Abstract

The concentration of CO2 in many aquatic systems is variable, often lower than the KM of the primary carboxylating enzyme Rubisco, and in order to photosynthesize efficiently, many algae operate a facultative CO2 concentrating mechanism (CCM). Here we measured the responses of a marine diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana, to high and low concentrations of CO2 at the level of transcripts, proteins and enzyme activity. Low CO2 caused many metabolic pathways to be remodeled. Carbon acquisition enzymes, primarily carbonic anhydrase, stress, degradation and signaling proteins were more abundant while proteins associated with nitrogen metabolism, energy production and chaperones were less abundant. A protein with similarities to the Ca2+/ calmodulin dependent protein kinase II_association domain, having a chloroplast targeting sequence, was only present at low CO2. This protein might be a specific response to CO2 limitation since a previous study showed that other stresses caused its reduction. The protein sequence was found in other marine diatoms and may play an important role in their response to low CO2 concentration.

Diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) are one of the major primary producers in the ocean responsible for about one fifth of the photosynthesis on Earth and are present in virtually all aquatic habitats1. Diatoms are believed to be derived from a secondary endosymbiotic process, between a heterotrophic eukaryotic cell, a red alga and possibly a green alga1,2,3. As a consequence of their evolutionary history, diatoms have unique biochemical pathways, such as the presence of a urea cycle, that is absent in other photosynthetic organisms4 and different regulatory mechanisms5,6. These novel metabolic capacities are likely to be one of the reasons for the ecological success of this group of algae.

The concentration of CO2 in marine habitats is about 16 μM. This is lower than the KM of the primary carboxylating enzyme, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), that varies from 20 to 70 μM in diatoms7,8, and so may limit their photosynthesis. To circumvent this problem, diatoms have carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) that elevate the CO2 concentration in the vicinity of the active site of Rubisco8. Different types of CCM are present in diatoms. In many species, the expression and/or activity of carbonic anhydrases (CAs) increase at low CO2 concentration9,10,11,12. Phaeodactylum tricornutum, a marine pennate diatom, has CO2/bicarbonate transporters13 and the genes encoding these transporters are also present in the genome of Thalassiosira pseudonana, a marine centric diatom4. In Thalassiosira weissflogii, there is evidence for a biochemical CCM, C4 metabolism but in other diatoms, different approaches, including 14C labeling14,15, protein localization16, transcriptomic17,18, enzyme measurements12 and proteomics18 have produced contradictory results.

Transcriptomic and proteomic approaches are powerful tools to understand the strategies used by diatoms that allow them to thrive in different environments, and have been used to study a number of species19,20. Among marine diatoms, T. pseudonana, and P. tricornutum are good models for these studies since their genome has been sequenced and annotated4,21. The response of T. pseudonana to nitrogen starvation was analysed using proteomics and shown to be different to that of the higher plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, and the green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii22. In contrast, the increase of Krebs cycle enzymes under nitrogen starvation was similar in the diatom and in the cyanobacterium, Prochlorococcus marinus22. Proteomic and transcriptomic approaches have also been applied to study the effect of iron23,24, phosphorus19,25, light fluctuation26, silicate starvation27, oxidative stress28 and multiple stresses29.

Transcriptomic and proteomic studies that analyzed responses of diatoms to changes in CO2 concentration are relatively sparse even though inorganic carbon is a major resource for them. For example, when P. tricornutum was grown at elevated concentrations of bicarbonate, genes encoding carbonic anhydrase and bicarbonate transporter were up-regulated and lipid synthesis genes were down-regulated30. Proteomic analysis of T. pseudonana grown at different CO2 concentrations were used to propose a biochemical model for C4 photosynthesis and also showed that at low CO2, CA and other proteins involved in the CCM increased18.

The aim of this study was to understand more broadly how the proteome and the metabolism of T. pseudonana respond to low CO2 concentration. In order to compare the proteome of T. pseudonana exposed to different concentrations of CO2, one-dimensional gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis (2D-DiGE) followed by mass spectrometry were performed. In parallel, transcriptional changes and enzyme activities were analysed.

