Abstract

Background

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are a consumer product whose benefits and risks are currently debated. Advocates of the “tobacco harm reduction” strategy emphasize their potential as an aid to smoking cessation, while advocates of the precautionary principle emphasize their risks instead. There have been only a few studies to date on the prevalence of e-cigarette use in Germany.

Methods

In May 2016, in collaboration with Forsa, an opinion research firm, we carried out a survey among 4002 randomly chosen persons aged 14 and older, asking them about their consumption of e-cigarettes with and without nicotine, reasons for using e-cigarettes, plans for future use, estimation of danger compared to that of tobacco products, smoking behavior, and sociodemographic features.

Results

1.4% of the respondents used e-cigarettes regularly, and a further 2.2% had used them regularly in the past. 11.8% had at least tried them, including 32.7% of smokers and 2.3% of persons who had never smoked. 24.5% of ex-smokers who had quit smoking after 2010 had used e-cigarettes at least once. 20.7% of the respondents considered electronic cigarettes less dangerous than conventional cigarettes, 46.3% equally dangerous, and 16.1% more dangerous. An extrapolation of these data to the general population suggests that about one million persons in Germany use e-cigarettes regularly and another 1.55 million have done so in the past.

Conclusion

The consumption of electronic cigarettes in Germany is not very widespread, but it is not negligible either. Nearly 1 in 8 Germans has tried e-cigarettes at least once. Regular consumers of e-cigarettes are almost exclusively smokers and ex-smokers.

Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics (IMBEI) University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Obere Zahlbacher Str. 69 55131 Mainz, Germany eichler@uni-mainz.de

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are devices that convert liquids into inhalable vapor via a heating coil. They are available in various forms, all of which have a liquid reservoir, an energy source, a mouthpiece, and an electronic circuit to vaporize the liquid (1, 2). E-cigarettes are used for recreational purposes or as a tobacco and nicotine cessation aid. The liquids vaporized usually contain nicotine and can also contain a variety of aromas. In contrast to other possible ways of nicotine intake, such as patches or chewing gum, e-cigarettes mimic the smoking ritual.

Although already patented in the 1960s (3), e-cigarettes were not available as a product until their introduction on the Chinese market in 2004 (4). They have been widely available in Europe and Germany since 2010. Since then, the use of e-cigarettes has become a visible phenomenon in the Western world, with considerable differences in use between individual countries (etable 1). In several countries, new legislations are currently underway to regulate e-cigarette use (10, 11).

eTable 1. Use of electronic cigarettes in selected countries.

| N |

Age (years) |

Have tried e-cigarettes (%) |

Previous user e-cigarettes (%) |

Current user e-cigarettes (%) |

Ever user e-cigarettes (%) |

Never user e-cigarettes (%) |

|

| Germany 2015 (DKFZ) (2) |

1950 | >14 | – | – | – | 5.8 | – |

| Germany 2014 (Eurobarometer) (5) |

998 | >15 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 91 |

| Germany 2014 (Uni Heidelberg) (6) |

1015 | >16 | – | – | – | 8.2 | – |

| United Kingdom 2015 (ONS) (7) |

6150 | >16 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 17 | – |

| Europe 2014 (Eurobarometer) (5) |

27 801 | >15 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 87 |

| France 2014 (Health Barometer) (8) |

15 635 | 15–75 | – | – | 6 | 25.7 | – |

| USA 2014 (NHIS) (9) |

36 697 | >18 | – | – | 3.7 | 12.6 | – |

DKFZ, German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum); NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; ONS, Office for National Statistics

Over the past few years, a lively debate about the use of e-cigarettes has developed among physicians and health scientists. This debate involves three main questions:

What are the health risks of e-cigarette consumption, especially in the long term (12– 14)?

Are e-cigarettes an effective means of tobacco smoking and/or nicotine cessation (15– 17)?

Does e-cigarette use lead to the so-called renormalization of smoking and thus act as a gateway for tobacco consumption (18– 20)?

Along the lines of these questions, two juxtaposing public health positions are currently being discussed: the potential benefits of e-cigarettes are emphasized by supporters of the so-called tobacco harm reduction, while their potential risks are emphasized by advocates of the precautionary principle. The scientific discussion is made more difficult by the fact that these are normative positions, which hinders a dispassionate risk assessment. This has resulted in different countries assessing the potential benefits and risks associated with e-cigarette consumption differently. This is exemplified for instance by comparing the dominant positions taken in the UK and Germany (etable 2).

eTable 2. Addressing the issues of e-cigarettes in public health.

| Controversial issues | Germany | United Kingdom |

| Recommendation of use | Use is discouraged (21) | Under consideration recommending smokers who are unable or unwilling to stop smoking to switch (24) |

| Health risks | Aerosol contains fewer pollutants than tobacco smoke (2) | E-cigarettes are about 95% less harmful than cigarettes (24, 25) |

| Harmlessness to health not proven (21) | Likely to improve public health (26) | |

| Vapor not toxin-free (2) | Carcinogenic chemicals are largely absent (24) | |

| Aid for tobacco or nicotine cessation | No evidence for suitability as smoking cessation aid (22) | Emerging evidence for effectiveness as smoking cessation aid (24) |

| May reduce the motivation to quit smoking (22) | Reduces craving for smoking and can therefore help to quit smoking (25) | |

| Gateway to tobacco consumption | Could serve as gateway by imitating smoking (23) | No indications that use leads to increased smoking uptake (27) |

| Dual use | Risk of maintenance/increase of dependency (2) | No evidence for an increase in dependency (27) |

| Risk of passive exposure | Health can be impaired (2) | No identifiable risks for passive exposure (27) |

| Influence on public opinion | “Be aware of the dangers of e-cigarettes and e-shishas” (22) | “…growing misconception that e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes are similarly harmful.” (26) |

Germany and the UK have developed divergent positions in their assessment of e-cigarettes. Examples for this are given in statements intended for the general public in Germany published by the Division of Cancer Prevention of the Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (2), the German Federal Center for Health Education (21), and the Aktionsbündnis Nichtrauchen (Alliance for Non-Smoking) (22, 23), which can be compared to those from the UK issued by the equivalent parties (The National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training [25], Royal College of Physicians [26], and Action on Smoking and Health [27]

The frequency of e-cigarette consumption has now been well investigated in various countries (28– 30). However, only a few studies have addressed population-representative data on the prevalence and reasons for e-cigarette consumption in Germany (2, 5, 6). Moreover, these studies were either limited to a few key indicators, such as “used at least once” (6), or they could not determine any significant regular consumption (2). Our study examined the following parameters in a large sample:

Use of e-cigarettes in Germany

Frequency of use

Reasons for consumption

Use of nicotine

Possible future consumption

Perception of harm of e-cigarettes as compared to tobacco cigarettes, taking into account demographic factors.

