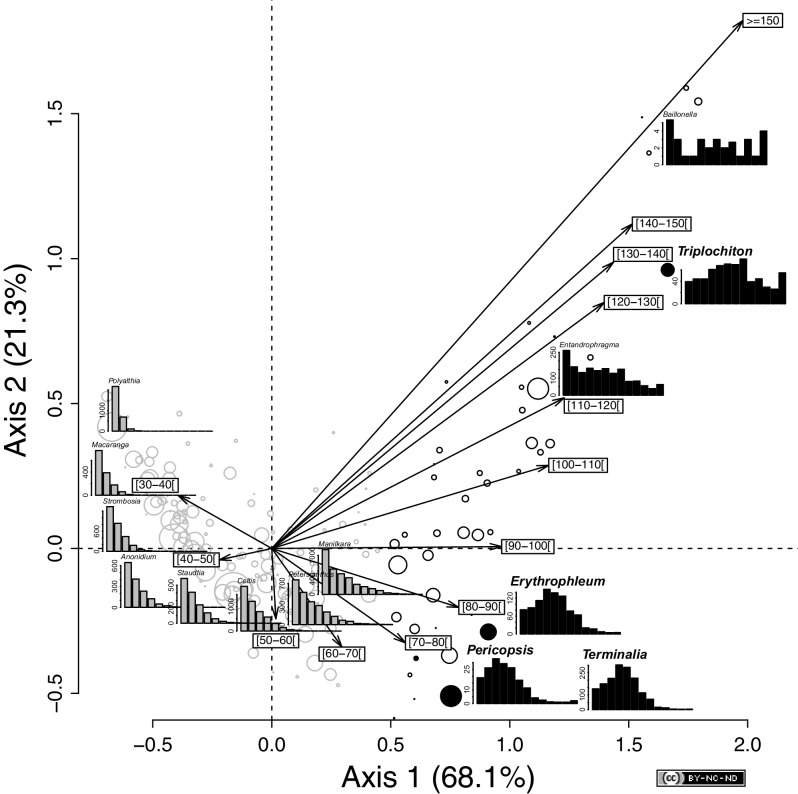

Figure 2. Variation in tree diameter distribution among the 176 genera across the SRI.

Projection of the genera and the 10-cm-wide diameter classes in the ordination space defined by the first two axes of a correspondence analysis of the abundance matrix, as defined by 176 genera and 13 diameter classes. The size of the circles is proportional to the square root of the genus abundance. The color of the symbol corresponds to the two groups identified with a clustering analysis (based on Euclidean distances and an average agglomeration method) on the species score on the first factorial axis. Genera that showed a reverse-J diameter distribution (n = 134) are indicated in gray and those genera that showed a deviation from the reverse-J distribution (n = 42) in black (e.g., Baillonella). Black filled circles indicate the four genera that are monospecific in the SRI and used for the age estimations. Diameter distribution of the 10 most abundant genera is shown in addition to that of the four selected genera: Celtis (gray), Polyalthia (gray), Strombosia (gray), Petersianthus (gray), Manilkara (gray), Entandrophragma (black), Terminalia (black), Anonidium (gray), Staudtia (gray), and Macaranga (gray). Statistics: R (https://www.r-project.org/), CAD: Illustrator CS4 (https://www.adobe.com).