Abstract

Background

Many studies have reported the oncological outcomes between open radical nephroureterectomy (ONU) and laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy (LNU) of upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). However, few data have focused on the oncological outcomes of LNU in the subgroup of localized and/or locally advanced UTUC (T1–4/N0-X). The purpose of this study was to compare the oncological outcomes of LNU vs. ONU for the treatment in patients with T1–4/N0-X UTUC.

Methods

We collected and analyzed the data and clinical outcomes retrospectively for 265 patients who underwent radical nephroureterectomy for T1–4/N0-X UTUC between April 2000 and April 2013 at two Chinese tertiary hospitals. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox’s proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results

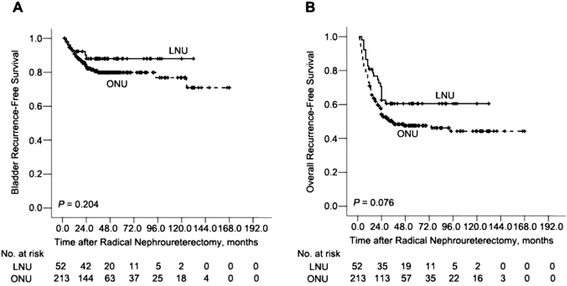

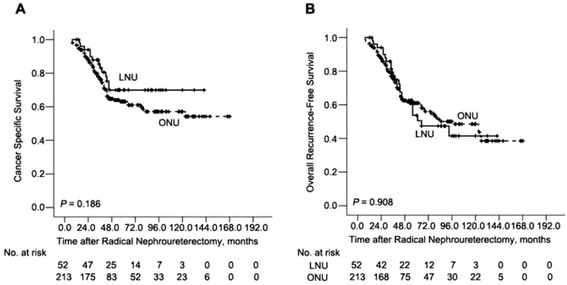

The mean patient age was 62.0 years and the median follow-up was 60.0 months. Of the 265 patients, 213 (80.4%) underwent conventional ONU, and 52 (19.6%) patients underwent LNU. The groups differed significantly in their presence of previous hydronephrosis, presence of previous bladder urothelial carcinoma, and management of distal ureter (P < 0.05). The predicted 5-year intravesical recurrence- free survival (RFS) (79% vs. 88%, P = 0.204), overall RFS (47% vs. 59%, P = 0.076), cancer-specific survival (CSS) (63% vs. 70%, P = 0.186), and overall survival (OS) (61% vs. 55%, P = 0.908) rates did not differ between the ONU and LNU groups. Multivariable Cox proportional regression analysis showed that surgical approach was not significantly associated with intravesical RFS (odds ratio [OR] 1.23, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.46–3.65, P = 0.622), Overall RFS (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.54–1.83, P = 0.974), CSS (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.616–3.13, P = 0.444), or OS (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.81–3.17, P = 0.17).

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective study showed no statistically significant differences in intravesical RFS, overall RFS, CSS, or OS between the laparoscopy and the open groups. Thus, LNU can be an alternative to the open procedure for T1–4/N0-X UTUC. Further studies, including a multi-institutional, prospective study are required to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Upper tract urothelial carcinoma, Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy, Open radical nephroureterectomy, Recurrent, Survival, Oncological, Outcomes

Background

Upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is a relatively rare malignancy. It is estimated to comprise 10% of all renal tumors and 5% of urothelial carcinomas overall [1]. Open radical nephroureterectomy (ONU), with excision of the ipsilateral bladder cuff, is the standard treatment for UTUC [2, 3]. However, laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy (LNU), first performed by Clayman et al. in 1991, has emerged as an accepted minimally invasive treatment alternative to ONU [4]. Subsequently, there have been numerous retrospective reports comparing the oncological outcomes between ONU and LNU [5–18] and one prospective series [19]. To date, none of the studies have shown a significant difference between the techniques in terms of overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), and cancer-specific survival (CSS). Only one study showed that there was a trend toward an independent association between surgical approach and RFS [13], and three studies showed a higher risk of intravesical RFS with LNU [7, 20, 21]. However, these studies focused on the oncological outcomes among the entire cohort of UTUC patients. Especially, they included a great many pTa stage and organ-confined UTUC. As experience with LNU grows, case selection has expanded to include more complex cases, resulting in carefully selected localized and/or locally advanced UTUC and larger tumors being operated on laparoscopically. However, until recently, only one study has focused on the oncological outcomes of LNU in the subgroup of localized and/or locally advanced UTUC [22]. Hence, the present study aimed to compare intravesical RFS, overall RFS, CSS, and OS between ONU and LNU for localized and/or locally advanced UTUC (T1–4/N0-X), performed in two Chinese tertiary teaching hospitals.

