Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Indigenous social determinants of health, including the ongoing impacts of colonization, contribute to increased rates of chronic disease and a health equity gap for Indigenous people. We sought to examine the health care experiences of Indigenous people with type 2 diabetes to understand how such determinants are embodied and enacted during clinical encounters.

METHODS:

Sequential focus groups and interviews were conducted in 5 Indigenous communities. Focus groups occurred over 5 sessions at 4 sites; 3 participants were interviewed at a 5th site. Participants self-identified as Indigenous, were more than 18 years of age, lived with type 2 diabetes, had received care from the same physician for the previous 12 months and spoke English. We used a phenomenological thematic analysis framework to categorize diabetes experiences.

RESULTS:

Patient experiences clustered into 4 themes: the colonial legacy of health care; the perpetuation of inequalities; structural barriers to care; and the role of the health care relationship in mitigating harm. There was consistency across the diverse sites concerning the root causes of mistrust of health care systems.

INTERPRETATION:

Patients’ interactions and engagement with diabetes care were influenced by personal and collective historical experiences with health care providers and contemporary exposures to culturally unsafe health care. These experiences led to nondisclosure during health care interactions. Our findings show that health care relationships are central to addressing the ongoing colonial dynamics in Indigenous health care and have a role in mitigating past harms.

Globally, type 2 diabetes disproportionately affects Indigenous populations,1 with documented rates in Canada 3–5 times higher in Indigenous compared with non-Indigenous populations.2,3 Indigenous people tend to acquire diabetes at younger ages, have complications sooner4,5 and have poorer treatment outcomes.6 In Canada and other countries that share a colonial history, health inequities arising from the effects of colonization include deeply rooted disparities in the social determinants of health, social exclusion, political marginalization and historical trauma.7–9 Recent research recognizes that specific determinants contribute to inflated rates of diabetes and other illnesses among colonized peoples, negatively affecting disease management and outcomes in unique ways.10,11 In this study, we look more closely at how such determinants become embodied and enacted during clinical encounters.

Part of a larger investigation known as “Educating for Equity,” our study forms one component of an international collaboration involving researchers in Australia, New Zealand and Canada. As medical educators, physicians and social scientists, our goal in Canada has been to develop curricula for family physicians and health care providers working with Indigenous populations. This paper draws on a data subset that informs curriculum development, namely the health care experiences of diverse Indigenous patients with type 2 diabetes. Our purpose is to examine opportunities that inspire and empower patients in their care journey, as well as moments that disarm and disengage Indigenous patients from formal health care systems. Our analysis draws on structural violence as a theoretical framework for identifying institutionalized forms of harm that systematically undermine the care extended to marginalized populations.12 This is therefore our response to a call to action by Farmer and colleagues, to “link social analysis to everyday clinical practice.”12 In this spirit, Canadian health care leaders and providers have moved health systems toward addressing recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada recommendations, particularly to “acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies…”13, some of which are ongoing, and to engage in “skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights and antiracism.”13

Methods

Research sites

Drawing on existing research relationships in our regions, we invited 5 Indigenous organizations from the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario to participate in sequential focus groups concerning diabetes care (Table 1). One small remote First Nation reserve declined to participate in focus groups out of discomfort with speaking in front of other community members, but agreed to one-on-one interviews. Sample questions from each section of the full-session interview guide were pilot tested in an urban site in Alberta, which informed subsequent groups.

Table 1:

Final sample by focus group site

| Site | Partner(s) | Male | Female | Total n = 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Southern Alberta | Indigenous Health Centre | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Urban Northern Ontario | Indigenous Health Centre and Friendship Centre | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Rural British Columbia (Vancouver Island) | First Nation Community | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Rural Alberta | First Nation Community | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Remote Northern Ontario (individual interviews) | First Nation Community | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Sources of data

Recruitment combined purposive, convenience and snowball sampling. Posters advertised the study in Indigenous health centres and Friendship Centres at research sites. Community liaisons helped with recruitment and screening. All participants self-identified as Indigenous, were more than 18 years of age, lived with type 2 diabetes, had received care from the same physician for the previous 12 months, spoke English and (with the exception of individual interviewees) had agreed to participate in all 5 focus group sessions. Participants were not asked to disclose Indigenous status or affiliation.

