Abstract

The relationship between soccer and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is not well established. Clinicopathological correlation in an 83-year-old retired center-back soccer player, with no history of concussion, manifesting typical Alzheimer-type dementia. Examination revealed mixed pathology including widespread CTE, moderate Alzheimer’s disease, hippocampal sclerosis, and TDP-43 proteinopathy. This case adds to a few CTE cases described in soccer players. Furthermore, it corroborates that CTE may present clinically as typical Alzheimer-type dementia. Further studies investigating the extent to which soccer is a risk for CTE are needed.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, humans, soccer, autopsy, Chronic Post-Traumatic Encephalopathy, dementia

First recognized in boxers as a late complication of repeated head injury, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has received more attention following a series of high-profile cases in former football players. Albeit somewhat different than in boxers, these football players exhibited progressive erratic, impulsive, and aggressive behavior usually in their fourth and fifth decades of life, as well as underlying tauopathy. Further evidence showed that CTE presents in a broader setting including military service and other contact sports, including hockey and professional wrestling [1]. Soccer is the most popular sport worldwide with over 250 million players at all levels. Soccer is a limited-contact sport although trauma to the head is not uncommon, being ranked second after trauma to the thigh in the last World Cup [2]. Clinical studies report discrepant results concerning changes in brain function and structure in active and former soccer players exposed to headings [3–8]. To date, CTE pathology was described in two soccer players [1, 9]. We describe a case of CTE presenting typical symptoms of late-onset Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) in a former soccer player.

Case Description

A 79-year-old retired soccer player presented to our clinic with severe dementia. He played as a professional center-back for 21 years, reaching the status of the captain of the Brazilian team, and retired at age 39 [10]. Twelve years prior (age 67), he began to develop short-term memory problems, starting with a failure to memorize a text for a TV advertisement and including repeating sentences. At age 68, he became forgetful of money withdraws. At age 69, he was diagnosed formally with AD by a neurologist. He had no insight into his condition and denied any memory problem. At age 72, a neuropsychological evaluation detected severe impairment of delayed recall tests both for verbal and visual items, and for naming objects together, with moderate impairment of verbal fluency and visual perception, endorsing a diagnosis of probable AD. Episodes of random shouting spells starting at age 79 prompted referral to our service. At this time, he was under treatment of mild arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, both of which were under control, and he was receiving galantamine and memantine. He had no history of concussion, severe head injury, loss of consciousness, alcoholism, or drug abuse. He had 11 siblings, five of which reached adult life. One sister had late-onset dementia diagnosed as AD.

The exam revealed severe dementia and a slower, but uncharacteristic gait. The shouting spells disappeared completely after treatment with risperidone 0.5 mg/day. A CT scan obtained after the visit revealed temporal atrophy, a small old right frontal cortico-subcortical infarct, white matter hypoattenuation, and sporadic lacunes. He died at the age of 83, 16 years after the onset, bedridden and fed by gastrostomy. During the disease, he never manifested hallucinations, convulsions, or behavioral disturbances.

