Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Human islets from type 2 diabetic donors are reportedly 80% deficient in the p21 (Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase, PAK1. PAK1 is implicated in beta cell function and maintenance of beta cell mass. We questioned the mechanism(s) by which PAK1 deficiency potentially contributes to increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Non-diabetic human islets and INS 832/13 beta cells cultured under diabetogenic conditions (i.e. with specific cytokines or under glucolipotoxic [GLT] conditions) were evaluated for changes to PAK1 signalling. Combined effects of PAK1 deficiency with GLT stress were assessed using classic knockout (Pak1−/−) mice fed a 45% energy from fat/palmitate-based, ‘western’ diet (WD). INS 832/13 cells overexpressing or depleted of PAK1 were also assessed for apoptosis and signalling changes.

Results

Exposure of non-diabetic human islets to diabetic stressors attenuated PAK1 protein levels, concurrent with increased caspase 3 cleavage. WD-fed Pak1 knockout mice exhibited fasting hyperglycaemia and severe glucose intolerance. These mice also failed to mount an insulin secretory response following acute glucose challenge, coinciding with a 43% loss of beta cell mass when compared with WD-fed wild-type mice. Pak1 knockout mice had fewer total beta cells per islet, coincident with decreased beta cell proliferation. In INS 832/13 beta cells, PAK1 deficiency combined with GLT exposure heightened beta cell death relative to either condition alone; PAK1 deficiency resulted in decreased extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) phosphorylation levels. Conversely, PAK1 overexpression prevented GLT-induced cell death.

Conclusions/interpretation

These findings suggest that PAK1 deficiency may underlie an increased diabetic susceptibility. Discovery of ways to remediate glycaemic dysregulation via altering PAK1 or its downstream effectors offers promising opportunities for disease intervention.

Keywords: Beta cell mass, Diet-induced obesity, Insulin secretion, PAK1, Prediabetes, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

At the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, overall islet mass and/or function may be decreased by more than 50% [1–3], suggesting that the progressive degeneration of functional beta cell mass is occurring during the pre-diabetic phase, prior to the development of frank type 2 diabetes. Factors causal in the demise of beta cell function and/or mass in the face of diabetogenic stress are highly sought after.

Previous studies have implicated the serine/threonine p21 (Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) as a positive and required factor in both beta cell function [4–6] and maintenance of beta cell mass [7, 8]. For example, multiple reports show that Pak1−/− knockout (Pak1 KO) mice fed a standard (non-diabetogenic) diet are glucose intolerant, related to impairments in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from islets ex vivo [4] and serum insulin release in vivo [5]. Despite this, Pak1 KO mice did not develop fasting hyperglycaemia nor exhibit profound changes in beta cell mass. This contrasts with other reports citing an important role for PAK1 in beta cell proliferation and survival ex vivo [7, 8]. Notably though, the requirement for PAK1 in beta cell proliferation and survival was identified only under conditions of islet stress ex vivo, while the Pak1 KO mice were studied only under standard conditions. It remains possible that alterations in beta cell mass would not manifest in the Pak1 KO mice until challenged with an additional stress to the pancreatic islets, such as chronic consumption of a high-fat diet.

It is established that high-fat diet intake leads to the development of insulin resistance in both humans and animals [9, 10] and that beta cells compensate by increasing insulin release under fasting conditions to quell the ensuing hyperglycaemia, predominantly through expansion of the beta cell mass [11, 12]. However, chronic exposure to saturated fatty acids, such as palmitate, promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines which are cytotoxic to pancreatic beta cells [13, 14]. In addition, saturated fatty acids generate production of reactive oxygen species, leading to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [15], with both processes ultimately leading to beta cell apoptosis. Whether PAK1 is involved in the in vivo compensatory mechanism to maintain euglycaemia in the face of high-fat diet-induced stress, and/or for protecting beta cells from palmitate-induced stress, has remained untested.

Methods

For further details of all experimental protocols please refer to the electronic supplementary material (ESM).

Human islet culture

Pancreatic human islets were obtained through the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (ESM Table 1). Human islets recovered after arrival in Connaught Medical Research Laboratories (CMRL) medium for 2 h, then were handpicked using a green gelatin filter to eliminate residual non-islet material. Human islets were treated with either a cytokine mixture (10 ng/ml TNF-α, 100 ng/ml IFN-γ and 5 ng/ml IL-1 β; all purchased from ProSpec, East Brunswick, NJ, USA) for 72 h, or glucolipotoxic (GLT) mixture (16.7–25 mmol/l glucose plus 0.5 mmol/l palmitate; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 48 h, in glucose-free RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) medium supplemented with 10% (vol./vol.) FBS (HyClone, South Logan, UT, USA) and 1% (vol./vol.) penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) for times indicated in the legends, prior to lysis for immunoblot analysis. mRNA was quantified from islets by quantified real-time PCR as described [16].

INS 832/13 cell culture, transient transfection and adenoviral transduction

INS 832/13 cells (gift from C. B. Newgard, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA) (passage 55–80) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium as described [17]. Cells were cultured under GLT conditions for 24 h, transfected with small interfering (si) RNA oligonucleotides (siPak1, cat no. S103082926; siCtrl, cat no. 1027310; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), or transduced by infection of adenovirus rat insulin promoter (AdRIP)-hPak1 or AdRIP-Ctrl (Viraquest, North Liberty, IA, USA) at multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 100, and subsequently treated with GLTor vehicle conditions (fatty acid-free BSA) for 2 h prior to harvest for immunoblot or cell death analyses. AdRIP-hPak1 was generated by insertion of the full-length hPak1 cDNA into the Ins2-adenoviral vector (gifted by T. Becker and C. B. Newgard, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA). Adenoviruses were packaged with EGFP to enable visualisation of infection efficiency (Viraquest).