Data collection

We implemented a series of semistructured sequential focus groups in 4 sites in 3 Canadian provinces. The same groups of participants attended five 2.5- to 3-hour sessions in their clinic or community centre over a 1- to 2-week period. The sequential sessions allowed for deep exploration of stories that unfolded in response to daily topics. The method fostered daily reflection and honoured Indigenous ways of knowing and sharing.15 The sessions were attended only by participants and members of the local research team and were organized around 5 broad discussion areas: understandings of diabetes, risk, lifestyle and prevention, stress and diabetes, health care experiences and a review or wrap-up. Sessions 2–5 began with member checking from previous discussion. In this analysis, we mainly draw on data emerging from the 4th session’s focus on health care experiences; however, we included participants’ health care experiences shared in any of the 5 sessions in this analysis. We provided participants with a light meal and a $50 honorarium at each session to acknowledge information sharing and time commitments to the project.

Analysis

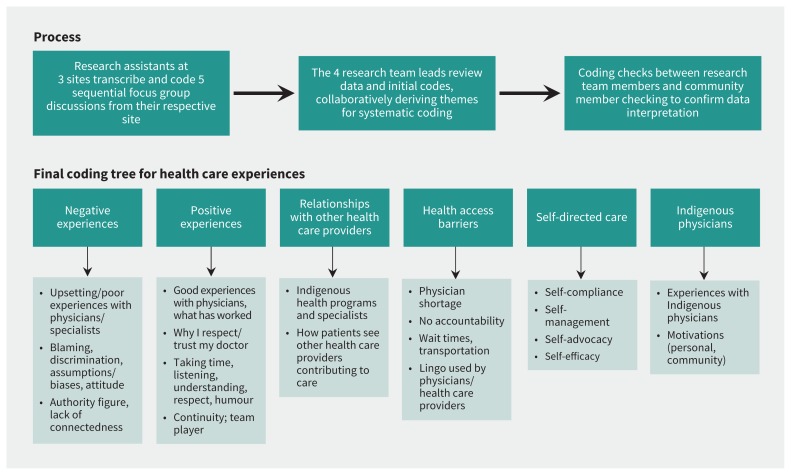

All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed. Three graduate-trained research assistants coded the transcripts under the supervision of the principal investigators. We held weekly meetings with the entire Education for Equity team during data collection to facilitate oversight and debriefing. The 4 principal investigators then analyzed the coded data using a phenomenological thematic analysis model (Figure 1). This approach, which derives themes from the data, seeks “to understand the hidden meanings and the essence of an experience together with how participants make sense of these.”16 Random coding checks were employed to ensure consistency.

Figure 1:

Coding process and themes.

We used QSR NVivo 9+ to manage transcripts and study-related data; attending to data saturation was not applicable. After completion of the preliminary analysis, a community gathering was held at each site to meet with participants, health care staff and other community members. This allowed further member checking for participant confirmation of data and interpretation.17

Ethics approval

We followed Canadian Tri-Council guidelines for ethical research involving First Nations, Inuit and Métis participants.14 Ethics approval was granted from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board and, subsequently, each investigator’s university, in addition to each Indigenous research site.

Results

Each sequential focus group had 6–8 participants, and 3 individual interviews were conducted at the remote site, for a total of 32 participants in the study. All participants were volunteers, meaning that no one refused to participate, nor did anyone drop out. The final sample included 12 men and 20 women who ranged in age from 45 to 79 years. Duration of diabetes ranged from 1.5 years to more than 25 years.

An examination of transcripts suggests that focus groups included participants who were status and non-status First Nations as well as Métis. We estimate that more than half of the participants were First Nations.

