Abstract

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are adhesion-dependent cells that require cultivation in colonies to maintain growth and pluripotency. Robust differentiation protocols necessitate single cell cultures that are achieved by use of ROCK (Rho kinase) inhibitors. ROCK inhibition enables maintenance of stem cell phenotype; its effects on metabolism are unknown. hPSCs were exposed to 10 μM ROCK inhibitor for varying exposure times. Pluripotency (TRA-1-81, SSEA3, OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) remained unaffected, until after prolonged exposure (96 hrs). Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolomics analysis identified differences between ROCK-treated and untreated cells as early as 12 hrs. Exposure for 48 hours resulted in reduction in glycolysis, glutaminolysis, the citric acid (TCA) cycle as well as the amino acids pools, suggesting the adaptation of the cells to the new culture conditions, which was also reflected by the expression of the metabolic regulators, mTORC1 and tp53 and correlated with cellular proliferation status. While gene expression and protein levels did not reveal any changes in the physiology of the cells, metabolomics revealed the fluctuating state of the metabolism. The above highlight the usefulness of metabolomics in providing accurate and sensitive information on cellular physiological status, which could lead to the development of robust and optimal stem cell bioprocesses.

Human pluripotent stem cells have the ability to self-renew and differentiate to any cell type of the body, which renders them important to both research and potential regenerative medicine therapeutic applications1. hPSCs, both embryonic and induced pluripotent, are optimally maintained in colonies yet efficient and robust differentiation protocols are best achieved by single cell cultures2. Addressing challenges of directed differentiation in vitro, such as scaling-up of the cultures, elimination of xeno-components, efficiency, etc., as well as understanding the epigenetic differences on methylation patterns between hESCs and hiPSCs3, requires precise and sensitive monitoring of cell cultures that provides insightful information on cellular state.

Metabolism is the set of life-sustaining chemical transformations within the cells that is considered as the most dynamic. It directly reacts with the environment and provides fast response to environmental perturbations. Metabolism is simultaneously both autonomous and inter-connected with the other levels of the cellular function, such as protein and gene expression as well epigenetic changes. Emerging evidence suggests that pluripotent stem cells are metabolically distinct from their differentiated counterparts and that these metabolic properties are important for stem cell identity. Furthermore, molecular regulators of energy metabolism have essential roles in stem cell fate, in particular, the decision to self-renew or differentiate and stem cells respond to fluctuations in energy states in vivo4. Specifically, metabolic activity and metabolite pools affect stem cell epigenetic mechanisms in a direct way5 influencing stem cell differentiation potential6,7,8. It is of great importance to define cell state - undifferentiated or differentiated - by its metabolic properties as this is in direct correlation with the cells’ potential.

Single cell cultures in suspension of hPSCs undergo apoptosis despite the use of culture conditions conducive to stem cell maintenance9,10. This problem has been addressed with the inhibition of ROCK (Rho-associated protein kinase), a serine-threonine kinase that phosphorylates and activates the myosin II pathway11,12,13,14,15,16 resulting in the maintenance of the differentiation potential for up to 72 hours, which is considered to be primarily mediated via the inhibition of an E-cadherin-dependent apoptotic pathway17,18,19,20. The most effective ROCK inhibitor is Y-2763221. hPSCs colonies, both hESCs and hiPSCs, are most commonly treated with 10 μM of Y-27632 prior to dissociation of the colonies into single cells22,23,24. With this protocol, single cell survival is maintained for up to 3 weeks and stem cell phenotype along with differentiation capability into all lineages are sustained11. Until now, it has been assumed that ROCK inhibition does not affect physiology since the hPSCs retain their stemness and survive25.

Herein, we have undertaken an in-depth assessment of the effect of ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) on the dynamic metabolism of hPSCs over a 96-hour culture period5,26,27. Whereas no differences were observed in the pluripotency and viability of hESCs and hiPSCs on gene and protein expression levels, differences in metabolism were detected. Specifically, metabolomics analysis was able to detect changes on the metabolic physiology of the cells as early as 12 h of ROCK inhibitor treatment. Existing metabolic switches on hESCs and hiPSCs were similar on both cell types up to 48 h of exposure to Y-27632, with 24 h exposure being identified to be critical as a turning point in metabolism. Correlating with these metabolic changes, a differential expression of the metabolic regulators, p5328,29 and mTORC14,30, was observed. The above indicate a dynamic process of adaptation of the cells to the altered environment, which is mostly projected to the metabolic level.

