Abstract

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) can reduce the immune response by inhibiting CD8 T cell proliferation and cytotoxic activity. We studied a series of human viral (molloscum, human papillomavirus, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, smallpox) and bacterial infections (H pylori) for the in situ expression of PD L1, mononuclear cell infiltration, and CD8 activity and compared this to noninfectious idiopathic inflammatory conditions to better define which immune responses may be more highly correlated with an infectious agent. Each viral and bacterial infection showed increased PD-L1 expression that was most prominent in the mononuclear cell/CD8+ infiltrate surrounding the infection. However, the CD8 cells were mostly quiescent as evidenced by the low Ki67 index and minimal granzyme expression. Using a melanoma mouse model, acute reovirus infection increased PD L1 expression, but decreased CD8 cytotoxic activity and Treg (FOXP3) cell numbers. In comparison, idiopathic noninfectious chronic inflammatory processes including lichen sclerosis, eczema, Sjogren’s disease, and ulcerative colitis showed a comparable strong PD L1 expression in the mononuclear cell infiltrates but much greater Treg infiltration. However, this strong immunosuppressor profile was ineffective as evidenced by strong CD8 proliferation and granzyme expression. This data suggests that viral and bacterial infections induce a PD L1 response that, unlike noninfectious chronic inflammatory conditions, dampens the activity of the recruited CD8 cells which, in turn, may enhance the ability of anti-PD L1 therapy to eliminate the infectious agent.

Keywords: infectious, PD L1, autoimmune, checkpoint inhibition

INTRODUCTION

The human immune system is a complex inter-competing network designed to preserve the careful balance of eliminating foreign antigens while preventing excessive tissue damage. Essential to maintaining this balance are CTLA-4 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). The latter has been much more extensively studied and, after binding to PD-1 and other proteins, can suppress the immune system by reducing cytotoxic T cell CD8+ proliferation and activation (1–6). It has been well established that in infections due to a variety of viruses in humans and animals PD-L1 levels are inversely correlated with both viral load and CD8 proliferation and cytotoxic behavior (7–11). Importantly, anti-PD L1 treatment can enhance viral clearance that, in turn, is correlated with increased CD8 cytotoxic activity (7–9). Another key factor in balancing the activity of the immune system is the regulatory T (Treg) cell, marked by the protein FoxP3, which is involved in maintaining tolerance to self-antigens, preventing autoimmune disease, and in curtailing the immune system after an infectious agent is eliminated (12–15).

In non-infectious chronic inflammatory diseases which are purported to involve auto-antigens it is clear that PD L1, CD8 activation, and Tregs may play a role in the disease state. For example, in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease, increasing PD-L1 levels diminishes the severity of colitis (16). Ulcerative colitis in humans is associated with an increase in FOXP3+ T regs (13,17). In comparison, in the normal aging immune system, the loss of FOXP3+ Tregs has been associated with chronic inflammation in the elderly (14).

Many viruses can be associated with chronic inflammation in humans. Such viruses include human papillomavirus (HPV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and the molloscum virus. Viral DNA and specific RNA (ORFs) are typically made in high copy number in the more common forms of the diseases due to these viruses. Bacterial infections also can induce chronic inflammation where lymphocyte infiltration may be marked; a common example is the gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori. CD8 cells, as expected, have been shown to be a major cell recruited with these infections and have also been documented to play a key role in the non-infectious autoimmune diseases which include many diseases in humans such as eczema, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, ulcerative colitis, and Sjogren’s disease (18–20). The purpose of this manuscript is to compare the modulation of the immune system in a variety of infectious diseases and non-infectious chronic inflammatory diseases in humans by studying the immunosuppressors PD L1 and Tregs, the immune cell mediators including activated macrophages, NK cells, and CD8 cells, and activation of the CD8 cells as measured by granzyme expression and the Ki67 proliferation index. In this way, we hoped to elucidate if any features of the immune response may be strongly correlated with and thus specific for infectious agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

Paraffin embedded, formalin fixed de-identified biopsies were available from the files of Phylogeny (Powell, Ohio), Enzo Clinical Laboratory (Farmingdale, NY) and the files of one of us (GJN). Clinical information included the histology diagnosis, patient age/gender, and history of immunosuppression. We examined PD L1 expression in a total of 251 biopsies that included 191 histologically normal tissues from twelve distinct sites, 37 biopsies with viral infections (molloscum contagiosum, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the vulva, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the vulva, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), reovirus, and smallpox), 3 biopsies with bacterial infections (each Helicobacter pylori of the stomach), and 20 biopsies with idiopathic chronic inflammatory conditions (eczema and lichen sclerosus of the vulva, ulcerative colitis and Sjogren’s disease).

