Abstract

Introduction

Somatostatin analogues and rapamycin inhibitors are two classes of drugs available for the management of polycystic liver disease but their overall impact is not clearly established. This article systematically reviews the literature on the medical management of polycystic liver disease. The outcomes assessed include reduction in liver volume and the impact on quality of life.

Methods

The English language literature published between 1966 and August 2014 was reviewed from a MEDLINE®, PubMed, Embase™ and Cochrane Library search. Search terms included ‘polycystic’, ‘liver’, ‘sirolimus’, ‘everolimus’, ‘PCLD’, ‘somatostatin’, ‘octreotide’, ‘lanreotide’ and ‘rapamycin’. Both randomised trials and controlled studies were included. References of the articles retrieved were also searched to identify any further eligible publications. The studies included were appraised using the Jadad score.

Results

Seven studies were included in the final review. Five studies, of which three were randomised trials, investigated the role of somatostatin analogues and the results showed a mean reduction in liver volume ranging from 2.9% at six months to 4.95 ±6.77% at one year. Only one randomised study examined the influence of rapamycin inhibitors. This trial compared dual therapy with everolimus and octreotide versus octreotide monotherapy. Liver volume reduced by 3.5% and 3.8% in the control and intervention groups respectively but no statistical difference was found between the two groups (p=0.73). Two randomised trials investigating somatostatin analogues assessed quality of life using SF-36®. Only one subdomain score improved in one of the trials while two subdomain scores improved in the other with somatostatin analogue therapy.

Conclusions

Somatostatin analogues significantly reduce liver volumes after six months of therapy but have only a modest improvement on quality of life. Rapamycin inhibitors do not confer any additional advantage.

Keywords: Polycystic, Liver, Disease, Management, Sirolimus, Everolimus, Somatostatin, Octreotide, Rapamycin

Polycystic liver disease (PCLD) is an inherited condition, defined by the presence of 20 or more cysts in the liver parenchyma.1 It may occur in isolation or as part of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), where concomitant liver cysts are present in up to 80% of cases.2 The condition is progressive and overall liver volume may increase up to 3.7% annually, resulting in debilitating symptoms.3

The pathogenesis of PCLD involves multiple cysts developing in the liver parenchyma because of excessive proliferation of cholangiocytes as a result of alterations in calcium homeostasis and cyclic adenosine monophosphate activity, which stimulates protein kinase mediated proliferation.4 Cyst growth is further augmented by activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR).5 Female sex, exogenous oestrogens and multiple pregnancies are risk factors for cyst progression.1,6 and a review published in 2013 of data from three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) revealed that the rate of liver growth is highest among women under 48 years of age.7

Patients with PCLD develop symptoms owing to pressure on adjacent structures. These include abdominal discomfort, distension, early satiety and vomiting with associated malnutrition.8 The symptoms are reported to be more common in women.9 In addition, there is a significant impact on quality of life (QoL).10 In a small percentage of patients, liver cysts can result in acute complications such as cyst rupture, haemorrhage, infection or compression of vital structures (eg inferior vena cava, portal vein or biliary tract).9,11 Despite the increase in size of polycystic livers, hepatocyte function remains preserved and serum transaminases remain normal or near normal. Common laboratory findings include elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase in up to 51% and alkaline phosphatase in up to 10% of patients.9 Other findings include elevated tumour markers such as CA19–9, which is produced by the epithelial lining of the cyst wall.12

Treatment strategies for PCLD are directed at reducing the liver volume and can be broadly divided into medical and interventional approaches. Surgical and interventional strategies include aspiration and sclerotherapy, de-roofing of cysts and liver resection. Embolisation of the hepatic artery has also been used to reduce liver volumes although experience seems to be limited.13,14 Liver transplantation is reserved for patients with disabling symptoms and results in a five-year survival rate of up to 80%.15 The surgical management of PCLD has been reviewed elsewhere16 and the purpose of this paper is to systematically review the medical management of PCLD. Commonly used agents include somatostatin analogues such as octreotide and lanreotide as well as another class of drugs called mTOR inhibitors, which include sirolimus and everolimus.