Results

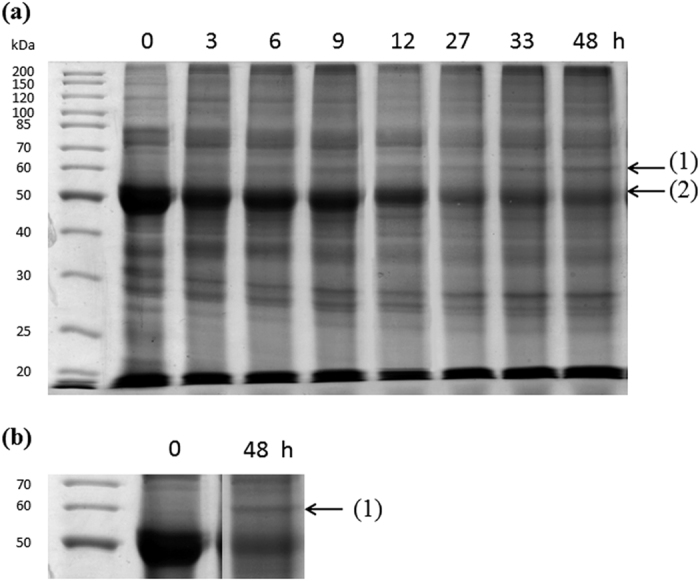

Detection, identification and quantification of a protein expressed at low CO2

Proteins in the crude extract obtained at different times after switching cells from high to low CO2 were analysed by one dimensional SDS-PAGE. There were no striking changes in protein expression, apart from a decrease of the large subunit of Rubisco (arrow 2, Fig. 1) and an increase of a protein with a molecular mass of about 60 kDa (arrow 1, Fig. 1) that was detected approximately 6 h after the switch (Fig. 1). This protein was also present at 400 ppm (data not shown).

Figure 1. Changes in proteins from cells of T. pseudonana shifted from 20,000 to 50 ppm CO2 over 48 hours.

(a) Proteins extracted at different times after switching the cells from 20,000 to 50 ppm CO2 were run on 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. The first lane corresponds to molecular mass markers (Euromedex), and the other lanes correspond to proteins (20 μg) extracted at the times indicated. The arrows (1) and (2) indicate the position of the LCIP63 and Rubisco large subunit, respectively. (b) Close-up of the gel at the molecular mass of LCIP63 for the control and after 48 h treatment at low CO2.

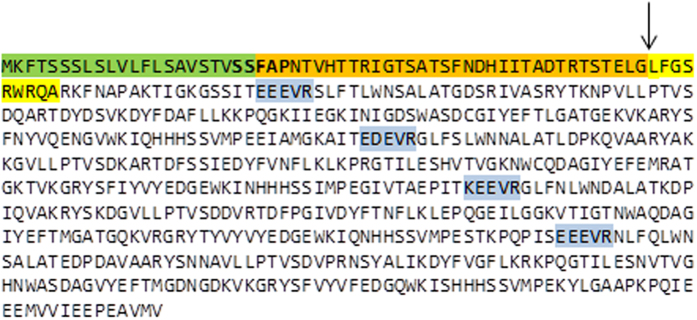

The band at about 60 kDa induced at low CO2, and also the slice of gel at the same position from the extract at high CO2, but without a band (control), were excised and analysed using mass spectrometry. Using GENSCAN software (http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html), a sequence corresponding to the protein induced by low CO2 with a molecular mass of 68.7 kDa was recovered (Fig. 2). This protein was identified with a high sequence coverage (58%) and a very high score (Protein Lynx Global Server (PLGS):16,400). The difference between the molecular mass estimated from the gel, of about 60 kDa, and the theoretical molecular mass of 68.7 kDa estimated from the genome, resulted from the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide (of about 6.0 kDa) cleaved in the mature protein. N-terminal sequencing identified the first nine amino acid residues from the mature protein, starting at LFGSR (Fig. 2, yellow), resulting in a theoretical molecular mass of 62.7 kDa. Therefore the protein is referred to as a Low CO2 Inducible Protein of 63 kDa hereafter called LCIP63. This confirmed that the 68.7 kDa protein sequence contains an N-terminal endoplasmic reticulum peptide signal of 22 amino acid residues (Fig. 2, green) and a chloroplast transit peptide of 34 amino acid residues (Fig. 2, orange; confirmed using Hectar software) and consistent with the transit peptide sequences for diatoms found before31,32. Sequence analysis of LCIP63 revealed four COG4875 related domains (uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria with a cystatin-like fold) which are similar to Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II Association Domain (CaMKII_AD; Supporting data, Fig. S1). This protein sequence was also found in other marine diatoms, for example, Thalassiosira oceanica (four domains), Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries (three domains) and P. tricornutum (two domains) (Supporting data, Figs S2 to S4).

Figure 2. Sequence of LCIP63 identified in the genome of T. pseudonana.

The 68.7 kDa protein sequence contains an endoplasmic reticulum signal peptide of 22 amino acid residues (in green), a chloroplast signal peptide of 34 amino acid residues (in orange) and the mature protein, the first nine amino acid residues of which were identified using N-terminal sequencing (in yellow), the arrow indicates the start of the mature protein. The sequence contained four COG4875 domains (see text), the start of which is highlighted in blue.

