Rare diseases are defined by a limited prevalence of ≤5 cases per 10 000 individuals in Europe [1]. This definition includes around 8000 diseases, many of which are unknown not only to the public but also to the vast majority of healthcare professionals and text books. It is estimated that, as a whole, rare diseases affect around 25 to 30 million people in Europe. Most rare diseases are chronic and debilitating and appear in early childhood or young adulthood, accounting for a significant proportion of infant mortality and childhood/life-long disability. Rare diseases have a number of problems in common: 1) being “invisible” to the healthcare systems; 2) the paucity of experts; 3) the lack of appropriate treatments; and 4) the social exclusion faced by patients and their families [1]. Specific coordinated initiatives in the field of rare diseases are required so as to assure equity in the provision of care, development of best practice, and adequate information for the healthcare professionals and society at large.

Short abstract

General Practitioners need support to recognise rare lung disorders and advise patients on the best available care http://ow.ly/kDgy304rX94

Introduction

Rare diseases are defined by a limited prevalence of ≤5 cases per 10 000 individuals in Europe [1]. This definition includes around 8000 diseases, many of which are unknown not only to the public but also to the vast majority of healthcare professionals and text books. It is estimated that, as a whole, rare diseases affect around 25 to 30 million people in Europe. Most rare diseases are chronic and debilitating and appear in early childhood or young adulthood, accounting for a significant proportion of infant mortality and childhood/life-long disability. Rare diseases have a number of problems in common: 1) being “invisible” to the healthcare systems; 2) the paucity of experts; 3) the lack of appropriate treatments; and 4) the social exclusion faced by patients and their families [1]. Specific coordinated initiatives in the field of rare diseases are required so as to assure equity in the provision of care, development of best practice, and adequate information for the healthcare professionals and society at large.

In this context, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and European Lung Foundation (ELF) share the responsibility of fostering educational activities throughout Europe to increase the awareness of rare lung diseases. In our view, educational efforts should focus on general practitioners (GPs) and primary care as a crucial target, since these represent the front line for patients. Educational activities should, therefore, be appropriate for GPs and the primary care setting where respiratory disorders, in particular respiratory rare diseases, are just a small part (in the case of rare diseases usually a tiny part) of everyday practice. The European Union (EU) has also decided to confront the issue of rare diseases to try and identify strategies to improve their diagnosis and care. Among the most important EU initiatives to date, a European Commission communication on rare diseases has been approved and a Council Recommendation submitted to the European parliament [1, 2].

In this context, the aims of this educational Task Force were to: 1) investigate the degree of awareness about rare lung diseases among GPs across Europe; and 2) develop educational material designed to raise awareness about rare lung diseases and guide GPs and primary care workers in dealing with them.

Methods

Composition of the Task Force

The Task Force was designed to be a joint collaboration of the different stakeholders involved in rare lung diseases. Members included rare lung disease experts within the ERS, rare disease experts from the EU Rare Disease Task Force, representatives of rare lung disease patients’ associations, and GPs participating in the ERS Clinical Assembly.

Identification of the diseases to address in the project

The aim of this project, the first of its kind, was to create a guideline “template” for all rare diseases involving the lungs. As the diseases falling into this category are too many to enumerate, it would have been impossible to create statements on all of them in the first instance. Hence, a limited number were selected by the members of the Task Force, based on their knowledge and experience through a consensus method. The selection was based on multiple criteria (including the prevalence of the disease, level of difficulty of making a diagnosis, consequences of a delay in diagnosis and complexity of the management) with the aim of giving precedence to those rare lung diseases that are most relevant for general practice and patients. At the end of the process three adult rare lung diseases were selected (α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)) and three paediatric rare lung diseases were selected (cystic fibrosis (CF), primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) and primary immunodeficiencies).