Results

hPSCs maintain pluripotency phenotype up to 48 h of exposure to ROCK inhibitor

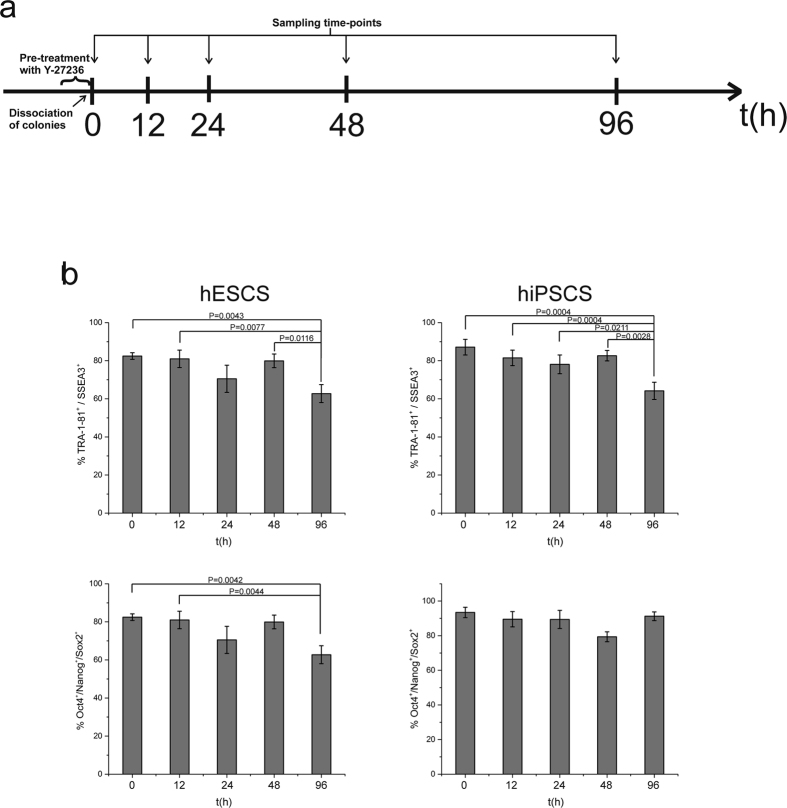

The effects of Y-27632 exposure on both hESCs and hiPSCs were evaluated by assessing gene and protein expression of pluripotency markers. Specifically, TRA-1-81 and SSEA3 expression indicated that the cells retained these pluripotency markers up to 48 h of exposure, whereas there was a reduction at 96 h in both cell types (p < 0.05; Fig. 1b). Intracellular expression of Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 indicated maintenance of stemness at high levels (over 67% for hESCs and 80% for hiPSCs), which is reduced at 96 h exposure for hESCs (p < 0.05; Fig. 1b). Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 expression did not differ at any time-point evaluated (data not shown). Consequently, gene and protein expression showed that the pluripotency phenotype remained constant for at least 48 hours after ROCK exposure and was similar to the untreated control. In all cases, cell viability was high (data not shown). Immunostaining for Oct4 and Sox2 confirmed the maintenance of pluripotency, apart from the 96 h time-point in hESCs when the staining appeared to be weaker (Supplementary Figure 1), in agreement with the flow cytometry results (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Assessment of pluripotency phenotype by conventional markers following exposure to ROCK inhibitor.

(a) Experimental design. hPSCs were pre-treated with 10 μΜ Y-27236 ROCK inhibitor for 1–2 hours. Then, colonies were dissociated into single cells and exposed to 10 μΜ Y-27236 ROCK inhibitor. Samples were collected at five time-points: 0 h were untreated with cells remained in colonies whereas single cells were sampled at all other time-points (12 h, 24 h, 48 h and 96 h). (b) hPSC cell phenotype by flow cytometry and qRT-PCR was maintained for at least 48 hours following exposure to ROCK inhibitor, with reduction in stemness phenotype noted by 96 hours. *p < 0.05.

Metabolomics analysis reveals changes in metabolism

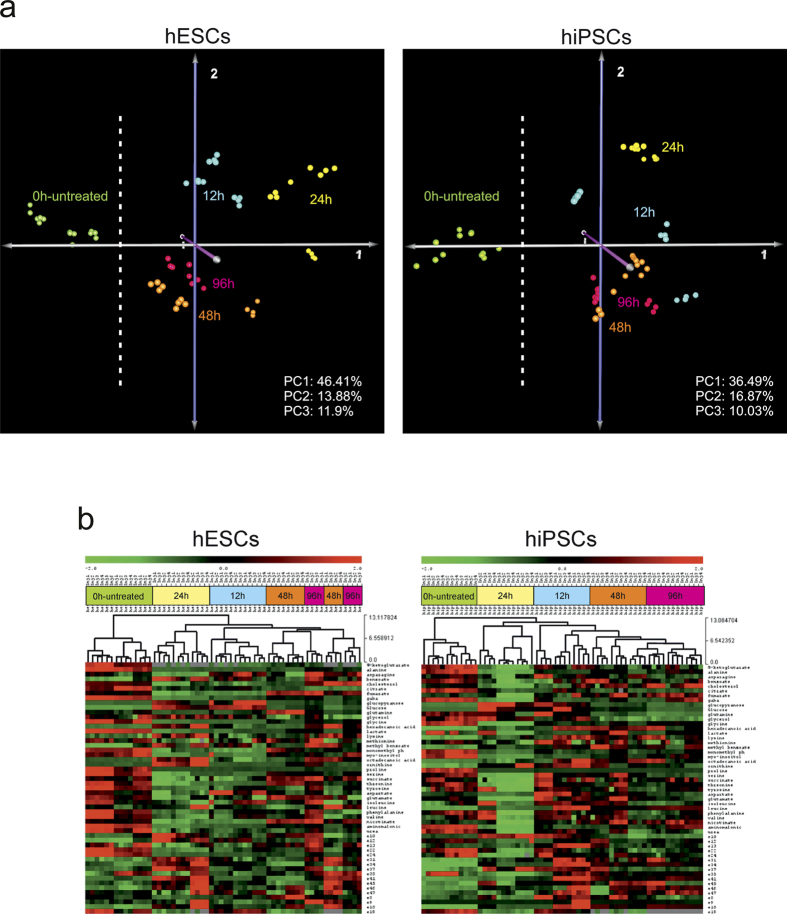

Multivariate statistical analysis revealed that 0 h–untreated cells (grown in colonies and not exposed to Y-27632) had discrete metabolism compared to those exposed to Y-27632 as early as 12 hrs, as highlighted by Hierarchical Clustering (HCL) analyses and heatmaps (Fig. 2b). Grouping of the metabolic profiles from cells exposed 48 h and 96 h to ROCK inhibitor demonstrated that prolonged exposure resulted in adapted cellular physiology not as discrete as that of cells exposed for 12 h and 24 h, as elucidated by the grouping in Principal Components Analysis (PCA) graphs (Fig. 2a). Alas, the distinct grouping of the hESCs and hiPSCs at 12 h exposure indicates a different physiological response of the cells (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Clustering (HCl).

(a) PCA graphs show the difference of 0 h-untreated profiles of both hESCs and hiPSCs compared with that of the other time-points. Interestingly, profiles of the 0 h (green) for both hPSCs are grouped in the left side of the graphs. It can also be observed that 48 h and 96 h profiles are grouped together and seems closer compared to the highest spreading of 12 h and 24 h profiles. ROCK inhibitor changed metabolic physiology compared with that of the 0 h untreated cells. (b) HCL and heatmaps indicate that clustering of metabolic profiles is similar for both types of hPSCs and dependent on exposure time to ROCK inhibitor. Metabolism over time appear similar for both cell types throughout the experimental process, though not identical. 0 h-untreated profiles form a discrete cluster in both types of cells. (Distance Metric: Euclidean on standardized relative peak areas – stRPAs).