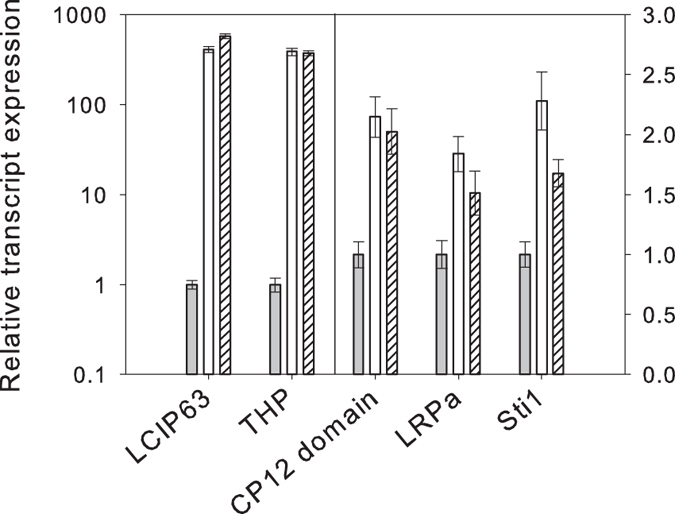

RNA extraction followed by qPCR confirmed that the mRNA of LCIP63 was strongly up-regulated under low CO2 (Fig. 3) in contrast to the housekeeping gene for actin that did not change. In order to check if the response was related to carbon availability, rather than pH, cells were switched from high to low CO2 concentration while maintaining pH between 7 and 7.5 with 10 mM HEPES buffer. Transcript levels of LCIP63 were again highly upregulated (data not shown), suggesting that the response is directly triggered by low CO2.

Figure 3. Relative transcript expression for proteins from cells of T. pseudonana at different CO2 concentrations.

RNA was extracted from cells grown at 20,000 ppm (grey bar), switched to CO2 at 50 ppm for 12 h (white bar) and 24 h (hatched bar). Transcript levels are shown for LCIP63, (corresponding to spots 408 and 172, see Table 1), transmembrane hypothetical protein (THP, spot 696 and 422), “CP12 domain” protein (spot 926), light repressed protein a (LRPT, spot 378) and stress-inducible protein sti1 (spot 549). Error bars represent ± 1 SD.

Analysis by 2D-DiGE of differentially expressed proteins upon a shift to low CO2

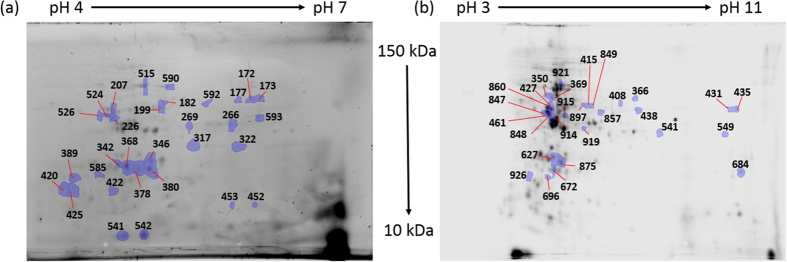

To check whether other proteins were differentially expressed in response to changing CO2 concentration, a more sensitive method than 1D SDS PAGE, 2D-DiGE, was performed using two different gradients (pH 4 to 7 and 3 to 11). Four biological replicates were combined and analysed, before, and 12 hours after, the switch to low CO2. There were statistically significant changes in abundance in low vs high CO2 concentration for 28 spots in each gradient (Fig. 4 and Table 1). These 56 spots were excised and analysed using mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion. The spots corresponded to 42 proteins, of which 16 were more abundant and 26 were less abundant, after the switch to low CO2. These proteins were categorized into 11 groups based on their biological function according to information from NCBI and UniProt (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Differential expression of soluble proteins from T. pseudonana cells at 20,000 ppm and after switching to 50 ppm CO2 for 12 h.

The gels were performed on two gradients of pH 4–7 (a) and pH 3–11 (b). Identification of the spots are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Changes in protein abundance and transcript levels on selected genes after T. pseudonana cells were switched from 20,000 to 50 ppm CO2.

| Accession No. (NCBI) | Accession No. (Swiss Prot) | Gel | Spot ID | Annotation | Functional group | Protein fold change | RNA fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220971674 | B8C995 | 3–11 | 435 | Translation elongation factor alpha | Protein synthesis | 4.11 | − |

| 220973545 | B8C239 | 3–11 | 431 | RL4e, ribosomal protein 4e 60S large ribosomal subunit | Protein synthesis | 3.86 | − |

| 220976737 | B8BTB5 | 4–7 | 422 | Transmembrane hypothetical protein (THP) | Carbon acquisition | 3.71 | 388 |

| 220970433* | B8CCH0* | 4–7 | 172 | LCIP63 | Unknown function | 3.60 | 409 |

| 220969212 | B8CGE1 | 3–11 | 549 | Stress-inducible protein sti1 (BLAST) | Stress | 3.42 | 2.27 |

| 220976737 | B8BTB5 | 3–11 | 696 | Transmembrane hypothetical protein (THP) | Carbon acquisition | 3.41 | 388 |

| 209583601 | B5YLS7 | 4–7 | 368 | Triose-phosphate isomerase | Carbohydrate metabolism | 3.20 | − |

