Abstract

A novel synthetic approach to amido-quinones by the reaction of naphthoquinones with hydroxamic acids under basic conditions was developed. The reaction is mild and operationally simple, and it affords high yields of amido-quinones. With this new method, a novel highly strong HDAC6 inhibitor, which showed high toxicity to AML cells, was successfully synthesized.

Graphical Abstract

Amido-quinones are core structures of many biologically active natural products and synthetic molecules. Some of these compounds, such as Hygrocin A, and Salinisporamycin, exhibit very important anti-cancer and antibiotic activities (Scheme 1a).1a–1e Besides their biological applications, amido-quinones were also reported being used as metal-chelators in catalysis.1f Recently, a novel amido-quinone based HDAC6 selective inhibitor (NQN-1) was developed that showed selective toxicity toward AML (Acute Myeloid Leukemia) cells at micromole concentration.2 Up to date, mainly two methods are available to access such amido-quinone structures (Scheme 1b): (1) Amino-quinone is obtained by directly warming a mixture of quinones and NaN3 in AcOH, and the amino-quinone then reacting with acyl chloride in the presence of strong base forms the final amido-quinone product. The strong base, such as NaH, is indispensable in the acylation reaction because the amino group is highly deactivated by the quinone ring, and the generation of nitrogen anion with strong base is necessary to make the nucleophilic substitution reaction proceed. As a result, working with this corrosive and explosive NaN3/AcOH reaction system, as well as handling the susceptible acylation reaction, make this method considerably labor-intensive and time-consuming.3 (2) Amido-quinone is directly formed by oxidation of corresponding di-methoxy-N-phenyl amides with strong oxidant, such as hypervalent iodine compounds. This method can afford various amido-quinones with different substituents.4 However, the substrates that are susceptible to strong oxidants cannot tolerate this reaction condition. In this context, developing more concise and environment-benign synthetic methods to access these amido-quinone structures is highly desirable and of great significance.

Scheme 1.

Amido-quinone structures and the synthetic methods

There are many methods being reported to access aryl C-N bonds, and the most reliable ones are Buchwald-Hartwig amination, Ullman coupling reaction, and Chan-Lam coupling reaction.5 The advent of direct amination using hydroxylamine or its derivatives as amination reagent by N-O bond cleavage provides chemists with new powerful tools to create such C-N bonds, but these N-O bonds cleavage usually need the assistance of transition-metals.6 Recently, metal-free synthetic methods to access arylamines are attracting more and more attention.7 To our knowledge, March reported the first non-catalyzed direct amidation of aromatic compounds via N,O-bond cleavage with hydroxamic acid using poly phosphoric acid (PPA) as a solvent, but this method cannot be practically useful because of its extremely limited substrate scope, low yields and harsh conditions.8 In 2015, Wang et al reported a direct amidation method to access aminophenol compounds with N-hydroxyindolinones, which involved a regioselective [1,3]-arrangement.9 Very recently, Cheng and Li et al reported direct aminations of benzofuran-2(3H)-ones with hydroxylamine derivatives via a SET event, in which the two types of reactants were acting as electron-donors and electron-receptors, repectively.10 Despite these achievements, direct amidation of quinones has never been reported. As such, we envisioned the amide-quinone structure could be achieved by direct amidation of quinones under specific reaction conditions with hydroxamic acid or its derivatives. With our continuing interest in quinone-based organic molecules,2, 3c, 11 we report here a metal-free direct amidation of naphthoquinones with hydroxamic acids (Scheme 1c), and its application in the synthesis of a highly potent HDAC6 inhibitor.