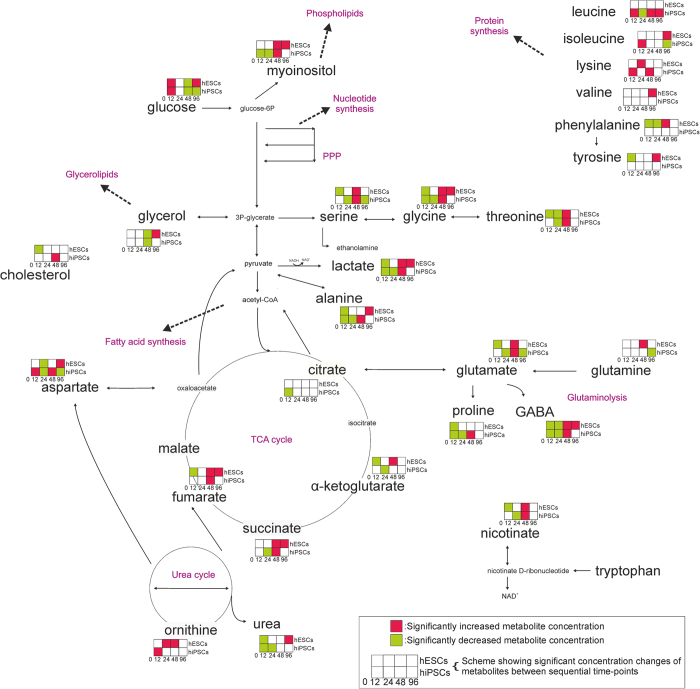

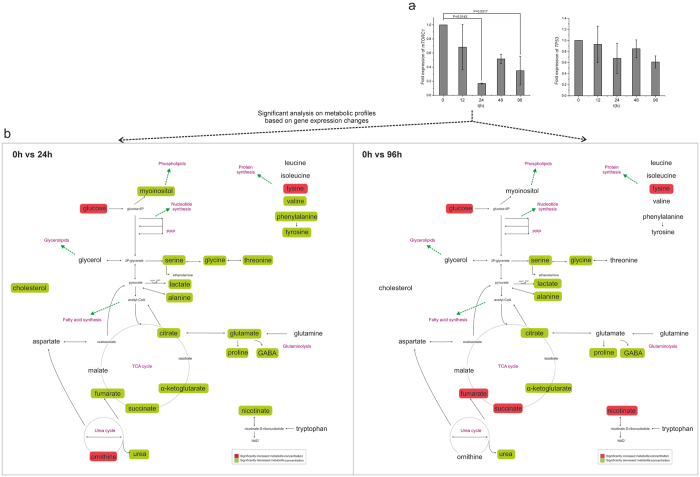

To further understand how cellular physiology changed with culture time, an in-depth assessment of the metabolic transitions was undertaken: consecutively from 0 h to 12 h, 12 h to 24 h, 24 h to 48 h and 48 h to 96 h by Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) (Fig. 3). At 12 hours of Y-27632 exposure, the metabolic profiles were similar for both hESCs and hiPSCs; glucose concentration increased whereas lactate and alanine production decreased, indicating down-regulation of the glycolytic route. TCA cycle and glutaminolysis were also down-regulated. Some amino acids (glycine, proline, and GABA for both ESCs and iPSCs, and threonine, serine, phenylalanine, tyrosine for hESCs) and urea (for both cell types) were reduced. From 12 h to 24 h, the most important difference was the reduction of metabolites in the serine-glycine-threonine pathway. In addition, aspartate was reduced in both hiPSCs and hESCs. The further reduction at 24 h in the metabolite pools is more intense in hiPSCs. After 48 h of exposure time, metabolism increased as indicated by the activation of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, TCA cycle and amino acid pools (serine, glycine, threonine for both types of cells, ornithine, phenylalanine for hESCs, and aspartate, leucine, valine for hiPSCs). Overall, the metabolic behaviour of hESCs and hiPSCs was similar up to 48 h. In contrast, at 96 h only hESCs increased glycolytic rate and up-regulated the TCA cycle with increased aspartate whereas hiPSCs down-regulated glutaminolysis and aspartate production. Hence, not only was the metabolism of ROCK-exposed hPSCs different from that of the day 0 control, but cells sequentially down-regulated metabolism at 12 and 24 hours, followed by an upregulated metabolic profile at 48 hours and had completely disparate physiology by 96 hours of exposure.

Figure 3. Network representation of significant metabolic changes over time.

Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) was applied between time-points. The metabolic transitions are similar up to 48 h. 48 h to 96 h transition is different between hESCs and hiPSCs. Glycolysis, glutaminolysis and amino acid pools are up-regulated at 0 h, they reach their lower level at 24 h and they increase their activity again at 48 h. At 96 h the metabolite pools are increasing for the hESCs and decreasing for the hiPSCs.

