Abstract

Background

Male suicide rates continued to increase in Scotland when rates in England and Wales declined. Female rates decreased, but at a slower rate than in England and Wales. Previous work has suggested higher than average rates in some rural areas of Scotland. This paper describes trends in suicide and undetermined death in Scotland by age, gender, geographical area and method for 1981 – 1999.

Methods

Deaths from suicide and undetermined cause in Scotland from 1981 – 1999 were identified using the records of the General Registrar Office. The deaths of people not resident in Scotland were excluded from the analysis. Death rates were calculated by area of residence, age group, gender, and method. Standardised Mortality Ratios (SMRs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for rates by geographical area.

Results

Male rates of death by suicide and undetermined death increased by 35% between 1981 – 1985 and 1996 – 1999. The largest increases were in the youngest age groups. All age female rates decreased by 7% in the same period, although there were increases in younger female age groups.

The commonest methods of suicide in men were hanging, self-poisoning and car exhaust fumes. Hanging in males increased by 96.8% from 45 per million to 89 per million, compared to a 30.7% increase for self-poisoning deaths. In females, the commonest method of suicide was self-poisoning. Female hanging death rates increased in the time period.

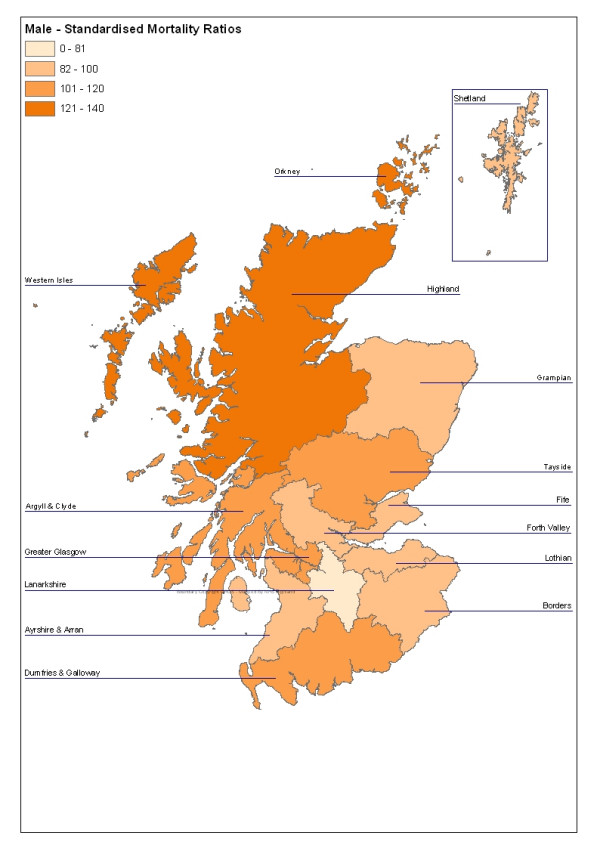

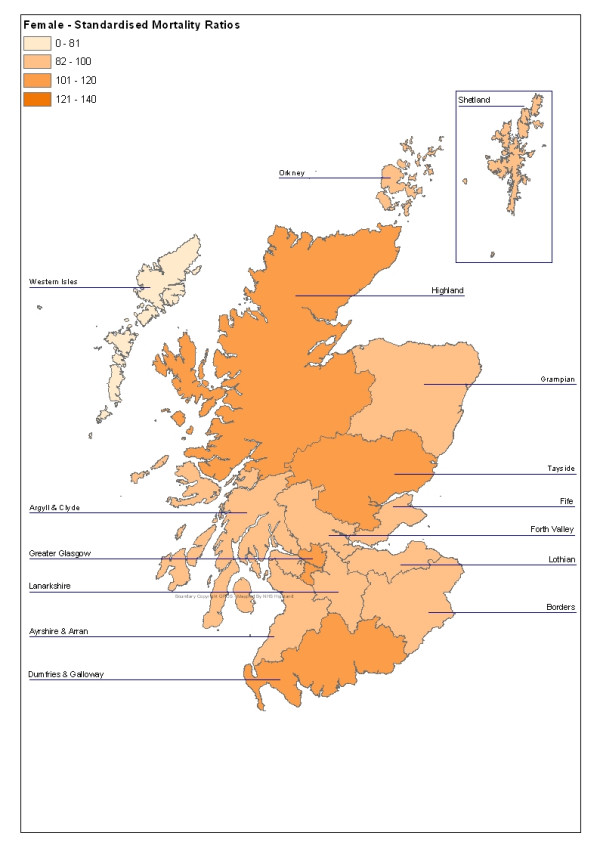

Male SMRs for 1981 – 1999 were significantly elevated in Western Isles (SMR 138, 95% CI 112 – 171), Highland (135, CI 125 – 147), and Greater Glasgow (120, CI 115 – 125). The female SMR was significantly high only in Greater Glasgow (120, CI 112 – 128).

