Abstract

Despite comprising 0.7% of the world population, South Africa is home to 18% of the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence. Unyielding HIV subepidemics among adolescents threaten national attempts to curtail the disease burden. Should an HIV vaccine become available, establishing its point of entry into the health system becomes a priority. This study assesses the impact of school-based HIV vaccination and explores how variations in vaccine characteristics affect cost-effectiveness.

The cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained associated with school-based adolescent HIV vaccination services was assessed using Markov modeling that simulated annual cycles based on national costing data. The estimation was based on a life expectancy of 70 years and employs the health care provider perspective.

The simultaneous implementation of HIV vaccination services with current HIV management programs would be cost-effective, even at relatively higher vaccine cost. At base vaccine cost of US$ 12, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was US$ 43 per QALY gained, with improved ICER values yielded at lower vaccine costs. The ICER was sensitive to duration of vaccine mediated protection and variations in vaccine efficacy. Data from this work demonstrate that vaccines offering longer duration of protection and at lower cost would result in improved ICER values.

School-based HIV vaccine services of adolescents, in addition to current HIV prevention and treatment health services delivered, would be cost-effective.

INTRODUCTION

Eighteen percent (18%) of the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence can be found in South Africa, making it the unenviable epicenter of the HIV pandemic.1 Unyielding subepidemics of HIV disease concentrated among the historically vulnerable young women and adolescents of sub-Saharan Africa threaten the worldwide gains made in containing the epidemic.2 The disproportionate disease burden, showing a 4-fold increase in HIV prevalence among 15 to 24 year old women between 2005 and 2008, is clearly evident in the South African literature.3 Male are not exempt however. In South Africa, early coital debut among both sexes linked to the realities of forced sex and older partners have been associated with an increased risk of HIV infection.4

South African efforts to improve HIV treatment and prevention have focused on upscaling condom distribution,5 rolling out voluntary medical male circumcision,6 increasing national HIV testing rates, and improving the coverage of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART).7 Despite these efforts, the United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (UNAIDS) reported that South Africa accounted for 16% of global HIV incidence in 2013 and still had a 58% deficit in ART coverage.1,8 Vaccines are widely acknowledged as the most cost-effective intervention in healthcare.9 Despite several earlier HIV vaccine setbacks,10,11 Rerks-Ngarm et al12 tested the first vaccine regimen (RV144/Thai trial) to show moderate vaccine efficacy in humans in Thailand (2009). The study evaluated the use of 2 priming injections of a recombinant canarypox vector (ALVAC-HIV[vCP1521]) administered at baseline, then at weeks 4, 12, and 24. Boosting injections of recombinant glycoprotein 120 subunit vaccines (AIDSVAX B/E) were given at weeks 12 and 24. The prime-boost HIV vaccine regimen resulted in modest efficacy of 31% over 3.5 years, which together with rapid waning of immunity documented in the first year, raised questions regarding the need for booster injections.12 After undergoing modifications to optimize the HIV vaccine regimen by making it Clade C specific and changing the adjuvant, a potential vaccine regimen was entered into Phase I clinical trials at 6 major South African centers under the umbrella of the HIV Vaccine Trial Network (HVTN) 100 study.13

The financial implications of introducing the HIV vaccination strategy into the expanded program of immunization would present a key advocacy tool to decision makers should this vaccine reach fruition.14,15 Essentially, evaluating the cost-effectiveness and long-term impact of the HIV vaccine strategy hinges on the vaccine's entry point into the health care system and delivering vaccines via a sexual and reproductive health platform to adolescents at school has been associated with improved vaccine coverage rates.14–16 South African HIV prevention strategies have yielded limited successes with high HIV incidence rates still being reported.1 Future expansion of the ART program will result in huge financial and human resources to sustain the program.17 It is under this premise that the national government sought to develop a sexual and reproductive health platform at school level targeting primary HIV prevention strategies among adolescents as a key stream of restructuring primary healthcare in the country.18

The aim of this study was to determine the cost-effectiveness of implementing school-based HIV vaccination as part of the current HIV management strategy adopted in the public sector. It also aimed to discern the vaccine and program characteristics that potentially impact this cost-effectiveness by conducting sensitivity analysis.

METHODS

The study methodology was compliant with the reporting guidelines of the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement.19

Study Overview

Nine-year-old children who were attending South African schools in 2012 were eligible for vaccination on a voluntary basis. The introduction of the vaccine intervention coincided with the plans of national health to develop school-based sexual and reproductive health services.18 The intention was to target learners prior to the onset of sexual activity, the rationale behind this being to circumvent any potential exposure to HIV. The cohort was then modeled through a life expectancy of 70 years. The current life expectancy in South Africa is approximately 60.6 years, but this value is likely to be an underestimate for the current cohort and a higher value was modeled.20 The context of the vaccine strategy would be school-based delivery with the vaccines potentially integrated into the Expanded Program of Immunization currently offered in the South Africa. The study adopted the health service provider (provider) perspective. The provider perspective was selected to provide insight into health service delivery and delineated the financial implications of new interventions being introduced into the public health care sector. Finally, when considering the provider perspective, we are able to generate health information that could potentially guide national health decision making. The HIV vaccine regimen currently under study in South Africa in the HVTN 100 study was modeled as a prevention strategy that would potentially reduce the HIV disease burden and subsequent mortality. The vaccination strategies were considered against the system of HIV counseling and testing (HCT) and the national rollout of ART that constituted the standard of care in South Africa.21 In addition, the standard of care included the distribution of condoms and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). It is important to bear in mind that the intervention comprised the vaccination strategy in conjunction with all the components of the standard of care, as the vaccine strategy would never be implemented as a stand-alone program while there were people still requiring access to ART. Economic costs and health outcomes were each discounted at a rate of 3%, with an uncertainty range of 0% to 6% explored. This is in keeping with the recommendations of the World Health Organization CHOosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective (WHO-CHOICE) guidelines.22

Outcome Measures

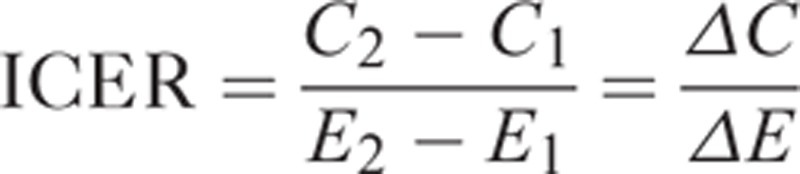

The quality adjusted life year (QALY) was the outcome measure used to draw a comparison between the HIV vaccine intervention and the standard of care. As a standardized measurement from comparative effectiveness research, the QALY incorporates a quality of life “utility score” adjustment that was applied to life expectancy.23 The QALY allows for mortality and morbidity considerations in a single measure, allowing for comparability across studies.24 The outcomes facilitated the calculation of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER represents the difference in costs between strategies and the difference in effects (e.g., QALYs) between strategies (Equation 1). The unit of measurement of the ICER is US$ per QALY gained.

|

where C1 and E1 are the costs and effects of the standard of care (comparator), and C2 and E2 are the costs and effects of the intervention.

