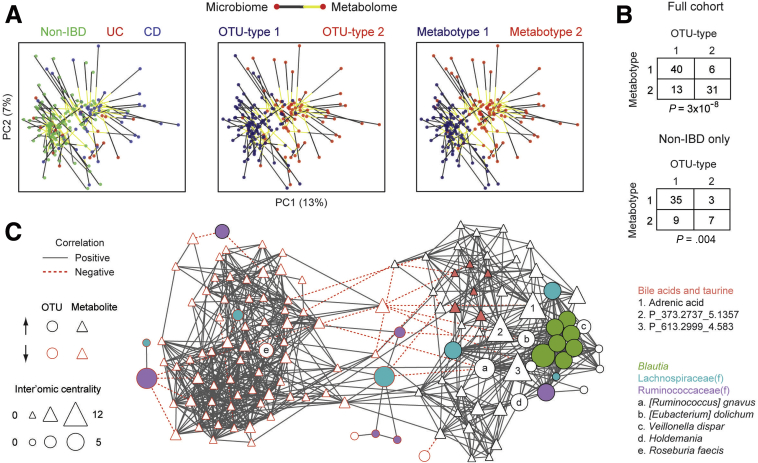

Figure 8.

Microbe–metabolite interactions between the IBD-associated microbial community type and metabotype. (A) The PCoA plot for the metabolome (visualized in Figure 6A) was rotated and rescaled using Procrustes, then superimposed on the PCoA plot for the microbiome (visualized in Figure 1A). Points represent 16S rRNA and UPLC/ToFMS data, color-coded by IBD status, OTU type, or metabotype. Each line connects the microbial and metabolomics data from one individual. (B) Contingency table of OTU type and metabotype for the full cohort and only non-IBD individuals. P values were calculated using the Fisher exact test. (C) An inter’omic network was constructed with nodes representing OTU-type–associated microbes and metabotype-associated spectral features with an importance score greater than 2 in random forest classifiers. Microbe (circle) and metabolite (triangle) nodes are outlined in red if they are decreased in OTU type 2 or metabotype 2, respectively. Node size reflects inter’omic degree centrality—the number of connections to nodes of the opposite data type (ie, microbe–metabolite pairs). Edges represent statistically significant correlations (q < 0.05) between microbe–microbe, metabolite–metabolite, or microbe–metabolite pairs. These correlations were made using residuals from multivariate DESeq2 models adjusting for sex, Jewish ancestry, current anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy, mode of delivery, family group, IBD diagnosis, and OTU type/metabotype. This approach highlights correlations that cannot be explained by these factors. Selected microbes and metabolites are indicated by fill color, numbers, or letters.