Abstract

Purpose

To digitally stain spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) images of the optic nerve head (ONH), and highlight either connective or neural tissues.

Methods

OCT volumes of the ONH were acquired from one eye of 10 healthy subjects. We processed all volumes with adaptive compensation to remove shadows and enhance deep tissue visibility. For each ONH, we identified the four most dissimilar pixel-intensity histograms, each of which was assumed to represent a tissue group. These four histograms formed a vector basis on which we ‘projected' each OCT volume in order to generate four digitally stained volumes P1 to P4. Digital staining was also verified using a digital phantom, and compared with k-means clustering for three and four clusters.

Results

Digital staining was able to isolate three regions of interest from the proposed phantom. For the ONH, the digitally stained images P1 highlighted mostly connective tissues, as demonstrated through an excellent contrast increase across the anterior lamina cribrosa boundary (3.6 ± 0.6 times). P2 highlighted the nerve fiber layer and the prelamina, P3 the remaining layers of the retina, and P4 the image background. Further, digital staining was able to separate ONH tissue layers that were not well separated by k-means clustering.

Conclusion

We have described an algorithm that can digitally stain connective and neural tissues in OCT images of the ONH.

Translational Relevance

Because connective and neural tissues are considerably altered in glaucoma, digital staining of the ONH tissues may be of interest in the clinical management of this pathology.

Keywords: glaucoma, optic nerve head, optical coherence tomography, adaptive compensation, digital staining

Introduction

Structural parameters of the optic nerve head (ONH) measured with optical coherence tomography (OCT), such as the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer1 and the minimum rim width2,3 have been recently considered for improving glaucoma diagnosis.4 It is believed that if other structural parameters linked to ONH connective tissues could be extracted in vivo, it could further increase the value of OCT in glaucoma clinics.5,6 This is because ONH connective tissues, such as the peripapillary sclera. Bruch's membrane, and the lamina cribrosa (LC) have been identified as key players in this pathology.7–14

Unfortunately, OCT image quality is still greatly hampered by the presence of artifacts and by poor tissue visibility in the deepest layers.15 This is due to signal attenuation, whereby signal strength diminishes as a function of tissue depth. This phenomenon is a clinical barrier to glaucoma applications due to the poor visibility of deep ONH connective tissues with commercial OCT devices.

To correct for signal attenuation and improve connective tissue visibility, we have recently proposed several compensation technologies.15–17 These post-processing techniques have allowed for significant improvements in the visibility of ONH tissues, such as enhanced choroid/scleral interface, anterior/posterior LC surface, and LC insertion sites.18 While their uses have considerably facilitated the manual delineation of ONH connective tissues, automated detection/segmentation has remained a challenge.

In this study, we propose a novel algorithm that, when combined with adaptive compensation, can digitally ‘stain' ONH tissues from OCT images. While several studies have tried to provide segmentation or classification methods for ocular OCT,19–33 our aim was primarily to highlight tissue groups (including connective and neural tissues) and enhance their visibility. Although the proposed approach does not identify tissue boundaries or classes, it can facilitate visual image analysis and offers great prior knowledge for subsequent segmentation or classification. This digital staining algorithm may be widely applicable to other ocular tissues such as the trabecular meshwork, Schlemm's canal, and corneal scars.

Materials and Methods

OCT Image Acquisition

Spectral-domain OCT volume scans were acquired from one eye of 10 healthy subjects using a commercially available device (Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Inclusion criteria for these subjects were: intraocular pressure (IOP) less than or equal to 21 mm Hg, healthy ONHs with vertical cup disc ratio less than or equal to 0.5, and normal visual fields. Imaging was performed at the Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore, where the Institution's ethics committee approval was obtained; all subjects gave written informed consent and were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each volume scan comprised of 97 horizontal B-scans acquired over a 15° × 15° retinal window. There were 384 A-scans (of 496 pixels each) per B-scan; each B-scan was averaged 20 times for speckle noise reduction, and acquired in enhanced-depth imaging mode.

Adaptive Compensation – Shadow Removal and Contrast Enhancement

In order to remove light-attenuation artifacts, all OCT volumes were processed (post acquisition) using adaptive compensation (AC).15,16 When applied to OCT images of the ONH, AC has been demonstrated to remove blood vessel shadows (cast by the central retinal vessel trunk), to improve the visibility of the anterior/posterior LC boundaries, to improve the visibility of the LC insertions into the sclera, and to significantly increase the visibility of the choroid and peripapillary sclera.18,35 An energy threshold exponent of six (to limit speckle noise over-amplification), and a contrast exponent of two (to enhance ONH tissue contrast) were both used for each compensated volume.

OCT Digital Staining – Description of the Algorithm

In this study, we developed a digital staining algorithm that can classify (or isolate) different tissue groups of the ONH. Our main assumption is that the pattern distribution of reflectivity of the ONH tissues (as measured by OCT and corrected with adaptive compensation) varies according to tissue composition/type. For each OCT volume of the ONH, we aimed to extract N pixel-intensity histograms to represent the N different tissues (or tissue groups) of the ONH. These N histograms can then be used to digitally stain the OCT volumes.

The principle of OCT digital staining is as follows: for each OCT volume of the ONH, we first manually selected a region of interest (ROI) within the LC. The selected ROI was assumed to exhibit pixel intensity values representative of ONH connective tissues. The ROI pixel intensities were then represented as a histogram-vector h1 (vector size: 256 × 1), in which each vector component was the number of ROI voxels for a given gray scale value (from 1–256).