Methods

Data collection and sampling

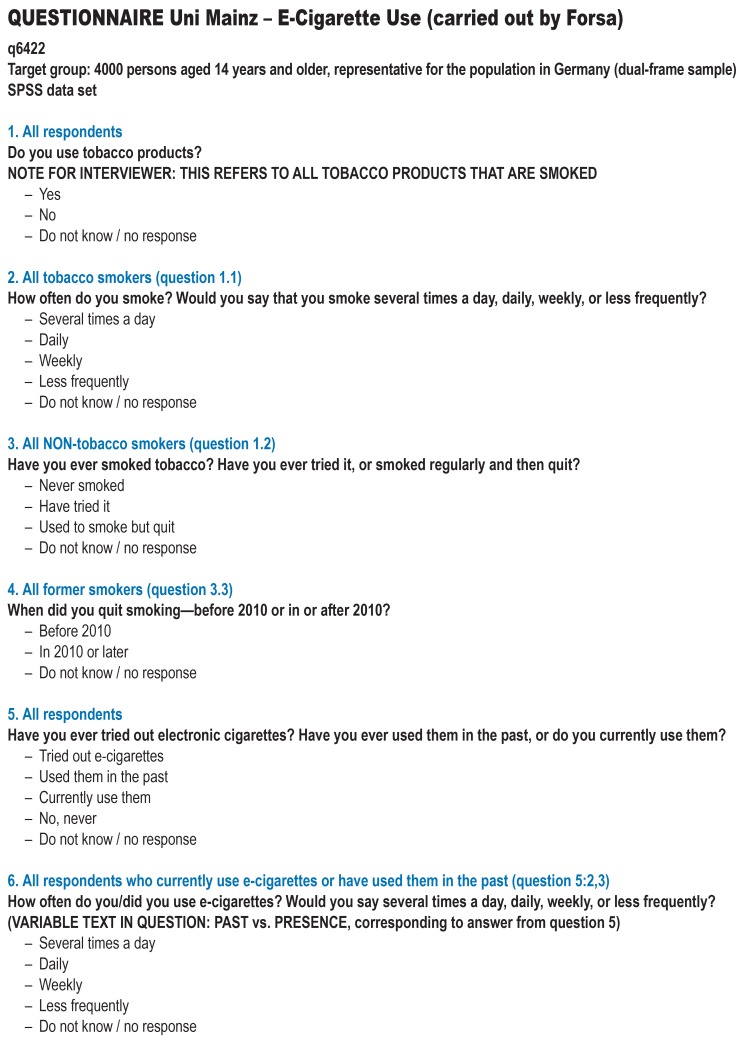

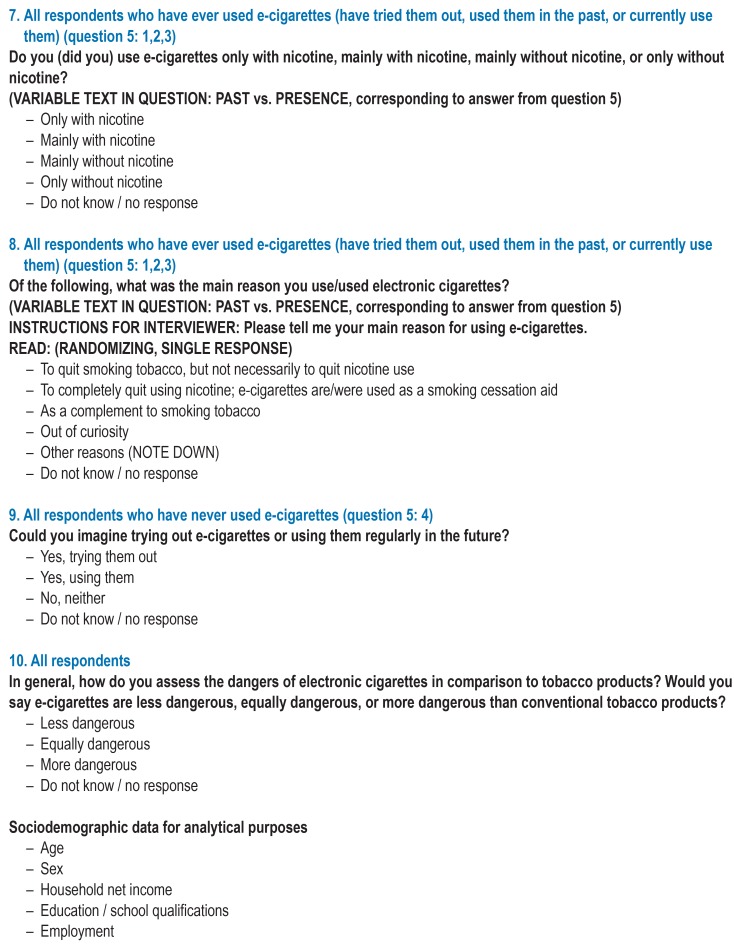

After the authors developed the questionnaire (efigure), data were collected by Forsa in May 2016. This market and opinion research firm is a member of the BVM (Bundesverband Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforscher, Association of German Market and Social Researchers) and the ADM (Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforschungsinstitute, Working Group of German Market and Social Research Firms).

eFigure.

Data were collected by computer-assisted telephone interviews according to the ADM telephone sampling system (31, 32). This is a multi-level systematic random sampling, in which calls are made to telephone numbers from all the possible telephone connections. If a telephone connection corresponded to the inclusion criteria (private residency, availability of selected person, knowledge of German), the potential participants were asked to participate in the survey. Both mobiles and landline network connections were contacted (33).

We aimed at interviewing 4000 individuals living in Germany, aged 14 years and over, by telephone. The following data were recorded:

Current and past consumption of tobacco products (smoker, ex-smoker who quit before 2010, ex-smoker who quit in 2010 or later, ever smoker, never smoker)

Current and past use of e-cigarettes (experimental use, former regular use, current regular use)

Use of liquids with or without nicotine

Reason for use of e-cigarettes

Possible future use of e-cigarettes (would try it out, would use it regularly)

Assessment of danger of e-cigarettes as compared to tobacco products

Socio-demographic data: age, sex, income, employment, household size, number of children in household, community size, and formal education (low = no qualification or Volks- or Hauptschulabschluss [year 9 lower secondary school certificate], medium = polytechnic secondary school [Polytechnische Oberschule; POS], Real- or Mittelschulabschluss [year 10 lower secondary school certificate]; high = Abitur, Fachabitur [secondary school certification, allows entrance to a university]) (eFigure, eTable 3).

eTable 3. Main demographic data of the study population (weighted with design weight, unweighted, weighted with design weight and education level), using comparative figures (if available).