Patients’ experiences with diabetes care are categorized into 4 themes: the colonial legacy of health care, the perpetuation of inequities, structural barriers to care and the role of health care relationships in mitigating harm (Table 2). Underlying experiences shared at urban and rural sites mapped to the same themes, which suggests that geography did not play a large role in the nature of health care interactions across sites.

Table 2:

Themes in reported experiences of diabetes care

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

|

Theme 1: Colonial legacy of health care Indigenous patients’ health care experiences are mediated by historical relationships with the government | |

| Residential School |

|

| Tuberculosis, public health and power relations |

|

| Mistrust and avoidance |

|

|

Theme 2: The perpetuation of inequities Indigenous patients’ health care experiences are influenced by contemporary interactions with systems that perpetuate historical relations | |

| Denied care |

|

| Inferior care |

|

| Policies unsupportive of culture |

|

|

Theme 3: Structural barriers to care Indigenous patients’ health care experiences are influenced by systems of care that prevent patient-centred care approaches that could repair or build relationships | |

| First Nations health policies |

|

Challenges to accessing care

|

|

|

Theme 4: The role of health care relationships in mitigating harm Relationship with providers affects how interactions are interpreted by Indigenous patients and whether or not advice is followed | |

| Presumed authority of providers leading to relationship breakdown |

|

| Good therapeutic relationships grounded in relationship-centred approach |

|

Theme 1: The colonial legacy of health care

For several participants, diabetes care was mediated by traumatic historical relations between Indigenous people in Canada and the government, most often materializing in avoidance of health care systems, mistrust of physicians and resistance to other health service providers.

Participants described avoidance and resistance to health care providers when interactions stirred memories of negative childhood experiences from residential schools.18 These memories could be easily triggered in the clinical encounter when doctors were too prescriptive or authoritarian, making participants feel “tired of being told what to do” (BC-FN-2). One participant related such experiences to what physicians sometimes label “noncompliance,” noting that physicians often “can’t figure out why [patients] are doing a certain thing, or why they’re not looking after their sugar properly” (ON-FN-2). Multiple participants suggested that health care providers lacked education about residential schooling, including long-term effects: “I think the doctors do have to be educated on what happened, and also to realize that it’s intergenerational” (ON-URBAN-2). Memories of lining up to be attended to, being ordered what to do and the presumed authority of government or church workers were often triggered by similar experiences in health care today, aggravating distrust.

For some participants, another trigger involved past experiences with federally sponsored on-reserve health care, examples of which included past government providers using coercion to force compliance with the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine (Box 1).

Box 1: Patient quotes.

Four participants in Alberta remembered being given the vaccine while lined up for treaty payments: “If you had TB, Miss M. would go to that big dance hall with needles. We’d all be in line waiting for our paychecks, you know, a payment” (AB-FN-3). This could also occur unexpectedly in public places: “That matron was very strict, eh?...One time a person was walking on the road...was on the list.…she gave that person a needle right on the road” (AB-FN-3). Finally, basic dignity was often not respected: “Every year we get x-rays and she have to take my clothes off, [in front] of my son-in-law or mother-in-law. [The people didn’t] want to go in there” (AB-FN-4). One participant summed up the discussion: “That’s not very proper … Treated us like dirt” (AB-FN-6).

Mistrust emerged as a substantial subtheme that clearly stemmed from historical experiences. Participants in 1 group suspected that during the mid-20th century, Indigenous patients with tuberculosis “were used as guinea pigs” (AB-FN-5), presumably observed or tested upon without access to the same interventions provided to non-Indigenous patients. This speculation resonated in a discussion from another focus group, where a participant described feeling like a “rat” whenever new medications were prescribed to control diabetes and epilepsy (BC-FN-1).

Theme 2: The perpetuation of inequities

Participants recalled contemporary experiences with health care systems that reinforce historical relationships through ongoing racism, discrimination and stereotyping. These included being denied care, perceptions and experiences of inferior care and policies unsupportive of cultural practices in care.