The postmortem brain was scanned in a 3T MRI after fixation. Radiological examination (Fig. 1) and gross examination (Fig. 2A) showed prefrontal, middle frontal gyrus, anterior and mesial temporal and anterior cingulate cortex atrophy, greater on the left, bilateral atrophy of the hypothalamus and fornices with pronounced volume reduction of the mammillary bodies, and a post-ischemic lesion in the right frontal lobe. Furthermore, the brain showed a cavum septum pellucidum and few lacunae in basal ganglia, thalamus, and pons. The locus ceruleus and substantia nigra were pale. Microscopic assessment (Fig. 3) was consistent with the most severe stage of CTE (stage IV) [11], featuring phospho-tau deposition, more intense in the depths of cortical sulci with a clear perivascular distribution. The superficial cortical layers displayed a higher burden of neuronal and thorny glial inclusions than the deep layers. Phospho-tau positive CTE pathology was widespread throughout the limbic and inferior temporal cortices and subcortical structures, including amygdala, thalamus, and brainstem. Mild to moderate CTE pathology was observed in middle frontal, superior temporal, pre-central and angular gyrus. The CTE-like tau inclusions were positive for 3-repeat-, 4-repeat, and acetylated tau. The neocortex and hippocampus showed neuritic plaques. No neuritic plaques were observed elsewhere, including putamen, brainstem, and cerebellum. The distribution of beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles warranted a diagnosis of intermediate AD neuropathological changes - A1,B2,C3 [12]. Finally, the hippocampus exhibited severe sclerosis (Fig. 2). The sclerotic area featured TDP-43 positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions and gray matter threads. TDP-43 proteinopathy was also observed in other limbic areas, including anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala, and to a lesser extent, inferior temporal cortex and middle frontal gyrus (Fig. 2). TDP43-proteinopathy consisted of dense TDP-43-positive rounded and crescentic neuronal cytoplasmic and glial inclusions and threadlike neurites. In cortical areas, TDP-43 inclusions were observed in all cortical layers and white matter. The brain was free of α-synuclein inclusions. APOE genotype was ε3/ε3.

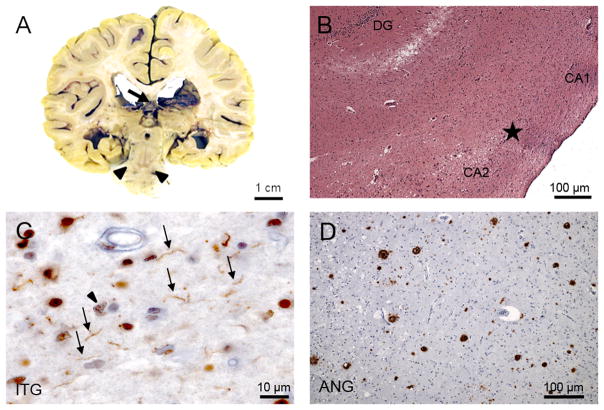

Figure 1.

Radiological features of the case. A) Non-contrast axial CT: the arrow points to hypoattenuation in periventricular white matter region and infarct in the right middle frontal gyrus (arrow). B) and C) Axial formalin fixed post-mortem MR T1-weighted images showing the infarct (arrow in B) and lacunae in the basal ganglia (arrows in C). D) Frontal and E) superior views from 3D renderings from the postmortem MR images showing atrophic changes in frontal and temporal areas (arrows). F) Coronal formalin fixed post-mortem MR T1-weighted images showing a marked reduction of the mesial temporal and hypothalamic structures.

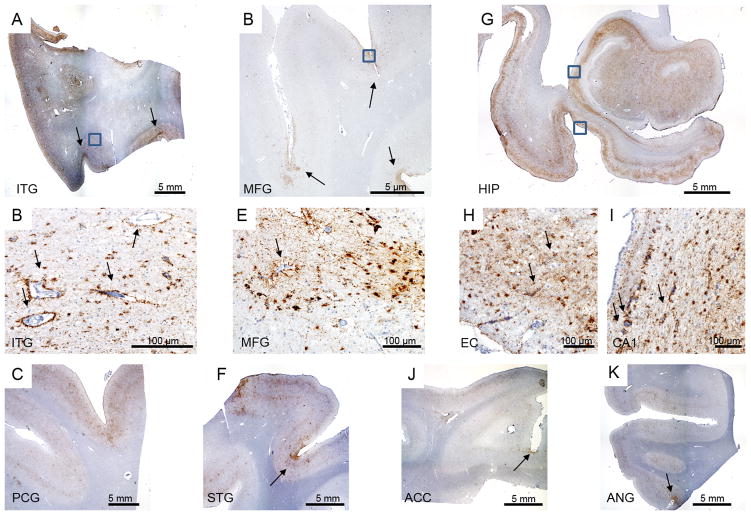

Figure 2.