Methods

Studies investigating any form of medical management of PCLD published between January 1966 and August 2014 were identified from a MEDLINE®, PubMed, Embase™ and Cochrane Library search. Search terms included ‘polycystic’, ‘liver’, ‘sirolimus’, ‘everolimus’, ‘PCLD’, ‘somatostatin’, ‘octreotide’, ‘lanreotide’ and ‘rapamycin’. References of the articles retrieved were searched to identify further publications. The quality of studies was judged according to their Jadad score.17

Any publications in the English language on medical therapy for PCLD were eligible for inclusion in the review. Studies including patients with ADPKD as well as those with isolated PCLD were included. Owing to the paucity of studies, both RCTs and case series were included. All abstracts were reviewed by the primary author (SK) and studies that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Results

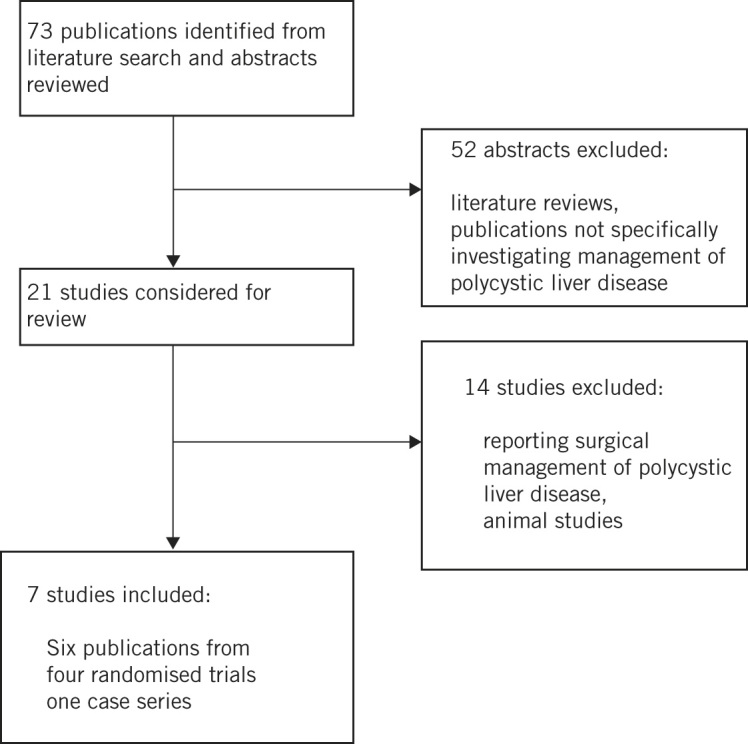

The literature search revealed 73 potential publications and their abstracts were reviewed. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of these studies. Fifty-two studies were excluded because they did not specifically examine the management of PCLD. The full text for 21 papers was obtained. Fourteen were subsequently excluded because they did not relate to the medical management of PCLD. As a result, seven studies were included in the final review (Table 1).3,18–23 Five of these (three RCTs3,18,19 and two further subsequent publications)20,21 investigated the role somatostatin analogues (Table 2). The remaining two studies (one RCT22 and one case series)23 investigated the role of mTOR inhibitors (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Quality of the studies included according to Jadad scale

| Author | Type of study | Number of patients | Random sequence generation | Conceal-ment of allocation | Blinding | Jadad score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-vention | Control | ||||||

| Van Keimpema et al18 | RCT | 27 | 27 | Adequate | Adequate | Double blinded | 5/5 |

| Caroli A. et al19 | RCT | 12* | 12* | Adequate | Adequate | Double blinded | 5/5 |

| Hogan et al3 | RCT (2:1) | 28 | 14 | Not described | Not described | Double blinded | 3/5 |

| Chrispijn M. et al21 | Case series | 41 | 0 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 0/5 |

| Hogan et al20 | Case series | 41 | 0 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 1/5 |

| Chrispijn M. et al22 | RCT | 21 | 23 | Adequate | Adequate | Double blinded | 5/5 |

| Qian Q. et al23 | Case series | 7 | 9 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 0/5 |

*Cross over study, 6 patients in intervention and control groups crossed-over after 6 months, RCT: randomised controlled trial

Table 2.