In situ hybridization

Our in situ hybridization method has been previously published protocol (21, 22). In brief, several serial sections were placed on silane coated slides, the paraffin removed, and the tissue pretreated with protease for 4 minutes at room temperature. The presence of either HPV, HSV, CMV, or EBV DNA was determined using the PathoGene Alkaline Phosphatase NBT/BCIP in situ assay for tissue sections (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). The negative and positive controls were provided by the manufacturer and gave the expected results. Reoviral RNA in situ hybridization was done with a previously published protocol that utilizes a 5’ digoxigenin tagged set of two LNA oligoprobes in which the detection system uses an antibody against digoxigenin that is conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (21).

Immunohistochemistry

Our immunohistochemistry protocol has been previously published (21, 22). In brief, after using a standard optimization protocol that included positive controls known to have the target of interest, we tested the tissues for the following antigens: CD8, CD45, CD68, Ki67 (each from Ventana Medical System), PD L1, FOXP3, CD117 (each from ABCAM) and granzyme (Enzo Life Scienes). For the mouse studies we used antibodies that could react against the mouse epitope for CD3, PD L1, FOXP3, CD117, IL22 (each from ABCAM) and granzyme (Enzo Life Sciences).

Co-expression analysis

Co-expression analyses were done using the Nuance system (CRI) as previously published (21, 22). In brief, a given tissue was tested for two different antigens using fast red as the chromogen for one target followed by immunohistochemistry using DAB (brown) as the second chromogen with hematoxylin as the counterstain. The results were then analyzed by the Nuance and InForm systems in which each chromogenic signal is separated, converted to a fluorescence based signal, then mixed to determine what percentage of cells were expressing the two proteins of interest.

Reovirus melanoma model and cell cultures

The protocol used with the C57BL/6 mice and the B16 melanomas were as previously described (23). In brief, the procedures were approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 105 B16 murine melanoma cells. Wild-type Reovirus type 3 (Dearing strain) is a unique isolate acquired from Oncolytics Biotech (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Reovirus was administered intravenously at 108 TCID50 per injection. Paclitaxel (Mayo Clinic Pharmacy, Rochester, MN) was injected intraperitoneally at 10 mg/kg per injection. Bidimensional tumor diameters were measured thrice-weekly using calipers and mice were killed when actively progressing tumors exceeded 1.0 cm. Different sets of mice were treated either with PBS, reovirus alone, reovirus plus sunintib, and reovirus plus paclitaxel (23).

We also tested various multiple myeloma cell lines that show a marked range in their susceptibility to reovirus infection. Cell cultures on the myeloma cell lines RPMI and U266 (each highly sensitive to reoviral infection), and OPM2 plus KM518 cells (each low sensitivity to reovirus infection) were done as previously reported (submitted for publication).

RESULTS

PD-L1 is not expressed in most normal tissues

To determine baseline expression, we did immunohistochemistry for PD-L1 in 191 normal tissues from twelve different sites. These were histologically normal tissues from people with no evidence of cancer. Table 1 has a compilation of this data. Note that no PD L1 expression was evident at nine of the sites. However, PD-L1 was highly expressed in each placenta (n=16), skin sample (n=12), and normal gastric biopsy (n=6) that was examined. Representative images are presented in Figure 1. Note that in each case the PD L1 is being expressed in cells that contain cytokeratin including trophoblasts, epidermal squamous cells, and glandular cells of the stomach. Figure 1 also highlights the lack of FOXP3 expression and mononuclear cell activation in these histologically normal tissues.

Table 1.

Compilation of PD L1 expression in normal tissues

| TISSUE (n = 191) | PD L1 | Target cell |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 0/6 | not applicable |

| Cervix | 0/44 | not applicable |

| CNS | 0/12 | not applicable |

| Colon | 0/12 | not applicable |

| Endometrium | 0/13 | not applicable |

| Esophagus | 0/12 | not applicable |

| Kidney | 0/15 | not applicable |

| Liver | 0/37 | not applicable |

| Lung | 0/6 | not applicable |

| Placenta | 16/16 | Trophoblasts |

| Skin | 12/12 | Squamous cells |

| Stomach | 6/6 | Glandular cells |

Figure 1. Expression of PD L1 and immune system modulators in normal tissues.

No detectable PD L1 was evident in most of the histologically normal tissues studied (panel A, normal colon). Similarly, rare T reg mononuclear cells are seen in the lamina propria of the normal colon (panel B, FOXP3) and Ki67 protein localizes to scattered clusters of epithelial cells, and not to the mononuclear cells (panel C). PD L1 was strongly expressed by the trophoblasts of the term placenta (panel D) and to the more superficial epithelial cells (arrow) of the gastric mucosa (panel E). Panel F shows the strong cytoplasmic signal for PD L1 in the epithelia and accessory structures (hair follicle, arrow) of the skin.