Neuropathological features. A) Coronal brain slab showing a cavum septum pellucidum (arrow) and pallor of the substantia nigra (arrowhead). B) Hippocampal sclerosis. Hippocampus at the transition (star) between CA1 and CA2 sectors. Note that the neuronal strip, clearly visible on CA2 is interrupted and replaced by gliosis. H&E staining. C) Inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) immunostained for TDP-43 (TDP-43, 1:500, Proteintech) showing gray matter threads (arrows) and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (arrowhead). D) Histological section across the angular gyrus (ANG) immunostained for beta-amyloid (4G8, 1:10000, Signet Pathology Systems) depicting a moderate number of neuritic plaques.

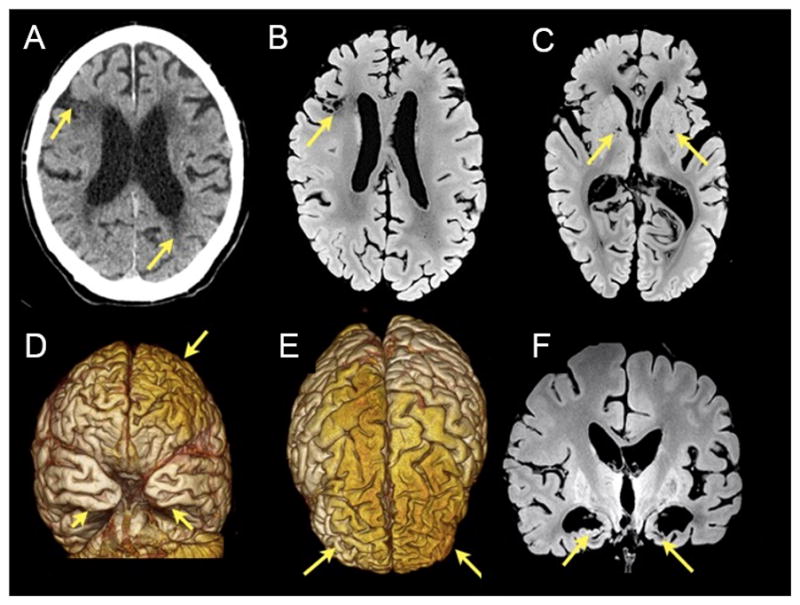

Figure 3.

CTE pathology. A) Inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) depicting widespread tau pathology, more concentrated in the superficial cortical layers and depth of the sulci (arrows). B) Enlargement of the boxed area on (A) highlighting the predominately glial pathology and perivascular tau pathology (arrows). C) Widespread tau pathology in precentral gyrus (PCG). D) Middle frontal gyrus showing tau pathology especially at the depth of the sulci (arrow). E) Enlargement of the boxed area on (D) depicting tau glial and neuronal pathology and perivascular tau deposits (arrow). F) Tau pathology in superior temporal gyrus (STG), more prominent in the depths of the sulcus (arrow). G) Hippocampal formation showing widespread tau pathology. Using this staining, it is possible to observe the thinning of the CA1 sector and subiculum. H) Enlargement over the entorhinal cortex (bottom box on G) again showing a predominant glial tau pathology and perivascular tau deposits (arrow). I) Enlargement over the CA1 sector (top box on G) highlighting the perivascular tau pathology (arrow). J and I) Tau pathology more prominent in the depth of the sulcus (arrows) in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and angular gyrus (ANG), respectively. All histological sections were immunostained for phospho-tau (CP13, 1:500, gift of Peter Davies).

Discussion

We presented a case of an older retired professional soccer player showing typical clinical features of late-onset AD with mixed neuropathological findings including severe CTE, moderate AD, hippocampal sclerosis, and TDP-43 proteinopathy. This case adds to a few CTE cases described in soccer players - a 29-year-old player with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and a 77-year-old retired player with Alzheimer-type dementia [1, 9] - corroborating that soccer may be a potential risk factor for CTE. Despite the lack of a history of concussion, subconcussive accidents are not uncommon in soccer due to collisions with other players [13]. It is noteworthy that this patient played in center-back position, where heading to the ball is common. Some studies associate headings with structural brain changes [4, 6], although this is still a controversial issue beyond the scope of this work.