Methods

Patients

After institutional review board approval was obtained, a total of 265 consecutive patients, who were identified as having localized and/or locally advanced UTUC (T1–4/N0-X), and subsequently underwent ONU or LNU between April 2000 and April 2013 in The Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, were investigated in this study. Exclusion criteria were the presence of any known metastatic disease at the time of surgery, and radical cystectomy with concomitant radical nephroureterectomy (RNU). All patients had undergone computed tomography, and/or intravenous urography, and/or cystoscopy, and/or urine cytology. Diagnostic ureteroscopy with biopsies has been used to stage tumors accurately in some patients. In addition, none of the patients had received preoperative chemotherapy.

Surgical procedures

Surgery was performed by surgeons according to the standard criteria for RNU. The ONU was performed as either a double-access incision: a loin incision and an iliac incision; or a midline incision was performed from the subxiphoid down to the pelvis. The kidney, Gerota fascia, perinephric fat, the entire length of ureter, and the bladder cuff were excised en bloc. Regional lymphadenectomy was generally performed if lymph nodes were abnormal on preoperative computed tomography or if they were palpable intra-operatively. Extended lymphadenectomy was not performed routinely. The LNU was performed using the retroperitoneal or transperitoneal approach. The range of resection was technically as the same as in the ONU. The patients were fully informed with regard to the surgical approach (laparoscopic vs. open surgery) and its possible complications, and the choice of choice of surgical procedure was nonrandomized; it depended on patient and surgeon preference and experience. In the laparoscopic group, only one patient converted to open surgery. Distal ureter management approaches were categorized as follows: (1) extravesical ureter; (2) open intravesical; and (3) endoscopic.

Pathological and clinical evaluation

All surgical specimens were processed according to standard pathological procedures and anatomical pathologists at two institutions reviewed all slides. Centralized pathological review and reclassification of specimens was not performed. Tumors were staged according to the 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification system, and graded according to the 2004 World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology (WHO/ISUP) consensus classification. The tumor site was defined as renal pelvis, ureter, or both renal pelvis and ureter. Tumor multifocality was defined as the synchronous presence of two or more pathologically confirmed tumors in any upper urinary tract location (renal pelvis or ureter). Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) was defined as the unequivocal presence of tumor cells within an endothelium-lined space, with no underlying muscular walls.

Follow-up regimen

Patients were generally followed-up every 3 months for 2 years after RNU, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and annually thereafter. Patients’ histories were taken, and they underwent a physical examination, routine blood evaluation, urinary cytology, chest radiography, cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, and radiographic evaluation of the contralateral upper urinary tract at each visit. Elective bone scans, computerized tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging were performed when indicated clinically.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). We compared the clinical and pathological characteristics of the two surgical technique groups (ONU vs. LNU) using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. The primary end-points were intravesical RFS, overall RFS, CSS, and OS. Intravesical recurrences included recurrences within the bladder only. Overall recurrent disease included recurrences within the bladder, as well as contralateral recurrences, tumor relapse in the operative field, regional lymph nodes, port site metastasis, and/or distant metastasis. CSS was defined as the time interval between the date of RNU and the end point, including death or censoring. We defined “OS time” as the period between the date of the first operation for the original disease and the date of patient death (from any cause). Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was applied to compare survival curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to determine the association between surgical approach and clinical outcomes. All reported P-values were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients

The study cohort comprised 265 assessable patients. The ONU was performed in 213 (80.4%) vs. LNU in 52 (19.6%) patients. The clinical and pathological details for each of the groups are presented in Table 1. The open surgery preferred the presence of previous hydronephrosis, absence of previous bladder urothelial carcinoma, and underwent extravesical management of the distal ureter (P < 0.05 for all) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of 265 patients treated with either ONU or LNU for UTUC

| Clinical or pathological characteristic | Total cases (n = 265) | Type of procedure | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONU (n = 213) | LNU (n = 52) | |||

| Mean age (SD), years | 62.0 (10.7) | 62.5 (10.7) | 60.2 (10.7) | 0.167a |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.445b | |||

| Male | 198 (74.7) | 157 (73.7) | 41 (78.8) | |

| Female | 67 (25.3) | 56 (26.3) | 11 (21.2) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.207b | |||

| No | 158 (59.6) | 131 (61.5) | 27 (51.9) | |

| Yes | 107 (40.4) | 82 (38.5) | 25 (48.1) | |

| Previous hydronephrosis, n (%) | 0.032 b | |||

| No | 89 (33.6) | 65 (30.5) | 24 (46.2) | |

| Yes | 176 (66.4) | 148 (69.5) | 28 (53.8) | |

| Previous bladder urothelial carcinoma, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| No | 225 (84.9) | 201 (94.4) | 24 (46.2) | |

