Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a deadly disease, commonly arises in the setting of chronic inflammation. C-C motif chemokine ligand2 (CCL2/MCP1), a chemokine that recruits CCR2-positive immune cells to promote inflammation, is highly upregulated in HCC patients. Here, we examined the therapeutic efficacy of CCL2-CCR2 axis inhibitors against hepatitis and HCC in the miR-122 knockout (aka KO) mouse model. This mouse model displays upregulation of hepatic CCL2 expression, which correlates with hepatitis that progress to HCC with age. Therapeutic potential of CCL2-CCR2 axis blockade was determined by treating KO mice with a CCL2 neutralizing antibody (nab). This immunotherapy suppressed chronic liver inflammation in these mice by reducing the population of CD11highGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells, and inhibiting expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in KO livers. Furthermore, treatment of tumor-bearing KO mice with CCL2 nab for 8 weeks significantly reduced liver damage, HCC incidence and, tumor burden. Phospho-STAT3 (Y705) and c-MYC, the downstream targets of IL-6, as well as NF-κB, the downstream target of TNF-α, were downregulated upon CCL2 inhibition, which correlated with suppression of tumor growth. Additionally, CCL2 nab enhanced hepatic NK cell cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production, which is likely to contribute to the inhibition of tumorigenesis. Collectively, these results demonstrate that CCL2 immunotherapy could be an effective therapeutic approach against inflammatory liver disease and HCC.

Keywords: microRNA-122 (miR-122), Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), CCL2 neutralizing antibody, CD11bhighGr1+ cells, Natural killer (NK) cells

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common liver cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1, 2). The incidence of HCC has tripled in the United States because of the precipitous increase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the past twenty years (3, 4). Furthermore, sorafenib, the only FDA approved drug for advanced HCC extends overall survival by only 2.8 months (5). Recent clinical trials have shown that it is ineffective as an adjuvant therapy after resection or ablation of the tumor (6). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of HCC.

MicroRNA-122 (miR-122) is the most abundant liver-specific microRNA in vertebrates and loss of miR-122 is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis in HCC patients (7). We previously found that development of spontaneous HCC with age mimicked different stages of tumor progression (e.g. steatohepatitis, fibrosis, primary and metastatic HCC) in miR-122 knockout (KO) mice (8, 9). We also observed that miR-122 depletion in the mouse liver leads to upregulation of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), which recruits CCR2+CD11bhighGr1+ immune cells to the liver (8). These cells, in turn, produce proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α in the liver, resulting in hepatitis and eventually HCC.

CCL2 is known to be involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases characterized by monocytic infiltrates, such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis (10, 11). CCL2 also promotes local inflammation and macrophage infiltration in the chronically injured liver (12). Very recently, Li et al. demonstrated that a chemical inhibitor of CCR2, the receptor of CCL2, inhibited HCC development by reducing monocytes/macrophage infiltration and M2-macrophage polarization as well as CD8+ T cell activation in the murine xenograft model (13). However, whether targeting the CCL2-CCR2 axis by immunotherapy could be an effective therapeutic approach against chronic inflammation and HCC has not been addressed. In the present study, we addressed this important question using a novel preclinical model, miR-122 knockout mice that develop chronic inflammation driven HCC (8). Our results clearly showed that targeting CCL2-CCR2 signaling by CCL2 immunotherapy could be an alternative approach in suppressing hepatitis and HCC development. Furthermore, our studies revealed that CCL2 neutralizing antibody (nab) immunotherapy in miR-122 KO mouse model involves suppression of CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells recruitment and enhancement of NK cell cytotoxicity. These observations underscore the importance of targeting CCL2-CCR2 axis as a potential therapy in a subset of human HCC patients with chronic hepatic inflammation and high CCL2.

Materials and Methods

Treatment of miR-122 KO mice with CCL2 antibody and CCR2 inhibitor

miR-122 KO mice were generated as described (8). Animals were housed in Helicobacter-free facility under a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle. Animals were handled following the guidelines of the Ohio State University Institutional Laboratory Animal Care Committee.

CCL2 neutralizing antibody (anti-mouse CCL2; clone C1142) was generously provided by Janssen (14). miR-122 KO mice were injected intraperitoneally (ip) with CCL2 nab (2mg/kg). The control group was injected with vehicle (PBS). To study the function of CCL2 in hepatitis, 4-month-old KO mice were treating with CCL2 nab twice a week for 4 weeks. To study the role of CCL2 in HCC development, 12-month-old KO mice were injected with CCL2 nab twice a week for 8 weeks.

CCR2 inhibitor (Tocris Bioscience, cat# 2089) was given to KO mice in the drinking water daily (10mg/kg) for 4 weeks. The control group for CCR2 inhibitor was fed with regular water.