Conclusion

All age suicide rates increased in men and decreased in women in Scotland in 1981 – 1999. Previous findings of higher than expected male rates in some rural areas were supported. Rates were also high in Greater Glasgow, one of the most deprived areas of Scotland. There were changes in the methods used, with an increase in hanging deaths in men, and a smaller increase in hanging in women. Altered choice of method may have contributed to the increased male deaths.

Background

Compared to the adjacent countries of England and Wales, Scotland had a low suicide rate through most of the twentieth century [1]. This did not appear to be explained by differences in recording of suicide [2]. Suicide rates in Scottish men increased in the 1970s and 1980s [3,4]. Rates in younger men continued to increase in the late 1980s [5] and early 1990s [6], at a time when male rates in England declined [7,8]. By contrast, female rates decreased in Scotland, although not as rapidly as in England and Wales [3].

Several authors have noted the importance of suicide in Scotland as a public health problem [9,10]. There was an increase in hanging and motor vehicle exhaust fumes as methods of male suicide in 1970 – 1989 and Pounder [5] suggested that choice of method might contribute to the increase in Scottish male rates, as some methods are associated with higher case fatality rates. Crombie [11] found that some areas had higher rates of male suicide than the Scottish average, mainly in rural areas. Access to particular methods of suicide may contribute to this [12]. Gender, age, suicide method and geographical area therefore appear to be important considerations in the epidemiology of suicide in Scotland. No recent summary of suicide trends in Scotland has been available, and this paper describes trends in relation to these factors.

Methods

We used anonymised information on deaths by suicide and undetermined deaths provided by the General Register Office for Scotland (GROS). Deaths registered during 1981 – 1999 were included if the cause of death was recorded as suicide or as undetermined cause (ICD-9 E950-E959 and E980-E989 respectively). Undetermined deaths were included as suicide deaths may be misattributed [13,14].

Population figures were taken from the GROS annual reports for the mid-year of each period. For analyses by area, if a death was registered away from the person's home address, the death was allocated to their area of residence, rather than the area in which they died. Deaths of people resident outside Scotland were identified using country codes, and were excluded. As far as possible, therefore, results reflect the rates of suicide and undetermined deaths of people resident in each area of Scotland. Standardised Mortality Ratios were calculated for National Health Service administrative areas, with 95% confidence intervals. In time period descriptions, the periods 1981 – 1985, 1986 – 1990, 1991 – 1995, and 1996 – 1999 were used. Data were analysed using Excel and SPSS.

Results

There were 14502 deaths recorded as suicide or undetermined cause in the time period. Of these deaths, 28.5% occurred in females (n = 4137) and 71.5% in males (n = 10365).

Gender and age group

Table 1 shows changes by gender. The male suicide rate for suicide and undetermined deaths increased from 187 per million in 1981 – 1985 to 252 per million in 1996 – 1999, an increase of 35%. In the same period, the female rate per million decreased from 88 to 82 per million, a 7% decrease. The female decline occurred between 1981 – 1985 and 1986 – 1999. By contrast, male rates increased between all time periods. The female: male rate ratio in 1981 – 1985 was 2.1:1 By 1996 – 1999 this had increased to 3.1:1.

Table 1.

Suicide and Undetermined Deaths in Scotland 1981 – 1999 By Gender and Time Period Rate per Million Population

| 1981 to 1985 | 1986 to 1990 | 1991 to 1995 | 1996 to 1999 | ||||||

| Gender | No. of deaths | Rate/million | No. of deaths | Rate/million | No. of deaths | Rate/million | No. of deaths | Rate/million | % change from first to last time period |

| Males | 2324 | 187 | 2,587 | 210 | 2,948 | 238 | 2,506 | 252 | 35% |

| Females | 1180 | 88 | 1,030 | 78 | 1,058 | 80 | 869 | 82 | -7% |

| Total | 3,504 | 136 | 3,617 | 142 | 4,006 | 156 | 3,375 | 165 | 21% |

Examining changes by age group in males (Table 2), there are increases in male rates in the under 15 years, 15– 24 year, 25 – 34 year and 35 – 44 year age groups, of 137%, 97%, 86% and 26% respectively. The increase in the youngest male age group, although based on very small numbers of deaths, occurred between 1986 – 90 and 1991 – 95. In the 15–24 and 25 – 34 year age groups, increases occurred in every time period. There were decreases in the 45 – 54 and 55 – 64 year age groups and increases, of 4% and 10%, in the 65 – 74 and 75 years and over age groups.