| Yes | 40 (15.1) | 12 (5.6) | 28 (53.8) | |

| Concomitant bladder urothelial carcinoma, n (%) | 0.274b | |||

| No | 221 (83.4) | 175 (82.2) | 46 (88.5) | |

| Yes | 44 (16.6) | 38 (17.8) | 6 (11.5) | |

| Laterality, n (%) | 0.598b | |||

| Left | 134 (50.6) | 106 (49.8) | 28 (53.8) | |

| Right | 131 (49.4) | 107 (50.2) | 24 (46.2) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.070b | |||

| Renal pelvis | 119 (44.9) | 89 (41.8) | 30 (57.7) | |

| Ureter | 129 (48.7) | 108 (50.7) | 21 (40.4) | |

| Renal pelvis and ureter | 17 (6.4) | 16 (7.5) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Mean tumor size (SD), cm | 3.8 (2.0) | 3.9 (2.1) | 3.3 (1.4) | 0.076a |

| Tumor focality, n (%) | 0.453b | |||

| Unifocal | 156 (58.9) | 123 (57.7) | 33 (63.5) | |

| Multifocal | 109 (41.1) | 90 (42.3) | 19 (36.5) | |

| LVI, n(%) | 0.964b | |||

| No | 193 (72.8) | 155 (72.8) | 38 (73.1) | |

| Yes | 72 (27.2) | 58 (27.2) | 14 (26.9) | |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | 0.570b | |||

| Low | 103 (38.9) | 81 (38.0) | 22 (42.3) | |

| High | 162 (61.1) | 132 (62.0) | 30 (57.7) | |

| pT stage, n (%) | 0.546b | |||

| pT1 | 85 (32.1) | 65 (30.5) | 20 (38.5) | |

| pT2 | 56 (21.1) | 46 (21.6) | 10 (19.2) | |

| pT3/pT4 | 124 (46.8) | 102 (47.9) | 22 (42.3) | |

| pN stage, n (%) | 0.613b | |||

| pN0 | 109 (41.1) | 86 (40.4) | 23 (44.2) | |

| pNx | 156 (58.9) | 127 (59.6) | 29 (55.8) | |

| Distal ureter management, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| Extravesical | 58 (21.9) | 55 (25.8) | 3 (8.9) | |

| Open intravesical | 154 (58.1) | 139 (65.3) | 15 (28.8) | |

| Endoscopic | 53 (20.0) | 19 (8.9) | 34 (65.4) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 0.945b | |||

| No | 208 (78.5) | 167 (78.4) | 41 (78.8) | |

| Yes | 57 (21.5) | 46 (21.6) | 11 (21.2) | |

Bold values indicate that P-value ≤ 0.05, and considered statistically significant. ONU open radical nephroureterectomy, LNU laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy, UTUC upper tract urothelial carcinoma, LVI lymphovascular invasion, SD standard deviation

ªstudent’s test

bchi-square test

Survival analysis

At last follow-up, there were 46 (17.4%) bladder recurrences, including 40 (18.8%) in the ONU group and six (11.5%) in the LNU group. The 5-year intravesical RFS estimates for the ONU and LNU groups were 79% and 88%, respectively (P = 0.204) (Fig. 1a). The total number of recurrence in the ONU and LNU groups were 109 (51.1%) and 20 (38.5%), respectively. Overall RFS for the ONU and LNU groups at 5 years were 47% and 59%, respectively (P = 0.076) (Fig. 1b). In all, 84 patients (31.7%) patients suffered disease progression and metastasis during the study period, including 71 (33.3%) in the ONU group and 13 (25.0%) in the LNU group. Estimated 5-year CSS estimates for ONU and LNU groups were 63% and 70%, respectively, which was non-significant (P = 0.186) (Fig. 2a). In the open group, 84 (39.4%) patients died (from any cause). The 5-year OS rate was 61%. Death occurred (from any cause) in 23 patients (44.2%) in the laparoscopy group. The 5-year OS rate was 55%. No statistically significant difference was found for the OS rate between the two groups (P = 0.908) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Intravesical recurrence-free survival (a) and Overall recurrence-free survival rates (b) in 265 patients treated with either ONU (n = 213) or LNU (n = 52) for UTUC

Fig. 2.

