Abstract

Background

Mounting evidence indicated that the elevated serum uric acid level was associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI). Our goal was to systematically evaluate the correlation of serum uric acid (SUA) level and incidence of AKI by longitudinal cohort studies.

Methods

We searched electronic databases and the reference lists of relevant articles. 18 cohort studies with 75,200 patients were analyzed in this random-effect meta-analysis. Hyperuricemia was defined as SUA levels greater than 360-420 μmol/L (6–7 mg/dl), which was various according to different studies. Data including serum uric acid, serum creatinine, and incidence of AKI and hospital mortality were summarized using random-effects meta-analysis.

Results

The hyperuricemia group significantly exerted a higher risk of AKI compared to the controls (odds ratio OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.76-2.86, p < 0.01). Furthermore, there is less difference of the pooled rate of AKI after cardiac surgery between hyperuricemia and control group (34.3% vs 29.7%, OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.96-1.60, p = 0.10), while the rates after PCI were much higher in hyperuricemia group than that in control group (16.0% vs 5.3%, OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.93-5.45, p < 0.01). In addition, there were significant differences in baseline renal function at admission between hyperuricemia and control groups in most of the included studies. The relationship between hyperuricemia and hospital mortality was not significant. The pooled pre-operative SUA levels were higher in AKI group than that in the non-AKI group.

Conclusions

Elevated SUA level showed an increased risk for AKI in patients and measurements of SUA may help identify risks for AKI in these patients.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Hyperuricemia, Uric acid, Meta-analysis

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs commonly after cardiovascular surgery, in patients with sepsis, and after the administration of various nephrotoxins including contrast agents. The incidence of AKI has a significant effect on the outcomes. Prevention before any procedure is essential because no measures have been proven to effectively treat AKI. Therefore, if high-risk patients could be screened earlier, the clinician still would have opportunities to prevent AKI and further improve outcomes [1, 2].

Uric acid is an end-product of purine degradation and is excreted via kidney. Many epidemiologic studies have suggested that hyperuricemia is associated with hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and the progression of chronic kidney disease [3–5]. In addition, it is found that hyperuricemia is associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) in various statuses [6–9]. This meta-analysis was conducted to estimate whether hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for incidence and prognosis of AKI. This effort hoped to raise awareness of the importance of hyperuricemia in the developing AKI.

Methods

Search strategy and data sources

We performed a computerized search to identify relevant published original studies (1985 to May 2016). Pubmed, Web of Science, Cochrwane Library, OVID and EMBASE databases were searched using medical subject headings (MeSH) or keywords. These words were “acute kidney failure, acute kidney injury, acute kidney dysfunction, acute kidney insufficiency, acute tubular necrosis, acute renal failure, acute renal injury, acute renal dysfunction, or acute renal insufficiency” and “hyperuricemia, or uric acid”. This search was not limited to English language or publication type. We followed a prespecified protocol but this was not registered.

Selection criteria

An initial eligibility screen of all retrieved titles and abstracts was performed, and only studies reporting the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) and AKI were selected for further review. The following included criteria were used for final selection: (1) studies reporting the incidence of AKI and pre-operative SUA Levels, (2) studies using clear definition of AKI, and hyperuricemia, (3) studies providing detailed information about the incidence of AKI, and/or hospital mortality. We restricted our search to clinical studies performed in adult populations. Studies without clear grouping or animal experimental studies were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (X.X.L and H.J.C) examined the studies independently, and disagreement was resolved by discussion. Data extraction included country of origin, year of publication, study period, study design, inclusion criteria, definition of hyperuricemia or grouping according to SUA, conclusions and patient characteristics (age and sex). Hyperuricemia was defined as SUA levels greater than 360-420 μmol/L (6–7 mg/dl), which was various according to different studies. The primary outcomes were odds ratio (OR) of SUA to predict incidence of AKI. The definition of AKI in all these included studied used the AKI network criteria [10] with minor modification and defined as an increase ≥0.3 mg/dL in the serum creatintine level within 48 h in the hospital or ICU (Table 1). The second outcomes included SUA levels in AKI and No-AKI group and hospital mortality in hyperuricemia and control group. The study selection, data extraction and reporting of results were all based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist [11]. The quality of the cohort studies was assessed independently by pairs of two authors, using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [12], which allocates a maximum of 9 points for quality of the selection, comparability, and outcome of study populations. Study quality scores were defined as poor (0–3), fair (4–6), or good (7–9).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Authors (year) | Study period | Country | Study design | Sample size | Mean age (y) | Percentage of Male (%) | Inclusion criteria | Definition of hyperuricemia or grouping according to SUA | Definition of AKI | Mean baseline eGFR in HUA group (ml/min/1.73 m2) | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shacham, et al. (2016) [48] | 2008–2015 | Israel | Retrospective cohort | 1372 | 62 ± 12 | 85 | Acute STEMI patients requiring PCI | <4.7 mg/dl, 4.8–5.6 mg/dl, 5.7–6.6 mg/dl, >6.7 mg/dl | A rise in sCr >0.3 mg/d above the admission sCr within 48 h | 79 ± 19, 75 ± 17, 70 ± 11, 63 ± 20 for 4 groups respectively | Elevated UA levels are an independent predictor of AKI |

