Abstract

Although substance use continues to be a significant component of HIV risk among women worldwide, to date relatively little attention has been paid in research, services, or policy to substance-involved women (SIW). HIV acquisition for SIW stems from transmission risks directly related to substance use, as well as risks associated with sexual activity where power to negotiate risk and safety are influenced by dynamics of male partnerships, sex work, and criminalization (of both drug use and sex work), among other things. As such, HIV risk for such women resides as much in the environment—physical, social, cultural, economic, and political--in which drug use occurs as it does from transmission-related behaviors of individual women. To reduce HIV infections among SIW, it is important to specify the interaction of individual- and environmental-level factors, including, but not limited to those related to women's own substance use, that can and ought to be changed. This involves theorizing about the interplay of gender, substance use, and HIV risk and incorporating that theoretical understanding into intervention design and evaluation. A review of the published literature focused on HIV prevention among SIW revealed a general lack of theoretical and conceptual foundation specific to the gender-related and environmental drivers of HIV in this population. Greater theoretical linkages to intersectionality and syndemics approaches are recommended to better identify and target relevant mechanisms by which the interplay of gender dynamics and substance use potentiate the likelihood of HIV acquisition and transmission among SIW.

Keywords: HIV, substance use, women, theory

Introduction

Substance-involved women (SIW) are those engaged in or otherwise affected by drug and/or alcohol abuse. These women include those with a chemical dependency and/or who inject drugs, those whose male partners abuse drugs and/or alcohol, and women living in environments with a high prevalence of substance-dependent persons.1 Substance use continues to be a significant component of HIV risk among women worldwide,2 and in many locales HIV prevalence among SIW--and female injecting drug users (IDU) specifically--is higher than that of men.3 But relatively little attention has been paid to SIW throughout the course of the pandemic—whether in research, programs and services, or policy.4 Contributing to this are HIV transmission classifications that historically have lumped women together with men into the IDU category, or referred to heterosexual transmission risk independent of overlapping substance use-related risks. These categorizations have masked the dynamic interplay of gender (especially gender inequality and gendered power relations), substance use, and HIV risk in the lives of SIW.

Additionally, traditional approaches to HIV prevention, which have focused on reducing the frequency of HIV transmission-related behaviors (e.g., sharing drug injection equipment and engaging in condom-unprotected sex), are grounded in the assumption that individuals have sufficient autonomy to mitigate their HIV risk (e.g., by obtaining clean needles prior to injecting, and by using condoms).5 For the most part, they have not recognized how the unique HIV risk dynamics of SIW often limit such autonomy in a number of critical ways, including the psychological and physiological influences of substance use itself, and gender-related power dynamics, such as social norms enforcing men's dominance in sexual decision-making, tolerance of intimate partner violence, and limited economic opportunities for women.6

For SIW, the interaction of substance use and gender-related power dynamics have particularly damaging consequences that heighten vulnerability to HIV while inhibiting the ability to mitigate personal HIV risk. For example, male sex partners and/or pimps may frequently control both access to and administration of illicit drugs, such as heroine or crack cocaine (by holding the drugs, crack pipes or syringes, or by directly injecting women).6 These individuals may enforce rules and restrictions that woman must adhere to in exchange for access to drugs, resources for shelter and `safety', or to avoid arrest and prosecution, effectively creating a dependency both on the substance and on the persons controlling women's access.1 Additionally, women in environments with prevalent substance use and abuse are disproportionately affected by violence, sexual assault, related mental health challenges (e.g., depression and PTSD), and stigma associated with such experiences.1, 7 Combined there are a number of direct and indirect individual, relational, social, economic, and structural barriers that SIW face to engage in HIV prevention on their own behalves.8

While many of these substance use and gender-related power dynamics have been noted in the literature, it remains unclear the extent to which they have been integrated into conceptual models to explicate the individual, relational, social, economic, and structural pathways between risk and HIV infection, and, thereby, to inform HIV prevention efforts with SIW globally. To ascertain this, we undertook a comprehensive, narrative literature review of published observational and intervention studies involving HIV prevention among SIW to better understand how theory has been employed in this body of work. We were specifically interested in knowing how theory was used to articulate the gender and substance use risk dynamics believed to potentiate HIV risk among SIW in particular settings, and in identifying gaps and opportunities to advance theory-driven research that can strengthen HIV prevention in this population.