| 220978199 | B8BRE6 | 4–7 | 378 | Light-repressed protein a | Protein synthesis | 2.90 | 1.83 |

| 220969257 | B8CFA9 | 4–7 | 380 | Ascorbate peroxidase | Stress | 2.61 | − |

| 220970433* | B8CCH0* | 3–11 | 408 | LCIP63 | Unknown function | 2.40 | 409 |

| 220972037 | B8C7S8 | 4–7 | 585 | Hypothetical protein THAPSDRAFT_7881 | Unknown function | 2.32 | − |

| 220978087 | B8BQS1 | 3–11 | 926 | Protein with CP12 domain (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | 2.29 | 2.15 |

| 220978087 | B8BQS1 | 4–7 | 425 | Protein with CP12 domain (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | 2.23 | 2.15 |

| 220975793 | B8BX06 | 3–11 | 627 | 14–3–3-like protein | Degradation & signalling | 2.13 | − |

| 220969044 | B8CGL9 | 4–7 | 317 | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase | Photosynthesis | 2.06 | − |

| 220974564 | B8BZK1 | 4–7 | 342 | Phosphomannomutase | Carbohydrate metabolism | 2.06 | − |

| 220976367 | B8BU33 | 3–11 | 875 | Fucoxanthin-chlorophyll a/c light-harvesting protein | Photosynthesis | 1.99 | − |

| 220969044 | B8CGL9 | 3–11 | 541* | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase | Photosynthesis | 1.74 | − |

| 220969727 | B8CEN5 | 4–7 | 389 | Glycoprotein fp21 (BLAST) | Unknown function | 1.67 | − |

| 589908182 | W8VYH0 | 4–7 | 420 | Delta carbonic anhydrase | Carbon acquisition | 1.65 | − |

| 220974490 | B8BZ41 | 4–7 | 266 | Phosphofructokinase | Carbohydrate metabolism | −1.45 | − |

| 224011563 | B5YLQ5 | 3–11 | 366 | Mitochondrial chaperonin | Chaperone | −1.51 | − |

| 125987721 | A0T0R6 | 4–7 | 207 | ATP synthase CF1 beta chain | Energy/ATP | −1.54 | − |

| 209586260 | B5YN92 | 3–11 | 914 | Phosphoglycerate kinase (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | −1.55 | − |

| 220968997 | B8CGK1 | 4–7 | 588 | Glutamine synthetase (BLAST) | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.56 | − |

| 220970599 | B8CCE1 | 4–7 | 322 | Pseudouridylate synthase | Protein synthesis | −1.57 | − |

| 125987749 | A0T0 × 9 | 3–11 | 684 | 30S ribosomal protein S3, chloroplastic | Protein synthesis | −1.58 | − |

| 209586260 | B5YN92 | 3–11 | 915 | Phosphoglycerate kinase (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | −1.60 | − |

| 220976316 | B8BTR4 | 4–7 | 515 | Transketolase | Carbohydrate metabolism | −1.61 | − |

| 220969226 | B8CGI1 | 3–11 | 672 | Demethylmenaquinone methyltransferase (BLAST) | Secondary metabolism | −1.61 | − |

| 220968997 | B8CGK1 | 4–7 | 590 | Glutamine synthetase (BLAST) | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.61 | − |

| 220968642 | B8LCI4 | 4–7 | 593 | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (BLAST) | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.63 | − |

| 220975991 | B8BY55 | 4–7 | 199 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.65 | − |

| 220970584 | B8CCA0 | 4–7 | 269 | Aspartate-ammonia ligase | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.65 | − |

| 209586260 | B5YN92 | 3–11 | 461 | Phosphoglycerate kinase (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | −1.68 | − |

| 220973284 | B8C635 | 3–11 | 369 | Heat shock protein 70 | Chaperone | −1.69 | − |

| 220969617 | B8CET1 | 3–11 | 921 | PEFG, plastid translation factor EF-G (BLAST) | Protein synthesis | −1.70 | − |

| 118411188 | A0T0 × 0 | 3–11 | 427 | 60 kDa chaperonin | Chaperone | −1.71 | − |

| 125987721 | A0T0R6 | 3–11 | 860 | ATP synthase CF1 beta chain | Energy/ATP | −1.76 | − |

| 220977307 | B8BT02 | 4–7 | 233 | Aspartate aminotransferase | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.77 | − |

| 220970665 | B8CCS6 | 3–11 | 438 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.80 | − |

| 118411103 | A0T0N5 | 4–7 | 541 | Rubisco small subunit | Photosynthesis | −1.82 | − |

| 209583569 | B5YLM0 | 4–7 | 182 | Histidinol dehydrogenase | Nitrogen metabolism | −1.82 | − |

| 220977520 | B8BQU2 | 3–11 | 919 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase precursor | Photosynthesis | −1.88 | − |