Initially, we employed 1,4-naphthoquinone (1a) and N-hydroxybenzamide (2d) as starting materials to interrogate different reaction conditions (Table 1). To our great delight, the desired product (3ad) was obtained with 68% yield when the starting materials were treated with K2CO3 at 70 °C in 1,4-dioxane (entry 1). However, no desired product was found when 1a and 2d were stirred under the same reaction conditions but in absence of the base (entry 2). This indicated that the base is indispensable for the coupling reaction between 1a and 2d. Following the initial attempt, several other solvents were then screened for the reaction. It showed that CH3CN is the most suitable solvent, and 3ad was obtained with 75% yield when it was used as the solvent (entry 7), while THF, CH2Cl2, MeOH, and DMF offered 60%, 21%, 0%, and 72% yield of the desired product 3ad, respectively (entries 3–6). Besides K2CO3, other types of bases, including organic bases and inorganic bases, were carefully tested for the reaction. Finally, iPr2NEt was proved to be the most efficient base for the coupling reaction and 3ad was obtained with 87% yield (entry 8), while others, such as Et3N, pyridine etc., were also effective bases but with lower yields (entries 10–11). However, the reaction was messy when stronger organic base DBU was employed (entry 12). It also showed that 2 equivalents loading of iPr2NEt (based on the loading of 2d) is required for the best performance of the reaction, and the yield of 3ad was decreased when the loading amount of iPr2NEt was lowered (entry 9). The reaction was slightly less productive when performed at room temperature with 80% yield of the final product (entry 13). There is no difference when the reaction was performed under argon atmosphere (entry 14), which indicated that oxygen and moisture do not affect the reaction.

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvent | base (equiv) | t (°C) | yield (%)b |

| 1 | 1,4-dioxane | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | 68 |

| 2 | 1,4-dioxane | - | 70 | none |

| 3 | THF | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | 60 |

| 4 | CH2Cl2 | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | 21 |

| 5 | MeOH | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | none |

| 6 | DMF | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | 72 |

| 7 | CH3CN | K2CO3 (2.0) | 70 | 75 |

| 8 | CH3CN | iPr2NEt (2.0) | 70 | 87 |

| 9 | CH3CN | iPr2NEt (1.0) | 70 | 53 |

| 10 | CH3CN | Et3N (2.0) | 70 | 76 |

| 11 | CH3CN | Pyridine (2.0) | 70 | 69 |

| 12 | CH3CN | DBU (2.0) | 70 | messy |

| 13c | CH3CN | iPr2NEt (2.0) | 25 | 80 |

| 14d | CH3CN | iPr2NEt (2.0) | 70 | 86 |

Reactions were performed by warming a mixture of 1a (0.6 mmol), 2d (0.5 mmol) and base (1.0 mmol) in indicated solvent (4 mL) for 12 hours.

Isolated yield based on 2d.

Reaction was performed at room temperature.

Reaction was performed under argon.