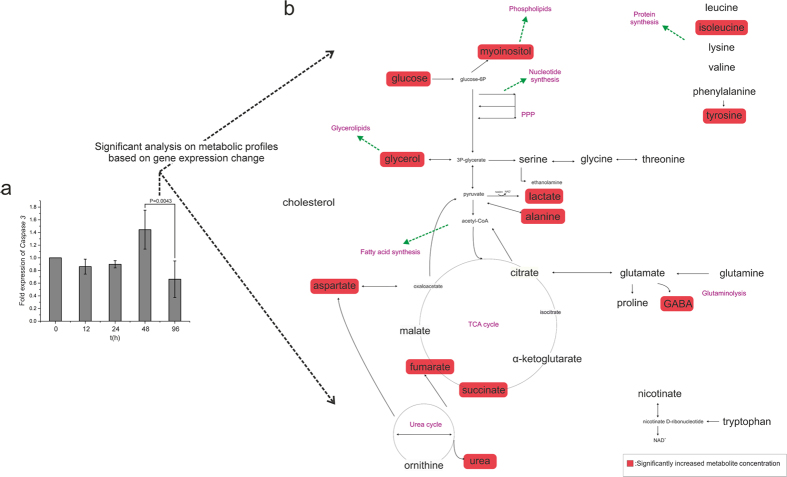

Caspase-3 expression did not differ up to 48 hours of ROCK exposure

ROCK inhibition blocks caspase-3 apoptotic signalling31,32. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that there was no change in caspase-3 expression at any time-point in the hiPSCs cultures (data not shown). In contrast, there was a significant decrease in caspase-3 expression in hESCs from 48 h to 96 h of ROCK inhibition (Fig. 4a). This alteration of caspase-3 from 48 h to 96 h may reflect on the increased activity of metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, TCA cycle, glycerolipids and phospholipids synthesis in hESCs, which is required for apoptosis33, as shown in Fig. 4b, after significant analysis and comparison of the metabolic profiles of the two time-points. Regardless, changes in metabolism observed throughout in the cultures of both hPSC types cannot be explained by changes in caspase-3 expression, which remained stable for at least 48 hours and similar to that of 0 h control unexposed cells. In all cases, the viability of the cells remained high (data not shown).

Figure 4. Caspase 3 expression over time in hESCs.

(a) Caspase 3 expression is significantly reduced at 96 h compared with that at 48 h, (p < 0.05) (expressions always relative to 0 h). (b) This effect at 96 h is highlighted by the increased metabolite pools, as expected when cells commit to apoptosis, a metabolically-demanding process.

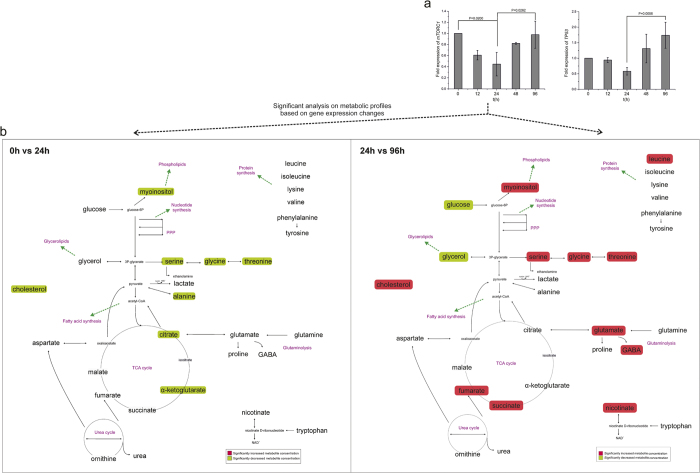

mTORC1 expression correlated with metabolic changes, independent of tp53

Expression of two major metabolic controllers, mTORC1 and tp53, was assessed. In hESC cultures inhibited by ROCK (Fig. 5), no difference in tp53 expression throughout the culture time was observed. In contrast, mTORC1 expression was lower at 24 h and 96 h exposure compared to the control 0 h unexposed cells (p < 0.05; Fig. 5a), correlating with decreased metabolic activity at the same time points (Fig. 5b), as identified by the significant analysis of the metabolic profiles between these time-points. Specifically, at 24 h glycolysis and glutaminolysis, lipid synthesis, most of the amino acid pools and TCA cycle were less active, whereas at 96 h glycolysis and glutaminolysis were reduced compared to the control 0 h unexposed group. In hiPSC cultures inhibited by ROCK (Fig. 6), expression of tp53 was higher only at 96 h exposure compared with that at 24 h exposure, coincident with the increased glycolysis and glutaminolysis, TCA cycle and lipid synthesis at 96 h exposure (Fig. 6a and b). In contrast, mTORC1 expression was lower following 24 h exposure and then increased again at 96 h exposure (p < 0.05), correlating with similar changes in metabolism. Therefore, in both hESCs and hiPSCs, decreased expression of mTORC1 correlated with reduced metabolism after 24 h of exposure with Y-27632, independent of tp53 and caspase3 expression levels.

Figure 5. Expression of mTORC1 and tp53 in hESCs exposed to ROCK inhibitor and on-network representation.

(a) mTORC1 expression is significantly reduced at 24 h and 96 h compared with that at 0 h in hESCs (p < 0.05), whereas expression of tp53 is unchanged throughout culture (expressions always relative to 0 h). (b) Reduction of mTORC1 expression correlated with significant decreases in the concentration of metabolite pools at 24 h compared to 0 h and a further decrease at 96 h. The comparisons applied were chosen accordingly to the significant changes on gene expression.

Figure 6. Expression of mTORC1 and tp53 in hiPSCs exposed to ROCK inhibitor and on-network representation.

(a) mTORC1 is less expressed at 24 h compared with that at 0 h; expression increases again at 96 h (p < 0.05). Expression of tp53 is also increased at 96 h compared with that at 24 h (p < 0.05) (expressions always relative to 0 h). (b) These changes in mTORC1 and tp53 expression are reflected in the metabolic transitions, wherein metabolite pools decreased at 24 h and increased again at 96 h. The comparisons applied were chosen accordingly to the significant changes on gene expression.

ROS/RNS levels and catalase expression suggest a correlation with proliferative metabolism

The measurement of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) indicated a reduction in ROCK inhibitor-treated hESCs throughout the culture period. In contrast, following an initial reduction of ROS/RNS at 12 h and 48 h, an increase in ROS/RNS was observed at 96 h in hiPSCs (Supplementary Figure 2). Catalase expression was also significantly increased at 96 h in hiPSCs cultures compared to 12 h, 24 h and 48 h. No significant change has been observed in glutamylcysteine synthetase (GCS) expression in both hESC and hiPSC cultures whereas a significant decrease of glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX-1) expression was observed only at 24 h in hESCs (Supplementary Figure 3).