Flow cytometric analysis

Murine mononuclear cells from livers were isolated as previously described (8, 15). Erythrocytes were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Cells isolated from livers were treated with Fc Block antibody (anti CD16/32, BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with mouse-specific immune cell surface markers for 30 min at 4°C. The following anti-mouse antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200: CD3-APC, CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5, NK1.1-APC, NK1.1-PE, CD19-FITC, CD69-FITC, CD27-PE-Cy7, CD11b-PE, CD11b-PerCP-Cy5.5, Gr1 V450 and IFN-γ-FITC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). For staining of IFN-γ, cells were treated with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) following initial cell-surface staining and then performed intracellular staining.

NK cytotoxicity assay

Tumor-derived NK cells were enriched by NK cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) and then sorted using a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Hepa1-6, a mouse hepatoma cell line was generously provided by Dr. Gretchen Darlington (Baylor College of Medicine). Although we did not authenticate these cells, they exhibited characteristics and gene expression profile of mouse hepatma cells. Hepa cells were labeled with Chromium-51 (Cr-51) and then pre-incubated with C1142 antibody or isotype antibody at a concentration of 10μg/ml for 1h. Then a standard 4-hour Cr-51 release assay (16) was performed to access cytotoxicity of mouse NK cells against Hepa cells.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), mouse serum was collected by mandibular punch (before treatment) or cardiac punch (after treatment). KO mouse older than 10 months old would be monitored for their body weight and serum AFP level by every two weeks. AFP level was quantified by DRG® AFP (Alpha Fetoprotein) kit (DRG, cat# EIA-1468).

For IFN-γ, mouse liver mononuclear cells were isolated as previously described (8, 15). Hepa cells cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, were pre-incubated with C1142 (CCL2 nab) at a concentration of 10μg/ml for 1h. Then, 106 mononuclear cells were incubated with the same number of Hepa cells per well in a 96-well V-bottom plate at 37°C for 24h. Culture supernatants were collected for IFN-γ estimation using mouse IFN-γ ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience, cat# 88-7314-88).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI of liver tumors in miR-122 KO mice was performed as described (17).

Serological, histological and immuno-histochemical (IHC) analysis

Serum was isolated from mice by cardiac puncture after CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation and stored at −80°C. Biochemical analysis of serum enzymes was performed using VetAce (Alfa Wassermann system) as described (8). Macroscopic tumors were counted, dissected and weighed along with benign liver tissues. A fraction of tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde as described (8) and the rest was snap-frozen for RNA and protein analysis.

For histology, paraffin embedded tissue sections (4μm) on glass slides were stained with H&E or IHC analysis with Ki-67, AFP, and Glypecan3 (GPC3) specific antibodies as described (8). Inflammation score was generated through blinded evaluation of H&E stained slides (x 100 magnification) as described previously (8). IHC analysis was done as described (8) and quantified by ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Microscopic images were taken by phase contrast microscope (BX41TF, OLYMPUS) and camera (DP71, OLYMPUS). CellSens Standard 1.13 (OLYMPUS) software was used to capture images. Antibody information is provided in the supplement.

Reverse transcription - quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue using TRIzol (Life Technologies, cat#15596018) followed by DNase I treatment. DNase-treated RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using High-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystem, cat# 4368813). RT-qPCR analysis of each sample performed in triplicate was performed using SYBR Green chemistry. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh. Relative expression was calculated by ΔΔCT method. Primer sequences are provided in the Supplementary Table 1.

Immunoblot analysis

Proteins were extracted from whole liver and tumor tissues by SDS lysis buffer followed by immunoblotting with primary antibodies (8). Signals were developed using Pierce ECL reagent (ThermoFisher, cat# 32106) and quantified by ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Antibody information is provided in the supplement.

Statistical Analysis

All bar diagrams are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Two sample t-tests or ANOVA were used for analysis for comparison of two or more groups. For the GEO data analysis, CCL2 expression from the quantile-normalized data was compared among tumor tissue types with ANOVA. Holm’s procedure was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the difference of tumor incidence and tumor size between the CCL2 nab treated and vehicle treated groups. P-values <0.05 were considered significant and represented as asterisks.

Results

CCL2 is upregulated in primary human HCC

To verify whether CCL2 plays a role in human HCC development, we first examined its expression across independent microarray datasets (HCC vs. normal liver) downloaded from Oncomine™ (18). To validate CCL2 expression, we chose The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Mas liver, and Guichard liver that contain large patient cohorts (18–20). CCL2 DNA copy number or mRNA expression showed a significant increase in tumor tissues compared to the adjacent benign liver across four datasets (Table 1) (18–20). To further evaluate CCL2 expression and disease prognosis, we analyzed HCC RNA microarray data (n=115, mainly HCV positive) from GEO database (GSE14323) (20). The results showed that CCL2 RNA expression was significantly elevated in HCCs, cirrhotic livers, and cirrhotic HCCs compared to normal livers (Fig. 1). These data imply that CCL2 might be critical for progression to cirrhosis and HCC. Thus, blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis seems to be a reasonable therapeutic approach for HCC or even early stages of HCC development such as hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Table 1.