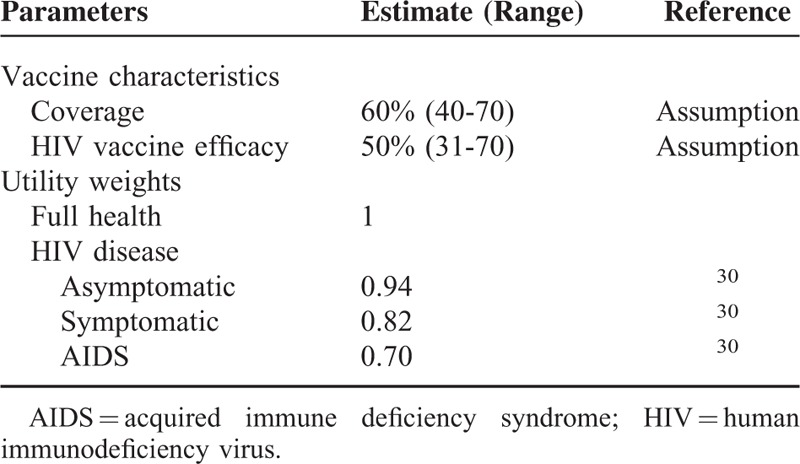

The HIV vaccine modeled was hypothetical. The vaccine characteristics considered in this model (Table 1) were suggested by the target product profile formulated by the Pox-Protein Private-Public Partnership (P5), a collaboration of organizations established to build on the foundations of the RV144/Thai trial.25 The regimen included in this economic evaluation mirrored the ongoing HVN 100 study which adopted the ALVAC prime ALVAC/gp120 boost of the RV144/Thai trial but added an additional ALVAC/gp120 boost at month 12. This boost at month 12 was added to circumvent the waning of the immune response documented in the RV144/Thai trial a year after initial vaccine administration. Additionally, a pivotal phase IIb/III HIV vaccine efficacy trial is planned to take place in South Africa designated HVTN 702, which will evaluate the same regimen (as HVTN 100).

TABLE 1.

HIV Vaccine Characteristics and Disease Utility Weights Adopted

The estimated vaccination coverage was modeled at 60% receiving the initial course. This a guarded estimate on the 68% coverage achieved for the 3rd dose of diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, and pertussis vaccine (DTP3).26 The DTP3 coverage has been validated as a proxy for immunization system strength (performance) as it was available in nearly all countries and years in the recent decades.27 The coverage range was then explored in the sensitivity analysis. The base-case HIV vaccine modeled cost US$ 12 per dose had a vaccine efficacy of 50% and the duration of protection of 10 years (achieved through the administration of annual boosters). The impact of declining immunity demonstrated in the RV144/Thai trial (particularly in the year following administration) indicated the need for booster injections. The declining immunity was countered by the economic evaluation assessing a conservative approach of annual boosters. Although this may not be pragmatic, it merely represented an overestimation of costs in the context of this evaluation. The vaccine price of US$ 12 was roughly based on the public sector human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine pricing (US$ 17). Markedly reduced vaccine prices were justified by the overwhelming burden of HIV disease in the country and by weighing up the delicate issues of accessibility and coverage. Additionally, the prices were deemed plausible given the strides made in negotiating lower priced ART and HPV vaccines in the public sector.28,29 The price assumption was tested in the sensitivity analysis. The utility of HIV related interventions was derived from a meta-analysis of the pooled utilities relating to HIV/AIDS.30 The utility weights for both diseases appear in Table 1.