Methods

Between December 2014 and January 2015, we conducted two independent comprehensive searches in PubMed to identify HIV prevention observational and intervention research, focused on SIW since the start of the HIV epidemic. In both searches, terms related to HIV or AIDS, gender, and substance use (alcohol and drugs) were combined. Search 1 included additional terms to identify observational research (qualitative studies, observational studies, formative research); and, in an effort to elicit only female-focused studies, it excluded articles indexed as having male participants. Search 2 included additional terms to identify intervention studies (including randomized controlled trials) that may have targeted female-relevant risk dynamics. Both searches were restricted to articles with female samples age18 years and older and that were published in peer-reviewed journals. (See Search Strategy, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for search terms and study type definitions).

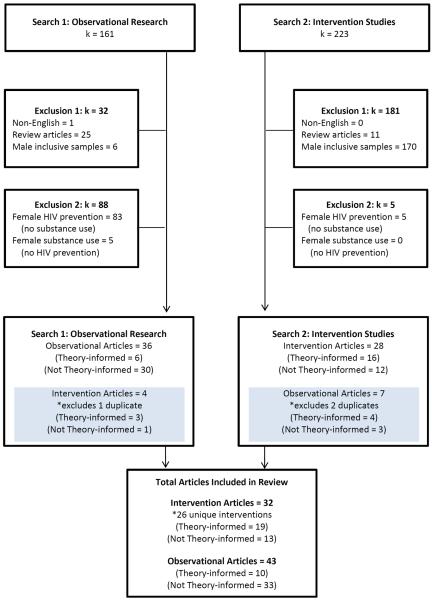

Details on the evaluation process for this review are provided in Figure 1, where `k' represents the number of articles. Across both searches, articles were excluded from review if they were not available in English (to ensure an accurate assessment of content by reviewers), did not focus on original research (e.g., were review articles or commentaries), and were not focused on cis (women who identify with the gender assigned at birth) and/or transgender women. We excluded studies with samples that were male only, or were male-inclusive focusing on substance users as a unified group with no distinct attention to women. HIV prevention articles that did not include SIW and substance use articles that did not focus on primary or secondary HIV prevention were further excluded. Articles appearing in both searches were de-duplicated (k = 3). This processes produced a final set of 69 unique HIV prevention studies (75 manuscripts total) focused on SIW for review.

Figure 1.

Articles reviewed for inclusion in the comprehensive narrative review (k = number of articles)

Our aim was to conduct a narrative review on the role theory or conceptual frameworks have played in global HIV prevention research with SIW. Narrative reviews focus on descriptive discussions of a body of literature, as compared to systematic reviews, which are more typically used to classify the type and magnitude of study outcomes.9 While a comprehensive search strategy was used, we did not systematically search databases beyond Pubmed or the grey literature to ensure an exhaustive search and may have missed relevant articles that were not indexed in Pubmed under our specified search terms. We acknowledge this as a potential limitation of our analysis.

Results

Of the 161 articles identified through Search 1, 37 (23.0%) met inclusion criteria for observational research targeting SIW; and an additional 4 articles (2.5%) met the inclusion criteria for intervention studies. As this search targeted female-only samples, relatively few studies were excluded for having male-only (k = 1) or male-inclusive (k = 6) target populations. Rather, most studies were excluded because their HIV prevention focus did not target substance involvement among women (k = 83, 51.6%). For example, 55 articles focused on vertical transmission-related issues (e.g., antiretrovirals for prevention of mother-to-child transmission, exclusive breast feeding practices, fertility desires, etc.) without examining substance use-related factors. Search 2 yielded 223 articles, of which 28 (12.6%) met inclusion criteria for HIV prevention intervention studies targeting SIW; and an additional 7 (3.1%) articles met the inclusion criteria for observational research. Most of the excluded intervention articles (76.2%) had male-only (k = 6) or male-inclusive (k = 164) target populations that did not address female-relevant risk dynamics. For the purposes of our subsequent analysis, we defined “theory-informed” studies (whether observational or intervention) as those that identified an explicit theory (or set of theories) that informed the research and analysis in some way—e.g., hypothesis development and testing, study design, intervention content, etc.

Geographic Scope of HIV Prevention Studies with Substance-involved Women

The articles that met inclusion criteria for review were somewhat limited in their geographic scope. The majority focused on the North American region, particularly the U.S., and to a lesser extent Asia. Our searches revealed relatively little work among SIW in Australia or Western Europe, which was surprising given that IDU drove HIV infections in these regions in the early years of the pandemic (and to some extent still does). Eastern Europe and Latin America also were under-represented (2 observational studies in Russia and 3 in Brasil), where both sex work and substance use (IDU, crack cocaine) substantially affect HIV risk among SIW. Notwithstanding the size of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, only 4 studies addressed sexual risk and substance use among female sex workers (South Africa, Rwanda and Kenya), the role of alcohol on shaping HIV risk among women attending informal drinking establishments (South Africa), and how HIV-positive women's male partners' alcohol use affected secondary prevention (Zambia). Only one study reported on HIV risk among substance-using women in the Middle East (Iran). Given that substance use continues to be a significant driver of HIV infections among women in Central and Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, it is surprising that so few studies from these regions appeared in our searches.

