Abstract

The axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) has long been the subject of biological research, primarily owing to its outstanding regenerative capabilities. However, the gene expression programs governing its embryonic development are particularly underexplored, especially when compared to other amphibian model species. Therefore, we performed whole transcriptome polyA+ RNA sequencing experiments on 17 stages of embryonic development. As the axolotl genome is unsequenced and its gene annotation is incomplete, we built de novo transcriptome assemblies for each stage and garnered functional annotation by comparing expressed contigs with known genes in other organisms. In evaluating the number of differentially expressed genes over time, we identify three waves of substantial transcriptome upheaval each followed by a period of relative transcriptome stability. The first wave of upheaval is between the one and two cell stage. We show that the number of differentially expressed genes per unit time is higher between the one and two cell stage than it is across the mid-blastula transition (MBT), the period of zygotic genome activation. We use total RNA sequencing to demonstrate that the vast majority of genes with increasing polyA+ signal between the one and two cell stage result from polyadenylation rather than de novo transcription. The first stable phase begins after the two cell stage and continues until the mid-blastula transition, corresponding with the pre-MBT phase of transcriptional quiescence in amphibian development. Following this is a peak of differential gene expression corresponding with the activation of the zygotic genome and a phase of transcriptomic stability from stages 9 to 11. We observe a third wave of transcriptomic change between stages 11 and 14, followed by a final stable period. The last two stable phases have not been documented in amphibians previously and correspond to times of major morphogenic change in the axolotl embryo: gastrulation and neurulation. These results yield new insights into global gene expression during early stages of amphibian embryogenesis and will help to further develop the axolotl as a model species for developmental and regenerative biology.

Keywords: axolotl, development, transcriptome

1. Introduction

The Mexican axolotl salamander (Ambystoma mexicanum) has been the subject of biological inquiry for over 150 years (Dinsmore, 1991; Reiss et al., 2015), largely owing to its regenerative capacity (Nye et al., 2003). Among vertebrates, the axolotl is exceptional in its ability to regenerate numerous diverse body parts following injury, including limbs, tail, and heart (Tsonis, 2000). Furthermore, the axolotl also possesses a variety of features that make it appealing for developmental biology research: relatively facile reproduction, abundant offspring (up to 500 per breeding), and large embryo size (approximately 2mm diameter) (Khattak et al., 2014).

Many publications have demonstrated the deep insights that can be acquired from the application of transcriptomics to the study of early stages of development. Microarray experiments in Xenopus laevis identified phases of development by examining the transcript composition over discrete stages (Baldessari et al., 2005). Studies comparing the gene expression patterns underlying embryogenesis in both Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis show that despite variation in early stages of development, later developmental stages converge on very similar expression programs (Yanai et al., 2011). Additional work in Xenopus tropicalis exposed a number of novel splice variants present in embryogenesis (Tan et al., 2013). Fine-scale sampling led to the discovery of distinct waves of maternal transcript polyadenylation followed by early (stage 7) zygotic transcription, providing further details into the precise mechanism by which embryos undergo this critical maternal to zygotic transition (MZT) (Collart et al., 2014). A set of ultra-high temporal resolution RNA-Seq experiments over Xenopus tropicalis development provided exquisite resolution of transcriptome kinetics, measurement of absolute transcript copy numbers, and a predictive framework for determining common gene function (Owens et al., 2016). Work in Xenopus laevis identified genes important for mesoderm formation transcribed prior to the midblastula transition (MBT) (Skirkanich et al., 2011). Studies in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) model found thousands of maternal genes present prior to the MZT and demonstrated the critical importance of the transcription factors Nanog, Pou5f1, and SoxB1 in the activation of zygotic transcription (Aanes et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013; Leichsenring et al., 2013; Vesterlund et al., 2011). Work investigating the later morphogenic stages of embryonic development, such as gastrulation and neurulation in Xenopus tropicalis, revealed that these periods are also accompanied by dramatic transcriptional changes (Paranjpe et al., 2013). Recognizing that the terms MZT and MBT are often used interchangeably throughout the literature, and that MZT represents the broad temporal range over which maternal transcripts are degraded and zygotic transcription initiates in all vertebrates (Tadros and Lipshitz, 2009), we will hereafter use the traditional amphibian MBT nomenclature (Newport and Kirschner, 1982a) to refer to the time point at which we believe widespread zygotic transcription begins in earnest in the axolotl.

The use of the axolotl in developmental biology research lags its amphibian model organism relatives largely due to challenges in the sequencing and assembly of its genome. Most recent estimates put the diploid axolotl genome in the 32 GB range (Keinath et al., 2015), exceeding even the current record holder for the largest assembled genome, the Loblolly Pine (22 GB) (Neale et al., 2014). Additionally, the axolotl genome contains genes approximately five times larger and introns approximately ten times larger than those found in the human genome, further complicating the assembly process (Smith et al., 2009). Some recent success has been attained in characterizing regions of the enormous axolotl genome through the process of laser capture chromosome sequencing. This recent analysis suggests that approximately 19 GB of the axolotl sequence is single copy and 40% is repetitive. (Keinath et al., 2015). However, a fully assembled and well annotated genome remains computationally costly and is likely years away. To address these challenges, we developed a comparative analysis pipeline to match axolotl RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data to contigs in axolotl de novo transcriptome assemblies. We then inferred annotation of expressed axolotl transcripts by comparing expressed axolotl contigs to the well-annotated human transcriptome. By employing these methods, we previously identified patterns of gene expression present in regenerating axolotl limb tissue (Stewart et al., 2013).

Here, we used RNA-seq and our comparative analysis pipeline to investigate the gene expression that underlies embryonic development in axolotls. We uncovered a pattern of peaks of concentrated transcriptomic dynamism followed by intervals of relative stability. Comparison to published Xenopus tropicalis developmental transcriptome data reveals similarities in expression profiles between the axolotl and Xenopus lending support to the validity of our comparative analysis method. In addition, we also verified that our comparative analysis method works with annotation sets besides the human gene set by matching our axolotl data to the Xenopus tropicalis gene set and obtain similar results. These data and analyses will serve as an extensive resource for axolotl researchers while also providing insight into the evolution and conservation of the global gene expression profiles that govern embryonic development across species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Axolotl developmental stages and samples

All animal care was carried out in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The animals were housed in 40% Holtfreter’s salts, at 17°C with a pH range of 7.0–7.4. To perform matings, we co-housed male-female non-sibling pairs overnight and provided additional enrichment in the form of flat stones and plastic leaves. Following a successful breeding, we de-jellied and collected embryos over the course of development. We gathered embryos based upon morphological staging criteria set out in (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979) from a single breeding in triplicate at the following stages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 19, 24, 40, except for stages 1 and 11 when two embryos were collected. Here, we treat the axolotl stages as synonyms of the Xenopus developmental stages (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1956) based on morphological similarity.

As a result of the overnight fertilization, it was impossible to precisely determine the number of hours post fertilization (HPF) for each sample. Thus, in order to determine relative rates of change of the transcriptome over time, we incorporated data from (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979) as a relative time measurement, abbreviated BD_HPF. Analogously, the time between stages is measured in hours using Bordzilovskaya and Detlaff’s information (BD_Hour). Henceforth, we will report HPF as BD_HPF and time between stages as BD_Hours, keeping in mind that these measures and derivatives - such as the number of differentially expressed genes over time (DEGs/BD_Hour) are relative measures.