Immune response intensity is variable in the human infections

After establishing the baseline amount of PD L1 expression in the normal tissues, we then studied a variety of viral and bacterial infections in humans. As seen in Table 2, we studied 40 tissues that contained an infectious agent as documented by cytologic changes (molloscum contagiosum), in situ hybridization (HPV, CMV, EBV, smallpox virus, HSV) or the Giemsa stain (Helicobacter pylori). Table 2 shows that the inflammatory cell infiltrates in these infectious diseases varied from minimal (1+) to marked (3+). Thus, it is not surprising that the numbers of CD8, CD68, and NK cells also varied a great deal among the different infectious processes. These infectious diseases shared in common three findings: PD L1 up regulation, minimal Treg infiltration, and CD8 cell quiescence despite their large numbers in many of the infected tissues. PD L1 up regulation was mostly due to the mononuclear cells infiltrating the infected tissue and, thus, its intensity closely paralleled the numbers of CD8 cells. Co-expression analysis showed that most of the PD L1+ mononuclear cells were CD8+ with lesser numbers positive for CD68+ (see Figure 4).

Table 2.

Compilation of immune response to infectious agents.

| Category Infectious agent |

Inflammatory* cell infiltrate |

Immune Suppression PD L1 |

Immune Suppression FOXP3 |

CD8+ cells | CD8 activation** |

CD68 + cells | NK cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molloscum (n=9) | 1+ | 1+ | 0 | 1+ | minimal | 1+ | 1+ |

| HPV warts (n=9) | 1+ | 1+ | 0 | 1+ | minimal | 1+ | 1+ |

| Herpes simplex virus (n=3) | 3+ | 3+ | 1+ | 3+ | minimal | 3+ | 3+ |

| CMV (n = 3) | 3+ | 3+ | 0 | 3+ | minimal | 3+ | 3+ |

| EBV OHL*** (n=3) | 1+ | 1+ | 0 | 1+ | minimal | 1+ | 1+ |

| Helicobacter pylori (n=3) | 3+ | 3+ | 0 | 3+ | minimal | 3+ | 3+ |

| Smallpox (n=1) | 3+ | 3+ | Not done | 3+ | Not done | 3+ | Not done |

| Reovirus (n=9) | 2+ | 3+ | 0 | 2+ | minimal | 2+ | 2+ |

Inflammatory cell infiltrates, PD L1, FOXP3, CD8, CD68, and NK (CD117 and IL22) positive cells were scored as 0, 1+ (mean less than 10+ cells/200× field over the entire area of infected tissue), 2+ (mean score of 11 to 25+ cell/200× field) and 3+ (mean more than 25+ cells/200× field.

CD8 activation was scored as minimal (weak to no granyzme expression and/or less than 10% of the mononuclear cells + for Ki67) or strong (moderate to strong granzyme expression and/or more than 10% of the mononuclear cells positive for Ki67).

OHL = oral hairy leukoplakia - this was the only infectious disease studied in immunosuppressed patients (HIV-1 +).

Figure 4. Comparison of immune modulation between infectious and noninfectious chronic inflammatory conditions of the vulva.

Panels A–F show representative data for the immune infiltrates in eczema; the large arrow depicts epithelia and the small arrow stroma. Note the strong CD45+ lymphocytic infiltration that contains many CD8+ cells (panels A and B) and the strong PD L1 response that is primarily in the stromal mononuclear cells (panel C). The insert shows the fluorescent yellow signal that indicates that most of the PD L1 + cells also express CD8. The mononuclear cells include activated macrophages (CD68, panel D), Tregs (FOXP3, panel E; the insert shows the the FOXP3+ cells do not co-express PD L1) and stromal NK cells (CD 117, panel F). In comparison, the molloscum contagiosum virus elicts a weak lymphocytic response in the vulva (CD8, panel G) as does HPV 6 (hematoxylin and eosin, panel H) despite the high viral load (copy number I, in situ for HPV 6 DNA). Note that in comparison to the infiltrate in eczema the CD68 (panel J, arrow shows rare + cells in epidermis), Treg (FOXP3, panel K) and NK response in the stroma is weak (panel L).