|

Frequency (weighted with design weight) |

% |

Frequency (unweighted) |

% |

Frequency (weighted with design weight and education levels) |

% |

Selected representative figures for comparison % |

||

| Sex | Male | 1951 | 48.8 | 2058 | 51.4 | 1951 | 48.8 | 48.8*1 |

| Female | 2051 | 51.2 | 1944 | 48.6 | 2051 | 51.2 | 51.2*1 | |

| Household size (number of people) | 1 | 811 | 20.3 | 1004 | 25.1 | 865 | 21.6 | 20.3*2/*3 |

| 2 | 1495 | 37.4 | 1616 | 40.4 | 1476 | 36.9 | 34.2*2/*3 | |

| 3 | 672 | 16.8 | 569 | 14.2 | 646 | 16.1 | 18.6*2/*3 | |

| ≥ 4 | 970 | 24.2 | 743 | 18.6 | 962 | 24.0 | 27.0*2/*3 | |

| Household income | Mean*4 | 2500–3000 Euro | 74.9 | 3000–3500 Euro | 76.9 | 2500–3000 Euro | 75.9 | 3147 Euro*5 |

| No response | 1006 | 25.1 | 926 | 23.1 | 966 | 24.1 | – | |

| Education level*6 | Low | 690 | 17.2 | 670 | 16.7 | 1455 | 36.4 | 33.8*2 |

| Medium | 1148 | 28.7 | 1137 | 28.4 | 1148 | 28.7 | 29.6*2 | |

| High | 1771 | 44.3 | 1902 | 47.5 | 1118 | 27.9 | 28.8*2 | |

| Community size | Up to 5000 | 515 | 12.9 | 511 | 12.8 | 547 | 13.7 | 13.5*2 |

| 5000 to 10 000 | 408 | 10.2 | 405 | 10.1 | 449 | 11.2 | 10.8*2 | |

| 10 000 to 50 000 | 1360 | 34.0 | 1358 | 33.9 | 1351 | 33.8 | 32.0*2 | |

| 50 000 to 100 000 | 363 | 9.1 | 341 | 8.5 | 383 | 9.6 | 9.2*2 | |

| From 100 000 | 1269 | 31.7 | 1337 | 33.4 | 1188 | 29.7 | 34.5*2 | |

| Number of children under 18 years in household | 0 | 2745 | 68.6 | 2897 | 72.4 | 2786 | 69.6 | 79.9*2/*7 |

| 1 | 541 | 13.5 | 476 | 11.9 | 519 | 13.0 | 10.6*2/*7 | |

| 2 | 442 | 11 | 392 | 9.8 | 415 | 10.4 | 7.3*2/*7 | |

| 3 | 119 | 3.0 | 96 | 2.4 | 108 | 2.7 | 1.7*2/*7 | |

| 4*7 | 57 | 1.4 | 32 | 0.8 | 74 | 1.9 | 0.4*2/*7 | |

| Civil status | Married/life partner, together | 1936 | 48.4 | 1999 | 50.0 | 1911 | 47.8 | 56.6*1/*8 |

| Married but separated | 43 | 1.1 | 51 | 1,3 | 38 | 1.0 | k. A. | |

| Single | 1407 | 35.2 | 1171 | 29.3 | 1397 | 34.9 | 28.2*1/*8 | |

| Divorced | 289 | 7,2 | 380 | 9.5 | 313 | 7.8 | 8.5*1/*8 | |

| Widowed | 293 | 7,3 | 372 | 9.3 | 316 | 7.9 | 8.6*1/*8 | |

| Employed | Yes | 2045 | 51,1 | 2153 | 53.8 | 2010 | 50.2 | – |

| No | 1957 | 48,9 | 1849 | 46.2 | 1992 | 49.8 | – | |

| Selected professional positions | Civil servant | 157 | 3.9 | 170 | 4.2 | 114 | 2.8 | – |

| Laborer | 218 | 5.4 | 187 | 4.7 | 318 | 7.9 | – | |

| Self-employed | 246 | 6.1 | 332 | 8.3 | 216 | 5.4 | – | |

| Employee | 1334 | 33.3 | 1403 | 35.1 | 1239 | 31.0 | – | |

| Student | 270 | 6.7 | 154 | 3.8 | 184 | 4.6 | – | |

| University student | 182 | 4.5 | 102 | 2.5 | 154 | 3.8 | – | |

| Retired | 1033 | 25.8 | 1163 | 29.1 | 1082 | 27.0 | – | |

| Smoker status | Smoker | 980 | 24.5 | 942 | 23.5 | 1093 | 27.3 | 24.5*9 |

| Non-smoker | 3014 | 75.3 | 3035 | 75.8 | 2904 | 72.6 | 75.5*9 | |

| – Never smoker | 1360 | 34.0 | 1234 | 30.8 | 1267 | 31.7 | 56.2*9 | |

| – Have tried smoking | 627 | 15.7 | 655 | 16.4 | 606 | 15.2 | ||

| – Quit before 2010 | 798 | 19.9 | 932 | 23.3 | 803 | 20.1 | 19.3*9 | |

| – Quit in 2010 or later | 214 | 5.4 | 214 | 5.4 | 216 | 5.4 |

„“No response” values of less than 5% are not shown. Percentages refer to the total population of 4002.

*1 Census 2011; *2 Microcensus (MC) 2014; *3 numbers calculated by us based on the MC;

*4 this mean value is based on the 10 possible categories of income, in Euros (<500, 500 to>1000, …, 4000 to >4500, >4499). Due to the last category, the actual mean income is underestimated.

*5 Continuous Household Budget surveys (LWR) 2014; *6 low = no qualification or Volks- or Hauptschulabschluss (year 9 lower secondary school certificate); medium = polytechnic secondary school (Polytechnische Oberschule; POS), Real- or Mittelschulabschluss (year 10 lower secondary school certificate); high = Abitur, Fachabitur (secondary school certification, allows entrance to a university);

*7 numbers refer to number of households, not number of persons per household; *8 numbers refer to the population over 18; *9 Microcensus 2013

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as relative and absolute frequencies and, in part, as extrapolated absolute frequencies relative to the total population, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) (ebox).

eBOX.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as relative and absolute frequencies and, in part, as extrapolated absolute frequencies relative to the total population in Germany, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). They were based on a total population of 71 million people over 14 years, using the population statistics of the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) of 31 December 2014 (34). For some questions, a stratified presentation was made according to certain demographic or use-related characteristics. Unless otherwise stated, a design weight developed by Forsa was used for all the key figures shown, to take into account the different likelihood of telephone accessibility of certain groups of people. The relative and absolute frequencies of e-cigarette use were also shown either unweighted or weighted for education with the aid of microcensus data. The demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in eTable 3, together with the current figures from the German population for comparison. As our approach was exploratory, no tests were carried out for specific groups. The frequency of use and consumption of nicotine-containing liquids are shown in eTables 5 and 6. Statistical evaluations were done with IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

A total of 4002 persons were interviewed, comprising 48.8% men and 51.2% women (table 1). Of the respondents, 24.5% were active smokers, 34.0% had never smoked, 15.7% had tried smoking, and 25.3% were ex-smokers (table 1). 1.4% of the respondents regularly used electronic cigarettes, which is equivalent to one million people living in Germany over the age of 14 (95% CI [0.75, 1.25]). A further 2.2% had regularly used e-cigarettes in the past (1.55 million [1.25; 1.9]). The number of ever users was 11.8% (8.4 million [7.7, 9.1]), whereby the majority of them (70%) had only tried out e-cigarettes (table 1).