Table 2.

Suicide and Undetermined Deaths in Males in Scotland 1981 – 1999 By Age Group and Time Period

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–1999 | ||||||

| Age group | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | % change from first to last period |

| <15 years | 11 | 4.1 | 11 | 4.5 | 25 | 10.1 | 19 | 9.7 | 137% |

| 15–24 | 317 | 141.0 | 440 | 208.3 | 467 | 257.2 | 369 | 278.0 | 97% |

| 25–34 | 410 | 226.1 | 536 | 276.1 | 736 | 355.9 | 677 | 421.4 | 86% |

| 35–44 | 422 | 268.5 | 470 | 279.2 | 594 | 340.8 | 506 | 338.0 | 26% |

| 45–54 | 437 | 311.0 | 420 | 301.6 | 473 | 313.6 | 377 | 290.6 | -7% |

| 55–64 | 382 | 290.7 | 339 | 263.3 | 306 | 241.3 | 229 | 226.4 | -22% |

| 65–74 | 228 | 244.6 | 223 | 238.5 | 212 | 216.0 | 200 | 254.3 | 4% |

| 75+ | 117 | 253.6 | 148 | 287.8 | 135 | 253.6 | 129 | 278.8 | 10% |

| All Ages | 2,324 | 187.0 | 2,587 | 209.7 | 2,948 | 237.8 | 2,506 | 252.1 | 35% |

In women, there were increases in the three youngest age groups, with a 76% increase in rates in the under 15 year old group, 150% in the 15 – 24 year group and 37% in 25 – 34 year olds (Table 3). There were decreases in every older age group from 35 – 44 years to 75 years and over.

Table 3.

Suicide and Undetermined Deaths in Females in Scotland 1981 – 1999 By Age Group and Time Period

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–1999 | ||||||

| Age group | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | No. of deaths | Rate per million | % change from first to last period |

| <15 years | 7 | 2.7 | 7 | 3.0 | 7 | 3.0 | 9 | 4.8 | 76% |

| 15–24 | 70 | 32.4 | 89 | 44.1 | 100 | 57.6 | 103 | 81.0 | 150% |

| 25–34 | 141 | 78.9 | 174 | 91.4 | 217 | 106.4 | 172 | 108.3 | 37% |

| 35–44 | 179 | 112.3 | 158 | 93.3 | 192 | 109.1 | 157 | 103.9 | -8% |

| 45–54 | 231 | 154.9 | 151 | 103.3 | 179 | 115.0 | 153 | 115.1 | -26% |

| 55–64 | 264 | 176.3 | 187 | 129.6 | 138 | 98.4 | 96 | 86.7 | -51% |

| 65–74 | 174 | 136.5 | 153 | 122.5 | 107 | 84.8 | 101 | 102.6 | -25% |

| 75+ | 114 | 114.3 | 111 | 103.0 | 118 | 108.3 | 78 | 87.0 | -24% |

| All Ages | 1,180 | 88.4 | 1,030 | 78.1 | 1,058 | 80.1 | 869 | 82.4 | -7% |

Method of suicide

The commonest methods of suicide and undetermined deaths in men were hanging, strangulation and suffocation, poisoning with solid or liquid substances, drowning, use of gases and vapours and jumping from high places (Table 4). Hanging, strangulation and suffocation in males had a similar rate to poisoning with solid or liquid substances in 1981 – 1985, but by 1996 – 1999 it had increased by 96.8% from 45 per million to 89 per million, compared to a 30.7% increase for self-poisoning deaths, from 46 per million to 60 per million. Deaths from jumping and cutting also increased, by 44.2% and 18.8% respectively. 'Other gases and vapours', predominantly car exhaust deaths (data not presented), decreased slightly from the first to last periods, but this concealed a substantial increase between 1981 – 1985 and 1986 – 1990, followed by a decrease in 1996 – 1999. Unspecified means increased by 70.9% from 14 to 23 per million.

Table 4.