Participants experienced interactions that they interpreted as racially motivated on the part of health care providers. One First Nations man described having travelled a long distance from his home community to an urban centre for what he understood would be a biopsy, only to be sent home without an explanation or having the procedure completed (Box 2).

Box 2: Patient quote.

“We got all the way there and this doctor, it seemed like he was prejudiced or something, ‘oh it doesn’t look like there’s anything wrong with you.’ Didn’t examine my back or nothing and said ‘see ya.’ All the way to Vancouver for that. Some places you do get treated poorly because of our skin colour. That makes me so mad, I feel like taking a knife and saying ‘look, isn’t my blood the same colour?’”

Another participant recalled sitting in a waiting room and overhearing a physician say to his secretary: “Skip through these so we can get to the real patients” (BC-FN-5). The participant described watching as the secretary then called 2 Indigenous women and then an older Indigenous man for their appointments. His anger led to abandoning the appointment after speaking up: “As I left, I went over to her and said ‘we’re all real patients, all of us.’”

One participant recalled when he first received his diabetes diagnosis; he had gone to the hospital with flu-like symptoms and bleeding from the mouth. Emergency department staff assumed he had been “sniffing nail polish,” although his blood glucose level would later prove dangerously high (AB-URBAN-1) (Box 3).

Box 3: Patient quote.

Although discussions were focused on diabetes, one participant shared how his experience with cancer treatment influenced future interactions with the health care system. He described feeling discriminated against by both his physician and the wider institution. In one instance, he was made to feel as though he were “contagious” when a physician preparing him for chemotherapy remained on the far side of the examining table. In a second instance, he discovered that the hospital employed an “Aboriginal liaison” hired to help clients like himself navigate care, though the liaison was not permitted on the floor where he received treatment, leaving him to conclude that it was “just a token position so they could get some funding” (ON-URBAN-2).

A lack of consideration for cultural practices was also discussed. Some participants acknowledged that, increasingly, hospitals set aside spaces for Indigenous ceremony, but noted that access to these is not always possible for patients confined to a bed. Likewise, it is not uncommon for Indigenous extended families to come to hospitals in support of a patient. Tensions arising from visitations resonated for 1 participant who was told during an interaction with a senior hospital administrator to “tell your community that we’re not running a lodging service here” (ON-URBAN-2). For this participant, “when one of us gets sick, our whole family is there. He didn’t like that.” The administrator’s words led the patient to stop engaging in health services, perceiving a bias against Indigenous clients and disregard for family supports.

Theme 3: Structural barriers to care

Participants discussed barriers at systemic levels that prevent effective care, including First Nations health policies and challenges around access, such as physician shortages, geographic isolation, appointment time allocation and health care worker turnover or continuity of care.

Often, participants recalled instances where new physicians or residents came to their communities to gain experience with complex and diverse diseases before moving on to presumably “better places” (AB-FN-3). Participants felt that once doctors gain experience, “they want more money here, and if they don’t get it, they quit and move on” (AB-FN-3). A considerable challenge identified by participants was that each visit to a clinic off-reserve could lead to interacting with a new provider, retelling one’s history and leaving with yet another care plan. A shortage of on-reserve physicians threatened continuity of care. Although participants were told to go to their family doctor, they found it difficult to get a timely appointment. This led some participants to question doctor – patient ratios for Indigenous people across Canada, arguing that concern over doctor shortages should be amplified for populations with disproportionate rates of diabetes (Box 4).

Box 4: Patient quote.

“We need more doctors, period…Maybe 5 or 6 doctors here 24 hours a day, not all at the same time, but to look after the people with diabetes…There’s nobody doing too much about it…There’s about 10 or 15 doctors [in town] for a population of how many thousand, 10 000 people? And we don’t get that…7,000 Indian people here on the reserve, what’s the ratio of doctor for people [here]?”

