Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess general practitioner (GP) management practices related to skin cancer prevention and screening during standard medical encounters.

Setting

Data on medical encounters addressing skin cancer issues were obtained from a French database containing information from 17 019 standard primary care consultations.

Participants

Data were collected between December 2011 and April 2012 by 54 trainees who reported the regular practice of 128 GPs using the International Classification of Primary Care.

Outcome measures

Reasons for encounters and the following care processes were recorded: counselling, clinical examinations and referral to a specialist. Medical encounters addressing skin cancer issues were compared with medical encounters that addressed other health problems using a multivariate analysis.

Results

Only 0.7% of medical encounters addressed skin cancer issues. When patients did require management of a skin cancer-related issue, this was more likely initiated by the doctor than the patient (70.7% vs 29.3%; p<0.001). Compared with medical encounters addressing other health problems, encounters that addressed skin cancer problems required more tasks (3.7 vs 2.5; p<0.001) and lasted 1 min and 20 s longer (p=0.003). GPs were less involved in clinical examinations (67.5% vs 97.1%; p<0.001), both complete (7.3% vs 22.3%, p<0.001) and partial examinations (60.2% vs 74.9%), and were less involved in counselling (5.7% vs 16.9%; p<0.001). Patients presenting skin cancer issues were referred to a specialist more often than patients consulting for other health problems (39.0% vs 12.1%; p<0.001). GPs performed a biopsy in 6.7% of all skin cancer-related encounters.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates discrepancies between the high prevalence of skin cancer and the low rate of medical encounters addressing these issues in general practice. Our findings should be followed by qualitative interviews to better understand the observed practices in this field.

Keywords: Skin cancer, Primary healthcare, Prevention, Screening, Early detection of cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was conducted in a primary care setting.

The medical encounters were detailed using a validated international classification system and were not based on self-reported data.

The design ensured that general practitioners did not change their practices during the study.

The study was based on the International Classification of Primary Care, and the codes did not enable the reporting of certain clinical information.

Only 0.7% of medical encounters addressed skin cancer issues, corresponding to 123 consultations.

Introduction

Skin cancers are the most common types of cancers, and their incidence continues to rise;1–4 20% of the population may develop skin cancer during their lifetime.5 The annual incidence of non-melanoma skin cancers is estimated to range between 109 and 148/100 000 in Western countries,3 reaching 1019 and 1488/100 000 in the 60–70 years old population.6 First, the primary prevention of skin cancer based on sun avoidance is a key issue: the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends counselling children and young adults who have fair skin about minimising their exposure to ultraviolet radiation to reduce their risk of skin cancer.7 Second, skin cancer management and prognosis largely depend on the early timing of diagnosis.3 8 9 Non-melanoma skin cancers rarely result in death or substantial morbidity, but scar sequelae depend on the earliness of diagnosis. Melanoma is rarer (10% of skin cancers) but has notably higher mortality rates.8–10 The 5-year survival of melanoma ranges from 95% (Breslow thickness <1 mm) to 60% (Breslow thickness >4 mm).9 10

A number of authors have discussed the prevention and screening of these cancers in primary care.7 11–14 The role played by non-dermatologist care providers appears fundamental,11–17 and French guidelines from the National Institute for Cancer emphasise the role of primary care providers in skin cancer prevention screening.18 One reason for the importance of primary care providers is that most patients will not initiate dermatologist consultations on their own.17 19 20 Another reason is the low demographic density of dermatologists, which limits patient access to dermatologist consultations for skin examinations.

However, several authors have described that general practitioners (GPs) are uncomfortable with dermatological reasons for consultations,21 especially in cases involving suspicious lesions of skin cancer.14 22 Studies that focused on the care pathway of patients concerned by skin cancer screening suggest that GPs face difficulties in this field and essentially refer patients to dermatologists.22–24 When searching for data on GP involvement in skin disorder management in the literature, it is frustrating to realise the limited number of publications on this topic, which limits the development of guidelines.1 In the rare published studies, the reported data are sometimes biased due to self-reporting (as many authors have simply questioned GPs about their dermatology practices12 14), thus neglecting the gap between actual practices and those reported by healthcare professionals.25 Other authors aiming to describe the dermatological activity of GPs have used a database that included the three main reasons for consultations provided by the patients.26 One limitation of this approach may be that dermatological reasons are not always part of the major reasons for consultation. Some authors even suggest that in a number of cancer prevention situations, dermatological issues would not at all be part of the reasons for medical encounters reported by the patients and that these issues would rather be raised by the physician.14 Finally, providing data on skin cancer prevention and screening in primary care is difficult because skin oncology is only one issue among many others in current practice.

