Abstract

Background

Social anxiety is one of the most common psychological disorders that exists among children and adolescents, and it has profound effects on their psychological states and academic achievements.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on diminishing social anxiety disorder symptoms and improving the self-esteem of female adolescents suffering from social anxiety.

Patients and Methods

Semi-experimental research was conducted on 30 female students diagnosed with social anxiety. From the population of female students who were studying in Tehran’s high schools in the academic year of 2013 - 2014, 30 students fulfilling the DSM-5 criteria were selected using the convenience sampling method and were randomly assigned to control and experimental groups. The experimental group received eight sessions of MBCT treatment. The control group received no treatment. All participants completed the social phobia inventory (SPIN) and Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) twice as pre- and post-treatment tests.

Results

The results from the experimental group indicated a statistically reliable difference between the mean scores from SPIN (t (11) = 5.246, P = 0.000) and RSES (t (11) = -2.326, P = 0.040) pre-treatment and post-treatment. On the other hand, the results of the control group failed to reveal a statistically reliable difference between the mean scores from SPIN (t (12) = 1.089, P = 0.297) and RSES pre-treatment and post-treatment (t (12) = 1.089, P = 0.000).

Conclusions

The results indicate that MBCT is effective on both the improvement of self-esteem and the decrease of social anxiety. The results are in accordance with prior studies performed on adolescents.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Cognitive Therapy, Phobic Disorders, Self-Esteem, Female

1. Background

Anxiety disorder is one of the most common clinical problems in children and adolescents (1). More specifically, social anxiety disorder is the fourth common psychological disorder, and its lifetime prevalence is 9.5% in females and 4.9% in males; the six-month prevalence rate is about 2% - 3%, and among high-school adolescents. This rate increases to 5% - 10%. Children and adolescents diagnosed with social anxiety are prone to academic problems, drug abuse, long periods of disability, and considerable pathologies in their daily lives and social relationships (2-4).

There are several types of effective therapies for social phobia disorder, including behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive behavioral group therapy (CBGT), pharmacotherapy, and instruction of social skills (2). Currently, the main focus in the treatment of social phobia disorder is on CBT. Although it has been shown to have relatively successful results, there still remain three problems: first, it requires a long period of treatment; second, the need for a high level of expertise is required in order to implement it effectively; and third, it generally has lower-than-expected effectiveness (5). Thus, it is necessary to look for interventions in the treatment of this disorder that are shorter in time, simpler to implement, and less irritating in that they do not need a very high level of expertise (6).

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy or MBCT (7), a derivative of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (8) and classical cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), is a highly economic intervention designed to prevent depressive relapse. In MBCT, patients practice various forms of mindfulness meditation in a group setting and learn to apply these techniques in their daily lives. The core elements of MBCT involve refining attention skills and cultivating mindfulness, i.e. the skill of attentively and intentionally relating to the experience of the present moment in a non-judgmental manner (8). In turn, patients become more aware of their physical sensations and feelings, and can identify potentially harmful thought patterns before they become a threat. The treatment is closely based on an approach that is known to be helpful in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Since MBCT improves mood and its short-term implementation decreases fatigue and anxiety (9), and considering its effects on depression (10), anxiety, and psychological adaptability (11), it is somewhat surprising that few studies whether in Iran or other countries have addressed the effect of this therapy on social phobia symptoms. Therefore, further examinations of the effectiveness of this new therapeutic model on social anxiety and its ability to improve variables such as self-esteem are necessary.

2. Objectives

The current study was designed to examine the effectiveness of MBCT on decreases in social anxiety and increases in self-esteem of Iranian female adolescents suffering from social anxiety.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Trial Design and Sampling

This research was conducted as a semi-experimental clinical trial with experimental and control groups. Three government schools were chosen for more convenient sampling, two of which refused participation. In May of 2013, Farhang 13th High School, which is a government organization, gave their permission for us to conduct our study on their students. 137 students were assessed for eligibility based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I (SCID-I), and 35 students were chosen from this group. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. According to the exclusion criteria, five students were omitted due to their history of psycho-medication and general unwillingness to participate. Then, 30 students in four classes (two classes from the 7th grade and two classes from 8th grade) were assigned randomly to experimental and control groups, each group containing members from one 7th grade class and members from one 8th grade class.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Having the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria ( 12 ) | Receiving pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy |

| Having an age ranging between 12 - 18 | Having psychosis or schizophrenia |

| Score of +16 on the Social Phobia Questionnaire | Having other personality disorders |

| Willingness to participate and signed consent form | Unwillingness to participate |