| 220970292 | B8CDB3 | 3–11 | 857 | Geranylgeranyl reductase (BLAST) | Secondary metabolism | −1.92 | − |

| 220972213 | B8C6C6 | 3–11 | 849 | Mitochondrial ATPase, inner membrane | Energy/ATP | −1.98 | − |

| 118411103 | A0T0N5 | 4–7 | 542 | Rubisco small subunit | Photosynthesis | −2.00 | − |

| 220968222 | B8LDL7 | 4–7 | 592 | N-acetyl-glutamate-gamma-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | Nitrogen metabolism | −2.07 | − |

| 220971973 | B8C8K9 | 4–7 | 526 | RS1, ribosomal protein 1, partial | Protein synthesis | −2.07 | − |

| 209585841 | B5YMV8 | 3–11 | 350 | Regulation, link with ATP synthase (BLAST) | Energy/ATP | −2.19 | − |

| 125987721 | A0T0R6 | 3–11 | 415 | ATP synthase CF1 beta chain | Energy/ATP | −2.22 | − |

| 220977926 | B8BT70 | 3–11 | 847 | Oxidoreductase | Carbohydrate metabolism | −2.28 | − |

| 220977307 | B8BT02 | 4–7 | 524 | Aspartate aminotransferase | Nitrogen metabolism | −2.29 | − |

| 220977307 | B8BT02 | 4–7 | 226 | Aspartate aminotransferase | Nitrogen metabolism | −2.56 | − |

| 209586260 | B5YN92 | 3–11 | 848 | Phosphoglycerate kinase (BLAST) | Photosynthesis | −2.66 | − |

| 220972213 | B8C6C6 | 3–11 | 897 | Mitochondrial ATPase, inner membrane | Energy/ATP | −3.43 | − |

The proteins highlighted in this study were selected stringently by combining different criteria: the highest confident peptide spectral matches obtained by mass spectrometry, and by matching experimental isoelectric points, and molecular masses to theoretical values.

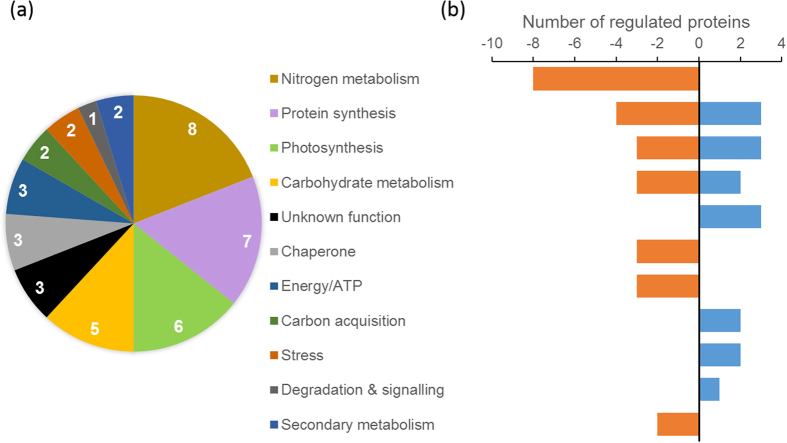

Figure 5. Protein regulation in T. pseudonana for different functional categories on a switch from 20,000 to 50 ppm CO2 for 12 hours.

(a) Number of differentially expressed proteins by functional category, (b) number of proteins classified by functional category that increased (blue) or decreased (orange).

One δ carbonic anhydrase increased after the switch to low CO2 (Table 1). Another protein (Transmembrane Hypothetical Protein, THP) also increased after the switch to low CO2. It was identified using BLAST as a possible carbonic anhydrase though it did not bear the active site of this enzyme but only the transmembrane sequence. The mRNA expression for this protein also increased (Fig. 3).

Six proteins were found that are involved in photosynthesis (Table 1). Three of these are involved in the Calvin-Benson cycle and decreased on transfer to low CO2: the small subunit of Rubisco (in agreement with the pattern of the large subunit observed by SDS-PAGE), a predicted protein identified by BLAST as the chloroplast phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and the chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GAPDHNADPH. In contrast, ferredoxin-NADP reductase, the enzyme that catalyzes the last step of the primary phase of photosynthesis and produces NADPH, was more abundant after transfer to low CO2 (Table 1). Besides these enzymes, two proteins were also more abundant, a protein that possesses a CP12 domain and the mRNA expression of which also increased (Fig. 3) and a fucoxanthin-chlorophyll a/c light harvesting protein (Table 1).

Two proteins that are believed to be involved in stress responses were more abundant after transfer to low CO2: an ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and a predicted protein that could be a stress inducible protein named sti1 (Table 1). The expression of the mRNA encoding for the sti1 protein was checked and was also shown to be up-regulated (Fig. 3).