CCL2 expression across 4 independent microarrays in HCC patients

| Cancer vs. Normal | Array type | P-value | Fold Change | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mas Liver | RNA | 0.012 | 3.324 | n=115 |

| Guichard Liver cohort 2 | DNA | 0.036 | 2.025 | n=52 |

| TCGA Liver | DNA | 0.003 | 2.063 | n=212 |

| Guichard Liver cohort 1 | DNA | 0.026 | 2.153 | n=185 |

CCL2 expression in human clinical samples (Cancer VS. Normal). Data provided by Oncomine (www.oncomine.com, January 2016, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ann Arbor, MI). TCGA database (TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov) contain >200 HCC specimens of different etiology (HBV, HCV, alcohol, and NAFLD). Mas liver, is a RNA array which contains >100 HCC samples (mostly HCV positive) (20). The Guichard liver DNA array consisting of 237 HCCs of various risk factors including HBV, HCV, alcohol, and NAFLD, was analyzed by exosome sequencing and SNP array (19).

Fig.1. CCL2 is overexpressed in human cirrhotic livers, as well as cirrhotic and noncirrhotic HCCs.

CCL2 RNA expression retrieved from GEO data (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession_GSE14323 (20) was compared among the four types of liver tissues and statistical analysis was done using ANOVA.

CCL2-CCR2 blockade reduced chronic inflammation and liver injuries in miR-122 KO mice

CCL2 is a major chemokine that is known to cause various inflammatory diseases in humans (10, 21). Similarly, upregulation of CCL2 in miR-122 knockout (KO) liver correlated with chronic inflammation (8). To determine whether CCL2 is a key player in hepatitis, and blocking CCL2 could inhibit liver inflammation, CCL2 neutralizing antibody (nab) was administered to 4-month-old miR-122 KO mice by intraperitoneal injection for 4 weeks (Fig. 2A). CCL2 nab (C1142) displayed certain specificity toward murine CCL2 (14). In addition, CCL2 nab was well tolerated in mice (14). Furthermore, its anti-tumor efficacy has been demonstrated in murine breast cancer metastasis (22), lung (23), brain (24), and prostate cancer (25, 26) models and no adverse effects were reported.

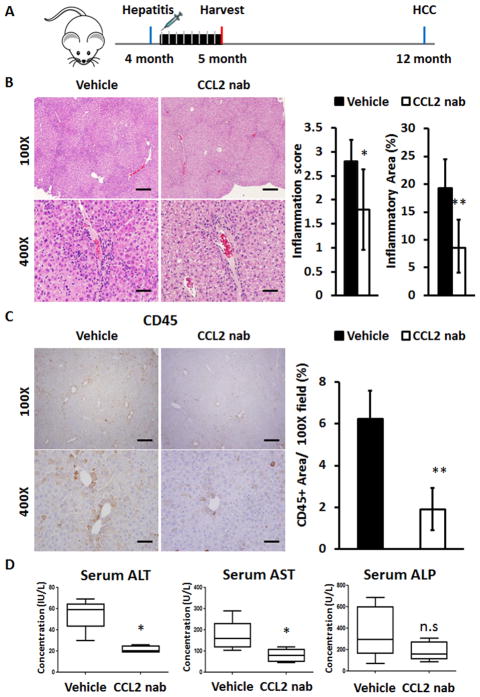

Fig. 2. CCL2 neutralizing antibody therapy reduces chronic liver inflammation and liver damage in adult miR-122 KO mice.

(A) The schematic presentation of the Ccl2 nab treatment. (B) Liver histology of 4-month-old male KO mice injected IP with Ccl2 nab (2mg/kg, n=5) or PBS (vehicle, n=5). Representative images of H&E stained liver sections (top panel scale bar: 100μm, lower panel: 25μm). Right panel is the quantitation of the inflammation scores generated through blinded evaluation of H&E stained liver sections (x100 magnification, 100μm). The inflammatory area was quantified by imageJ of 3 randomly chosen fields (x 100 magnification, 100um) per animal (n=5). (C) Representative images of CD45 stained liver sections (top panel scale bar: 100μm, lower panel: 25μm). Right panel represents the CD45+ areas quantified by imageJ of 3 randomly chosen fields (x 100 magnification, 100um) per animal (n=5). (D) Analysis of serum ALT, AST and AFP levels (n=5).

To evaluate the effects of CCL2 nab in suppressing hepatitis, we treated 4-month-old miR-122 KO mice with CCL2 nab followed by histopathological and serological analyses. As reported in other mouse models (14, 22–26), CCL2 nab is well tolerated in miR-122 KO mice. There were no obvious changes in the in appearance, activity or body weight (Supplementary Fig. 1). Liver histology showed reduced immune cell infiltration after treating with CCL2 nab (Fig. 2B). Similarly, CD45 immunohistochemical analysis revealed that CCL2 nab treatment decreased leukocyte accumulation in the liver (Fig. 2C). Notably, a significant reduction in serum ALT and AST levels corroborated that the liver damage due to hepatitis in KO mice could be reversed by inhibition of CCL2 (Fig. 2D). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), a marker of biliary dysfunction, was also reduced by ~50%; however, it was not statistically significant (Fig. 2D). This result implies that blocking CCL2 may not be able to fully rescue hepatobiliary damage because ALP is a target of miR-122 which is de-repressed in miR-122 depleted livers (8, 9). Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and bilirubin (total and direct) levels were not significantly altered in CCL2 nab injected mice (Supplementary Table 2).