For our next step, we aimed to identify the histogram-vector h2 that was the most dissimilar to h1. We assumed that if h2 was highly dissimilar to h1, it would be representative of an ONH tissue (or tissue group) different from connective tissues. For simplicity, we assumed that h2 was most dissimilar to h1 when a function of the scalar product h1 × h2 was minimum. Note that this process is similar to minimizing a cross-correlation coefficient applied to histogram-vectors.36 To this end, we first divided each OCT volume into multiple partially overlapping (8 × 8 × 5 voxels) ROIs (33 × 33 × 5 voxels). For each ROI (now represented as a histogram-vector h2), we computed the scalar product h1 × h2. We then identified the ROI (and corresponding h2) that provided the smallest scalar product value.

Once the first two most dissimilar histogram-vectors (representing tissues) were found the technique could be iterated. For instance, a histogram-vector hn can be obtained when the function of its scalar products with the n − 1 previous histogram-vectors is minimum. Using the proposed approach, we aimed to identify a basis of four histogram-vectors (assumed to be representative of four tissues or tissue groups, including background noise) for each OCT volume of the ONH.

For a given OCT volume, the four histogram-vectors can now be used to generate four digitally stained volumes representative of four different tissue types. To this end, each OCT volume was divided into multiple overlapping ROIs (9 × 9 × 1 voxels). The digitally stained image P1 was obtained by projecting all histogram-vectors (representative of all ROIs; the histograms are normalized and sorted in the base according to maximum position, and extrema histograms are maximized below and above their maximum values positions, respectively) on h1. In other words, the voxel intensity of P1 with voxel coordinates (i, j, k) was the scalar product of h1 with the histogram-vector representing an ROI centered on (i, j, k). The digitally stained images P2, P3, and P4 were obtained by performing similar projections with h2, h3, and h4, respectively.

The digital staining algorithm was implemented in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA).

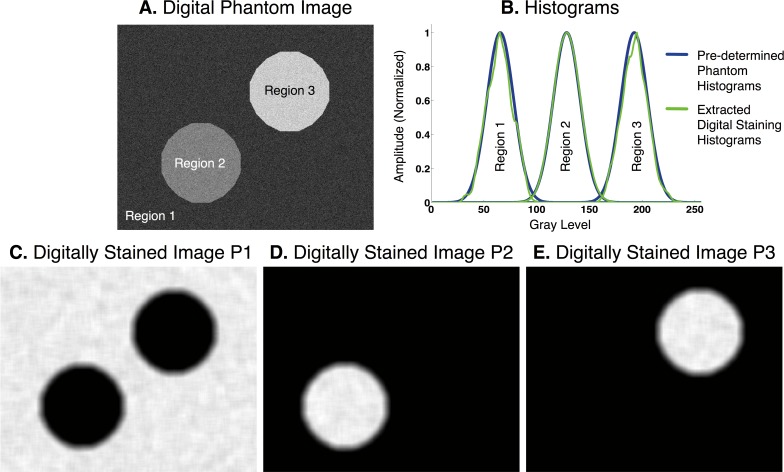

OCT Digital Staining –Verification of the Algorithm

In order to test the performance and verify the accuracy of our digital staining algorithm, we generated a two-dimensional (2D) digital phantom image (8 bits) that contained three texture patterns (regions 1–3 in Fig. 1A), each of which followed a randomly chosen Gaussian distribution. The histogram-vector h1 was manually selected from region 1 (ROI size: 17 × 17 pixels). The digital phantom was then processed with 17 × 17 pixels search ROIs in order to identify a basis of three histogram-vectors h1, h2, and h3 (vector size: 256 × 1, corresponding to the 256 image gray levels). Histogram-vectors (representative of 17 × 17 pixels ROIs in the digital phantom image) were then projected on each histogram vector basis to generate three digitally stained images: P1, P2, and P3. To assess the performance of digital staining, we: (1) computed contrasts across regions (region 1 versus region 2 and region 1 versus region 3, in the baseline and digitally stained images), and (2) compared the three extracted histogram-vectors to those used to generate the digital phantom image.

Figure 1.

(A) A digital phantom was generated with three regions, each of which had pixel intensities that followed a randomly generated Gaussian distribution. (B) Predetermined histogram-vectors of the digital phantom for the three regions are compared with those extracted with digital staining. A good agreement was obtained. (C–E) Digitally stained images P1, P2, and P3 that highlight regions 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Digital Stain Contrasts for ONH Images

