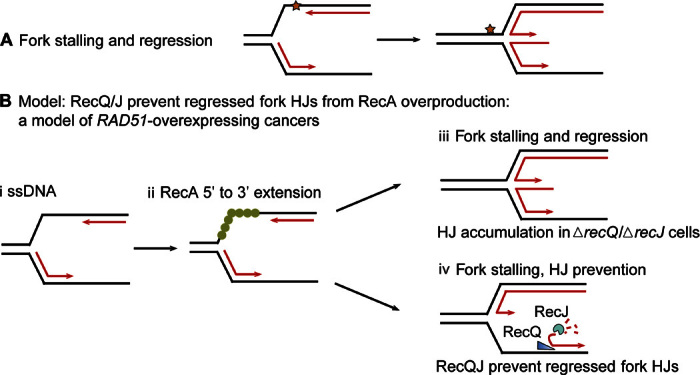

Fig. 6. Model: Promotion of regressed replication forks by overproduced RecA and prevention of their associated HJs by RecQ and RecJ.

(A) Diagram of replication fork stalling at a replication-blocking DNA lesion (star) and regression to form a HJ. When forks stall, the potential energy of DNA supercoiling ahead of the fork drives the fork backward spontaneously (94), independently of RecA biochemically (94) and in cells (33). Lines, strands of DNA; parallel lines, base-paired strands; arrowheads, 3′ ends. (B) Model for fork regression caused by excess RecA and its prevention by RecQ/RecJ. We suggest that with RecA overproduction, forks regress spuriously, without a replication-blocking DNA lesion, because of RecA polymerization on ssDNA at the fork (i and ii) instigating strand exchange with the nascent sister duplex. (ii) RecA can be loaded on ssDNA at a fork and extended 3′ from the fork junction to the ssDNA-dsDNA (double-stranded DNA) junction at the 3′ leading strand end, a RecF-independent (35) [and RecB-independent (33)] independent substrate and reaction to promote (iii) fork regression. We suggest that after RecA loading onto the ssDNA, there can be two outcomes, which are influenced by the presence of RecQ or RecJ. (iii) In the absence of RecQ or RecJ, RF HJs will accumulate. (iv) In the presence of RecQ and RecJ, RecQ unwinding of the lagging strand at the fork (19, 69) and RecJ 5′-ssDNA–dependent exonuclease can prevent some RF HJs by making a ssDNA-end fork regression structure/substrate. This 3′-ssDNA end (arrowhead) would not be bound by RDG and may be degraded by ssDNA exonucleases, preventing HJs.