Discussion

The use of the ROCK inhibitor on hPSCs has been shown not to affect their stemness18,25. In contrast, its effect on metabolism has not been investigated. Herein, we confirm that treatment of hiPSCs and hESCs with ROCK inhibitor does not affect the expression of pluripotency markers at gene and protein level, whereas their metabolism is altered and becomes distinctly different. The observed metabolic changes appeared to be irreversible since the cells did not revert back to the metabolic signature of untreated cells. Furthermore, the metabolic transitions, in both cell types, were similar up to 48 h of ROCK inhibitor exposure and correlated with expression levels of mTORC1 at 24 h of ROCK inhibition, but were independent of tp53 or caspase-3 expression. Finally, the detected metabolic differences between hESCs and hiPSCs indicate that although the two hPSC types share many phenotypic similarities, they are not physiologically identical suggesting that their metabolic features should be considered in designing hPSC bioprocesses to deliver robust maintenance and differentiation protocols.

The effects on metabolism could be explained by the single cell culture conditions that result in loss of cell-to-cell contact, changes to nutrient availability in single cell cultures compared to that for cells grown within colonies, and the time-period required for cells to adapt to an environment conducive to single cell culture. hPSCs are highly proliferative cells and share metabolic characteristics with cancer cells5,26,27. In tumors, the glycolytic rate is reduced when E-cadherin is unbound34 similar to what we observed when the 0 h-untreated cells cultured in colonies were compared with treated cells at other time-points. After 12 h and 24 h of exposure to ROCK inhibitor, the metabolism of both hESCs and hiPSCs was down-regulated, less glycolytic and, therefore, less proliferative. According to literature on mammalian signalling, an indirect connection between ROCK and mTORC1 exists. ROCK inhibition has been shown to dramatically suppress phosphorylation and activity of FAK (Focal Adhesion Kinase)35,36. FAK activation has also been correlated with increased proliferation via regulation of the Akt/mTORC1 pathway37. Recently, this relationship was demonstrated at the metabolic level, where FAK activation increased glycolytic metabolism (aerobic glycolysis), which substituted mitochondrial respiration38. Consequently, ROCK inhibition could lead to down regulated FAK activity followed by suppressed mTORC1 signaling and a decreased proliferative (glycolytic) metabolism, which is in agreement with our results, as early as 12 h.

The serine-glycine-threonine pathway is directly connected to one-carbon metabolism, which is the folate and methionine cycle, as independent modules. One-carbon metabolism cycles carbon units, amino acids, to maintain redox balance and promote biosynthesis. Folate cycle activation is a sign of nucleic acid biosynthesis39, among others. Studies in cancer metabolism have suggested that pathway activation is correlated with proliferation of cells40,41. Serine biosynthesis and glycine metabolism promote tumorigenesis41. Our results show that the serine-glycine-threonine pathway is down-regulated following 12 h and 24 h exposure and up-regulated after 48 h exposure for both hESCs and hiPSCs (Fig. 3). Overall, it is clear that the cells lose their highly proliferative physiology after the exposure to ROCK inhibitor and the dissociation into single cells as indicated by their metabolic profiles and the metabolic pathways affected. Their metabolic physiology never returned to the initial condition.

Metabolic transitions following 48 h exposure to ROCK inhibitor were similar for both hESCs and hiPSCs. In contrast, 96 h exposure resulted in divergent metabolism for the two cell types. In hESCs metabolism increased; in contrast, hiPSCs had decreased metabolic activity. hESCs and hiPSCs share similar but not identical metabolism26. This fact could explain why the same manipulation (i.e. dissociation of colonies and exposure to Y-27632) could cause different effect(s), especially when the treatment is prolonged, as was observed following 96 h exposure ROCK inhibitor. Both hESCs and hiPSCs reduced their metabolic activity trying to adapt to the new environment, something which is clear from the12 h and 24 h metabolic profiles. After 48 h exposure, the cells appear to finally adapt to the new environment and increase their metabolic activity again, assuming a more proliferative metabolism. The two cell types follow discrete directions afterwards. Moreover, even if gene and protein expression of pluripotency markers remained high following 96 h exposure to ROCK inhibitor, a small but significant decrease in the percentage of pluripotent cells was observed. This could explain the divergent effects on the metabolism between the two types of cells after 96 h of exposure, where hESCs increase their metabolite pools further while hiPSCs show a decrease in their metabolic activity when compared to 48 h exposure. It becomes clear that hESCs respond differentially to the prolonged exposure to ROCK inhibitor and single cultivation than hiPSCs.

Both hESCs and hiPSCs encounter a critical point in culture at 24 h of exposure, as indicated by the metabolic change commensurate with reduction in mTORC1. It has been shown that metabolism plays a significant role in defining human pluripotent stem cell fate, mostly by affecting the epigenome, in an irreversible way following a critical point5,42,43. Increased mTORC1 expression favors growth metabolism, i.e. increased glycolysis and glutaminolysis, whereas the opposite effect is expected when mTORC1 is not expressed. Interestingly, tp53 expression is also increased at 96 h compared to 24 h in hiPSCs – this may represent an attempt of cells to control proliferative activity. High mTORC1 expression44 induces tp53, as the two proteins counter-balance each other45,46, with mTORC1 favoring growth when environmental conditions (nutrients, O2, etc.) are appropriate47, while tp53 suppresses growth and proliferation when necessary28,29,48. ROCK inhibition blocks the pathway of myosin II to caspase-induced apoptosis49. In hESCs, caspase-3 expression decreased after 96 h exposure but not at 48 h exposure, coincident with activation of the glycolysis pathway at 96 h with respect to production of glycerolipids and phospholipids, consistent with previous work that showed that caspase-driven apoptosis is metabolically demanding33.