The aim of this study was to assess GP involvement in skin cancer prevention and screening during regular medical encounters using an observational method and an international classification to report all primary care procedures performed during the encounter.

Methods

Patient population

The study population was recruited from 28 November 2011 to 30 April 2012 among patients who were seen by 128 GPs regardless of their reasons for seeking consultation. Patients were consulted either at surgery or during home visits. Patient recruitment was distributed throughout France, depending on the locations of GP practices. Patients received oral and written information about the study at the beginning of the encounter and had to provide their written informed consent to participate. The non-inclusion criterion was patient's refusal. Assuming an average of three volunteer GPs per medical school and a total number of 100 participating GPs and 10 consultations per half-day over the study period of 22 weeks, a total of 22 000 patients was anticipated.

Method used for data collection

Study design

The study design was a cross-sectional multicentred observation of GP consultations. Data were collected using the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) codes.27–30 The ICPC is an epidemiological tool produced by the World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associates of General Practitioners/Family Physicians.27 The purpose of the ICPC is to classify data about three elements of a healthcare encounter: (1) the reasons for the encounter, (2) the diagnosis (or managed health problem), and (3) the intervention or ‘process of care’.28 In our study, the data were collected by 54 GP interns who were previously trained in the use of the ICPC for 1.5 days. Over 20 weeks, they prospectively reported on 2 half-days per week the content of all of the medical encounters they attended using the ICPC. They had a paper checklist to orient the observation. For each medical encounter, the following characteristics were also collected to characterise the patient: gender, age, patient known or new to the practice, socioeconomic category, and deprivation as determined by fee exoneration. The data were subsequently compiled daily in a secure online database.

Use of the ICPC and codes related to skin cancer issues

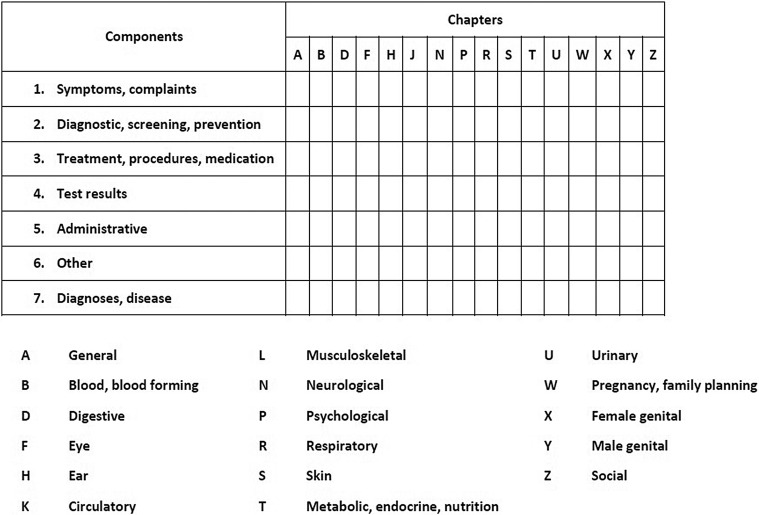

The ICPC has a biaxial structure (figure 1). One axis refers to 17 α-coded chapters, mainly based on body systems, with an additional chapter for broad, ill-defined conditions (eg, feeling tired, general ill feeling), another for psychological problems, and one for social problems. The other axis includes seven ‘identical components’. Component 1 covers symptoms and complaints. Component 7 covers diagnosis/disease, and components 2–6 are process codes (eg, check, immunisation, test results) that apply equally in all chapters. The ICPC was designed for paper-based data collection, with the primary care provider selecting the code at the time of the encounter. Rubrics bear a letter and two-digit numeric code (eg, R05 for cough; see online supplementary material file).28 31

Figure 1.