Outcomes of studies investigating the role of somatostatin analogues

| Study | Intervention | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | Method of assessment | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 1 year | 2 year | |||||

| Van Keimpema et al18 | Lanreotide | Liver volume | Kidney volume, QoL | CT volumetry | Mean reduction of 2.9% (p<0.01) in liver volume.Some improvement in QoL | ||

| Caroli A. et al19 | Octreotide | Kidney volume | Liver volume | CT volumetry | Liver volumes reduced from 1595+/- 478 ml to 1524+/- 453 ml (p<0.005) | ||

| Hogan et al3 | Octreotide | Liver volume | Kidney volume, QoL | MRI | Mean reduction of 4.95+/-6.77 % (p=0.048) in liver volume.Some improvement in QoL | ||

| Chrispijn M. et al21 | Lanreotide | Liver volume | Kidney volume, QoL | CT volumetry | Liver volume decreased by 4% (IQR 8% to 1%) after 12 months of treatment | ||

| Hogan et al20 | Octreotide | Liver volume | Kidney volume, QoL | MRI | 0.77+/-6.82 % further reduction from first year (p=0.57) | ||

QoL: quality of life, MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging, CT: computerised tomography

Table 3.

Outcomes of studies investigating the role of mTOR inhibitors

| Study | Intervention | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | Method of assessment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 18 months | |||||

| Chrispijn M. et al22 | Everolimus | Liver volume | QoL | CT volumetry | Volume reduced by 3.5% and 3.8% in the control group and intervention groups.No significant difference between the two groups (p=0.73). | |

| Qian Q. et al23 | Sirolimus | Liver volume | Kidney volume | CT volumetry | Mean reduction of 11.3+/-0.03 % (p=0.048) in liver volume in sirolimus group | |

The RCTs investigating the role of somatostatin analogues were small but well designed. The Jadad score ranged from 3/5 to 5/5. The trial by Hogan et al reported results at one year3 and then produced a second publication of long-term results at two years, in which all participants of the original trial were included in the intervention group.20 Similarly, the trial by Caroli et al reported results at six months19 and then at one year but the long-term results were not randomised.21

Only one RCT examined the influence of mTOR inhibitors.22 This trial randomised 44 patients to either 48 weeks of everolimus daily combined with octreotide every 4 weeks or to octreotide monotherapy.

Efficacy of somatostatin analogues and mTOR inhibitors

All three trials of somatostatin analogues consistently showed outcomes to be in favour of their use. The mean reduction in liver volume was 2.9% at six months in the lanreotide group in the trial by Van Keimpema et al18 Similarly, there was a reduction in volume from 1,595 ±478ml at baseline to 1,524 ±453ml at six months (p<0.005)19 and a reduction in liver volume of 4.95 ±6.77% at one year in the other RCTs.3 Both these latter trials used octreotide in the intervention group.

Two of the trials subsequently published their long-term results. The trial by Hogan et al which had shown a 4.95 ±6.77% reduction in liver volume at one year,3 crossed over all patients to receive octreotide for two years.20 There was a further reduction in liver volumes of 0.77 ±6.82% but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.57). However, it is clear that the reduced volumes were maintained with continuous octreotide usage.

Similarly, the trial by Van Keimpema et al, which revealed a 2.9% reduction in liver volume at 6 months,18 crossed over its original placebo group to receive 12 months of lanreotide and the original intervention group received a further 6 months of treatment.21 There was a median reduction in liver volume of 4% at the end of one year of lanreotide treatment although this occurred during the first six months of treatment. Patients had a repeat measurement of liver volume six months after stopping treatment and, interestingly, liver volumes were found to have recovered by 4% (interquartile range: 0–6%, p<0.05).