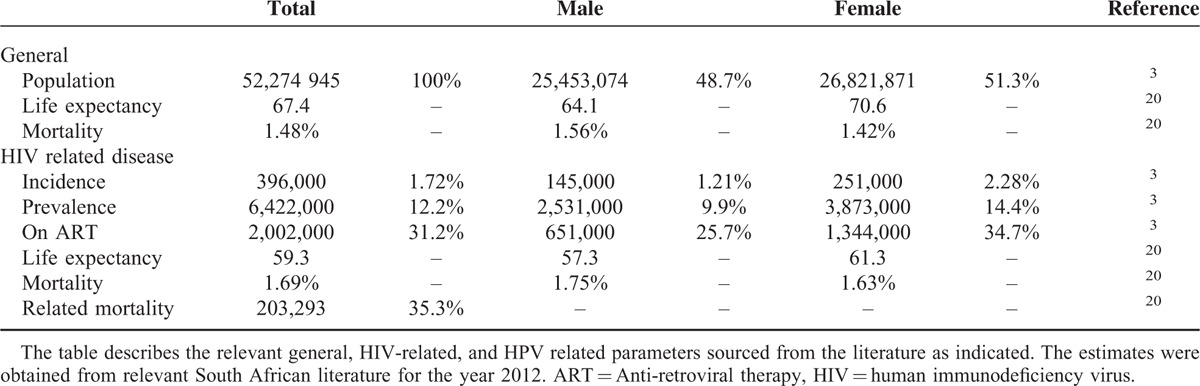

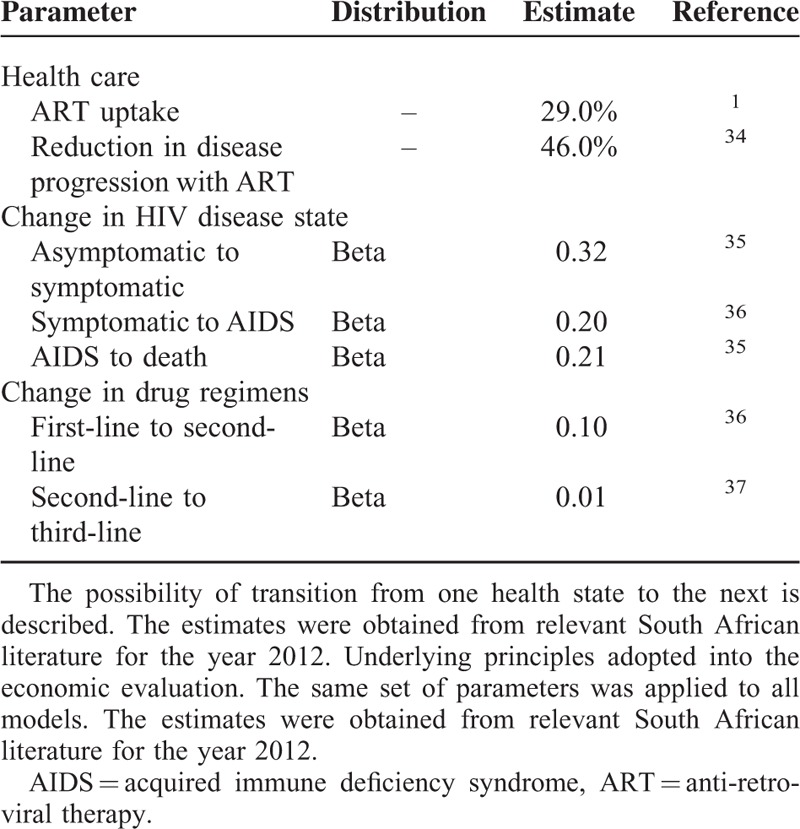

Study Inputs

South African epidemiological data drawn from published literature were used to contextualize the study (Table 2). The disease transition probabilities between HIV disease states were obtained from the relevant South African literature (Table 3). Statistics South Africa has consistently cited mortality figures for HIV/AIDS approximating 3.4% annually, despite unabated increases in deaths among young adults.31,32 In-depth scrutiny suggested these figures underestimated mortality as several conditions known to be HIV/AIDS related (e.g., TB, parasitic diseases, and infectious intestinal diseases) were reported as independent causes of death.33 Based on this inconsistency, the 2012 HIV/AIDS related mortality rates were revised by Statistics South Africa in 2014.20

TABLE 2.

Relevant South African HIV Epidemiology

TABLE 3.