We have shown that activation of the CCL2-CCR2 axis in miR-122 KO liver correlates with the recruitment of CD11bhighGr1+ cells and hepatic inflammation and injuries (8). Additionally, CCR2 inhibitors showed anti-inflammatory effects in the animal models with different diseases such as diabetic nephropathy (27), kidney hypertension (28), steatohepatitis (29), renal atrophy (30) models and no adverse effects were reported. We decided to test whether treatment of mice with a CCR2-specific inhibitor could reduce liver inflammation in KO mice. Indeed, KO mice fed water containing a CCR2 inhibitor exhibited reduced hepatic inflammation, as revealed by the dramatic reduction in bridging inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Collectively, these data showed that blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis could effectively inhibit hepatitis in miR-122 KO mice.

CCL2 nab therapy inhibited hepatitis by reducing CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells accumulation

It is well established that immune cells play a critical role in liver inflammation (31). Our previous study showed that CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells excessively accumulated in miR-122 depleted livers (8). Additionally, CD11bhighGr1+ cells, which express CCR2 (8) are known to be recruited to the liver via CCL2-CCR2 interaction (32). Therefore, we quantitated CD11bhighGr1+ cells in KO livers depleted of CCL2 or CCR2. Flow cytometric analysis of the immune cells isolated from livers and spleen showed reduced CD11bhighGr1+ cell population in the KO mice treated with CCL2 nab without significant change in their numbers in peripheral blood (Fig. 3A, 3B and Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with other studies (12, 13), we also found decreased number of hepatic macrophages in liver by IHC upon blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, no significant alterations in the number of hepatic B, T and Natural killer (NK) cells were observed (Supplementary Fig. 5A-D). Additionally, Immune cells isolated from CCR2 inhibitor treated KO mice showed reduced hepatic CD11bhighGr1+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 6), further supports the idea that blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis reduces CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells in liver.

Fig. 3. CCL2 nab treatment decreases liver CD11bhighGr1+ cell population and IL-6 & TNF-α expression in adult KO mice.

(A) Injection of 4 months old KO mice Ccl2 nab reduced the hepatic CD11bhighGr1+ population. Right panel is the quantitation of hepatic CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells (n=5). (B) Reduced CD11bhighGr1+ population in spleen. Right panel is the quantitation of splenic CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells (n=5). (C) RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

IL-6 and TNF-α are two pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive hepatitis and HCC in the liver (33). Previously, we have shown that CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells produce IL-6 and TNF-α in the miR-122 KO liver (8). Therefore, it is expected that hepatic IL-6 and TNF-α levels would be suppressed if the population of CD11bhighGr1+ cells is decreased in the CCL2 nab treated mice. Indeed, the expressions of both cytokines were reduced in the livers of CCL2 nab treated group (Fig. 3C). In addition, we also observed a decrease in Il-1β expression upon CCL2 nab treatment (Fig. 3C). Notably, CCL2 nab treatment did not altered the expressions of other inflammatory cytokines or chemokines such as Ccl5, Ccl8, Cxcl9, Il-10, Ccl2 or Ccr2 (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that inhibition of the CCL2-CCR2 axis reduces liver inflammation by suppressing CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells, which leads suppression of the two major pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α.

Attenuation of hepatocarcinogenesis in miR-122 KO mice treated with CCL2 nab

As aforementioned, CCL2 is highly expressed in the tumor tissues of HCC patients (Fig. 1, Table1). Besides, blocking CCL2 suppresses chronic liver inflammation at early stages of HCC development in the KO mice (Fig. 2). Therefore, we speculated that impeding CCL2 function would suppress development of spontaneous liver tumors in KO mice. To test this, male KO mice (~12 months old) bearing liver tumors confirmed by the serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, were randomly assigned to two treatment groups. Comparison of the serum AFP level with the tumor size in a large number of KO mice revealed that mice with serum AFP levels >12 IU/ml usually developed tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7A). This ELISA data was further confirmed by the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 4A). KO mice were injected ip with CCL2 nab (2mg/Kg) or vehicle twice a week for 8 weeks (Fig. 4A) and analyzed the tumor burden one week after the last injection. We chose male KO mice for this study as these mice, like men, have higher HCC penetrance and tumor burden (8, 9).

Fig. 4. Blocking CCL2 function suppresses HCC development in KO mice.