Immunoblotting

Proteins were resolved on 10–12% SDS-PAGE for transfer to Standard PVDF, or polyvinylidene difluoride for LI-COR fluorescence imaging (PVDF/FL; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) membranes for immunoblotting using the following antibodies: Rabbit anti-PAK1, phospho extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK1/2T202/Y204), mouse anti-ERK1/2, B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), and cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), phospho Bcl2S70 and rabbit anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse anti-tubulin (Sigma); all used at 1:1000 dilutions. IRDye 680 RD goat anti-mouse and IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) antibodies were used at 1:15,000 dilutions, and goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad, Irvine, CA, USA) were used at 1:5000 dilutions. All antibodies were validated for specificity based upon predicted molecular weight of immunoreactive band, selective loss of signal using siRNA or gain of signal using overexpression, and blocking peptides. Immunoreactive bands were visualised with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)/Prime (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and imaged using a Chemi-Doc Touch (Bio-Rad). Phosphorylated and total ERK1/2 blots were imaged using the Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR).

Animals and diets

All animal procedures/protocols were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Pak1 KO mice are a classic whole-body gene-ablation model maintained on the C57BL/6J genetic background, generated in-house from breeders originating from Jonathan Chernoff (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA) [18]. After weaning (at 21 days of age), mice were allowed free access to water and standard chow (2018SX Teklad Global 18% Protein Extruded Rodent Diet, Harlan Laboratories, IN, USA). Mice were group housed until sorted into individual housing after the initial acclimatisation period and the start of the feeding study. All mice were housed under standard housing conditions using paper bedding, on a 12 hr light cycle (7:00 lights on, 19:00 lights off). Paired wild-type (WT) littermates served as controls. Male 6-week old WT and Pak1 KO mice were acclimated to commercially available low-fat diet (LFD, cat no. D01030107, Research Diets, Brunswick, NJ, USA), containing 10% energy from fat, for 2 weeks prior to starting the 45% energy from fat/palmitate-based ‘western’ diet (WD, cat no. D01030108, Research Diets); both pelleted diets.

Serum analytes, i.p. glucose tolerance testing and HOMA-IR

Mice were fasted for 6 h or 16 h prior to i.p. D-glucose (Sigma) injection (2 g/kg body weight) for measurements of serum insulin response and i.p. glucose tolerance tests (IPGTT), respectively. Glucose measurements were sampled from the tail vein using a Hemocue analyzer (Hemocue, Mission Viejo, CA, USA). Serum insulin was quantified using a sensitive rat insulin radio immunoassay kit (EMD Millipore). The homeostasis model for insulin resistance HOMA-IR was calculated according to Matthews et al [19].

Morphometric assessment of islet cell mass

Mouse islet morphometry was evaluated using anti-insulin immunohistochemical staining of pancreatic sections as previously described [20]. Percentage of beta cell area was calculated using AxioVision software version LE4.8 (www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en_us/downloads/axiovision; accessed 8 May 2014); beta cell mass was calculated by multiplying percentage of beta cell area with pancreas weight.

Proliferation and immunofluorescent confocal microscopy

Paraffin-embedded pancreatic tissue sections were prepared and assessed as previously described [21]. To assess proliferation, three pancreatic sections at least 100 μm apart were immunostained with rabbit anti-insulin (1: 500 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas TX, USA), rabbit antiphospho-Histone 3, Ser10 (pHH3) (1:500 dilution, EMD Millipore) and DAPI-stained (Sigma); pancreatic sections were taken from at least three mice per group. Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1: 500 dilution, Invitrogen) secondary antibody was used. Sections were scanned using a Nikon TiE inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). More than 2000 total insulin-positive cells were counted per pancreas. Results were expressed as the percentage of cells positive for all three stains relative to the total number of insulin-positive cells. Guinea pig anti-glucagon (1:500 dilution, EMD Millipore) was used for staining of alpha cells (ESM Fig. 1).

Cell death assay

Apoptosis was measured from INS 832/13 cells treated with GLT stress by assessment of DNA fragmentation and histone release from the nucleus using the Cell Death Detection ELISA Plus kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) [22]. Absorbance was measured at 405 and 490 nm from all samples in duplicate and cell death calculated as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made by two-tailed Student’s t test or ANOVA, using GraphPad Prism Version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

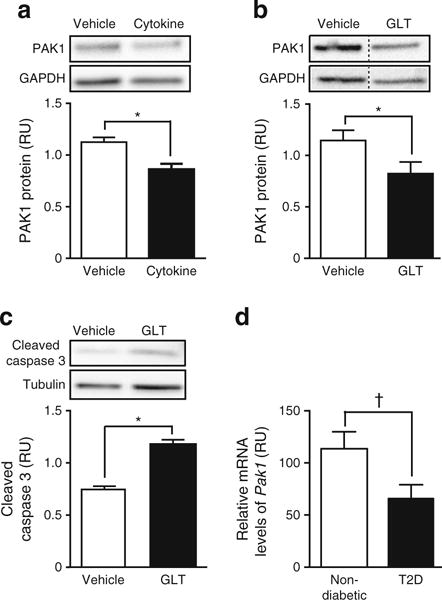

Human islets subjected to diabetogenic stressors exhibit reduced PAK1 protein expression

To determine whether the loss of PAK1 protein reported in type 2 diabetic human islets could be recapitulated in vitro with diabetogenic stressors, islets from non-diabetic human donors were subjected to pro-inflammatory cytokines or GLT conditions. Cytokine treatment decreased PAK1 protein abundance by 23% compared with vehicle-treated islets from the same donor (Fig. 1a). Cytokine action was validated by detection of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induction, a reporter of inflammatory stress in islets [23, 24] (data not shown). GLT stress decreased PAK1 by 28%, and significantly increased expression of cleaved caspase 3 (Fig. 1b,c). To obtain enough islets for these paired studies, islets from obese donors were also used (ESM Table 1), and all responded to the diabetogenic stimuli with reduced PAK1. Pak1 mRNA was reduced by 43% from type 2 diabetic islets compared with non-diabetic islets (Fig. 1d). These results indicate that diabetogenic stressors likely contribute to the apoptosis and attenuated PAK1 protein levels seen in type 2 diabetes human islets.

Fig. 1.