Only one RCT examined the influence of mTOR inhibitors.22 It randomised 44 patients either to dual therapy of everolimus and octreotide or to monotherapy with octreotide. Liver volume reduced by 3.5% and 3.8% in the control and intervention groups respectively. Although these reductions were statistically significant (both p<0.01), no significant difference was found between the two groups (p=0.73).

The other paper investigating mTOR inhibitors was a report of a single case series.23 The authors found a mean reduction of 11.85 ±0.03% in liver volume in 7 ADPKD patients who received sirolimus for a mean duration of 19 months after a renal transplant while the 9 patients who received tacrolimus showed an increase (14.13 ±0.09%) (p=0.009).

Impact on quality of life

Two of the three RCTs investigating somatostatin analogues assessed the impact on QoL. The trials by Van Keimpema et al18 and Hogan et al3 used the generic but validated SF-36® QoL questionnaire. Van Keimpema et al found that only a single subdomain score of the SF-36®, namely current health perception, improved in the lanreotide group (42 vs 62, p<0.01) whereas the values for the placebo group remained stable (43 vs 41, p>0.05).18 Similarly, in the trial by Hogan et al, two subdomains of the SF-36® improved in the octreotide group (physical role: from 60 to 74, p=0.04; bodily pain: from 68 to 76, p<0.02).3

The single RCT that assessed the impact of everolimus used a gastrointestinal questionnaire and a EuroQol Research Foundation questionnaire.22 While this revealed an improvement in both arms of the trial, there was no difference between the octreotide monotherapy and octreotide/everolimus dual therapy group.

Adverse effects

None of the studies found somatostatin analogues to have any serious adverse effects. The most common side effects of somatostatin analogues were abdominal cramps and loose stools.3

The trial of everolimus/octreotide versus octreotide reported serious adverse events in three patients, which required cessation of treatment in the everolimus/octreotide group.22 These included anaemia, abdominal pain and ascites in one patient, and perioral numbness and tingling in another two patients. Symptoms resolved in all three patients after discontinuation of treatment.

Discussion

Our aim was to systematically review the literature on the medical management of PCLD. The available literature indicates that somatostatin analogues are effective and reduce liver volume. The results suggest that liver volumes reduce during the first six months to one year of treatment with somatostatin analogues, following which they plateau and revert back to baseline after cessation of therapy. Interestingly, the reduction in liver volumes was associated with only a modest improvement in QoL. These findings were supported by the results of three small but well designed RCTs and two further case series. On the other hand, there is little evidence to support the use of mTOR inhibitors at present.

PCLD is a benign condition but it results in a significant impact on QoL and nutritional status. Since hepatocyte function itself is maintained, patients do not progress to develop hepatic insufficiency, and one of the primary indications of treatment is therefore to achieve symptom control and improve QoL.

The results of our review indicate that although medical management with somatostatin analogues results in a significant reduction in liver volume, there is only a modest improvement in QoL and symptoms. Furthermore, the studies that assessed the impact of somatostatin analogues on QoL included patients with concomitant polycystic kidney disease as a part of ADPKD syndrome, and their results showed a reduction in both renal and hepatic volumes. This suggests that the improvement seen in QoL cannot be attributed solely to the reduction in liver volumes. These aspects would have to be borne in mind prior to commencement of treatment, especially in patients who have isolated PCLD given that the prime indication for treatment is to provide symptomatic relief and improve QoL.

On the other hand, surgical management can result in considerable improvement in symptoms in the majority of the patients although there is a high rate of recurrence of hepatic cysts and associated symptoms; fenestration of cysts has been shown to result in 92% of patients being symptom free but symptomatic cysts can recur in up to 22% of patients.24 Similarly, liver resection has been reported to achieve symptom relief in 86% of patients but cysts recur in 34%.8 While these measures result in significant improvement, they also carry significant risks.24

Based on the results of this review, certain suggestions can be made regarding the medical management of PCLD. One strategy would be to initiate medical therapy early during the course of the disease before QoL has been influenced. This may prevent progression of the disease and make future surgical interventions unnecessary. Another logical time to commence medical treatment may be following surgical interventions, when somatostatin analogues may delay the recurrence of symptomatic cysts. These strategies can also be used to guide future research to formulate the best possible therapy for PCLD.