(A) The schematic depiction of the immunotherapy protocol and the representative magnetic resonance images (MRI) of liver tumors (axial view, T1 weighted) for 12-month-old miR-122 KO mice. (B) Five representative images of the livers harvested from the vehicle (n=9) and CCL2 nab treated mice (n=11). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of hepatic CD11bhighGr1+ immune cells in the vehicle and CCL2 nab treated mice. (D) Representative images of liver histology, AFP and GPC3 immunohistochemical images of the vehicle and nab treated groups (scale bar: top: 250μm, middle: 100μm, bottom: 25μm).

Significant phenotypic differences were observed in the liver between the vehicle- and the CCL2 nab- treated groups after 8 weeks of CCL2 immunotherapy; however, there were no obvious changes in the appearance, activity or body weight between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 7B). While the majority of the PBS-injected mice developed large macroscopic liver tumors, CCL2 nab treated mice mostly developed smaller and fewer tumors (Fig. 4B, Table 2). Consistent with the previous data (Fig. 3A), we found hepatic CD11bhighGr1+ cell population was reduced in the CCL2 nab treated tumor-bearing mice compared to vehicle-treated group (Fig. 4C). In addition, serum AFP and ALT levels were lower in the CCL2 nab treated mice (Table 2). Furthermore, the majority of the HCCs in the vehicle-treated group were AFP and Glypican 3 (GPC3) positive, and grade 2–3 (intermediate to poorly differentiated) HCCs whereas those in CCL2 inactivated mice were mostly grade 1 (well differentiated) HCCs, AFP and GPC3 negative (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that CCL2 blockade is not only anti-inflammatory but also anti-tumorigenic in the liver.

Table 2.

Histopathological and serological analysis of tumor-bearing miR-122 KO mice treated with CCL2 nab for 8 weeks.

| Vehicle | Ccl2 nab | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCC incidence | 8/9 | 5/11 | 0.07 |

| Tumor number | 2.67± 1.22 | 0.73± 0.79 | 0.0004 |

| Sum of tumor diameter (cm) | 1.71± 1.24 | 0.57± 0.65 | 0.01 |

| Serum ALT (U/L) | 151.89± 68.06 | 73.57± 28.5 | 0.027 |

| Serum AFP (IU/ml) | 14.07± 3.51 | 9.95± 0.61 | 0.001 |

All measurements are presented as mean ± SD. P-values were calculated using student’s 2-tailed t-test (for tumor number, sum of tumor diameter, tumor weight, ALT, and AFP) or Fisher’s exact test (for HCC incidence).

Oncogenic signaling downstream of IL-6 and TNF-α was blocked in miR-122 KO tumors upon CCL2 nab therapy

Because CCL2 nab treatment suppressed the level of IL-6 and TNF-α in liver (Fig. 3C), we hypothesized that the downstream oncogenic signaling pathways of IL-6 and TNF-α, namely STAT3 and NF-κB, respectively, would be inhibited in the CCL2 depleted mice. Indeed, immunoblot analyses showed that phospho-STAT3 (Y705) level was dramatically reduced while total-STAT3 level decreased only slightly in the tumors of CCL2 nab treated mice (Fig. 5A, C). Reduced nuclear STAT3 levels in the CCL2 nab treated mice confirmed that CCL2 inhibition suppresses STAT3 functions in liver tumors (Fig. 5B, C). Similarly, the level of two major NF-κB subunits, p65, and p50, was reduced in both whole liver lysates and nuclear extracts (Fig. 5B, C). The level of c-MYC, a downstream target of STAT3, was also reduced in the CCL2 nab treated mice (Fig. 5A, C). Histologically, p65 and c-MYC both showed reduced expression in the transformed hepatocytes while pSTAT3 was decreased in immune cells as well as tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 5. CCL2 nab therapy suppresses HCC development in KO mice by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation.

(A) Immunoblotting of the key downstream proteins of IL-6 and TNF-α in KO tumors. (B) Immunoblotting of NK-κB subunit and STAT3 in the tumor nuclear extracts. (C) Respective protein levels were normalized to those of GAPDH or KU86. Quantitation was done by ImageJ. (D) Representative images of Ki-67 staining (scale bar: 100μm, inset: 25μm). Quantitation was done by ImageJ of 3 randomly chosen fields (x 200 magnification, 50μm) per animal (n=5). (E) Immunoblotting of PCNA in liver tumors.

c-MYC is a well-known oncogene that promotes HCC proliferation (34, 35). Therefore, Ki-67 expression, a marker of cell proliferation, was evaluated in tumor cells by immunohistochemistry. As expected, the number of Ki-67 positive cells was much less in both CCL2 depleted tumor and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. 9). PCNA, another cellular proliferation marker, was also reduced in the CCL2 nab-treated tumor extracts (Fig. 5E). Of note, we found cell apoptosis is increased in the CCL2 nab treated group as demonstrated by slight increase in cleaved PARP and cleaved Caspase-7 levels (Supplementary Fig. 10). These data suggests that inhibition of HCC growth by targeting CCL2 is, at least in part, through the inhibition of STAT3 and NF-κB signaling and c-MYC expression.