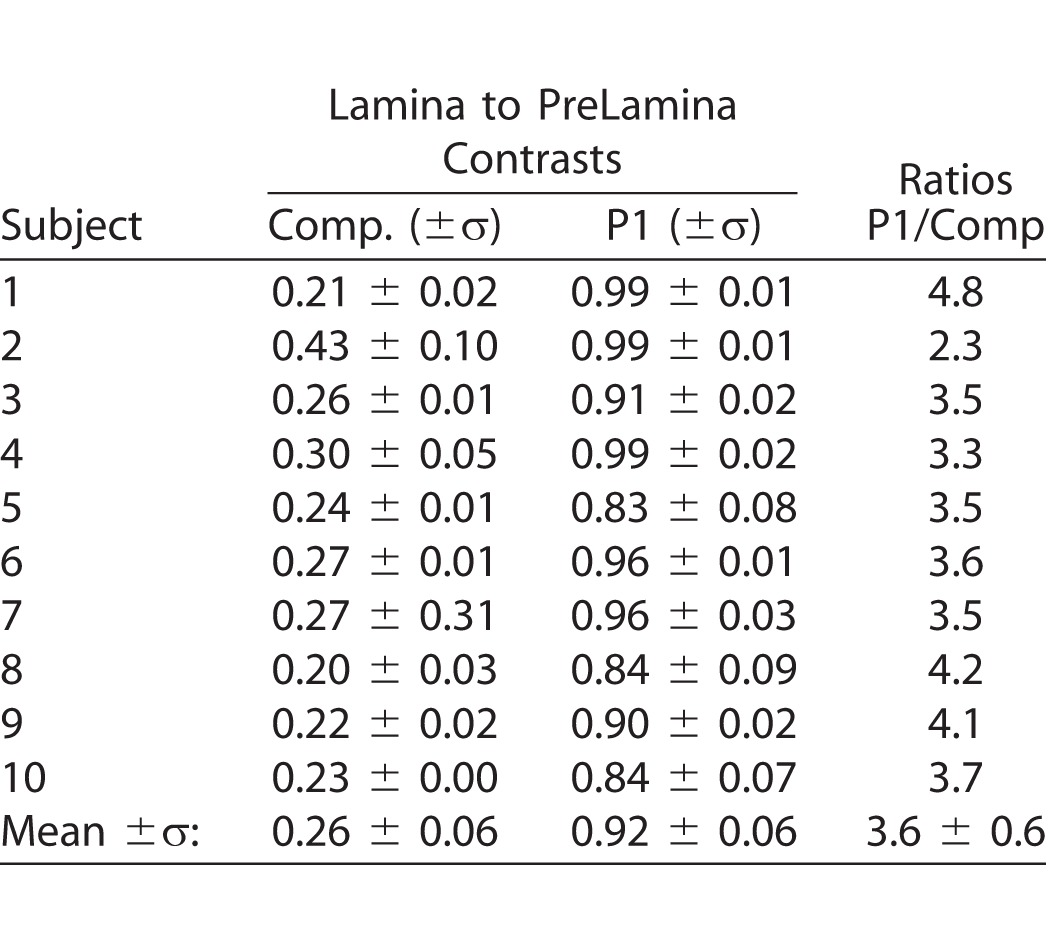

To verify that our algorithm can isolate different tissues of the ONH, we computed the digital stain contrast between the LC and the prelamina for the compensated and digitally stained images. The digital stain contrast is an indicator of whether a given tissue has been isolated from other tissues that are different in nature (e.g., connective versus neural tissue). The digital stain contrast was calculated across the anterior LC boundary because it separates connective from neural tissues. The digital stain contrast was defined as |(I1– I2) / (I1+ I2)|, where I1 was the mean image intensity of a ROI (30 × 30 pixels) located within an arbitrarily selected region of the LC, and I2 was that within the prelamina. The contrast was estimated for three different slices in each transformed dataset. By definition, the digital stain contrast varies between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a high digital stain contrast (i.e., high LC visibility).

Comparison with K-Means Clustering

Although the proposed method is not a clustering/classification one (the images are not transformed into clusters/classes, but in intensity images), as no algorithm equivalent to the proposed one is readily available, a k-means clustering algorithm (function kmeans_fast_color; Matlab) was also applied to the compensated images to compare the ability of digital staining to isolate tissue textures with that of a common clustering method. Specifically, k-means clustering was used to isolate three and four clusters, and compared qualitatively with digital staining.

Statistical Analysis

Digital stain contrasts were reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses to compare digital stain contrasts were performed by using paired Student's t-test in Matlab, with P less than 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

Digital Staining – Algorithm Verification

We found that our digital staining algorithm was able to isolate (i.e., digitally stain) the three ROIs from the proposed digital phantom. Specifically, the digitally stained image P1 (Fig. 1C) was able to isolate the background (region 1), the image P2 (Fig. 1D) the lower left circle (region 2), and the image P3 (Fig. 1E) the upper right circle (region 3). We also found that contrasts across region boundaries (region 1 versus region 2 and region 1 versus region 3) were excellent in all digitally stained images and were always higher than 0.97 (considerably higher than those in the baseline image; e.g., region 1 versus region 2, baseline contrast: 0.31; region 1 versus region 3: 0.58). Finally, the histogram vectors that were extracted with digital staining matched relatively well those that were used to generate the digital phantom (Fig. 1B).