Cancer-specific survival (a) and Overall survival rates (b) in 265 patients treated with either ONU (n = 213) or LNU (n = 52) for UTUC

Predictors of higher intravesical RFS rate on multivariate analysis included concomitant bladder urothelial carcinoma (odds ratio [OR] 2.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.22–5.99, P = 0.014), undergoing extravesical management of distal ureter (P < 0.001), and not having received adjuvant chemotherapy (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.09–0.90, P = 0.033) (Table 2). However, there was no association between surgical approach and intravesical RFS in multivariate cox regression (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.46–3.65, P = 0.622) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable cox regression models predicting intravesical RFS and Overall RFS of 265 patients with UTUC after radical nephroureterectomy

| Variable | Intravesical RFS |

Overall RFS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, continuous | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.359 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.239 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.981 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.232 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1 | 0.181 | 1 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.258 |

| Female | 0.59 (0.28–1.3) | 0.45 (0.19–1.07) | 1.02 (0.69–1.50) | 0.77 (0.48–1.22) | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.273 | 1 | 0.357 | 1 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.057 |

| Yes | 1.41 (0.76–2.58) | 1.41 (0.68–2.89) | 1.54 (0.07–2.22) | 1.52 (0.99–2.33) | ||||

| Previous hydronephrosis | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.768 | 1 | 0.269 | 1 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.83 |

| Yes | 1.10 (0.59–2.03) | 0.65 (0.30–1.40) | 1.41 (0.96–2.08) | 0.94 (0.56–1.59) | ||||

| Previous bladder urothelial carcinoma | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.394 | 1 | 0.491 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.291 |

| Yes | 1.56 (0.56–4.7) | 0.65 (0.19–2.24) | 1.10 (0.52–2.37) | 1.60 (0.67–3.84) | ||||

| Concomitant bladder urothelial carcinoma | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.048 | 1 | 0.014 | 1 | 0.369 | 1 | 0.585 |

| Yes | 1.95 (1.01–3.76) | 2.71 (1.22–5.99) | 1.23 (1.79–1.91) | 1.15 (0.70–1.89) | ||||

| Laterality | ||||||||

| Left | 1 | 0.276 | 1 | 0.573 | 1 | 0.789 | 1 | 0.534 |

| Right | 1.38 (0.77–2.48) | 1.20 (0.64–2.24) | 0.95 (0.68–1.35) | 1.13 (0.78–1.64) | ||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Renal pelvis | 1 | 0.093 | 1 | 0.129 | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Ureter | 1.67 (0.89–3.17) | 1.57 (0.65–3.78) | 1.25 (0.86–1.80) | 1.60 (0.96–2.67) | ||||

| Renal pelvis and ureter | 2.82 (1.02–7.78) | 3.72 (1.04–13.25) | 3.15 (1.74–5.71) | 3.52 (1.70–7.26) | ||||

| Tumor size, continuous | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 0.209 | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 0.353 | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | 0.112 | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 0.682 |

| Tumor focality | ||||||||

| Unifocal | 1 | 0.608 | 1 | 0.757 | 1 | 0.015 | 1 | 0.492 |

| Multifocal | 1.17 (0.65–2.09) | 1.12 (0.56–2.23) | 1.54 (1.09–2.17) | 1.15 (0.77–1.72) | ||||

| LVI | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.582 | 1 | 0.746 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 0.83 (0.42–1.63) | 0.89 (0.43–1.83) | 2.20 (1.54–3.13) | 2.03 (1.39–2.96) | ||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low | 1 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.525 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| High | 0.97 (0.54–1.74) | 0.79 (0.39–1.62) | 3.72 (2.41–5.73) | 2.47 (1.51–4.03) | ||||

| pT stage | ||||||||

| pT1 | 1 | 0.434 | 1 | 0.471 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| pT2 | 1.48 (0.70–3.10) | 1.18 (0.52–2.67) | 1.54 (0.86–2.76) | 1.72 (1.06–3.03) | ||||

| pT3/pT4 | 0.96 (0.48–1.93) | 1.67 (0.73–3.78) | 3.46 (2.18–5.50) | 2.57 (1.47–4.48) | ||||

| pN stage | ||||||||

| pN0 | 1 | 0.097 | 1 | 0.308 | 1 | 0.489 | 1 | 0.677 |

| pNx | 1.73 (0.91–3.28) | 1.45 (0.71–2.94) | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) | 1.09 (0.74–1.61) | ||||

| Distal ureter management | ||||||||

| Extravesical | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.129 |

| Open intravesical | 0.32 (0.18–0.59) | 0.25 (0.13–0.50) | 0.63 (0.43–0.94) | 0.73 (0.47–1.12) | ||||

| Endoscopic | 0.17 (0.06–0.49) | 0.11 (0.03–0.42) | 0.46 (0.27–0.79) | 0.52 (0.27–1.01) | ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.043 | 1 | 0.033 | 1 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.194 |

| Yes | 0.35 (0.12–0.97) | 0.28 (0.09–0.90) | 1.52 (1.03–2.26) | 0.74 (0.46–1.17) | ||||