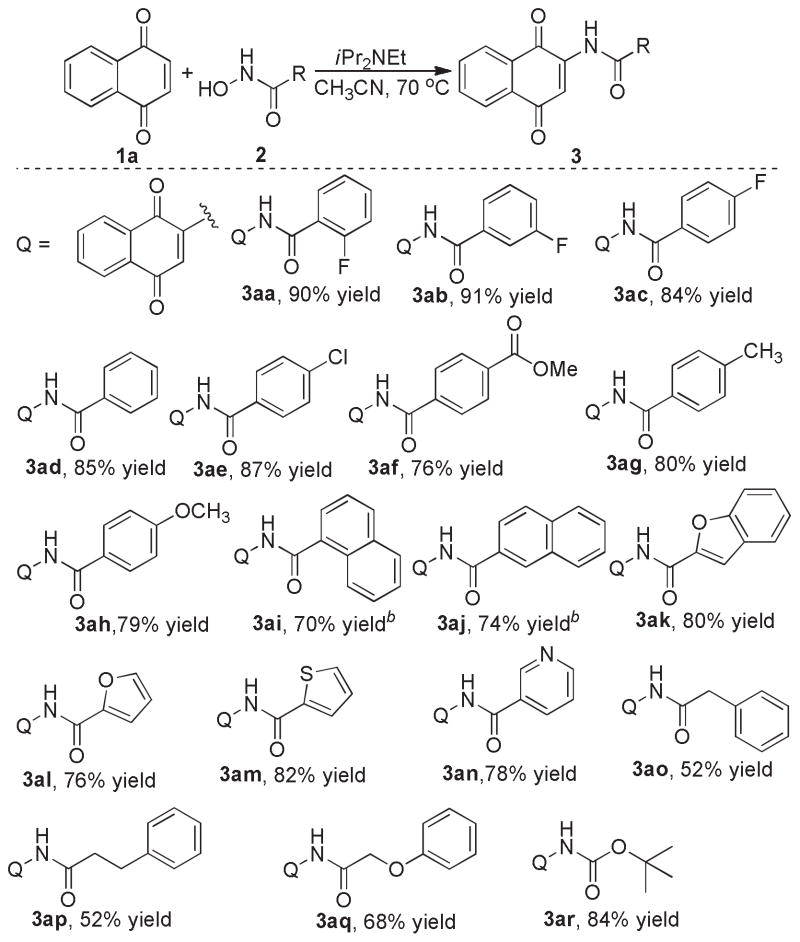

Subsequently, substrate scope of hydroxamic acids was explored with the most effective protocol (Scheme 2). As shown in Scheme 2, hydroxamic acids with substituents at different positions of phenyl rings do not affect the yields of their final products (3aa-3ac). Electron-withdrawing or electron-donating substituents at para-positions of phenyl rings of hydroxamic acids seemed to have little influence on the reactions, and the desired products were obtained with good yields (3ae-3ah). N-hydroxyl naphthamides have very poor solubility in CH3CN, but reactions went smoothly in DMF and gave slightly lower isolated yields of the final products (3ai-3aj). Hydroxamic acids with hetero-aromatic rings are also suitable substrates, and the corresponding products were obtained with good yields(3ak-3an). Alkyl hydroxamic acids are more challenging substrates, and the desired substrates were obtained with moderate yields(3ao-3aq). Notably, Boc-protected hydroxylamine can also be applied to the optimal reaction condition, and furnished the product with high yield (3ar).

Scheme 2. Substrate scope of hydroxamic acids.a.

aReactions were performed by warming a mixture of 1a (0.6 mmol), 2 (0.5 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (1.0 mmol) in CH3CN (4 mL) for 12 hours. bReactions were performed in DMF.

To further test the limitations of this reaction, the scope of various quinones was also investigated (Scheme 3). The results indicated that naphthoquinones with electron-deficient groups at the 2-position afford higher yields of the desired products (3cd-3dd), while naphthoquinones with electron-donating groups at the 2-position afford lower yields of the desired products (3ed-3fd, 3il). However, 2-chlorophenyl substituted 1,4-naphthoquinones at the 2-position gave extremely low yield of the corresponding product (3bd), probably because the steric hindrance hindered the formation of 3bd. Amido-substituted 1,4-naphthoquinone at the 2-position gave high yield of 3gd. Quinoline-5,8-dione is also a favorable substrate for this reaction, and afforded 79% yield of desired product 3hd. 6-Methyl-l,4-naphthoquinone gave high yields of amido-substituted products, but it was a 1:1 ratio of mixture of 2- and 3-substituted products, which is difficult to be purified (3jd). However, when 2-methyl naphthoquinone 1k, 1,4-benzoquinone 1l or 2,5-dimethyl-l,4-benzoquinone 1m were subjected to the standard conditions, no desired amido-quinone product was detected13.

Scheme 3. Substrate scope of quinone.a.

aReactions were performed by warming a mixture of 1 (0.6 mmol). 2d or 2l (0.5 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt(1.0 mol) in CH3CN (4 L) for 12 hours. bPyridine was used as the base.