When we look at the theory-informed studies specifically (described further below), most –both observational (60%) and intervention (68.75%) –occurred in the U.S., with others taking place in Canada, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Australia, China, Russia, and South Africa. (See Tables 1 and 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for further details about study characteristics and references for the 75 published articles we reviewed.)

Table 1.

Theory-informed HIV Prevention Observational Research Focused on Substance Using and Substance-Involved Women

| SETTING | FEMALE SAMPLE | REVIEW INCLUSION CRITERIA | THEORETICAL FOCUS or §APPROACH | METHOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russia17 | N = 29 IDI FSW, FSW-IDU |

SU Type: IDU | Structural Violence | Qualitative |

| HIV Risk: Access to HIV/healthcare services | ||||

| Risk Level: Social, Economic, Structural | ||||

| South Africa18 | N = 560 Survey Women Attending Drinking Venues |

SU Type: Alcohol use | Syndemics | Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Alcohol use, IPV | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social, Structural | ||||

| China20 | N = 1,022 Survey FSW |

SU Type: Substance use | Social Norms Theory | Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States11 | N = 40 IDI 10 Ethnographic visits Exotic Dancers |

SU Type: Substance Use | HIV Risk Environment §Grounded Theory |

Qualitative |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Regulating SW at venue | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Economic, Structural | ||||

| United States12 | N = 8 FG Hispanic Females |

SU Type: Substance use | Syndemics (SAVA) | Qualitative |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Substance use, IPV | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Sex dyad, Social | ||||

| Canada19 | N = 46 women in FG Cis and Transgender Drug Using FSW |

SU Type: Illicit drug use | HIV Risk Environment Interconnected theories of violence (Everyday, Structural, & Symbolic) §Post-structural feminist critiques |

Qualitative |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug withdrawal, SW environments, Violence | ||||

| Risk Level: Sex dyad, Social, Structural | ||||

| United States15 | N = 30 Survey African American Drug Using Women |

SU Type: Drug use | HBM | Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual Risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States13 | N = 250 Survey At-risk Women with History of Childhood Neglect/Abuse |

SU Type: Drug use, Drug using family member | SCT, TRA, TPB, HBM | Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States14 | N = 349 Survey Women on Methadone |

SU Type: Enrolled in Methadone treatment | Stress & Coping Theory §Systems perspective (interpersonal dyads) |

Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Male partner's serostatus | ||||

| Risk Level: Sex dyad | ||||

| United States16 | N = 209 Survey Female IDU |

SU Type: IDU | TRA, TPB | Cross-Sectional |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual |

NOTE: (See Tables, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for citations regarding specific theories and guiding approaches).

Identifies a general approach to behavior change or a guiding framework/approach used in the analysis and/or interpretation of the data that does not specify theoretical mechanisms of HIV risk per se.

Sample size is in reference to data collection methods unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: IDI = In-depth interview; Survey = Self- or interviewer-administered quantitative measures; FG = Focus groups; SU Type = Type of substance use or substance involvement specified in the target population; IDU = Intravenous Drug User; FSW = Female Sex worker; IPV = Intimate partner violence; SW = Sex work; SAVA = Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS; SCT = Social Cognitive Theory; TRA = Theory of Reasoned Action, TpB = Theory of Planned Behavior, HBM = Health Belief Model.

Table 2.

Theory-informed HIV Prevention Intervention Studies Focused on Substance Using and Substance-Involved Women

| SETTING | FEMALE SAMPLE | REVIEW INCLUSION CRITERIA | THEORETICAL FOCUS or §APPROACH | STUDY NAME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico34, 35,a | N = 584 FSW-IDU |

SU Type: IDU | SCT, TRA §MI approach |

Mujer Mas Segura |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, IDU behaviors | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States23,b | N =521 Incarcerated Women |

SU Type: IDU, Substance use | AIDS Risk Reduction Model Syndemics |

Project Power |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Substance use, IPV | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social, Structural | ||||

| United States21,c | N = 548 Low-income Hispanic Women |

SU Type: Problem drinking | SCT §Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed |

SEPA |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Alcohol use, IPV | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States26 | N = 311 At-risk non-IDU Women |