Three proteins that are involved in energy/ATP metabolism were less abundant after transfer to low CO2 (Table 1). These comprised two ATP synthases (one localized in the mitochondrion) and a predicted protein (regulation linked with ATP synthase). Three proteins classified in the carbohydrate metabolism group were less abundant after the transfer to low CO2: phosphofructokinase (PFK) from glycolysis, transketolase from the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway and an oxidoreductase. Meanwhile triose phosphate isomerase, also belonging to the carbohydrate metabolism group, increased.

Three chaperones (heat shock protein 70, 60 kDa chaperonin and mitochondrial chaperonin), as well as two proteins involved in secondary metabolism, were less abundant after transfer to low CO2 (Table 1). Two proteins involved in degradation and signaling increased after transfer to low CO2.

Four proteins involved in protein synthesis decreased while three others increased after the transfer to low CO2 (Table 1). Eight proteins involved in nitrogen metabolism including glutamine synthase, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase and S-adenosyl methionine synthase, were less abundant after the transfer to low CO2. Three proteins that increased after the transfer to low CO2 were classified as proteins with unknown function, including LCIP63, found previously in the SDS-PAGE experiment (Fig. 1).

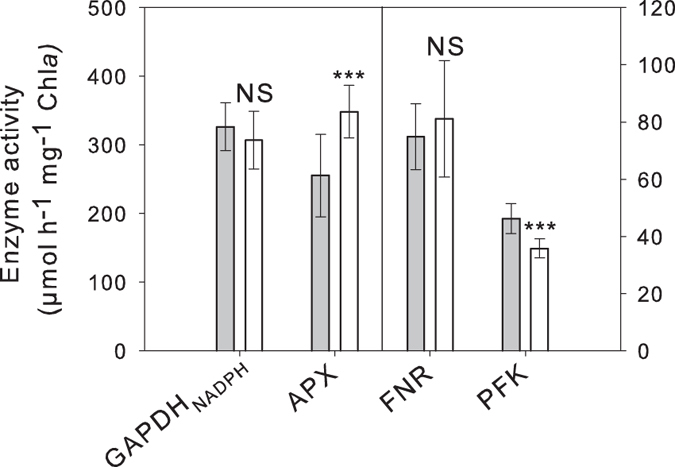

Enzyme activity

To complement the 2D-DiGE results, the activity of four enzymes was measured on proteins extracted from cells grown at 20,000 ppm and 12 h after a switch to 50 ppm CO2 (Fig. 6). The changes in activity were consistent with the expression pattern observed using 2D-DiGE for APX and PFK since their activity increased by a factor of 1.36 (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001) and decreased by 1.29-fold (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001) respectively. However, FNR and GAPDHNADPH activities were not statistically affected by the switch while in the 2D-DiGE experiments, the expression of FNR increased by 2.06-fold and that of GAPDH decreased by 1.88-fold.

Figure 6. Enzyme activities from T. pseudonana at 20,000 and 50 ppm CO2.

Activities of NADPH-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHNADPH), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), ferredoxin NADP reductase (FNR) and phosphofructokinase (PFK) from cells grown at 20,000 ppm CO2 (grey bar), and after a shift to 50 ppm CO2 for 12 h (white bar). Error bars represent ± 1 SD. NS, not significant; ***P < 0.001.

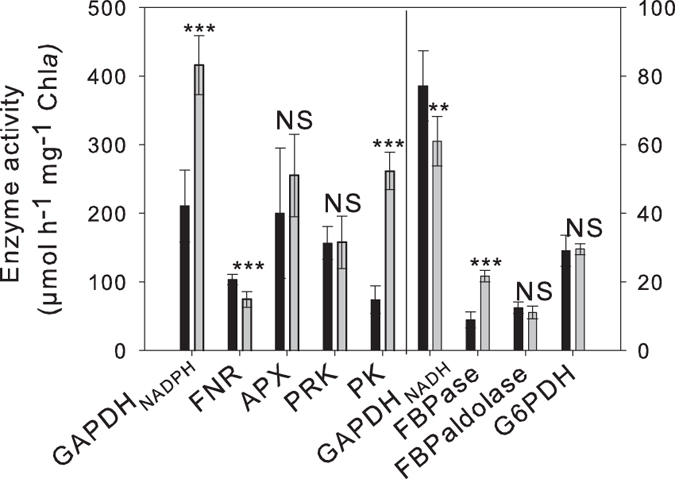

Enzyme activities were also measured from cells acclimated to steady-state conditions at 20,000 and 400 ppm CO2 (Fig. 7). The activity of GAPDHNADPH from the Calvin-Benson cycle was 1.97-fold lower at 400 ppm than at 20,000 ppm CO2 (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001) while the activity of FNR was 1.15-fold higher at 400 ppm than at 20,000 ppm CO2 (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001). At 400 ppm, the activity of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) was 2.42-fold lower (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001) than at 20,000 ppm and the activity of pyruvate kinase (PK), a glycolytic enzyme that provides pyruvate to the Krebs cycle, was also lower (3.52-fold, Student’s t-test, P < 0.001). In contrast, the glycolytic GAPDHNADH, was 1.26-fold higher (Student’s t-test P < 0.01, P = 0.0016) at 400 than at 20,000 ppm. There were no significant differences in the activity of the other enzymes: phosphoribulokinase (PRK), fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) aldolase, APX, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH).