Aim 1: investigate degree of awareness about rare lung diseases among GPs in Europe

In order to test the level of awareness about the selected rare lung diseases we designed two questionnaires (one for adult rare lung disease and the other for paediatric rare lung diseases) aimed at reaching a large number of adult and paediatric GPs across Europe. In developing the questionnaire items, we proceeded with a Delphi consensus method among members of the Task Force and set up a series of questions on the specific rare lung diseases selected and in general on the role of primary care in identifying rare lung diseases. By the same method we identified a set of “closed” answers pertaining to each question on adult and paediatric rare lung diseases; GPs were asked to rate how correct, i.e. appropriate, each answer was. For each question we also included one “fake” answer, i.e. an answer that any physician even vaguely familiar with the rare lung disease would immediately recognise as wrong. The adult rare lung diseases questionnaire contained three questions each on AATD, PAH and LAM, the paediatric rare lung diseases questionnaire contained four questions on CF, three questions on PCD and two on primary immunodeficiencies. Each question had seven options of answer, of which one only was completely wrong, while the others were “right” in varying degrees. The respondent had to rate each answer on a five-point Likert scale: 0=not at all appropriate/false; 1=slightly appropriate; 2=moderately appropriate; 3=very appropriate; 4=extremely appropriate. If the GP was unsure about the answer it was possible to select the box “I don’t know”.

The questionnaires were then completed with an introductory part containing general questions, e.g. the number of patients in the GP’s practice, whether the GP had patients with rare lung diseases, etc. The two questionnaires are available as supplementary data. The survey invitation and questionnaire were available on the ERS and International Primary Care Respiratory Group website (courtesy of N. Chavannes). Data were collected via the internet and also, in order to reach a sufficient number of participants, via face-to-face interviews with GPs in Italy (Pavia and Novara provinces). We were only able to organise interviews in this country.

Data analysis

The responses to the general part of the two questionnaires were summarised for the entire sample in descriptive terms and expressed as number and relative percentage, including a percentage of valid cases. Concerning the second part of the questionnaires with disease-specific questions, the results were reported separately for the adult and paediatric rare lung disease questionnaires and were expressed in terms of the number and percentage of wrong responses. For the calculation of wrong responses, only the one “fake” option among the answers to each question was considered, and the GP’s response was considered wrong if the grade attributed to it was > 0. The corresponding percentage was calculated as the number of wrong responses divided by the number of valid cases (i.e. total responses minus missing responses minus “I don’t know” answers). All the other “right” options to which GPs attributed a 0 grading by way of response were analysed as wrong responses in a separate analysis.

Aim 2: develop educational material to raise awareness about rare lung diseases and guide GPs and primary care workers in dealing with them

Identification of information to include in the statements and writing of them

In preparing the educational statements we aimed to include the most useful practical information related to each selected rare lung disease (e.g. diagnostic criteria, management, possible areas for patient self-management, psychological/social problems, etc.). The statements were written up in a practical style. For each of the six selected diseases a document was prepared. Particular attention was given to: 1) clinical presentation and differential diagnosis (these are the first items addressed); 2) specific clinical problems arising in the course of the disease; 3) current treatments and related problems/side-effects; and 4) psychological management of rare lung disease patients and their families. Part of the task of doctors nowadays is filtering the information available on the internet, which more and more often is also consulted by patients (again, with geographic differences within Europe); this is particularly true for rare diseases where the information is scarce. Therefore, in the statements, indications were provided of reliable sources (internet and non-internet) to consult for information on rare diseases in general, clinical trials and new research. Information was also provided about the availability of orphan drugs/treatments for each rare lung disease, possible side-effects and management of the treatment. Advice on genetic diagnosis and counselling was offered where appropriate. The final documents produced contain precise information, but in a highly synthetic form.

Results

Sample description

The questionnaires were accessed by 307 GPs, 111 of whom did not fill them out (17 questionnaires only had the general part completed and were not considered as valid). The final sample of questionnaires for analysis was 196. The adult questionnaire was completed by 170 GPs (20 of whom also completed the paediatric questionnaire). The majority of respondents were Italian (n=127), while 43 were of other nationalities (table 1).

Table 1.

Adult questionnaire: GP distribution by country

| Country | Respondents n |

| Italy | 127 |

| Portugal | 10 |

| Slovenia | 7 |

| UK | 4 |

| Spain | 2 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Poland | 1 |

| Finland | 1 |

| Pakistan | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| India | 2 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| Cyprus | 1 |

| Unknown | 6 |

The paediatric questionnaire was completed by 46 paediatric GPs, 28 from Italy and 18 from other countries (table 2).

Table 2.