Methods of Suicide and Undetermined Death in Males in Scotland 1981 – 1999 By Time Period

| 1981 to 1985 | 1986 to 1990 | 1991 to 1995 | 1996 to 1999 | ||||||

| Primary Cause | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | % change from first to last time period |

| Solid or liquid substances | 572 | 46 | 594 | 48 | 768 | 62 | 598 | 60 | 30.7 |

| Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 562 | 45 | 630 | 51 | 774 | 62 | 880 | 89 | 96.8 |

| Submersion(drowning) | 353 | 28 | 417 | 34 | 358 | 29 | 268 | 27 | -5.1 |

| Other gases and vapours | 288 | 23 | 428 | 35 | 448 | 36 | 225 | 23 | -2.3 |

| Other, unspecified means | 169 | 14 | 170 | 14 | 226 | 18 | 231 | 23 | 70.9 |

| Firearms and explosives | 166 | 13 | 119 | 10 | 114 | 9 | 66 | 7 | -50.3 |

| Jumping from high place | 163 | 13 | 176 | 14 | 203 | 16 | 188 | 19 | 44.2 |

| Cutting and piercing instruments | 40 | 3 | 38 | 3 | 38 | 3 | 38 | 4 | 18.8 |

| Gases in domestic use | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 33.4 |

| Late effects of injury | 3 | . 4 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 99.9 |

| Total | 2,324 | 187 | 2,587 | 210 | 2,948 | 238 | 2,506 | 252 | 34.8 |

In females, the commonest methods of suicide and undetermined death were poisoning with solid or liquid substances, hanging, strangulation and suffocation, and drowning (Table 5). Self-poisoning decreased by 4.8% between first and last periods from 45 to 43 per million, while drowning, and jumping from high places decreased by 54.1% and 30.3% respectively. Gases and vapours showed an increase but, as in males, the rate was higher in the middle two time periods. The rate of hanging, strangulation and suffocation deaths increased by 53.5%. There was an increase in unspecified means of suicide, from 4 to 8 per million.

Table 5.

Methods of Suicide and Undetermined Death in Females in Scotland 1981 – 1999 By Time Period

| 1981 to 1985 | 1986 to 1990 | 1991 to 1995 | 1996 to 1999 | ||||||

| Primary Cause | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | % change from first to last time period |

| Solid or liquid substances | 601 | 45 | 577 | 44 | 570 | 43 | 452 | 43 | -4.8 |

| Submersion(drowning) | 248 | 19 | 159 | 12 | 132 | 10 | 90 | 9 | -54.1 |

| Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 127 | 10 | 95 | 7 | 134 | 10 | 154 | 15 | 53.5 |

| Jumping from high place | 89 | 7 | 77 | 6 | 67 | 5 | 49 | 5 | -30.3 |

| Other, unspecified means | 60 | 4 | 53 | 4 | 81 | 6 | 83 | 8 | 75.1 |

| Other gases and vapours | 31 | 2 | 51 | 4 | 50 | 4 | 30 | 3 | 22.5 |

| Firearms and explosives | 13 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.4 | -68.9 |

| Cutting and piercing instruments | 9 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | -25.0 |

| Late effects of injury | 2 | 0.4 | - | - | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Gases in domestic use | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0.4 | - | - | - |

| Total | 1,180 | 88 | 1,030 | 78 | 1,058 | 80 | 869 | 82 | -6.8 |

Geographical areas

In the nineteen-year period as a whole, there was substantial geographical variation (Figures 1 and 2). The highest male rates were in Western Isles, Highland, Orkney, Greater Glasgow and Tayside (Table 6). When considered as Standardised Mortality Ratios, Western Isles, Highland and Greater Glasgow were statistically significantly elevated (Table 6). Six areas, Fife, Ayrshire and Arran, Forth Valley, Lothian, Borders and Lanarkshire had significantly lower SMRs than the Scottish average.

Figure 1.

Male Standardised Mortality Ratios for Suicide and Undetermined Deaths in Scotland, 1981 – 1999 by Area

Figure 2.

Female Standardised Mortality Ratios for Suicide and Undetermined Deaths in Scotland, 1981 – 1999 by Area

Table 6.

Male Standardised Mortality Ratios by Health Service Area Suicide and Death by Undetermined Cause in Scotland 1981 – 1999

| Health Board of Residence | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | Standardised Mortality Ratio | ||

| Ratio | LCI | UCI | |||

| Argyll & Clyde | 909 | 225 | 103 | 97 | 110 |

| Ayrshire & Arran | 676 | 197 | 91 | 84 | 98 |

| Borders | 176 | 186 | 84 | 72 | 97 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | 301 | 223 | 101 | 90 | 113 |