Upon collection, each embryo was placed into RNA Later (Qiagen), preserving them until all could be processed in parallel. Each sample was comprised of a single embryo. Samples were homogenized with a Fisher Power Gen 125 tissue homogenizer. We then extracted total RNA from homogenized samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The concentration of RNA was determined using the Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific), and the integrity of the samples was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

2.2 RNA sequencing

Samples were prepared via the Illumina TruSeq RNA protocol. In short, the RNA was thawed on ice and 50ul of sample was transferred to a 96 well plate. PolyA+ selection was undertaken via RNA purification beads followed by fragmentation for 6 minutes. Next, we performed first and second strand cDNA synthesis and purified with Agencourt AMPure XP beads. We then performed an end repair step. Next, we adenylated the 3′ ends, ligated Illumina adapters and purified the libraries with AMPure XP beads. Then, we performed cDNA enrichment via PCR (15 cycles). Finally, we validated our libraries via PicoGreen quantification on a Synergy plate reader. Samples were then pooled (six per lane) and sequenced with 2 × 101bp paired end reads on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 with TruSeq v3 chemistry.

For total RNA experiments, samples were prepared with the Illumina ScriptSeq Complete Kit. First, we removed rRNA using the Ribo-Zero Magnetic Kit. Next, we fragmented RNA for 5 minutes and synthesized cDNA. We then terminal tagged the cDNA, purified with Agencourt AMPure XP beads. Then, we performed cDNA enrichment via PCR (15 cycles) and purified the libraries with AMPure XP beads. Finally, we validated our libraries via PicoGreen quantification on a Synergy plate reader. Samples were then pooled and sequenced with 72bp reads with the Illumina HiSeq Rapid chemistry.

The raw read data and annotated gene expression measures are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE78034).

2.3 RNA-seq data analysis

The RNA-seq data consisted of three biological replicate samples from each stage (with the exception of stages 1 and 11, which only had two replicates), for a total of 49 samples. RNA-seq data were comprised of paired-end reads with a length of 101 bases (polyA+ data) and single end reads with a length of 72 bases (total RNA data). Adapter sequences were trimmed from reads using an in-house script (available at www.axolomics.org/default/files/ffq.ts.pe.ao.pl.tgz). Approximately 0.25% of reads were discarded for having fewer than 28 bases after adapter trimming. No other quality filters were applied. After filtering, the mean number of sequenced read pairs per sample was ~31.5 million. For each stage, the filtered reads from all replicates of that stage were combined and assembled using Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011) (v2014-04-13p1, with parameters “--glue_factor 0.01 --min_iso_ratio 0.1”). We chose not to build one single assembly using contigs from all stages because of computational memory limitations and concerns about creating “in-silico” transcript isoforms uniting contigs from different developmental stages. After building the stage-specific assemblies, a single combined non-redundant transcriptome assembly was created by clustering all contigs from all stage assemblies using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010) (v7.0.1090, with parameters “-cluster_smallmem -id 0.95 -strand both”) and only selecting the “centroid” contig from each cluster. The resulting assembly had 896,365 contigs.

Quantification of each RNA-seq sample was then performed using RSEM v1.1.6 (Li and Dewey, 2011) using the combined transcriptome assembly as the reference database. RSEM was run with the default options for paired-end data except for the “--no-polyA” option, which was used because the assembled contigs were not guaranteed to include polyA+ tails. By default, RSEM uses the Bowtie aligner (Langmead et al., 2009) to map the reads against the contigs and we had Bowtie v0.12.1 installed for this purpose. RSEM employs an expectation maximization algorithm, so that for reads that match to multiple contigs, RSEM assigns a fraction of each read to each contig based on estimated abundances of contigs based on unique reads (Li and Dewey, 2011).

To enable functional interpretation of the resulting transcriptional profiles for the combined axolotl transcriptome assembly, we used a comparative RNA-seq approach developed previously for analysis of axolotl RNA-seq data (Stewart et al., 2013). Briefly, the contigs of the combined assembly were first mapped to transcripts from another species by running BLAST (NCBI BLAST v2.2.18) with either the RefSeq RNA (via BLASTN), or protein (via BLASTX) sequences for that species as the database and each contig as a query. Contigs were assigned to transcripts by taking the best BLAST hit with E-value < 10−5. For each sample, the expected fragment counts for each contig (as computed by RSEM), were then converted to comparative transcript counts by summing the fragment counts of contigs mapped to the same transcript. Similarly, gene-level counts were obtained by summing the fragment counts of transcripts that were annotated with the same gene symbol. Thus, if two contigs map to different isoforms of the same human gene or two contigs representing two axolotl in-paralogs map to the same human gene, their counts will be combined into the count for one human gene. Relative abundances, in terms of transcripts per million (TPM), for genes were computed by first normalizing each gene’s fragment count by the sum of the “effective lengths” (length less the read length) of the contigs mapped to that gene and then scaling the resulting values such that they summed to one million over all genes. Contigs mapping to rRNA transcripts and their respective counts were removed from the analysis. The list of assembled and annotated contigs is available at www.axolomics.org//sites/default/files/AxoDevelTimecourse_Annotated_Contigs_with_Gene_Symbol.fa.tgz. This comparative approach was run using both human and Xenopus tropicalis as reference species. The NCBI RefSeq sets used for human and X. tropicalis were dated 12/7/2009 and 8/3/2015, respectively. It should be noted that by virtue of matching to human (or frog) annotation there will be axolotl-specific genes that our methodology a priori cannot capture.

We also estimated gene specific within-condition mean and variance using median-by-ratio normalized expected counts (normalized ECs) (Leng et al., 2013) of samples within each of the 17 stages. For each stage, the global mean-variance relationship is represented by a fitted curve using all estimates in this stage. The curve was fitted using polynomial regression on log(variance)~log(mean), with 2 degrees of freedom.

2.4 Differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

We used the EBSeq package (Leng et al., 2013) to assess the probability of a gene being differentially expressed between two stages or two clusters. Given any two conditions, the false discovery rate (FDR) is calculated based on the replicate or triplicate samples. We also calculated the normalized ECs for each condition (using the EBSeq method). We required that DEGs should have FDR < 5% and > 2 fold-change of average normalized ECs between any given two conditions.

In the case of our comparative analysis of Xenopus development, we acquired published data from (Owens et al., 2016). We used their calculated gene expression values (Gaussian process lower median of ‘Transcripts per Embryo’/10000) for each stage. See (Owens et al., 2016) for details. We only used gene expression values from the same stages as our axolotl data. We then defined DEGs as genes that showed a greater than two-fold change of (‘expression value’ + 1).

To compare HOX genes between axolotl and Xenopus (Owens et al., 2016), we used a log10 transformed “expression measure +1” method (Chaudhuri et al., 2011; Shalek et al., 2014). The addition of a value of 1 to ‘expression measure’ avoids undefined arithmetic and suppresses reporting of high fold-ratio expression changes for genes with relatively low expression in one or both sample groups.

2.5 Gene ontology analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the R/allez package (Newton et al., 2007) with each of 52 sets of DEGs (16 stage-to-stage analyses, 6 cluster-to-cluster analyses, 4 long time interval stage-to-stage comparisons, with one set each of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs for each analysis). Only GO terms with 50 to 800 associated genes were considered. GO terms with Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p values less than 0.01 were considered as enriched.

2.6 Hierarchical clustering analysis

We clustered the stages based on correlations of their gene expression vectors. To do so, we calculated the normalized ECs (Leng et al., 2013) for each sample. Then, for each stage we averaged the normalized ECs of each gene across all replicates from that stage. We then calculated, for each pair of stages, the Spearman correlation (Rho) of their normalized, averaged gene expression vectors. We performed hierarchical clustering on these pairwise Spearman correlations and assessed the stage clustering confidence by cluster bootstrapping analysis (5000 iterations) via the R package pvclust (Suzuki and Shimodaira, 2006). The correlation-based dissimilarity matrix (method.dist=”cor”) was used as the distance metric with average linkage. We calculated the approximately unbiased (AU) p-value and bootstrap probability (BP) value. The BP value is calculated by normal bootstrap resampling while the AU value is estimated by multiscale bootstrap resampling which results in a more robust approximation. The cluster dendrogram was re-plotted via the R package ‘dendextend’ and branches were rotated to position them according to their timing over development.