CCL2 nab activated nature killer (NK) cells in the tumor microenvironment to suppress liver cancer

Cancer immunotherapy has been widely conducted in the clinic over the past several years (36–38). Since antibody-based immunotherapy is applied in this study, and NK cell is known to be activated by the Fc domain of antibodies (37), we investigated whether enhanced NK cytotoxicity could be a mechanism of tumor suppression in CCL2 nab-treated mice. Although the total number of NK cells did not change significantly after CCL2 nab immunotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D), the activity of NK cells increased, as demonstrated by the upregulation of hepatic Ifn-γ expression (Fig. 6A). To verify the source of the elevated IFN-γ, primary hepatic immune cells isolated from tumor-bearing KO mice were co-cultured with mouse hepatoma (Hepa1–6) cells in the presence of CCL2 nab. The culture supernatants were subjected to IFN-γ ELISA and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Both ELISA and intracellular staining data showed that only NK cells (Fig. 6B, C) were the major producers of IFN-γ. Additionally, the cell surface expression of CD69, a marker for activated NK cells, increased when NK cells were co-cultured with CCL2 nab treated mouse hepatoma (Hepa) cells (Fig. 6D), suggesting that NK cells could be activated upon exposure of hepatoma cells to CCL2 nab. To confirm the activated NK cells could suppress cancer cell growth, NK cell cytotoxicity was assessed by Chromium-51 (Cr-51) release assay (16, 39). To this end, Hepa cells were first labeled with Cr-51 followed by incubation with CCL2 nab and subsequently, with tumor-derived NK cells. Enhanced release of Cr-51 from hepa cells is indicative of higher cytotoxicity of NK cells. Indeed, tumor-derived NK cells co-cultured with Hepa cells and CCL2 nab exhibited higher cytotoxicity (Fig. 6E). This result also suggested that the increased cytotoxicity of NK cells could be triggered independent of other immune cells. Collectively, these results demonstrate that CCL2 nab impedes tumor growth, at least in part, by activating NK cells.

Fig. 6. CCL2 nab activates NK cells in KO mouse livers.

(A) RT-qPCR analysis of hepatic Ifn-γ in CCL2 nab treated mice. (B) IFN-γ quantification by ELISA in the supernatants of cultured Hepa and hepatic immune cells. (C) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ in the co-cultured immune cells. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of the activated NK cell surface marker, CD69. (E) Cytotoxicity of hepatic NK cells towards CCL2 nab treated Hepa cells

Discussion

CCL2 is a chemotactic factor to tumor cells and inflammatory macrophage/ monocytes. Blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis by CCR2 inhibitor decreases the intrahepatic macrophage infiltration in a diet induced steatohepatitis model (29). CCL2 Spiegelmer, a CCL2 RNA antagonist, suppresses the macrophage infiltration in the carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and methionine–choline-deficient (MCD) diet-induced liver injury models (12). Recently, Li et al. also demonstrated the importance of CCL2-CCR2 axis in different HCC models (13). In line with the animal models mentioned above, it is clear that CCL2 is crucial for regulating the inflammatory milieu in liver. In the present study, we aimed at elucidating the efficacy of CCL2 immunotherapy against chronic hepatitis and HCC in a murine model. This is a logical extension of our previous study that demonstrated a causal role of CCL2 in the inflamed liver that progressively leads to HCC in miR-122 KO mice (8). Analysis of GEO, Oncomine™ and Protein Atlas databases showed increased CCL2 expression in patients suffering from HCC (18, 20, 40). These data suggest CCL2 may play a role in liver cancer. To further clarify the role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis in chronic liver inflammation and tumor development, we used CCL2 nab to block CCL2 signaling. Our data suggest that CCL2 nab inhibits tumor development in miR-122 KO mice through at least two distinct mechanisms: suppressing IL-6 and TNF-α production by reducing the infiltration of CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells to the liver and enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity (Supplementary Fig. 11).

An elegant study demonstrating the correlation of CCL2 protein level with poor survival of HCC patients was published (13) during the preparation of our manuscript. Li et al. showed that a clinically relevant CCR2 antagonist inhibited murine HCC progression by reducing M2-type tumor-associated macrophage population and increasing CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in orthotopic and subcutaneous HCC models (13). Their study supports the notion that blocking the CCL2-CCR2 axis has profound effects in modulating liver immune system to suppress HCC progression. While Li et al. found macrophage and CD8+ T cells are regulated by a CCR2 inhibitor in xenograft models, we found CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells and NK cells could be modulated by CCL2 nab in miR-122 KO mouse livers. Thus, these studies (ours and Li et al.) demonstrated that targeting CCL2-CCR2 axis by blocking the receptor or the ligand could be effective HCC therapy. In future, it would be interesting to investigate whether combination of both would be more effective. Furthermore, we used our unique animal model to study the role of CCL2 in liver inflammation and HCC progression in the light of our previous work (8). We demonstrated two different types of immune cells including CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells and NK cells play key roles in regulating liver inflammation and tumor development after blocking CCL2 function. In addition, CD11bhighGr1+ inflammatory myeloid cells promote tumorigenesis by increasing tumor cell proliferation via IL-6 and TNF-α. Both IL-6 and TNF-α are well-known pro-inflammatory cytokines that activate oncogenic transcription factor STAT3 to promote HCC development (33, 41). Consistent with the previous findings, our present data reveal that CCL2 nab reduces accumulation of CD11bhighGr1+ cells, which decreases IL-6 and TNF–α levels in the tumor and surrounding liver tissues, and reduces the activation of STAT3 and the expression of c-MYC. Ours and Li et al. data demonstrated that targeting the CCL2-CCR2 axis by blocking the receptor or the ligand could be an effective HCC therapy. In future, it would be interesting to investigate whether combination of both would be a more effective therapeutic approach.