| Fife | 634 | 197 | 90 | 83 | 97 |

| Forth Valley | 496 | 197 | 89 | 82 | 98 |

| Grampian | 1,050 | 219 | 99 | 93 | 105 |

| Greater Glasgow | 2,252 | 264 | 120 | 115 | 125 |

| Highland | 555 | 294 | 135 | 125 | 147 |

| Lanarkshire | 907 | 174 | 81 | 75 | 86 |

| Lothian | 1,399 | 202 | 90 | 85 | 95 |

| Orkney | 50 | 274 | 124 | 92 | 164 |

| Shetland | 47 | 214 | 99 | 72 | 133 |

| Tayside | 828 | 231 | 105 | 98 | 112 |

| Western Isles | 85 | 300 | 138 | 112 | 171 |

| Scotland | 10,365 | 220 | 100 | - | - |

In women, the highest rates were in Glasgow, Tayside, Highland and Dumfries and Galloway (Table 7). Only the Greater Glasgow SMR was significantly elevated. One area, Lanarkshire, had a significantly low female SMR.

Table 7.

Female Standardised Mortality Ratios by Health Service Area Suicide and Death by Undetermined Cause in Scotland 1981 – 1999

| Health Board of Residence | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | Standardised Mortality Ratio | ||

| Ratio | LCI | UCI | |||

| Argyll & Clyde | 330 | 77 | 93 | 84 | 104 |

| Ayrshire & Arran | 290 | 78 | 95 | 84 | 106 |

| Borders | 83 | 81 | 95 | 77 | 118 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | 122 | 85 | 101 | 84 | 120 |

| Fife | 277 | 82 | 100 | 89 | 112 |

| Forth Valley | 195 | 73 | 89 | 77 | 102 |

| Grampian | 383 | 77 | 95 | 86 | 105 |

| Greater Glasgow | 921 | 99 | 120 | 112 | 128 |

| Highland | 169 | 86 | 105 | 91 | 123 |

| Lanarkshire | 366 | 66 | 83 | 75 | 92 |

| Lothian | 598 | 81 | 97 | 90 | 105 |

| Orkney | 15 | 80 | 98 | 55 | 162 |

| Shetland | 16 | 74 | 95 | 54 | 154 |

| Tayside | 357 | 92 | 110 | 99 | 122 |

| Western Isles | 15 | 53 | 65 | 36 | 107 |

| Scotland | 4,137 | 82 | 100 | - | - |

There were changes within areas over the period studied. Male rates increased in all fifteen NHS Board areas (Table 8). The smallest percentage increases were in Orkney, Highland and Greater Glasgow, three of the areas with the highest male rates in the first time period. Shetland and Western Isles had large percentage increases, but this was based on small numbers of suicide and undetermined cause deaths. The largest increases in mainland Scottish Board areas were in Argyll and Clyde (62%), Borders (60%), Forth Valley 59%), Ayrshire and Arran (56%) and Grampian (49%).

Table 8.

Male Deaths from Suicide and Undetermined Cause in Scotland 1981 – 1999 Rates By Health Service Area and Time Period

| 1981 to 1985 | 1986 to 1990 | 1991 to 1995 | 1996 to 1999 | ||||||

| Primary Cause | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | % change from first to last time period |

| Argyll & Clyde | 190 | 175 | 212 | 199 | 272 | 259 | 235 | 283 | 62 |

| Ayrshire & Arran | 143 | 158 | 161 | 178 | 194 | 214 | 178 | 246 | 56 |

| Borders | 31 | 128 | 41 | 167 | 62 | 245 | 42 | 205 | 60 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | 71 | 201 | 74 | 209 | 79 | 220 | 77 | 269 | 34 |

| Fife | 148 | 177 | 155 | 183 | 169 | 198 | 162 | 239 | 35 |

| Forth Valley | 102 | 154 | 127 | 192 | 136 | 205 | 131 | 245 | 59 |

| Grampian | 219 | 181 | 258 | 208 | 291 | 224 | 282 | 270 | 49 |

| Greater Glasgow | 551 | 234 | 565 | 252 | 666 | 304 | 470 | 270 | 15 |

| Highland | 131 | 273 | 155 | 315 | 144 | 284 | 125 | 305 | 12 |

| Lanarkshire | 195 | 140 | 242 | 177 | 255 | 187 | 215 | 197 | 40 |

| Lothian | 307 | 172 | 350 | 195 | 408 | 223 | 334 | 222 | 29 |

| Orkney | 13 | 275 | 11 | 233 | 15 | 308 | 11 | 281 | 2 |

| Shetland | 12 | 202 | 10 | 179 | 7 | 121 | 18 | 388 | 92 |

| Tayside | 193 | 205 | 200 | 214 | 230 | 242 | 205 | 272 | 33 |

| Western Isles | 18 | 230 | 26 | 343 | 20 | 274 | 21 | 376 | 64 |

| Scotland | 2,324 | 187 | 2,587 | 210 | 2,948 | 238 | 2,506 | 252 | 35 |

In females, rates changed little or decreased in all mainland Boards other than Argyll and Clyde (16.9% increase) (Table 9). Rates increased in Orkney, Shetland and Western Isles, although these were based on very small numbers of deaths. The greatest declines in mainland Board areas were in Ayrshire and Arran (30% decrease) and Grampian (27.9% decrease).