Participants argued that high-volume clinical services, with short clinical interactions (10 min), inadequately address complex care issues among Indigenous patients, which impedes the development of appropriate care relationships. This was described by one participant as a race to fit as many patients in as possible (ON-FN-3). Another declared that she would “die of old age” before finally being placed with a family doctor (ON-FN-1). In the mean-time, she dealt with the doctor at a walk-in clinic whose impersonalized care made her feel like “somebody on an assembly line.”

Particularly troubling was the lack of time physicians had to visit with patients, especially when physicians instructed patients to book another appointment when presenting with multiple concerns. Participants at 1 site (BC-FN) found this more common among younger practitioners, who were often seen as unwilling to hear all that a patient considers important to share. For other participants, the greatest barrier emerged in the lack of access to trained professionals on their home reserves, resulting in the need to travel to surrounding non-Indigenous communities for care.

Also discussed were health policies of the federal government, which govern First Nations health care services in Canada. Some participants reported being unable to secure necessary supplies, such as insulin pumps, because of the complexity of the government funding forms and physicians ill-disposed or unwilling to fill these out. Participants at 2 on-reserve sites spoke of the government’s Health Transfer Policy, believing that the reserves were not supported in taking over control of their health services, which set them up for failure. Such policies were seen to lead to inequity between communities, with smaller reserves receiving fewer resources.

Theme 4: The role of the health care relationship in mitigating harm

The quality of relationships between health care providers and participants was integral to perceptions of the effectiveness of clinical interactions.

Good therapeutic relationships were described as having the quality of humility, whereby providers would admit when they were unsure and take time to investigate further. Humility, which resonated culturally with participants, was described as having won over initially reluctant patients. One doctor was seen to level the power imbalance with his patient by beginning with an admission that he did not have much training in diabetes. With this, he told a participant “I want you to teach me,” to which the participant felt honoured to be invited to work together (ON-URBAN-2).

Although exceptionally uncommon, participants appreciated physicians who phoned them at home (ON-URBAN-5). One physician took time to involve family and partners in care plans, and another was praised for listening (BC-URBAN-2). Participants also appreciated doctors who were not condescending when patients wished not to be referred to certain specialists perceived to scold them (AB-FN-5) (Box 5).

Box 5: Patient quote.

“She listens more than any doctor that I’ve had, and she actually diagnosed two of my family members with things, whereas their own family doctors couldn’t even diagnose it because they were just pushing the pills.”

Doctors who showed interest in Indigenous cultural practices that contributed to patient health were also considered effective. Instead of solely focusing on whether or not a patient was taking traditional medicines, one physician was described as enquiring about “eating habits, wild food and what traditional games we have out there, and questions about spirituality” (BC-FN-1).

Negative interactions were characterized by physicians “lecturing” patients to the point that participants refused to share simple information, like what they had eaten for breakfast (AB-FN-6). One participant disclosed having not elaborated on their symptoms because of the absence of meaningful communication: “every time you tell him a story, he’ll add a pill to your collection” (AB-FN-1). Participants argued that such interactions reflected a presumed authority over patients on the part of many doctors. Physicians who focused too directly on what was wrong, on quick remedies and on getting the patient out the door were perceived to have a cold persona (ON-URBAN-1). Any presumed authority or power differential was considered fundamental to the breakdown of health care relationships.

Finally, the physical space in which clinical interactions took place was important. Participants often wanted services provided in their communities or in Indigenous health centres. Examination rooms could stir mistrust before a clinical interaction even began. This occurred with 1 doctor who displayed a picture of the “holy land” on his office wall that read “repent” (ON-URBAN-7). Presence of the physician’s religious values made the patient uneasy about discussing his or her own, including use of traditional medicine. Such visual cues inspired participants to lie to their physicians: “because I don’t want to hear the lecture and don’t want to hear the ‘well you know if you keep this up you’ll be dead by this age’” (ON-URBAN-3). This lends additional insight into why, in multiple sites, participants who admitted to seeking traditional medicines for their diabetes would not disclose doing so to their doctors.

