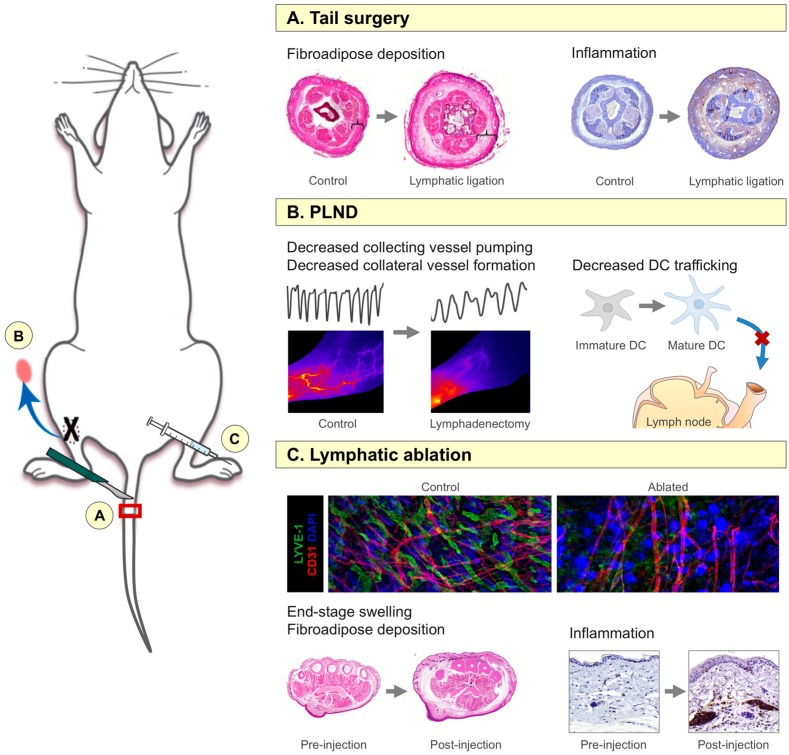

Figure 1.

Mouse models of lymphedema. (A) Tail surgery model, in which the lymphatics are ligated after circumferential full-thickness skin excision and identification with blue dye. Note the increase in fibroadipose thickness and inflammation following lymphatic injury; inflammatory cells are indicated by the brown color; (B) Popliteal lymph node dissection (PLND) model, similar to the axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) model, in which the appropriate lymph node is removed with its corresponding fat pad (as indicated by the blue arrow). This model is particularly useful for evaluation of collecting vessel pumping, collateral lymphatic formation, and dendritic cell (DC) trafficking, all of which are decreased following lymphadenectomy. In the left panel, note the decreased frequency of collecting vessel pumping as indicated by the black line graphs (each peak represents one pump; arbitrary units) and the paucity of patent collecting lymphatic vessels as indicated by absence of distinct vessels highlighted by the red/orange dye in mice that had undergone lymphadenectomy compared to control mice. Lymphatic injury also prevents transport of mature DCs to lymph nodes, where they would initiate immune responses; (C) Diphtheria toxin-mediated lymphatic ablation model, in which human diphtheria toxin receptor is coupled with lymphatic-specific receptor promoter Fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4) using Cre-Lox technology. After activation with tamoxifen, diphtheria toxin (DT) can be injected into any limb for local ablation. Note the paucity of LYVE-1+ lymphatic vessels (green) with preservation of CD31+ blood vessels (red); DAPI staining of nuclei is represented in blue. This model also results in prolonged hindlimb swelling and increased inflammation up to one year post-injection; inflammatory cells are indicated by the brown color.