Paediatric questionnaire: GP distribution by country

| Country | Respondents n |

| Italy | 28 |

| Portugal | 8 |

| UK | 3 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Slovenia | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| Pakistan | 1 |

Results of the questionnaires

General

Data for the general part of the questionnaires showed that 74% of the GPs surveyed had >1000 patients under their care (table 3). For GPs with both adult and paediatric patients, in the majority of cases paediatric patients represented only 5–10% of their patients overall (table 4).

Table 3.

Number of patients (adult and paediatric) per GP

| Patients in GP’s care | GPs n | % of all GPs# | % of GPs who responded to the question |

| Data missing | 8 | 4.1 | |

| >1500 | 73 | 37.2 | 38.83 |

| 1500–1001 | 66 | 33.7 | 35.11 |

| 1000–501 | 38 | 19.4 | 20.21 |

| 500–250 | 11 | 5.6 | 5.85 |

| Total | 196 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Proportion of paediatric patients (aged 0–17 years) in the care of GPs with both adult and paediatric patients

| Paediatric patients % | GPs n | % of all GPs# | % of GPs who responded to the question |

| Data missing | 87 | 44.4 | |

| 0 | 13 | 6.6 | 11.93 |

| 5–10 | 47 | 24.0 | 43.12 |

| 10–15 | 12 | 6.1 | 11.01 |

| 15–20 | 11 | 5.6 | 10.09 |

| 50–100 | 26 | 13.3 | 23.85 |

| Total | 196 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

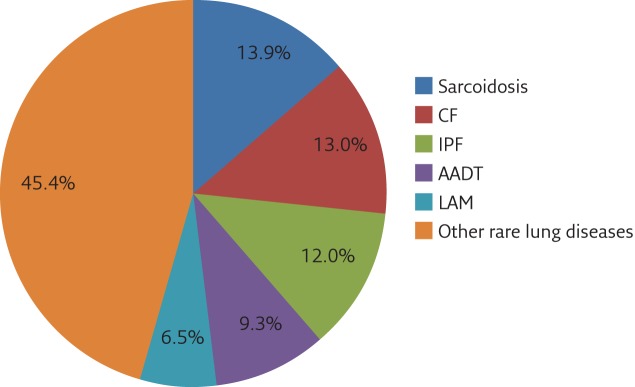

Interestingly, 41% of GPs surveyed had patients with a rare lung disease. Among the most common were sarcoidosis, CF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, AATD and LAM, together representing ∼55% of all rare lung diseases (figure 1 and table 5).

Figure 1.

Proportion of the different rare lung disease among patients of general practitioners. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Table 5.

Rare lung diseases present among patients of GPs surveyed

| Rare lung disease | Patients n |

| Sarcoidosis | 15 |

| CF | 14 |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 13 |

| AATD | 10 |

| LAM | 7 |

| Other rare lung diseases# | |

| Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | 6 |

| Bronchiectasis | 6 |

| PAH | 5 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 3 |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 2 |

| Others | 28 |

| Total | 109 |

#: n=50.

Table 6.

Results of the questionnaire relating to AATD

| Wrong responses | |

| What are the main symptoms/signs/manifestations that could be suggestive AATD? | |

| Wrong option: osteomyelitis | 53% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 10 (0–53)% |

| What type of pattern of lung/respiratory function test would be suggestive of AATD? | |

| Wrong option: restrictive pattern | 68% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 11 (2.5–68)% |

| What type of blood lab examination is suggestive of AATD? | |

| Wrong option: increased peripheral blood α1-antitrypsin | 21% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 10 (5–23)% |

Data are presented as median (min–max), unless otherwise stated. Definition of wrong option/answer: responses were considered wrong when a grade >1 was attributed. The percentage of wrong responses was calculated on valid responses (i.e. after missing and “I don’t know” responses were excluded) and is the sum of two contributions. Wrong option: responses were considered wrong when a grade >0 was attributed to the wrong option in the questionnaire. All other options: responses were considered wrong when a grade = 0 was attributed to the other options in the questionnaire. The summary figure is reported in terms of median (minimum–maximum) of the percentages of wrong responses to each option.

Only 10% of respondents were aware of the current guidelines for the treatment of patients with rare lung diseases. Furthermore, only 25% of GPs correctly answered the question: “Define a rare disease based on prevalence in the general population”. According to the Orphan Drugs Regulations EC/141/2000, the prevalence threshold is <5 cases per 10 000 individuals.