SU Type: Non-IDU illicit drug use | SCT | Unity Study |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, HIV vaccine | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| Puerto Rico38,d | N = 100 At-risk Heterosexual Women |

SU Type: IDU and Crack use | Used theoretical concepts related to SCT, TRA, §MI approach | RReduC-PR |

| HIV Risk: Individualized risk-reduction plans | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States33,e | N = 366 HIV+ Women |

SU Type: Alcohol use | SCT Theory of Gender & Power |

The WiLLOW Program |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social | ||||

| South Africa36,f | N = 93 Black South African Cocaine Using FSW |

SU Type: Cocaine use, Alcohol use | SCT Theory of Gender & Power §Empowerment approach |

Women-focused HIV Prevention |

| HIV Risk: Sexual Risk, Substance use, Violence | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Sex dyad | ||||

| US Virgin Is.37 | N = 191 formative 20 pilot Indigent Substance Abusing Women |

SU Type: Substance abuse | SCT, HBM §Empowerment approach |

The Virgin Is. Women's Intervention |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social | ||||

| United States27 | N = 54 Drug using FSW |

SU Type: Heroin or Cocaine use | SCT §Economic Enhancement Framework |

JEWEL Project |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug use, Income options | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Economic | ||||

| United States28, 29 | N = 333 African American Drug Using Women |

SU Type: Active IDU and/or Crack use | SCT, TRA, TpB Transtheoretical Model Theory of Gender & Power |

HIP House |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug use, IDU behaviors | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social | ||||

| United States25 | N = 13 IDI 9 ethnography visits Cis and Transgender Homeless Women |

SU Type: Substance use |

§feminist Ethnography Social Network Theory |

Ladies' Night |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug use, Safety | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual, Social, Structural | ||||

| United States30 | N = 541 African American Drug Using Women |

SU Type: IDU and Crack use | Integrated behavior change models (TRA, SCT, HBM, SLT), using gendered themes to tailor content (i.e., cooking) | Miami Cares |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug risk behaviors | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States31, 32 (21 sites)g | N = 1,403 Drug Using Women |

SU Type: IDU and Crack use | HBM, SLT Fear Arousal Theory Social Influence Theory |

NIDA Cooperative Agreement |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug risk behaviors | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| Austrailia39,h | N = 92 Pregnant IDU on Methadone |

SU Type: Enrolled in Methadone treatment | Relapse Prevention Model Transtheoretical Model §Problem-solving strategies §MI approach |

CBT Relapse Prevention |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug use, IDU behaviors | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States24 | N = 145 Drug Abusing Women in Jail |

SU Type: Illicit drug use | SCT, HBM §Behavioral/cognitive skills §Problem-solving strategies §Social support & Help seeking §Empowerment approach |

Social Support Enhancement |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual | ||||

| United States22 | N = 91 Black and Hispanic Women on Methadone |

SU Type: Enrolled in Methadone treatment | SCT | Skills Building Group |

| HIV Risk: Sexual risk, Drug use | ||||

| Risk Level: Individual |

NOTE: (See Tables, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for citations regarding supporting articles, specific theories, and guiding approaches).

Identifies a general approach to behavior change or a guiding framework/approach used in the analysis and/or interpretation of the data that does not specify theoretical mechanisms of HIV risk per se.

Sample size is in reference to intervention participants unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: SU Type = Type of substance use or substance involvement specified in the target population; IDU = Intravenous Drug User; FSW = Female Sex worker; IDI = In-depth interview; IPV = Intimate partner violence; SCT = Social Cognitive Theory; TRA = Theory of Reasoned Action, MI = Motivational Interviewing, HBM = Health Belief Model, TpB = Theory of Planned Behavior, SLT = Social Learning Theory.

Comments regarding intervention development and/or descriptions obtained from our reviewed articles:

Intervention details and theoretical foci was abstracted from Vera et al. (2012).

Details on Project Power, as adapted from a CDC Evidence-based Intervention Project SAFE, was obtained from Fogel et al. (2014).

SEPA (Salud Educacion Promocion y Autocuidado) was adapted from a previous version of the study with low-income Latina women.

RReduC-PR (Risk Reduction Counseling – Puerto Rico) adapted from RESPECT-2.

Intervention details on WILLOW (women involved in life learning from other women) were abstracted from Wingood et al. (2004).

Intervention was adapted from work with crack using African American females in the United states.

Only used data from the 21 unspecified sites of the 23 cooperative agreement sites in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Brazil.

Intervention details abstracted from Baker et al. (1993).