Table 9.

Female Deaths from Suicide and Undetermined Cause in Scotland 1981 – 1999 Rates By Health Service Area and Time Period

| 1981 to 1985 | 1986 to 1990 | 1991 to 1995 | 1996 to 1999 | ||||||

| Primary Cause | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | No. of Deaths | Rate/million | % change from first to last time period |

| Argyll & Clyde | 96 | 82 | 73 | 64 | 76 | 68 | 85 | 96 | 17 |

| Ayrshire & Arran | 88 | 90 | 73 | 75 | 80 | 82 | 49 | 63 | -30 |

| Borders | 26 | 98 | 20 | 75 | 18 | 66 | 19 | 86 | -12 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | 34 | 91 | 29 | 77 | 32 | 84 | 27 | 89 | -2 |

| Fife | 79 | 89 | 76 | 85 | 69 | 77 | 53 | 74 | -18 |

| Forth Valley | 53 | 75 | 44 | 63 | 55 | 78 | 43 | 76 | 0.3 |

| Grampian | 133 | 105 | 85 | 66 | 84 | 63 | 81 | 76 | -28 |

| Greater Glasgow | 270 | 104 | 238 | 97 | 235 | 98 | 178 | 94 | -10 |

| Highland | 41 | 82 | 40 | 79 | 59 | 112 | 29 | 68 | -17 |

| Lanarkshire | 98 | 67 | 93 | 64 | 93 | 64 | 82 | 71 | 7 |

| Lothian | 165 | 85 | 156 | 81 | 143 | 73 | 134 | 84 | -0.3 |

| Orkney | 2 | 41 | 2 | 41 | 3 | 60 | 8 | 202 | 390 |

| Shetland | 1 | 17 | 4 | 72 | 7 | 125 | 4 | 88 | 412 |

| Tayside | 91 | 88 | 93 | 92 | 101 | 99 | 72 | 89 | 0.6 |

| Western Isles | 3 | 38 | 4 | 53 | 3 | 41 | 5 | 88 | 130 |

| Scotland | 1,180 | 88 | 1,030 | 78 | 1,058 | 80 | 869 | 82 | -7 |

Discussion

The epidemiology of suicide in Scotland has changed greatly between 1981 and 1999. Male suicide rates have increased in all age groups up to and including 35 – 44 years. The highest male suicide and undetermined death rates in 1996 – 1999 were in the 25 – 34 year age group. In women, rates dropped in age groups from 35 – 44 years up to and including 75 years and over. Rates increased in younger women.

There is limited information on the factors underlying individual deaths from suicide in Scotland. Squires and Gorman [15] reviewed the deaths by suicide of a group of young men in Lothian, and reported that a third had experienced recent relationship difficulties with a partner. Half of the group studied had a previous history of attempted suicide. Cavanagh et al [16] reported largely similar findings in a case control study in south-east Scotland. The group who had died by suicide had an odds ratio of 9.0 (95% CI 1.3 – 399) for current family problems, and an odds ratio of 5.0 (95% CI 1.1 – 47) for physical health problems. There was felt to be limited scope to intervene in suicide and deliberate self-harm through family health services because of limited contact, and non-specific presentation of problems [15,17].

Some methods of self-harm have higher case fatality rates [18]. Firearms have the highest case fatality rates, followed by drowning and hanging [19,20]. The most striking changes in male suicide methods in Scotland were the marked increase in hanging deaths, and the increase and subsequent decrease in deaths from 'other gases and vapours', which are mainly car exhausts. It seems likely that the decrease in motor vehicle exhaust fume deaths was related to the introduction of catalytic converters. Not all countries have reported a decrease in suicide from motor vehicle exhausts after catalytic converter introduction [21], but deaths in England decreased [22]. The reduction in deaths from motor vehicle exhaust fumes in England and Wales was associated with an increase in hanging deaths [7]. In Scotland, our data suggest that hanging deaths were increasing in men before deaths from motor vehicle exhaust fumes began to decline. The increase in hanging also appears greater than the decrease in motor vehicle exhaust deaths. The relationship between vehicle exhaust fume and hanging deaths in Scotland does not appear to be identical to that reported in England and Wales, and deserves further investigation.