NK cells are key modulators of liver diseases. Activated NK cells suppress liver disease progression from chronic hepatitis to HCC (42). Based on ours and Li et al. data (13), CCL2 is expressed in liver tumors of both mouse and human origin. The CCL2 nab binds to Fc receptor (CD16) on NK cells (37), and the CCL2 secreted from tumor cells binds to the CCL2 nab. This can trigger NK cell activation (i.e., enhancement of IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity), causing enhanced killing of liver tumor cells. In this study, we observed enhanced cytotoxic capability of NK cells against CCL2 nab-treated hepatoma cells. We also noticed that the level of IFN-γ was higher in the NK cells isolated from livers of tumor-bearing KO mice treated with CCL2 nab, reinforcing the notion that NK cells were activated by the CCL2 nab. Consistent with other literatures that cytotoxic NK cells activate Caspase 3, 7 and PARP (43, 44), we found increased cleaved-Caspase-7 and cleaved-PARP in the CCL2 nab treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 10). Inhibition of STAT3 activity has been shown to sensitize HCC cells to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity (45). Interestingly, our data show that STAT3 activity is reduced in the CCL2 nab treated mice tumors (Fig. 5A–C), suggesting a reciprocal regulation.

Novel therapeutic strategies for HCC are urgently needed since existing therapies could not cure or prolong patients’ survival even by 6 months (5). In this study, we highlight the importance of CCL2 in contributing to chronic liver inflammation and tumorigenesis. Furthermore, the efficacy of a CCL2 specific neutralizing antibody in the miR-122 mouse model underscores the feasibility of immune-based therapy in inflammatory liver disease and cancer. Our study shows that CCL2 nab immunotherapy elicits two distinct mechanisms that act in concert to inhibit hepatitis and HCC development, and provides rationales for future clinical trials in HCC patients with chronic inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Comparative Pathology and Mouse Phenotyping core for pathological analysis. We thank Dr. Gretchen Darlington (Baylor College of Medicine) for providing Hepa1-6 cells, Dr. Huban Kutay for breeding miR-122 KO mice and Vivek Chowdhary, Ryan Reyes, and Dr. Hui-Lung Sun for the valuable discussions. This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants R01CA193244 (K. Ghoshal) and R01CA086978 (S. T. Jacob and K. Ghoshal) as well as by Pelotonia IDEA grants (J. Yu and K. Ghoshal) and Pelotonia Graduate Fellowship (K-Y. Teng).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, Finn RS. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2015;12:408–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marquardt JU, Andersen JB, Thorgeirsson SS. Functional and genetic deconstruction of the cellular origin in liver cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2015;15:653–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nature reviews Cancer. 2006;6:674–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:1344–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakral S, Ghoshal K. miR-122 is a unique molecule with great potential in diagnosis, prognosis of liver disease, and therapy both as miRNA mimic and antimir. Current gene therapy. 2015;15:142–50. doi: 10.2174/1566523214666141224095610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu SH, Wang B, Kota J, Yu J, Costinean S, Kutay H, et al. Essential metabolic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumorigenic functions of miR-122 in liver. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2871–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI63539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai WC, Hsu SD, Hsu CS, Lai TC, Chen SJ, Shen R, et al. MicroRNA-122 plays a critical role in liver homeostasis and hepatocarcinogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2884–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI63455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonelli A, Fallahi P, Delle Sedie A, Ferrari SM, Maccheroni M, Bombardieri S, et al. High values of Th1 (CXCL10) and Th2 (CCL2) chemokines in patients with psoriatic arthtritis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2009;27:22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia M, Sui Z. Recent developments in CCR2 antagonists. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2009;19:295–303. doi: 10.1517/13543770902755129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeck C, Wehr A, Karlmark KR, Heymann F, Vucur M, Gassler N, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) diminishes liver macrophage infiltration and steatohepatitis in chronic hepatic injury. Gut. 2012;61:416–26. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Yao W, Yuan Y, Chen P, Li B, Li J, et al. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsui P, Das A, Whitaker B, Tornetta M, Stowell N, Kesavan P, et al. Generation, characterization and biological activity of CCL2 (MCP-1/JE) and CCL12 (MCP-5) specific antibodies. Human antibodies. 2007;16:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu J, Mitsui T, Wei M, Mao H, Butchar JP, Shah MV, et al. NKp46 identifies an NKT cell subset susceptible to leukemic transformation in mouse and human. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:1456–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI43242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunner KT, Mauel J, Cerottini JC, Chapuis B. Quantitative assay of the lytic action of immune lymphoid cells on 51-Cr-labelled allogeneic target cells in vitro; inhibition by isoantibody and by drugs. Immunology. 1968;14:181–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majumder S, Roy S, Kaffenberger T, Wang B, Costinean S, Frankel W, et al. Loss of metallothionein predisposes mice to diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis by activating NF-kappaB target genes. Cancer research. 