ROS/RNS and catalase expression analyses indicate a positive correlation between proliferative metabolism and oxidative stress. The decrease in ROS/RNS levels in hESCs is followed by a decrease in mTORC1 expression, while the increase in ROS/RNS levels and catalase expression at 96 h at hiPSCs cultures correlates with a more proliferative metabolism and increased mTORC1 expression. Our results are in agreement with the literature. Specifically, a positive relationship between pluripotency and hPSC maintenance with proliferative metabolism and reduction of ROS50 has already been established. Similarly, ROCK inhibition has been linked to down-regulation of oxidative stress51.

Metabolism represents the cellular function that is most sensitive to even small environmental disturbances; GC-MS metabolomics has already been proven sensitive enough to detect changes in the physiology of cell cultures compared to gene and protein expression52, something of great value in the fields of stem cell biology and cell culture engineering in terms of monitoring and bioprocess optimization. Ultimately, metabolomics could be used as a release assay for verifying both product (cells) and bioprocess quality.

In conclusion, exposure to ROCK inhibitor altered cellular metabolism whereas gene and protein expression of pluripotency markers remained unaffected; as early as 12 h exposure to ROCK inhibitor resulted in the metabolism of both hESCs and hiPSCs being different than that of unexposed cells. Generally, hPSC metabolism decreased for the first 24 h of exposure and then increased again at 48 h exposure for both hESCs and hiPSCs, with completely disparate metabolic pathways followed following 96 h exposure. The observed metabolic changes correlated well with similar changes in mTORC1 expression, a principal metabolic regulator, yet were independent of tp53 and caspase-3 expression levels. Our findings indicate that metabolomics is essential in deciphering changes of physiology and is an invaluable tool in the field of stem cell bioprocessing as it can be used to identify optimal physiological transitions and result in robust cultivation processes.

Methods

Cell Cultures

The pluripotent stem cell lines, hESCs (WA09) and hiPSCs (MR90-1) from WiCell Research Institute, WI, USA were used at passages 29 to 33. Cells were cultured in mTeSR1 (STEMCELL Technologies Canada Inc., Vancouver, BC) in Matrigel Matrix (Corning, NY, US) as recommended by the manufacturer. The hESCs and hiPSCs were either treated with 10 μM of Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor or not. Samples were collected at different time-points, 0-untreated, 12, 24, 48, 96 hours (h) and tested over the expression of pluripotency markers (Fig. 1A). The earliest time point that meaningful analysis could be performed is 12 h as the single cells need sufficient time to attach to the culture surface. Samples treated with ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) where cultured in mTeSR1 with 10 μΜ Y-27632 (dihydrochloride - Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) for 2 hours. Thereafter, cells were detached with the use of Accutase (StemPro - Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), colonies were dissociated into single cells by pipetting22,23,24, seeded at 30–40 * 104 cells/cm2 density on Matrigel and cultured in mTeSR1 with 10 μΜ Y-27632 up to 96 h. Samples from three independent experiments (N = 3) were collected.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from hESCs and hiPSCs was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN Sciences, MD, USA). The primers used were: sox2 F-5′-GCCGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCG-3′, R-5′-GCAGCGTGTACTTATCCTTCTT-3′ 53, oct4 F-5′-GTTGATCCTCGGACCTGGCTA-3′ R-5′-GGTTGCCTCTCACTCGGTTCT-3′ 53, nanog F-5′-GTCTTCTGCTGAGATGCCTCACA-3′ R-5′-CTTCTGCGTCACACCATTGCTAT-3′ 53, caspase3 F-5′-AATTGTGGAATTGATGCGTGATG-3′ R-5′-CTACAACGATCCCCTCTGAAAAA-3′ 54, tp53 F-5′-CCAGGGCAGCTACGGTTTC-3′ R-5′-CTCCGTCATGTGCTGTGACTG-3′ 55, mtorc1 F-5′-CTGGGACTCAAATGTGTGCAGTTC-3′ R-5′-GAACAATAGGGTGAATGATCCGGG-3′ 56, gapdh F-5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ R-5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ 56, F-5′-CCTTCTGGCACAGCACGTTG-3′ R-5′-TAAGACGGCATCTCGCTCCT-3′ gcs57, F-5′-CCTCAAGTACGTCCGACCTG-3 R-5′-CAATGTCGTTGCGGCACACC-3′ gpx-160, F-5′-GCAGATACCTGTGAACTGTC-3′ R-5′-GTAGAATGTCCGCACCTGAG-3′ catalase57. One-step cDNA synthesis and PCR analysis was applied, using the KAPA SYBR FAST ABI Prism One-Step qRT-PCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, Inc. MA, US). Relative quantification was obtained measuring SYBR Green I fluorescence (ROX reference dye) with the StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems - Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) qPCR instrument. Per reaction, 1 ng of RNA was used.

Metabolite profiling

Cells were washed twice with PBS before cold methanol (−40 °C) was added to culture plates (6-well - Corning, NY, US). At least 106 cells were extracted from each replicate-sample of hPSCs using ribitol (1 mg/1 × 106 cells) as an internal standard, as previously described52. The process of methoximation (50 μL of 20 mg methoxyamine hydrochloride/mL pyridine) and MSTFA (100 μL of N-methyl-trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide) derivatization turned the dried polar extracts into their (MeOx) TMS-derivatives58,59. Metabolic profiles were obtained using QP2010 Ultra GC-MS and GCMSsolution software Ver.4.11 (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). The raw metabolomics dataset was comprised of 84 peaks of known chemical category metabolites. From each independent sample, three experimental replicates (n = 3) were created. The relative peak areas of all detected peaks (RPAs) were estimated from their normalization with the 103 marker ion peak area of the internal standard ribitol. Data normalization and filtering are applied before incorporation into the final dataset table58,59. Cumulative (effective) peak areas were calculated using weight coefficients of the hESCs 0 h-untreated cells. All analyses applied on the acquired metabolic profiles were based on standardized values of the metabolite relative peak areas52.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were assessed for both intracellular and extracellular markers of pluripotency. After fixation and permeabilization for intracellular marker expression, cells were stained with –phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Mouse anti-Human Nanog (Clone N31-355), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated Mouse anti-Oct3/4 (Clone 40/Oct3) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Mouse anti-Sox2 (Clone 245610) (BD Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Transcription Factor Analysis Kit). For extracellular marker expression, cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated -Rat anti-SSEA-3 (Clone MC631) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Mouse anti-Human TRA-1-81 (Clone TRA-1-81) (BD StemFlow Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Sorting and Analysis Kit). Isotypes controls used were phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Rat IgM (R4-22), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Mouse IgM (G155-228), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Mouse IgG (MOPC-21), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated Mouse IgG (X40), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Mouse IgG2a (MOPC-173). In all cases, cells were collected with the use of Accutase and counted using a standard haemocytometer. All antibodies were used at a concentration of 20 μL/sample obtained from BD Biosciences (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was the instrument used for the analyses and 10000 events were analysed for each sample. FlowJo 10.1 (FlowJo LLC, OR, USA) software was used for the data analyses.