The biaxial structure of the International Classification of Primary Care.

bmjopen-2016-013033supp.pdf (76.1KB, pdf)

The ‘reasons for encounter’ are based on the patient's own words and consist of the agreed statement of the reason(s) why a patient enters the healthcare system, representing that patient's demand for care. These reasons may be symptoms or complaints (headache or fear of cancer), known diseases (influenza or diabetes), requests for preventive or diagnostic services (a blood pressure check or an ECG), a request for treatment (repeat prescription), to obtain test results, or administrative (a medical certificate). Any reason given should be coded, and multiple coding is required if the patient provides more than one reason.

‘Health problems/diagnoses’ give the ‘name’ to the episode as assessed by the provider. They can be recorded as medical diagnoses, as symptoms/complaints such as ‘fear of cancer’, as disabilities, or as need for care (eg, preventive measure: immunisation, pap smear, advice).

Interventions in the process of care refer to the following categories: (1) diagnostic, screening and preventive procedures; (2) medication, treatment; (3) administrative; and (4) referrals to healthcare professionals (see online supplementary material file).31

Medical encounters that address skin cancer issues

Based on the ICPC, two researchers (CR and SH) jointly selected the codes enabling the identification of the following: (1) encounters addressing skin cancer issues (codes S-26: ‘fear of cancer of skin’; S-77: ‘malignant neoplasm of skin’; S-79: ‘neoplasm skin benign, unspecified’; S-80: ‘solar keratosis/sunburn’); codes that were associated with a skin cancer prevention or screening procedure were included in this category, and code S-82, relating to ‘nevus/mole’, was also classified in this category, as most nevus/mole examinations are performed to eliminate melanoma; (2) encounters addressing other dermatological problems (other S codes are provided in an online supplementary material file31); and (3) encounters without any dermatological orientation (remaining codes31). The encounters were thus divided into three groups: skin cancer-related encounters, regular dermatology-related encounters and non-dermatology-related encounters.

Whether the physician or the patient initiated the process of care was investigated. The physician's involvement in the care processes related to skin cancer was subsequently characterised by distinguishing the following: counselling (code: S45), partial examination focusing on a specific skin lesion (code: S31), complete body skin examination (code: S30), referral to a dermatologist (code: S67), and biopsy or excision (code: S52; see online supplementary material file).31

Statistical analysis

The care processes implemented during encounters that addressed skin cancer issues were compared with those implemented during encounters that addressed regular dermatology issues and encounters without dermatology issues. The statistical analyses were performed using R V.3.1.0. software package. Student's test and Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test were used to analyse quantitative variables. The χ2 or Fisher's test was used for bivariate variables. A multivariate analysis led to the identification of factors associated with GP involvement in skin cancer prevention and/or screening.

Ethical approval

A statement was made to the Advisory Committee on Information Processing in Health Research (CCTIRS No.11605) and the French Commission on Information Technology and Liberties (No.1549782).

Results

Description of the patients

A total of 17 019 patients were included in the study (table 1). Men comprised 39.9%. The mean age of the population was 54.3 years. Additionally, 29.1% of all patients suffered from a chronic disease, and 3.8% had specific reimbursement facilities due to a low socioeconomic status. The characteristics of the consulting patients are reported in table 1. In the skin cancer group, two populations were under-represented: patients aged <50 years (30.9% vs 42.1%; p=0.039) and unemployed patients (5.7% vs 11.9%; p=0.005). There were no other significant differences associated with patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients in each group: medical encounters addressing skin cancer issues, encounters addressing regular dermatology issues and encounters without any dermatology issues

| Skin cancer |

Regular dermatology |

Non-dermatology |

p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=123 |

N=1521 |

N=15375 |

|||||

| n; % | Mean, SD | n; % | Mean, SD | n; % | Mean, SD | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 66; 53.7 | 915; 60.2 | 9241; 60.1 | 0.347 | |||

| Male | 57; 46.3 | 606; 39.8 | 6134; 39.9 | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Mean, SD | 59.6; 19.1 | 54.3; 19.8 | 54.3; 19.2 | 0.010 | |||

| 18–50 | 38; 30.9 | 648; 42.6 | 6479; 42.1 | 0.039 | |||

| 50–75 | 56; 45.5 | 606; 39.8 | 6348; 41.3 | 0.340 | |||

| >75 | 29; 23.6 | 267; 17.6 | 2548; 16.6 | 0.076 | |||

| Suffering from a chronic disease | 39; 31.7 | 464; 30.5 | 4442; 28.9 | 0.345 | |||