Disease Transition Probabilities Showing Annual Progression Risk

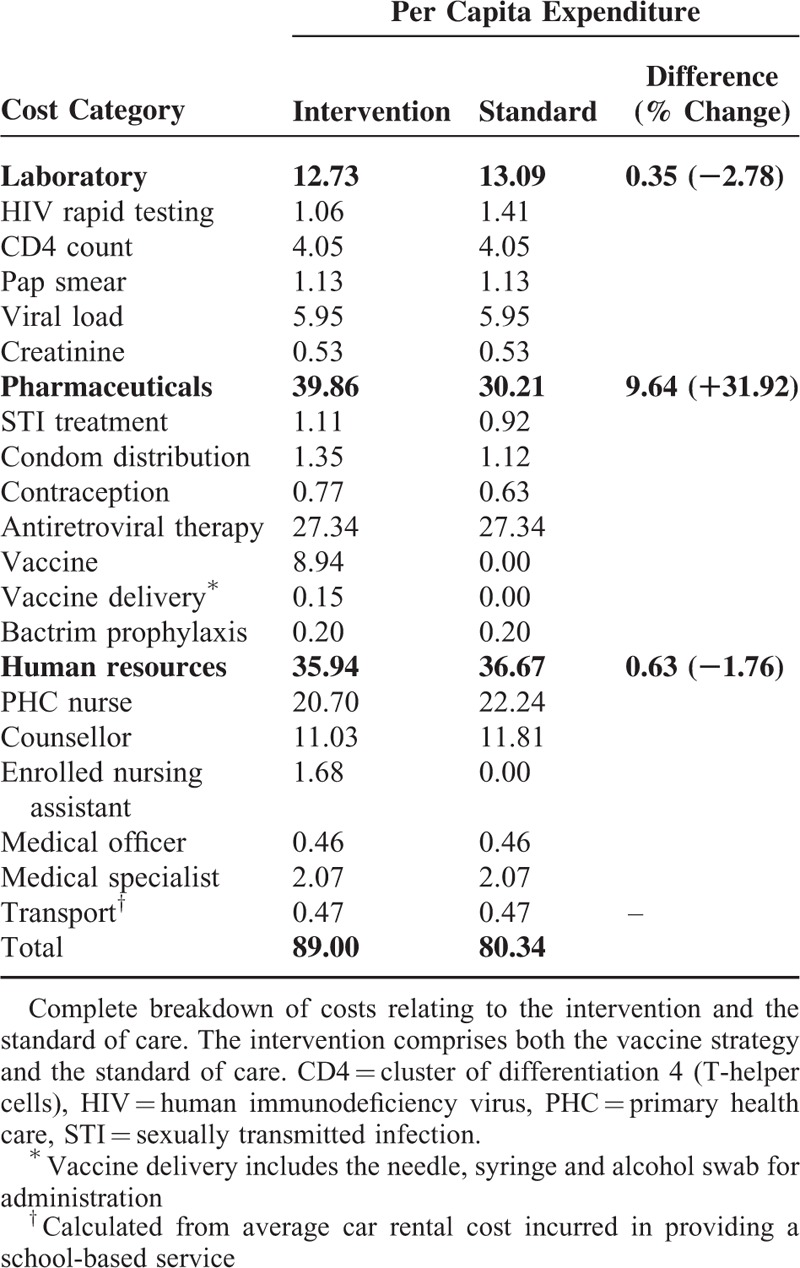

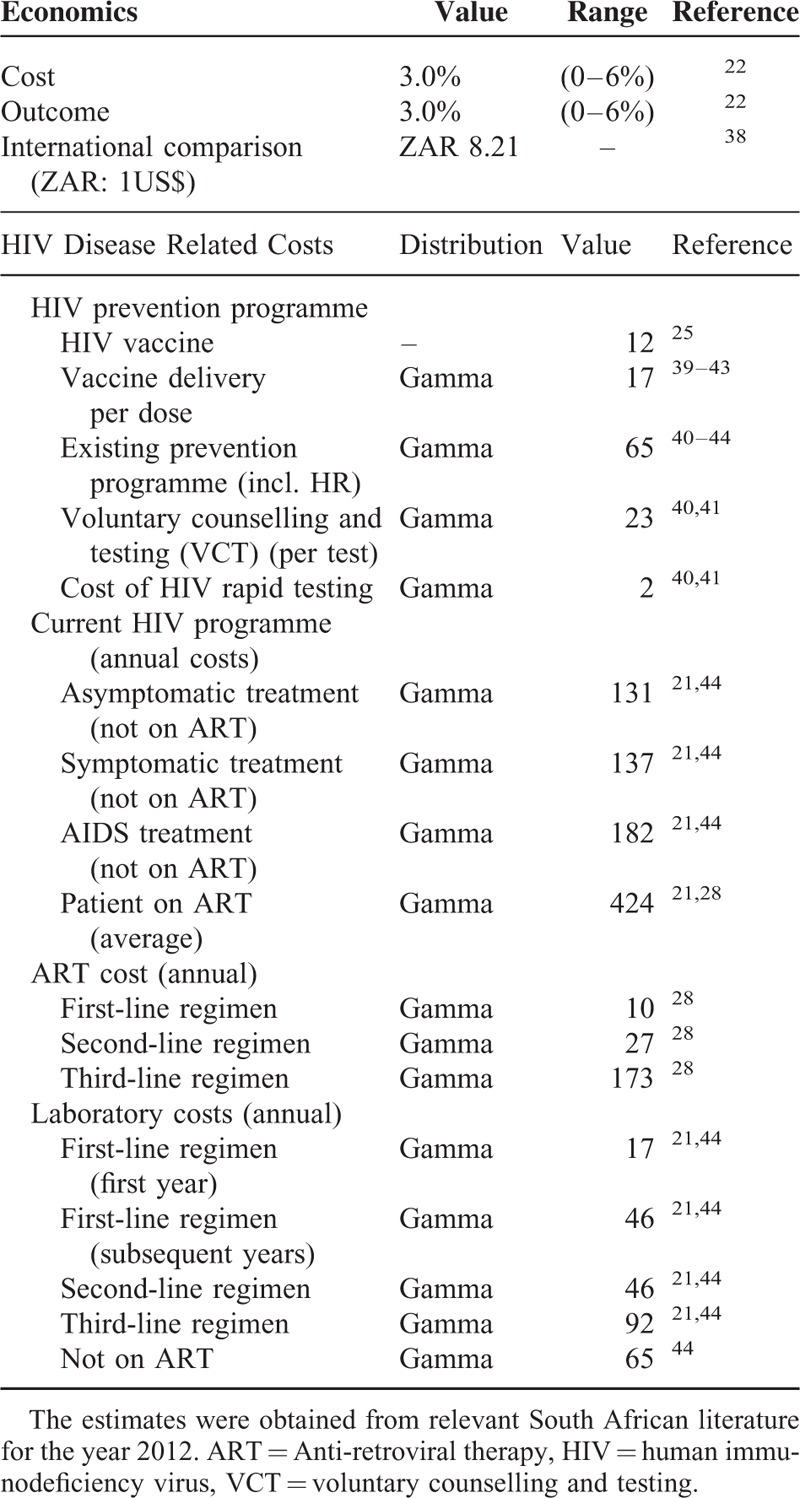

Relevant HIV related cost components were identified from the 2013 South African national HIV treatment guideline.21 Although 2012 was considered the reference year for this study, the 2013 guideline was considered in this model as it included fixed-dose combination therapy (FDC). The FDC was important as it impacted the costing and proposed integrated health management of sexual and reproductive health conditions. Delivery of health services was presumed to be conducted at schools. It was assumed that primary health care nurses would consult general patients, and complicated cases would warrant upward referral to doctors or medical specialists at clinics. All costs were adjusted to the common year 2012. Costs were converted from South Africa rand (ZAR) to United States dollar (US$) to allow for international comparison using the average exchange rate for 2012 (US$ 1 = ZAR 8.21).34 HIV vaccination costs included human resources, counseling (pre- and post-HIV testing), HIV testing, delivery costs (e.g., needles and syringes), and storage costs (Table 4). Pricing of laboratory tests conducted by the National Health Services Laboratory, costing of medication, consumables and additional pharmaceuticals, and valuations of medical personnel cost based on the Uniform Patient Fee Schedule (UPFS) were sourced from the National Department of Health website (www.health.gov.za). Costing parameters were detailed in Table 5.

TABLE 4.

Model Components and Cost Comparison of the HIV Vaccination Program (US$)

TABLE 5.

Parameter Costs and Economic Considerations Used in the Analysis

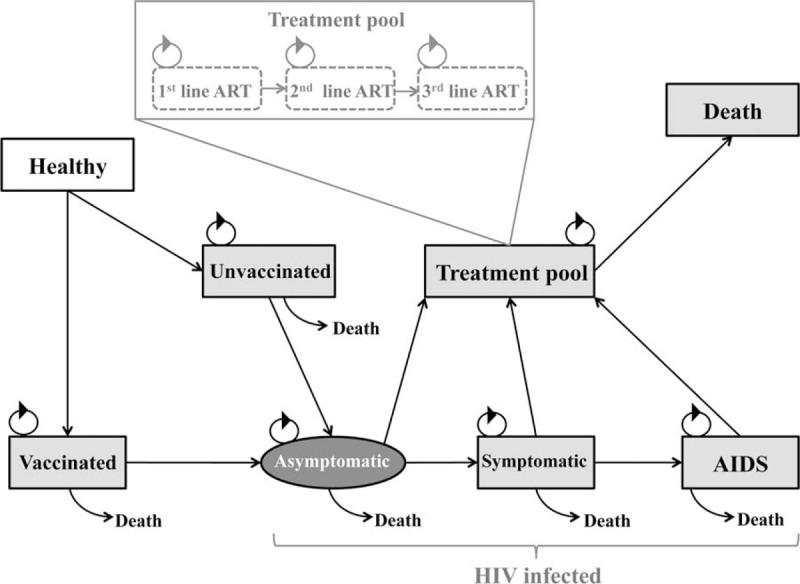

Model-Based Economic Evaluation

Microsoft Excel (Version 2010) (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) was used for data capture and analysis. Ersatz version 1.2 (www.epigear.com), a boot-strap add-in application for Excel, was used to perform the uncertainty analysis. The movement between health states shown in Figure 1 was modeled on the basis of transition probabilities and the effectiveness values of the treatment options in the model. A semi-Markov simulation was constructed showing annual cycles. Semi-Markov models were used as it allowed for the addition of tunnel states to counter the “memoryless” nature of the Markov model. The study population started in the model disease free and was exposed to the risk of acquiring HIV disease annually.

FIGURE 1.

Semi-Markov model of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine strategy. Healthy vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals may enter into a HIV positive state. They can progress from a HIV infection state to the HIV treatment pool. All states may progress to a death states at a rate specific to the state they were currently in.

The model examined the impact of HIV vaccination (intervention) in conjunction with the standard of care in South Africa compared with the standard of care alone among school-going adolescents in South Africa. The model comprised 8 health states (Figure 1). All individuals were considered HIV negative and healthy at the start of the model (State 1). They then moved into a vaccinated (State 2) or unvaccinated (State 3) state depending on the coverage rate. Individuals in either of these states may transition into an asymptomatic HIV state (State 4), where they would receive ART if required. This is represented by the oval shape to emphasize that this is a primary endpoint. From an asymptomatic state, individuals may progress to a symptomatic (State 5) or AIDS (State 6) state. Each of the HIV infected states may enter a treatment pool (State 7). The treatment pool was subcategorized into 1st, 2nd, and 3rd ART line regimens, each with a possibility of progressing to death. Every aforementioned health state may progress to death with different transition probabilities (State 8). During each cycle there was a probability of remaining in the current health state or progressing to another. The arrows represented the transition probabilities from one state to another. Costs and utility measures were then added to each health state and the model was able to predict costs and QALYs over the 70-year period for the intervention and the standard of care. Once the vaccine had been stopped, event rates were assumed to be the same for both arms of the study.