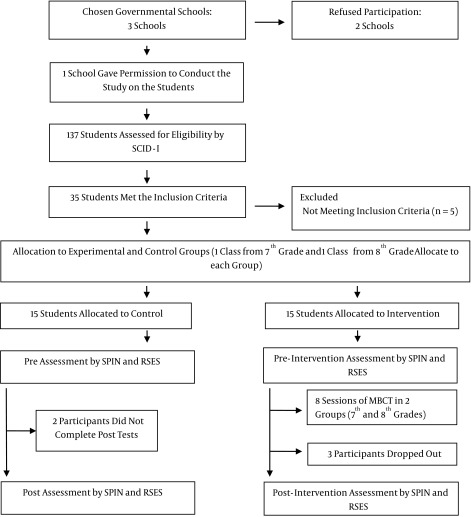

The social phobia inventory (SPIN) and Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale were used in the pre-test process. Both groups completed the pre-test. Then, group sessions of MBCT were held separately for both classes of the experimental group, including eight sessions of 1.5 hours once a week, and the control group did not attend any sessions. The sessions were held in the consulting room of Farhang 13th high school in Tehran in November and December of 2013. After the end of the training sessions (two month later), both groups completed the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) and Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale again as post-tests. During the therapeutic sessions, three members of the experimental group dropped out, and later, two members of the control group did not complete the post-test; as a result, the data analysis was ultimately carried out on 25 participants (12 in the experimental group and 13 in the control group) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram of Participants.

All female adolescents diagnosed with social phobia disorder studying in the high schools of Tehran in the academic year of 2013 - 14 formed the target research population. Convenience sampling based on random assignment was used in this study. The selected sample was divided into two groups in such a way that 15 persons were assigned to each group. All participants were female, with the mean age of 14.8 for the experimental group, and 15.1 for the control group. The mean age of the parents was 42.3 and 44.6 for the experimental and control groups, respectively. All families were from the middle socioeconomic class.

The desired size of the sample was 34 (17 in each group), based on a level of significance of (α) = 5%, β = 20% (power = 80%), and the following formula:

| Equation 1. |

Despite our efforts to fulfill the desired sample size, it could not be met due to barriers that existed within schools and limitations imposed by school principals. Thus, we tried to make up for this limitation by choosing samples precisely in accordance with the DSM-5 criteria for social phobia.

3.2. Ethical Considerations

All participants were asked to sign a consent form. However, before signing the form, the students were provided with a general overview of the aims and characteristics of the study. They were also informed that their participation was voluntarily and that they could choose to withdraw at any time. The results were used anonymously and all of the personal details of the data were kept secret in this study. The current article has been extracted from the thesis of the first author which was written for the M.Sc. degree from Tabriz University. The clinical trial was approved by the ethics committee of the departments of psychology and educational sciences of Tabriz university in April of 2013, and all of the interventions were supervised by two assistant professors from the university. The study also followed all of the ethical principles for human subjects stipulated in the declaration of Helsinki (13).

3.3. Questionnaires

3.3.1. Demographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by the current researchers and was used to collect demographic information about the participants. The collected information included age, financial status, and education level.

3.3.2. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I (SCID-I)

The SCID is a structured interview developed by First, Spitzer, Gibbon, and Williams (14). It is a comprehensive and standardized instrument for assessing major mental disorders in clinical and research atmospheres, administrated in a single session and taking about 45 to 90 minutes to complete (14). The inter-rater diagnostic reliability with Kappa is higher than 0.7 in most diagnoses (14). The Persian version of this questionnaire has been provided by Sharifi et al. (15). The validity of the questionnaire as an instrument for assessment has been confirmed by clinical psychologists and its retest reliability was determined to be 0.95 over one week (15).