| Low socioeconomic status | 2; 1.6 | 54; 3.6 | 592; 3.9 | 0.436 | |||

| New patient | 3; 2.4 | 43; 3.6 | 757; 4.9 | 0.027 | |||

General characteristics of the medical encounters

A total of 123 skin cancer-related encounters were identified in the database, corresponding to 0.7% of the overall number of encounters reported in the database (table 2). The characteristics of these encounters were compared with those of the 1521 (8.9%) encounters that addressed regular dermatology issues and the 15 375 (90.3%) that did not address dermatology issues. In the skin cancer group, the mean duration of the consultation was significantly longer (18.41 vs 17.80 min (regular dermatology problems) vs 17.11 min (non-dermatology problems); p=0.003), and there were more reasons for the encounter (3.74 compared with 3.49 (regular dermatology) and 2.69 (non-dermatology); p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the medical encounters in each group, depending on whether the encounter addressed skin cancer issues, regular dermatology issues or non-dermatology issues

| Skin cancer N=123 |

Regular dermatology N=1521 |

Non-dermatology N=15375 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n; % | Mean, SD | n; % | Mean, SD | n; % | Mean, SD | p Value* | |

| Encounter duration (min) | 18.4; 8.3 | 17.8; 8.3 | 17.1; 8.6 | <0.001 | |||

| Number of problems | 3.7; 2.0 | 3.5; 2.1 | 2.7; 1.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Practice location | |||||||

| Rural | 23; 18.7 | 315; 20.7 | 3063; 19.9 | ||||

| Semirural | 24; 19.5 | 359; 23.6 | 3687; 24.0 | 0.59 | |||

| Urban | 76; 61.8 | 847; 55.7 | 8625; 56.1 | ||||

| Context | |||||||

| Office | 117; 95.1 | 1391; 91.5 | 14291; 92.9 | 0.017 | |||

| Home visit | 6; 4.9 | 130; 8.5 | 1084; 7.1 | ||||

*Multivariate model adjusted for gender, age, sex, suffering from a chronic disease, socioeconomic status.

Encounters that addressed skin cancer problems

Table 3 shows that certain care processes were conducted less frequently during encounters that addressed skin cancer issues: patient counselling (5.7% vs 16.9%; p<0.001) and clinical examinations (67.5% vs 97.1%; p<0.001), whether in the form of a detailed examination (7.3% vs 22.3%; p<0.001) or a partial examination (60.2% vs 74.9%; p<0.001). Certain care processes were more frequent during encounters that addressed skin cancer issues: referrals to a specialist (39.0% vs 12.1%; p<0.001) and biopsy (6.5% vs 0.1%; p=0.001).

Table 3.

Care processes implemented by the physician during medical encounters addressing skin cancer issues, regular dermatology issues or non-dermatology issues

| Skin cancer | Regular dermatology | Non-dermatology | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=123 | N=1521 | N=15375 | ||

| n; % | n; % | n; % | ||

| Counselling | 7; 5.7 | 80; 5.3 | 2601; 16.9 | <0.001 |

| Clinical examination | 83; 67.5 | 1018; 66.3 | 14933; 97.1 | <0.001 |

| Complete examination | 9; 7.3 | 112; 7.4 | 3421; 22.3 | <0.001 |

| Partial examination | 74; 60.2 | 906; 59.6 | 11512; 74.9 | <0.001 |

| Referral to a specialist | 48; 39.0 | 148; 9.7 | 1857; 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Biopsy | 8; 6.5 | 36; 2.4 | 22; 0.1 | <0.001 |

Of the 123 encounters that addressed skin cancer problems, the patient provided a reason for the encounter related to skin cancer in 29.3% (table 4). In contrast, the GP was the initiator of skin cancer prevention and/or screening in 70.7% of the cases. Table 5 shows that the doctor was more often the initiator of skin cancer prevention and/or screening for patients aged 50–75 years (OR=6.26 (1.48 to 36.72); p=0.02) and patients aged over 75 years (OR=11.71 (1.82 to 97.69); p=0.01).

Table 4.