Interpretation

The team undertook a qualitative examination of Indigenous patients’ stories emanating from a sequential focus group method that concerned diabetes care experiences using a structural violence lens. We found that interactions and engagement with health services are influenced by personal and collective historical experiences with health care providers and contemporary exposures to culturally unsafe health care. Participants related such experiences to specific health policies and systemic discrimination in health care systems.

Participants reported that rushed appointments, writing prescriptions or medicating complaints, not listening and negative judgments regarding Indigenous customs and communities created a lack of confidence in the health system and provider. Together, these experiences led to participants not disclosing all of their symptoms or health behaviours.

In addition, our findings show that health care relationships are central to addressing the ongoing colonial dynamics in Indigenous health care and have a role in mitigating past harms. Participants described scenarios in which trust was rebuilt. Notably, participants provided examples of how positive relationships that shifted the power balance in clinical settings provided renewed confidence in health care systems. The positive therapeutic relationships described by participants involved physicians who showed humility, empathy and patience, and who took a genuine interest in the patient.

Other studies have similarly reported on the impact of the colonial legacy and the perpetuation of inequities on Indigenous health.13,19–21 Our results add to this evidence base, particularly to studies that found that Indigenous health care experiences continue to be shaped by “racism, discrimination and structural inequities.”22,23

Towle and colleagues24 propose a model for improved relationship building with Indigenous patients by attending to issues of history, trust and time. Our findings support such strategies and deepens the elements and approaches for consideration by linking physician characteristics (e.g., empathy, humility), as well as structural and systems determinants, to clinical approaches. The structural violence lens is useful in revealing and understanding barriers to diabetes care for Indigenous people; however, solutions to improve access may be found in health equity,25,26 cultural safety and enhanced patient-centred care approaches.27,28 Indeed, health equity and cultural safety are key concepts framing any change13,29 and are embedded in the updated CanMEDs Physician Competency Framework30 and the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Core Competencies.29

Attention to antiracism education, structural competency31 and advocacy for working with Indigenous populations holds great potential to address issues identified, because the physician as health advocate is expected for the promotion of health equity.30 However, our study also reinforces the need for targeted strategies to enhance health care provider approaches to Indigenous clinical encounters, such as with the routine employment of trauma-informed care32 and enhanced patient-centred care models for Indigenous patients. Findings presented here have use in identifying crucial changes in patient-centred care approaches to reflect the needs of Indigenous patients, and highlight potential adaptations to core patient participation, health care relationships and care context elements of patient-centred care.

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted in 3 provinces and in rural, remote and urban Indigenous communities. This diversity allowed the research team to look for shared experiences across multiple health jurisdictions. In addition, the investigators were both Indigenous and non-Indigenous medical educators from social and clinical sciences, which facilitated the inclusion of multiple perspectives.

We relied on purposive, convenience and snowball sampling, which although not uncommon in community-based work, may result in participant selection bias; for example, participants may have personal motivation for volunteering. Although the focus groups were held after work hours, the requirement of participation in 5 sessions may have restricted the ability of members of some demographic groups to participate.

Conclusion

Our findings confirm that Indigenous determinants of health are embodied and enacted during regular encounters for diabetes care. Improvements in Indigenous peoples’ experiences with diabetes care are seen when patients have positive and more equitable relationships with health care providers and organizations. Our findings point to strategies that health care providers, health organizations and policy-makers can implement to improve cultural safety for Indigenous patients with diabetes, while beginning to respond to recommendations in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action. Most evident in our findings are opportunities to improve training in medical and health education, including enhanced patient-centred care approaches for Indigenous patients and cultural safety training for health care providers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Educating for Equity research team members who assisted with literature reviews, data collection and data coding: Anh Ly, Elaine Boyling, Sarah Elliot, Han Han, Tiinaa Liinamaa, Jo-ann Parker and Tanu Gamble.