One-way sensitivity analyses evaluated the impact of single assumptions on cost and outcomes. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) with a bootstrapping technique was used to explore the uncertainty in the model and evaluate the robustness of the results. The PSA was characterized by a 2nd order, 1000 iteration Monte Carlo simulation yielding a range of plausible values for lifetime costs, QALYs, and ICER. The PSA results were used to calculate the 95% confidence interval around the model outcomes, and these results were represented in the form of the cost effectiveness acceptability curve. As South Africa does not have a predefined willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold, the gross domestic product per capita (2012) was used as a proxy in accordance with the WHO Guide to Cost-Effective Analysis.22,35,36 The WTP threshold was thus defined as US$ 7508 (ZAR 61,641) per QALY gained.

All participants were presumed sexually naive at the start of the model. The model assumed that children eligible for schooling were attending school and thus drop-out rates were considered. It was further assumed that HCT services in the school environment were universally provided and easily accessible as described in the national policy.37 The modeling exercise contextualized the national rollout of the HIV vaccination strategy under the umbrella of an established school-based programme providing comprehensive care to all socio-economic levels of learners. Last, the model assumed that the school-based program would be well utilized by learners presumably as the provision of care occurred in a familiar and safe environment without encroaching on school attendance. There remains no validation of this assumption as no formal pilot studies assessing uptake of care have been conducted.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand.

RESULTS

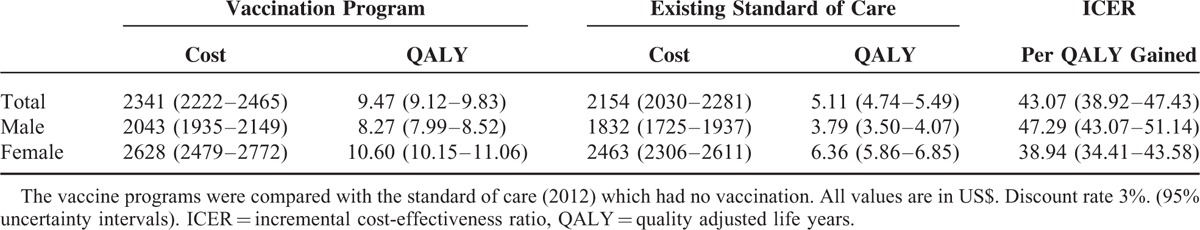

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

The total costs and QALYs gained in the lifetime of the hypothetical cohort for HIV vaccine interventions are shown in Table 6. Compared with the existing program (which has no vaccination), the introduction of the HIV vaccination in the general adolescent population resulted in the net cost of US$ 187 representing an 8.68% increase in costs. This translated to 4.36 QALYs gained and an ICER of US$ 43.07 per QALY gained (95% CI: US$ 38.92–47.43). Administering the vaccine to female only yielded a 68% increase in QALYs gained to 6.36 (95% CI: 5.86–6.85) compared with administering to males only. The greater impact of the intervention among the female population was unsurprizing given their substantially higher burden of disease. Generally, the implementation of the HIV vaccine program does represent an increase in total spending but with significant improvement in life-years.

TABLE 6.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the HIV Vaccine Intervention

Sensitivity Analyses

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis

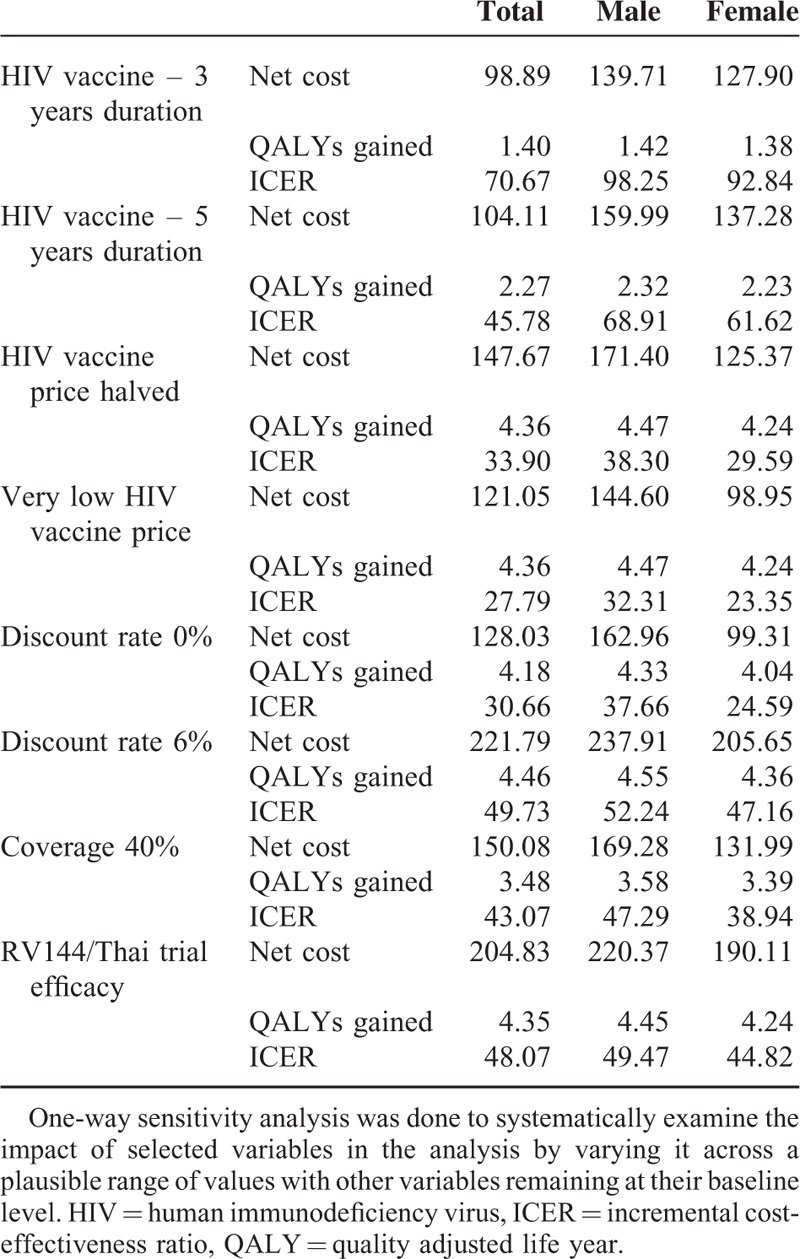

In a one-way sensitivity analysis, a single parameter is varied to demonstrate its impact on overall cost-effectiveness.38Table 7 identified the improved ICER outcomes associated with increasing the duration of vaccine protection and lower vaccine pricing strategies. The discount rate greatly influenced the cost-effectiveness with 6% discounting resulting in a 62.20% increase in the ICER value compared with 0% discounting. This was largely attributed to the investment for the intervention being made now (present costs) with benefits only being realized much later (future implications). Last the analysis showed that a partially effective vaccine or one that has coverage less than 50% would still prove cost-effective compared with the proxy WTP estimate considered for South Africa.

