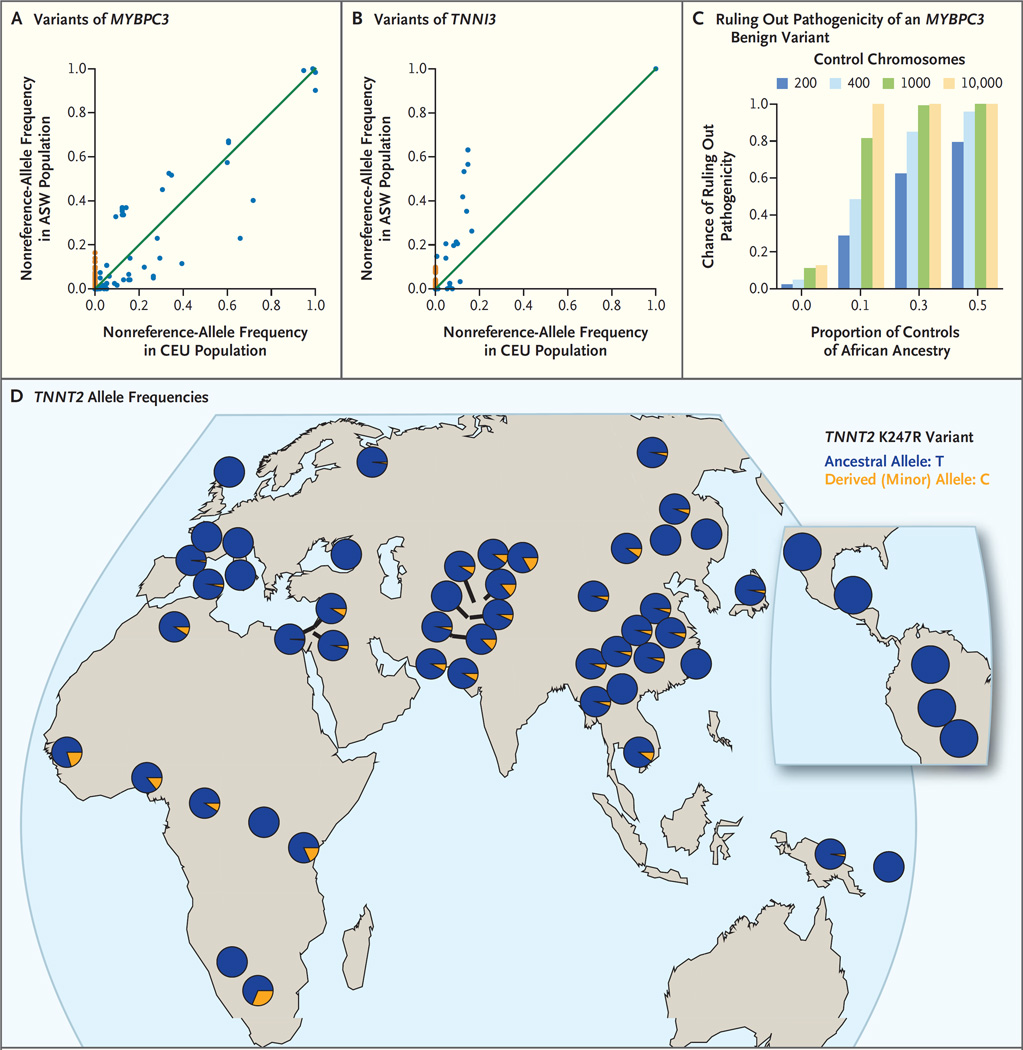

Figure 2. Prevention of Misclassification of Variants with the Use of Data from Diverse Populations.

Panels A and B show frequencies of the nonreference allele (i.e., the allele that is not present in the reference sequence of the human genome) for the 1000 Genome Project populations ASW (African Ancestry in Southwest USA) (61 persons) and CEU (Utah Residents [CEPH] with Northern and Western European ancestry) (85 persons) for the genes MYBPC3 (Panel A) and TNNI3 (Panel B). Each point represents a distinct variant. There are significantly more private sites (sites for which the nonreference-allele frequency is nonzero in one population but zero in the other population) among black Americans (nonreference-allele frequency, 0% in CEU and >0% in ASW, with ASW private sites shown in orange) than among white Americans (nonreference-allele frequency, 0% in ASW and >0% in CEU). Panel C shows the chance of correctly ruling out pathogenicity for a truly benign variant that is found predominantly in one ancestry group; the probability generally increases with the fraction of the control cohort that is made up of that ancestry group and with the number of controls (numbers of control chromosomes are shown in the key). These simulations use the allele frequencies of the MYBPC3 G278E variant, which has a minor-allele frequency of 0.0157 among black Americans and 0.000122 among white Americans. Panel D shows a map of TNNT2 allele frequencies; the K247R variant of TNNT2 (rs3730238 in dbSNP) was genotyped in the Human Genome Diversity Project. Most populations around the world have a nonzero minor-allele frequency.