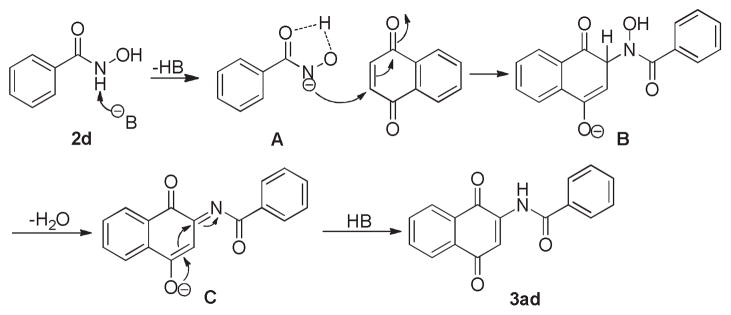

In order to probe the mechanism of the reaction, we carried out several controlled experiments as shown in Scheme 4. The model reaction proceeded well in the presence of excess amount of (2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-piperidin-l-yl)oxyl (TEMPO), which indicated the reaction was not going through a radical pathway (Scheme 4a). There was no reaction when 1,4- naphthoquinone was treated with N-methyl hydroxamic acid(Scheme 4b). However, the desired product was obtained with 78% yield when 1,4-naphthoquinone was treated with O-methyl hydroxamic acid (Scheme 4c). The results imply that the generation of amide anion is essential for the reaction. We also evaluated the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) for the reaction, and small KIE value was observed (Scheme 4d). This indicated that the reaction was not involving a direct C-H activation. We then proposed a plausible mechanism based on the results obtained. The reaction takes place via initial abstraction of H+ from compound 2d by base to form intermediate A, which then attack 1a via nucleophilic addition affording intermediate B. A molecule of water is abstracted from intermediate B forming intermediate C, and it then generates the final product 3ad after electrons rearrangement (Scheme 5).

Scheme 4.

Controlled experiments

Scheme 5.

Proposed mechanism

With great interest in amido-quinone based HDAC6 inhibitors, we have been endeavoring to synthesize compound 9, but were unsuccessful.13 With our new developed method of direct amidation of 1,4-naphthoquinones, however, compound 9 was obtained with 31% total yield (Scheme 6). Compound 1a and 7 were subjected to the optimal reaction conditions to yield compound 8, and deprotection of compound 8 in MeOH with catalytic amount of p-TsOH·H20 afforded compound 9. Biological studies for compound 9 showed that it has extremely high inhibition potency against human recombinant HDAC6 enzyme with IC50 of 6 nM, and it is stronger than SAHA (vorinostat), the first FDA approved HDAC inhibitor in the clinic, which has IC50 of 484 nM against HDAC6. Besides, western immunoblot showed that compound 9 induce hyper-acetylated tubulin because of HDAC6 inhibition. Up-regulation of Hsp70 suggests HDAC6 associated Hsp90 inhibition followed by the degradation of oncogenic protein FLT-3 and STAT5 in AML cells. In the end, compound 9 exhibited high toxicity to AML cells with EC50 of 367 nM compared to approximately 1 mM for SAHA, which indicated promising biological prospects.13

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the novel HDAC6 inhibitor by the newly developed direct amidation reaction of quinones.

In conclusion, we have developed a new metal-free method to construct biologically valuable amido-quinone structures by the direct reaction of quinones with hydroxamic acids under mild basic conditions, and it unveiled a new N-O bond cleavage reaction of hydroxamic acid. The new developed C-N bond formation reaction is convenient, operationally simple. and has broad substrates scope with high yields of final products (up to 91% yield). In particular, with this newly developed method, we have successfully synthesized a highly potent HDAC6 inhibitor (IC50 = 6 nM) that is hard to be accessed by usual methods, and the inhibitor exhibits promising biological activities, such as the high toxicity to AML cells (EC50 = 367 nM). Further biological studies are under way.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute (CA163452 to CJC), and Dept. of Drug Discovery and Biomedical Science SCCP Medical University of South Carolina. Support from College of Science (China Agricultural University ) was also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Synthesis of quinones 1, hydroxamic acids 2, experimental procedures for products 3, and 1H NMR, and 13C NMR spectra for 3 (PDF) were attached as Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