2.7 Axolotl expressed species-specific genes

We defined axolotl expressed “genes” as clustered contigs with aggregate TPM > 1 in any of the samples. Note that for the axolotl expressed species-specific gene analysis, we are only dealing with axolotl expression based on axolotl contigs mapping to either human or Xenopus annotation. This analysis is annotation-based, not expression-based. We are not considering Xenopus gene expression. For identifying axolotl expressed genes, we initially based our comparison on human reference gene sets. We then sought to find out how many axolotl genes based on the human reference had homologous genes in Xenopus. First, we annotated homolog information based on the Ensembl ortholog table (Human to Xenopus) (version 82). We then matched the human gene symbols to Xenopus gene symbols (NCBI RefSeq Xenopus annotation dated 8/3/2015) as well as Xenbase (xenbase.org version 3.6.2). This gave different tiers of confidence about whether an expressed axolotl gene derived from human homology is based on the Ensembl ortholog table or gene symbol match or both. An axolotl gene derived only from human homology (AxHu) is defined as an expressed axolotl human-mapped gene without any Xenopus homolog (based on the Ensembl ortholog table) and no matched Xenopus gene symbol (based on the RefSeq Xenopus gene set and Xenbase). We determined the expressed axolotl genes derived from Xenopus homology in an analogous way. For axolotl expressed genes based on Xenopus reference gene sets, we annotated homolog information based on the Ensembl ortholog table (Xenopus to Human) (version 82). We then matched the Xenopus gene symbols to Human gene symbols using both RefSeq (NCBI RefSeq Human annotation dated 12/7/2009) and HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) (genenames.org accessed 10/14/2015). An axolotl gene derived only from Xenopus homology (AxXen) is defined as an expressed axolotl Xenopus-mapped gene without any Human homolog (based on Ensembl ortholog table) and no matched Human gene symbol (based on RefSeq Human gene set and HGNC).

We further mapped AxHu genes to all Xenopus transcripts (Ensembl) as well as Xenopus genomic DNA via FASTA (Pearson and Lipman, 1988). Again, for these AxHu genes, we calculated our confidence that they do not have Xenopus homologs, based on the E-values of their most significant hits. A high confidence AxHu gene is defined as a gene with neither E-value of mapping to Xenopus transcripts nor Evalue of Xenopus genomic DNA less than 10−5. AxHu genes are defined as low confidence human specific genes if they have a FASTA match (E-value less than 10−5) to Xenopus. We defined the confidence of AxXen genes using the same method, but mapping AxXen genes against human transcripts and human genomic DNA. These high and low confidence labels are relatively ad-hoc measures of species-specificity.

3. Results

3.1 Sequencing, contig assembly, comparative mapping, and gene expression quantification

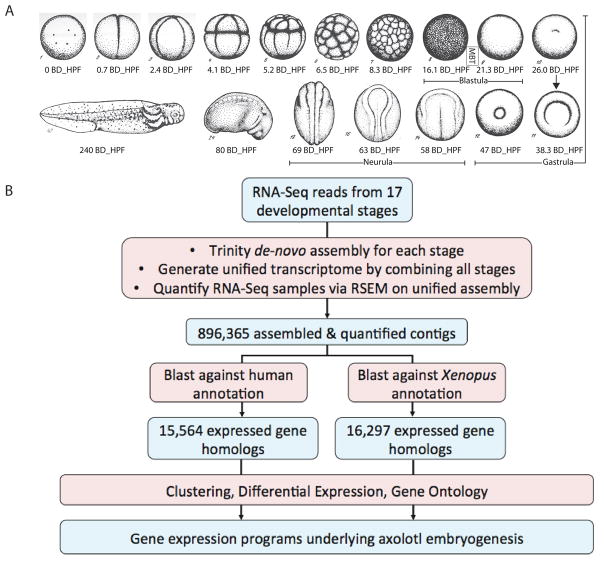

To investigate the transcriptional profile of embryogenesis in the axolotl, we gathered samples from 17 distinct developmental stages from egg through tadpole (Fig. 1A). For each stage, we collected biological replicates (stage 1 and stage 11) or triplicates (stages 2–10, stage 12, stage 14, stage 16, stage 19, stage 24, and stage 40). We then isolated messenger RNA (mRNA) from these samples using polyA+ selection and performed sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq platform with 2 × 101bp paired end RNA-Seq reads (~ 31M paired reads per sample) (Table S1). After trimming away adapter sequences, we built de novo transcriptomes for each of the 17 developmental stages by employing the Trinity software package (Grabherr et al., 2011) on pooled reads from replicates of the same stage. We then constructed a union of the contigs from all developmental stages and mapped the adapter trimmed RNA-seq reads to this unified contig set. To assign gene annotations for these contigs, we matched the contigs to the RefSeq human annotation via BLAST, using the best hit with an E-value < 10−5 to garner gene annotation (Altschul et al., 1990) (Fig. 1B). Using this approach, we assigned these contigs to 15,564 annotated human genes (Fig. 1B). Note that the labeling of these contigs with human gene names is not an indicator of orthology. Typically, reciprocal alignments must be performed to assign orthology (Li et al., 2003); however, this requires the availability of a genome assembly for both species to allow proper grouping of isoforms. No complete genome assembly for the axolotl exists. Without such an assembly, gene identification was performed with one way alignments (Coppe et al., 2010; Qiao et al., 2013). Because of this caveat, our gene identification is only identifying the closest human homolog of the axolotl contig and thus should be considered tentative. The median-by-ratio normalized expected counts (normalized ECs) and transcripts per million (TPM) for each gene in each sample were estimated via RNA-seq by Expectation-Maximization (RSEM) (Li and Dewey, 2011; Li et al., 2010). The detailed sample information, including read depth, mapping rate, and the number of contigs for each stage, can be found in Table S1 and Table S2.

Figure 1. RNA-Seq analysis of embryonic development in the unsequenced axolotl.

A. Drawings of axolotl developmental stage samples collected for RNA sequencing. Representative samples from critical developmental time points, such as the zygote, blastula, gastrula, and neurula are present. Images and timing (hours post fertilization (BD_HPF)) adapted from the Axolotl Newsletter, Spring 1979 (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979). B. Flow chart of sequencing data analysis. RNA-Seq reads were assembled with the Trinity package and BLASTed against either the human or Xenopus gene annotation set. Samples were clustered and stage-to-stage gene expression differences were calculated. For the human-annotated set gene ontology enrichment analysis was also performed.

We observe 15,564 genes detected (“detected” defined here as having a TPM > 1) in at least one of the stages sampled, with individual samples averaging 11,373 genes detected (Table S3). Although the number of genes detected rises at later stages, we nonetheless detected more than 10,000 genes in each pre-MBT stage (Table S3), indicating substantial complexity of the pre-MBT transcriptome of the axolotl, as has been observed in other species (Paranjpe et al., 2013; Tadros and Lipshitz, 2009; Tan et al., 2013; Yanai et al., 2011). A comparison of replicates showed that the gene expression values between samples within each stage are highly correlated (Fig. 2A and Table S4). We are interested in changes in transcriptome dynamics, and high variance at any particular stage can affect the ability to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Thus, gene specific within-condition mean and variance were estimated within each of the 17 stages (Fig. 2B). For each stage, the global mean-variance relationship is represented by a fitted curve using all estimates in this stage. The fitted curves are similar for all 17 stages, indicating that no particular stage has unusually high or low variance at any particular mean level.

Figure 2. The reproducibility of replicates.

A. Pairwise Spearman’s rank correlations between samples. The color key indicates the Spearman correlation coefficient (Rho). The histogram indicates the distribution of correlation over the sample to sample comparisons. Biological replicates and developmental stages cluster together. B. Within-condition mean and variance estimates for all genes and all 17 stages. Each circle represents paired mean-variance estimates of one gene within one stage. The stage-specific fitted mean-variance curves are shown as colored lines. The 17 stages are shown in different colors. The trend lines are similar for all stages indicating that no stage has unusually high variance at any particular mean measure. See text for additional details.