Figure 2 shows representative examples of the PD L1/CD8 results. Note the many viral inclusions in the molloscum infection (panels A, B), and high EBV DNA copy number (panels C,D) where the inflammatory cell infiltrates were minimal. The PD L1 expression was invariably high in the infections with marked inflammatory cell infiltrate as seen in smallpox infection of the skin (panel E) and H pylori infection of the stomach (panel G). As expected, many of the mononuclear cells were CD8+ (panel F) but they showed minimal activation as evidenced by low granzyme expression and a low Ki67 index (panel H).

Figure 2. Expression of PD L1 and immune modulators in infected tissues.

The molloscum contagiosum virus form large viral-packed inclusions (panels A and B, large arrows) but it induces little of an immune response (small arrow). Note the strong PD L1 expression in the epithelia that lack the viral inclusions and in the endothelial cells. EBV DNA is present in high copy number in oral hairy leukoplakia (panel C, arrow) and does induce a strong PD L1 response in the epithelial cells (panel D) but only a weak inflammatory cell response. In comparison, the smallpox virus which produces large fluid filled vesicles that contain the multinucleate epithelial cells (large arrow, panel E) induces a strong inflammatory cell response at the epidermal/dermal interface (small arrow) that contains an intense PD L1 signal amongst many CD8+ cells (panels E and F). Helicobacter pylori induces an intense mononuclear cell infiltrate that is strongly positive for PD L1 (panel G) with a concomitant loss of the epithelial based signal. The PD L1 may be effective in modulating the CD8 response since, despite the large number of CD8 cells in this area (not shown), their Ki67 index is very low (panel H).

Reoviral infection of malignant cells including in the B16/C57BL/6 mouse model

The data above suggested that infectious agents could up-regulate PD L1 expression. Reovirus is a double stranded RNA virus with a strong propensity to infect human cancer cells and not the adjoining benign cells; the virus can easily be grown in cell culture (21, 23). Thus, we studied the PD L1 response after reovirus infection in both susceptible cell lines and in the B16 melanoma mice model where we also studied the immune response.

The myeloma cell lines offered a straightforward way to examine the effect of reoviral infection on PD L1 expression since the different lines varied a great deal in their sensitivity to the virus. The myeloma cell lines RPMI and U266 (reovirus sensitive) showed no productive reoviral infection 24 hours after inoculation but about 20% of the cells do show ample reoviral protein 48 hours after infection. PD L1 expression closely mirrored the reoviral protein results in these cells with similar numbers of cells expressing both reoviral protein and PD L1 (Figure 3). Also, co-expression experiments showed that PD L1 expression in the myeloma cells was limited to those with productive reoviral infection (Figure 3). Ammonia treatment that eliminates reovirus infection in these cells also eliminated the PD L1 expression(Figure 3). We found no increased PD L1 expression with reovirus exposure in the reovirus resistant OPM2 plus KM518 cell lines (data not shown).

Figure 3. Correlation of PD L1 expression and CD8 activity in reovirus infected cell lines and in C57BL/6 mice treated with B16 melanoma.

The melanoma cells grew rapidly in the mice and showed little PD L1 expression (panel A). Serial sections showed strong granzyme expression (panel B) and many FOXP3 positive cells (panel C1, arrows). Mice treated with reovirus showed a strong perivascular localization of reoviral RNA (not shown) which was paralleled by strong PD L1 expression (panel D). The reoviral proliferation was also associated with the marked reduction of granyzme expression (panel E) and the loss of Tregs (panel C2). Similarly, human infections, such as herpes simplex virus of the vulva (panel F) showed many CD8 cells that were not expressing granzyme (panel F) or Ki 67 (not shown); the arrow highlights a multinucleate HSV infected squamous cell. The myeloma cell line RPMI is susceptible to reovirus infection. The RPMI cells do not express PD L1 (panel G). However, 48 hours after infection reoviral protein is evident in many of the RPMI cells which now express PD L1 (panel H). The infection can be abrogated if ammonia (NH4) is added with the reovirus; under these conditions PD L1 is no longer evident (panel I). Co-expression analysis in these cells of reovirus (panel J, fluorescent red) and PD L1 (panel K, fluorescent green) demonstrate that it is the reoviral infected cells that express PD L1 (panel L, merged image, fluorescent yellow marks co-localization).