| Type of procedure | ||||||||

| ONU | 1 | 0.211 | 1 | 0.622 | 1 | 0.082 | 1 | 0.974 |

| LNU | 0.58 (0.25–1.34) | 1.23 (0.46–3.65) | 0.66 (0.41–1.06) | 0.99 (0.54–1.83) | ||||

Bold values indicate that P-value ≤ 0.05, and considered statistically significant. ONU open radical nephroureterectomy, LNU laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy, UTUC upper tract urothelial carcinoma, LVI lymphovascular invasion, RFS recurrence-free survival, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Meanwhile, in the multivariate analysis, the type of surgery was not an independent predictor of overall RFS (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.54–1.83, P = 0.974) (Table 2). However, four clinical pathological parameters were identified as probable predictors of overall RFS in multivariate Cox regression models: tumor location (P = 0.003), LVI (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.39–2.96, P < 0.001), tumor grade (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.51–4.03, P < 0.001), and pT stage (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate analysis examining predictors of CSS and OS in the cohort. On multivariate analysis, LVI, tumor grade, and pT stage were the only independent predictors of CSS (P < 0.05 for all; Table 3). Similarly, LVI, tumor grade, and pT stage were the independent predictors of OS (P < 0.05 for all; Table 3). The type of procedure, ONU or LNU, was not an independent predictor of CSS (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.61–3.13, P = 0.444; Table 3) or OS (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.82–3.17, P = 0.17; Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable cox regression models predicting CSS and OS of 265 patients with UTUC after radical nephroureterectomy

| Variable | CSS | OS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, continuous | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.282 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.641 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.011 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.159 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1 | 0.681 | 1 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.827 | 1 | 0.66 |

| Female | 1.11 (0.68–1.80) | 1.03 (0.56–1.88) | 1.05 (0.67–1.64) | 0.89 (0.53–1.50) | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.171 | 1 | 0.302 | 1 | 0.113 | 1 | 0.119 |

| Yes | 1.37 (0.87–2.14) | 1.34 (0.77–2.36) | 1.38 (0.93–2.04) | 1.46 (0.91–2.34) | ||||

| Previous hydronephrosis | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.115 | 1 | 0.439 | 1 | 0.058 | 1 | 0.149 |

| Yes | 1.47 (0.91–2.38) | 1.30 (0.67–2.50) | 1.51 (0.99–2.32) | 1.51(0.86–2.65) | ||||

| Previous bladder urothelial carcinoma | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.606 | 1 | 0.833 | 1 | 0.926 | 1 | 0.966 |

| Yes | 1.24 (0.54–2.86) | 1.23 (0.37–3.48) | 0.96 (0.42–2.19) | 1.02 (0.39–2.69) | ||||

| Concomitant bladder urothelial carcinoma | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 0.636 | 1 | 0.712 | 1 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.411 |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.66–1.97) | 1.13 (0.60–2.14) | 0.83 (0.49–1.41) | 0.77 (0.42–1.43) | ||||

| Laterality | ||||||||

| Left | 1 | 0.512 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.772 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Right | 0.87 (0.56–1.33) | 1.50 (0.91–2.45) | 0.95 (0.65–1.38) | 1.30 (0.85–1.99) | ||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Renal pelvis | 1 | 0.029 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.458 | |

| Ureter | 1.35 (0.85–2.15) | 1.77 (0.93–3.37) | 1.15 (0.77–1.72) | 1.31 (0.76–2.25) | ||||

| Renal pelvis and ureter | 2.61 (1.28–5.34) | 2.69 (1.08–6.70) | 1.62 (0.79–3.32) | 1.63 (0.70–3.78) | ||||

| Tumor size, continuous | 1.13 (1.03–1.26) | 0.015 | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 0.268 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 0.083 | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) | 0.364 |

| Tumor focality | ||||||||

| Unifocal | 1 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.871 | 1 | 0.085 | 1 | 0.694 |

| Multifocal | 1.49 (0.97–2.28) | 0.96 (0.58–1.60) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | 1.09 (0.70–1.70) | ||||

| LVI | ||||||||

| No | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 2.20 (1.54–3.13) | 2.0 (1.26–3.17) | 2.20 (1.50–3.23) | 1.88 (1.25–2.83) | ||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low | 1 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| High | 11.23 (4.89–25.81) | 6.95 (2.87–16.83) | 4.03 (2.47–6.56) | 2.59 (1.50–4.49) | ||||

| pT stage | ||||||||

| pT1 | 1 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.004 | |

| pT2 | 1.91 (0.75–4.84) | 1.69 (1.11–2.59) | 1.36 (0.69–2.70) | 1.40 (0.91–2.14) | ||||

| pT3/pT4 | 7.40 (3.55–15.43) | 2.83 (1.20–6.66) | 4.12 (2.43–6.99) | 2.29 (1.21–4.36) | ||||