PAK1 levels are reduced concurrent with increased apoptosis in human islets subjected to diabetogenic stressors. Human islets were exposed to (a) pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNFα and IFNγ for 72 h; n = 4), or (b, c) GLT stress (glucose at 16.7 mmol/l [b], or 25 mmol/l [c] with 0.5 mmol/l palmitate for 48 h; n = 3). Proteins detected by immunoblotting were quantified relative to GAPDH or tubulin (relative units [RU]). (d) Pak1 mRNA levels in type 2 diabetes (T2D) vs non-diabetic donor islets (n = 4 sets each type of donor islets), relative to 18SrRNA. *p < 0.05; †p = 0.067

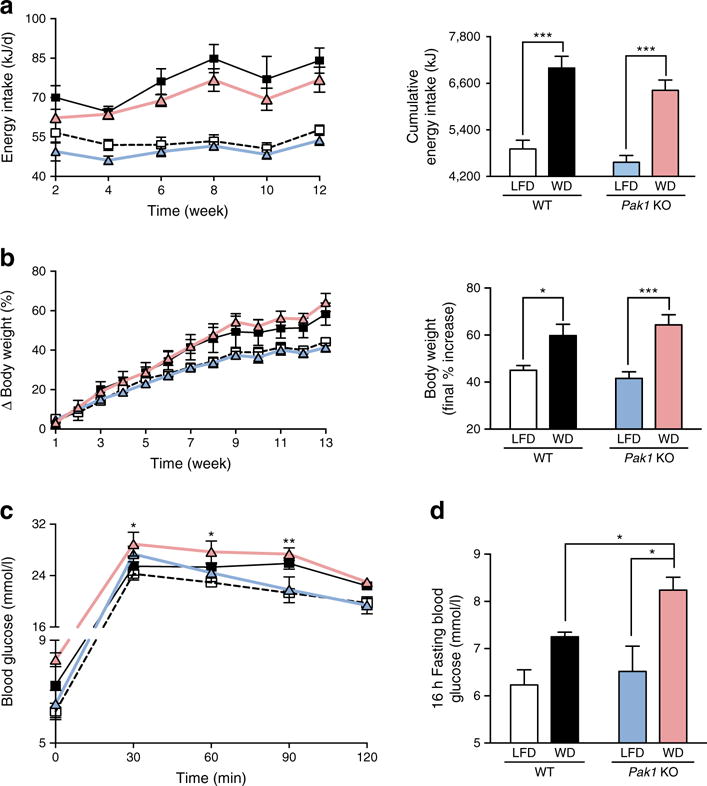

Pak1 KO mice fed WD exhibit fasting hyperglycaemia with insulin insufficiency

To first confirm that the WD-diet was obesogenic, food intake and body weight were monitored throughout the 13-week feeding period. Because of the inherent variability in source components for chow, we used a semi-purified, palmitate-based LFD. Although there was no difference in grams of food intake (data not shown), the WD-fed Pak1 KO and WT mice consumed significantly more energy daily and cumulatively (~40% more) than the LFD-fed mice (Fig. 2a). Accordingly, the WD-fed mice showed a larger per cent increase in body weight, with equivalent increases between Pak1 KO and WT mice (Fig. 2b). Adipose tissue was significantly increased in the WD-fed mice vs LFD-fed mice (Table 1). IPGTT after a 16 h fast showed the WD-fed Pak1 KO mice to have substantially elevated fasting blood glucose concentrations (Fig. 2c,d). LFD-fed mice were heavier and less glucose tolerant than expected, based upon comparisons with chow-fed mice. As our LFD-induced data were similar to another study using these diets [25], this appears to be a feature of the palmitate-containing LFD.

Fig. 2.

WD-fed Pak1 KO mice exhibit elevated fasting blood glucose. (a) Food intake (WT-LFD, n = 4; WT-WD, n = 3; Pak1 KO-LFD, n = 5; Pak1 KO-WD, n = 4). (b) Body weight (WT-LFD, n = 6; WT-WD, n = 4; Pak1 KO-LFD, n = 8; Pak1 KO-WD, n = 6). (c) IPGTT following 16 h fast (WT-LFD, n = 3; WT-WD, n = 3 Pak1 KO-LFD, n = 4; Pak1 KO-WD, n = 4; *p < 0.05 vs LFD). (d) 16 h fasting blood glucose after 10 weeks on WD or LFD. WT-LFD, white squares/bars; WT-WD, black squares/bars; Pak1 KO-LFD, blue triangles/bars; Pak1 KO-WD, red triangles/bars. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

Table 1.

Tissue weights (as % of total body weight)

| WT-LFD n = 6 |

WT-WD n = 4 |

Pak1 KO-LFD n = 6 |

Pak1 KO-WD n = 6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 34.7 ± 2 | 38.8 ± 2 | 33.9 ± 3 | 38.6 ± 1 |

| Tissue (% body weight) | ||||

| Pancreas | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 0.84 ± 0.04 |

| Spleen | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| Kidney | 0.67 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.07 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.59 ± 0.08 |

| Heart | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

| Lung | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.70 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.07 |

| Fat | 4.17 ± 0.34 | 5.90 ± 0.30a,b | 3.85 ± 0.59 | 5.22 ± 0.18c,d |

| Intestine | 1.41 ± 0.20 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 1.26 ± 0.19 | 1.27 ± 0.15 |

| Liver | 5.43 ± 0.52 | 4.57 ± 0.14b | 4.85 ± 0.31 | 4.60 ± 0.09d |

| Muscle | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.11 |

Data represent the average ± SEM

Weights were collected after 13 weeks of feeding the diets indicated, for determination of variables shown Statistically significant differences were detected by two-way ANOVA using a Tukey’s multiple comparison test

WT-WD vs Pak1 KO-LFD;

WT-WD vs WT-LFD;

Pak1 KO-WD vs Pak1 KO-LFD;

