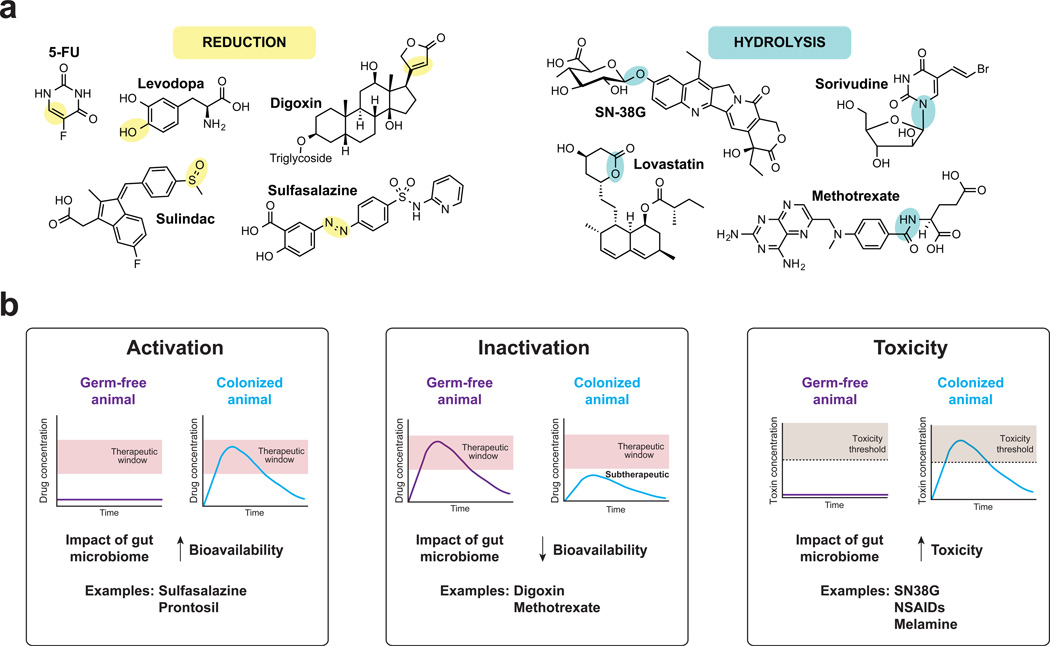

Figure 2. Major reaction types catalyzed by the gut microbiome and their pharmacological consequences.

A majority of known microbial biotransformations segregate into one of two reaction classes: reduction, in which compounds gain electrons from electron donors (part a), and hydrolysis, in which chemical bonds are cleaved through the addition of water (part b). The sites of modifications are highlight in yellow (reduction) and blue (hydrolysis). For a comprehensive list of drug biotransformations see Supplementary information S1 (Table). The microbial metabolism of pharmaceuticals can lead to their activation (part c), inactivation (part d) or result in the production of toxic compounds (part e); this is illustrated by the differential effects of the drugs in germ-free animals, compared to colonized animals. Activation refers to the conversion of a prodrug to its bioactive form, contributing to therapeutic concentrations. Examples include the prodrug sulfasalazine and prontosil. Inactivation refers to the conversion of an active metabolite to a downstream metabolite with reduced bioactivity. Examples include the cardiac drug digoxin and the anti-inflammatory drug methotrexate. Toxicity occurs due to the microbial production of metabolites that are toxic to the host. Examples include the hydrolysis of SN-38G to SN-38, the hydrolysis of glucuronidated NSAIDs to NSAIDs, and the metabolism of melamine to cyanuric acid.