3.2 Transcriptome dynamics of embryogenesis

To systematically examine the transcriptomic dynamics of axolotl development, we performed pairwise stage-to-stage comparisons to identify DEGs (Materials and Methods). The number of upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) DEGs between any two stages is shown in figure 3A and table S5. When plotted over time, this DEG data reveals six developmental phases: three major waves of significant transcriptome changes (Fig. 3B), each followed by a time period of relative transcriptome stability. As the timing between stages varies over embryonic development, and because we did not sample every developmental stage, we plotted our data as the rate of DEGs (DEG/time) vs. hours post fertilization. Because of the difficulty in determining precise fertilization timing in our co-housed animals breeding overnight, we derived timing information from (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979) and refer to this measurement as BD_HPF. The term BD_Hour is also employed in order to refer to the time elapsed between developmental stages and is meant as a relative measure to allow for computing a rate of DEG (DEG/BD_Hour).

Figure 3. Transcriptome dynamics of embryogenesis.

A.Heat map of pairwise differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among developmental stages. The histogram indicates the distribution of the number of DEGs between pairwise stage comparisons. DEGs have false discovery rates < 5% and > 2 fold-change of average median-by-ratio normalized expected counts (normalized ECs) between any two stages. Upregulated genes are reflected in the top right corner in red. Downregulated genes are in the bottom left corner in blue. Each box indicates the number of DEGs between any two stages. B. Rate of differential gene expression between stages over time. Red dots represent the number of genes upregulated over time relative to the previous stage. Blue dots represent number of genes downregulated over time relative to the previous developmental stage. The figure is scaled by time (hours post fertilization using the timing information adapted from (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979) BD_HPF). Note that since the data represents the number of differentially expressed genes between stages, the data points are located at the mid-point (with regard to BD_HPF) between the two stages being compared.

For the majority of our samples, we are only examining the polyA+ fraction of the transcriptome. We realize that, especially prior to the MBT, many changes in the polyA+ level are likely caused by polyadenylation, deadenylation, or degradation (Audic et al., 1997; Graindorge et al., 2006). We use the terms upregulated and downregulated to indicate a change in the polyA+ transcript level without specifying whether the observed change is caused by changes in adenylation state, RNA degradation, or de novo transcription. Nevertheless, the polyA+ fraction of transcripts represents the portion of transcribed mRNA that is stabilized and poised to become translated and processed into protein (Colgan and Manley, 1997). Thus, we are examining the share of the transcriptome most likely to result in functional products of the genome.

The first phase, marking a wave of transcriptomic dynamism, is from the one-cell stage (stage 1) to the two-cell stage (stage 2), where there is a high rate of accumulation of DEGs per unit time (1451 DEGs/BD_Hour) (Fig. 3). Gene ontology (GO) analysis (see Materials and Methods) shows that protein phosphatase binding is significantly associated with the 676 upregulated genes (Table S6) from stage 1 to stage 2 (P = 9.69E-3, all GO P values are Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted) (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) (see Table S7 for enriched GO terms for upregulated genes). Several muscle related terms, such as sarcomere (P = 7.18E-15), muscle system process (P = 2.97E-9), and muscle contraction (P = 3.25E-9), are significantly enriched in the 257 downregulated genes (Table S8) from stage 1 to stage 2 (see Table S9 for enriched GO terms for downregulated genes), which could reflect the strong myosin dependent contractile wave activity present at the one-cell stage in amphibians (Christensen et al., 1984).

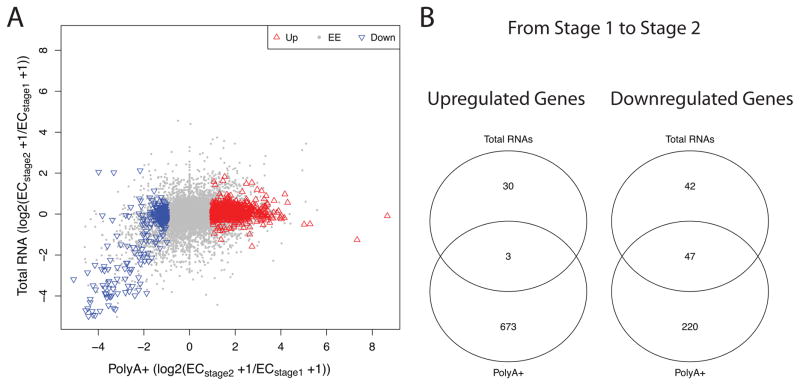

To distinguish between polyadenylation of maternal mRNAs and de novo transcription, we performed total RNA isolations of the stage 1 and stage 2 samples (see Materials and Methods) followed by RNA-sequencing to garner total RNA expression measures (Table S10). Comparison with the polyA+ analysis strongly supports the hypothesis that almost all of the observed upregulation in polyA+ transcripts from stage 1 to stage 2 is due to polyadenylation of existing maternal transcripts, rather than de novo transcription. When we plot the differentially expressed genes between stage 1 and stage 2 for the polyA+ selection vs. total RNA protocol (Fig. 4A) we observe a significant correlation among downregulated genes (Spearman’s rank correlation test, Rho = 0.57, p-value < 2.2e−16). However, the upregulated DEGs are very poorly correlated (Spearman’s rank correlation test, Rho = 0.003, p-value = 0.93), indicative of polyadenylation (rather than de novo transcription) underlying this change between stage 1 and stage 2.

Figure 4. PolyA+ vs. total RNA in stage 1 to stage 2.

A. Scatter plot of genes upregulated and downregulated between stages 1 and 2 for polyA+ vs. total RNA protocols. For the polyA+ protocol (x-axis), the median-by-ratio normalized expected counts (EC) were calculated for stage 1 and stage 2, respectively. Then, fold changes between stage 1 and stage 2 (log2(ECstage2 +1/ECstage1 +1)) were obtained. Identical calculations for the for the total RNA protocol (y-axis) were performed. The red triangles indicate significantly upregulated genes and the blue triangles indicate significantly downregulated genes from stage 1 to stage 2, per the polyA+ analysis. B. Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes between polyA+ and total RNA protocols from stage 1 to stage 2.

Our data indicate that the vast majority of upregulated genes based on polyA+ data are not upregulated in the total RNA data (673 out of 676, 99.6%). Example genes are shown in figure S1A and S1B, wherein the total RNA level does not change between stages 1 and 2, while the polyA+ RNA level increases dramatically. These data are consistent with an interpretation that the vast majority of upregulation seen between stages 1 and 2 is owing to polyadenylation, not de novo transcription. Similarly, the majority of downregulated genes (220 out of 267, 82.4%) from stage 1 to stage 2 based on polyA+ data show no significant change based on total RNA data, consistent with deadenylation (Fig. 4B, Fig. S1C–D). Interestingly, only 47 genes are downregulated from stage 1 to stage 2 based on both the polyA+ data and total RNA data (Fig. 4B, Fig. S1E–F), a profile consistent with degradation. The fact that the majority of downregulated genes (based on polyA+ data) show no significant change in total RNA is consistent with profiles in Xenopus wherein the level of many maternally inherited RNA molecules are relatively stable until after the onset of zygotic transcription, when they are subsequently cleared (Walser and Lipshitz, 2011).

The second phase is between stage 2 and stage 8, where the polyA+ transcriptome exhibits minimal change, averaging only 15 DEGs/BD_Hour. This is consistent with the previously described period of transcriptional quiescence prior to the MBT in Xenopus (Almouzni and Wolffe, 1995; Newport and Kirschner, 1982b; Ruzov et al., 2004; Vassetzky et al., 2000).