Pak1 KO-WD vs WT-LFD

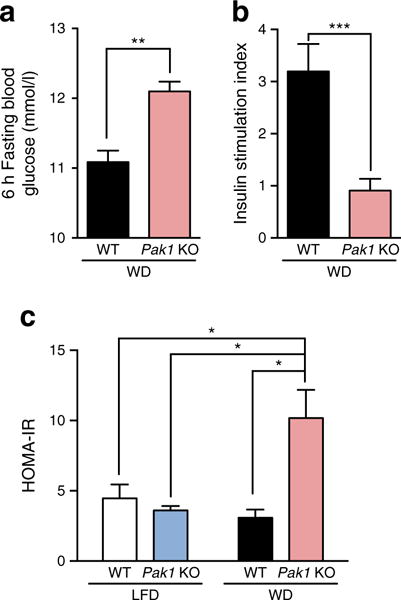

Consistently, after just a 6 h fasting period, WD-fed Pak1 KO mice again displayed elevated fasting blood glucose levels relative to that of WD-fed WT mice (Fig. 3a); the same WD-fed Pak1 KO mice also failed to show increased serum insulin levels upon glucose injection (index: glucose-stimulated/basal insulin levels) (Fig. 3b). By contrast, WD-fed WT mice mounted a substantial insulin response, as previously shown [26]. LFD-fed Pak1 KO or WT mice showed insulin responses similar to chow-fed WT mice (LFD-fed Pak1 KO 1.35 ± 0.15; LFD-fed WT 1.15 ± 0.11; chow-fed WT 1.26 ± 0.17), suggesting that the LFD-diet did not negatively impact islet responsiveness to glucose. WD-fed Pak1 KO mice show increased insulin resistance compared with WD-fed WT mice, as calculated by HOMA-IR (Fig. 3c). These phenotypic data suggest that the WD-fed Pak1 KO mice were unable to mount a sufficient insulin response to manage the elevated glucose load induced by WD-feeding.

Fig. 3.

WD-fed Pak1 KO mice exhibit fasting hyperglycaemia, impaired beta cell responsiveness, and elevated HOMA-IR. (a) Fasting blood glucose and (b) serum insulin (shown as stimulation index; glucose-stimulated/fasted insulin) were measured in 6 h fasted mice after 11 weeks on WD. Blood was collected prior to and 10 min following glucose injection to assess the stimulation index of responsiveness. (c) Insulin resistance, as determined by HOMA-IR [19]. Data represent the average ± SEM of 3–6 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

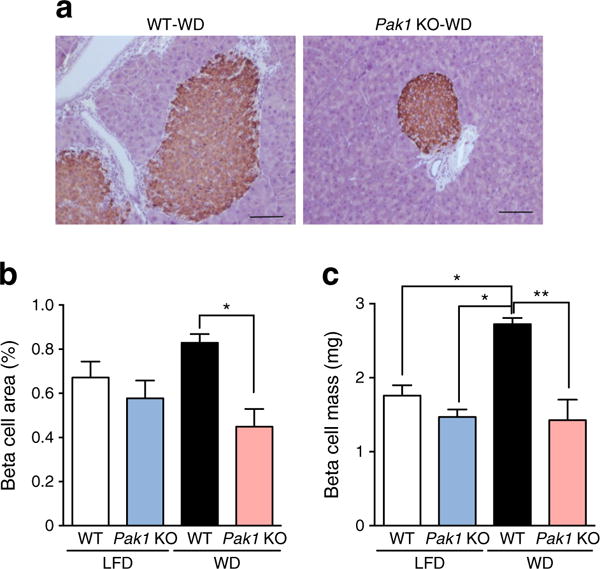

Pak1 KO mice show no WD-induced gain in beta cell mass

Given the insulin insufficiency seen in the WD-fed Pak1 KO sera, the corresponding pancreases were evaluated ex vivo for changes in beta cell mass relative to LFD- and WD-fed WT mice. WD-fed Pak1 KO islet beta cell area was visibly diminished relative to WD-fed WT mice (Fig. 4a). At ~0.83% beta cell area, the WD-fed WT beta cell area exceeded the 0.67% beta cell area of the LFD-fed WT mouse pancreas (Fig. 4b, n = 3 pancreases per group, p = 0.054). Beta cell area was reduced to ~0.45% in WD-fed Pak1 KO mouse islets (red bar), a significant 46% loss relative to the WD-fed WT mice. Calculating beta cell mass, which takes into account total pancreas weight, WD-fed Pak1 KO mice were 43% deficient, relative to WD-fed WT mass (Fig. 4c). Glucagon-staining was visibly similar among all groups (ESM Fig. 1). Thus, unlike the WT mice, the Pak1 KO mice showed no WD-induced gain in beta cell area or mass.

Fig. 4.

WD-fed Pak1 KO mice have decreased beta cell mass. (a) Whole pancreases were fixed and immunostained for insulin content (scale bar, 100 μm), from which (b) islet beta cell area and (c) islet beta cell mass were calculated. Bar graphs represent the average ± SEM for three pancreases per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Decreased beta cell replication in WD-fed Pak1 KO mice

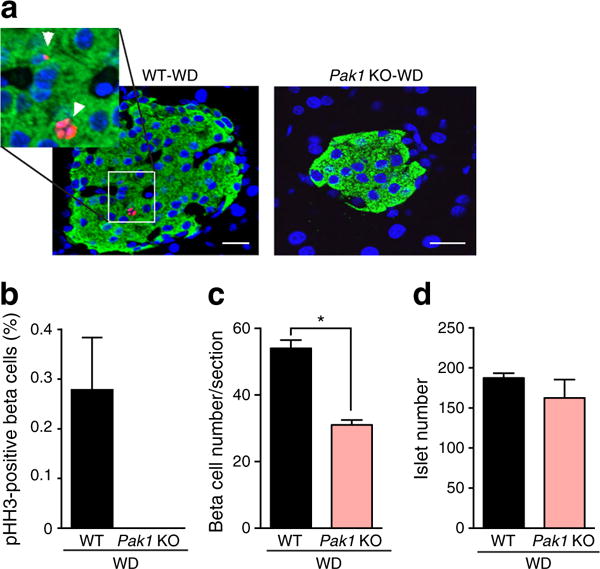

To determine if loss of beta cell mass in WD-fed Pak1 KO mice was related to defects in replication, pHH3 staining was evaluated [26]. While pHH3-stained cells were detected in insulin-stained islet cells from WD-fed WT mice, no pHH3-positive cells were seen in an equivalent number of beta cells from WD-fed Pak1 KO mice (Fig. 5a,b). Moreover, while WD-fed Pak1 KO mice had 35% fewer insulin-staining beta cells per islet (Fig. 5c), the number of islets was similar among all groups (Fig. 5d). These results suggest that PAK1 is required in the WD-induced beta cell replication.

Fig. 5.

