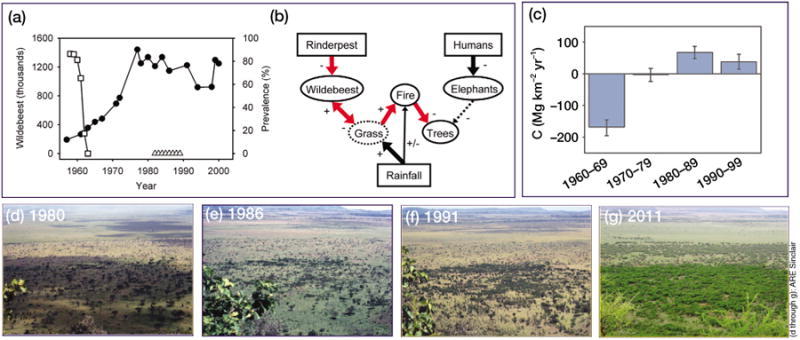

Figure 1.

African wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) were decimated by rinderpest in an 1889 outbreak and remained at low abundance for decades. When rinderpest eradication efforts were initiated in the 1960s, wildebeest abundance increased dramatically (a). Because wildebeest grazing reduces biomass of flammable grasses, thereby reducing fire frequency and increasing woody plant abundance, the return of wildebeest increased the abundance of trees (b), increasing savanna carbon sequestration (c). These changes have been very evident in the Serengeti ([d] through [g]). In (a), circles indicate wildebeest population size, whereas squares and triangles indicate prevalence of rinderpest before and after eradication, respectively. In (b), solid and dashed lines indicate direct and indirect effects, respectively; the plus and minus signs indicate direction of effects. In (c), columns show means with 95% confidence intervals (error bars). Panels (a) through (c) were adapted from Dobson et al. (2011), adapted from Holdo et al. (2009).