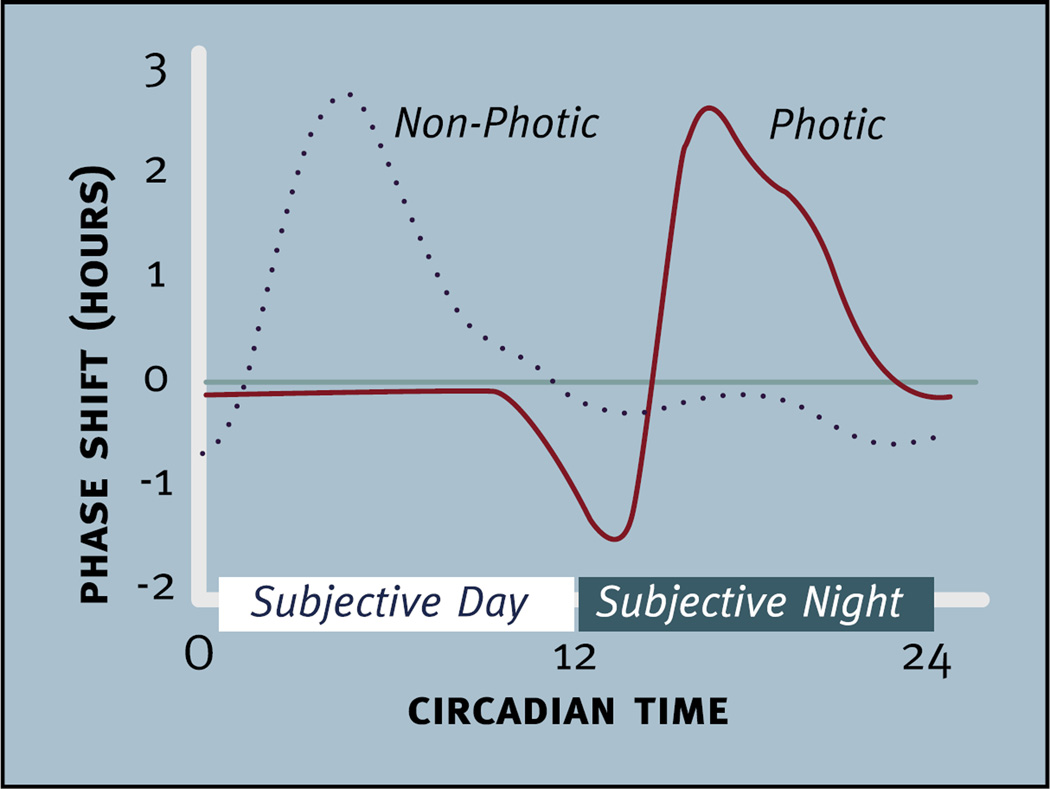

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the phase shifting effects of “photic” (solid red line) and “non-photic” stimuli (dotted black line) presented to nocturnally active rodents housed in constant darkness. Light does not produce phase shifts until the late subjective day and early subjective night when it produces phase delays. Later in the subjective night light produces phase advances. Non-photic stimuli, such as injection of neuropeptide Y into the suprachiasmatic region, induce large phase advances during the subjective day and smaller phase delays in the subjective night. Note: not all “non-photic” phase shifting stimuli produce a pattern of phase shifts like those seen in this figure. In nocturnal rodents the subjective day refers to the inactive phase and the subjective night refers to the active phase of the circadian cycle. Circadian time 12 is designated as the time of locomotor onset (modified from Webb et al., 2014).