| Cheungpasitporn, et al. (2016) [49] | 2011–2013 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 1435 | 62 ± 16 | 60.3 | All hospitalized adult patients without ESRD and AKI at presentation and trauma | <3.4 mg/dl, 3.4–4.5 mg/dl, 4.5–5.8 mg/dl, 5.8–7.6 mg/dl, 7.6–9.4 mg/dl, >9 mg/dl | An increase in sCr ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or ≥1.5 times baseline within 7 days after admission date | 89.5 ± 20.6, 88.1 ± 21.9, 79.3 ± 24.5, 71.7 ± 24.8, 58.6 ± 22.3, 53.2 ± 21.8 for 6 groups respectively | Elevated admission SUA was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital AKI |

| Otomo, et al. (2015) [6] | 1981–2011 | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 59,219 | 58.6 ± 17.9 | 48.4 | All hospitalized patients | The first stratum: SUA ≤2.0 mg/dL; the 12th stratum: SUA >7.0 mg/dL, with SUA levels in each succeeding stratum increasing by increments of 0.5 mg/dL | An increase ≥0.3 mg/dL in the sCr level within 48 h; or ≥1.5 times baseline within the prior 7 days; or urine volume of 0.5 mL/kg/h within 6 h | 102 ± 50, 99 ± 44, 96 ± 45, 93 ± 38, 88 ± 31, 86 ± 34, 81 ± 28, 79 ± 29, 76 ± 28, 73 ± 28, 70 ± 27, 59 ± 34 for 6 groups respectively | SUA level could be an independent risk factor for AKI development in hospitalized patients |

| Liang, et al. (2015) [50] | 2009–2014 | China | Prospective cohort | 59 | 37.3 ± 10.6 | NR | Severe burn | NR | An absolute anincrease in sCr > 0.3 mg/dl from baseline within 48 h after injury | NR | Elevated SUA after injury due to hypoxia is closely correlated with early AKI after severe burns |

| Lee, et al. (2015) [7] | 2006–2011 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | 2,185 | 63.6 ± 9.1 | 74.7 | All patients undergoing CABG | NR | An increase in sCr of ≥0.3 mg/dL or ≥150% from baseline within the first 48 h after operation | NR | Preoperatively Elevated SUA was significantly associated with AKI and improved the ability to predict the development of AKI in patients undergoing CABG |

| Lazzeri, et al. (2015) [51] | 2006–2013 | Italy | Prospective cohort | 329 | 77.2 ± 10.0 | 53.8 | STEMI patients submitted to primary PCI | SUA ≤ 5.9 mg/dl, 6.0–7.4 mg/dl, >7.4 mg/dl | An absolute increase in sCr level of 0.3 mg/dl or more, or a relative increase in sCr level of 50% or more during the ICCU stay | 42.8 ± 14.3, 42.5 ± 13.4, 40.8 ± 12.2 for 3 groups respectively | Uric acid helps in identifying a subset of patients at a higher risk of AKI and 1-year mortality. |

| Gaipov, et al. (2015) [52] | 2011–2012 | Turkey | Prospective cohort | 60 | 56.7 ± 16.4 | 70.0 | Patients undergoing cardiac surgery | NR | An increase in sCr by 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or increase in sCr to 1.5 times baseline | NR | Uric acid seems to predict the progression of AKI and RRT requirement in patients underwent cardiac surgery better than NGAL |

| Barbieri, et al. (2015) [8] | 2007–2011 | Italy | Retrospective cohort | 1,950 | 72.1 ± 8.7 | NR | Patients undergoing coronary angiography and /or angioplasty with GFR ≤ 89 ml/min | SUA ≤ 5.5 mg/dL; 5.6–7.0 mg/dL; ≥7.0 mg/dL | An absolute ≥0.5 mg/dl or a relative ≥25% increase in the sCr level at 24 or 48 h after the procedure | NR | Elevated SUA level is independently associated with an increased risk of CIN |

| Guo, et al. (2015) [53] | 2010–2013 | China | Prospective cohort | 1772 | 64.43 ± 11.35 | 76.5 | Patients who underwent PCI | SUA > 7 mg/dL (417 μmol/L) in males and >6 mg/dL (357 μmol/L) in females. | an increase in sCr of >0.5 mg/dL from the baseline within 48–72 h of contrast exposure | 71.08 ± 24.70 | Hyperuricemia is associated with a risk of CI-AKI. Long-term mortality after PCI was higher in those with hyperuricemia than with normouricemia after adjusting. |

| Joung, et al. (2014) [54] | 2011–2012 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | 1,094 | 63.0 | 62.2 | Patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery | SUA > 6.5 mg/dL (preoperative) (6.0 mg/dL in women and 7.0 mg/dL in men) | An increase ≥0.3 mg/dL in the sCr level or ≥1.5 times baseline within 48 h | NR | Preoperative elevated serum uric acid is an independent risk factor for AKI in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. |

| Xu, et al. (2014) [55] | 2005–2011 | China | Retrospective cohort | 936 | 65.2 ± 4.2 | 54.3 | Old patients (≥60 years) undergoing CPB | SUA ≤ 384.65; 384.66–476.99; ≥477.00 μmol/L (males) SUA ≤ 354.00; 354.01–437.96; ≥437.97 μmol/L (females) | An increase in sCr ≥150% from baseline within the first 7 days after operation | 73.8 ± 17.2, 69.3 ± 14.2, 61.5 ± 15.8 for 3 groups respectively | Pre-operative elevated uric acid is an independent risk factor of AKI after cardiac surgery in elderly patients |