3.3.3. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)

This questionnaire was first developed by Connor et al. in order to assess social anxiety or social phobia (16). This inventory is a self-assessment scale with 17 items including three subscales of phobia (6 items), avoidance (7 items), and physiological distress (4 items). Each item is scaled using a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely). With regard to the psychometric properties of this questionnaire, its test-retest reliability in the groups diagnosed with social phobia disorder was equal to the correlation coefficient and calculated to be 0.78 to 0.89. The internal consistency of the alpha coefficient in the group of normal individuals was 0.94 for the whole scale and 0.80 for the physiological subscales. A cut-off point of 19 with an efficiency of 0.79 discriminates between those who are suffering from social phobia disorder and those who are not; a cut-off point of 15 with an efficiency of 0.78 discriminates between the participants diagnosed with social phobia disorder and the participants in the control group; finally, a cut-off point of 16 with an efficiency of 0.80 discriminates between those with social phobia disorder and those in the control group without social phobia disorder (16). In Iran, Momeni (17) reported that Cronbach's alpha of the whole questionnaire was 0.88 and 0.77 and the correlation between the two halves was 0.77; the reliability of the coefficient was calculated using the Spearman-Brown test and determined to be 0.87.

3.3.4. Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

The purpose of the 10-item RSE scale is to measure self-esteem. Originally, the scale was designed to assess the self-esteem of high school students. However, since its development, the scale has been used with a wider variety of groups including adults. As the RSES is a Guttman scale, scoring can be a little complicated. Scoring involves a method of combined ratings. Low self-esteem responses include disagree or strongly disagree on items 1, 3, 4, 7, and 10, and strongly agree or agree on items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Two or three out of three correct responses (indicating low self-esteem) to items 3, 7, and 9 are scored as one item. One or two out of two correct responses for items 4 and 5 are considered as a single item; items 1, 8, and 10 are scored as individual items; and combined correct responses (one or two out of two) to items 2 and 6 are considered to be a single item. The scale can also be scored by totaling the individual 4-point items after reverse-scoring of the negatively worded items (18).

The RSES demonstrates a Guttman scale coefficient of reproducibility of .92, indicating excellent internal consistency. Test-retest reliability over a period of two weeks reveals correlations of .85 and .88, indicating excellent stability. The RSES correlates significantly with other measures of self-esteem, including the Coopersmith self-esteem inventory. In addition, the RSES correlates in the predicted direction with measurements of depression and anxiety (18).

The RSES has been translated into 28 languages and administered to 16,998 participants across 53 nations. The RSES structure is largely invariant across nations. RSES scores correlated with neuroticism, extraversion, and styles of romantic attachment are similar among nearly all nations, providing additional support for the cross-cultural applicability of the RSES. All nations scored above the theoretical midpoint of the RSES, indicating that generally positive self-evaluation may be culturally universal (19). In Iran, the test-retest correlation coefficients with time intervals of two weeks, five months, and one year were reported to be 0.84, 0.86, and 0.62, respectively (20).

3.4. Intervention

3.4.1. Brief Manual for the Use of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

MBCT participants were entered into the study only if they had not received any other form of individual psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy at the time, and they were asked not to start any alternative method of therapy during the period of the study.

Before the start of the treatment phase, participants in the MBCT group were invited for a pre-class interview with the therapist to prepare them for the course. The MBCT treatment followed the manual written by Segal et al. (7). Handouts and protocol sheets for home practice were reproduced and distributed from the manual without major alteration. Participants in the MBCT category met in a group of, initially, 15 patients for eight weekly two-hour classes in June and July of 2013. In addition to the classes, they were asked to engage in homework including regular meditation or mindful movement practice and various other related exercises for about an hour per day for six days a week. The classes were led by a fully-qualified CBT therapist who had been trained in mindfulness-based stress reduction (21).