References

- 1.(a) Hadden MK, Lubbers DJ, Blagg BSJ. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1173. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Le Brazidec JY, Kamal A, Busch D, Thao L, Zhang L, Timony G, Grecko R, Trent K, Lough R, Salazar T, Khan S, Burrows F, Boehm MF. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3865. doi: 10.1021/jm0306125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cai P, Kong F, Ruppen ME, Glasier G, Carter GT. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1736. doi: 10.1021/np050272l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsuda S, Adachi K, Matsuo Y, Nukina M, Shizuri Y. J Antibiot. 2009;62:519. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang C, Wang M, Fan Z, Sun LP, Zhang A. J Org Chem. 2014;79:7626. doi: 10.1021/jo501419s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang M, Yang Y, Fan Z, Cheng Z, Zhu W, Zhang A. Chem Commun. 2015;51:3219. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09576f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inks ES, Josey BJ, Jesinkey SR, Chou CJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;7:331. doi: 10.1021/cb200134p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Fieser LF, Hartwell JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1935;57:1482. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lien J-C, Huang L-J, Wang J-P, Teng C-M, Lee K-H, Kuo S-C. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1996;44:1181. doi: 10.1248/cpb.44.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Josey BJ, Inks ES, Wen X, Chou CJ. J Med Chem. 2013;56:1007. doi: 10.1021/jm301485d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Nicolaou KC, Sugita K, Baran PS, Zhong YL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:207. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010105)40:1<207::AID-ANIE207>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Sugita K, Baran PS, Zhong YL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2221. doi: 10.1021/ja012125p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guram AS, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7901.Paul F, Patt J, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5969.Ma D, Cai Q, Zhang H. Org Lett. 2003;5:2453. doi: 10.1021/ol0346584.Jiao J, Zhang XR, Chang NH, Wang J, Wei JF, Shi XY, Chen ZG. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1180. doi: 10.1021/jo102169t.Chan DMT, Monaco KL, Wang RP, Winters MP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2933.Lam PYS, Clark CG, Saubern S, Adams J, Winters MP, Chan DMT, Combs A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2941.. For recent reviews, please see: Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6338. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800497.Hartwig JF. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1534. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p.Monnier F, Taillefer M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6954. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804497.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Chem Sci. 2011;2:27. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J.Rauws TRM, Maes BUW. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2463. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15236j.Beletskaya IP, Cheprakov AV. Organometallics. 2012;31:7753.Jiao J, Murakami K, Itami K. ACS Catal. 2016;6:610.

- 6.For some selected examples, please see: Matsuda N, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Org Lett. 2011;13:2860. doi: 10.1021/ol200855t.Yoo EJ, Ma S, Mei TS, Chan KSL, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7652. doi: 10.1021/ja202563w.Rucker RP, Whittaker AM, Dang H, Lalic G. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6571. doi: 10.1021/ja3023829.Chen Z-Y, Ye C-Q, Zhu H, Zeng X-P, Yuan J-J. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:4237. doi: 10.1002/chem.201400084.Ye C, Zhu H, Chen Z. J Org Chem. 2014;79:8900. doi: 10.1021/jo501544h.Zhu H, Chen P, Liu G. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:1766. doi: 10.1021/ja412023b.Ye Z, Dai M. Org Lett. 2015;17:2190. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00828.Yoon H, Lee Y. J Org Chem. 2015;80:10244. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01863.Zhou S, Yang Z, Chen X, Li Y, Zhang L, Fang H, Wang W, Zhu X, Wang S. J Org Chem. 2015;80:6323. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00767.Zhang Z, Yu Y, Liebeskind LS. Org Lett. 2008;10:3005. doi: 10.1021/ol8009682.

- 7.Kim HJ, Kim J, Cho SH, Chang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16382. doi: 10.1021/ja207296y.Kantak AA, Potavathri S, Barham RA, Romano KM, DeBoef B. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19960. doi: 10.1021/ja2087085.Antonchick AP, Samanta R, Kulikov K, Lategahn J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:8605. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102984.Samanta R, Bauer JO, Strohmann C, Antonchick AP. Org Lett. 2012;14:5518. doi: 10.1021/ol302607y.Manna S, Serebrenmkova PO, Utepova IA, Antonchick AP, Chupakhin ON. Org Lett. 2015;17:4588. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02320.Xiao Q, Tian L, Tan R, Xia Y, Qiu D, Zhang Y, Wang J. Org Lett. 2012;14:4230. doi: 10.1021/ol301912a.Mlynarski SN, Karns AS, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16449. doi: 10.1021/ja305448w.Zhu C, Li G, Ess DH, Falck JR, Kürti L. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18253. doi: 10.1021/ja309637r.. For a review, please see: Coeffard V, Moreau X, Thomassigny C, Greek C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:5684. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300382.

- 8.March J, Engenito JS. J Org Chem. 1981;46:4304. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Wang Q. Org Lett. 2015;17:6130. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C, Liu Y, Yang JD, Li YH, Li X, Cheng JP. Org Lett. 2016;18:1036. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, McClure J, Chou CJ. J Org Chem. 2015;80:4919. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ventura ON, Rama JB, Turi L, Dannenberg JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:5754. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For more information, please see Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.