Footnotes

Infographic available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.161098/-/DC1

Competing interests: Rita Henderson and Lynden Crowshoe report grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the conduct of the study. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Kristen Jacklin contributed to the methodological design, data collection and analysis, and lead manuscript development. Rita Henderson contributed to analysis, manuscript development and review. Michael Green contributed to the methodological design, data analysis and manuscript development and review. Leah Walker, Betty Calam and Lynden Crowshoe assisted with the research design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript review. All of the authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Funding: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded this study through the International Collaborative Indigenous Health Research Partnership grant (#IDP-103986, grant no. RT735835), in partnership with the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. The funder had no role in the research.

References

- 1.Yu CH, Zinman B. Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in aboriginal populations: a global perspective. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;78:159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris SB, Naqshbandi M, Battacharyya O, et al. Major gaps in diabetes clinical care among Canada’s First Nations: Results of the CIRCLE study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;92:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyck R, Osgood N, Lin TH, et al. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non-First Nations adults. CMAJ 2010;182:249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dannenbaum D, Kuzmina E, Lejeune P, et al. Prevalence of diabetes-related complications in First Nations communities in Northern Quebec (Eeyou Istchee), Canada. Can J Diabetes 2008;32:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanley AJ, Harris S, Mamakeesick M, et al. Complications of type 2 diabetes among Aboriginal Canadians. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2054–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyck RF, Tan L. Rates and outcomes of diabetic end-stage renal disease among native people in Saskatchewan. CMAJ 1994;150:203–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health 2005;96:S45–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, et al. Determinants of indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: beyond the social. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 2009;374:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richmond CA, Ross N. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: a critical population health approach. Health Place 2009;15:403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maar MA, Gzik D, McGregor L, et al. Serious complications for patients, care providers and policy makers: tackling the structural violence of First Nations people living with diabetes in Canada. Int Indigenous Policy J 2011; 2 (1). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, et al. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med 2006;3:e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to action. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council of Canada, Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2): ethical conduct for research with humans. 2nd ed Ottawa: Interagency Secretariat on Research Ethics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacklin K, Ly A, Green M, et al. An innovative sequential focus group method for investigating diabetes care experiences with Indigenous peoples in Canada. Int J Qual Meth 2016;15:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grbich C. Qualitative data analysis: an introduction. London (UK): Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creswell J, Hanson W, Clark Plano VL, et al. Qualitative research designs: selection & implementation. Couns Psychol 2007;35:236–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan P. Unsettling the settler within: Indian residential schools, truth telling, and reconciliation in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Towle A, Godolphin W, Alexander T. Doctor-patient communications in the Aboriginal community: Towards the development of educational programs. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bird SM, Wiles JL, Okalik L, et al. Living with diabetes on Baffin Island. Can J Public Health 2008;99:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barton SS, Anderson N, Thommasen HV. The diabetes experiences of Aboriginal people living in a rural Canadian community. Aust J Rural Health 2005;13: 242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browne AJ. Clinical encounters between nurses and First Nations women in a Western Canadian hospital. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2165–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walls ML, Gonzalez J, Gladney T, et al. Unconscious biases: racial microaggressions in American Indian health care. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towle A, Godolphin W, Alexander T. Doctor-patient communications in the Aboriginal community: towards the development of educational programs. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008;372:1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, et al. Closing the health equity gap: evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, et al. Patient-centred medicine: transforming the clinical method. 2nd ed. UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, et al. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavallee B, Neville A, Anderson M, et al., editors. First Nations, Inuit, Métis Health core competencies: a curriculum framework for undergraduate medical education. Ottawa: Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada, and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Fridkin A. Addressing trauma, violence, and pain: research on health services for women at the intersections of history and economics. In: Hankivsky O, de Leeuw S, Lee J-A, et al., editors. Health inequities in Canada: intersectional frameworks and practices. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]