We next compared the T cell infiltrate (defined by CD3 expression), numbers of NK cells (defined by co-expression of CD 117 and IL22), Treg cells (defined by FOXP3 expression), PD L1 expression, CD8 activation (as measured by granzyme expression) and IL6 expression in the melanoma samples as a function of no treatment, reovirus treatment alone, or reovirus treatment plus either sunitinib or paclitaxel in the B16 mouse melanoma model. We had previously showed that reovirus in combination with either sunitinib or paclitaxel induced a productive reoviral infection in the B16 tumors that showed a striking perivascular distribution (23). The data are compiled in Table 3. Note that reoviral infection, when evidenced by viral RNA proliferation alone (nonproductive infection) or reoviral infection with ample capsid production (productive viral infection) was associated with increased perivascular T cell and NK cell infiltrates and increased PD L1 expression. Interestingly, reoviral infection per se (nonproductive or productive infection) also much diminished the Treg infiltration and the CD8 activation. The NK cell infiltrate were more strongly correlated with productive reoviral infection, as was IL6 expression, as each were maximized by reovirus in conjunction with either sunitinib or paclitaxel.

Table 3.

Compilation of reovirus induced molecular changes in the B16 mouse melanoma model

| Category | T cell infiltrate* | Immune Suppression PD L1 |

Immune Suppression FOXP3 |

CD8 activation (granzyme expression)** |

NK cells | IL6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No reovirus (n=3) BASELINE | 2+ | 1+ | 2+ | strong+ | 1+ | 1+ |

| Nonproductive reoviral infection***(n=3) | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ | minimal | 2+ | 1+ |

| Productive reoviral infection*** (n=6) | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ | minimal | 3+ | 3+ |

T cell infiltrates (CD3), PD L1, FOXP3, NK (CD117 and IL22) and IL6 positive cells were scored as 0, 1+ (mean less than 10+ cells/200× field over the entire area of infected tissue), 2+ (mean score of 11 to 25+ cell/200× field) and 3+ (mean more than 25+ cells/200× field

CD8 activation was scored as minimal (weak to no granyzme expression) or strong (moderate to strong granzyme expression).

Nonproductive reoviral infection, defined by the detection of reoviral RNA but not reoviral protein in the cancer cells, was seen in the three mice treated with reovirus alone.

Productive reoviral infection, defined by the detection of reoviral RNA and reoviral protein in the cancer cells, was seen in the six mice treated with reovirus plus sunitinib (3) or paclitaxel (3).

Figure 3 shows representative data for the reovirus experiments. Note that PD L1 expression is much increased after reoviral treatment (panel D vs A) and that there is a concomitant marked reduction in granzyme expression (panel E vs B) and FOXP3 Treg infiltration (panel C1 vs C2). Panel F shows the equivalent loss of CD8 activation in herpes simplex infection of the skin.

Non-infectious chronic inflammatory conditions elicit a strong immune response with CD8 activation despite ample PD L1 expression and Treg infiltration

Having observed that the immune response in viral and bacterial infections was characterized in many cases by increased number of CD8, CD68, and NK cells with concomitant PD L1 expression, low Treg numbers, and muted CD8 activity, we wanted to compare this to the immune response to non-infectious chronic inflammatory conditions. We studied lichen sclerosus, eczema, ulcerative colitis, and Sjogren's disease. The results are summarized in Table 4. Note that the noninfectious chronic inflammatory conditions, like many of the infectious diseases, showed an intense PD L1 response. Also, they each showed marked increases in the CD8+ cells together with many CD68+ and NK cells. However, unlike the infectious diseases, the non-infectious conditions each showed a striking increase in the Tregs. Further, despite the marked PD L1 expression and Treg numbers, these idiopathic conditions still demonstrated substantial CD8 activation which was easily demonstrated by the Ki67 proliferation index of the recruited CD8 cells in serial sections.

Table 4.

Compilation of immune response to non infectiouschronic inflammatory conditions.

| Category | Inflammatory* cell infiltrate |

Immune Suppression PD L1 |

Immune Suppression FOXP3 |

CD8+ cells | CD8 activation** | CD68 + cells | NK cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eczema (n=6) | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Lichen sclerosis (n=6) | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Ulcerative colitis (n=6) | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Sjogren's disease (n = 2) | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

Inflammatory cell infiltrates, PD L1, FOXP3, CD8, CD68, and NK (CD117 and IL22) positive cells were scored as 0, 1+ (mean less than 10+ cells/200× field over the entire area of infected tissue), 2+ (mean score of 11 to 25+ cell/200× field) and 3+ (mean more than 25+ cells/200× field.

CD8 activation was scored as minimal (weak to no granyzme expression and/or less than 10% of the mononuclear cells + for Ki67) or strong (moderate to strong granzyme expression and/or more than 10% of the mononuclear cells positive for Ki67).