Initiator of skin cancer prevention and/or screening process, depending on patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | Initiator of skin cancer prevention/screening |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician |

Patient |

p Value | |||

| N=87 |

N=36 |

||||

| n, % | Mean, SD | n, % | Mean, SD | <0.001 | |

| Age (years) | 61.8; 19.5 | 54.3; 17.3 | 0.038 | ||

| 18–50 | 21; 55.3 | 17; 44.7 | 0.63 | ||

| 50–75 | 42; 75.0 | 14; 25.0 | <0.001 | ||

| >75 | 24; 82.8 | 5; 17.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 42; 73.7 | 15; 26.3 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 45; 68.2 | 21; 31.8 | 0.010 | ||

| Low socioeconomic status | 1; 50.0 | 1; 50.0 | 1 | ||

| Suffering from a chronic disease | 31; 79.5 | 8; 20.5 | <0.001 | ||

Table 5.

Factors associated with seeking a GP for skin cancer issues (multivariate analysis)

| OR | (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | REF | – | – |

| Male | 1.22 | [0.49 to 3.10] | 0.67 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–50 | REF | – | – |

| 50–75 | 6.26 | [1.48 to 36.72] | 0.021 |

| 75–111 | 11.71 | [1.82 to 97.69] | 0.014 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 1.31 | [0.45 to 3.96] | 0.62 |

| Suffering from a chronic disease | 1.01 | [0.03 to 38.50] | 0.99 |

GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the low rate of medical encounters that address skin cancer problems in general practice. During skin cancer-related encounters, GPs were mainly investigating lesions, not usually performing full skin examinations nor providing education. When compared with encounters that addressed other health problems, GPs referred patients to a specialist more frequently (39.0% vs 12.1%; p<0.001) and were less involved in clinical examinations (67.5% vs 97.1%; p<0.001) and counselling (5.7% vs 16.9%; p<0.001). However, when patients required management of a skin cancer-related problem, this was more likely initiated by the doctor. The process of care was conducted 2.2 times more frequently at the physician's initiative than at the patient's initiative (70.7% vs 29.3%; p<0.001), and GP involvement increased for patients aged over 50 years (OR=6.26 (1.48 to 36.72)). Addressing a skin cancer problem was generally implemented as a supplementary task during medical encounters (3.7 vs 2.5; p<0.001), and the medical encounters were, on average, 1 min and 20 s longer (p=0.003).

The strengths of this study were the primary care setting and the observation of a large number of medical encounters, which allowed for the analysis of care processes that appeared to be rarer than 1%. The content of the encounters was reported using a validated international classification system28–30 and was not based on self-reported data. The design ensured that the GPs did not modify their practices during consultations that addressed skin cancer problems.

This study also had some limitations. The first might be the limitation to only teaching GPs. However, previous publications demonstrated that their practices were representative of French GP practices.32 33 The study used the ICPC-2, and the codes for the reason for encounter, the processes of care and health problems did not enable the reporting of certain clinical information that could have been pertinent, including information on skin cancer type and other skin cancer risk factors (sun exposure habits, previous use of tanning beds, phototype). Moreover, the skin is the largest body organ, and thus affirming that GPs did (or did not) perform a partial skin examination during a pulmonary or heart auscultation might be subject to an interpretation bias. Last but not least, patients were recruited over the winter months (November to April). Generalisation of our results to the whole year should be cautious as patients and GPs concern for skin cancer might be higher during the summer period.

The results of the study demonstrated that the situations in which patients spontaneously consulted a GP to report a suspect skin lesion were in the minority. Prevention and screening practices were two times more often the result of active GP involvement. In a previous publication, Walter et al34 reported similar results, particularly for patients aged over 60 years. The increasing involvement of physicians with respect to more elderly patients (after age 50 years and then after age 75 years) is consistent with the reported incidence of the disease, as 75% of skin cancers emerge after the age of 50 years.6 In a previous study, we demonstrated that men, older patients, patients suffering from chronic diseases, and low-income patients were less likely to benefit from screening.35 These new study findings suggest that physicians might be more strongly involved in these populations. However, skin cancer issues would not at all be part of the reasons for medical encounters reported by these patients. Buster et al36 reported that the elderly consider themselves at lower risk of developing skin cancer. Reen et al37 have reported that most elderly do not consult physicians despite the existence of screening campaigns.

This study thus provides insight into the role played by GPs in skin cancer counselling, clinical examinations and referrals. First, the limited involvement of physicians in counselling is a surprising but nonetheless relevant finding. The pathogenesis of skin cancers requires counselling and sun exposure prevention.7 Several studies have reported that physician counselling was more effective than that provided in the context of more impersonal communication modalities.38 39 In preventive settings, Hollands et al40 demonstrated the benefit of counselling based on showing the patient the lesion on his/her body. Patient education might be a potential pathway for improvement in skin cancer prevention.