Digital Staining of ONH Tissues

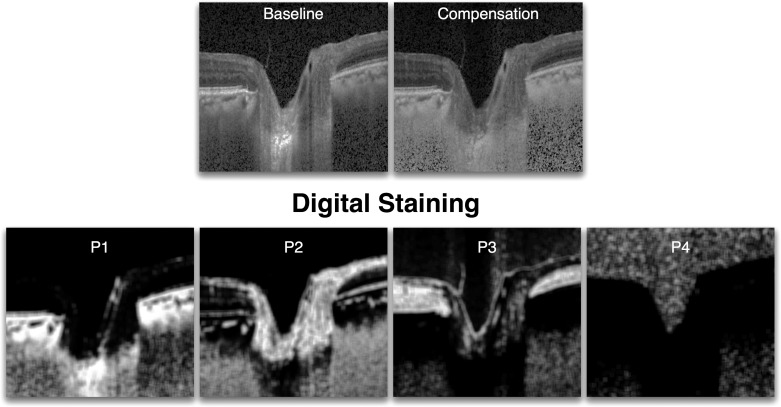

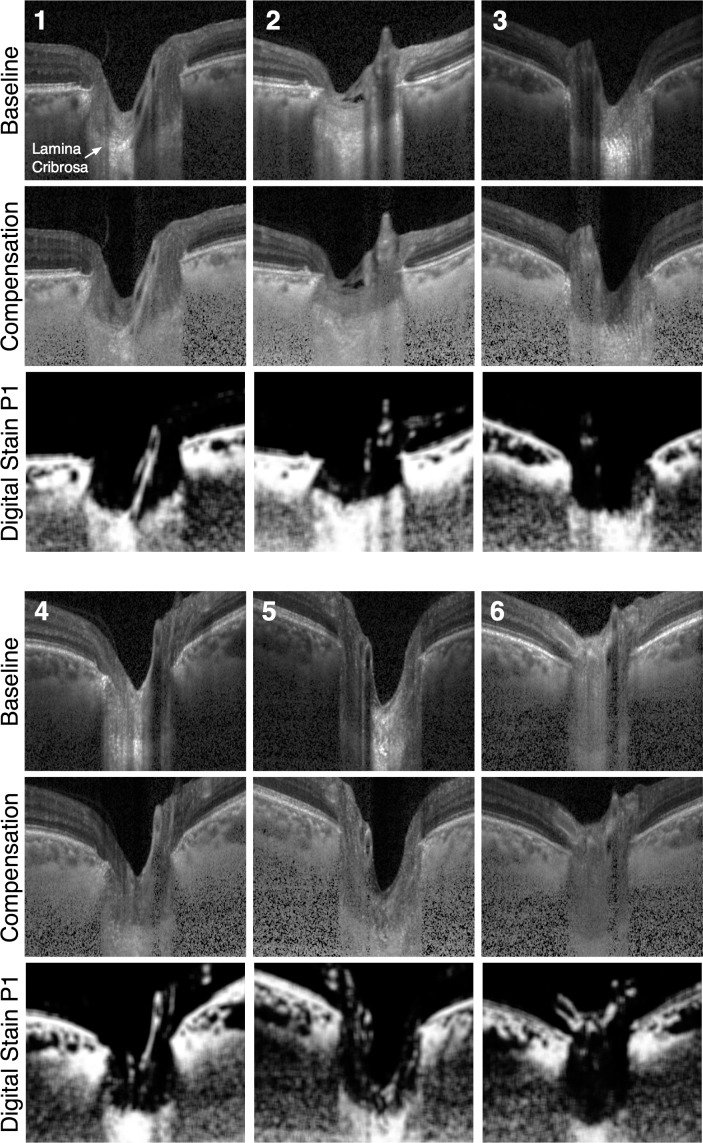

Baseline, compensated, and digital stain images (projections P1–P4) for a healthy ONH (subject #1) can be found in Figure 2. We found that the digitally stained image P1 was able to highlight predominantly connective tissue structures including the peripapillary sclera, the LC, Bruch's membrane, the choroid, and the central retinal trunk vessel walls. This was true even in regions exhibiting high shadowing artifacts (e.g., nasal side of the optic disc). In the image P1, LC visibility was considerably enhanced, which was highly consistent across all 10 subjects (6 of 10 subjects are represented in Fig. 3). This was confirmed through calculations of the digital stain contrast between the LC and the prelamina. On average, our digital staining algorithm significantly increased the digital stain contrast of the LC from 0.26 ± 0.06 (compensated) to 0.91 ± 0.07 (P < 0.001; Table 1), indicating a drastic increase in anterior LC visibility (×3.6 ± 0.6 improvement). In the image P1, we also found that the visibility of the choroidal vessels was excellent.

Figure 2.

Baseline, compensated, and digitally stained images (projections P1–P4) for a healthy ONH (subject #1). P1 mostly captured connective tissue structures, P2 isolated the nerve fiber layer and the prelaminar tissue, P3 highlighted the other retinal cell layers, P4 identified the background noise and provided a ‘mask' of the ONH tissues.

Figure 3.

Baseline, compensated, and digitally stained images (projections P1) for 6 (of 10) healthy ONHs. P1 consistently stained for connective tissues (mostly sclera, choroid, and lamina cribrosa). In the P1 images, the lamina cribrosa was even stained in the nasal region even though strong blood vessel shadowing was observed in the baseline images.

Table 1.

Digital Stain Contrasts Computed across the Anterior LC Surface (Using 3 B-Scans Per Subject) for all 10 Subjects

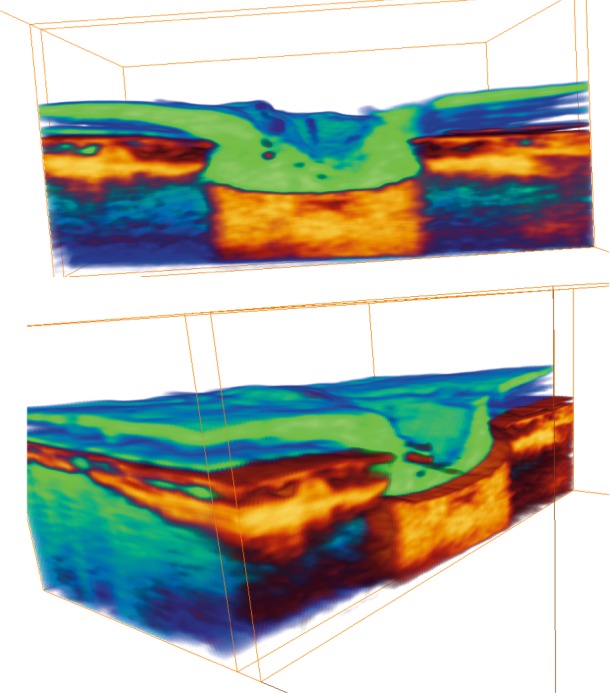

We also found that the digitally stained image P2 was able to highlight the nerve fiber layer and the prelamina (Fig. 2), and in the digitally stained image P3, the remaining layers of the retina. The digitally stained image P4 was not representative of an ONH tissue or tissue group, but instead highlighted the image background (everything but ONH tissues). A three-dimensional (3D) volume rendering of the digitally stained volumes P1 and P2 can be visualized in Figure 4 (subject #1) in order to illustrate the high degree of separation that can be obtained between connective and neural tissues.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional volume rendering of the digitally stained volumes P1 (red/orange) and P2 (green/blue) for subject #1. A high degree of separation can be observed between connective (P1) and nervous tissues (P2).