The difference between areas was also of note. The lower rates of increase in the areas with the highest initial rates may reflect to regression to the mean. Method availability [23] may be important in rural/urban differences. Obafunwa and Busuttil [24] reported that, within the Lothian region of Scotland, hanging was commoner in younger deaths, while use of car exhaust fumes for suicide was particularly important in rural areas [24,25]. In Lothian, an area that includes the capital city of Scotland, suicide by firearms was uncommon. Previous work has suggested higher rates of male suicide in some rural parts of Scotland [11]. Stark et al [12] have suggested that this may be related to the use of methods of self-harm in rural areas, such as firearms, with a high case fatality rate. Gunnell and colleagues [26] have argued, in relation to England and Wales, that changes in method preference, and therefore in case fatality, should be considered before concluding that changes must relate to social trends.

Availability of method would not explain the differences between apparently similar rural areas. Previous work has found that deprived areas of Scotland tend to have higher suicide rates [27,28]. Deprived areas in Scotland were reported to have had the greatest increase in young male suicide between 1981 – 3 and 1991 – 3 [29]. Greater Glasgow, the non-rural area with the highest rate over the time period, is an area with substantial deprivation. Rural deprivation is difficult to measure, and recent work suggests that rural areas of Scotland may suffer greater levels of deprivation than had been realised. It is possible that rural deprivation is underestimated, and deprivation may explain more of the elevation in some rural areas than has been assumed in the past.

Using routine information allowed a large number of suicide and undetermined deaths to be included in this series. There are, however, limitations to the use of anonymised routine data. No qualitative information was available, and our exploration of the data was limited to trends with no examination of possible underlying causes. The increase in the rate of deaths recorded as suicide or undetermined cause of death, but where no detail on method was included, could conceal recent trends. The increase as a percentage of relevant registrations was small, however, increasing from 7.5% in the first period to 9.1% in the last period studied. The classification of deaths as suicide is often difficult, but the inclusion of undetermined deaths as well as deaths recorded as suicide should have helped to minimise bias from under identification [14,30]. Squires et al [31] reported that improved communication between pathologists and the Registrar General for Scotland from 1994 on was associated with a decrease in undetermined deaths and in increase in deaths coded as being caused by dependent or non-dependent use of drugs. It is possible, therefore, that the figures for the final two periods may under-represent deaths that would have been identified as 'unidentified' in the earlier periods. Using information on Scottish residents only allowed identification of the suicide rates of local populations. Deaths of non-residents can account for up to 10% of all suicide and undetermined cause deaths in some rural areas of Scotland [12]. Our findings indicate that, even when these deaths are excluded, rates remain increased in some rural areas.

Conclusions

A divergence between male rates in England and Wales and in Scotland, and in male and female rates within Scotland, had been identified for the first part of the time period described here. This work found that male rates of suicide and undetermined death continued to increase in Scotland, but also identifies increases in younger female age groups. Examination of changes in method by male and female age group will help to establish whether changes in case fatality because of altered method choice [26] may be part of the explanation for these findings. The shift to hanging seems to be a significant trend in men in Scotland. It will be important to understand the reasons for this to allow appropriate intervention strategies to be considered.

Some rural areas of Scotland had significantly elevated male suicide rates. We have suggested that access to lethal means of suicide may be one contributing mechanism for this, and have also noted the higher than expected suicide numbers in some rural occupations [12]. Rural areas are subject to poverty of income and opportunity, so it is also possible that rural deprivation may play an important part. Occupational associations of suicide in Scotland deserve further exploration. Examination of the association between deprivation, rurality and suicide may assist in the identification of possible interventions in rural Scotland.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CS had the idea for the study, wrote the grant application, contributed to the design and interpretation and drafted the paper. Diane Gibbs and Tracey Rapson analysed the data. Paddy Hopkins contributed to the design, undertook part of the analysis, and commented on the interpretation of the results. Alan Belbin and Alistair Hay contributed to the design and helped interpret the results. All authors read and approved the final draft of the paper.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken with a grant awarded by the Scottish Executive's Remote and Rural Areas Resource Initiative. NHS Highland supplied staff time from CS and PH. Prof. David Gunnell of the University of Bristol, Mike Muirhead of ISD, Professor David Godden of the University of Aberdeen and Brodie Paterson of the University of Stirling provided helpful advice during the study.