This relative stability is followed by the third phase, a second wave of transcriptomic changes, from stage 8 to stage 9 (237 DEGs/BD_Hour). In other amphibians, stage 8 corresponds to the MBT, characterized by clearance of maternal transcripts and widespread activation of zygotic gene transcription (Newport and Kirschner, 1982a; Walser and Lipshitz, 2011). Based on the gross morphological similarity between Xenopus and axolotl embryonic development (Bordzilovskaya and Dettlaff, 1979) and the large increase in differentially expressed genes between stages 8 and 9, we believe the axolotl MBT occurs around this time, in agreement with prior studies (Lefresne et al., 1998; Signoret and Lefresne, 1971). For the 379 upregulated genes from stage 8 to stage 9, there are many enriched GO terms associated with embryonic development and patterning, such as regionalization (P = 2.68E-33), gastrulation (P = 5.08E-32), pattern specification process (P = 3.31E-29), embryonic morphogenesis (P = 9.49E-27), circulatory system development (P = 6.10E-23), tissue morphogenesis (P = 1.31E-16), and blood vessel development (P = 7.30E-18) (Table S7). In addition, we observe a set of 773 genes that are present at stage 1 and are downregulated from stage 8 to stage 9, consistent with patterns of maternal clearance observed in Xenopus (Graindorge et al., 2006).

The fourth phase is from stage 9 to stage 11, where, surprisingly, the transcriptome is at least as stable (11 DEGs/BD_Hour) as it was pre-MBT (15 DEGs/BD_Hour).

This is followed by the fifth phase, a third wave of dramatic change in the transcriptome from stage 11 to stage 14 (244 DEGs/BD_Hour, roughly 2/3 being upregulated genes). The upregulated genes during stages 11–14, in general, are most significantly associated with GO terms involved with protein synthesis, for example (translational elongation (P = 2.07E-137), translational termination (P = 1.28E-164), protein targeting to ER (P = 6.17E-131)) followed by RNA processing (mRNA metabolic process (P = 1.81E-103), RNA splicing (P = 1.59E-40), anterior/posterior patterning specification (P = 2.48E-28), pattern specification process (P = 3.04E-27)), and morphogenesis (organ morphogenesis (P = 8.13E-24), embryonic morphogenesis (P = 1.92E-17)).

Finally, stages 14–40 constitute the sixth phase, a period again marked by relative transcriptomic stability (42 DEGs/BD_Hour). Our relatively sparse sampling density, the longer time intervals, and the underlying increasing tissue complexity makes the interpretation of these DEG patterns somewhat more challenging than prior phases of development. However, during the mid to late neurula (stages 14–19) the transcriptome is almost as stable (24 DEGS/BD_Hour) as it was pre-MBT (15 DEGs/BD_Hour). Furthermore, between stages 14 and 19, organogenesis has not begun in earnest, so tissue complexity is still fairly low. Thus we consider stages 14–19 to represent a putative third time period of relative transcriptomic stability. Notably, this period is marked by the major morphogenic movements of the mid to late neurula stages.

The general organization of these developmental phases can also be distinguished by plotting a heatmap of the highly expressed and variant genes (TPM > 50, at least 10-fold change) over development (Figure S2).

We next performed additional analysis comparing the differential gene expression profiles between Xenopus and axolotl embryonic development. To do so, we acquired a Xenopus developmental gene expression dataset (Owens et al., 2016) and plotted the stage to stage DEGs in a similar manner as described in the Materials and Methods. We see a large wave of upregulated DEGs between stage 1 and stage 2, similar to the profile seen in our axolotl data (Fig. S3, Fig. 3B). In addition, while the times do not correspond exactly to the waves we observe in axolotl development, there is a distinct phase of Xenopus DEG upregulation beginning around the MBT. In addition, there is a large wave of downregulated DEGs that may represent a clearance of maternally inherited transcripts between stage 9 and stage 12 (Fig. S3). The divergences between these figures might be due to true biological variation in the general transcriptomic profiles between these two species. However, it could also be due to differences in experimental or data analysis methodologies.

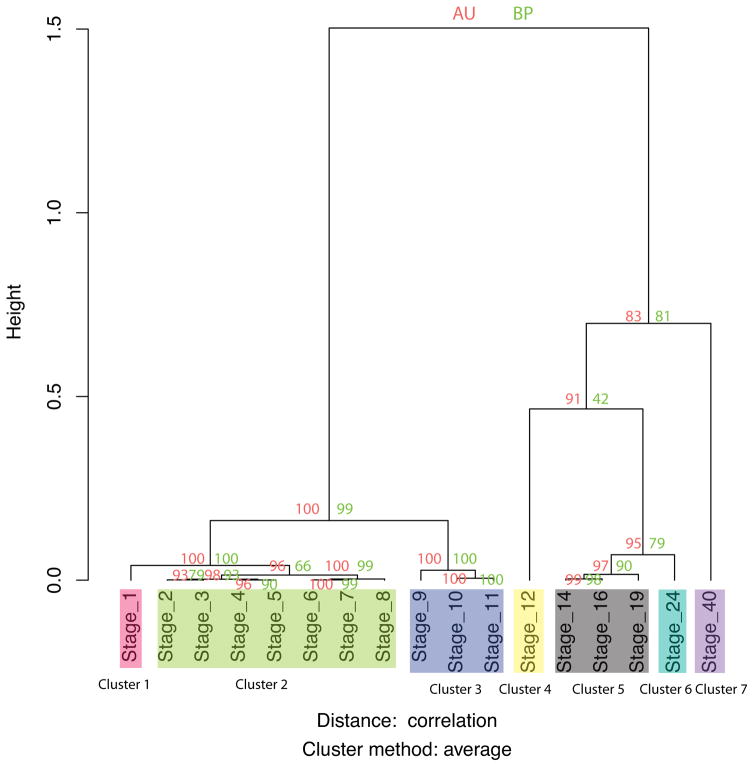

We also performed hierarchical clustering based on gene expression profiles among these stages. As shown in figure 5, the axolotl developmental stages group into 7 distinct clusters, including two clusters of pre-midblastula transition (pre-MBT) (cluster 1: stage 1, cluster 2: stages 2–8) and five clusters post-MBT (cluster 3: stages 9–11, cluster 4: stage 12, cluster 5: stages 14–19, cluster 6: stage 24, and cluster 7: stage 40). The developmental transitions between clusters correspond well to the waves and troughs of transcriptomic changes described above. Notably, stage 8 and stage 9 are clearly separated, further supporting the notion that the MBT begins at stage 8 in the axolotl, similar to other species (Newport and Kirschner, 1982a).

Figure 5. Hierarchical clustering based on gene expression profiles.

Stages were clustered using the PVclust R package based on correlations of their gene expression vectors. Notably, the clusters correspond very well with the phases of development identified by stage-to-stage differential gene expression analysis. For clustering, we calculated the median-by-ratio normalized expected counts (normalized ECs) (Leng et al., 2013) for each sample. Then, for each stage we averaged the normalized ECs of each gene across all replicates from that stage. We calculated, for each pair of stages, the Spearman correlation (Rho) of their normalized, averaged gene expression vectors. Hierarchical clustering was performed based on these pairwise correlation coefficients. Proximal stage branches of the dendrogram were grouped into 7 distinct developmental clusters. The height indicates the relative distance within and across clusters. We also calculated the approximately unbiased (AU) p-value and bootstrap probability (BP) values. The BP value is calculated by normal bootstrap resampling while the AU value is estimated by multiscale bootstrap resampling which results in a more robust approximation. These values indicate the relative confidence of the clustering. Additional information about the statistical techniques employed in the clustering can be found in the Materials and Methods section.