TABLE 7.

Scenario Analyses Compared With Base Findings

Two-Way Sensitivity Analysis

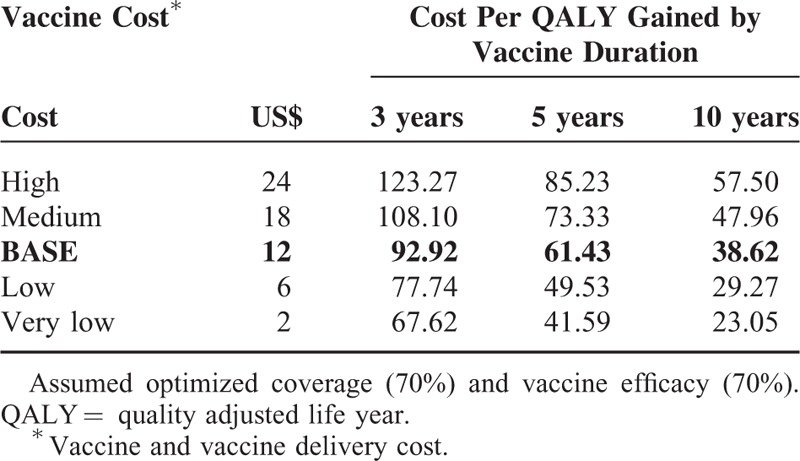

The ideal HIV vaccine would be highly efficacious and affordable. The two-way analysis in Table 8 explored the effects of varying the vaccine cost and vaccine duration of protection on the ICER; under the optimized conditions of vaccine efficacy and vaccine coverage fixed at 70% each. Lower priced vaccines yielded more cost-effective results. Vaccines with a longer duration of action (10 years) outperformed the shorter acting vaccines (at 5 or 3 years duration) irrespective of price.

TABLE 8.

Two-Way Analysis of Cost and Duration

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis

Cost-Effectiveness Plane

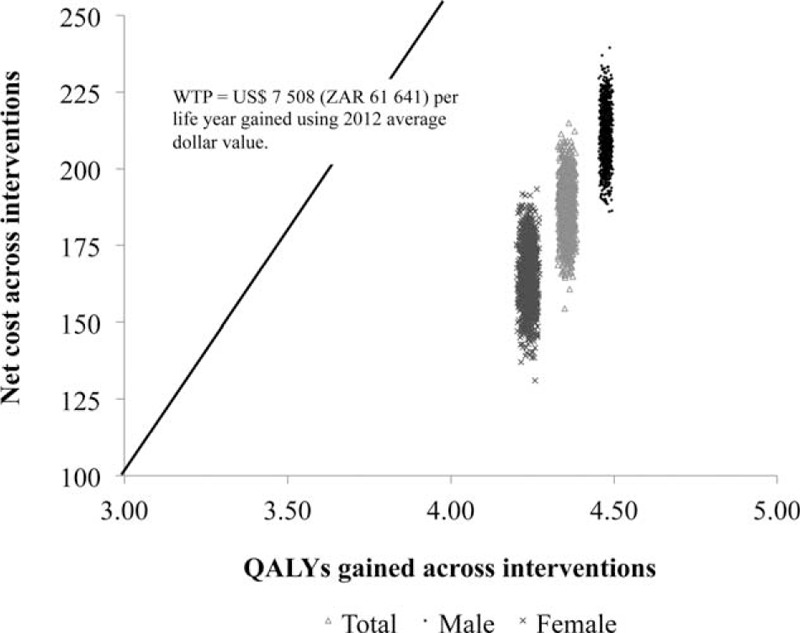

The HIV vaccine program implementation suggests improved health outcomes at a greater cost compared with the current standard of HIV care in the public sector. Bootstrapping analysis undertaken by repeated sampling (1000 iterations) estimated the uncertainty in model costs and effects (Figure 2). The majority of the iterations lying in the north east (NE) quadrant of the cost-effectiveness (CE) plane (an area of trade-off indicating greater health gain for added expenditure) raises the critical issue of determining how much a decision maker is prepared to pay for an additional unit gain in health outcome. The limited vertical variation indicates limited variability associated with treatment costs. The reported ICERs for all 3 plausible interventions remained well below the WTP threshold and were thus deemed cost-effective.

FIGURE 2.

The cost-effectiveness plane. The incremental costs and effects were represented visually using the incremental cost-effectiveness plane. The x-axis divides the plane according to incremental cost (positive above, negative below), while the y-axis divides the plane according to incremental effect (positive to the right, negative to the left). The axes divide the incremental cost-effectiveness plane into 4 quadrants through the origin. All values falling below the WTP threshold indicted are cost-effective.

Cost Effectiveness Acceptability Curve

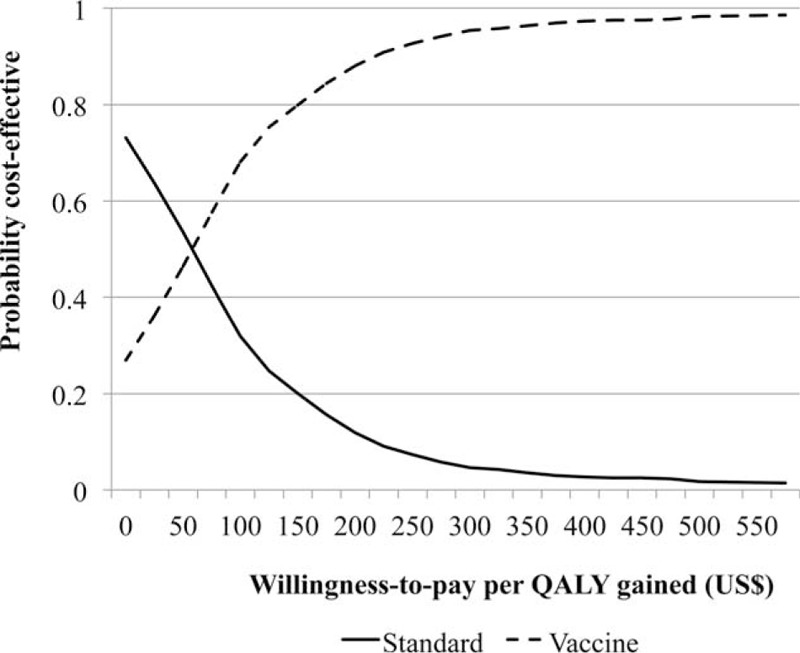

The cost effective acceptability curve (CEAC) (Figure 3) was constructed by calculating the probability that the intervention implemented in the general population represents the optimal choice across the 1000 simulations, for selected willingness-to-pay governmental thresholds (x-axis: US$ 100 increments of cost per 1 QALY gained). The curve indicates the intervention to be cost effective and supports the implementation of the vaccine program as it has resulted in improved health outcomes.