Comparison with K-Means Clustering

Examples of k-means clustering for three and four clusters are displayed in Figure 5 (subject #1) together with the digital staining outputs for the same subject.

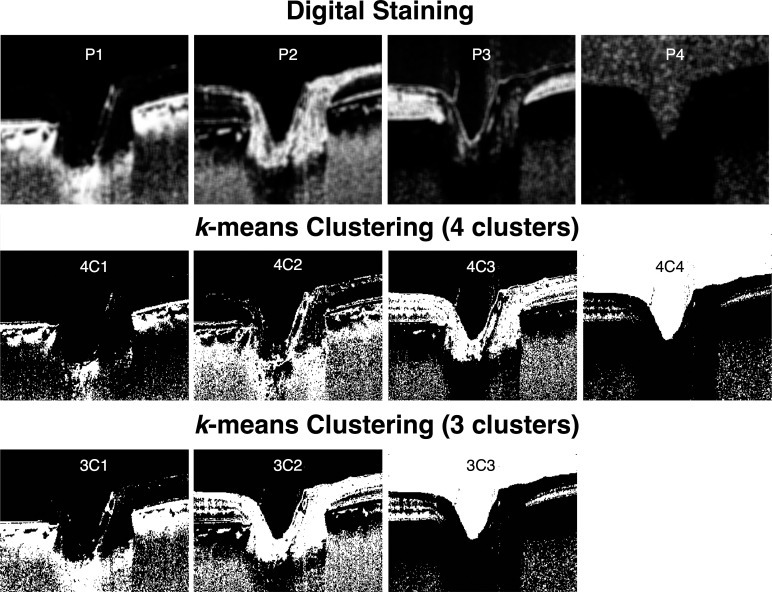

Figure 5.

Comparison of digital staining with k-means clustering with four and three clusters. Digital staining is able to separate ONH tissue layers (e.g., prelamina, nerve fiber layer, noise) that are not well separated by k-means clustering.

Using four clusters, k-means clustering was able to isolate neural tissues (prelamina + retina in 4C3) but performed poorly to isolate connective tissues (sclera and LC in 4C1 and 4C2 versus P1). Furthermore k-means clustering could not isolate the nerve fiber layer (4C3 versus P2). The noise image (4C4) also included retinal layers, which was not the case with digital staining (P4).

Using three clusters, k-means clustering performed well in identifying connective tissues (sclera + LC in 3C1), but did not perform as well as digital staining in identifying neural tissues (3C2 versus P2 and P3). In addition, the noise image (3C3) included retinal layers, which was not the case with digital staining (P4).

Discussion

In this study, we have developed and tested a digital staining algorithm for OCT images of the ONH. Our algorithm was verified with a digital phantom and tested with OCT data from 10 healthy subjects. For OCT images of the ONH, we found that our algorithm was able to isolate connective tissues, prelaminar tissues and the nerve fiber layer, other retinal layers, and the OCT background, as four separate digitally stained volumes. Our method is as attractive as it is simple and could have applications for the clinical management of glaucoma using OCT. To the best of our knowledge, no digital staining techniques have yet been proposed for OCT images of the eye.

In this work, we found that connective tissues of the ONH (including the peripapillary sclera. the LC, the choroid, Bruch's membrane, and the central retinal vessels) were highly visible in the digitally stained images P1. This was confirmed quantitatively by a marked increase in digital stain contrast across the anterior LC boundary. The results were also highly consistent for all 10 subjects. An improved visibility of connective tissues of the ONH has important clinical implication for glaucoma. Connective tissues are the main load bearing elements of the ONH, and there is evidence to suggest that biomechanical and/or morphologic features of these tissues may serve as strong biomarkers for glaucoma. For instance, we recently reported that LC shape was associated with several risk factors for glaucoma,36 and that LC strain relief following trabeculectomy was associated with visual field loss.37 Furthermore, a recent study by Yang et al.7 summarized the main connective tissue changes associated with chronic IOP elevation in a monkey model. The five connective tissue changes included: post-laminar deformation, laminar thickening, scleral canal expansion, laminar migration, and scleral bowing. It is highly plausible that some or all of these phenomena will hold true in humans (as already demonstrated for some),38,39 emphasizing the importance of monitoring connective tissue behavior in vivo. Our digital staining algorithm may help serve that purpose.

Digital staining, as proposed herein, should also considerably facilitate the automated segmentation of connective tissues. While automated segmentation of retinal cell layers in OCT images is robust,40 automated segmentation of the LC and of the choroidal vessels has remained a challenge, and only a few solutions, sometimes complex, have been proposed.41–44 While this is beyond the scope of the present work, simple segmentation algorithms should be able to be combined with digital staining to automatically identify structures such as the anterior LC surface or the choroidal vessels and this is the focus of ongoing work within our group.

In this study, we found the digitally stained images P2 represented the nerve fiber layer and the prelaminar tissue, while the digitally stained images P3 represented all other retinal layers. These tissues were identified because they were found to be the most dissimilar to connective tissues (through the minimization of scalar products between histogram vectors). We believe that digital staining opens the door to robust and automated quantification methods to assess nervous tissue damage/changes in glaucoma. For instance, automated characterization of nervous tissue parameters, such as nerve fiber layer thickness, prelaminar volume, and minimum rim width should become facilitated with digital staining.