Table 1. Use of electronic cigarettes in Germany in 2016 in the total population, stratified based on use of tobacco products.

| Characteristic |

N (column percent) |

Have tried e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Former user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Current user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Ever user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Never user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

No response (%) [95% CI] |

|

| Germany 2016 weighted with design weight*1 |

4002 | 329 (8.2) [7.4; 9.1] |

88 (2.2) [1.8; 2.7] |

56 (1.4) [1.1; 1.8] |

473 (11.8) [10.8; 12.9] |

3 524 (88.1) [87.0; 89.0] |

5 (0.1) [0.0; 0.3] |

|

| Extrapolated to the total population in Germany (in thousands)*2 |

71 000 | 5800 [5250; 6500] |

1550 [1250; 1900] |

1 000 [750–1200] |

8400 [7650–9100] |

62 500 [61 850–64 250] |

– | |

| Weighted with design weights and educational level weights |

4002 | 346 (8.6) [7.8; 9.6] |

86 (2.1) [1.7; 2.7] |

68 (1.7) [1.3; 2.2] |

500 (12.5) [11.5; 13.6] |

3500 (87.4) [86.4; 88.5] |

3 (0.1) [0.0; 0.2] |

|

| Random sample unweighted | 4002 | 262 (6.5) [5.8; 7.4] |

77 (1.9) [1.5; 2.4] |

62 (1.5) [1.2; 2.0] |

401 (10.2) [9.1; 11.0] |

3594 (89.8) [88.8; 90.7] |

7 (0.2) [0.1; 0.4] |

|

| Use of tobacco products | Never | 1360 (34.0) |

26 (1.9) [1.3; 2.8] |

4 (0.3) [0.1; 0.8] |

1 (0.1) [0.0; 0.4] |

31 (2.3) [1.6; 3.2] |

1329 (97.7) [96.8; 98.5] |

0 [0.0; 0.3] |

| Have tried smoking |

627 (15.7) |

45 (7.2) [5.3; 9.5] |

7 (1.1) [0.5; 2.3] |

1 (0.2) [0.0; 0.9] |

53 (8.5) [6.4; 10.9] |

574 (91.5) [89.1; 93.6] |

0 [0.0; 0.6] |

|

| Quit smoking before 2010 |

798 (19.9) |

14 (1.8) [0.9; 2.9] |

0 [0.0; 0.5] |

0 [0.0; 0.5] |

14 (1.8) [0.1; 2.9] |

783 (98.2) [96.9; 99.0] |

0 [0.0; 0.5] |

|

| Quit smoking in 2010 or later |

214 (5.4) |

23 (10.6) [6.9; 15.7] |

18 (8.3) [5.1; 13.0] |

12 (5.6) [2.9; 9.6] |

53 (24.5) [19.1; 31.1] |

163 (76.2) [70.0; 81.7] |

0 [0.0; 1.7] |

|

| Smoker | 980 (24.5) |

220 (22.4) [19.9; 25.2] |

59 (6.0) [4.6; 7.7] |

42 (4.3) [3.1; 5.8] |

321 (32.7) [29.8; 35.8] |

660 (67.3) [64.3; 70.3] |

0 [0.0; 0.4] |

|

| No response | 23 (0.6) |

2 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 3 (13.0) | 15 (65.2) | 5 (2.2) | |

| Use of tobacco products, extrapolated to total population in Germany (in thousands)*2/*3 |

Never | 24 150 | – | 50 [0; 150] |

0 [0; 50] |

550 [350; 750] |

– | – |

| Quit smoking in 2010 or later |

3850 | – | 300 [200; 450] |

200 [100; 350] |

950 [700; 1150] |

– | – | |

| Smoker | 17 400 | – | 1050 [800; 1300] |

750 [500; 950] |

5700 [5200; 6200] |

– | – |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons.

*1 N = 4002 individuals 14 years or older

*2 for extrapolation, a population of 71 million was used. To avoid a false impression of precision, numbers are rounded off to 50 000

*3 only selected groups are shown

95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Distinct differences in the use of e-cigarettes were found with respect to tobacco product consumption (table 1). Specifically, e-cigarettes had been used by 32.7% of ever smokers (5.7 million, [5.2, 6.2]) but only by 2.3% of never smokers. These differences are even more pronounced when analyzing the participant’s regular consumption of e-cigarettes stratified for smoker status: 6.0% of current smokers have regularly used e-cigarettes in the past, as compared to 0.3% of never smokers. Further, 4.3% of current smokers, but only 0.1% of never smokers, used e-cigarettes at the time of the survey. Former smokers who had quit smoking before 2010 had the lowest prevalence of all groups studied: 1.8% of this user group had tried e-cigarettes, but none were regular users. In contrast, 24.5% of former smokers who had quit smoking in 2010 or later were ever users of e-cigarettes, with 8.3% former regular users of e-cigarettes and 5.6% current users of e-cigarettes.

The use of e-cigarettes clearly differed according to sex: 15% of men, and 8% of women, were ever users (table 2). Blue collar workers showed a distinct above-average use. For school students, the proportion of have-tried and former users was above average, while the proportion of current users was low. Overall, there was a clear dependency on age, with the age group 20 to 39 years the most frequently represented.

Table 2. Use of electronic cigarettes in Germany in 2016.

| Variable | Characteristic |

Total (column percent) |

Have tried e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Former regular user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Current regular user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Ever user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