How Theory Has or Has Not Been Employed

We examined observational research because it plays an important role in characterizing individual, relational, social, economic, and structural factors associated with HIV risk in SIW that should inform intervention development, by theorizing and conceptualizing context-specific causal pathways that potentially can be interrupted.10 But our review revealed few observational studies that explicitly employed a theoretical framework: only 10 of the 43 articles reviewed, or 23.6% (see Table 1). Six of this these 10 studies occurred in the U.S. with various vulnerable populations (exotic dancers;11 Hispanic women;12 women with a history of childhood neglect/abuse;13 and substance using women in14 and out of treatment settings15, 16). Half11, 12, 17–19 of the studies examined the dynamics of gender, substance use, and HIV risk, while the other half13–16, 20 only looked at individual and relational HIV risk without focusing on substance use and/or gendered dynamics.

Of the 26 unique HIV prevention interventions with SIW identified in our review, 16 reported using a theoretical or conceptual model to guide their work (see Table 2). Eleven of these interventions occurred in the U.S. with sub-populations of women affected by substance use (racial/ethnic minority,21, 22 incarcerated,23, 24 and homeless25 women), engaged in active substance use,26–32 or living with HIV.33 The others targeted substance-using female sex workers in Mexico34, 35 and South Africa,36 high-risk heterosexual women in the U.S. Virgin Islands37 and Puerto Rico,38 and pregnant IDU accessing methadone in Australia.39

All of these interventions applied theoretical or conceptual approaches targeting individual-level risk factors. Five interventions targeted substance use and/or gender-related power dynamics to some degree29, 36, 37, 40, 41 while 3 interventions used theory to articulate these dynamics at the broader social, economic, and structural-level of HIV risk.23, 25, 27

The most common theories employed in both observational and intervention studies were variants of social-cognitive theories, which have dominated the HIV prevention field since the beginning of the epidemic. These include: The Health Belief Model42 (HBM, k = 613, 15, 24, 30, 32, 37), Social Cognitive Theory43 (SCT, k = 1313, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 36–38, 40, 41), Social Learning Theory44 (SLT, k = 230, 32), Theory of Reasoned Action45 (TRA, k = 613, 16, 29, 30, 38, 40), Theory of Planned Behavior46 (TPB, k = 313, 16, 29), and the Transtheoretical Model47 (TTM, k = 229, 39). In the observational studies, such theories were used to identify individual-level mechanisms of HIV sexual risk (e.g., drug-using African American women's perceived risk for HIV risk,15 female IDU's intentions and perceived behavioral control towards using male condoms,16 and the association between a history of childhood neglect and more negative attitudes towards condoms13).

This was also true of intervention studies, which used social cognitive approaches primarily to target health beliefs (e.g. increase perceived vulnerability to HIV for drug using African American women30), building favorable social norms (e.g., identifying drug-free persons who can provide social support to enable drug-abusing women to enact safer sex behaviors when released from jail24), and increasing self-efficacy (e.g., problem-solving skills to address relapse, injection, and unsafe sex risk behaviors for pregnant women on methadone39; and assertiveness training to facilitate asking partners to use condoms for Black and Hispanic women accessing methadone22). Most studies provided limited insights about how the social-cognitive approaches were actually used to target individual-level HIV risk behaviors.21, 26, 29, 32, 38

A few studies went beyond this common set of psychosocial factors operating at the individual level to further articulate how substance use/abuse and gendered power dynamics operate at the social-structural level to confer HIV vulnerability among SIW. Half (k = 5) of the theory-informed observational studies we reviewed employed social and structural theories a-priori to guide their analysis and interpretation of results.11, 12, 17–19 For example, a qualitative study of Hispanic women in the U.S.12 used Syndemics48 theory to identify ways that social and cultural constructions of gender facilitate gender-based violence--specifically, how interpersonal violence (IPV) was the most salient social factor driving the women's risk for HIV in the context of machismo, as it constrained their latitude to negotiate reductions in a male partner's drinking or increases in condom use. A cross-sectional study with South African women attending informal drinking establishments also used Syndemics theory to show the additive effects of limited access to resources (food insecurity), gender-based violence, problem drinking, and related psychological distress on HIV-related sexual risk behaviors.18

Two qualitative analyses using the HIV Risk Environment49 framework with North American women engaged in street19 and venue-based (exotic dance clubs)11 sex exchange highlighted the ways in which social and physical environments affected the interplay of substance use, sexual activity, and HIV risk. These environments include: 1) interpersonal dynamics with boyfriends/pimps or bartenders/managers that dictated the need for women to generate income through sex work and that controlled their access to condoms and drugs, and 2) the remote nature of available space that compromised women's personal safety and ability to negotiate condom use during sex-exchanging encounters. Within these environments, the role of substance use, and in particular the need to mitigate withdrawal, was noted as driving women's need to engage in sex work, and simultaneously limiting their capacity to control their situations with male clients or partners.

