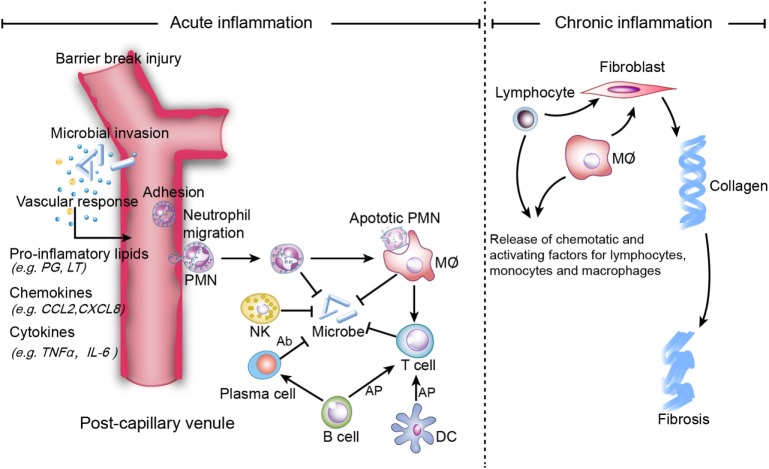

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of acute and chronic inflammation. Within a few hours of stimulation (injury, trauma, stress, or infection), the release of pro-inflammatory lipids (e.g., prostaglandin (PG), leukotriene (LT), involved in vasodilation), chemokines (e.g., C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), C-X-C motif ligand 8 (CXCL8), involved in chemotaxis and adhesion), and cytokines [e.g., Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6] elicits the recruitment of neutrophils. Other immune cells [i.e., natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), B cells, and T cells] also participate in the process. NK cells kill microbes via complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Macrophages directly phagocytize organisms and apoptotic neutrophils, while B cells are converted to plasma cells to kill organisms via secreted antibodies, which are referred to as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Macrophages, B cells and DCs activate T cells via antigen cross presentation (AP). Homeostasis will be restored if inflammation is resolved completely, while non-resolution leads to chronic inflammation, which is characterized by persistent tissue infiltration by immune cells (e.g., macrophages, lymphocytes). In the extracellular zone, lymphocytes and macrophages release factors that result in the deposition of extracellular collagen and an excessive inflammatory response.