WD-fed Pak1 KO mice have reduced beta cell replication. (a) Fixed pancreases were stained for insulin (green), pHH3 (red) and DAPI (blue); scale bar, 20 μm. (b) pHH3- and insulin-double-positive cells were normalised per total number of insulin-positive cells for each group. No pHH3-stained cells were detected in Pak1 KO pancreases; (c) average total number of insulin-positive cells per section; (d) total islet numbers quantified across >9 sections per group, with three mice per group. *p < 0.05

PAK1 deficiency exacerbates the effects of glucolipotoxicity upon beta cell demise

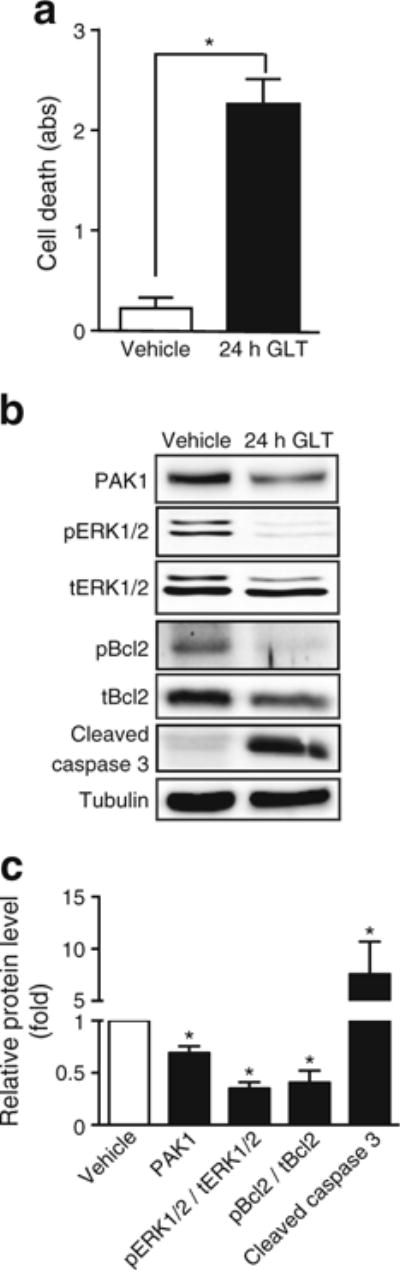

INS 832/13 cells were exposed to GLT stress as a means to interrogate the mechanism(s) underlying the beta cell mass differences in the mice. Prior reports of PAK1 signalling downstream to ERK were tested for involvement [4, 6]. After 24 h of GLT treatment, INS 832/13 cells exhibited substantial cell death, as determined by the presence of cytosolic nucleosomal fragments [22] (Fig. 6a), and a sevenfold increase in cleaved caspase 3 in GLT-treated cells (Fig. 6b). Concurrent with this, cells had 30% less PAK1 protein, and >60% reductions in phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), a downstream target of PAK1 in beta cells, and pBcl2, an anti-apoptotic factor (Fig. 6b). These results suggest links between PAK1 abundance and ERK1/2 and Bcl2 signalling in GLT-induced beta cell stress.

Fig. 6.

Chronic GLT-induced stress reduces PAK1 abundance concurrent with reduced ERK and Bcl2 phosphorylation. INS 832/13 cells were subjected to GLT for 24 h and (a) cell death was determined by ELISA. (b) Resultant lysates were assessed for PAK1 content, phosphorylated (p) and total (t) forms of ERK and Bcl2, and cleaved caspase 3 by immunoblot quantification. The bar graph represents the average ± SEM, with vehicle-treated lysate bands in each of five independent cell passage experiments set equal to 1 and GLT-treated protein levels normalised thereto. *p < 0.05

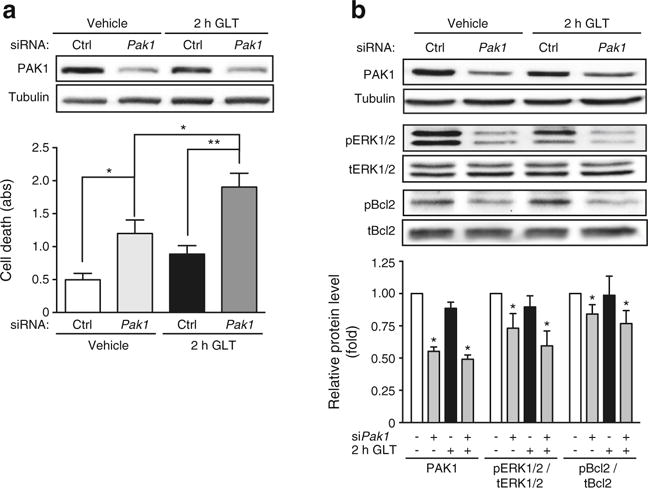

To determine whether PAK1 depletion exacerbates the effects of GLT upon apoptosis, perhaps in an additive manner, the GLT exposure time was limited to just 2 h in cells transfected with scrambled (Ctrl) or Pak1 siRNAs. GLT exposure for just 2 h did not significantly reduce PAK1 protein levels, permitting separation of GLT effects from PAK1 depletion. The combined effect of Pak1 siRNA with 2 h GLT stress exerted a significant increase in cell death over that of depletion or GLT stress alone (Fig. 7a). PAK1 depletion resulted in reduced levels of pERK1/2 and pBcl2 (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Combined effects of PAK1 depletion and acute glucolipotoxicity upon beta cell death. INS 832/13 cells transfected with Pak1 siRNA or control (Ctrl) siRNA were incubated for 46 h prior to GLT exposure for 2 h and (a) cell death was determined by ELISA (n = 5–6; abs, absorbance). (b) Resultant lysates were assessed for PAK1 content and phosphorylated (p) and total (t) forms of ERK and Bcl2. The bar graphs represent the average ± SEM, with siCtrl/vehicle-treated lysate bands in each of three independent cell passage experiments set equal to 1 and remaining treatment group protein levels normalised thereto. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