Specific questions

The analysis of the responses showed a lack of general knowledge of rare lung diseases, at least those tested by the questionnaires. Concerning AATD, the majority of GPs gave incorrect answers to the questions relating to lung abnormalities associated with AATD, while a minority incorrectly answered the question about the diagnostic criteria for AATD: i.e. only 21% believed that increased, instead of decreased, levels of blood α1-antitrypsin is the hallmark of this condition (table 6). Similar data were collected concerning GPs’ level of knowledge about PAH and LAM (table 7), with high percentages of GPs choosing the wrong answer and/or not considering the right answer to be correct by grading them 0 (i.e. wrong or not applicable).

In the paediatric rare lung diseases questionnaire, the number of paediatric GPs who completed the questionnaire was much lower than the number of GPs who completed the adult questionnaire. Nonetheless, the data were similar to those for adult GPs, with very high average percentages of wrong responses concerning the “wrong” answer option. This suggests a poor knowledge of the main symptoms/manifestations that could be suggestive of rare lung diseases in children. However, it is important to note that the percentage of errors concerning the “right” answers was on average very low (5%) (table 8).

Table 7.

Results of the paediatric questionnaire relating to PAH and LAM

| Wrong responses | |

| What are the main symptoms/manifestations that could be suggestive of PAH? | |

| Wrong option: vision abnormalities | 62% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 10 (1–62)% |

| What are the main findings that could be suggestive of PAH? | |

| Wrong option: loose shoulders | 49% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 4 (0–49)% |

| What type of pattern of lung/respiratory function abnormalities would be suggestive of PAH? | |

| Wrong option: sleep apnoea/hypopnea | 84% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 26 (1–84)% |

| What are the main symptoms/signs/manifestations that could be suggestive of LAM? | |

| Wrong option: erythema nodosum | 64% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 9 (1–64)% |

| What type of pattern of lung function test would be suggestive of LAM? | |

| Wrong option: respiratory acidosis | 81% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 11 (3–81)% |

| What type of finding at imaging studies would be suggestive of LAM? | |

| Wrong option: cerebrovascular abnormalities on brain CT | 60% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 12 (3–61)% |

Data are presented as median (min–max), unless otherwise stated. The percentage of wrong responses was calculated on valid responses (i.e. after missing and “I don’t know” responses were excluded) and is the sum of two contributions. Wrong option: responses were considered wrong when a grade >0 was attributed to the wrong option in the questionnaire. All other options: responses were considered wrong when a grade = 0 was attributed to the other options in the questionnaire. The summary figure is reported in terms of median (minimum–maximum) of the percentages of wrong responses to each option. CT: computed tomography.

Table 8.

Results of the questionnaire relating to rare lung diseases

| Wrong responses | |

| Which findings of imaging suggest CF? | |

| Wrong option: bilateral pleural effusion | 79% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 5 (0–13)% |

| Which findings of imaging suggest PCD? | |

| Wrong option: biliary stones | 78% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 0 (0–18)% |

| Which investigations should be undertaken to diagnose PCD? | |

| Wrong option: arterial blood gas analysis | 83% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 5 (0–9)% |

| What are the main symptoms/signs/manifestations that could be suggestive of lung disease in a child with immunodeficiency? | |

| Wrong option: hyperhidrosis | 88% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 0 (0–8)% |

| What are the main physical signs and findings that could be suggestive of lung disease due to immunodeficiency? | |

| Wrong option: normal physical examination | 70% |

| All other options: grading=0 | 5 (0–22)% |

Data are presented as median (min–max), unless otherwise stated. The percentage of wrong responses was calculated on valid responses (i.e. after missing and “I don’t know” responses were excluded) and is the sum of two contributions. Wrong option: responses were considered wrong when a grade >0 was attributed to the wrong option in the questionnaire. All other options: responses were considered wrong when a grade = 0 was attributed to the other options in the questionnaire. The summary figure is reported in terms of median (minimum–maximum) of the percentages of wrong responses to each option.

Diffusion of the statements

All statements have been published previously [3–8]. A wider diffusion of the questionnaire is hoped for through rare lung diseases patients associations, during ERS sponsored events, and through the organisation of an ERS postgraduate course for GPs on this topic.