| pN stage | ||||||||

| pN0 | 1 | 0.429 | 1 | 0.494 | 1 | 0.785 | 1 | 0.645 |

| pNx | 0.84 (0.55–1.29) | 0.84 (0.51–1.38) | 0.95 (0.64–1.40) | 0.90 (0.59–1.39) | ||||

| Distal ureter management | ||||||||

| Extravesical | 1 | 0.434 | 1 | 0.277 | 1 | 0.538 | 1 | 0.921 |

| Open intravesical | 1.09 (0.65–1.85) | 1.35 (0.75–2.41) | 0.77 (0.49–1.22) | 0.93 (0.57–1.52) | ||||

| Endoscopic | 0.73 (0.36–1.48) | 0.74 (0.30–1.84) | 0.87 (0.50–1.50) | 0.86 (0.41–1.82) | ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.111 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.331 |

| Yes | 2.93 (1.88–4.56) | 1.54 (0.90–2.63) | 2.13 (1.40–3.22) | 1.28 (0.78–2.09) | ||||

| Type of procedure | ||||||||

| ONU | 1 | 0.191 | 1 | 0.444 | 1 | 0.909 | 1 | 0.17 |

| LNU | 0.67 (0.37–1.22) | 1.38 (0.61–3.13) | 1.03 (0.65–1.63) | 1.61 (0.82–3.17) | ||||

Bold values indicate that P-value ≤ 0.05, and considered statistically significant. ONU open radical nephroureterectomy, LNU laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy, UTUC upper tract urothelial carcinoma, LVI lymphovascular invasion, CSS cancer specific survival, OS overall survival, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

Clayman et al. performed the first successful LNU in 1991 [4]. Multiple reports have since described the efficacy of LNU for favorable-risk UTUC patients regarding cancer control [5–19]. In recent years, experienced surgeons have expanded their criteria for LNU for large or locally advanced UTUC, which indicated the effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery. To compare the efficacy of LNU and ONU in localized and/or locally advanced UTUC, we performed the present study, including 265 patients with T1–4/N0-X UTUC (213 ONU vs. 52 LNU) treated with RNU. The Kaplan-Meier plot illustrated no significant difference in survival between the two groups of different procedures. Multivariate analysis suggested the equivalence of LNU and ONU in terms of intravesical RFS, overall RFS, CSS, and OS. During the later courses of our study, Kim et al. [22] reported that the 5-year OS and CSS rates were lower in the LNU group than in the ONU group in patients with locally advanced UTUC. Furthermore, on multivariable analysis, LNU was found to be an independent predictor of poorer OS and CSS than ONU. However, the study has some limitations: On the one hand, the cohort patients included N+ disease. On the other hand, the study did not analyze the cigarette smoking status, despite the fact that exposure to smoking is a significant risk factor for bladder urothelial carcinoma as well as UTUC. Thus, the comparison between Kim’s study and our study is difficult to make.

It is essential to follow the oncological principles and the established surgery procedure for laparoscopic surgery in urothelial carcinomas [8, 11, 14]. According to previously published papers, tumors cells may undergo retroperitoneal metastatic dissemination and dissemination along the trocar pathway under pneumoperitoneal circumstances during operation. Initial researchers despised laparoscopic operation in urothelial carcinomas because the high-pressure environment of pneumoperitoneum was thought to promote tumor dissemination and recurrence. To our best knowledge, only 12 cases of laparoscopic port-site seeding are available in English literature [23]. In our study, only one case was seen in our early experiences, which may be associated with the limited use of laparoscopic bags in the early days. Nowadays, precautionary measures have been taken into consideration to prevent potential tumor spillage. It has been stressed that direct contact between the instrument and the tumor should be forbidden during dissection. Besides, LNU must be accomplished in a closed system.

In patients with organ-confined UTUC, LNU has the advantage of minimal invasiveness and has oncological outcomes comparable to those of ONU. However, its effectiveness in patients with localized and/or locally advanced diseases remains to be proven, and the results were contradictory. Our findings were consistent with results from one single center study [10] and two recent multi-institutional studies [4, 9], which showed no independent association between surgical approach and survival, in both organ-confined and advanced UTUC patients. Unfortunately, some authors reported that relative to ONU, LNU was associated with an adverse prognosis in advanced stage patients. Fairey and colleagues [13] published a multi-institutional retrospective study comparing ONU and LNU in 849 patients. These authors report equivalent OS and CSS for the surgical approaches. However, there was a trend toward an independent association between surgical approach and RFS (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98–1.57, P = 0.08). Furthermore, when stratifying by stage on multivariate Cox regression models, LNU was independently associated with poorer RFS in patients with ≤ pT2N0 and pTanyN1-3 disease: however, there was no independent association between surgical approach and RFS in patients with pT3-4 N0 disease. In the only prospective randomized study published in the literature, Simone and colleagues [19] reported 80 UTUC patients treated with ONU (n = 40) and LNU (n=40). After a median follow-up of 44 months, for organ-confined disease, the two groups did not differ significantly in the rates of intravesical RFS and CSS. However, when matched for pT3 and high-grade tumors, CSS and metastasis-free survival were significantly different between the two groups, in favor of ONU.