2010;70:10265–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 2007;9:166–80. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, Ladeiro Y, Pelletier L, Maad IB, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature genetics. 2012;44:694–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mas VR, Maluf DG, Archer KJ, Yanek K, Kong X, Kulik L, et al. Genes involved in viral carcinogenesis and tumor initiation in hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass) 2009;15:85–94. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2008.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankovic A, Slavic V, Stamenkovic B, Kamenov B, Bojanovic M, Mitrovic DR. Serum and synovial fluid concentrations of CCL2 (MCP-1) chemokine in patients suffering rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis reflect disease activity. Bratislavske lekarske listy. 2009;110:641–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fridlender ZG, Kapoor V, Buchlis G, Cheng G, Sun J, Wang LC, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 blockade inhibits lung cancer tumor growth by altering macrophage phenotype and activating CD8+ cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2011;44:230–7. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, Fujita M, Snyder LA, Okada H. Systemic delivery of neutralizing antibody targeting CCL2 for glioma therapy. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2011;104:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loberg RD, Ying C, Craig M, Yan L, Snyder LA, Pienta KJ. CCL2 as an important mediator of prostate cancer growth in vivo through the regulation of macrophage infiltration. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 2007;9:556–62. doi: 10.1593/neo.07307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loberg RD, Ying C, Craig M, Day LL, Sargent E, Neeley C, et al. Targeting CCL2 with systemic delivery of neutralizing antibodies induces prostate cancer tumor regression in vivo. Cancer research. 2007;67:9417–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seok SJ, Lee ES, Kim GT, Hyun M, Lee JH, Chen S, et al. Blockade of CCL2/CCR2 signalling ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28:1700–10. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Olearczyk JJ, Sridhar A, Cook AK, Inscho EW, et al. Chemokine receptor 2b inhibition provides renal protection in angiotensin II - salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:1069–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302:G1310–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00365.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashyap S, Warner GM, Hartono SP, Boyilla R, Knudsen BE, Zubair AS, et al. Blockade of CCR2 reduces macrophage influx and development of chronic renal damage in murine renovascular hypertension. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2016;310:F372–84. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00131.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao L, Lim SY, Gordon-Weeks AN, Tapmeier TT, Im JH, Cao Y, et al. Recruitment of a myeloid cell subset (CD11b/Gr1 mid) via CCL2/CCR2 promotes the development of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2013;57:829–39. doi: 10.1002/hep.26094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell. 2010;140:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui L, Zatloukal K, Scheuch H, Stepniak E, Wagner EF. Proliferation of human HCC cells and chemically induced mouse liver cancers requires JNK1-dependent p21 downregulation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3943–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI37156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawate S, Fukusato T, Ohwada S, Watanuki A, Morishita Y. Amplification of c-myc in hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with clinicopathologic features, proliferative activity and p53 overexpression. Oncology. 1999;57:157–63. doi: 10.1159/000012024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.June CH. Adoptive T cell therapy for cancer in the clinic. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:1466–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI32446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiner GJ. Building better monoclonal antibody-based therapeutics. Nature reviews Cancer. 2015;15:361–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015;12:681–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trotta R, Dal Col J, Yu J, Ciarlariello D, Thomas B, Zhang X, et al. TGF-beta utilizes SMAD3 to inhibit CD16-mediated IFN-gamma production and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in human NK cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2008;181:3784–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science (New York, NY) 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toffanin S, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Obesity, inflammatory signaling, and hepatocellular carcinoma-an enlarging link. Cancer cell. 2010;17:115–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian Z, Chen Y, Gao B. Natural killer cells in liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2013;57:1654–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.26115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saini RV, Wilson C, Finn MW, Wang T, Krensky AM, Clayberger C. Granulysin delivered by cytotoxic cells damages endoplasmic reticulum and activates caspase-7 in target cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2011;186:3497–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warren HS, Smyth MJ. NK cells and apoptosis. Immunology and cell biology. 1999;77:64–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sui Q, Zhang J, Sun X, Zhang C, Han Q, Tian Z. NK cells are the crucial antitumor mediators when STAT3-mediated immunosuppression is blocked in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2014;193:2016–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.