Discussion and future perspectives

A large number of diseases of the lungs are rare. Most of them affect children and young adults and have a very severe prognosis. Even though the burden of morbidity and mortality of rare lung diseases is not comparable to that of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or lung cancer, they nevertheless account for a significant proportion of lung transplants and fatal outcomes for respiratory conditions in childhood and young adulthood. For example, rare lung diseases are the cause of all lung transplants not due to COPD in adults, and the primary cause of lung transplantation in children [9]. Drug companies may not see profits in rare diseases and patient numbers are often too small for large clinical trials to be performed following the rules employed for the most prevalent lung disorders, such as COPD and asthma. As a result, most rare lung disease are rarely the object of research, experts are sparse and the knowledge about these diseases among health professionals, health policy makers and the general public is poor.

ELF has published an educational factsheet on rare lung disease, and has identified this as an area requiring attention from the international scientific community [10]. In this context, the present initiative was intended as an educational aid for GPs and primary care workers in general. At the same time, collaboration with existing networks on rare diseases and patients’ associations is crucial in order to raise the educational awareness of the whole community. Better knowledge and information about rare lung disease is crucial to reduce the diagnostic delay typical of most of these diseases (up to 30 years) and to ensure that best practice is applied. In general, a better awareness about rare lung diseases would also help foster research into novel treatment modalities and epidemiological research, identifying areas of public funding and solving treatment inequalities.

The role of GPs and the existing initiatives

One important initiative of the European Commission’s communication on rare diseases is to support the creation of European reference networks for rare diseases. While networks are fundamental to develop best practice and research, and serve as a reference for diagnosis and management guidance, GPs are the ones at the frontline of the healthcare system (both for paediatric and adult patients), and all of them will encounter patients with rare lung diseases during their professional life. Most patients initially present to GPs with symptoms and then visit a GP between visits to the specialist (with differing frequency in different healthcare systems). The patients will need to receive the diagnosis and treatment of common ailments from the GP [11]. GPs that have patients with a rare disease might be called on to play a role in preventive activities and genetic counselling, as many rare diseases are genetic diseases. The care of patients affected by a rare lung disease is often difficult not only from the clinical but also from the psychological point of view, due to the severity of most illnesses and feelings of social isolation and discrimination that so often accompany such patients.

Due to the intrinsic nature and diversity of rare diseases, including those related to the lung and respiratory system with systemic manifestations, each rare disease would require, and sometimes has, its own clinical guideline/consensus statement. However, the problem, when viewed from a primary care perspective, is somewhat different as primary care workers need more an educational type of structured aid referring to the problem of rare diseases in general, in our case of rare lung diseases.

At present there are few examples of existing general guidelines on rare diseases. In Australia the need for such guidelines has recently been advocated and GP guidelines have been developed for myalgic encephalopathy and chronic fatigue syndrome [11]. In the Netherlands, the Duchenne’s patient association promoted the development of guidelines for this specific disease, written in collaboration with GPs and experts on the disease [12]. Regarding rare lung diseases, some guidelines for health professionals exist in French (GERMOP) [13]. A limited number of international websites present brief information in English about rare lung diseases [14, 15]. The number of diseases addressed by these websites is limited and the sources of information are often not shown. The most comprehensive source of information about rare lung diseases is the Orphanet website where a description of several rare lung diseases is provided [15].

Our Educational Task Force was composed of experts in rare diseases and rare lung diseases, GPs and patient representatives, with the aim of creating consensus statements for use by those who happen to be the first doctors to see a patient with symptoms of a rare lung disease, or who are called to manage this kind of patient on a routine basis, with more or less frequent collaboration with the reference centre. Written as a practical guide for use in general practice, these statements provide a reference tool for all non-pulmonary specialists confronted with symptoms of a rare lung disease, and a quick consultation tool for pulmonary physicians.

As a limitation of our study, the fact that the majority of GPs who completed the questionnaires were from one country (Italy) introduces a bias in this survey and suggests that other and more participated efforts in this field are needed in the future.

It also has to be considered that it is very difficult, if not impossible, for a GP to be knowledgeable about all rare diseases as there are several thousand of them, including but not limited to rare lung diseases [16, 17]. Usually, a rare disease only occasionally becomes familiar to GPs, when an affected family is identified in their practice population. This justifies, at least in part, the results of our survey. The same argument shows the clear necessity of an online user-friendly website, based on already existing materials and preferably with an online consultation for GPs and primary care workers in case they encounter a potential rare lung disease.