| Liu, et al. (2013) [56] | 2010–2011 | China | Prospective cohort | 788 | 62.8 ± 11.3 | 78.6 | Patients undergoing PCI | SUA >7 mg/dL in males and >6 mg/dL in females | An increase in sCr of ≥ 0.5 mg/dL above the baseline value within 48–72 h after PCI | *Creatinine Clearance: 65 ± 24 ml/min | Hyperuricemia was significantly associated with the risk of CI-AKI in patients with relatively normal serum creatinine after PCI |

| Lapsia, et al. (2012) [57] | 2004–2008 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 190 | 63.9 ± 0.9 | 62.1 | Patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery | SUA ≥7 mg/dL | An absolute increase in sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL from baseline within 48 h after surgery | 47.6 ± 1.8 | Preoperative SUA was associated with increased incidence and risk for AKI |

| Ejaz, et al. (2012) [58] | NR | USA | Prospective cohort | 100 | 61.4 ± 1.4 | 60 | Patients undergoing cardiac surgery with eGFR > 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 | SUA < 4.53 mg/dL, 4.53–5.77 mg/dL, > 5.77 mg/dL | An absolute increase in sCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dL from baseline within 48 h after surgery | NR | Post-operative SUA is associated with an increased risk for AKI and compares well to conventional markers of AKI |

| Park, et al. (2011) [59] | 2006–2009 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | 1,247 | 64.3 ± 11.9 | 62.3 | Patients undergoing PCI | SUA ≥7.0 mg/dl for males and ≥ 6.5 mg/dl for females. | An increase in sCr of ≥0.5 mg/dl or ≥50% over baseline within 7 days of PCI | NR | Hyperuricemia is independently associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and AKI in patients treated with PCI |

| Kim, et al. (2011) [60] | 2007–2008 | Korea | Retrospective cohort | 247 | 46.1 ± 13.7 | 52 | Acute PQ intoxication | SUA ≥7.3 mg/dL in men or ≥5.3 mg/dL in women | An increase in sCr of ≥0.3 mg/dL or ≥150% from baseline within 48 h after admission | NR | Baseline serum uric acid level might be a good clinical marker for patients at risk of mortality and AKI after acute PQ intoxication |

| Ben-Dov, I. Z., et al. (2011) [61] | 1976–1979 | Israel | Retrospective cohort | 2449 | 58.8 | 50 ± 6 | Patients in Lipid Research Clinic cohort | >6.5 mg/dL in men and >5.3 mg/dL in women | NR | 93 ± 18 in men and women | SUA was found to be a strong predictor of acute renal failure |

| Toprak et al. (2006) [62] | 2004–2005 | Turkey | Prospective cohort | 266 | 58.9 ± 7.4 | 61% | Nonemergency diagnostic coronary angiography with Scr > 1.2 mg/dl | >7 mg/dl in men and 6.5 mg/dl in women. | An increase of ≥25% in sCr over baseline within 48 h of coronary angiography | 55.26 ± 13.7 | Patients with hyperuricemia are at risk of developing CIN. |

Abbreviations: SUA serum uric acid, sCr serum creatintine, AKI acute kidney injury, CABG Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, STEMI ST-elevation myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, NGAL neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, GFR glomerular filtration rate, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, CIN contrast-induced nephropathy, CI-AKI contrast-induced acute kidney injury, PQ paraquat, NR not reported

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Review Manager (RevMan, Cochrane Collaboration, version 5.3) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA version 2.0, Biostat) were used to perform the meta-analysis. Pooled estimates were obtained for incidence of AKI and hospital mortality, which were reported using random-effects meta-analysis based on the methods of DerSimonian and Laird [13]. Meta-analyses were performed using OR for dichotomous outcomes. All confidence intervals (CI) were reported at 95%. P-value statistical significance was measured at 0.05. Heterogeneity across trials was evaluated with using theI 2 index and the Q test p value. A p value of less than 0.05 and anI 2 index of more than 25% indicated the presence of interstudy heterogeneity [14]. Publication bias was assessed by constructing a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test.

Results

Study selection

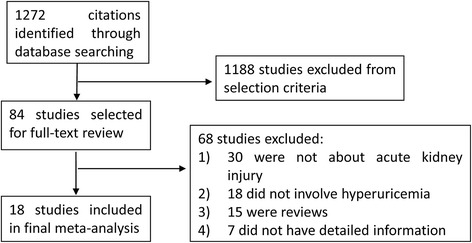

The article selection process is outlined in Fig. 1. The electronic database searches identified 1272 citations. After removal of duplicates and preliminary screening, 84 articles were selected for full-text review for their relevance to this study and 18 studies were included in this systematic review. At the full-text review stage, 30 articles were not about AKI, 18 did not involve hyperuricemia and 15 were review. Seven studies were excluded from the primary meta-analysis as they did not report the detailed information, and the corresponding authors were unable to provide the requisite data. Agreement between investigators at the full-text review stage was excellent as indicated by a κ of 0.8.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of literature search and study selection