Never user e-cigarettes (%) [95% CI] |

| Sex | Male | 1951 (48.8) |

199 (10.2) [8.9; 11.6] |

56 (2.9) [2.2; 3.7] |

38 (2.0) [1.4; 2.7] |

293 (15.0) [13.5; 16.7] |

1654 (84.8) [83.1; 86.3] |

| Female | 2051 (51.2) |

130 (6.3) [5.3; 7.5] |

32 (1.6) [1.0; 2.2] |

18 (0.9) [0.5; 1.4] |

180 (8.8) [7.6; 10.1] |

1871 (91.2) [89.9; 92.4] |

|

| Age | 14–19 years | 330 (8.2) |

46 (13.9) [8.2; 18.2] |

18 (5.5) [3.3; 8.5] |

3 (0.9) [0.2; 2.6] |

67 (20.3) [16.1; 25.1] |

263 (79.7) [75.0; 83.9] |

| 20–39 years | 1051 (26.3) |

169 (16.1) [13.9; 18.4] |

46 (4.4) [3.2; 5.8] |

25 (2.4) [1.6; 3.5] |

240 (22.8) [20.3; 25.5] |

809 (77.0) [74.3; 79.5] |

|

| 40–59 years | 1370 (34.2) |

85 (6.2) [5.0; 7.6] |

20 (1.5) [0.9; 2.2] |

24 (1.8) [1.1; 2.6] |

129 (9.4) [7.9; 11.1] |

1239 (90.4) [88.8; 91.9] |

|

| ≥ 60 years | 1252 (31.3) |

29 (2.3) [1.6; 3.3] |

4 (0.3) [0.1; 0.8] |

4 (0.3) [0.1; 0.8] |

37 (3.0) [2.1; 4.1] |

1214 (97.0) [95.9; 97.8] |

|

| Household income (in €) |

up to 1500 | 668 (16.7) |

80 (12.1) | 22 (3.3) | 10 (1.5) | 112 (16.8) | 555 (83.1) |

| 1500 up to 3000 |

1113 (27.8) |

85 (7.6) | 25 (2.2) | 15 (1.3) | 125 (11.2) | 987 (88.7) | |

| ≥ 3000 | 1216 (30.4) |

102 (8.4) | 23 (1.9) | 24 (2.0) | 149 (12.3) | 1066 (87.7) | |

| No response | 1006 (25.1) |

62 (6.2) | 18 (1.8) | 7 (0.7) | 87 (8.6) | 916 (91.1) | |

| Formal education level* |

Low | 690 (17.2) |

35 (5.1) | 11 (1.6) | 15 (2.2) | 61 (8.8) | 629 (91.2) |

| Medium | 1149 (28.7) |

137 (11.9) | 19 (1.7) | 16 (1.4) | 172 (15.0) | 977 (85.0) | |

| High | 1771 (44.2) |

124 (7.0) | 40 (2.3) | 20 (1.1) | 184 (10.4) | 1584 (89.4) | |

| Professional position |

Self-employed | 246 (6.1) |

16 (6.5) [3.8; 10.4] |

9 (3.7) [1.7; 6.8] |

5 (2.0) [0.1; 4.7] |

30 (12.2) [8.4; 17.0] |

216 (87.8) [83.1; 91.6] |

| Civil servant | 157 (3.9) |

10 (6.4) [3.1; 11.4] |

1 (0.6) [0.0; 3.5] |

1 (0.6) [0.0; 3.5] |

12 (7.6) [4.0; 13.0] |

145 (92.4) [87.0; 96.0] |

|

| Employee | 1334 (33.3) |

124 (9.3) [7.8; 11.0] |

36 (2.7) [1.9; 3.7] |

26 (1.9) [1.3; 2.8] |

186 (13.9) [12.1; 15.9] |

1145 (85.5) [83.8; 87.7] |

|

| Laborer | 218 (5.4) |

31 (14.2) [9.9; 19.6] |

14 (6.4) [3.6; 10.5] |

10 (4.6) [2.2; 8.3] |

55 (25.2) [19.6; 31.5] |

163 (74.8) [68.5; 80.4] |

|

| University student/ apprentice | 225 (5.6) |

45 (20.0) [15.0; 25.8] |

0 [0.0; 1.6] |

0 [0.0; 1.6] |

45 (20.0) [15.0; 25.8] |

180 (80.0) [74.2; 85.0] |

|

| Student | 270 (6.7) |

28 (10.4) [7.0; 14.6] |

16 (5.9) [3.4; 9.5] |

2 (0.7) [0.0; 2.7] |

46 (17.0) [12.8; 22.1] |

224 (83.0) [77.9; 87.3] |

|

| Retired | 1033 (25.8) |

32 (3.1) [2.1; 4.4] |

3 (0.3) [0.0; 0.8] |

3 (0.3) [0.0; 0.8] |

38 (3.7) [2.6; 5.0] |

994 (96.2) [94.9; 97.3] |

|

| Other | 485 (12.1) |

43 (8.9) [6.5; 11.8] |

8 (1.6) [0.8; 3.2] |

6 (1.2) [0.5; 2.7] |

57 (11.8) [9.0; 15.0] |

428 (88.2) [85.0; 91.0] |

Distinctions between different socio-economical groups. Weighted with design weight. “No response” values of less than 5% are not shown. As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons.

*low = no qualification or Volks- or Hauptschulabschluss (year 9 lower secondary school certificate); medium = polytechnic secondary school (POS), Real- or Mittelschulabschluss (year 10 lower secondary school certificate); high = Abitur, Fachabitur (secondary school certification, allows entrance to a university). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

The main reason for use given by ever users was “curiosity” (59.5%), followed by “quitting tobacco use or nicotine use” (29.1%), “complement to smoking” (7.8%), and “other reasons” (2.1%) (for instance, taste and lower price were mentioned) (Table 3). Regular e-cigarette users gave the reason for use as “quitting tobacco use or nicotine use” (52%), “complement to smoking” (25%), and “curiosity” (12.5%). Even among smokers, the main reason for regular use was the desire to quit smoking or nicotine use (46%). Among young people, curiosity was the strongest reason for use of e-cigarettes (73%).

Table 3. Reasons for use of e-cigarettes in selected socio-demongraphic groups.

| Variable | Characteristic | Stratified |

Total (n) |

To quit tobacco use/ nicotine use (%) [95% CI] |

As complement to tobacco use (%) [95% CI] |

Curiosity (%) [95% CI] |

Other (%) [95% CI] |

No response (%) [95% CI] |

| Total (%) |

Total | 474 | 138 (29.1) [25.1; 33.4] |

37 (7.8) [5.6; 10.6] |

282 (59.5) [54.9; 64.0] |

10 (2.1) [1.0; 3.9] |

7 (1.5) [0.6; 3.0] |

|

| Tried it out | 330 | 74 (22.4) [18.0; 27.3] |

15 (4.5) [2.6; 7.4] |

233 (70.6) [65.4; 75.5] |

2 (0.6) [0.1; 2.2] |

6 (1.8) [0.7; 3.9] |

||

| Former user |

88 | 35 (39.8) [29.5; 50.8] |

8 (9.1) [4.1; 17.1] |

42 (47.7) [37.0; 58.7] |

2 (2.3) [0.3; 8.0] |

1 (1.1) [0.0; 6.2] |

||

| Current user | 56 | 29 (51.8) [38.0; 65.3] |

14 (25.0) [14.4; 38.4] |

7 (12.5) [5.2; 24.1] |

6 (10.7) [4.3; 21.9] |

0 [0.0; 6.4] |

||

| Use of tobacco products (%) | Smoker | Total | 320 | 103 (32.2) [27.1; 37.5] |

30 (9.4) [6.4; 13.1] |

176 (55.0) [49.4; 60.5] |

9 (2.8) [1.3; 5.3] |

2 (0.6) [0.0; 2.2] |

| Tried it out | 220 | 57 (25.9) [20.3; 32.2] |

12 (5.5) [2.9; 9.3] |

148 (67.3) [60.6; 73.4] |

1 (0.5) [0.0; 2.5] |

2 (0.9) [0.0; 3.2] |

||

| User* | 100 | 46 (46.0) [36.0; 56.3] |

18 (18.0) [11.0; 27.0] |

28 (28.0) [19.5; 37.9] |

8 (8.0) [3.5; 15.2] |

0 [0.0; 3.6] |

||

| Quit smoking in or after 2010 |

Total | 53 | 20 (37.7) [24.8; 52.1] |

3 (5.7) [1.2; 15.7] |

29 (54.7) [40.5; 68.4] |

0 [0.0; 6.7] |

1 (1.9) [0.0; 10.1] |

|

| Tried it out | 23 | 4 (17.4) [5.0; 38.8] |

1 (4.3) [0.0; 22.0] |

18 (78.3) [56.3; 92.4] |

0 [0.0; 14.8] |

0 [0.0; 14.8] |

||

| User* | 30 | 16 (53.3) [34.3; 71.7] |

2 (6.7) [0.1; 22.1] |

11 (36.7) [20.0; 56.1] |

0 [0.0; 11.6] |

1 (3.3) [0.0; 17.2] |

||

| Currentuser | 12 | 9 (75.0) [42.8; 94.5] |

1 (8.3) [0.2; 28.5] |

2 (16.6) [2.1; 48.4] |

0 [0.0; 26.5] |

0 [0.0; 26.5] |

||

| Quit smoking before 2010 | Total | 15 | 3 (20.0) [4.3; 48.1] |

0 [0.0; 21.8] |

11 (73.3) [0.0; 21.8] |

0 [0.0; 21.8] |

1 (6.7) [0.2; 32.0] |

|

| Have tried smoking |

Total | 53 | 7 (13.2) [5.5; 25.3] |

0 [0.0; 6.7] |

46 (86.8) [74.7; 94.5] |

0 [0.0; 6.7] |

0 [0.0; 6.7] |

|

| Never smoker | Total | 32 | 7 (21.9) [9.3; 40.0] |

3 (9.4) [2.0; 25.0] |

18 (56.3) [37.7; 73.6] |

1 (3.1) [0.0; 16.2] |

3 (9.4) [2.0; 25.0] |

|

| Age group (%) | 14–19 years | 67 | 10 (14.9) | 5 (7.5) | 49 (73.1) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.0) | |