Other studies explicated the intersection of violence with gendered and substance use-based HIV risk among women engaged in sex work in Russia and Canada.17, 19 This included everyday50 or symbolic51 violence experienced by SIW in their encounters with male clients, partners, and the police. Structural violence52 was articulated as a product of political criminalization of drug use and sex work that systematically drive disparities in economic and individual autonomy among SIW; limiting their access to HIV prevention, harm reduction, and health care services.

Eight of the 16 intervention studies we reviewed provided varying degrees of information on how theory-informed intervention content was developed to respond to substance use and/or gender-relevant individual,40 relational,36 social,23, 25, 29, 37, 41 economic,27 and structural23, 25 risk among SIW. For example, 4 studies29, 36, 37, 41 used the theory of Gender and Power53, 54 and Empowerment frameworks55–57 to target relational and social level risk factors influenced by gender dynamics believed to limit women's access to social support and, thereby, create greater economic dependency and risk of violence.

Mujer Mas Segura40, an intervention study in Mexico, specifically targeted individual-level risk by articulating core elements of SCT and TRA (self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, peer norms) to be responsive to the ways substance use and gender-relevant power dynamics intersect for female sex workers who inject drugs. This intervention involved increasing safer sex and safer injection negotiation skills in the contexts of women's own drug use, and teaching harm reduction strategies to reduce injection risk when injecting with a male client or male partner (e.g., waiting until after sex to inject), self-efficacy for obtaining syringes and works for personal use only when injecting with female friends, or using bleach to clean injection equipment for situations where sharing cannot be avoided (e.g., during periods of incarceration).

Another intervention, Project Power,23 used a Syndemics approach to target psychological (self-esteem), relational (gender and power inequities in relationships), and social/contextual factors (histories of trauma and abuse, substance use, and mental health problems) that reinforce each other and foster situations that lead to risk behaviors which are likely to be encountered by SIW post-incarceration. The JEWEL Project,27 combined an economic enhancement framework with SCT to support access to sustainable sources of income for drug using female sex workers in an effort to mitigate HIV risks by reducing their substance use and/or sex-related economic dependencies. Ladies Night,25 a weekly drop-in program for homeless/marginally housed cis and transgender women (most of whom use drugs) in San Francisco utilized Social Network Theory,58 feminist ethnographic methods, and a harm reduction approach in its program evaluation to describe how a gendered (woman)-sensitive social- and structural HIV prevention environment was created. This program sought to support intersecting gender and substance use-related HIV prevention needs in this population by providing clean needles, methadone referrals, safer sex resources, and HIV testing in a safe space independent of male-power dynamics known to restrict women's access to such resources.

Discussion and Conclusion

In sum, our review of published studies focused on HIV prevention among SIW revealed a general lack of relevant theoretical and conceptual foundation that articulates and then targets the interaction of individual and social-environmental factors that potentiate HIV risk and acquisition among this population across geographic contexts. Most striking was the dearth of conceptual thinking about gender itself, i.e., beyond broad statements that gender inequality and gendered power imbalances exist. With few exceptions, the studies we reviewed did not examine what it is about being female in a particular social and cultural context that informs both substance use and HIV risk and vulnerability and the interactions among them. At the same time, as most of the studies make clear, SIW are not just women, or just drug users. Rather, they are individuals with multiple, interacting social identities and characteristics related not only to their gender, but also to such things as their age, class, race/ethnicity, nationality, substance use, mental health challenges, and sex work/exchange. Moreover, as the studies note, risk or vulnerability to HIV infection is not just a property of an individual woman, but rather resides in her interactions with others in particular environments. As such, we would have expected more attention to incorporating social, as well as psychological theory than we found.

For example, one theoretical approach that we believe has particular relevance to developing a greater understanding of the lives and situations of SIW relevant to HIV prevention, but that is notably lacking in the literature, is Intersectionality. This is an area of research derived from the theory that social identities and social positions (and their inequalities) based on race/ethnicity, class, sex/gender, and other identities, such as mental health, substance use, disability status, etc. are interactive, interdependent, and mutually constitutive;59, 60 and, moreover, that these identities are not additive, but are multiplicative and potentially amplifying.61, 62 Intersectionality theory and methodology highlight the interaction of social identities and characteristics operating within varying social contexts and at multiple levels (individual, relational, institutional) and within systems of inequality, marginalization, and oppression that ultimately play out in individual-level behaviors and practices. It is a theoretical approach of significant currency in gender and feminist scholarship that is well-suited to SIW in the context of HIV/AIDS,63 but has not been widely applied.