Interestingly, the digitally stained images P4 highlighted the image background, that is, the vitreous humor above the inner limiting membrane and the OCT noise in the deepest part of the images. In other words, the images P4 provided a mask of all visible ONH tissues, P4 images could eventually be used to detect the inner limiting membrane, and/or to filter deep OCT noise, which may be useful as the first step of a segmentation algorithm.

It is worth noting that the performance of digital staining was optimum only when combined with adaptive compensation. If digital staining were to be directly applied to baseline OCT images of the ONH, typical OCT artifacts, such as blood vessel shadows and poor connective tissue visibility at high depth would still remain in the digitally stained images (data not shown). As discussed in our prior publication,16 this illustrates that adaptive compensation may be a necessary first step toward a simple solution to automatically segment the ONH tissues.

When compared with k-means clustering, it was observed that digital staining was able to extract four different layers of tissue textures, whereas k-means clustering generated mixed results. With four clusters, k-means clustering was not able to isolate the anterior LC boundary (4C1versus P1 in Fig. 5), and the nerve fiber layer (4C2 and 4C3 versus P2). In addition, 4C4 contained both nerve tissues and noise (whereas P4 only highlighted noise). With three clusters, k-means clustering was able to produce a ‘connective-tissue' image (3C1) with similarities to P1, but other features such as the nerve fiber layer and the noise could not be extracted. On the other hand, k-means clustering is relatively faster than digital staining, and it may prove useful when extracting the ‘connective-tissue' image 3C1. However, it remains important to emphasize that digital staining is able to isolate several tissue textures and does not simply separate gray levels as clusters in the compensated images.

Several limitations in our work warrant further discussion. First, we were unable to provide an additional validation of our algorithm by comparing our digitally stained images to those obtained from histology. This is, unfortunately, extremely difficult to achieve as one would need to image an ONH with OCT, process it with 3D histology, and register both volumes. Note that the broad understanding of OCT ONH anatomy to histology has been based on a single comparison with a normal monkey eye scanned in vivo at an IOP of 10 mm Hg and then perfusion fixed at time of sacrifice at the same IOP.45 The tissue typing delineated by our digital staining techniques matches the expected relationships observed in this canonical work. At the time of writing, there have been no published experiments matching human ONH histology to OCT images. While the absence of this work prevents an absolute validation of our technique, the same shortcoming necessarily applies to every other in vivo investigation of deep OCT imaging of the human investigation, many publications of which predate even the publication of the comparison with the monkey ONH.

Second, we limited our analysis to a small group (10 subjects). We did not include cases with ‘complex' ONH morphologies such as glaucoma, papilledema, peripapillary atrophy, and ONH drusen. However, it is encouraging to note that our data were highly consistent across these subjects. Current work is ongoing to further test the performance of digital staining in larger groups of subjects, with various disorders, and using additional commercially available OCT devices.

Third, digital staining was only tested for a given number of histogram vectors (here, 4) and a given set of ROI values. Note that other parameters values were explored and led to similar digital stain results (data not shown). It should be emphasized that as long as the chosen ROIs are representative but smaller than the tissues of interest that need to be detected, digital stain results will remain consistent.

Fourth, our digital staining algorithm requires an initial manual input to generate the first histogram vector h1 (representative of connective tissues). This meant that the user of the algorithm had to first identify a small ROI within the LC. We chose such an implementation because it helped considerably reduce computational time, and because in practice, the user may be interested in selecting a specific tissue that needs to be digitally stained. Future research may offer the possibility to fully automate the process if needed.

Fifth, digital staining is currently unable to differentiate the LC from the retrolaminar tissues. We believe this is because current commercial OCT technology (wavelength in the range of 800–1000 nm) fails to properly identify the posterior surface of the LC. In our previous work, we found that the posterior LC was poorly visible and only visible in 6.3% to 13.5% of patients in a population of 60 healthy and 60 glaucoma patients imaged with 3 commercial OCT devices.18 The visibility of the posterior LC boundary was only slightly improved when enhanced-depth imaging and/or adaptive compensation was combined with OCT (visible in 12.3%–21% of patients). Because digital staining is highly dependent on the original OCT signal, an improvement in OCT hardware would likely be required to differentiate the LC from the retrolaminar tissues.

Sixth, while compensation can significantly improve image quality, in some instances, it may generate its own artifacts. These artifacts will naturally remain during the digital staining step, as digital staining does not modify the images but rather highlight tissue groups. Next-generation compensation algorithms are required to further improve digital staining.

Seventh, it should be noted that the present method is not a segmentation method nor a clustering method, but indeed a texture staining approach where specific tissues are highlighted. Future work could consider using more complex texture features or seek to combine the digital staining outputs with segmentation algorithms to automatically delineate the boundaries of the different tissue types.

Eighth, digital staining when combined with swept-source OCT (instead of spectral-domain OCT) may provide improved tissue visibility. However, our previous study demonstrated that swept-source OCT (with adaptive compensation) performed as well as spectral-domain OCT (with enhanced-depth imaging and adaptive compensation) in identifying the anterior LC surface and the LC insertions into the peripapillary sclera. The visibility of the posterior LC surface remained poor with either swept-source or spectral-domain OCT.18 Further studies are required to assess the performance of digital staining when combined with swept-source OCT.

Ninth, digital staining will not be able to provide direct information about changes in neural and/or connective tissues. To assess such changes, digital staining will need to be combined with other segmentation algorithms that can quantify (e.g., thickness, volume, curvature, and morphology).