FIGURE 3.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. The CEAC shows the proportion of simulations that would be cost-effective (y-axis) given different threshold values of cost per QALY gained (x-axis). CEAC = cost effective acceptability curve, QALY = quality adjusted life year.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the cost per QALY gained, expressed as the ICER, and associated with school-based adolescent HIV vaccination services using a Markov modeling approach. The model simulated annual cycles based on local costing data and transition probabilities derived from the literature. The findings support that, even at relatively higher vaccine cost, the simultaneous implementation of the HIV vaccine program together with the ART rollout would prove cost-effective. These findings were confirmed by the cost-effectiveness plane and CEAC findings.

The ICER was clearly sensitive to cost variations in the uncertainty analysis. Relatively lower prices were considered in this analysis, as the South African government had successfully negotiated discounts with pharmaceutical companies in the past, notably with ART and HPV vaccines.28,29 It is difficult to interpret the impact that these discounts would have on cost-effectiveness as discounts are frequently negotiated on volumes rather than prices.38 The ICER in this study also demonstrated particular sensitivity to variations in vaccine efficacy. The cost-effectiveness of an HIV vaccine has been shown to be highly influenced by vaccine efficacy.39–41 In fact, even before the realization of the RV144/Thai trial work, computer simulations of HIV transmission dynamics among South African adolescents underscored the important role of partially effective HIV vaccines irrespective of other public policy interventions.42 Work by Owens et al41 illustrated how varying degrees of vaccine efficacy for susceptibility, disease progression and infectivity still yielded substantial health benefits, even with only modestly efficacious vaccines. Based on the short-lived vaccine efficacy described by Rerks-Ngarm et al,12 annual booster vaccinations were accounted for in the study model. As booster vaccinations were not assessed in the RV144/Thai study, the analyses of the booster vaccination in this study remain hypothetical.12

The two-way sensitivity analysis (Table 8) conducted reiterate that HIV vaccines of longer duration would provide more robust protection. Andersson cautioned against the high numbers of booster vaccinations that would be required to maintain population coverage levels despite having demonstrated significant impact on the South African epidemic when applying the RV144 vaccine using demographic projections.43 Modeling work with partially efficacious vaccines by Phillips returned similar health benefits in a Southern African setting but offered no commentary on booster vaccinations.44 It should be borne in mind that the quadruple burden of noncommunicable disease, communicable, maternal and child health, and injury-related disorders place insurmountable pressure on a dwindling South African health budget.45 As such, the cost of implementing a partially efficacious HIV vaccine requiring several boosters must be weighed against the equity of scarce financial resource allocation.

The study findings should be considered in light of potential limitations. The study accounted for heterosexual transmission of HIV only. Same sex HIV transmission was excluded due to lack of the availability of reliable data. Additionally, the study lacked more representative data on HIV risk and mortality profiles due to poor availability. The study is unable to account for any potential benefit that may arise against disease acquisition and progression once vaccine recipients become HIV infected. However, there were no significant differences reported between vaccinated and unvaccinated arms of the RV144/Thai trial participants who seroconverted in terms of viral load or CD4 counts.12 The study assumed a high coverage rate (70%) but did not account for the potential benefits of herd immunity. The effect of herd immunity could feature prominently in bolstering HIV vaccine coverage rates in a country where the childhood immunization vaccine coverage rates fall significantly short of the required targets.26 Including herd immunity into the model could potentially equate to improved vaccine efficacy and cost-effectiveness. The analysis considered the provider perspective and not the societal perspective. South African health outcomes remain poor compared with similar middle-income counties despite the 8.5% allocation of the country's gross domestic product to health expenditure.46 Although the 8.5% expenditure exceeds the 5% recommendation of the World Health Organization, middle income countries such as Brazil report better health outcomes despite the same proportional expenditure.47 Vaccine implementation would significantly impact the health budget through direct medical costs. This is a major consideration as the vaccine still proved cost-effective at higher prices in the sensitivity analysis. Importantly however, the assessment of the societal benefit would yield important information on increased economic productivity due to infections averted.40

The vaccine was modeled on evidence-based disease parameters as the candidate vaccine is still undergoing clinical trials. HIV vaccination as a preventive strategy was assessed in isolation in this study. It is considered that the simultaneous use of multiple HIV prevention strategies would prove more substantive in the clinical setting.48 HIV vaccination among adolescents is predicted to result in considerable health benefits and to be cost-effective in the South African context. The generalizability of these results is limited by 2 important caveats. First, South Africa does not have a predefined WTP threshold, so while the WTP does not represent an explicit national decision making tool, it highlights the need for due consideration of the intervention by policy makers. Second, as only South African data were modeled and purely from a provider perspective, caution should be exercised when applying these results to other settings. The findings of this analysis suggest that at the conventionally defined WTP threshold in South Africa, the school-based implementation of HIV vaccine services would be cost-effective should the HIV vaccine become commercially available.

Cost impacts and inefficiencies beyond those considered in this analysis may arise once an HIV vaccine is applied in a clinical setting. It would be valuable to reassess the health economic impact accordingly.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, ART = antiretroviral therapy, HVTN = HIV Vaccine Trial Network, ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, PHC = primary health care, PSA = probabilistic sensitivity analysis, QALY = quality adjusted life year, STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Meetings at which parts of the data was presented: The price of prevention: Including HIV vaccines into South African health programmes.

Conference: South African AIDS Conference, International Convention Centre

City & date: Durban, South Africa (9 - 12 June 2015)

Is a HIV vaccine a viable option in South Africa and at what cost?

Conference: HIV Research for Prevention Conference

City & date: Cape Town, South Africa (28 - 31 October 2014)

The potential cost-effectiveness of adding a HIV vaccine to the HIV treatment and prevention programme in South Africa.

