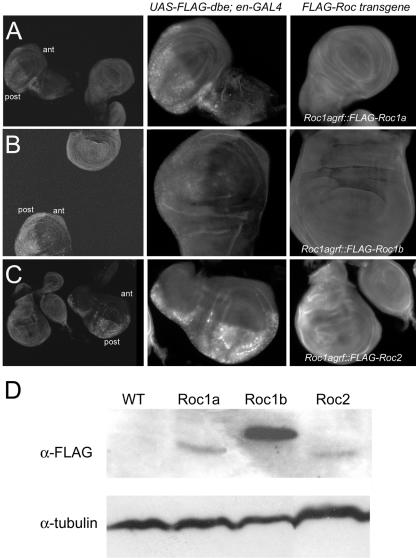

Figure 1.

Expression of Roc1agrf::FLAG-Roc transgenes. (A-C) Expression of FLAG-Roc proteins in the wing disc. Larvae from stocks expressing either FLAG-Roc1a (A), FLAG-Roc1b (B), or FLAG-Roc2 (C) from the Roc1a promoter were combined with UAS-FLAG-dribble; en-GAL4 larvae, dissected, fixed, and stained with an anti-FLAG antibody. Left, discs from both UAS-FLAG-dribble; en-GAL4 and Roc1agrf::FLAG-Roc genotypes in the same frame. Middle and right, close-ups of the same control (center) and experimental (right) discs, taken with same camera settings. Because it was difficult to discern background staining from the actual signal of the low, ubiquitous expression from the Roc1a promoter, UAS-FLAG-dribble; en-GAL4 discs served as both a positive and negative control for FLAG staining, because FLAG-Dribble is expressed only in the posterior compartment (post). Notice that the level of expression of each Roc protein is greater than that of the anterior compartments (ant) of the control discs where FLAG-Dribble is not expressed. (D) Western blot of embryo extracts showing expression of FLAG-Roc proteins. This level of FLAG-Roc1a expression is sufficient to rescue Roc1a mutant animals to adulthood. FLAG-Roc1b expression is significantly higher, but it is still unable to rescue the Roc1a mutation. Likewise, FLAG-Roc2 is expressed but also unable to rescue Roc1a mutants. Twice as much extract was loaded to the Roc2 lane. Similar results were observed from wing disc extracts (our unpublished data).