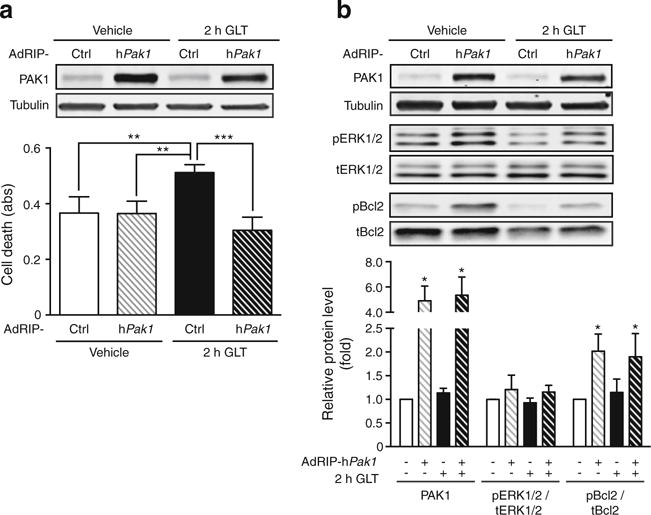

Consistent with a role in cell survival/anti-apoptosis, PAK1 overexpression protected cells from GLT-induced cell death (Fig. 8a). PAK1 overexpression increased pERK1/2 levels only slightly (Fig. 8b), perhaps suggesting that ERK1/2 phosphorylation was maximised under our serum-containing cell culture conditions (serum contains growth factors that activate ERK1/2). PAK1 overexpression significantly increased levels of phosphorylated Bcl2.

Fig. 8.

PAK1 overexpression protects against acute GLT-induced cell death. INS 832/13 cells were transduced to overexpress human PAK1 using AdRIP-hPAK1 or AdRIP-Ctrl for 46 h prior to GLT exposure for 2 h and (a) cell death was determined by ELISA (n = 3; abs, absorbance). (b) Resultant lysates were assessed for PAK1 content, phosphorylated (p) and total (t) forms of ERK and Bcl2 by immunoblot quantification. The bar graph represents the average ± SEM, with AdRIP-hPak1/vehicle-treated lysate bands in each of three independent cell passage experiments set equal to 1 and remaining treatment group protein levels normalised thereto. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Discussion

In this report we demonstrate that increased PAK1 abundance can protect beta cells against GLT-induced cell death, and that this is linked through phosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl2. Our studies suggest that in the islet beta cell, chronic exposure to GLT stress impairs PAK1 abundance, coordinate with attenuated ERK and Bcl2 signalling, and increased cell death. In human islets, chronic GLT stress also reduced PAK1 protein and increased cleaved caspase 3 expression. Modelling GLT stress in vivo, Pak1 KO mice fed a palmitate-rich western diet (WD-fed Pak1 KO) displayed significant fasting hyperglycaemia and loss of beta cell mass in just 10 weeks. As such, PAK1 deficiency may underlie an increased diabetic susceptibility.

Since the islets of the WD-fed Pak1 KO mice also had decreased beta cell proliferation relative to WD-fed WT mice, PAK1 may play multiple roles in the process of beta cell mass expansion. The apparent additivity of short-term/acute GLT stress with PAK1 knockdown could suggest that GLT induces an early PAK1-independent signal that is insufficient to evoke cell death; since PAK1 levels are un-impacted by this, the anti-apoptotic mechanism is maintained. Indeed, acute GLT treatment impacts KATP and Ca2+ channel functions in beta cells without inducing apoptosis [27, 28]. However, once GLT exposure is prolonged, then PAK1 is decreased, and ERK1/2 and Bcl2 are left unchecked to allow apoptosis. Beyond the beta cell, PAK1 has been demonstrated to downregulate additional pro-apoptotic factors, such as forkhead box in rhabdomyosarcoma (FKHR; also known as forkhead box O1 [FOXO1]) and Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (BimL) [29–31]. Given the possibility that apoptosis effects in clonal beta cells may not fully account for the differences in mouse beta cell mass observed, beta cell replication was also evaluated, using mouse pancreases. Our data indicated that PAK1 may be important for beta cell replication and survival. Indeed, PAK1 is known to participate in cell cycle progression and mitosis via regulating various effectors, such as Aurora-A [32], Polo-like kinase 1 [33] and cyclin-D1 [34] in other cell types.

Chronically elevated levels of NEFA, principally saturated fatty acids, exert deleterious effects on islet beta cells. In vitro, saturated NEFA such as palmitate increase basal insulin secretion, decrease glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [35–37] and increase beta cell death [22, 38, 39]. Palmitate causes these detrimental effects through multiple mechanisms, such as increasing reactive oxygen species, ceramide, and excessive nitric oxide production, as well as activation of ER stress pathways [40, 41]. In vivo, healthy beta cells have the capability to adapt to elevated serum NEFA levels through mechanisms that are not completely understood. However, in genetically pre-disposed beta cells, glucolipotoxicity eventually results in beta cell decompensation and dysfunction and ultimately beta cell failure [42, 43]; our findings support the concept that PAK1 depletion represents a new type of genetic predisposition. The importance of PAK1 in maintaining functional beta cell mass during dietary stress becomes clinically relevant when considering that PAK1 protein levels in type 2 diabetic human islets are reduced by ~80% compared with non-diabetic controls [4] and that the human Pak1 gene is located in the type 2 diabetes susceptibility locus on Chromosome 11 [44, 45]. While much more needs to be known to determine whether Pak1 actually confers the diabetes risk at this site and whether the diabetes risk allele even results in decreased PAK1 expression, Pak1 mRNA was reduced by 43% in type 2 diabetic compared with non-diabetic and non-obese donor islets. The most appropriate way to determine whether Pak1 confers diabetes risk at the sites mentioned may be to examine Pak1 mRNA and protein in islets from donors (low BMI, obese and type 2 diabetic) known to carry the risk allele.

The palmitate-based diet was chosen to mimic the palmitate-rich fast-food diet prevalent in western society. This revealed that WD-fed WT could maintain the glucose tolerance profile of the LFD-fed WT mice through upregulation of their functional beta cell mass (increased insulin release and beta cell expansion). However, that the blood glucose levels remained >16.65 mmol/l at 2 h after glucose injection is reminiscent of a peripheral insulin resistant phenotype, suggesting that the palmitate-enriched LFD-diet may have generally impacted glucose homeostasis. This concept is supported by prior analyses of WT vs Pak1 KO mice fed standard chow, wherein WT mice were glucose tolerant and the Pak1 KO mice were intolerant [4, 5]. Moreover, in the current study, LFD-fed WT and Pak1 KO mice weighed 20% more than age-matched chow-fed mice after just 13 weeks of feeding (p < 0.05), suggesting that the palmitate-based fat source prompted obesity and insulin resistance. Therefore, while on the LFD-diet, it is possible that insulin resistance and subsequent glucose intolerance induced by increased weight-gain alone masked the underlying defects arising from the PAK1 deficiency.