Conference: Southern African HIV Clinicians Society Conference

City & date: Cape Town, South Africa (24-27 September 2014)

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) U.S. Public Health Service Grants UM1 AI068614 [LOC: HIV Vaccine Trials Network] as part of the South African HVTN AIDS Vaccine Early Stage Investigator Program (SHAPe).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The Gap Report. UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/20140716_UNAIDS_gap_report (accessed Nov 10, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyrer C, Abdool Karim Q. The changing epidemiology of HIV in 2013. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013; 8:306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettifor A, O’Brien K, MacPhail C, et al. Early coital debut and associated risk factors among young women and men in South Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009; 35:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beksinska ME, Smit JA, Mantell JE. Progress and challenges to male and female condom use in South Africa. Sex Health 2012; 9:51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Department of Health. South African National Implementation Guidelines for Medical Male Circumcision. National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa; 2011. https://www.devex.com/projects/tenders/voluntary-medical-male-circumcision-service-delivery-and-technical-assistance-project-in-south-africa/75903 (accessed Nov 12, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2012. UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland; 2012. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2434_WorldAIDSday_results_en_1.pdf (accessed Feb 09, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Department of Health. National Strategic Plan on HIV, STIs and TB 2012–2016. SANAC, Pretoria, South Africa; 2011. http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/MediaLib/Downloads/Home/Publications/SANACCallforNominations/A5summary12-12.pdf (accessed Jan 13, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozawa S, Mirelman A, Stack ML, et al. Cost-effectiveness and economic benefits of vaccines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine 2012; 31:96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Fitzgerald DW, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 2008; 372:1881–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElrath MJ, De Rosa SC, Moodie Z, et al. HIV-1 vaccine-induced immunity in the test-of-concept Step Study: a case-cohort analysis. Lancet 2008; 372:1894–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAXto Prevent HIV-1 Infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2209–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liefman LS. NIH-Sponsored HIV Vaccine Trial Launches in South Africa – Early Stage Trial Aims to Build on RV144 Results. 2015; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases:http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-sponsored-hiv-vaccine-trial-launches-south-africa (accessed April 16, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob M, Bradley J, Barone MA. HPV vaccines: what does the future hold for preventing cervical cancer in resource-poor settings through immunization programs? Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32:635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ault K, Reisinger K. Programmatic issues in the implementation of an HPV vaccination programme to prevent cervical cancer. Int J Infect Dis 2007; 11:S26–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bugenske E, Stokley S, Kennedy A, et al. Middle school vaccination requirements and adolescent vaccination coverage. Pediatrics 2012; 129:1056–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray A, Conradie F, Crowley T, et al. Improving access to antiretrovirals in rural South Africa – a call to action. S Afr Med J 2015; 105:638–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Department of Health. Provincial Guidelines for the Implementation of the Three Streams of PHC Re-engineering. National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa; 2011. http://www.cmt.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/GUIDELINES-FOR-THE-IMPLEMENTATION-OF-THE-THREE-STREAMS-OF-PHC-4-Sept-2.pdf (accessed Oct 6, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2013; 11:1478–7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2014. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa; 2014. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022014.pdf (accessed Sep 09, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Department of Health. The South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines 2013. National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa; 2013. http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/2013%20ART%20Guidelines-Short%20Combined%20FINAL%20draft%20guidelines%2014%20March%202013.pdf (accessed Apr 06, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan-Torres Edejer T, Baltussen R, Adam T, et al. Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost Effectiveness Analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth JA, Billings P, Ramsey SD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a 14-gene risk score assay to target adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2014; 19:466–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3ed ed.London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell N, Marovich M. P5 Update and GAC Progress Report. Paper presented at: Pox-Protein Private-Public Partnership (P5) Update and Global Access Committee RSA Summit, Oct 20, 2015; Cape Town International Conference Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2015 global summary. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; 2013. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/coverages?c=ZAF (accessed Jan10, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shearer JC, Stack ML, Richmond MR, et al. Accelerating policy decisions to adopt haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine: a global, multivariable analysis. PLoS Med 2010; 7:1000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kardas-Nelson M, Goswami S. Upping the competition. NSP Review. 2013; 6 (May-June):26–9. http://www.nspreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NSP-review-6-web.pdf (accessed Jan 09, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen A, Datta SD, Schwalbe N, Summers D, Adlide G, and the GAVI Alliance. Working towards affordable pricing for HPV vaccines for developing countries: The role of GAVI. GTF.CCC Working Paper and Background Series, No. 3, Harvard Global Equity Initiative, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tengs TO, Lin TH. A meta-analysis of utility estimates for HIV/AIDS. Med Decis Making 2002; 22:475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groenewald P, Nannan N, Bourne D, et al. Identifying deaths from AIDS in South Africa. AIDS 2005; 19:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics South Africa. Mortality and Causes of Death in South Africa, 2012: Findings from Death Notification. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa; 2014. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932012.pdf (accessed Oct 12, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skingsley A, Takuva S, Brown A, et al. Monitoring HIV-related mortality in South Africa: the challenges and urgency. Communicable Dis Surveillance Bull 2014; 12:116–120. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org (accessed Jun 12, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badri M, Maartens G, Mandalia S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volmink HC, Bertram MY, Jina R, et al. Applying a private sector capitation model to the management of type 2 diabetes in the South African public sector: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Department of Health. HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) Policy Guidelines. National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa; 2010. http://www.genderjustice.org.za/publication/national-hiv-counselling-and-testing-hct-policy-guidelines/ (accessed Nov 11, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedden L, O’Reilly S, Lohrisch C, et al. Assessing the real-world cost-effectiveness of adjuvant trastuzumab in HER-2/neu positive breast cancer. Oncologist 2012; 17:164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bos JM, Postma MJ. The economics of HIV vaccines: projecting the impact of HIV vaccination of infants in sub-Saharan Africa. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19:937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leelahavarong P, Teerawattananon Y, Werayingyong P, et al. Is a HIV vaccine a viable option and at what price? An economic evaluation of adding HIV vaccination into existing prevention programs in Thailand. BMC Public Health 2011; 11:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owens DK, Edwards DM, Cavallaro JF, et al. The Cost Effectiveness of Partially Effective HIV Vaccines. In: Brandeau ML, Sainfort F, Pierskalla WP. eds. Operations Research and Health Care – A Handbook of Methods and Applications. Vol 70, US: Springer; 2004:403–418. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amirfar S, Hollenberg JP, Abdool Karim SS. Modeling the impact of a partially effective HIV vaccine on HIV infection and death among women and infants in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 43:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson KM, Paltiel AD, Owens DK. The potential impact of an HIV vaccine with rapidly waning protection on the epidemic in Southern Africa: examining the RV144 trial results. Vaccine 2011; 29:6107–6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Nakagawa F, et al. Potential future impact of a partially effective HIV vaccine in a Southern African setting. PloS One 2014; 9:e107214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayosi BM, Flisher AJ, Lalloo UG, et al. The burden of non-communicable diseases in South Africa. Lancet 2009; 374:934–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Department of Health. National Health Act (61/2003): Policy on National Health Insurance, 34523. National Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa; 2010. https://www.greengazette.co.za/documents/national-gazette-34523-of-12-august-2011-vol-554_20110812-GGN-34523.pdf (accessed Sep 12, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savedoff WD. What should a country spend on health care? Health Aff 2007; 26:962–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long EF, Owens DK. The cost-effectiveness of a modestly effective HIV vaccine in the United States. Vaccine 2011; 29:6113–6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]