We used the Pearson’s Chi-squared test using the InStat Software for Windows (version 3.36) and tested the null hypothesis that the probability of the expression of PD L1, FOXP3 numbers, CD8 activation (Ki67 index or granzyme expression), CD68, and NK cell numbers in the infectious diseases was equivalent to the probability in the non-infectious inflammatory conditions. We only chose the infectious disease cases with 3+ inflammatory cell infiltrates. The 2×2 table analysis utilized a continuity correction and the null hypothesis was rejected if the significance level at one degree of freedom was below 1%. Such analyses showed that there was a significant decrease in the numbers of FOXP3+ Tregs and CD8 activation in the infectious diseases (p = 0.001) and no significant difference in the extent of PD L1 expression.

Representative examples of the data in the skin are provided in Figure 4. Note that the superficial dermis in eczema (small arrow) showed a strong mononuclear infiltration with many CD68+, CD8+, and CD117+ cells with strong expression of both PD L1 and many Treg cells (panels A–F). The inserts show the strong co-expression of CD8 and PD L1 (panel C) and the lack of co-expression between the Treg cells and PD L1 (panel E). In comparison, the inflammatory cell infiltrates in molloscum and HPV vulvar infections had far fewer inflammatory cells despite the high viral copy number (panels G–L). Also note the absence of FOXP3+ cells in the viral infected skin and that the CD68+ and CD117+ cells were at times found in the epidermis (large arrow) which was unusual in eczema and lichen sclerosus (panels G–L). The CD117+ cells represent both melanocytes (at the epidermal/dermal junction) and NK cells (stroma) based on co-expression with IL22 (22). PD-1 expression closely mirrored the PD L1 expression in the infectious tissues and eczema/lichen sclerosus tissues (data not shown).

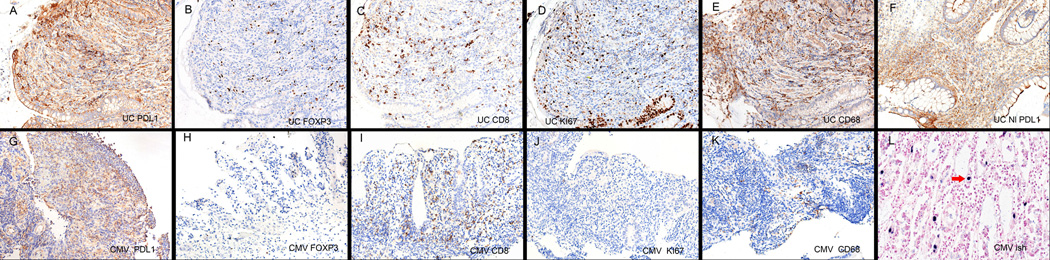

Figure 5 shows a side-by-side comparison of the expression of PD L1 and the numbers of Tregs, CD8+, CD68+ cells and CD8 activation as indicated by Ki67 expression in ulcerative colitis versus CMV infection of the colon (panels A–E versus panels G–K). Note that although PD L1 expression in both conditions is marked and that each condition has many CD8+ and CD68+ cells, the stroma in ulcerative colitis shows far more Tregs and many of the CD8 cells are activated as seen by the Ki 67 expression in the serial section. Panel F shows that the histologically unremarkable colon in cases of ulcerative colitis has PD L1 expression which was not evident in the histologically normal colon adjacent to the CMV infection (data not shown).

Figure 5. Comparison of immune modulation between infectious and noninfectious chronic inflammatory conditions of the colon.

Panels A–E and G–K show side-by-side comparisons of the immune infiltrates of ulcerative colitis versus CMV colitis, respectively. Note the strong PD L1 response in each (panels A, G) as well as the many CD8+ cells in the lamina propria (panels C,I). However, Tregs are common in ulcerative colitis but rarely evident in CMV colitis (panels B, H). Despite the stronger immunosuppressor profile in ulcerative colitis, many more mononuclear cells are proliferating compared to CMV colitis as seen by the Ki67 test (panels D,J) and the CD68 macrophage response is relatively stronger in ulcerative colitis (panels E, K). Panel F shows that PD L1 expression is still markedly elevated in ulcerative colitis even if the colon is histologically unremarkable and panel L shows the high viral copy number associated with this case of CMV colitis.

DISCUSSION

The original and primary finding of this study was to characterize two strong differences in the immune profile when comparing infectious and noninfectious chronic inflammatory processes in humans. Although each showed a strong PD L1 response, the infectious diseases showed minimal Treg infiltration whereas the noninfectious processes showed an intense Treg reaction. Secondly, the strong immunosuppressive phenotype of the noninfectious diseases was ineffectual in preventing CD8 activation as revealed by the high Ki67 index and robust granzyme expression. This was in sharp contrast to the infectious disease processes where the recruited CD8 cells were mostly quiescent. An important clinically related observation from these data is that they may provide a molecular basis for the observation that anti-PD L1 therapy tends to be effective in eradicating viral infections since it would be expected to induce CD8 proliferation and cytotoxic behavior by removing the blockage of such by PD L1 (5–11). Also, there are some diseases in which the question of auto-immune versus infectious is still controversial, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. One may postulate from the current study that an immune profile rich in Treg cells and activated CD8 cytotoxic cells would be more likely to be noninfectious.