Study description and quality assessment

A detailed description of the included studies is provided in Table 1. The included studies were published between 2006 and 2016, and were carried out in a wide range of countries. The total number of patients included in the primary meta-analysis was 75,200 with a median (interquartile range) of 559 (122–1774) patients per study. The detailed information of age and gender was also listed in Table 1. Overall study quality was good with a mean NOS score of 7.5 out of a possible 9 (range, 7–9) and with 11 studies (91.7%) receiving a NOS greater than or equal to 7 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of the studies utilizing the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (Cohort studies)

| Reference (Year) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts onthe basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Follow up long enough | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | ||

| Shacham, et al. (2016) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Cheungpasitporn, et al. (2016) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Otomo, et al. (2015) [6] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Liang, et al. (2015) | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Lee, et al. (2015) [7] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Lazzeri, et al. (2015) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Gaipov, et al. (2015) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Barbieri, et al. (2015) [8] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 7 |

| Guo, et al. (2015) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Joung, et al. (2014) | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Xu, et al. (2014) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Liu, et al. (2013) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Lapsia, et al. (2012) | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Ejaz, etal (2012) [43] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 7 |

| Park, et al. (2011) | ☆ | ☆ | - | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Kim, et al. (2011) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Ben-Dov, I. Z., et al. (2011) | ☆ | ☆ | -- | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | - | 6 |

| Toprakm, et al. (2006) | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

Effects of SUA on the incidence of AKI

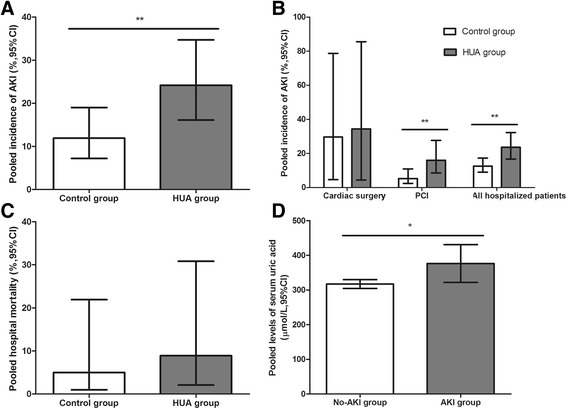

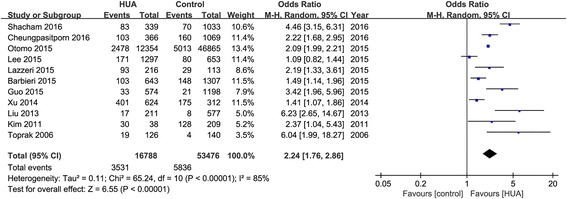

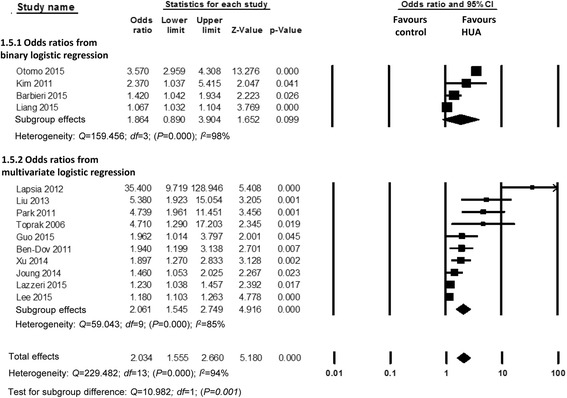

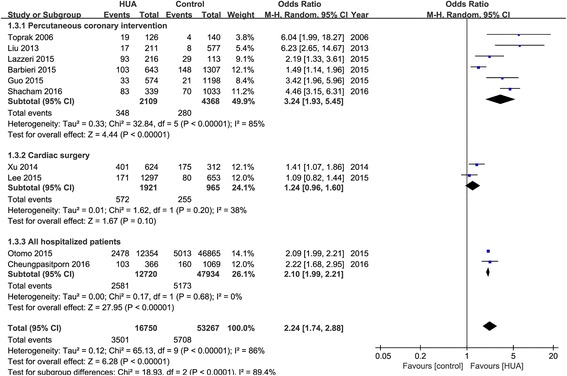

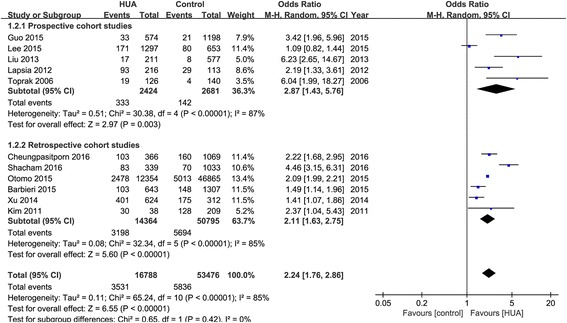

Eleven observational studies with 70,264 patients reported the incidence of AKI. The pooled rates of AKI incidence in hyperuricemia group and control group were 24.2% (95% CI, 16.1-34.7%) and 11.9% (95% CI, 7.2-19.0%) respectively (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.76-2.86, p < 0.00001) (Figs. 2a and 3). Four studies reported ORs of SUA to predict AKI by binary logistic regression and ten studies reported ORs by multiple logistic regression, and the pooled ORs were 1.864 (95% CI 0.890-3.904, p = 0.000) and 2.061 (95% CI 1.545-2.749, p = 0.000) respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Hyperuricemia and acute kidney injury. a The pooled rates of AKI incidence in control and hyperuricemia (HUA) group; (b) Subgroup analysis in all hospitalized patients and patients with cardiac surgery and PCI; (c) The pooled hospital mortality in control and HUA group; (d) The pooled levels of SUA in No-AKI and AKI group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Fig. 3.

Effects of hyperuricemia on incidence of acute kidney injury

Fig. 4.