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used for flow cytometry and qRT-PCR data comparison (N = 3, n = 3). The level of statistical significance was set by p < 0.05. The p-values where differences were significant are clearly noted on the figures. Unsupervised HCL and PCA algorithms were used as visualization methods of the differences among samples, based on their metabolic profiles (N = 3, n = 3). The Euclidean distance metric was used in HCL. SAM was used to identify the metabolites, whose concentration was significantly higher or lower in a set of metabolic profiles compared to another, with false discovery rate (FDR) at zero60. TM4 MeV v4.9.1 (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, MA) was used for the multivariate61 and Origin2016 (OriginLab Corporation, MA) for univariate statistical analyses.

Immunocytochemistry

Sox2 and Oct4 protein expression was assessed using immunofluorescence. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde solution in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and subsequently blocked with a PBS solution of 10% (v/v) normal donkey serum, 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100 and 1% (w/v) BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) for 45 min at room temperature in order to avoid non-specific antibody binding. After blocking, the cells were incubated for 3 h with conjugated antibodies at 1:10 dilution (NL557 PE-conjugated Goat Anti-Human SOX2, NL637 Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Goat Anti-Human Oct-4) (R&D Systems Inc, MN) at room temperature and counterstained with DAPI for 5 min. Images were taken with a BX-51 Olympus microscope (Olympus, UK).