However, the conclusions based on previous results are underpowered because of the different statistical models used. The factors of UTUC tumor location [24, 25], previous bladder tumor history [26, 27], and previous hydronephrosis [28, 29] should be included in the model because the predictive significance of these factors remains controversial. Additionally, cigarette smoking status should be included in the analysis because exposure to smoking is a significant risk factor for bladder urothelial carcinoma as well as UTUC [30]. Furthermore, imbalances are apparent in some of these important series [9, 11, 13]. The LNU group contained tumors at lower stages and they had a lower rate of LVI. These differences, were statistically significant. This may be compensated for by the multivariate analysis and further corrected using various statistical techniques; nevertheless, it reflects significant patient selection in which, generally speaking, LNU was avoided in the higher stage cases. Thus, because of the smaller proportion of higher stage cases performed laparoscopically, the overall outcome was skewed by the good prognosis of the lower stage cases. In comparison with previous results, our groups were better matched for prognostic factors, such as tumor stage, grade, and LVI, and we include some controversial elements, such as tumor location, previous bladder tumor history, and previous hydronephrosis. Therefore, we could draw more relevant conclusions. In addition, several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, the data were collected retrospectively and reflect the experiences of two institutions. Furthermore, different bladder cuff managements were used between the LNU and ONU groups. Second, the majority of patients were underwent open procedures; moreover, the laparoscopic cohort included those operated on using retroperitoneal and transperitoneal approaches. Third, pathological specimens were not subjected to a centralized review. In additon, the follow-up period was relatively short.

Conclusions

In summary, after a median follow-up of 60.0 months, oncological results were comparable between LNU and ONU for the treatment of localized and/or locally advanced UTUC (T1–4/N0-X). Our data could be used as evidence for equivalent cancer control outcomes between LNU and ONU in patients with T1–4/N0-X UTUC. Further analyses, including randomized trials, are needed to generalize these conclusions to patients with more unfavorable disease characteristics.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (No. 2016JJ6151).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

LYH raised study concepts and participated in study design. JYL together with LYH performed the study. JYL drafted the manuscript. ZL and JT (Jing Tan) collected the clinical data and participated in statistical analysis. JT (Jin Tang), BL, and KY participated in quality control of data and algorithms. YBD, FJZ, YHL and DX critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- LNU

Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy

- LVI

Lymphovascular invasion

- ONU

Radical nephroureterectomy

- OR

Odds ratio

- OS

Overall survival

- RFS

Recurrence-free survival

- RNU

Radical nephroureterectomy

- UTUC

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma

- WHO/ISUP

World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology

Contributor Information

Jian-Ye Liu, Email: liujianye810@163.com.

Ying-Bo Dai, Email: 410849661@qq.com.

Fang-Jian Zhou, Email: zfjsysucc@163.com.

Zhi Long, Email: longzhicsu@163.com.

Yong-Hong Li, Email: liyonghongsys@163.com.

Dan Xie, Email: xiedansys@163.com.

Bin Liu, Email: liubcsu@163.com.

Jin Tang, Email: tangjincsu@163.com.

Jing Tan, Email: tanjingcsu@163.com.

Kun Yao, Email: yaokuncsu@163.com.