| 20–39 years | 238 | 70 (29.4) | 14 (5.9) | 149 (62.6) | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| 40–59 years | 129 | 50 (38.8) | 15 (11.6) | 60 (46.1) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.3) | ||

| ≥ 60 years | 37 | 6 (16.2) | 2 (5.4) | 24 (64.9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (8.1) | ||

| Sex (%) | Male | 292 | 76 (26.0) | 28 (9.6) | 180 (61.6) | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Female | 181 | 62 (34.3) | 8 (4.4) | 101 (55.8) | 6 (3.3) | 4 (2.2) |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons.

* former and current regular use. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Of all respondents, 3.2% could imagine trying e-cigarettes in the future, and 0.7% could imagine regularly using them. Among smokers, these percentages were 11.8% and 1.5%, respectively. The percentage among young people also was higher for trying e-cigarettes in the future (8.4%) but not for becoming a regular user (0.4%) (table 4).

Table 4. Potential future use of e-cigarettes in the total population and in selected groups.

| Variable | Characteristics |

Total (n) |

Yes, would try it | Yes, would use it |

No, would not use it |

No response |

| Total (%) | 3525 | 114 (3.2) | 25 (0.7) | 3374 (95.7) | 12 (0.3) | |

| Use of tobacco products (%) | Smoker | 661 | 78 (11.8) | 18 (1.5) | 557 (84.3) | 8 (1.2) |

| Quit smoking in 2010 or later | 163 | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 161 (98.8) | 0 | |

| Quit smoking before 2010 | 784 | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.2) | 774 (98.7) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Tried out smoking | 574 | 16 (2.7) | 3 (0.5) | 555 (96.7) | 0 | |

| Never smoker | 1329 | 12 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 1315 (98.9) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Age group (%) | 14–19 years | 263 | 22 (8.4) | 1 (0.4) | 234 (88.9) | 6 (2.3) |

| 20–39 years | 808 | 36 (4.5) | 6 (0.8) | 766 (94.8) | 0 | |

| 40–59 years | 1238 | 34 (2.7) | 16 (1.3) | 1186 (95.8) | 2 (0.2) | |

| ≥ 60 years | 1214 | 21 (1.7) | 2 (0.2) | 1187 (97.8) | 4 (0.3) | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 1654 | 69 (4.2) | 18 (1.1) | 1555 (94.0) | 12 (0.7) |

| Female | 1871 | 45 (2.4) | 7 (0.4) | 1819 (97.2) | 0 |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons

For potential harm, 20.7% of respondents believed e-cigarettes to be less dangerous, 46.3% equally dangerous, and 16.1% more dangerous, than conventional cigarettes, while 17.0% did not give a response for this. Finally, 25.5% of current smokers believed that e-cigarettes are less dangerous than conventional cigarettes (etable 4).

eTable 4. Perception of danger of e-cigarettes as compared to conventional cigarettes in the total population and in selected groups.

| Variable | Characteristic |

Less dangerous than tobacco cigarettes |

Equally dangerous as tobacco cigarettes |

More dangerous than tobacco cigarettes |

No response |

Total (n) |

| Total (%) | 828 (20.7) | 1852 (46.3) | 644 (16.1) | 679 (17.0) | 4002 | |

| Ever use of e-cigarettes (%) |

User | 190 (40.2) | 184 (38.9) | 59 (12.5) | 30 (6.3) | 473 |

| Never user | 636 (18.0) | 1666 (47.3) | 575 (16.3) | 647 (18.4) | 3524 | |

| Smoker status (%) | Smoker | 250 (25.5) | 444 (45.3) | 156 (15.9) | 131 (13.4) | 981 |

| Quit smoking in 2010 or later | 68 (31.8) | 94 (43.9) | 36 (16.8) | 16 (7.5) | 214 | |

| Quit smoking before 2010 | 127 (15.9) | 376 (47.1) | 128 (16.0) | 167 (20.9) | 798 | |

| Tried out smoking | 123 (19.6) | 306 (48.8) | 102 (16.3) | 96 (15.3) | 627 | |

| Never smoker | 255 (18.8) | 626 (46.0) | 219 (16.1) | 261 (19.2) | 1361 | |

| Age group (%) | 14–19 years | 117 (35.5) | 131 (39.7) | 70 (21.2) | 12 (3.0) | 330 |

| 20–39 years | 249 (23.7) | 530 (50.5) | 171 (16.3) | 100 (9.5) | 1050 | |

| 40–59 years | 296 (21.6) | 656 (47.9) | 182 (13.3) | 235 (17.2) | 1369 | |

| ≥ 60 years | 165 (13.2) | 535 (42.7) | 221 (17.6) | 332 (26.5) | 1253 | |

| Formal education level* (%) |

Low | 89 (12.9) | 290 (42.1) | 159 (23.1) | 151 (21.9) | 689 |

| Medium | 224 (19.5) | 536 (46.6) | 194 (16.9) | 195 (17.0) | 1149 | |

| High | 390 (22.0) | 882 (49.8) | 215 (12.1) | 284 (16.0) | 1771 | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 492 (25.2) | 802 (41.1) | 309 (15.8) | 348 (17.8) | 1951 |

| Female | 336 (16.4) | 1050 (51.2) | 334 (16.3) | 330 (16.1) | 2050 |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons.

*low = no qualification or Volks- or Hauptschulabschluss (year 9 lower secondary school certificate); medium = polytechnic secondary school (Polytechnische Oberschule; POS),

Real- or Mittelschulabschluss (year 10 lower secondary school certificate); high = Abitur, Fachabitur (secondary school certification, allows entrance to a university)

Discussion

Our survey shows that nearly every eighth resident of Germany has tried e-cigarettes. Compared to studies from the years 2014 and 2015, this is a considerable increase (between 50% and 100%) of the group of ever users (2, 5, 6) (etable 1), although some of this increase could result from methodological differences between surveys. However, compared to the current results from the UK, regular e-cigarette use is rare in Germany (etable 1). A Europe-wide study in 2014 concluded that Germany had a below-average number of users as compared to the rest of Europe (5). The lower number of users is probably due at least in part to the percentage of smokers who use e-cigarettes. For instance, we found that 32.7% of smokers in Germany have ever used e-cigarettes, which is in stark contrast to the finding that 64% of smokers in the UK have ever used e-cigarettes (7). In 2015, the ever use of e-cigarettes among tobacco smokers was 30% in Europe but 19% in Germany (5).