The immune system has various checkpoints built into its complex pathways that attempt to contain the foreign antigen but not at the expense of excessive tissue damage. A major subset of T lymphocytes, the Tregs, which can be identified by their nuclear protein FOXP3, are a classic example of such a checkpoint which can reduce the risk of autoimmune diseases. Much attention has focused recently on two separate checkpoint inhibitors, PD L1 and CTLA-4. These proteins are able to bind to molecules such as PD-1 or CD80 which, in turn, ultimately reduces the activity of the recruited cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocyte which is the key cell in attacking both cancer and viral/bacterial foreign antigens. The importance of blocking either PD L1 or CTLA-4 has been recently underscored in cancer treatment where several groups have shown a strong anti-tumor response after removing either checkpoint inhibition (24–29). Several of these manuscripts have stressed the importance of a strong CD8 presence in the tumor as a predictor of success after anti-PD L1 therapy and have likewise shown that the CD8 cells shift from a quiescent to activated state after the PD L1 blockage has been removed (24,25).

The blockage of PD L1 or CTLA4 by the appropriate antibody (eg MPDL3280A for PD L1 and ipilimumab for CTCL4) has been associated with autoimmune manifestations. For example, 17% of people in one study that received ipilimumab developed autoimmune hypophysitis (28). Still, the reporting of auto-immune disease after antibody therapy against PD L1 is rare (24,25). Our results suggest that one possible explanation may be that autoimmune diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Sjogren’s disease, and lichen sclerosus typically are associated with an immunosuppressor profile that includes other checkpoints besides PD L1 such as Tregs. Further, the PD L1 in autoimmune diseases may not be effective given the strong CD8 activation in such cases. The reason(s) why CD8 cytotoxic cells are able to circumvent the strong PD L1 and Treg presence in noninfectious chronic inflammatory states that are presumed to be autoimmune in origin are poorly understood and were not addressed in this study.

Our results suggest that immune checkpoints and their role in infectious diseases may be more straightforward than with noninfectious chronic inflammatory states. Despite studying a wide range of viral infections and the common bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori, we could not find any infectious disease where Tregs were a substantial part of the inflammatory infiltrate. However, PD L1 expression was invariably strong in the mononuclear cells that were plentiful in many of these infectious disease tissues. Unlike autoimmune chronic inflammatory states, the PD L1 in the infectious disease cases may have been actively suppressing the immune response as indicated by the lack of granzyme expression and the rarity of CD8 proliferation. Indeed, we were able to use a mouse model that utilized the ability of reovirus to specifically target cancer cells to demonstrate that reoviral RNA proliferation strongly enhanced PD L1 production with a concomitant loss of granyzme expression. Similarly, by using various myeloma cell lines with marked differences in sensitivity to reovirus infection, we were able to demonstrate that reovirus infection per se was strongly correlated with enhanced PD L1 expression.

Reovirus has become an important agent in cancer treatment given its ability to target cancer cells (21, 23). Concomitant chemotherapy has been shown to enhance the ability of reovirus to cause tumor lysis by enhancing the productive infection by the virus which, in turn, can activate the caspase-3 apoptosis cascade (21,23). It has been suggested that this enhanced oncolysis may have two causes: direct virus mediated tumor cell destruction and the increased immune state induced by the virus. This study showed that reovirus infection can "prime" the immune system by increasing the number of CD8 and NK cells around the tumor cells but that the concomitant PD L1 up regulation may reduce the ability of these recruited immune cells to kill the virus/tumor cells. This, in turn, suggests that anti-PD L1 therapy in conjunction with reovirus may enhance tumor lysis by removing the checkpoint inhibition on the CD8 and NK cells that have been recruited to the area of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors great appreciate the assistance of Dr. Margaret Nuovo with the photography/computer imaging, Dr. Richard Vile who provided the B16 melanoma associated mouse tumors, Dr. Radhashree Maitra who provided some of the cells treated with reovirus, and Dr. Virginia Nivar-Folcik for a critical review of the manuscript.