Le-Ye He, Email: heleye_csu@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donat SM. Integrating perioperative chemotherapy into the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: strategy versus reality. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:40–7. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roupret M, Babjuk M, Comperat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester RJ, Burger M, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinoma: 2015 update. Eur Urol. 2015;68:868–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayman RV, Kavoussi LR, Figenshau RS, Chandhoke PS, Albala DM. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy: initial clinical case report. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1991;1:343–9. doi: 10.1089/lps.1991.1.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manabe D, Saika T, Ebara S, Uehara S, Nagai A, Fujita R, et al. Comparative study of oncologic outcome of laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and standard nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 2007;69:457–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roupret M, Hupertan V, Sanderson KM, Harmon JD, Cathelineau X, Barret E, et al. Oncologic control after open or laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: a single center experience. Urology. 2007;69:656–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamihira O, Hattori R, Yamaguchi A, Kawa G, Ogawa O, Habuchi T, et al. Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy: a multicenter analysis in Japan. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldert M, Remzi M, Klingler HC, Mueller L, Marberger M. The oncological results of laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell cancer are equal to those of open nephroureterectomy. BJU Int. 2009;103:66–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capitanio U, Shariat SF, Isbarn H, Weizer A, Remzi M, Roscigno M, et al. Comparison of oncologic outcomes for open and laparoscopic nephroureterectomy: a multi-institutional analysis of 1249 cases. Eur Urol. 2009;56:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favaretto RL, Shariat SF, Chade DC, Godoy G, Kaag M, Cronin AM, et al. Comparison between laparoscopic and open radical nephroureterectomy in a contemporary group of patients: are recurrence and disease-specific survival associated with surgical technique? Eur Urol. 2010;58:645–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton TJ, Novara G, Matsumoto K, Kassouf W, Fritsche HM, Artibani W, et al. Oncological outcomes after laparoscopic and open radical nephroureterectomy: results from an international cohort. BJU Int. 2011;108:406–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariane MM, Colin P, Ouzzane A, Pignot G, Audouin M, Cornu JN, et al. Assessment of oncologic control obtained after open versus laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas (UUT-UCs): results from a large French multicenter collaborative study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:301–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairey AS, Kassouf W, Estey E, Tanguay S, Rendon R, Bell D, et al. Comparison of oncological outcomes for open and laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy: results from the Canadian Upper Tract Collaboration. BJU Int. 2013;112:791–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greco F, Wagner S, Hoda RM, Hamza A, Fornara P. Laparoscopic vs open radical nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract urothelial cancer: oncological outcomes and 5-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2009;104:1274–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taweemonkongsap T, Nualyong C, Amornvesukit T, Leewansangtong S, Srinualnad S, Chaiyaprasithi B, et al. Outcomes of surgical treatment for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: comparison of retroperitoneoscopic and open nephroureterectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rassweiler JJ, Schulze M, Marrero R, Frede T, Palou Redorta J, Bassi P. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: is it better than open surgery? Eur Urol. 2004;46:690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bariol SV, Stewart GD, McNeill SA, Tolley DA. Oncological control following laparoscopic nephroureterectomy: 7-year outcome. J Urol. 2004;172:1805–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140995.44338.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart GD, Humphries KJ, Cutress ML, Riddick AC, McNeill SA, Tolley DA. Long-term comparative outcomes of open versus laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract urothelial-cell carcinoma after a median follow-up of 13 years. J Endourol. 2011;25:1329–35. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simone G, Papalia R, Guaglianone S, Ferriero M, Leonardo C, Forastiere E, et al. Laparoscopic versus open nephroureterectomy: perioperative and oncologic outcomes from a randomised prospective study. Eur Urol. 2009;56:520–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui Y, Utsunomiya N, Ichioka K, Ueda N, Yoshimura K, Terai A, et al. Risk factors for subsequent development of bladder cancer after primary transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Urology. 2005;65:279–83. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WW, Huang HY, Liao AC, Shiue YL, Tai HL, Lin CM, et al. Primary urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract: important clinicopathological factors predicting bladder recurrence after surgical resection. Pathol Int. 2009;59:642–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, Ku JH, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Kim HH. Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy is associated with worse survival outcomes than open radical nephroureterectomy in patients with locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol. 2016;34:859–69. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1712-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roupret M, Smyth G, Irani J, Guy L, Davin JL, Saint F, et al. Oncological risk of laparoscopic surgery in urothelial carcinomas. World J Urol. 2009;27:81–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park S, Hong B, Kim CS, Ahn H. The impact of tumor location on prognosis of transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. J Urol. 2004;171:621–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000107767.56680.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Poel HG, Antonini N, van Tinteren H, Horenblas S. Upper urinary tract cancer: location is correlated with prognosis. Eur Urol. 2005;48:438–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akdogan B, Dogan HS, Eskicorapci SY, Sahin A, Erkan I, Ozen H. Prognostic significance of bladder tumor history and tumor location in upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;176:48–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milojevic B, Djokic M, Sipetic-Grujicic S, Grozdic Milojevic I, Vuksanovic A, Nikic P, et al. Prognostic significance of non-muscle-invasive bladder tumor history in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bozzini G, Nison L, Colin P, Ouzzane A, Yates DR, Audenet F, et al. Influence of preoperative hydronephrosis on the outcome of urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract after nephroureterectomy: the results from a multi-institutional French cohort. World J Urol. 2013;31:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0964-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung PH, Krabbe LM, Darwish OM, Westerman ME, Bagrodia A, Gayed BA, et al. Degree of hydronephrosis predicts adverse pathological features and worse oncologic outcomes in patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:981–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crivelli JJ, Xylinas E, Kluth LA, Rieken M, Rink M, Shariat SF. Effect of smoking on outcomes of urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2014;65:742–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.