Intersectionality is akin to Syndemics, which similarly refers to a theoretical understanding of multiple, co-occurring phenomena, with an emphasis on overlapping health and social problems (rather than identities) that are simultaneously experienced by a population.48, 64 As we have seen in this review, syndemic approaches have been only nominally applied to women in the context of HIV/AIDS, with seminal work examining the overlap between substance abuse, violence, and AIDS (aka “SAVA”).48, 65 The paper by Gilbert et al.7 in this volume makes an important contribution to advancing a Syndemics framework for SIW.

In the context of HIV, what both of these theoretical perspectives contribute is a recognition that individuals cannot be reduced to single, mutually exclusive, epidemiologically-defined characteristic, (e.g., a mode of transmission category, such as injecting drug use), and considered out of the context of their environments, relationships and social (including cultural, political, and economic) position.66, 67 These perspectives also underscore that HIV risk resides not just at the individual, behavioral level, but also at the relational68 and environmental (including neighborhood) levels.63 We believe that research related to SIW would benefit from greater theoretical and conceptual thinking that links insights from intersectionality,63 syndemics,64 risk environment,49, 69 and social ecological models.70 This includes both observational research to better identify and characterize relevant mechanisms by which gender dynamics and substance use potentiate the likelihood of HIV transmission and acquisition among SIW and shape the social and environmental contexts in which their HIV risk occurs, and intervention research derived from such formative work. This work—charting a plausible pathway and determining were and how best to disrupt it—is essential to reach our collective goal of developing and implementing programs, services, and policies that are appropriate and meaningful to SIW and that will effectively mitigate their HIV risk in all settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: LRS was supported by NIH training grant T32 DA023356.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, et al. Substance use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: Risk environments and implicaitons for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624. This issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) [Accessed 15 January, 2015];Women who Inject Drugs and HIV: Addressing specific needs. Policy Brief. 2014 Available at: http://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/publications/WOMEN_POLICY_BRIEF2014.pdf.

- 3.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [Accessed 23 January 2015];Annual Report. 2006 Available at: Available at: http://harm-reduction.org/sites/default/files/pdf/Download%20%5BEnglish%5D_23.pdf.