Tenth, digital staining approximately took 60 minutes to process a 3D OCT volume composed of 100 B-scans (<1 minute per slice) on a standard computer (Intel Processor i5; Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA) using Matlab. K-means clustering was faster and only took several seconds for a single B-scan. However, please note the following: (1) k-means clustering was not implemented in 3D (only 2D) and a 3D implementation is likely to be more computationally expensive, (2) digital staining was not optimized for code efficiency, (3) digital staining will run significantly faster (several orders of magnitude) in a different language such as C++, or if implemented in a Graphics Processing Unit environment.

Finally. It would have been ideal to quantitatively compare the results from digital staining with those from k-means clustering, but such a comparison would be arbitrary as the results are different in nature. Indeed, the k-means algorithm returns information about clusters (binarized information) while digital staining the ‘likeliness' (in %) of a given pixel to belong to a specific tissue or tissue group. As the cluster information is either one or zero, either a distance measure (measure of differences) would be based on arbitrary values, or the comparison of binarized images with both approaches would depend on a selected binarization threshold value (for digital staining). Furthermore, as there is currently no OCT ground truth information to assess both results independently, it is difficult to determine a quantitative level of success for each approach. One could argue that the comparison could be performed on synthetic data; however, the results would be excellent for both approaches, and a quantitative distance-based comparison would provide inconclusive results. Nevertheless, we still believe a qualitative comparison, as presented herein, is useful in assessing both approaches.

In conclusion, we have described a novel algorithm that can digitally stain connective and neural tissues in OCT images of the ONH. Our algorithm was verified with a digital phantom, compared with a modern clustering algorithm, and tested in 10 subjects with consistent digital stains. Because ONH connective and neural tissues are altered in glaucoma, digital staining (when combined with segmentation algorithms to derive measures of ONH morphology) may be of interest in the clinical management of glaucoma. Digital staining may also have wide applicability in other areas of ophthalmic interest, such as the identification of corneal scars in anterior segment images.17 Furthermore, it will also be of interest in other fields of medicine in which there is clinical application of OCT, such as in cardiology for the identification of atherosclerotic plaques.46

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from a NUS Young Investigator Award (MJAG; NUSYIA_FY13_P03, R-397-000-174-133). The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology (NGS). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. This work was presented in part as a talk at the ARVO Imaging of the Eye Conference in May 2016 in Seattle, WA.

Disclosure: J.-M. Mari, None; T. Aung, None; C.-Y. Cheng, None; N.G. Strouthidis, None; M.J.A. Girard, None

References

- 1. Gardiner SK,, Boey PY,, Yang H,, Fortune B,, Burgoyne CF., Demirel S. Structural measurements for monitoring change in glaucoma: comparing retinal nerve fiber layer thickness with minimum rim width and area. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 6886–6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tun TA,, Sun CH,, Baskaran M,, et al. Determinants of optical coherence tomography-derived minimum neuroretinal rim width in a normal Chinese population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 3337–3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chauhan BC,, Danthurebandara VM,, Sharpe GP,, et al. Bruch's membrane opening minimum rim width and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in a normal white population: a multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 2015; 122: 1786–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bussel II,, Wollstein G., Schuman JS. OCT for glaucoma diagnosis. screening and detection of glaucoma progression. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98 Suppl 2: ii15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Girard MJ,, Dupps WJ,, Baskaran M,, et al. Translating ocular biomechanics into clinical practice: current state and future prospects. Curr Eye Res. 2015; 40: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sigal IA,, Wang B,, Strouthidis NG,, Akagi T,, Girard MJ. Recent advances in OCT imaging of the lamina cribrosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98 Suppl 2: ii34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang H,, Ren R,, Lockwood H,, et al. The connective tissue components of optic nerve head cupping in monkey experimental glaucoma part 1: global change. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 7661–7678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fazio MA,, Grytz R,, Morris JS,, Bruno L,, Girkin CA,, Downs JC. Human scleral structural stiffness increases more rapidly with age in donors of African descent compared to donors of European descent. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 7189–7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sigal IA,, Grimm JL,, Jan NJ,, Reid K,, Minckler DS,, Brown DJ. Eye-specific IOP-induced displacements and deformations of human lamina cribrosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang L,, Albon J,, Jones H,, et al. Collagen microstructural factors influencing optic nerve head biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 2031–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coudrillier B,, Pijanka JK,, Jefferys JL,, et al. Glaucoma-related changes in the mechanical properties and collagen micro-architecture of the human sclera. PloS One. 2015; 10: e0131396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coudrillier B,, Geraldes D,, Vo N,, et al. Phase-contrast micro-computed tomography measurements of the intraocular pressure-induced deformation of the porcine lamina cribrosa [published online ahead of print November 30. 2015]. IEEE Trans Med Imaging doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2015.2504440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Grytz R,, Girkin CA,, Libertiaux V,, Downs JC. Perspectives on biomechanical growth and remodeling mechanisms in glaucoma(). Mech Res Commun. 2012; 42: 92–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ayyalasomayajula A,, Park RI,, Simon BR,, Vande Geest JP. A porohyperelastic finite element model of the eye: the influence of stiffness and permeability on intraocular pressure and optic nerve head biomechanics. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2016; 19: 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Girard MJ,, Strouthidis NG,, Ethier CR,, Mari JM. Shadow removal and contrast enhancement in optical coherence tomography images of the human optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 7738–7748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mari JM,, Strouthidis NG,, Park SC,, Girard MJ. Enhancement of lamina cribrosa visibility in optical coherence tomography images using adaptive compensation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 2238–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Girard MJ,, Ang M,, Chung CW,, et al. Enhancement of corneal visibility in optical coherence tomography images using corneal adaptive compensation. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015; 4 3: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Girard MJ,, Tun TA,, Husain R,, et al. Lamina cribrosa visibility using optical coherence tomography: comparison of devices and effects of image enhancement techniques. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghorbel I,, Rossant F,, Bloch I,, Tick S,, Paques M. Automated segmentation of macular layers in OCT images and quantitative evaluation of performances. Pattern Recognition. 2011; 44: 1590–1603. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishikawa H,, Stein DM,, Wollstein G,, Beaton S,, Fujimoto JG,, Schuman JS. Macular segmentation with optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 2012–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Diri B,, Hunter A,, Steel D. An active contour model for segmenting and measuring retinal vessels. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2009; 28: 1488–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koozekanani D,, Boyer K,, Roberts C. Retinal thickness measurements from optical coherence tomography using a Markov boundary model. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2001; 20: 900–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rossant F,, Bloch I,, Ghorbel I,, Paques M. Parallel Double Snakes. Application to the segmentation of retinal layers in 2D-OCT for pathological subjects. Pattern Recognition. 2015; 48: 3857–3870. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baroni M,, Fortunato P,, La Torre A. Towards quantitative analysis of retinal features in optical coherence tomography. Med Eng Phys. 2007; 29: 432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bagci AM,, Shahidi M,, Ansari R,, Blair M,, Blair NP,, Zelkha R. Thickness profiles of retinal layers by optical coherence tomography image segmentation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 146: 679–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cabrera Fernandez D, Salinas HM, Puliafito CA. Automated detection of retinal layer structures on optical coherence tomography images. Opt Express. 2005; 13: 10200–10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garvin MK,, Abramoff MD,, Kardon R,, Russell SR,, Wu X,, Sonka M. Intraretinal layer segmentation of macular optical coherence tomography images using optimal 3-D graph search. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008; 27: 1495–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haeker M,, Wu X,, Abràmoff M,, Kardon R,, Sonka M. Incorporation of regional information in optimal 3-D graph search with application for intraretinal layer segmentation of optical coherence tomography images. In: Karssemeijer N, Lelieveldt B. Information Processing in Medical Imaging: 20th International Conference. IPMI 2007. Kerkrade. The Netherlands. July 2–6. 2007 Proceedings. Berlin. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2007: 607–618. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Shahidi M,, Wang Z,, Zelkha R. Quantitative thickness measurement of retinal layers imaged by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 139: 1056–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen Q,, Leng T,, Zheng L,, et al. Automated drusen segmentation and quantification in SD-OCT images. Med Image Anal. 2013; 17: 1058–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mishra A,, Wong A,, Bizheva K,, Clausi DA. Intra-retinal layer segmentation in optical coherence tomography images. Opt Express. 2009; 17: 23719–23728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baroni M,, Diciotti S,, Evangelisti A,, Fortunato P,, La Torre A. Texture classification of retinal layers in optical coherence tomography. In: Jarm T, Kramar P, Zupanic A. 11th Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biomedical Engineering and Computing. Berlin. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2007: 847–850.