The low rate of clinical examinations is another relevant finding. This low rate seems paradoxical because skin cancer screening is based on physical examinations. The low examination rate could be related to time constraints. Indeed, this study revealed that skin cancer prevention was often a supplementary care process performed at the physician's initiative. However, the corresponding medical encounters were only ∼80 s longer. This additional time interval seems insufficient to enable a complete body skin examination. One potential explanation could be that the time constraint prevented the performance of a complete body skin examination if one had not been scheduled.

Finally, in this study, the GPs referred patients to a specialist in 39% of the cases (threefold more than for other medical encounters). This finding is consistent with the results of a previous French study.23 In this first publication, which focused on a pilot melanoma screening programme, it was unclear whether the high rate of referral observed was a result of the new innovative procedure tested in GP practices or whether it represented the regular referral proportion of French GP practices. Based on this new observational study, this finding suggests a failure in the role of GPs as gate keepers, despite the fact that this role is widely implemented in European countries.41 Our findings demonstrate the unique nature of dermatological issues, as referral to specialists for these issues appeared to be more important than referrals to other specialists (table 3). One potential explanation could be that the GPs did not feel qualified to conduct a skin examination of suspect lesions. GPs may therefore tend to refer the patient to a dermatologist if there is the slightest doubt that the lesion could be malignant, sometimes without even examining the patient. This might be linked to specifics regarding French clinical practice, as patients could have direct access to dermatologists until 2007. However, further studies are needed to further examine this paradoxical result.

In conclusion, this study highlights that skin cancer prevention and screening are infrequent in general practice. GPs examine only a minority of patients. One potential explanation could be that the GPs did not feel qualified to conduct skin examinations of suspect lesions, and thus referrals to the specialist were three times more frequent for consultations focusing on skin cancer than for other consultations. Further research conducting qualitative interviews of GPs regarding our findings might provide a better understanding of the observed practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the 54 trainees for their participation in data collection, the 128 GPs who agreed to take part in the study, and the French medical schools involved in the ECOGEN study (Amiens, Angers, Besançon, Bordeaux, Brest, Clermont Ferrand, Dijon, Grenoble, Lille, Limoges, Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier, Nancy, Nantes, Nice, Paris Descartes, Paris Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris Diderot, Paris Est Créteil, Paris Ile-de-France Ouest, Poitiers, Rennes, Rouen, St-Etienne, Strasbourg, and Tours).

Footnotes

Contributors: CR conceived the study, was responsible for its supervision and was responsible for drafting the manuscript. SH participated in the database extraction and participated in drafting the manuscript. AG performed the statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript. CG helped participate in study supervision and helped draft the manuscript. AM was responsible for the GP network and for the data collection. LL was responsible for the design of the ECOGEN study and helped draft the manuscript. BD participated in the supervision and provided administrative and technical support. JMN participated in the design of the study, was responsible for the statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript.

Funding: Pfizer and the French National College of Generalist Teachers (Collège National des Généralistes Enseignants Conseil) provided financial support for the ECOGEN project.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board Sud-East IV (No L11-149).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ et al. , US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for skin cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;316:429–35. 10.1001/jama.2016.8465 10.1001/jama.2016.8465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao H, Weinstock MA. Visual inspection and the US preventive services task force recommendation on skin cancer screening. JAMA 2016;316:398–400. 10.1001/jama.2016.9850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madan V, Lear JT, Szeimies RM. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Lancet 2010;375:673–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61196-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder-Foucard F, Belot A, Delafosse P et al. . Estimation nationale de l'incidence et de la mortalité par cancer en France entre 1980 et 2012. Partie 1–Tumeurs solides. Saint-Maurice (Fra): Institut de veille sanitaire, 2013:122 p. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleavenger J, Johnson SM. Non melanoma skin cancer review. J Ark Med Soc 2014;110:230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diffey BL, Langtry JA. Skin cancer incidence and the ageing population. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:679–80. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician 2012;86:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. How many people survive 5 years or more after being diagnosed with melanoma of the skin? http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html#survival.