3.4.2. Agenda of MBCT Sessions

The session before the beginning of treatment: In this session, participants were examined in terms of the DSM-IV-TR social phobia discriminative criteria, the therapy was introduced, participants became familiarized with the process and structure of this therapy, and the necessity of doing the assignments was emphasized. Then, their questions and concerns about the therapy were answered. Thus, the participants were deemed to be mentally prepared to begin the therapy. First session: Patients became familiar with MBCT, social phobia disorder, automatic guidance, fear of being evaluated by others, and the cognitive issues of social phobia. Second session: Patients learned how to deal with the barriers of mindfulness. Third session: Mindful breathing techniques were taught. Fourth session: Patients were taught how to be present in the moment. Fifth session: Patients learned how to accept certain situations, and also learned how to accept the fact that they were allowed to stay. Sixth session: Patients were taught that their thoughts were not always indicative of reality. Seventh session: The question, How can I protect myself in the best way possible? was answered. Eighth session: In a review, patients were expected to continue using all of the things that they had learned so far to deal with excessive mental rumination and not to avoid being with people in the future (21).

3.5. Statistics

Mean and standard deviation statistics were used at the descriptive level. Normal distribution assumptions and t-test assumptions had been checked before analyzing the data with two tests: the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S test) and measurements of skewness and kurtosis, which both indicated normal distribution. The Assumption of Normality asserts that the sampling distribution of the mean is normal. Finally, a paired sample t-test was used at the inferential level of data analysis to find the differences between the pre-test and post-test scores from SPIN and RSES. All of the aforementioned calculations were done through the use of SPSS-18 software.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics of the participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic Information of the Participantsa.

| Demographic Information | Experiment | Control |

|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 13 |

| Age of students | 14.5 ± 4.3 | 14.3 ± 4.9 |

| Age of parents | 42.3 ± 5.5 | 44.6 ± 5.3 |

| Parent’s education, y | 13.3 | 12.9 |

| Socio-economic level | Middle class | Middle class |

| History of psycho/pharmaco therapy | None | None |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

Differences among the means of the demographic data in the experimental and control groups were tested through an independent t-test for any significance. No evidence of significance was found.

In the next step, the data related to the frequency, mean, and standard deviation of the scores from SPIN and RSES of the female members of the control and experimental groups in the pre-test and the post-test were provided. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the data.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of the Data Collected from Pre-Tests and Post-Tests for SPIN and RSESa.

| Group | N | Pre-Test | Post-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | |||

| SPIN | 12 | 26.07 ± 8.534 | 21.5 ± 12.076 |

| RSES | 12 | 0.89 ± 5.80 | 2.58 ± 5.017 |

| Control | |||

| SPIN | 13 | 25.81 ± 6.760 | 25.92 ± 5.951 |

| RSES | 13 | 0.60 ± 5.46 | 0.62 ± 3.228 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

As it can be seen, the mean of the social anxiety scores of the experimental group in the post-test results shows a decrease compared to their pre-test results, and the mean of the self-esteem scores of the experimental group members in the post-test results shows an increase compared to their pre-test results. These changes are not observed in the control group. To test the significance of the observed differences, we needed to conduct a paired sample t-test, but first, we checked the normal distribution of the data.

The normal distribution assumptions had been confirmed. First, tests for skewness and kurtosis showed normality. Then, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S test) was used to confirm the results. Again, the Assumption of Normality asserts that the sampling distribution of the mean is normal.

A paired sample t-test was used to assess the significance of the differences of social anxiety and self-esteem among the subjects. The results of the tests are provided in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Paired Sample T-Test for SPIN and RSES in the Experimental Group.

| Experimental Group | Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Confidence Intervala | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | SPIN pre, SPIN post | 11.750 | 7.759 | 2.240 | 6.820 | 16.680 | 5.246 | 11 | 0.000 |

| Pair 2 | RSES pre, RSES post | -3.417 | 5.089 | 1.469 | -6.650 | -.183 | -2.326 | 11 | 0.040 |

a95% Confidence Interval of the Difference

Table 5. Paired Sample Test for SPIN and RSES in the Control Groupa.

| Experimental Group | Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Confidence Intervalb | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | SPIN pre SPIN post | 1.53846 | 5.09273 | 1.41247 | -1.53904 | 4.61597 | 1.089 | 12 | 0.297 |

| Pair 2 | RSES pre RSES post | 0.00000 | 0.57735 | .16013 | -0.34889 | 0.34889 | 0.000 | 12 | 1.000 |

aP ≤ 0.05.

b95% Confidence Interval of the Difference

As is shown in Table 4, for the experimental group, a paired sample t-test revealed a statistically reliable difference between the mean number of the SPIN pre-test and post-test results (t (11) = 5.246, P = .000, α =0.05). It also revealed a statistically reliable difference between the mean number of the RSES pre-test and post-test results (t (11) = -2.326, P =0.040, α =0.05).