- 33. Rossant F,, Ghorbel I,, Bloch I,, Paques M,, Tick S. Automated segmentation of retinal layers in OCT imaging and derived ophthalmic measures. 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro. Boston, MA: IEEE; 2009: 1370–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta P,, Sidhartha E,, Girard MJ,, Mari JM,, Wong TY,, Cheng CY. A simplified method to measure choroidal thickness using adaptive compensation in enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. PloS One. 2014; 9: e96661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pan B, Qian K, Xie H, Asundi A. . Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: a review. Measurement Science and Technology 2009; 20: 062001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thakku SG,, Tham YC,, Baskaran M,, et al. A global shape index to characterize anterior lamina cribrosa morphology and its determinants in healthy indian eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 3604–3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Girard MJA,, Beotra MR,, Chin KS,, et al. In vivo 3D Strain mapping of the optic nerve head following IOP lowering by trabeculectomy and associations with visual field loss. Ophthalmology 2016; 123: 1190–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee KM,, Kim TW,, Weinreb RN,, Lee EJ,, Girard MJ,, Mari JM. Anterior lamina cribrosa insertion in primary open-angle glaucoma patients and healthy subjects. PloS One. 2014; 9: e114935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sigal IA,, Flanagan JG,, Lathrop KL,, Tertinegg I,, Bilonick R. Human lamina cribrosa insertion and age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012; 53: 6870–6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garvin MK,, Abramoff MD,, Kardon R,, Russell SR,, Wu X,, Sonka M. Intraretinal layer segmentation of macular optical coherence tomography images using optimal 3-D graph search. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008; 27: 1495–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nadler Z,, Wang B,, Wollstein G,, et al. Automated lamina cribrosa microstructural segmentation in optical coherence tomography scans of healthy and glaucomatous eyes. Biomed Opt Express. 2013; 4: 2596–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan MH,, Ong SH,, Thakku SG,, Cheng CY,, Aung T,, Girard MJA. Automatic feature extraction of optical coherence tomography for lamina cribrosa detection. J Image Graphics. 2015; 3: 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang L,, Lee K,, Niemeijer M,, Mullins RF,, Sonka M,, Abramoff MD. Automated segmentation of the choroid from clinical SD-OCT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 7510–7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kajic V,, Esmaeelpour M,, Glittenberg C,, et al. Automated three-dimensional choroidal vessel segmentation of 3D 1060 nm OCT retinal data. Biomed Opt Express. 2013; 4: 134–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Strouthidis NG,, Grimm J,, Williams GA,, Cull GA,, Wilson DJ,, Burgoyne CF. A comparison of optic nerve head morphology viewed by spectral domain optical coherence tomography and by serial histology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51: 1464–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Foin N,, Mari JM,, Davies JE,, Di Mario C,, Girard MJ. Imaging of coronary artery plaques using contrast-enhanced optical coherence tomography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; 14: 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]