In addition, this case adds to a few but growing number of reports suggesting that CTE pathology may manifest clinically as typical Alzheimer-type dementia, lacking the behavior/mood changes classically associated with CTE described in younger athletes involved in contact sports [1, 14]. CTE associated with amnestic presentation correlates with milder repetitive traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and a longer interval between the TBI episodes and the onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms [15–17]. Also, it is plausible that differences in the biomechanics involved in the TBI may result in distinctive clinicopathological pictures [1, 18].

Clarifying the exact role of CTE pathology to the cognitive decline of these older patients is complicated by the presence of other proteinopathies, as illustrated in this case. This patient met all the required and supportive neuropathological criteria for CTE (perivascular foci of p-tau lesions in the neocortex, irregular distribution of p-tau lesions at the depths of cerebral sulci, cortical NFTs located preferentially in the superficial layers, most pronounced in temporal cortex, and clusters of subpial astroglial tauopathy in the cerebral cortex, most pronounced at the sulcal depths), and showed advanced pathology [11]. Nevertheless, it is not possible to rule out that the clinical picture was a reflex of the other findings. AD pathology and hippocampal sclerosis with TDP-43 proteinopathy also manifest with an amnestic syndrome. Although the degree of AD pathology was arguably modest to justify the severe degree of dementia developed by this patient, the combination of several neurodegenerative conditions could have the sufficient synergic effect to produce severe dementia. Multiple rather than single brain pathology underlying dementia in older individuals is the rule rather than the exception [19], and CTE may be one of these diseases, as shown by this case. Evidence suggests that TBI possibly triggers and accelerates TDP-43 proteinopathy and even deposits of amyloid-beta plaques [20, 21]. It is yet to be determined if AD-type pathology and TDP-43 proteinopathy are overlapping conditions or are part of a CTE clinicopathological entity in older adults exposed to remote TBIs [18]. Regardless, TDP-43 proteinopathy is often present in subjects meeting criteria for CTE and its severity increases in CTE higher stages [20]. Hippocampal sclerosis also frequently co-occurs with CTE tau-related changes [22], although hippocampal sclerosis of the aging is recognized as a distinctive entity manifesting as amnestic cognitive decline and cannot be ruled out in this case [23, 24]. The advent of the neuropathological criteria for CTE [11] will greatly assist in recognizing the tau-related CTE component in cases of overlapping neurodegenerative conditions.

Studies to underscore how frequently CTE pathology underlies amnestic dementia and to determine the populations at risk are critical. Soccer is the most popular sport worldwide attracting millions of amateur players, including children. Evidence of CTE in professional soccer players urges for further careful studies investigating the extent to which soccer is a risk for CTE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s family for the brain donation and the Brazilian Brain Bank. We also thank Dr. Custodio M. Ribeiro for his help during patient’s terminal illness, and Dr. Daniel Perl and Dr. Ann McKee for reviewing the neuropathological slides. LTG is supported by institutional grants NIH P01-AG1972403 and P50-AG023501. This study received funding from LIM-22, University of Sao Paulo Medical School.