In Table 5, for the control group, a paired sample t-test failed to reveal a statistically reliable difference between the mean number of the SPIN pre-test and post-test results (t (12) =1.089, P =.297, α =0.05). It also failed to reveal a statistically reliable difference between the mean number of the RSES pre-test and post-test results [t (12) =1.089, P =0.000, α = 0.05].

5. Discussion

The present study was conducted in order to examine the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on social anxiety disorder and self-esteem in female adolescents suffering from social anxiety. The results revealed that attending MBCT sessions significantly decreased social anxiety and increased self-esteem among the female adolescents suffering from social anxiety. These findings are in line with the results of studies that confirm the efficiency and effectiveness of this therapeutic approach in patients diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (22, 23) and comorbid disorders such as anxiety (24, 25) and depression (26-29), as well as the specific psychological symptoms of social anxiety such as mental rumination (9), lack of concentration or self-esteem (9), and general mental health (30-32).

Based on the first findings of the research, we concluded that MBCT decreases social anxiety. As indicated in the results, this approach can decrease social anxiety and its symptoms including physiological symptoms, fear, and avoidance. The main core in this intervention that is different from other approaches is awareness which leads to alternative responses to fear and anxiety in the mind and the body. Awareness can effectively control emotional reactions by involving higher-order functions of the brain such as attention, consciousness, tendency for kindness, curiosity, and compassion, and by inhibiting the performance of the limbic system (33). Thus, anxiety and depression could also decrease because these emotions are usually associated with worries about the future and distresses about the past. Therefore, MBCT techniques can help the anxious individual find better alternative responses when faced with social problems.

Another finding of this research was that MBCT intervention leads to an increase in self-esteem in adolescents diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. To explain this finding, it can be said that those suffering from social anxiety have lower self-esteem than normal people. Low self-acceptance is considered as the first characteristic of social phobia and in cognitive models of social anxiety, negative self-schema is considered as the most important component of social anxiety. It is often seen that those with social anxiety underestimate themselves, and this self-conception negatively influences their interactions with others. As mentioned above, the findings indicated that socially anxious people reported more negative self-expressions and more negative beliefs about self-evaluation than those who were not anxious (6, 34, 35). As these cognitions based on negative self-evaluation have important roles in the development and durability of social anxiety, we should expect relatively higher levels of self-esteem after MBCT intervention.

The present study has limitations which may restrict the generalizability of the results. First, this research was conducted on female adolescents, and considering the many differences between men and women, there are limitations with respect to effectively generalizing the results to male adolescents. Furthermore, since the therapist and the evaluator are the same person in this study, this could also have had a negative impact and created biases in the results. Also, due to the time limitations, the results were not followed up on; thus, a lack of information about the continuity of the subjects’ improvement process is another limitation. Relying merely on self-report tools to examine the results of therapy is considered as an additional limitation in interpreting the effectiveness of this therapy. Since MBCT has not yet been examined in adolescents with social anxiety disorder, all of the previous research topics and the existing theoretical background for this study are based on the results obtained from this type of therapy being applied in the treatment of adult patients suffering from social anxiety disorder and other psychological disorders; this difference in the subjects can also affect the reliability of results in the sense of imposing an additional bias. It is recommended that in future research, independent evaluators (aside from the therapist) determine the therapeutic achievements. Although the findings of this research confirmed the effectiveness of the cognitive therapy approach, it is suggested that the experimental studies be repeated with larger samples to reach a more definitive conclusion. It is also suggested that in future research, the effectiveness of MBCT on male adolescents suffering from social anxiety as well as other psychological disorders should be examined. Finally, if it is possible to track the results of MBCT in both short-term and long-term periods of time, we can likely talk more capably about the actual effectiveness of this type of therapy for social anxiety disorder.