Pooled odds ratios of serum uric acid to predict acute kidney injury

Subgroup analysis

Although the pooled rates of AKI incidence after cardiac surgery in hyperuricemia and control group were 34.3% (95% CI 4.4-85.5%) and 29.7% (95% CI 4.6-78.7%) respectively (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.96-1.60, p = 0.10), the AKI incidence after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were 16.0% (95% CI 8.6-27.7%) and 5.3% (95% CI 2.5-10.9%) respectively (OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.93-5.45, p < 0.00001) (Figs. 2b and 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of hyperuricemia on incidence of acute kidney injury in all and subgroup analysis

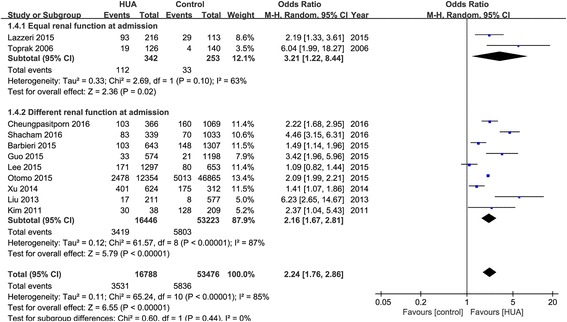

We also conducted subgroup analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies (Fig. 6). The pooled ORs of hyperuricemia on AKI were 2.87 (95% CI 1.43-5.76) and 2.11 (95% CI 1.63-2.75) respectively. In addition, to reduce the bias of included patients, we also analyzed studies with or without equal renal function, which was defined as serum creatintine or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) without significant different at admission between hyperuricemia and control groups. There were significant differences in renal function at admission between hyperuricemia and control groups in most of the included studies, while only two studies with equal renal function were included, and the pooled OR was 3.21 (95% CI 1.22-8.44, p = 0.02) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Effects of hyperuricemia on incidence of acute kidney injury in prospective and retrospective studies

Fig. 7.

Effects of hyperuricemia on incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with or without equal renal function at admission

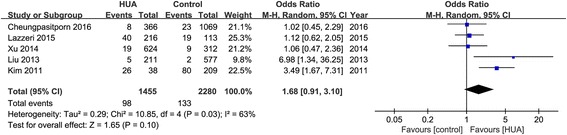

Effects of SUA on hospital mortality

Five studies with 3735 patients provided the hospital mortality. The pooled rates of hospital mortality in hyperuricemia group and control group were 8.9% (95% CI, 2.1-30.8%) and 5.0% (95% CI, 1.0-21.9%) respectively (OR 1.68, 95% CI 0.91-3.1, p = 0.083) (Figs. 2c and 8). The relationship between hyperuricemia and hospital mortality was not significant.

Fig. 8.

Effects of hyperuricemia on hospital mortality

SUA levels in AKI and Non-AKI groups

Five studies assessed the SUA levels in AKI and Non-AKI groups. The pooled pre-operative SUA levels were higher in AKI group (376.35 μmol/L, 95% CI 321.76-430.93 μmol/L) than in Non-AKI group (317.09 μmol/L, 95% CI 304.50-329.68 μmol/L) (Std diff in means 0.860, 95% CI 0.334-0.112, p = 0.010) (Fig. 2d).

Publication bias

The funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias. Egger’s test for a regression intercept gave a p-value of 0.696 for effects of hyperuricemia on incidence of AKI, indicating no publication bias.

Discussion

AKI is one of the most serious complications with a reported mortality rate of 15% in hospitalized patients [15]. Our meta-analysis showed that HUA is a critical and potential risk factor for the incidence of AKI, not only in preoperative patients as reported previously but also in all hospitalized patients.

In this meta-analysis, we found that the pooled rates of AKI incidence in hyperuricemia group were much higher than that in the control group. The underlying reasons were analyzed as follows. Firstly,majority of uric acid is excreted by the kidneys and accounts for 70%. It should be noted that approximately 90–95% of the filtered uric acid from glomerular is absorbed, mostly by proximal tubules [16, 17]. Secreted uric acid by the renal tubules is very little. Consequently the SUA concentration depends on glomerular filtration and subsequent tubular reabsorption function. There is mounting evidence to consider SUA as a clear marker for chronic kidney disease or an independent risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease [18, 19]. A number of studies demonstrated that pre-existing chronic kidney disease increases the risk of AKI. Ishani et al. reported that the incidence of AKI was 8.8% in patients with chronic kidney disease versus 2.3% in patients without chronic kidney disease [20]. Pannu N et al. found that the risk of AKI was 18-fold higher in patients with an eGFR less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 than in those with an eGFR more than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [21]. Therefore, patients with increased SUA may already have the subclinical chronic renal dysfunction, leading them to be more vulnerable to AKI. In addition, we did an adjustment for the important covariate baseline GFR or serum creatinine. Unfortunately, there were only two included studies with equal renal function at admission, the results from which was more convincing.

Seconding, an elevated SUA concentration has been found to be associated with damage of impartment organs and result to many diseases such as hypertension [17, 22], metabolic syndrome [23], atherosclerosis [24], myocardial infarction [25], diabetes mellitus [4], stroke [26] and so on. All of the above diseases are most common risk factor of AKI, which make it sense that the incidence of AKI in the hyperuricemic patients is higher than those in the normouricemic patients.