- 9.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Atkins MB et al. . An evidence-based staging system for cutaneous melanoma. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:131–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Leest RJ, Van Steenbergen LN, Hollestein LM et al. . Conditional survival of malignant melanoma in The Netherlands: 1994–2008. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:602–10. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. A review of the literature. Arch Fam Med 1999;8:170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpern AC, Hanson LJ. Awareness of, knowledge of and attitudes to non-melanoma skin cancer and actinic keratosis among physicians. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:638–42. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg A, Geller A. Need to improve skin cancer screening of high-risk patients: comment on “Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists”. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:44–5. 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF et al. . Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:39–44. 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resneck JS, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? Trends in the use of non-physician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:211–16. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowell BA, Froelich CW, Federman DG et al. . Dermatology in primary care: prevalence and patient disposition. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:250–5. 10.1067/mjd.2001.114598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander Horst A et al. . Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:956–7. 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French National Institute for Cancer. [Screening and Early detection of Cancer. Clinical Practice Guidelines]. http://www.e-cancer.fr/Professionnels-de-sante/Depistage-et-detection-precoce/Detection-precoce-des-cancers-de-la-peau/Aide-pour-votre-pratique

- 19.White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med 1961;265:885–92. 10.1056/NEJM196111022651805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green LA, Fryer GE Jr, Yawn BP et al. . The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med 2001;344:2021–5. 10.1056/NEJM200106283442611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kownacki S. Skin diseases in primary care: what should GPs be doing? Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:380–1. 10.3399/bjgp14X680773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argenziano G, Puig S, Zalaudek I et al. . Dermoscopy improves accuracy of primary care physicians to triage lesions suggestive of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1877–82. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rat C, Quereux G, Grimault C et al. . Melanoma incidence and patient compliance in a targeted melanoma screening intervention. One-year follow-up in a large French cohort of high-risk patients. Eur J Gen Pract 2015;21:124–30. 10.3109/13814788.2014.949669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rat C, Grimault C, Quereux G et al. . Proposal for an annual skin examination by the general practitioner for patients at high risk for melanoma. A French cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007471 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res 1993;20:303–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleischer AB, Herbert CR, Feldman SR et al. . Diagnosis of skin disease by nondermatologists. Am J Manag Care 2000;6:1149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. http://www.globalfamilydoctor.com/groups/WorkingParties/wicc.aspx.

- 28. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/adaptations/icpc2/en/

- 29.Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes IM. International primary care classifications: the effect of fifteen years of evolution. Fam Pract 1992;9:330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soler JK, Okkes I, Wood M et al. . The coming of age of ICPC: celebrating the 21st birthday of the International Classification of Primary Care. Fam Pract 2008;25:312–17. 10.1093/fampra/cmn028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. http://www.kith.no/upload/2705/icpc-2-english.pdf.

- 32.Gelly J, Le Bel J, Aubin-Auger I et al. . Profile of French general practitioners providing opportunistic primary preventive care: an observational cross-sectional multicentre study. Fam Pract 2014;31:445–52. 10.1093/fampra/cmu032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letrilliart L, Rigault-Fossier P, Fossier B et al. . Comparison of French training and non-training general practices: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:126 10.1186/s12909-016-0649-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter FM, Humphrys E, Tso S et al. . Patient understanding of moles and skin cancer, and factors influencing presentation in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:62 10.1186/1471-2296-11-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rat C, Quereux G, Grimault C et al. . Inclusion of populations at risk of advanced melanoma in an opportunistic targeted screening project involving general practitioners. Scand J Prim Health Care 2016;34:286–94. 10.1080/02813432.2016.1207149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M et al. . Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66:771–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reen B, Coppa K, Smith DP. Skin cancer in general practice: impact of an early detection campaign. Aust Fam Physician 2007;36:574–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falk M, Magnusson H. Sun protection advice mediated by the general practitioner: an effective way to achieve long-term change of behaviour and attitudes related to sun exposure? Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:135–43. 10.3109/02813432.2011.580088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rat C, Quereux G, Riviere C et al. . Targeted melanoma prevention intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:21–8. 10.1370/afm.1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollands GJ, Hankins M, Marteau TM. Visual feedback of individuals’ medical imaging results for changing health behaviour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(20):CD007434 10.1002/14651858.CD007434.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masseria C, Irwin R, Thomson S et al. . Primary care in Europe. European Commission report 2009.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013033supp.pdf (76.1KB, pdf)