In conclusion, the results indicated that MBCT is effective for the improvement of self-esteem and the decrease of social anxiety among female adolescents in Iran, and the results were in line with prior studies on adults, however limited they may be at this time.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the participants who made this study possible.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Study concept and design, Zahra Zeinodini; acquisition of data, Shima Ebrahiminejad; analysis and interpretation of data, Abbas Bakhshiour Roodsari; drafting of the manuscript, Shima Ebrahiminejad; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hamid Poursharifi; statistical analysis, Simasadat Noorbakhsh; administrative, technical, and material support, Zahra Zeinodini; study supervision, Simasadat Noorbakhsh.

References

- 1.Choate ML, Pincus DB, Eyberg S, Barlow DH. Parent-child interaction therapy for treatment of separation anxiety disorder in young children: A pilot study. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12(1):126–35. doi: 10.1016/s1077-7229(05)80047-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beidel DC, Turner SM. Shy children, phobic adults: Nature and treatment of social anxiety disorder. American Psychological Association Washington, DC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Young BJ, Ammerman RT, Sallee FR, Crosby L. Psychopathology of Adolescent Social Phobia. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2006;29(1):46–53. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-9021-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark DM, Ehlers A, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M, Grey N, et al. Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psych. 2006;74(3):568. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal ZV, Teasdale JD, Williams JM, Gemar MC. The mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy adherence scale: Inter‐rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. J Clin Psychol Psychother. 2002;9(2):131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabat‐Zinn J. Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin psychol. 2003;10(2):144–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn . 2010;19(2):597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisendrath SJ, Gillung E, Delucchi K, Mathalon DH, Yang TT, Satre DD, et al. A preliminary study: efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus sertraline as first-line treatments for major depressive disorder. Mindfulness. 2015;6(3):475–82. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, Cuijpers P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. J PSYCHOSOM RES. 2010;68(6):539–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association AP. American Psychiatric Association. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association WM. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Jama. 2013;310(20):2191. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for dsm-iv® axis i disorders (scid-i), clinician version, administration booklet. American Psychiatric Pub. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharifi V, Assadi SM, Mohammadi MR, Amini H, Kaviani H, Semnani Y, et al. A Persian translation of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: psychometric properties. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(1):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, Weisler RH. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). New self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:379–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momeni M. The effectiveness of EMDR and its reprocessing on treating social anxiety disorder. Tehran: Shahed University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg BG. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). 1965;61 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(4):623–42. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapurian R, Hojat M, Nayerahmadi H. Psychometric characteristics and dimensionality of a Persian version of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Percept Mot Skills. 1987;65(1):27–34. doi: 10.2466/pms.1987.65.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams JM, Russell I, Russell D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: further issues in current evidence and future research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(3):524–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Rector NA. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy for social anxiety disorder: An open trial. Cogn Behav Pract. 2009;16(3):276–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10(1):83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobkin PL, Zhao Q. Increased mindfulness – The active component of the mindfulness-based stress reduction program? Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(1):22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans S, Ferrando S, Findler M, Stowell C, Smart C, Haglin D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(4):716–21. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omidi A, Hamidian S, Mousavinasab SM, Naziri G. Comparison of the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy accompanied by pharmacotherapy with pharmacotherapy alone in treating dysthymic patients. IRCMJ. 2013;15(3) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.8024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omidi A, Mohammadkhani P, Mohammadi A, Zargar F. Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. IRCMJ. 2013;15(2):142–6. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coelho HF, Canter PH, Ernst E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Evaluating current evidence and informing future research. Th Res Prac. 2013;1(S):97–107. doi: 10.1037/2326-5523.1.s.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohlmeijer ET, Fledderus M, Rokx TAJJ, Pieterse ME. Efficacy of an early intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with depressive symptomatology: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Th. 2011;49(1):62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fledderus M, Bohlmeijer E, Pieterse M, Schreurs K. Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42(03):485–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychres. 2011;187(3):441–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown KW, Kasser T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Ind Res. 2005;74(2):349–68. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabat-Zinn J. Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hachette UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barlow DH. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. Guilford publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobson KS. Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]