To investigate the functional significance of these clusters, we identified differentially expressed genes between each pair of clusters (as opposed to the previously described comparisons between developmental stages). The number of DEGs in pairwise cluster-by-cluster comparisons is shown in figure S4. As expected, there are many genes upregulated and downregulated between the clusters (Table S11 and Table S12), which can complicate the interpretation of GO analysis owing to the large number of significantly enriched terms. However, an example of a comparison that gives interpretable GO terms is between cluster 2 (stages 2–8) and cluster 3 (stages 9–11) which together straddle the MBT. GO analysis shows that there is a broad range of enriched GO terms associated with this transition (Table S13 and Table S14). The top three enriched GO terms in upregulated genes from cluster 2 (stages 2–8) to cluster 3 (stages 9–11) are segmentation (P = 4.82E-30), regionalization (P = 2.40E-25) and anterior/posterior pattern specification (P = 3.76 E-25) highlighting stages before and during gastrulation as critical for patterning and morphogenesis (Durston, 2015). For downregulated genes between these clusters, most of the highly-enriched GO terms are associated with DNA binding or transcription factor activity such as regulatory region DNA binding (P = 1.33E-9) and transcription regulatory region DNA binding (P = 4.12E-9), which may be representative of the widespread changes to gene regulatory programs occurring during this time period. In addition, when comparing the results from cluster 3 (stages 9–11) to cluster 4 (stages 12) we observe the enrichment of genes upregulated in GO terms associated with protein synthesis, development, and morphogenesis, highlighting the importance of these processes at the early stages of neurulation.

We also examined the DEG relationships between non-adjacent stages to identify longer scale trends in gene expression. For example, between stages 1 and 8, we find 17 upregulated GO terms related to extracellular matrix, calcium transport, protein targeting, and muscle related terms (adjusted p value < 0.001). In addition, we find 163 terms enriched based on down-regulated genes between stages 1 and 8, including terms related to protein targeting, ribosome/translation, and mRNA catabolism (adjusted p value < 0.001) (Table S15).

3.3 Comparison of axolotl data matched to Xenopus annotation

Although the human transcriptome is the best curated and annotated set available, the axolotl is estimated to be slightly more closely related phylogenetically to Xenopus tropicalis. The time since the most recent common ancestor for axolotl and human is ~350 million years while this time for axolotl and Xenopus is ~300 million years (Hedges et al., 2015). To examine whether the patterns observed using the human gene set annotation are robust, we mapped our assembled axolotl developmental contigs to NCBI’s RefSeq Xenopus annotation and repeated our analyses (Fig. 1B). The axolotl contigs mapped to a total of 16,297 Xenopus genes (versus 15,564 human genes), expressed (TPM > 1 calculated by RSEM) in at least one sample. For individual samples, an average of 11,513 genes were expressed (TPM > 1) (Table S16), similar to the value of 11,373 found in the human-based analysis.

We next calculated the differentially expressed genes between each pair of stages based on the Xenopus annotation. The pattern of the results corresponds closely with those observed using the human annotation. We observe the same waves of transcriptome changes (Fig. S5; compare with Fig. 3), and a grouping of stages into the same 7 clusters (Fig. S6; compare with Fig. 5). Thus, the choice of human or Xenopus as the gene annotation set for our axolotl expression contigs does not qualitatively alter the results. Taken together, the results are consistent between axolotl gene annotations based on the human gene set or on the Xenopus gene set.

In addition, we find 1,233 expressed axolotl genes derived only from human homology (AxHu genes), (Table S17), based on finding no Xenopus homolog in the Ensembl ortholog table and no gene symbol match between species (Materials and Methods). These AxHu genes may represent genes that are lost in the frog lineage but remain in the axolotl, or they may simply be the result of a more complete human annotation. We further evaluate the AxHu genes by comparing their sequences to the Xenopus genome and transcriptome via FASTA (see Materials and Methods), and find that the majority of the AxHu genes have some level of similarity to the Xenopus genome and/or transcriptome. We identify 118 AxHu genes without a good match to Xenopus sequence. We find 115 expressed axolotl genes derived only from Xenopus homology (AxXen genes), (Table S17), based on finding no human homolog in the Ensembl ortholog table and no gene symbol match between species (Materials and Methods). We further analyze the AxXen genes by comparing via FASTA to the human genome and transcriptome and find 21 AxXen genes without a good match to human sequence. Note that the AxHu and AxXen designations are derived from mapping axolotl contigs to human or Xenopus annotations. Quantitative expression values in axolotl or Xenopus play no role in determining these designations.

3.4 The developmental dynamics of the HOX gene family are conserved between axolotl and Xenopus

The HOX gene family is a group of transcription factors controlling the development of the body plan of the embryo along the anterior-posterior and proximo-distal axis (Durston, 2015; Zakany and Duboule, 2007). Our axolotl contigs map to 38 HOX genes based on human annotation (NCBI RefSeq, Materials and Methods). We also obtained expression values (“Gaussian process lower median of ‘Transcripts per Embryo’/10000”) for 38 Xenopus HOX genes from (Owens et al., 2016). Figure 6 shows the relative gene expression levels of these HOX genes over development (Note that H. sapiens has an annotated HOXB13 gene that is lacking in Xenopus, and Xenopus has an annotated hoxc3 gene that is lacking in H. sapiens.). In addition, we plotted each individual HOX gene’s relative expression vs. time for both axolotl (Fig. S7) and Xenopus (Fig. S8). The transcriptional profiles of these HOX genes are highly conserved between axolotl and Xenopus. Generally, the HOX genes display expression increases starting at stage 12 to stage 14. Interestingly, HOXD1 in both axolotl and Xenopus is expressed somewhat earlier (stage 8 in axolotl) and at a higher level than the other HOX genes. Hoxd1 in Xenopus has been previously shown to begin expression in the marginal zone during gastrulation, following activation by Brachyury and BMP-4 (Wacker et al., 2004).

Figure 6. HOX gene expression conservation between axolotl and Xenopus.

A. HOX gene expression over embryonic development in axolotl. The color key indicates the log10 transformed normalized transcripts per million (TPM) +1 measurement values. The histogram indicates the distribution of values over all stages and HOX genes. *HOXC3 is not present in our axolotl dataset based on the human transcriptome annotation. Additional information can be found in the Materials and Methods section. B. hox gene expression over embryonic development in Xenopus. Data from (Owens et al., 2016). The color key indicates the log10 transformed gene expression values (Gaussian process lower median of ‘Transcripts per Embryo’/10000, see (Owens et al., 2016) for details). The histogram indicates the distribution of values over all stages and hox genes. *hoxb13 is not present in Xenopus. Additional information can be found in the Materials and Methods section.

3.5 POU5F1 and SOX2 may play a role in zygotic gene activation

Previous studies have shown that Pou5f1, Nanog and members of the SoxB1 family are maternal transcription factors that activate zygotic gene expression during the MZT in zebrafish (Lee et al., 2013; Leichsenring et al., 2013). For these factors to be playing a role in zygotic gene activation in the axolotl, they would need to be present prior to the MBT. In the axolotl, we find evidence of moderate levels of POU5F1 transcripts in our data pre-MBT (Fig. S9A) (Note that some fraction of POU5F1 expression reported by RSEM is possibly due to the presence of axolotl POU5F3 transcripts that cannot be annotated via our methodology because there is no POU5F3 homolog in humans.) Zebrafish SOXB1 is represented by a group of genes in human, including SOX1, SOX2, and SOX3. In our axolotl data mapped to human genes, we only find contigs with significant BLAST matches to SOX2, which is expressed moderately pre-MBT (Fig. S9B). We find only very low levels of NANOG pre-MBT (Fig. S9C). These data indicate a potential role for Pou5f1 and Sox2 in axolotl zygotic gene activation. Further experimentation is needed to determine if these or other maternal genes present pre-MBT are necessary for zygotic gene activation in the axolotl.

4. Discussion

Early development requires cell-cell interactions, morphogenesis, and differentiation to be well controlled over both time and space. Investigating gene expression is a first step toward understanding regulation of these processes. Here we find that the axolotl developmental transcriptome can be broken down into six phases: three distinct waves of change each followed by three periods of relative transcriptome stability. The general pattern of transcriptomic change interspersed with relative transcriptome stability has been previously observed in other organisms ranging from Caenorhabditis elegans (Baugh et al., 2003) to mouse (Mitiku and Baker, 2007). However, global transcriptomic stability during early gastrulation and mid to late neurulation has not been described in amphibians to the best of our knowledge. The first period of stability corresponds to the time period of transcriptional quiescence prior to the MBT in amphibians (Newport and Kirschner, 1982b; Ruzov et al., 2004). The second and third periods of stability in the axolotl correspond to the times of the major morphogenic movements of gastrulation and neurulation. It should be noted that during these stable periods, early to mid gastrula (phase 4) and the mid to late neurula (beginning of phase 6), the transcriptome is approximately as stable (measured in DEGs/unit time) as it is in the stable pre-MBT stages between stages 2 and 8 (two cell to mid-blastula).