ROS/RNS assay

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) levels were evaluted with the use of quenched fluorogenic probe dichlorodihydrofluorescin (DCFH-DiOxyQ; OxiSelect, Cell Biolabs, CA). Cells were resuspendend at a cell density of 1 × 107 cells/mL in PBS and lysed with 1% (w/v) Triton X-100 solution and spinned at 10000 g for 5 min to remove insoluble particles. They were assayed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Vernardis, S. I. et al. Human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells maintain phenotype but alter their metabolism after exposure to ROCK inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 7, 42138; doi: 10.1038/srep42138 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an EU FP7 project grant, AmbuLung (project reference 304932), awarded to AM.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions S.I.V. and A.M. designed the experiments, S.I.V. performed the experiments and the data analysis, K.T. assisted on the experiments and performed part of the data analysis, N.P., S.I.V. and A.M. wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Takahashi K. et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placzek M. R. et al. Stem cell bioprocessing: fundamentals and principles. J R Soc Interface 6, 209–232, doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0442 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilic J. & Izpisua Belmonte J. C. Concise review: Induced pluripotent stem cells versus embryonic stem cells: close enough or yet too far apart? Stem Cells 30, 33–41, doi: 10.1002/stem.700 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K. & Suda T. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 243–256, doi: 10.1038/nrm3772 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber H. et al. The metabolome regulates the epigenetic landscape during naive-to-primed human embryonic stem cell transition. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1523–1535, doi: 10.1038/ncb3264 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida Y. S. et al. ERRs Mediate a Metabolic Switch Required for Somatic Cell Reprogramming to Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 16, 547–555, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw S. L., Min-Wen C., Koh C. G., Lim B. & Shyh-Chang N. Oocyte Factors Suppress Mitochondrial Polynucleotide Phosphorylase to Remodel the Metabolome and Enhance Reprogramming. Cell Rep 12, 1080–1088, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.032 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmes C. D., Dzeja P. P., Nelson T. J. & Terzic A. Mitochondria in control of cell fate. Circ Res 110, 526–529, doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e31824ae5c1 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit M. et al. Clonally derived human embryonic stem cell lines maintain pluripotency and proliferative potential for prolonged periods of culture. Dev Biol 227, 271–278, doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K., Fujioka T., Nakamura Y., Nakatsuji N. & Suemori H. A method for the selection of human embryonic stem cell sublines with high replating efficiency after single-cell dissociation. Stem Cells 24, 2649–2660, doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0657 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K. et al. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 25, 681–686, doi: 10.1038/nbt1310 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson M. F. Applications for ROCK kinase inhibition. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20, 242–248, doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.002 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S. M. et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol 27, 275–280, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wataya T. et al. Minimization of exogenous signals in ES cell culture induces rostral hypothalamic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 11796–11801, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803078105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharvand H., Salekdeh G. H., Taei A. & Mollamohammadi S. An efficient and easy-to-use cryopreservation protocol for human ES and iPS cells. Nat Protoc 5, 588–594, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.247 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Meng G., Krawetz R., Liu S. & Rancourt D. E. The ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 enhances the survival rate of human embryonic stem cells following cryopreservation. Stem Cells Dev 17, 1079–1085, doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0247 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre N. et al. The ROCK Inhibitor Y-27632 Improves Recovery of Human Embryonic Stem Cells after Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting with Multiple Cell Surface Markers. PloS one 5, doi: ARTN e12148 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgushi M. et al. Molecular pathway and cell state responsible for dissociation-induced apoptosis in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 225–239, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.018 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. K., Hou Z. G., Gulbranson D. R. & Thomson J. A. Actin-Myosin Contractility Is Responsible for the Reduced Viability of Dissociated Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 240–248, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.017 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A. et al. Non-muscle myosin II regulates survival threshold of pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun 1, doi: ARTN 71 10.1038/ncomms1074 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T. et al. Pharmacological properties of Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of rho-associated kinases. Mol Pharmacol 57, 976–983 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T. et al. Laminin E8 fragments support efficient adhesion and expansion of dissociated human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun 3, 1236, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollamohammadi S. et al. A simple and efficient cryopreservation method for feeder-free dissociated human induced pluripotent stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Hum Reprod 24, 2468–2476, doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep244 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara M. et al. Manipulation of a VEGF-Notch signaling circuit drives formation of functional vascular endothelial progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res 24, 820–841, doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.59 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthaman K., Fong C. Y. & Bongso A. Effect of ROCK Inhibitor Y-27632 on Normal and Variant Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs) In Vitro: Its Benefits in hESC Expansion. Stem Cell Rev Rep 6, 86–95, doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9107-8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panopoulos A. D. et al. The metabolome of induced pluripotent stem cells reveals metabolic changes occurring in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Res 22, 168–177, doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.177 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissen J. K. et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Show Metabolomic Differences to Embryonic Stem Cells in Polyunsaturated Phosphatidylcholines and Primary Metabolism. PloS one 7, doi: ARTN e4677010.1371/journal.pone.0046770 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks O. D. K. et al. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 493, 542-+, doi: 10.1038/nature11743 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. G. et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell 18, 283–293, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibble C. C. & Manning B. D. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol 15, 555–564 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T. et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265, doi: 10.1038/nature07935 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura N. et al. Enhancement on primate corneal endothelial cell survival in vitro by a ROCK inhibitor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 3680–3687, doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2634 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradelli L. A., Villa E., Zunino B., Marchetti S. & Ricci J. E. Glucose metabolism is inhibited by caspases upon the induction of apoptosis. Cell Death & Disease 5, doi: ARTN e140610.1038/cddis.2014.371 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K., Boley K. M., Moraes R., Barsky S. H. & Robertson F. M. The paradox of E-cadherin: role in response to hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and regulation of energy metabolism. Oncotarget 4, 446–462, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.872 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsoni A. S., Marin T. M., Velloso L. A. & Franchini K. G. RhoA/ROCK signaling is critical to FAK activation by cyclic stretch in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol-Heart C 289, H1488–H1496, doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00692.2004 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidou G. et al. RHOA-FAK Is a Required Signaling Axis for the Maintenance of KRAS-Driven Lung Adenocarcinomas. Cancer Discov 3, 444–457, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-12-0388 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton G. H. et al. Focal Adhesion Kinase Is Required for Intestinal Regeneration and Tumorigenesis Downstream of Wnt/c-Myc Signaling. Dev Cell 19, 259–269, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.015 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Focal adhesion kinase-promoted tumor glucose metabolism is associated with a shift of mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis. Oncogene 35, 1926–1942, doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.256 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X., Zhao F. & Thompson C. B. The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19, 32–37, doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.002 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M. et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science 336, 1040–1044, doi: 10.1126/science.1218595 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreekumar A. et al. Metabolomic profiles delineate potential role for sarcosine in prostate cancer progression. Nature 457, 910–914, doi: 10.1038/nature07762 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Yanes O. et al. Metabolic oxidation regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nat Chem Biol 6, 411–417, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.364 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey B. W., Finley L. W., Cross J. R., Allis C. D. & Thompson C. B. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 518, 413–416, doi: 10.1038/nature13981 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H. et al. Constitutive mTOR activation in TSC mutants sensitizes cells to energy starvation and genomic damage via p53. EMBO J 26, 4812–4823, doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601900 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Zhang H., Levine A. J. & Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 8204–8209, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. p53 regulation of the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR pathways and the endosomal compartment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2, a001057, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001057 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Peterson T. R. & Sabatini D. M. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol Cell 40, 310–322, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R. et al. p53-dependent regulation of autophagy protein LC3 supports cancer cell survival under prolonged starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 18511–18516, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006124107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G., Niso-Santano M., Baehrecke E. H. & Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 81–94, doi: 10.1038/nrm3735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S., Lindgren A. G., Srivastava A. S., Clark A. T. & Banerjee U. Mitochondrial function controls proliferation and early differentiation potential of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 29, 486–495, doi: 10.1002/stem.590 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma K. et al. Roles of rho-associated kinase and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of aortic stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol 49, 698–705, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.082 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernardis S. I., Goudar C. T. & Klapa M. I. Metabolic profiling reveals that time related physiological changes in mammalian cell perfusion cultures are bioreactor scale independent. Metab Eng 19, 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.04.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page R. L. et al. Induction of stem cell gene expression in adult human fibroblasts without transgenes. Cloning Stem Cells 11, 417–426, doi: 10.1089/clo.2009.0015 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motevaseli E. et al. Normal and tumour cervical cells respond differently to vaginal lactobacilli, independent of pH and lactate. J Med Microbiol 62, 1065–1072, doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.057521-0 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Niu D., Lai L. & Ren E. C. p53 increases MHC class I expression by upregulating the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase ERAP1. Nat Commun 4, 2359, doi: 10.1038/ncomms3359 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal P. et al. Baicalein induces autophagic cell death through AMPK/ULK1 activation and downregulation of mTORC1 complex components in human cancer cells. Febs J 281, 4644–4658, doi: 10.1111/febs.12969 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mouatassim S., Guerin P. & Menezo Y. Expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes in human and mouse oocytes during the final stages of maturation. Mol Hum Reprod 5, 720–725 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanani H. H. & Klapa M. I. Data correction strategy for metabolomics analysis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Metab Eng 9, 39–51, doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.08.001 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanani H., Chrysanthopoulos P. K. & Klapa M. I. Standardizing GC-MS metabolomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 871, 191–201, doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.04.049 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R. & Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 5116–5121, doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I. et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol 411, 134–193, doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.