Contributor Information

Cameron Stark, Email: c.stark@abdn.ac.uk.

Paddy Hopkins, Email: paddy.hopkins@hhb.scot.nhs.uk.

Diane Gibbs, Email: diane.gibbs@isd.csa.scot.nhs.uk.

Tracey Rapson, Email: tracey.rapson@isd.csa.scot.nhs.uk.

Alan Belbin, Email: alan.belbin@gp55215.highland-hb.scot.nhs.uk.

Alistair Hay, Email: alistair.hay@hpct.scot.nhs.uk.

References

- Kreitman N. Suicide in Scotland in comparison with England and Wales. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;121:83–87. doi: 10.1192/bjp.121.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross O, Kreitman N. A further investigation of differences in suicide rates in England and Wales and of Scotland. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;127:575–582. doi: 10.1192/bjp.127.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie IK. Trends in suicide and unemployment in Scotland, 1976 – 86. BMJ. 1989;298:782–784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie IK. Suicide in England and Wales and in Scotland. An examination of divergent trends. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:529–532. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pounder DJ. Changing patterns of male suicide in Scotland. Forensic Sci Int. 1991;51:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(91)90207-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, Matthewson F. Differences in suicide rates may be even more pronounced. BMJ. 2000;320:1146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7242.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure GMG. Changes in suicide in England and Wales, 1960 – 1997. Br J Psych. 2000;176:64–67. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamey G. Suicide rate is decreasing in England and Wales. BMJ. 2000;320:75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. The changing pattern of mortality in young adults aged 15 to 34 in Scotland between 1972 and 1992. Scot Med J. 1994;39:144–145. doi: 10.1177/003693309403900507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramayya A, Campbell M, Callender JS. Death by suicide in Grampian 1974 – 1990. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996;54:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie IK. Suicide among men in the highlands of Scotland. BMJ. 1991;302:761–762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C, Matthewson F, Oates K, Hay A. Suicide in the Highlands of Scotland. Health Bull (Edinb) 2002;60:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough BM. Poisoning cases: suicide or accident. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:526–530. doi: 10.1192/bjp.124.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Bunting J. Trends in suicide in England and Wales, 1982 – 1996. Population Trends. 1998;92:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires T, Gorman D. Suicide by young men in Lothian 1993 and 1994. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996;54:458–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JT, Owens DG, Johnstone EC. Life events in suicide and undetermined death in south-east Scotland: a case-control study using the method of psychological autopsy. Soc Psych Psych Epidemiol. 1999;34:645–650. doi: 10.1007/s001270050187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman D, Masteron S. General practice consultation patterns before and after intentional overdose: a matched case control study. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:102–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JJ. Lethality of suicidal methods and suicide risk: two distinct concepts. Omega. 1974;5:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer RS, Miller TR. Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1885–1891. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, Catlin SN, Buka SL. Lethality of firearms relative to other suicide methods: a population based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:120–124. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routley VH, Ozanne-Smith J. The impact of catalytic converters on motor vehicle exhaust gas suicides. Med J Aust. 1998;168:65–67. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb126713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos T, Appleby L, Kierhan K. Changes in rates of suicide in car exhaust asphyxiation in England and Wales. Psychol Med. 2001;31:935–939. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701003920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnley IH. Socioeconomic and spatial differentials in mortality and means of committing suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1985 – 91. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:687–698. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obafunwa JO, Busuttil A. A review of completed suicides in the Lothian and Borders Region of Scotland 1987 – 1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:100–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00805630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busuttil A, Obafunwa JO, Ahmed A. Suicidal inhalation of vehicular exhaust in the Lothian and Borders region of Scotland. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1994;13:545–550. doi: 10.1177/096032719401300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D, Middleton N, Frankel S. Method availability and the prevention of suicide – a re-analysis of secular trends in England and Wales 1950 – 1975. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s001270050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoone P, Boddy FA. Deprivation and mortality in Scotland, 1981 and 1991. BMJ. 1994;309:1465–1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6967.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren G, Bain M. Deprivation and Health in Scotland: Insights from NHS Data. Edinburgh: Information and Statistics Division National Health Service in Scotland; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McLoone P. Suicide and deprivation in Scotland. BMJ. 1996;312:543–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7030.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohberg A, Lonnqvist J. Suicides hidden among undetermined deaths. Acta Psychiatr Scandi. 1998;98:214–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires T, Gorman D, Arrundale J, Platt S, Fineron P. Reduction in drug related suicide in Scotland 1990 – 1996: an artefactual explanation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:436–437. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.7.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]