We have identified a number of interesting features in our transcriptome dataset, the discussion of which we have organized according to their developmental phase, defined by changes in DEGs across stage transitions. Note that, since phases are defined by changes between stages, two adjacent phases will share a stage.

4.1 Phase 1 (Stages 1–2) – Post-fertilization

We see both downregulation and upregulation of transcripts from stage 1 to stage 2, with upregulation dominating (Fig 6B). The conventional interpretation, supported by our total RNA vs. polyA+ RNA analysis (Fig 6A), is that much of the downregulation is due to degradation and deadenylation of maternal transcripts. The downregulated genes are enriched in muscle related GO terms, potentially owing to the importance of myosin contractile proteins in the response to sperm entry into the ovum (Christensen et al., 1984). The total RNA vs. polyA+ RNA comparisons agree with results in Xenopus (Audic et al., 1997; Collart et al., 2014; Graindorge et al., 2006). Per Fig 6B, almost all upregulation (673 out of 676 genes, 99.6%) during this phase is likely the result of polyadenylation rather than de novo transcription, concurring with studies in Xenopus (Collart et al., 2014; Paranjpe et al., 2013).

4.2 Phase 2 (Stages 2–8) – Cell division and transcriptomic stability pre-MBT

During phase 2, the embryo enters a state marked by repeated coordinated cell division, with relatively few changes in the overall polyA+ transcript composition. Given the relative paucity of de novo zygotic transcription pre-MBT in Xenopus (Tadros and Lipshitz, 2009), this finding is expected.

4.3 Phase 3 (Stages 8–9) – Activating the zygotic genome and degrading maternal transcripts

Between stage 8 and stage 9, we see a marked alteration in the polyA+ transcriptome, with significant GO enrichment of segmentation, regionalization, anterior/posterior specification, somite development and gastrulation terms. This change is most likely due to the initiation of zygotic transcription as well as the large scale clearance of inherited maternal transcripts (Walser and Lipshitz, 2011). More specifically, these changes probably reflect the early cellular differentiation and patterning that occurs throughout this phase (Elinson and del Pino, 2012).

4.4 Phase 4 (Stages 9–11) – Gastrulation and transcriptomic stability

The transcriptome between stages 9 (late blastula) and 11 (mid gastrula) is very stable with a rate of DEG change lower than that seen pre-MBT (phase 2). We envision that the activation of zygotic transcription in the previous phase prepares the embryo for the complex patterning and morphogenic steps to follow. Perhaps during Phase 4, morphogenesis, migration, and cell-cell communication are prioritized over transcriptional change.

4.5 Phase 5 (Stages 11–14) – Late Gastrula and Early Neurulation

Another transcriptomic upheaval begins in the late gastrula and continues into early neurulation (stages 11–14). Among these genes we see significant enrichment of GO categories related to translation, protein trafficking, metabolism, neuronal development and axon guidance.

4.6 Phase 6 (Stages 14–40) – Late stage transcriptomic stability

We see a final relatively stable phase between stage 14 and stage 40, corresponding to late neurula through tadpole. The early portion of this phase, between stages 14 and 19, is particularly stable with only 24 DEGs/BD_Hour, a rate almost as low as pre-MBT (phase 2). These stages (14–19) correspond to the closing of the neural tube and are known to feature abundant cell migration and morphogenesis (Colas and Schoenwolf, 2001). We consider stages 14–19 to represent a putative third stage of transcriptomic stability. From stage 19 to stage 40, the overall rate of transcriptome change remains fairly low (43 DEGs/BD_Hour). However, it is possible that during later stages it is more difficult to detect transcriptional changes owing to the increasing tissue complexity of the whole embryo.

4.7 Annotation of axolotl gene expression

We observe similar gene numbers and sample clustering results whether axolotl expressed contigs are mapped to the human or Xenopus annotation, indicating that the gene set used does not dramatically alter the results of our analysis of the unsequenced axolotl transcriptome. However, mapping the axolotl to these two different species’ gene sets does allow the identification of putative species-specific genes. We identify 21 putative amphibian-specific genes and 118 putative human-annotated genes expressed in the axolotl without an obvious Xenopus match (Table S17).

We observe a conservation of HOX gene expression profiles between axolotl and Xenopus, including an early and abundant expression of HOXD1. HOXD1 may play a role in anterior-posterior patterning during gastrulation (Durston et al., 2010).

5. Conclusions

Ultimately, this work represents a rich resource for the developmental biology and axolotl communities. It will undoubtedly aid in the study of the evolution and conservation of gene expression programs underlying development. Our observations regarding waves of transcriptomically dynamic periods followed by stable states could be widely present throughout the development of other vertebrates and bears additional examination. Finally, we remain interested in the extent to which the axolotl, in displaying its remarkable regenerative capabilities, re-accesses gene expression networks utilized during development. Studies like this will allow us to begin to address this particularly intriguing question.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Sequenced transcriptomes of 17 stages of embryonic development in the axolotl