Study limitations

Our review has some limitations. First, a meta-analysis of the trials was not performed. Although this would have been theoretically possible, it was not conducted owing to the heterogeneity of the studies. Of the three RCTs on somatostatin analogues, two used long acting octreotide2,18 while the third used lanreotide.17 Furthermore, the outcomes were reported at different intervals ranging from six months to one year in the RCTs and up to two years in the case series. Second, the patient numbers for the studies included in this review were relatively small. However, this may be a reflection of the uncommon condition being investigated.

Conclusions

The current literature supports the use of somatostatin analogues for reducing liver volume in PCLD although this has only a limited impact on QoL. These findings suggest that an initial period of medical management early in the disease course may be attempted. While this may not result in effective symptom relief, it may halt disease progression and obviate the need for surgical therapy.

References

- 1.Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Diagnosis and management of polycystic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; : 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolau C, Torra R, Badenas C et al. . Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2: assessment of US sensitivity for diagnosis. Radiology 1999; : 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ et al. . Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; : 1,052–1,061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int 2009; : 149–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH et al. . The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; : 5,466–5,471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherstha R, McKinley C, Russ P et al. . Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectively stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology 1997; : 1,282–1,286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gevers TJ, Inthout J, Caroli A et al. . Young women with polycystic liver disease respond best to somatostatin analogues: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology 2013; : 357–365.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drenth JP, Chrispijn M, Nagorney DM et al. . Medical and surgical treatment options for polycystic liver disease. Hepatology 2010; : 2,223–2,230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Keimpema L, De Koning DB, Van Hoek B et al. . Patients with isolated polycystic liver disease referred to liver centres: clinical characterization of 137 cases. Liver Int 2011; : 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirchner GI, Rifai K, Cantz T et al. . Outcome and quality of life in patients with polycystic liver disease after liver or combined liver-kidney transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006; : 1,268–1,277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macutkiewicz C, Plastow R, Chrispijn M et al. . Complications arising in simple and polycystic liver cysts. World J Hepatol 2012; : 406–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waanders E, van Keimpema L, Brouwer JT et al. . Carbohydrate antigen 19–9 is extremely elevated in polycystic liver disease. Liver Int 2009; : 1,389–1,395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takei R, Ubara Y, Hoshino J et al. . Percutaneous transcatheter hepatic artery embolization for liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; : 744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park HC, Kim CW, Ro H et al. . Transcatheter arterial embolization therapy for a massive polycystic liver in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. J Korean Med Sci 2009; : 57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Adam R et al. . Excellent survival after liver transplantation for isolated polycystic liver disease: an European Liver Transplant Registry study. Transpl Int 2011; : 1,239–1,245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcea G, Rajesh A, Dennison AR. Surgical management of cystic lesions in the liver. ANZ J Surg 2013; : 516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al. . Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; : 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R et al. . Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2009; : 1,661–1,668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caroli A, Antiga L, Cafaro M et al. . Reducing polycystic liver volume in ADPKD: effects of somatostatin analogue octreotide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; : 783–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page L et al. . Somatostatin analog therapy for severe polycystic liver disease: results after 2 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; : 3,532–3,539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chrispijn M, Nevens F, Gevers TJ et al. . The long-term outcome of patients with polycystic liver disease treated with lanreotide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; : 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrispijn M, Gevers TJ, Hol JC et al. . Everolimus does not further reduce polycystic liver volume when added to long acting octreotide: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol 2013; : 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian Q, Du H, King BF et al. . Sirolimus reduces polycystic liver volume in ADPKD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; : 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Temmerman F, Missiaen L, Bammens B et al. . Systematic review: the pathophysiology and management of polycystic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; : 702–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]