References

- 1.McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:29–51. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Junge A, Dvorak J. Football injuries during the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:599–602. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koerte IK, Mayinger M, Muehlmann M, Kaufmann D, Lin AP, Steffinger D, Fisch B, Rauchmann BS, Immler S, Karch S, Heinen FR, Ertl-Wagner B, Reiser M, Stern RA, Zafonte R, Shenton ME. Cortical thinning in former professional soccer players. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, Kim M, Stewart WF, Branch CA, Lipton RB. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology. 2013;268:850–857. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zetterberg H, Jonsson M, Rasulzada A, Popa C, Styrud E, Hietala MA, Rosengren L, Wallin A, Blennow K. No neurochemical evidence for brain injury caused by heading in soccer. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:574–577. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.037143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiotta AM, Bartsch AJ, Benzel EC. Heading in soccer: dangerous play? Neurosurgery. 2012;70:1–11. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31823021b2. discussion 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang MR, Red SD, Lin AH, Patel SS, Sereno AB. Evidence of cognitive dysfunction after soccer playing with ball heading using a novel tablet-based approach. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matser JT, Kessels AGH, Jordan BD, Lezak MD, Troost J. Chronic traumatic brain injury in professional soccer players. Neurology. 1998;51:791–796. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hales C, Neill S, Gearing M, Cooper D, Glass J, Lah J. Late-stage CTE pathology in a retired soccer player with dementia. Neurology. 2014;83:2307–2309. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellini G. Bellini: o primeiro capitão campeão [Bellini: the first captain champion] Prata Editora; Sao Paulo: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, Litvan I, Perl DP, Stein TD, Vonsattel JP, Stewart W, Tripodis Y, Crary JF, Bieniek KF, Dams-O’Connor K, Alvarez VE, Gordon WA group TC. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:75–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT National Institute on A, Alzheimer’s A. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkendall DT, Jordan SE, Garrett WE. Heading and head injuries in soccer. Sports Med. 2001;31:369–386. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bieniek KF, Ross OA, Cormier KA, Walton RL, Soto-Ortolaza A, Johnston AE, DeSaro P, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Wszolek ZK, Rademakers R, Boeve BF, McKee AC, Dickson DW. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:877–889. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1502-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredericks CA, Koestler M, Seeley W, Miller B, Boxer A, Grinberg LT. Primary chronic traumatic encephalopathy in an older patient with late-onset AD phenotype. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5:475–479. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carthery-Goulart MT, Anghinah R, Areza-Fegyveres R, Bahia VS, Brucki SM, Damin A, Formigoni AP, Frota N, Guariglia C, Jacinto AF, Kato EM, Lima EP, Mansur L, Moreira D, Nobrega A, Porto CS, Senaha ML, Silva MN, Smid J, Souza-Talarico JN, Radanovic M, Nitrini R. Performance of a Brazilian population on the test of functional health literacy in adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43:631–638. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102009005000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, Seichepine DR, Montenigro PH, Riley DO, Fritts NG, Stamm JM, Robbins CA, McHale L, Simkin I, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Goldstein LE, Budson AE, Kowall NW, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology. 2013;81:1122–1129. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandy S, Ikonomovic MD, Mitsis E, Elder G, Ahlers ST, Barth J, Stone JR, DeKosky ST. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: clinical-biomarker correlations and current concepts in pathogenesis. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, Lee HS, Wojtowicz SM, Hall G, Baugh CM, Riley DO, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Jacobs MA, Martin BR, Abraham CR, Ikezu T, Reichard RR, Wolozin BL, Budson AE, Goldstein LE, Kowall NW, Cantu RC. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain. 2013;136:43–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein TD, Montenigro PH, Alvarez VE, Xia W, Crary JF, Tripodis Y, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Solomon T, Meng G, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Meng S, Babcock K, Kiernan P, Murphy L, Nowinski CJ, Martin B, Dixon D, Stern RA, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, McKee AC. Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1435-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee AC, Gavett BE, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, Perl DP, Hedley-Whyte ET, Price B, Sullivan C, Morin P, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, Daneshvar DH, Wulff M, Budson AE. TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:918–929. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, Baker M, Fardo DW, Kryscio RJ, Scheff SW, Jicha GA, Jellinger KA, Van Eldik LJ, Schmitt FA. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, Personett D, Davies P, Duara R, Graff-Radford NR, Hutton ML, Dickson DW. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]