In this whole-body Pak1 KO model, input from tissues/organs beyond the islet beta cell may have contributed to the fasting hyperglycaemia and glucose intolerance of the WD-fed Pak1 KO mice. For example, in skeletal muscle PAK1 is required for the translocation of GLUT4 vesicles to the plasma membrane to facilitate glucose clearance, and chow-fed Pak1 KO mice have been shown to display defects in this process [4]. Additionally, a defect in GLP-1 production and secretion has been reported both in Pak1 KO mice [5, 46] and PAK1-depleted GLP-1-secreting L cells [47]. As GLP-1 is involved in enhancing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, increasing insulin biosynthesis, and promoting maintenance of beta cell mass [48, 49], as well as processes external to beta cell [50, 51], it is possible that depressed GLP-1 secretion/signalling is contributing to the severe glucose intolerant phenotype of the WD-fed Pak1 KO mice. Along these same lines, it has been reported that activation of the GLP-1R-signalling pathway in the liver rescues the impaired pyruvate tolerance observed in aged Pak1 KO mice [46]. Clarifying the role of PAK1 in the process of beta cell compensatory mechanisms will thus require the study of beta cell-specific Pak1 KO mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated the requirement of PAK1 in the adaptation of the beta cell to the metabolic stress of a palmitate-rich western-style diet. These studies additionally suggest that inflammatory- or GLT-stressors carry the capacity to reduce PAK1 protein levels in human islets. PAK1 may be a critical factor to target as a means to rescue/enhance beta cell mass in response to the stresses encountered during the development of pre- and type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Elmendorf and S. Gunst (Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, Indiana University School of Medicine, USA) for providing the animal diets and the human PAK1 cDNA, respectively, and to C. Newgard and T. Becker (Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, Duke University, USA) for the gift of the Ins2-adenoviral vector. We thank P. Fueger (Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, Indiana University School of Medicine, USA) and R. Veluthakal (Department of Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology, City of Hope Beckman Research Institute, USA) for their helpful critiques of this manuscript. We are also indebted to technical assistance from J. Lu, D. Morris, E. Sims and S. Tersey, as well as A. Aslamy and E. Bolanis (Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, Indiana University School of Medicine, USA).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (F32 DK094488 to SMY; CTSI-KL2 RR025760 to ZW; and DK067912, DK076614 and DK102233 to DCT) and American Heart Association (12PRE11890042 to LR).

Abbreviations

- AdRIP

Adenovirus rat insulin promoter

- Bcl2

B cell lymphoma 2

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

Extracellular signal-related kinase

- GLT

Glucolipotoxicity

- IPGTT

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- KO

Knockout

- LFD

Palmitate-based low-fat diet

- PAK1

p21 protein (Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase 1

- pHH3

Phospho-Histone H3

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- WD

45% energy from fat/palmitate-based ‘western diet’

- WT

Wild-type

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-016-4042-0) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author contributions

MA and SMY designed the study, acquired and analysed data, drafted the manuscript and approved its final version. ZW participated in the design of the in vivo experiments, acquired and analysed in vivo data, and revised the manuscript’s intellectual content and approved its final version. EO acquired the islet morphometry experiments, drafted the morphometry part of manuscript and approved the final version. LR and RT analysed and interpreted serum analyte data, drafted this part, and approved its final version. DCT contributed to the design and interpretation of data, revised the article for important intellectual content, and approved the final version. DCT, MA and SMY are responsible for the integrity of this work. SMY is now at Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. ZW is now at National University of Health Sciences, Lombard, IL, USA. LR is now at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA.