The results of our study provide limited initial information about the potential benefits of e-cigarettes as a smoking reduction or cessation aid, and their potential risk as an entry into tobacco use.

According to our investigation, e-cigarettes are used on a regular basis almost exclusively by smokers and ex-smokers. Almost half of the smokers who used e-cigarettes gave the reason for use as quitting tobacco and nicotine use, while a quarter of smokers see e-cigarettes as a complementary product to tobacco smoking. Among ex-smokers who quit in 2010 or later, between 100 000 and 350 000 persons regularly used e-cigarettes, and between 200 000 and 450 000 had used them in the past. The question then arises of whether these regular e-cigarette users gave up smoking with the help of e-cigarettes. Indeed, 75% of the current e-cigarette users (and 50% of all regular users) reported quitting smoking as the main reason for their e-cigarette use (Table 3). While this could indicate that e-cigarettes are relevant tobacco cessation aids, we cannot rule out that additional aids were used.

Additionally, our study is limited in the extent it can address whether or not e-cigarettes act as a gateway to smoking.

Only very few never smokers have tried out e-cigarettes, and almost none of them are currently regular users. In fact, there were no regular users even among ex-smokers who had quit before 2010 or among those who had only tried out smoking. Further, our data do not provide any indications that non-smokers who test e-cigarettes are more likely to become regular users.

Experimental use of e-cigarettes is more common among never smokers in the student and young people group than in other age groups (data not shown). However, regular use is rarer, and “curiosity” as the reason for use is more frequently stated than for other groups. An indication of a possible addiction potential of electronic cigarettes is the frequency of use (etable 5). Of the 6.3% of young people who regularly use e-cigarettes, nearly all (90.5%) use e-cigarettes weekly or less frequently. Thus, they use e-cigarettes much less frequently than other regular users. The use of a nicotine-containing liquid is also less frequent than in other groups (etable 6). While this does not point to an immediate addiction potential of e-cigarettes, it can not be ruled out that, following infrequent use of e-cigarettes, the users directly move into the group of tobacco users.

eTable 5. Use of nicotine liquids among all e-cigarette users and in selected groups.

| Variable | Characteristics |

Total (n) |

Only with nicotine |

Mainly with nicotine |

Mainly without nicotine |

Only without nicotine |

No response |

| Total (%) | 473 | 143 (30.2) | 121 (25.6) | 83 (17.5) | 72 (15.2) | 54 (11.4) | |

| Smoker status (%) | Smoker | 320 | 117 (36.6) | 96 (30.0) | 45 (14.1) | 37 (11.6) | 25 (7.8) |

| Quit smoking in 2010 or later |

52 | 13 (25.0) | 16 (30.8) | 6 (11.5) | 7 (13.5) | 10 (19.2) | |

| Quit smoking before 2010 |

14 | 5 (35.7) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Have tried smoking | 53 | 8 (15.1) | 7 (13.2) | 15 (28.3) | 11 (20.7) | 12 (22.6) | |

| Never smoker | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 0 | 15 (46.9) | 13 (40.6) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Age group (%) | 14–19 years | 68 | 6 (8.8) | 14 (20.6) | 21 (30.9) | 24 (35.3) | 3 (0.4) |

| 20–39 years | 239 | 77 (32.2) | 66 (27.6) | 44 (18.4) | 24 (10.0) | 28 (11.7) | |

| 40–59 years | 128 | 48 (37.5) | 37 (28.9) | 11 (8.6) | 20 (15.6) | 12 (9.4) | |

| ≥ 60 years | 37 | 11 (29.7) | 4 (10.8) | 7 (18.9) | 4 (10.8) | 11 (29.7) | |

| Use(%) | Have tried it | 329 | 101 (30.7) | 70 (21.3) | 59 (17.9) | 49 (14.9) | 50 (15.2) |

| Former user | 88 | 22 (25.0) | 31 (35.2) | 17 (19.3) | 15 (17.0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Current user | 55 | 19 (34.5) | 20 (36.4) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (14.5) | 0 |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons.

eTable 6. Frequency of e-cigarette use among former and current users and in selected groups.

| Variable | Characteristic | Total (n) | Several times daily | Daily | Weekly | Less frequently |

| Total (%) | 144 | 57 (39.6) | 12 (8.3) | 21 (14.6) | 54 (37.5) | |

| User (%) | Former | 88 | 35 (39.8) | 8 (9.9) | 8 (9.9) | 37 (42.0) |

| Current | 56 | 22 (39.3) | 4 (7.1) | 13 (23.2) | 17 (30.4) | |

| Smoker status (%) | Smoker | 101 | 44 (43.6) | 6 (5.9) | 14 (13.9) | 37 (36.6) |

| Quit in 2010 or later |

29 | 13 (44.8) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (10.3) | 10 (34.5) | |

| Quit before 2010 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Have tried smoking |

8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Never smoker | 6 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | |

| Age group (%) | 14–19 years | 21 | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 6 (28.6) | 13 (61.9) |

| 20–39 years | 71 | 29 (40.1) | 7 (9.9) | 9 (12.7) | 26 (36.6) | |

| 40–59 years | 44 | 25 (56.8) | 4 (9.1) | 5 (11.4) | 10 (22.7) | |

| ≥ 60 years | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (62.5) |

As a result of weighting, summation of absolute frequencies may contain round-off errors, in the range of 1 to 2 persons

The results of the respondents’ assessments about the dangers of e-cigarettes were surprising. Only one-fifth of Germans believe that e-cigarettes are less dangerous than tobacco cigarettes. Using e-cigarettes rather than tobacco cigarettes clearly reduces the risk for disease, although the degree of risk reduction has not yet been scientifically determined (2, 12, 35– 37). In the UK, the risk of e-cigarette consumption is perceived differently, with 73% of the total population stating that e-cigarettes are less dangerous (7). It is possible that the relatively low consumption in Germany is related to its suspected health risks. Only a small percentage of smokers in Germany can imagine trying out e-cigarettes in the future.

Strengths and limitations

The present study examined the prevalence of e-cigarette consumption in Germany in a large, population-based sample. It was integrated into a multi-topic survey that was not focused on health issues, which perhaps evoked a more honest response than single-topic surveys. Also, for the first time, we have examined ex-smokers who had recently quit smoking (in 2010 or later) as an individual group.

As our study was cross-sectional, it cannot determine cause and effect. The survey also recorded past events, which presents the possibility for memory errors to be included. Indeed, a few implausible values ??can be found in the study. For example, some people who referred to themselves as never smokers claimed to use e-cigarettes with the aim of quitting smoking (Table 3).