The diffusion of educational material, including the present article, for GPs and other physicians on rare lung disease is the key problem. Awareness for rare lung disease is a goal to reach overcoming many obstacles, many factors may make it difficult to reach sufficient awareness about rare lung disorders. ERS is the leading scientific society in this field and thus we have a good starting point with this ERS Task Force. However, we clearly need to go beyond the boundaries of respiratory medicine. Patient associations (through ELF) could be another pillar of this action, as well as connections with GPs societies and associations. Clearly, this is a matter of priority in health policy and the EU is the body to address with an advocacy activity.

In conclusion, the main message from this educational Task Force is that we need to raise awareness on rare lung diseases in general, in particular among GPs and primary care workers as they represent the first-line in any health system.

Acknowledgements

We thank all GPs who voluntarily replied to our questionnaires. We are indebted to N. Chavannes for his help in recruiting GPs through a website and to D. Vallese who helped in collecting and analysing the data throughout the Task Force and revised and corrected the text of the reports.

The members of the Task Force are as follows. Chairs: B Balbi and K.H. Carlsen. Coordinator: P. Baiardi. Members: S. Ayme and L. Fregonese (experts in rare diseases); L. Nicod, J-F. Cordier and C. Robalo Cordeiro Jr (adult pulmonologist); A. Boehler (lung transplant specialist); N. Chavannes and M. Levy (adult primary care physicians); A. Ostrem and B. Stallberg (paediatric primary care physicians); G. Hedlin, J. de Jongste and F. de Benedictis (paediatric pulmonologist); L. Colm and I. Annesi-Maesano (public health experts); A. Kole, V. Bottarelli and Eurodis (patient representatives).

Footnotes

This task force document was endorsed by the ERS Science Council and ERS Executive Committee on September 5 and 7, 2016.

Supplementary material This article has supplementary material from breathe.ersjournals.com

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions on Rare Diseases: Europe’s challenges. 11.11.2008. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/non_com/docs/rare_com_en.pdf Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 2.Commission of the European Communities. Proposal for a council recommendation on a European action in the field of rare diseases. 11.11.2008 http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/non_com/docs/rare_rec_en.pdf Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 3.Powell P, Maesfield S, Anderson L, et al. . Support Healthy Lungs for Life: holding a spirometry event. Breathe 2014; 10: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jongste JC. GPs meet rare lung disorders Task Force factsheet: childhood interstitial lung disease. Breathe 2014; 10: 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlsen K-H. GPs meet rare lung disorders Task Force factsheet: lung disease in children with immunodeficiencies. Breathe 2014; 10: 217–272. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedlin G. GPs meet rare lung disorders Task Force factsheet: cystic fibrosis. Breathe 2014; 10: 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Benedictis FM. GPs meet rare lung disorders Task Force factsheet: primary ciliary dyskinesia. Breathe 2014; 10: 159–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galiè N, Manes A, Palazzini M. GPs meet rare lung disorders Task Force factsheet: pulmonary arterial hypertension. Breathe 2014; 10: 233–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Görle H, Strüber M, Ballmann M, et al. . Lung and heart-lung transplantation in children and adolescents: a long-term single-center experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009; 28: 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Lung Foundation. Rare and ‘orphan’ lung diseases. www.europeanlung.org/assets/files/en/publications/rare_lung_diseases.pdf Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 11.Knight AW, Senior TP. The common problem of rare disease in general practice. Med J Aust 2006; 185: 82–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nederlands huisartsen genootsxhap. Informatie voor de huisarts over Duchenne spierdystrofie www.nhg.org/sites/default/files/content/nhg_org/uploads/duchenne.pdf Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 13.Centre de référence. Documents d’aide à la prise en charge. Références pratiques actuelles. http://maladies-pulmonaires-rares.fr/centre-reference/aide-prise-en-charge/References-pratiques-actuelles Date last updated: April 28, 2015. Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) www.nice.org.uk Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 15.Orphanet www.orpha.net Date last accessed: October 15, 2016.

- 16.Treweek S, Flottorp S, Fretheim A, et al. . [Guidelines in general practice – are they read and are they used?] Tidsskrift Nor Lægeforen 2005; 125: 300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgers JS, Grol RP, Zaat JO, et al. . Characteristics of effective clinical guidelines for general practice. Br J Gen Practice 2003; 53: 15–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]