References

- 1.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wajchenberg BL. Clinical approaches to preserve beta-cell function in diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:515–535. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier JJ, Breuer TG, Bonadonna RC, et al. Pancreatic diabetes manifests when beta cell area declines by approximately 65% in humans. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1346–1354. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2466-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Oh E, Clapp DW, Chernoff J, Thurmond DC. Inhibition or ablation of p21-activated kinase (PAK1) disrupts glucose homeostatic mechanisms in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41359–41367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.291500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang YA, Shao W, Xu XX, Chernoff J, Jin T. P21-activated protein kinase 1 (Pak1) mediates the cross talk between insulin and beta-catenin on proglucagon gene expression and its ablation affects glucose homeostasis in male C57BL/6 mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:77–88. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalwat MA, Yoder SM, Wang Z, Thurmond DC. A p21-activated kinase (PAK1) signaling cascade coordinately regulates F-actin remodeling and insulin granule exocytosis in pancreatic beta cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Thurmond DC. PAK1 limits the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein bad in pancreatic islet β-cells. FEBS Open Bio. 2012;2:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YC, Fueger PT, Wang Z. Depletion of PAK1 enhances ubiquitin-mediated survivin degradation in pancreatic beta-cells. Islets. 2013;5:22–28. doi: 10.4161/isl.24029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraegen EW, James DE, Storlien LH, Burleigh KM, Chisholm DJ. In vivo insulin resistance in individual peripheral insulin resistance of the high fat fed rat: assessment by euglycemic clamp plus deoxyglucose administration. Diabetologia. 1986;29:192–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02427092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocchini AP, Marker P, Cervenka T. Time course of insulin resistance associated with feeding dogs a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E147–E154. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.1.E147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winzell MS, Ahren B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: a model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S215–S219. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hull RL, Kodama K, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Prigeon RL, Kahn SE. Dietary-fat-induced obesity in mice results in beta cell hyperplasia but not increased insulin release: evidence for specificity of impaired beta cell adaptation. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1350–1358. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trajkovski M, Mziaut H, Schubert S, Kalaidzidis Y, Altkruger A, Solimena M. Regulation of insulin granule turnover in pancreatic beta-cells by cleaved ICA512. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33719–33729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804928200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eguchi K, Manabe I, Oishi-Tanaka Y, et al. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link beta cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell Metab. 2012;15:518–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin N, Chen H, Zhang H, Wan X, Su Q. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibition ameliorates palmitate-induced INS-1 beta cell death. Endocrine. 2012;42:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9633-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramalingam L, Oh E, Yoder SM, et al. Doc2b is a key effector of insulin secretion and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2012;61:2424–2432. doi: 10.2337/db11-1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen JD, Jaffer ZM, Park SJ, et al. p21-activated kinase regulates mast cell degranulation via effects on calcium mobilization and cytoskeletal dynamics. Blood. 2009;113:2695–2705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-160861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maier B, Ogihara T, Trace AP, et al. The unique hypusine modification of eIF5A promotes islet beta cell inflammation and dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2156–2170. doi: 10.1172/JCI38924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh E, Kalwat MA, Kim MJ, Verhage M, Thurmond DC. Munc18-1 regulates first-phase insulin release by promoting granule docking to multiple syntaxin isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25821–25833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.361501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai E, Bikopoulos G, Wheeler MB, Rozakis-Adcock M, Volchuk A. Differential activation of ER stress and apoptosis in response to chronically elevated free fatty acids in pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E540–E550. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00478.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eizirik DL, Sammeth M, Bouckenooghe T, et al. The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: expression of candidate genes for type 1 diabetes and the impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbett JA, Mikhael A, Shimizu J, et al. Nitric oxide production in islets from nonobese diabetic mice: aminoguanidine-sensitive and -resistant stages in the immunological diabetic process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8992–8995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambery AG, Tackett L, Penque BA, Hickman DL, Elmendorf JS. Effect of Corncob bedding on feed conversion efficiency in a high-fat diet-induced prediabetic model in C57Bl/6J mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2014;53:449–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sims EK, Hatanaka M, Morris DL, et al. Divergent compensatory responses to high-fat diet between C57BL6/J and C57BLKS/J inbred mouse strains. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1495–E1511. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson O, Deeney JT, Branstrom R, Berggren PO, Corkey BE. Activation of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel by long chain acyl-CoA. A role in modulation of pancreatic beta-cell glucose sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10623–10626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y, Sharp GW, Straub SG. The inhibitors of protein acylation, cerulenin and tunicamycin, increase voltage-dependent Ca(2+) currents in the insulin-secreting INS 832/13 cell. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schurmann A, Mooney AF, Sanders LC, et al. p21-activated kinase 1 phosphorylates the death agonist bad and protects cells from apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:453–461. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.453-461.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazumdar A, Kumar R. Estrogen regulation of Pak1 and FKHR pathways in breast cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2003;535:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Yang Z, et al. Dynein light chain 1, a p21-activated kinase 1-interacting substrate, promotes cancerous phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao ZS, Lim JP, Ng YW, Lim L, Manser E. The GIT-associated kinase PAK targets to the centrosome and regulates Aurora-A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maroto B, Ye MB, von Lohneysen K, Schnelzer A, Knaus UG. P21-activated kinase is required for mitotic progression and regulates Plk1. Oncogene. 2008;27:4900–4908. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balasenthil S, Sahin AA, Barnes CJ, et al. p21-activated kinase-1 signaling mediates cyclin D1 expression in mammary epithelial and cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1422–1428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elks ML. Chronic perifusion of rat islets with palmitate suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin release. Endocrinology. 1993;133:208–214. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.1.8319569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou YP, Grill VE. Long-term exposure of rat pancreatic islets to fatty acids inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion and biosynthesis through a glucose fatty acid cycle. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:870–876. doi: 10.1172/JCI117042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubois M, Kerr-Conte J, Gmyr V, et al. Non-esterified fatty acids are deleterious for human pancreatic islet function at physiological glucose concentration. Diabetologia. 2004;47:463–469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maedler K, Spinas GA, Dyntar D, Moritz W, Kaiser N, Donath MY. Distinct effects of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids on beta-cell turnover and function. Diabetes. 2001;50:69–76. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot ML, et al. Saturated fatty acids synergize with elevated glucose to cause pancreatic beta-cell death. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4154–4163. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlsson C, Borg LA, Welsh N. Sodium palmitate induces partial mitochondrial uncoupling and reactive oxygen species in rat pancreatic islets in vitro. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3422–3428. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lupi R, Dotta F, Marselli L, et al. Prolonged exposure to free fatty acids has cytostatic and pro-apoptotic effects on human pancreatic islets: evidence that beta-cell death is caspase mediated, partially dependent on ceramide pathway, and Bcl-2 regulated. Diabetes. 2002;51:1437–1442. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poitout V, Robertson RP. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocrine Rev. 2008;29:351–366. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giacca A, Xiao C, Oprescu AI, Carpentier AC, Lewis GF. Lipid-induced pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction: focus on in vivo studies. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E255–E262. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00416.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silander K, Scott LJ, Valle TT, et al. A large set of Finnish affected sibling pair families with type 2 diabetes suggests susceptibility loci on chromosomes 6, 11, and 14. Diabetes. 2004;53:821–829. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer ND, Langefeld CD, Campbell JK, et al. Genetic mapping of disposition index and acute insulin response loci on chromosome 11q. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) family study. Diabetes. 2006;55:911–918. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiang YT, Ip W, Shao W, Song ZE, Chernoff J, Jin T. Activation of cyclic AMP signaling attenuates impaired hepatic glucose disposal in aged male p21- activated protein kinase-1 knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155:2122–2132. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim GE, Xu M, Sun J, Jin T, Brubaker PL. The Rho Guanosine 5′-triphosphatase, cell division cycle 42, is required for insulin-induced actin remodeling and glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in the intestinal endocrine l cell. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5249–5261. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mojsov S, Weir GC, Habener JF. Insulinotropin: glucagon-like peptide I (7–37) co-encoded in the glucagon gene is a potent stimulator of insulin release in the perfused rat pancreas. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:616–619. doi: 10.1172/JCI112855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Egan JM, Bulotta A, Hui H, Perfetti R. GLP-1 receptor agonists are growth and differentiation factors for pancreatic islet beta cells. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19:115–123. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turton MD, O’Shea D, Gunn I, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 1996;379:69–72. doi: 10.1038/379069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maljaars PW, Peters HP, Mela DJ, Masclee AA. Ileal brake: a sensible food target for appetite control. A review. Physiol Behav. 2008;95:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.