Telephone surveys of the entire population are subject to certain forms of selection error. Potentially poorer telephone availability among certain groups of people was taken into account by including a design weight. Indeed, our study was strengthened by the fact that our socio-demographic data correspond to that of the entire population, with the exception of the formal education levels and the information given for never smoking. With respect to formal education, these kind of surveys often have a typical selection error due to the fact that people with a higher educational degree are more likely to take part in surveys than those with a lower degree. However, a supplementary analysis in which education levels were weighted did not significantly change the resulting percentages (table 1). The percentage of never smokers (34%) is significantly lower in our study than in the microcensus (56.2%). This difference is probably explained by our category of “have tried smoking”, which does not exist in the microcensus (38). No response rate could be determined in this study, as it was integrated into a rolling survey which, for technical reasons, had no defined start or end. Finally, it is possible that e-cigarette users have a different participation behavior than non-users, which could lead to a non-response bias.

Conclusion

With one million regular users in Germany, the consumption of e-cigarettes is gaining in relevance. Users are almost exclusively smokers or ex-smokers who quit smoking in 2010 or later. In order to clarify whether e-cigarettes are useful for smoking cessation, or whether they instead provide a gateway to smoking, longitudinal studies are necessary.

Key Messages.

Our representative study found that regular users of electronic cigarettes in Germany are almost exclusively either smokers or ex-smokers who had quit in 2010 or later.

The number of regular e-cigarette users has risen sharply since 2014.

In Germany, around 1 million people use e-cigarettes regularly.

Between 100 000 and 350 000 ex-smokers use e-cigarettes regularly in Germany.

More than 60% of the German population perceive e-cigarettes to be as dangerous or more dangerous than tobacco cigarettes.

eFigure.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the institutional budget of the Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemology, and Informatics of Universitätsmedizin Mainz

Translated from the original German by Veronica A. Raker, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Nowak D, Jörres RA, Rüther T. E-cigarettes—prevention, pulmonary health, and addiction. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:349–355. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ) Tabakatlas Deutschland 2015. www.dkfz.de/de/tabakkontrolle/download/Publikationen/sonstVeroeffentlichungen/Tabakatlas-2015-final-web-dp-small.pdf (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patent. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette) www.google.com/patents/US3200819?hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consumer Advocates for Smoke Free Alternatives Association. E-cigarette history. www.casaa.org/E-cigarette_History.html (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Commision. Special eurobarometer 429“attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes”. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider S, Görig T, Diehl K. Die E-Zigarette - Bundesweite Daten zu Bekanntheit, Nutzung und Risikowahrnehmung ASU Arbeitsmed Sozialmed Umweltmed 2015 50. www.asu-arbeitsmedizin.com/ (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics Dataset. E-cigarette use in Great Britain 2015 Opinion and lifestyle survey 2016. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/drugusealcoholandsmoking/datasets/ecigaretteuseingreatbritain (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andler R, Guignard R, Wilquin JL, Beck F, Richard JB, Nguyen-Thanh V. Electronic cigarette use in France in 2014. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States 2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amtsblatt der Europäischen Union. Richtlinie 2014/40/EU des europäischen Parlaments und des Rates 2014. www.ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/dir_201440_de.pdf (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Die Bundesregierung. Kinder- und Jugendschutz: Besserer Schutz vor E-Shishas 2016. www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Artikel/2015/11/2015_11-04-e-zigaretten-shishas.html (last accessed on 17 October 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, et al. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20:218–225. doi: 10.1159/000360220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pankow JF, Strongin RM, Peyton DH. Formaldehyde from e-cigarettes—it’s not as simple as some suggest. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015;110:1687–1688. doi: 10.1111/add.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsalinos KE, Voudris V, Poulas K. E-cigarettes generate high levels of aldehydes only in “dry puff” conditions. Addict Abingdon Engl Correspondence. 2015;110:1861–1862. doi: 10.1111/add.12942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2015;17:127–133. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. CD010216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:116–128. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob Control 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705 (epub ahead of print) doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner KE. Frequency of e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking by American students in 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pesko MF, Hughes JM, Faisal FS. The influence of electronic cigarette age purchasing restrictions on adolescent tobacco and marijuana use. Prev Med. 2016;87:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA) Elektrische Zigaretten (E-Zigaretten) Gesundheitsgefahren und Risken 2013. www.bzga.de/pdf.php?id=4c89a7dd18a809e 708216dd31e9a4479 (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aktionsbündnis Nichtrauchen e. V. (ABNR) Faltblatt zum Welt-Nichtrauchertag 2015 “E-Zigaretten und E-Shishas: Chemie für die Lunge” 2015. www.abnr.de/files/abnr_broschu__re_positionspapier_webfassung-2.pdf (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aktionsbündnis Nichtrauchen e. V. (ABNR) Politische Forderungen. 6. E-Zigaretten und E-Shishas wirksam regulieren o.J. www.abnr.de/index.php?article_id=46 (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNeill A, Brose L, Calder R, Hitchman S, Hajek P, McRobbie H. E-cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England 2015. www.abnr.de/index.php?article_id=46 (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) Electronic cigarettes: a briefing for stop smoking services 2016. www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_electronic_cigarette_briefing.php (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Physicians Nicotine without smoke tobacco harm reduction. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0 (last accessed on 17 October 2016) London: 2016. A report by the tobacco advisory group of the Royal College of Physicians RCP. [Google Scholar]

- 27.ash. action on smoking and health ASH Briefing. Electronic cigarettes (also known as vapourisers) 2016. http://ash.org.uk/stopping-smoking/ash-briefing-on-electronic-cigarettes-2/ (last accessed on 17 October 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 28.ash. action on smoking and health Factsheet. www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_891.pdf (last accessed on 14 September 2016) Britain: 2016. use of electronic cigarettes (vapourisers) among adults in Great. [Google Scholar]

- 29.West R. Smoking toolkit study: protocol and methods 2006. www.smokinginengland.info/downloadfile/?type=sts-documents&src=4 (last accessed on 14 September. 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office for National Statistics. Opinions and Lifestyle (Opinions) Survey Information for clients 2015-16. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/products-and-services/opn/information-guide-2013-14.pdf (last accessed on 17 October 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arbeitsgemeinschaft ADM-Stichprobensysteme. Das ADM-Stichprobensystem für Telefonbefragungen. www.adm-ev.de/telefonbefragungen/ (last accessed on 17 October 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabler S, Häder S. Ein neues Stichprobendesign für telefonische Umfragen in Deutschland; In: Telefonstichproben in Deutschland 1998th ed. Opladen. :69–88. [Google Scholar]

- 33.ADM ADM-Forschungsprojekt ‚Dual-Frame-Ansätze’ 2011/ 2012. Forschungsbericht 2012. www.adm-ev.de/forschungsprojekte/ (last accessed on 17 October 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistisches Bundesamt Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit 2014 - Vorläufige Ergebnisse der. Bevölkerungsfortschreibung auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011, 2015. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/VorlBevoelkerungsfortschreibung.html (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, et al. E-cigarettes are less harmful than smoking. Lancet. 2016;387:1160–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee M, Capewell S. Electronic cigarettes: we need evidence, not opinions. Lancet. 2015;386 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.No authors listed. E-cigarettes: Public Health England’s evidence-based confusion. Lancet 2015; 386: 829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Statistisches Bundesamt: Mikrozensus – Fragen zur Gesundheit. Verteilung der Bevölkerung nach ihrem Rauchverhalten in Prozent. 2013, 2014. www.gbe-bund.de (last accessed on 14 September 2016) [Google Scholar]