- 4.El-Bassel N, Terlikbaeva A, Pinkham S. HIV and women who use drugs: double neglect, double risk. The Lancet. 2010;376:312–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kippax S. Effective HIV prevention: the indispensable role of social science. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17357. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wechsberg WM, Deren S, Myers B, et al. Gender-specific HIV prevention interventions for women who use alcohol and other drugs: The evolution of the science and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000627. This issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, et al. Targeting SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence and AIDS) Syndemic among Women and Girls: A Global Review of Epidemiology and Integrated Interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626. This issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG, et al. Structual interventions for HIV preventiona mong women who use or inject drugs: A Global perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000638. This issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20. 7015-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Global Public Health. 2011;6:S293–309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman SG, Lilleston P, Reuben J. More than a dance: the production of sexual health risk in the exotic dance clubs in Baltimore, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:475–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, et al. Hispanic women's experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22:46–54. doi: 10.1177/1043659610387079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein H, Elifson KW, Sterk CE. Childhood neglect and adulthood involvement in HIV-related risk behaviors. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu E, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, et al. Dyadic HIV status and psychological distress among women on methadone. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown EJ, M Risk behavior, perceptions of HIV risk, and risk-reduction behavior among a small group of rural African American women who use drugs. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook DW, Brook JS, Whiteman M, et al. Psychosocial risk and protective factors for condom use among female injection drug users. The American Journal on Addictions. 1998;7:115–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King EJ, Maman S. Structural barriers to receiving health care services for female sex workers in Russia. Qual Health Res. 2013;23:1079–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732313494854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, et al. Co-occurring psychosocial problems and HIV risk among women attending drinking venues in a South African township: A syndemic approach. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;45:153–62. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, et al. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:911–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Li X, Zhou Y, et al. Perceived peer engagement in HIV-related sexual risk behaviors and self-reported risk-taking among female sex workers in Guangxi, China. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1114–21. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.750709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peragallo N, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, McCabe BE, et al. The efficacy of an HIV risk reduction intervention for Hispanic women. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1316–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schilling RF, el-Bassel N, Schinke SP, et al. Building skills of recovering women drug users to reduce heterosexual AIDS transmission. Public Health Rep. 1991;106:297–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fasula AM, Fogel CI, Gelaude D, et al. Project POWER: Adapting an evidence-based HIV/STI prevention intervention for incarcerated women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2013;25:203–15. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.el-Bassel N, Ivanoff A, Schilling RF, et al. Preventing HIV/AIDS in drug-abusing incarcerated women through skills building and social support enhancement: preliminary outcomes. Soc Work Res. 1995;19:131–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magee C, Huriaux E. Ladies' night: Evaluating a drop-in programme for homeless and marginally housed women in San Francisco's mission district. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koblin BA, Bonner S, Hoover DR, et al. A randomized trial of enhanced HIV risk-reduction and vaccine trial education interventions among HIV-negative, high-risk women who use noninjection drugs: the UNITY study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:378–87. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b7222e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman S, German D, Cheng Y, et al. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW. Who's getting the message? Intervention response rates among women who inject drugs and/or smoke crack cocaine. Prev Med. 2003;37:119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW, et al. HIV risk reduction among African-American women who inject drugs: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:73–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1022565524508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy HV, McCoy CB, Lai S. Effectiveness of HIV interventions among women drug users. Women Health. 1998;27:49–66. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens SJ, Estrada AL, Estrada BD. HIV sex and drug risk behavior and behavior change in a national sample of injection drug and crack cocaine using women. Women Health. 1998;27:25–48. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coyle SL. Women's drug use and HIV risk: findings from NIDA's cooperative agreement for community-based outreach/intervention research program. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seth P, Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ. Exposure to alcohol problems and its association with sexual behaviour and biologically confirmed Trichomonas vaginalis among women living with HIV. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:390–2. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stockman JK, Morris MD, Martinez G, et al. Prevalence and correlates of female condom use and interest among injection drug-using female sex workers in two Mexico–US border cities. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1877–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaines TL, Rudolph AE, Brouwer KC, et al. The longitudinal association of venue stability with consistent condom use among female sex workers in two Mexico-USA border cities. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:523–9. doi: 10.1177/0956462412473890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Lam WK, et al. Substance use, sexual risk, and violence: HIV prevention intervention with sex workers in Pretoria. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:131–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. Developing an HIV intervention for indigent women substance abusers in the United States Virgin Islands. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:iv74–83. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres R, Hilerio CM, Silva G, et al. Concerns about HIV and sexually transmitted infection among low-risk and high-risk women, Puerto Rico. Ethn Dis. 2008;18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Neill K, Baker A, Cooke M, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive behavioural intervention for pregnant injecting drug users at risk of HIV infection. Addiction. 1996;91:1115–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91811154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vera A, Abramovitz D, Lozada R, et al. Mujer Mas Segura (Safer Women): a combination prevention intervention to reduce sexual and injection risks among female sex workers who inject drugs. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:653. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-653. 2458-12-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW Program. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Defic Syndromes. 2004;37:S58–67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Anonymous Preventing AIDS. Springer; 1994. The health belief model and HIV risk behavior change; pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE. Using the Theory of Reasoned Action as a Framework for Understanding and Changing AIDS-Related Behaviors. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1989. pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Toward a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviors: Processes of Change. Applied Clinical Psychology. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer M. AIDS and the health crisis of the US urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:931–48. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, et al. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1026–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheper-Hughes N. Small wars and invisible genocides. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourdieu P. Masculine Domination. Stanford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farmer P. On suffering and structural violence: a view from below. Daedalus. 1996:261–83. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connell RW. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wingood GM, Scd, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:539–65. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rappaport J. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Am J Community Psychol. 1987;15:121–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00919275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levine OH, Britton PJ, James TC, et al. The empowerment of women: A key to HIV prevention. J Community Psychol. 1993;21:320–34. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wechsberg W. Facilitating empowerment for women substance abusers at risk for HIV. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;61:158. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kadushin C. Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. U.Chi.Legal F. 1989:139. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doyal L. Challenges in researching life with HIV/AIDS: an intersectional analysis of black African migrants in London. Culture, health & sexuality. 2009;11:173–88. doi: 10.1080/13691050802560336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bowleg L. When Black lesbian woman≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex roles. 2008;59:312–25. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watkins-Hayes C. Intersectionality as Theory, Method, and Praxis in the Sociology of HIV/AIDS. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014;40:431–57. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:423–41. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. Journal of Women's Health. 2011;20:991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hankivsky O. Women's health, men's health, and gender and health: implications of intersectionality. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1712–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dworkin SL. Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7:615–23. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:963–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2010;376:268–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, et al. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482. 2458-13-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.