A number of studies supported that uric acid is an independent risk factor of cardiovascular disease. The incidence rate of cardiovascular disease in patients with hyperuricemia is higher than that in the normal population [27]. A meta-analysis showed that incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) in the hyperuricemic patients was 1.34 times (95% CI 1.19-1.49) than that in the normouricemic patients [5]. Patients with CHD combined with hyperuricemia have higher incidence of myocardial infarction. The global number of cardiac surgeries or PCI each year is approximately 2 million [28, 29] and one of the most common and serious post-operative complications is AKI. A current meta analysis found that the incidence of AKI after cardiac surgery was 22.3% around the world (95% CI 19.8-25.1) [2]. The incidence of PCI-induced AKI has been estimated between 2% and 30% depending mainly on baseline renal function, which is increasing along with the higher prevalence of CHD year by year [15, 29]. Our results suggest that higher pre-PCI SUA increased risk of AKI. We speculated that the patients with increased SUA maybe undergo more PCI, consequently have more incidence of AKI. In addition, it was found contrast agents have a uricosuric effect through enhancing renal tubular secretion of uric acid [30], which may promote renal injury caused by possible nephrotoxic effect of uric acid. However, there are more complex risk factors and mechanisms of AKI incidence after cardiac surgery than PCI, which led to less difference of the pooled rate of AKI between hyperuricemia and control group. Moreover, there need more studies to confirm the prognostic role of SUA in AKI incidence after cardiac surgery.

Finally, it is well-known that AKI is resulted from multiple and interactive pathways. Uric acid itself can cause AKI due to several mechanisms ranging from direct tubular toxicity (crystal induced injury) [9] to indirect injury (secondary to vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, inflammatory and so on). In both animal and human models, uric acid is found to inhibit proliferation and migration of endothelial cell and cause dysfunction and apoptosis of endothelial cell [31, 32]. Animal experimental studies suggest that uric acid may cause renal vasoconstriction via inhibiting of renal nitric oxide synthase to reduce product of nitric oxide in endothelial cell [31] and via stimulating of the renin-angiotensin system [32]. Renal vasoconstriction is a common pathogenic factor in the progression of AKI [33]. Inflammatory and oxidative stress are two of important mechanisms of AKI [34]. Experimentally, it has been found that uric acid activates inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway [35]. Increasing SUA also stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory systemic cytokine i.e. tumor necrosis factor α [36], and the local chemokines, i.e. monocyte chemotactic protein 1 in the kidney [37]. High SUA levels induced oxidative damage of proximal tubule cell by activating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase [38]. Therefore, SUA may be involved in the progress of AKI and contribute to higher incidence of AKI in the patients with hyperuricemia. Regardless of whether elevated SUA is solely a predictive factor of AKI or an independent risk factor of AKI, careful attention is warranted.

Thus, we wonder if uric acid lowering therapy could decrease the risk for developing AKI. At present, no trials showed that lowering SUA may provide benefit in preventing AKI. Allopurinol was once used in the hyperuricemic patients before cardiovascular surgery to reduce oxidative stress and then improve cardiovascular outcomes [39]. However, it was found that allopurinol couldn’t prevent the incidence of AKI after cardiac surgery in these studies [40]. After that, researchers confirmed the protective role of allopurinol in the renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats [41, 42]. In addition, in the cisplatin-induced AKI models, the uric acid lowering drugs rasburicase [43] and febuxostat [44] could attenuate renal injury by their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects. A prospective, randomized pilot trial with 26 cardiac surgery patients with hyperuricemia showed that there was no significant difference of postoperative serum creatinine between subjects receiving rasburicase and the control group. However, urine NGAL tended to be lower in the rasburicase group, which suggested that lowing uric acid before surgery might protect against renal tubular injury [45]. In Sezai A et al. study, febuxostat had a renoprotective effect with a significant earlier decrease of UA after cardiac surgery in hyperuricemic patients compared with allopurinol [46]. Therefore, we postulated that early intervention to decrease SUA levels may lower the risk of developing AKI.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically evaluate the indicated effect of SUA on the incidence of AKI especially after cardiac surgery and PCI. It included data more than 75,000 patients from 18 studies. We analyzed these studies in detail considering the effect of renal function at admission and study design.

However, the present study may have limitations. Firstly, if there were more randomized controlled trials with high quality and large samples in this meta-analysis, these results would be more convincing. Secondly, Kanda et al. indicated that SUA level has a U-shaped association with loss of kidney function and low SUA (male <5 mg/dl; female <3.6 mg/dl) is also a candidate predictor of chronic kidney disease [47]. We are only focused on the role of hyperuricemia in AKI without referring hypouricemia which will need more studies in the future.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrated that elevated SUA levels could be associated with an increased risk of developing AKI especially in the patients after cardiac surgery and PCI.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Kidney Disease and Blood Purification, Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (14DZ2260200). The funding was used for analysis and interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

Pubmed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, OVID and EMBASE databases were used to identify all relevant published articles for review. These articles are open to the public.

Authors’ contribution

XXL planned the study, searched the literature, assessed studies, extracted data, analyzed data and prepared the article. HJC searched the literature, assessed studies, extracted data, analyzed data and assisted in article preparation. SNN and CRY assisted in the data analysis. ZT assisted with the statistical analysis and editing of the manuscript. DXQ assisted in article review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- SUA

Serum uric acid

Contributor Information

Xialian Xu, Email: xu.xialian@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Jiachang Hu, Email: hjc0503@163.com.

Nana Song, Email: song.nana@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Rongyi Chen, Email: chenry825@hotmail.com.

Ting Zhang, Email: 14111210028@fudan.edu.cn.