Funding Support: The Lewis Foundation (GJN) and NIH grant T32CA 165998 (DS)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE/ CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oldstone MB. Virus-lymphoid cell interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12756–12758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merelli B, Massi D, Cattaneo L, Mandala M. Targeting the PD1/PD-L1 axis in melanoma: biological rationale, clinical challenges and opportunities. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;89:140–165. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saresella M, Rainone V, Al-Daghri NM, et al. The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in human pathology. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:259–267. doi: 10.2174/156652412799218903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiss KA, Forde PM, Brahmer JR. Harnessing the power of the immune system via blockade of PD-1 and PD L1: a promising new anticancer strategy. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:459–475. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zdrenghea MT, Johnston SL. Role of PD-L1/PD-1 in the immune response to respiratory viral infections. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakthivel P, Gereke M, Bruder D. Therapeutic intervention in cancer and chronic viral infections:antibody mediated manipulation of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012;7:10–23. doi: 10.2174/157488712799363262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikebuchi R, Konnai S, Shirai T, et al. Increase of cells expressing PD-L1 in bovine leukemia virus infection and enhancement of anti-viral immune responses in vitro via PD-L1 blockade. Veterinary Research. 2011;42:103–107. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larrubia JR, Benito-Martinez S, Miquel J, et al. Bim-mediated apoptosis and PD-1/PD-L1 pathway impair reactivity of PD1+/CD127− HCV-specific CD8+ cells targeting the virus in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Cellular Immunology. 2011;269:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Zhang E, Ma Z, et al. Enhancing virus-specific immunity in vivo by combining therapeutic vaccination and PD-L1 blockade in chronic hepadnaviral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozako T, Yoshimitsu M, Fujiwara H, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 expression in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 carriers and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patients. Leukemia. 2009;23:375–382. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier H, Isogawa M, Freeman G, Chisari F. PD-1:PD-L1 interactions contribute to the functional suppression of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the liver. J Immunol. 2007;178:2714–2720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimura T, Okuyama R, Ito Y, Aiba S. Profiles of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in eczematous dermatitis, psoriasis vulgaris and mycosis fungoides. J Dermatopathology. 2008;158:1256–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu QT, Saruta M, Avanesyan A, et al. Expression and functional characterization of FOXP3+CD4+ regulatory T cells in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:191–199. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki M, Jagger A, Konya C, et al. CD8+CD45RA+CCR7+FOXP3+ T cells with immunosuppressive properties: A novel subset of inducible human regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:2118–2130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman S, Gudetta B, Fink J, et al. Compartmentalization of immune responses in human tuberculosis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2211–2224. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song M-Y, Hong C-P, Park SJ, et al. Protective effects of Fc-fused PD-L1 on two different animal models of colitis. Gut. 2015;64:260–271. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sunagawa T, Yonamine Y, Kinjo F, et al. HLA class-I-restricted and colon-specific cytotoxic T cells from lamina propria lymphocytes of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21:381–389. doi: 10.1023/a:1013169509123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welters MJ, Kenter GG, Piersma SJ, et al. Induction of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunity in cervical cancer patients by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 long peptides vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:178–187. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liblau RS, Wong FS, Mars LT, Santamaria P. Autoreactive CD8 T cells in organ-specific autoimmunity: emerging targets for therapeutic intervention. Immunity. 2002;17:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalish RS, Askenase PW. Molecular mechanisms of CD8+ T cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity: implications for allergies, asthma, and autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:192–199. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denney L, Aitken C, Li CK-F, et al. Reduction of natural killer but not effector CD8 T lymphocytes in three consecutive cases of severe/lethal H1N1/09 influenza A virus infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuovo GJ, Garofalo M, Valeri N, et al. Reovirus-associated reduction of microRNA-let-7d is related to the increased apoptotic death of cancer cells in clinical samples. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1333–1344. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes T, Becknell B, Nuovo GJ, et al. Stage three immature human natural killer cells found in secondary lymphoid tissue constitutively and selectively express the TH17 cytokine interleukin-22. Blood. 2009;113:4008–4010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kottke T, Chester J, Ilett E, et al. Precise scheduling of chemotherapy primes VEGF-producing tumors for successful systemic oncolytic virotherapy. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1802–1812. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galea-Lauri J, Farzaneh F, Gaken J, Gaken J. Novel costimulators in the immune gene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 1996;3:202–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mocellin S, Benna C, Pilati P. Coinhibitory molecules in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillard T, Yedinak CG, Alumkal J, Fleseriu M. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy associated autoimmune hypophysitis: serious immune related adverse events across a spectrum of cancer subtypes. Pituitary. 2010;13:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s11102-009-0193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao X, Ahmadzadeh M, Lu YC, et al. Levels of peripheral CD4(+)FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells are negatively associated with clinical response to adoptive immunotherapy of human cancer. Blood. 2012;119:5688–5696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]