Peaks of transcriptional dynamism punctuate relatively stable states

Stable states occur during major morphogenetic events: gastrulation, neurulation

Acknowledgments

J.D.N. was supported by an NHGRI training grant to the Genomic Sciences Training Program 5T32HG002760. C.N.D. was supported by NIH grants R01HG005232 and U54AI117924. We thank Marv and Babe Conney for a grant to R.S. and J.A.T. We also thank Mackenzie Holland for editorial assistance, as well as Jen Bolin and Bao Kim Nguyen for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aanes H, Winata CL, Lin CH, Chen JP, Srinivasan KG, Lee SG, Lim AY, Hajan HS, Collas P, Bourque G, Gong Z, Korzh V, Alestrom P, Mathavan S. Zebrafish mRNA sequencing deciphers novelties in transcriptome dynamics during maternal to zygotic transition. Genome Res. 2011;21:1328–1338. doi: 10.1101/gr.116012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almouzni G, Wolffe AP. Constraints on transcriptional activator function contribute to transcriptional quiescence during early Xenopus embryogenesis. The EMBO journal. 1995;14:1752. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic Y, Omilli F, Osborne HB. Postfertilization deadenylation of mRNAs in Xenopus laevis embryos is sufficient to cause their degradation at the blastula stage. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:209–218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessari D, Shin Y, Krebs O, Konig R, Koide T, Vinayagam A, Fenger U, Mochii M, Terasaka C, Kitayama A, Peiffer D, Ueno N, Eils R, Cho KW, Niehrs C. Global gene expression profiling and cluster analysis in Xenopus laevis. Mech Dev. 2005;122:441–475. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh LR, Hill AA, Slonim DK, Brown EL, Hunter CP. Composition and dynamics of the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryonic transcriptome. Development. 2003;130:889–900. doi: 10.1242/dev.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bordzilovskaya NP, Dettlaff TA. Table of stages of the normal development of axolotl embryos and the prognostication of timing of successive developmental stages at various temperatures. Axolotl Newsletter. 1979;7:2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri RR, Yu L, Kanji A, Perkins TT, Gardner PP, Choudhary J, Maskell DJ, Grant AJ. Quantitative RNA-seq analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni transcriptome. Microbiology. 2011;157:2922–2932. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.050278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Sauterer R, Merriam RW. Role of soluble myosin in cortical contractions of Xenopus eggs. Nature. 1984;310:150–151. doi: 10.1038/310150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colas JF, Schoenwolf GC. Towards a cellular and molecular understanding of neurulation. Developmental dynamics. 2001;221:117–145. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DF, Manley JL. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes & development. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart C, Owens ND, Bhaw-Rosun L, Cooper B, De Domenico E, Patrushev I, Sesay AK, Smith JN, Smith JC, Gilchrist MJ. High-resolution analysis of gene activity during the Xenopus mid-blastula transition. Development. 2014;141:1927–1939. doi: 10.1242/dev.102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppe A, Pujolar JM, Maes GE, Larsen PF, Hansen MM, Bernatchez L, Zane L, Bortoluzzi S. Sequencing, de novo annotation and analysis of the first Anguilla anguilla transcriptome: EeelBase opens new perspectives for the study of the critically endangered European eel. BMC genomics. 2010;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinsmore CE. A History of Regeneration Research. 1. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge (England): 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Durston AJ. Time, space and the vertebrate body axis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;42:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston AJ, Jansen HJ, Wacker SA. Review: Time-space translation regulates trunk axial patterning in the early vertebrate embryo. Genomics. 2010;95:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson RP, del Pino EM. Developmental diversity of amphibians. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology. 2012;1:345–369. doi: 10.1002/wdev.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graindorge A, Thuret R, Pollet N, Osborne HB, Audic Y. Identification of post-transcriptionally regulated Xenopus tropicalis maternal mRNAs by microarray. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:986–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M, Paymer M, Kumar S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:835–845. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinath MC, Timoshevskiy VA, Timoshevskaya NY, Tsonis PA, Voss SR, Smith JJ. Initial characterization of the large genome of the salamander Ambystoma mexicanum using shotgun and laser capture chromosome sequencing. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16413. doi: 10.1038/srep16413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattak S, Murawala P, Andreas H, Kappert V, Schuez M, Sandoval-Guzman T, Crawford K, Tanaka EM. Optimized axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) husbandry, breeding, metamorphosis, transgenesis and tamoxifen-mediated recombination. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:529–540. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MT, Bonneau AR, Takacs CM, Bazzini AA, DiVito KR, Fleming ES, Giraldez AJ. Nanog, Pou5f1 and SoxB1 activate zygotic gene expression during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature. 2013;503:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature12632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefresne J, Andeol Y, Signoret J. Evidence for introduction of a variable G1 phase at the midblastula transition during early development in axolotl. Dev Growth Differ. 1998;40:497–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1998.t01-3-00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring M, Maes J, Mossner R, Driever W, Onichtchouk D. Pou5f1 transcription factor controls zygotic gene activation in vertebrates. Science. 2013;341:1005–1009. doi: 10.1126/science.1242527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng N, Dawson JA, Thomson JA, Ruotti V, Rissman AI, Smits BM, Haag JD, Gould MN, Stewart RM, Kendziorski C. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Ruotti V, Stewart RM, Thomson JA, Dewey CN. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:493–500. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome research. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitiku N, Baker JC. Genomic analysis of gastrulation and organogenesis in the mouse. Dev Cell. 2007;13:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale DB, Wegrzyn JL, Stevens KA, Zimin AV, Puiu D, Crepeau MW, Cardeno C, Koriabine M, Holtz-Morris AE, Liechty JD, Martinez-Garcia PJ, Vasquez-Gross HA, Lin BY, Zieve JJ, Dougherty WM, Fuentes-Soriano S, Wu LS, Gilbert D, Marcais G, Roberts M, Holt C, Yandell M, Davis JM, Smith KE, Dean JF, Lorenz WW, Whetten RW, Sederoff R, Wheeler N, McGuire PE, Main D, Loopstra CA, Mockaitis K, deJong PJ, Yorke JA, Salzberg SL, Langley CH. Decoding the massive genome of loblolly pine using haploid DNA and novel assembly strategies. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R59. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell. 1982a;30:675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell. 1982b;30:687–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton MA, Quintana FA, Den Boon JA, Sengupta S, Ahlquist P. Random-set methods identify distinct aspects of the enrichment signal in gene-set analysis. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2007:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). A systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. 1956:22. [Google Scholar]

- Nye HL, Cameron JA, Chernoff EA, Stocum DL. Regeneration of the urodele limb: a review. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:280–294. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens ND, Blitz IL, Lane MA, Patrushev I, Overton JD, Gilchrist MJ, Cho KW, Khokha MK. Measuring Absolute RNA Copy Numbers at High Temporal Resolution Reveals Transcriptome Kinetics in Development. Cell reports. 2016;14:632–647. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe SS, Jacobi UG, van Heeringen SJ, Veenstra GJ. A genome-wide survey of maternal and embryonic transcripts during Xenopus tropicalis development. BMC genomics. 2013;14:762. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W, Lipman D. Improved tools for biological sequence analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Yang W, Fu J, Song Z. Transcriptome profile of the green odorous frog (Odorrana margaretae) PloS one. 2013;8:e75211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss C, Olsson L, Hossfeld U. The history of the oldest self-sustaining laboratory animal: 150 years of axolotl research. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2015;324:393–404. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzov A, Dunican DS, Prokhortchouk A, Pennings S, Stancheva I, Prokhortchouk E, Meehan RR. Kaiso is a genome-wide repressor of transcription that is essential for amphibian development. Development. 2004;131:6185–6194. doi: 10.1242/dev.01549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalek AK, Satija R, Shuga J, Trombetta JJ, Gennert D, Lu D, Chen P, Gertner RS, Gaublomme JT, Yosef N. Single cell RNA Seq reveals dynamic paracrine control of cellular variation. Nature. 2014;510:363. doi: 10.1038/nature13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signoret J, Lefresne J. Contribution à l’étude de la segmentation de l’œuf d’axolotl. I-Définition de la transition blastuléenne. Ann Embryol Morphogen. 1971;4:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Skirkanich J, Luxardi G, Yang J, Kodjabachian L, Klein PS. An essential role for transcription before the MBT in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2011;357:478–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JJ, Putta S, Zhu W, Pao GM, Verma IM, Hunter T, Bryant SV, Gardiner DM, Harkins TT, Voss SR. Genic regions of a large salamander genome contain long introns and novel genes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Rascon CA, Tian S, Nie J, Barry C, Chu LF, Ardalani H, Wagner RJ, Probasco MD, Bolin JM, Leng N, Sengupta S, Volkmer M, Habermann B, Tanaka EM, Thomson JA, Dewey CN. Comparative RNA-seq analysis in the unsequenced axolotl: the oncogene burst highlights early gene expression in the blastema. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1002936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1540–1542. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W, Lipshitz HD. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: a play in two acts. Development. 2009;136:3033–3042. doi: 10.1242/dev.033183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MH, Au KF, Yablonovitch AL, Wills AE, Chuang J, Baker JC, Wong WH, Li JB. RNA sequencing reveals a diverse and dynamic repertoire of the Xenopus tropicalis transcriptome over development. Genome Res. 2013;23:201–216. doi: 10.1101/gr.141424.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsonis PA. Regeneration in vertebrates. Developmental biology. 2000;221:273–284. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassetzky Y, Hair A, Méchali M. Rearrangement of chromatin domains during development in Xenopus. Genes & development. 2000;14:1541–1552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesterlund L, Jiao H, Unneberg P, Hovatta O, Kere J. The zebrafish transcriptome during early development. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker SA, McNulty CL, Durston AJ. The initiation of Hox gene expression in Xenopus laevis is controlled by Brachyury and BMP-4. Developmental Biology. 2004;266:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walser CB, Lipshitz HD. Transcript clearance during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2011;21:431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai I, Peshkin L, Jorgensen P, Kirschner Marc W. Mapping Gene Expression in Two Xenopus Species: Evolutionary Constraints and Developmental Flexibility. Developmental Cell. 2011;20:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakany J, Duboule D. The role of Hox genes during vertebrate limb development. Genetics and Development. 2007;17:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.