Xiaoqiang Ding, Phone: +86-021-64041990-2138, Email: ding.xiaoqiang@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

References

- 1.Fang Y, Ding X, Zhong Y, Zou J, Teng J, Tang Y, Lin J, Lin P. Acute kidney injury in a Chinese hospitalized population. Blood Purif. 2010;30(2):120–126. doi: 10.1159/000319972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu J, Chen R, Liu S, Yu X, Zou J, Ding X. Global Incidence and Outcomes of Adult Patients With Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(1):82–89. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RJ, Segal MS, Srinivas T, Ejaz A, Mu W, Roncal C, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Gersch M, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Kang DH, et al. Essential hypertension, progressive renal disease, and uric acid: a pathogenetic link? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):1909–1919. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lytvyn Y, Perkins BA, Cherney DZ. Uric acid as a biomarker and a therapeutic target in diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, Choi HK, Heitjan DF, Albert DA. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(2):170–180. doi: 10.1002/acr.20065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otomo K, Horino T, Miki T, Kataoka H, Hatakeyama Y, Matsumoto T, Hamada-Ode K, Shimamura Y, Ogata K, Inoue K, et al. Serum uric acid level as a risk factor for acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients: a retrospective database analysis using the integrated medical information system at Kochi Medical School hospital. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lee EH, Choi JH, Joung KW, Kim JY, Baek SH, Ji SM, Chin JH, Choi IC. Relationship between Serum Uric Acid Concentration and Acute Kidney Injury after Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(10):1509–1516. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.10.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbieri L, Verdoia M, Schaffer A, Cassetti E, Marino P, Suryapranata H, De Luca G, Novara Atherosclerosis Study G Uric acid levels and the risk of Contrast Induced Nephropathy in patients undergoing coronary angiography or PCI. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(2):181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roncal CA, Mu W, Croker B, Reungjui S, Ouyang X, Tabah-Fisch I, Johnson RJ, Ejaz AA. Effect of elevated serum uric acid on cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2007;292(1):F116–122. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garabed Eknoyan, Nathan W.Levin.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1-266. [PubMed]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfaraj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, Jaber BL, Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the American Society of N World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(9):1482–1493. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00710113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang Y, Teng J, Ding X. Acute kidney injury in China. Hemodial Int. 2015;19(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richette P, Bardin T. Gout. Lancet. 2010;375(9711):318–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Susic D, Frohlich ED. Hyperuricemia: A Biomarker of Renal Hemodynamic Impairment. Cardiorenal Med. 2015;5(3):175–182. doi: 10.1159/000381317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LYC, Zhao Y, Zeng X, Liu F, Fu P. Is hyperuricemia an independent risk factor for new-onset chronic kidney disease?: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on observational cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2014;27:15–122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feig DI. Uric acid: a novel mediator and marker of risk in chronic kidney disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(6):526–530. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328330d9d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishani A, Xue JL, Himmelfarb J, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Molitoris BA, Collins AJ. Acute kidney injury increases risk of ESRD among elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):223–228. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn BR, Dong J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S. Modification of outcomes after acute kidney injury by the presence of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):206–213. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe S, Kang DH, Feng L, Nakagawa T, Kanellis J, Lan H, Mazzali M, Johnson RJ. Uric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002;40(3):355–360. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000028589.66335.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billiet L, Doaty S, Katz JD, Velasquez MT. Review of hyperuricemia as new marker for metabolic syndrome. ISRN Rheumatol. 2014;2014:852954. doi: 10.1155/2014/852954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao G, Huang L, Song M, Song Y. Baseline serum uric acid level as a predictor of cardiovascular disease related mortality and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan L, Liu Z, Zhang C. Uric acid as a predictor of in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70(3):1597–1601. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanbay M, Segal M, Afsar B, Kang DH, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Johnson RJ. The role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of human cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2013;99(11):759–766. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okura T, Higaki J, Kurata M, Irita J, Miyoshi K, Yamazaki T, Hayashi D, Kohro T, Nagai R, Japanese Coronary Artery Disease Study I Elevated serum uric acid is an independent predictor for cardiovascular events in patients with severe coronary artery stenosis: subanalysis of the Japanese Coronary Artery Disease (JCAD) Study. Circ J. 2009;73(5):885–891. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Wang Z, Edelstein CL, Devarajan P, Patel UD, Zappitelli M, et al. Postoperative biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and poor outcomes after adult cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(9):1748–1757. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tehrani S, Laing C, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury following PCI. Eur J Clin Inv. 2013;43(5):483–490. doi: 10.1111/eci.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Postlethwaite AE, Kelley WN. Uricosuric effect of radiocontrast agents. A study in man of four commonly used preparations. Ann Intern Med. 1971;74(6):845–852. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-6-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khosla UM, Zharikov S, Finch JL, Nakagawa T, Roncal C, Mu W, Krotova K, Block ER, Prabhakar S, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2005;67(5):1739–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu MA, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ, Kang DH. Oxidative stress with an activation of the renin-angiotensin system in human vascular endothelial cells as a novel mechanism of uric acid-induced endothelial dysfunction. J Hypertens. 2010;28(6):1234–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haase M, Bellomo R, Devarajan P, Schlattmann P, Haase-Fielitz A. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in diagnosis and prognosis in acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(6):1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(11):4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y, Fang L, Jiang L, Wen P, Cao H, He W, Dai C, Yang J. Uric acid induces renal inflammation via activating tubular NF-kappaB signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Blok WL, Netea RT, van der Meer JW. The role of hyperuricemia in the increased cytokine production after lipopolysaccharide challenge in neutropenic mice. Blood. 1997;89(2):577–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang DH. A Role for Uric Acid in the Progression of Renal Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(12):2888–2897. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000034910.58454.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verzola D, Ratto E, Villaggio B, Parodi EL, Pontremoli R, Garibotto G, Viazzi F. Uric acid promotes apoptosis in human proximal tubule cells by oxidative stress and the activation of NADPH oxidase NOX 4. PLoS One. 2014;9(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simko LC, Walker JH. Preoperative antioxidant and allopurinol therapy for reducing reperfusion-induced injury in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. Crit Care Nurse. 1996;16(6):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ejaz AA, Mu W, Kang DH, Roncal C, Sautin YY, Henderson G, Tabah-Fisch I, Keller B, Beaver TM, Nakagawa T, et al. Could uric acid have a role in acute renal failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(1):16–21. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00350106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willgoss DA, Zhang B, Gobe GC, Kadkhodaee M, Endre ZH. Repetitive brief ischemia: intermittent reperfusion during ischemia ameliorates the extent of injury in the perfused kidney. Ren Fail. 2003;25(3):379–395. doi: 10.1081/JDI-120021164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhoden E, Teloken C, Lucas M, Rhoden C, Mauri M, Zettler C, Bello-Klein A, Barros E. Protective effect of allopurinol in the renal ischemia--reperfusion in uninephrectomized rats. Gen Pharmacol. 2000;35(4):189–193. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(01)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ejaz AA, Dass B, Kambhampati G, Ejaz NI, Maroz N, Dhatt GS, Arif AA, Faldu C, Lanaspa MA, Shah G, et al. Lowering serum uric acid to prevent acute kidney injury. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(6):796–799. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahmi AN, Shehatou GS, Shebl AM, Salem HA. Febuxostat exerts dose-dependent renoprotection in rats with cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2016;389(8):819–830. doi: 10.1007/s00210-016-1258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bose B, Badve SV, Hiremath SS, Boudville N, Brown FG, Cass A, de Zoysa JR, Fassett RG, Faull R, Harris DC, et al. Effects of uric acid-lowering therapy on renal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(2):406–413. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sezai A, Soma M, Nakata K, Hata M, Yoshitake I, Wakui S, Hata H, Shiono M. Comparison of febuxostat and allopurinol for hyperuricemia in cardiac surgery patients (NU-FLASH Trial) Circ J. 2013;77(8):2043–2049. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanda E, Muneyuki T, Kanno Y, Suwa K, Nakajima K. Uric acid level has a U-shaped association with loss of kidney function in healthy people: a prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shacham Y, Gal-Oz A, Flint N, Keren G, Arbel Y. Serum Uric Acid Levels and Renal Impairment among ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Intervention. Cardiorenal Med. 2016;6(3):191–197. doi: 10.1159/000444100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Harrison AM, Erickson SB. Admission hyperuricemia increases the risk of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(1):51–56. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang J, Zhang P, Hu X, Zhi L. Elevated serum uric acid after injury correlates with the early acute kidney in severe burns. Burns. 2015;41(8):1724–31. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lazzeri C, Valente S, Chiostri M, Gensini GF. Long-term prognostic role of uric acid in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and renal dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2015;16(11):790–94. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaipov A, Solak Y, Turkmen K, Toker A, Baysal AN, Cicekler H, Biyik Z, Erdur FM, Kilicaslan A, Anil M, et al. Serum uric acid may predict development of progressive acute kidney injury after open heart surgery. Ren Fail. 2015;37(1):96–102. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2014.976130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo W, Liu Y, Chen JY, Chen SQ, Li HL, Duan CY, Liu YH, Tan N. Hyperuricemia Is an Independent Predictor of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Angiology. 2015;66(8):721–26. doi: 10.1177/0003319714568516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joung KW, Jo JY, Kim WJ, Choi DK, Chin JH, Lee EH, Choi IC. Association of preoperative uric acid and acute kidney injury following cardiovascular surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(6):1440–47. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J, Chen Y, Liang X, Hu P, Cai L, An S, Li Z, Shi W. Impact of pre-operative uric acid on acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery in elderly patients] Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2014;42(11):922–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Tan N, Chen J, Zhou Y, Chen L, Chen S, Chen Z, Li L. The relationship between hyperuricemia and the risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with relatively normal serum creatinine. Clin. 2013;68(1):19–25. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(01)OA04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lapsia V, Johnson RJ, Dass B, Shimada M, Kambhampati G, Ejaz NI, Arif AA, Ejaz AA. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for acute kidney injury. Am J Med. 2012;125(3):302 e309-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Ejaz AA, Kambhampati G, Ejaz NI, Dass B, Lapsia V, Arif AA, Asmar A, Shimada M, Alsabbagh MM, Aiyer R, et al. Post-operative serum uric acid and acute kidney injury. J Nephrol. 2012;25(4):497–505. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park S-H, Shin W-Y, Lee E-Y, Gil H-W, Lee S-W, Lee S-J, Jin D-K, Hong S-Y. The Impact of Hyperuricemia on In-Hospital Mortality and Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ J. 2011;75(3):692–97. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JH, Gil HW, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. Serum uric acid level as a marker for mortality and acute kidney injury in patients with acute paraquat intoxication. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(6):1846–52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ben-Dov IZ, Kark JD. Serum uric acid is a GFR-independent long-term predictor of acute and chronic renal insufficiency: the Jerusalem Lipid Research Clinic cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(8):2558–66. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toprak O, Cirit M, Esi E, Postaci N, Yesil M, Bayata S. Hyperuricemia as a risk factor for contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67(2):227–35. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Pubmed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, OVID and EMBASE databases were used to identify all relevant published articles for review. These articles are open to the public.