Figure 7. Enzyme activities from T. pseudonana grown at 20,000 and 400 ppm CO2.

Activities of chloroplastic NADPH-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHNADPH), ferredoxin NADP reductase (FNR), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), phosphoribulokinase (PRK), pyruvate kinase (PK), NADH-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDHNADH), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), FBP aldolase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) from cells grown in 400 ppm CO2 (black bars) and 20,000 ppm CO2 (grey bars). Error bars represent + 1 SD. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

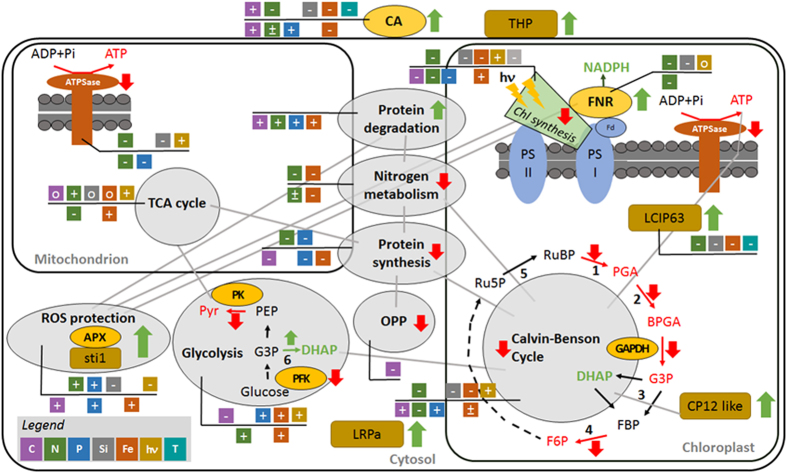

A holistic analysis was developed here using a range of approaches, to understand how the metabolism of T. pseudonana changes on transfer from high to low CO2. These changes, as well as those found in the literature for other stresses, are summarized in Fig. 8. The induction of a CCM under low CO2 is a well-known phenomenon that has both costs and benefits33, and therefore is strongly and rapidly regulated by growth conditions34. CA is very commonly more abundant at low CO2 in diatoms9,10,11,18,35, including T. pseudonana (this study and others9,10,12,18), green algae such as C. reinhardtii36 and cyanobacteria37. In our study, no CO2/bicarbonate transporters were regulated, as previously observed18, indicating that they play a less important role than CA in T. pseudonana in contrast to P. tricornutum13, C. reinhardtii38 and cyanobacteria37. Confirming our previous study12 but in contrast to a previous report18, we did not observe any changes in the abundance of enzymes involved in C4 metabolism.

Figure 8. Schematic diagramme summarising the changes in T. pseudonana metabolism in response to limitation by inorganic carbon and other resources.

Pathways are shown by grey circles and the component enzymes are shown as: 1, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase; 2, phosphoglycerate kinase; 3, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase; 4, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase; 5, phosphoribulokinase; 6, triose-phosphate isomerase. The abbreviations used are: ADP, Adenosine diphosphate; APX ascorbate peroxidase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ATPSase, ATP synthase; BPGA, 1,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid; CA, carbonic anhydrase; Chl, chlorophyll; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; Fd, ferredoxin; FNR, ferredoxin-NADP reductase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; G3P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; hv, light; LCIP63, low CO2 inducible protein 63 kDa; LRPa, light-repressed protein a; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced); OPP, oxidative pentose phosphate pathway; PEP, phosphoenol pyruvate; PFK, phosphofructokinase; PGA, 3-phosphoglyceric acid; Pi, inorganic phosphate; PK, pyruvate kinase; PSI, photosystem I; PSII, photosystem II; Pyr, pyruvate; Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; RuBP, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate; Sti1, stress-inducible protein sti1; THP, transmembrane hypothetical protein. Changes in protein level in response to CO2-limitation are shown as increases (green arrows) or decreases (red arrows). Major interactions between the pathways and organelles are shown by grey lines. Also shown, as coloured boxes adjacent to proteins or pathways, are changes reported in the literature using proteomic or transcriptomic approaches in response to starvation by inorganic carbon (lilac) for T. pseudonana18; nitrogen (green) for T. pseudonana22,29, for P. tricornutum50; phosphorus (blue) for T. pseudonana25, for P. tricornutum19; silica for T. pseudonana (grey)29; iron (russet) for T. pseudonana29, for P. tricornutum46,48,49; fluctuating light (yellow-brown) for T. pseudonana26; temperature (turquoise) for T. pseudonana22,29. Responses for T. pseudonana (above the line) and for P. tricornutum (below the line) are denoted as an increase (+), decrease (−), both decrease and increase (±), no change (o). If the response is not commented on in the paper or if it is not obvious from Supplementary Information, no information is presented.

Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes were less abundant when T. pseudonana cells were switched from high to low CO2. The small and the large subunit of Rubisco were less abundant which is in agreement with the changes of Rubisco activity obtained previously12. It is also consistent with the decrease of the 60 kDa chaperonin, shown here, a protein involved in Rubisco assembly, and with the lower Rubisco transcripts in P. tricornutum at 5 vs 15 mM bicarbonate30. In contrast, regulation of Rubisco is different in cyanobacteria. Rubisco was more abundant in Synechocystis PCC 6803 in air CO2 than in 3% CO237 while no regulation was found when Microcystis aeruginosa cells were switched from 200 to 1,450 ppm39. These results indicate that diatoms may have developed strategies to cope with low CO2 that differ from cyanobacteria. This may be a consequence of the cyanobacterial CCM that involves polyhedral bodies, carboxysomes, that encapsulate Rubisco within a selectively permeable protein shell and simultaneously a CA for CO2 supply from a cytoplasmic bicarbonate pool40.

Other enzymes involved in the Calvin-Benson cycle were also differentially expressed. The observed decrease of NADPH-dependent GAPDH (GAPDHNADPH) at the protein level after the switch to low CO2, and the decrease in its activity at 400 ppm vs 20,000 ppm, are in good agreement with the lower GAPDH transcripts in P. tricornutum at 5 vs 15 mM bicarbonate30 and with GAPDHNADPH activity changes in the freshwater diatom A. formosa41. Similarly, the chloroplastic PGK was less abundant after the CO2 switch to 50 ppm. PGK is involved in glycolysis and in the Calvin-Benson cycle, but the presence of the ASAF sequence31,32 at the start of the identified protein indicates that it was the chloroplastic isoform of PGK that responded. This result has not been found previously but is consistent with the down-regulation of other Calvin-Benson enzymes such as FBPase18. A protein, with a CP12 domain was more abundant and its transcript level was higher at low vs high CO2. Though CP12 proteins42 are widely studied for their role in photosynthesis, acting as assemblers for the GAPDH/PRK/CP12 complex43,44 and inhibiting these two Calvin-Benson enzymes within the supramolecular complex, they also play many other roles in plants, green algae and very likely in diatoms45,46. The increase in the protein with the CP12 domain may therefore represent an additional way of down-regulating the Calvin-Benson cycle, helping to match its activity to the CO2 supply (Fig. 8).

The tricarboxylic acid cycle, chrysolaminarin and lipid synthesis were not affected by short-term carbon limitation as was observed under nitrogen limitation22. In contrast, the glycolytic pathway was affected by the switch to low CO2. There was a decrease in activity of pyruvate kinase, a key enzyme of this pathway, and in the activity and abundance of PFK in agreement with Kutska et al.18. In contrast, triose phosphate isomerase expression increased at low CO2 which has been found before in plants under water stress47. Glycolytic metabolism increased in response to all other stresses in both T. pseudonana and P. tricornutum (Fig. 8). As has been found before18, an enzyme involved in the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, transketolase, was less abundant which may reduce the availability of ribose, an intermediate required for nucleic acid synthesis. This is consistent with the decrease in protein synthesis (Fig. 8).

Changing the CO2 supply to T. pseudonana has a large effect on metabolic pathways other than those related to carbon. Indeed, the switch to low CO2 had a negative impact on proteins involved in nitrogen metabolism as in T. pseudonana and P. tricornutum exposed to iron and nitrogen starvation (Fig. 8 29,48,49,50). The decrease of proteins involved in nitrogen metabolism under low CO2 may be related to the homeostasis between carbon and nitrogen as shown in the higher plant, Arabidopsis thaliana51 and in diatoms22.

Overall, there is a decrease in many metabolic pathways under carbon limitation and this is also evidenced by the decrease in ATP synthase in both mitochondria and chloroplasts. This may result in a mismatch between energy production and the metabolic demand that in turn, may increase the risk of oxidative damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. To limit the damage, a number of changes are triggered. For instance, geranylgeranyl reductase, that catalyzes the most critical step in chlorophyll synthesis, was less abundant at low CO2 which may reduce ROS production by reducing light harvesting and electron pressure. Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR), that produces NADPH in the last step of the primary phase of photosynthesis, was more abundant after the switch to 50 ppm CO2. This could increase the supply of NADPH, a reducing agent involved in protecting cells against ROS. Lastly, an increased abundance of ROS scavenging enzymes is a common response to oxidative stress. Indeed, the activity and abundance of APX increased after the switch to low CO2. The abundance and transcript level of another stress-responsive protein, sti1 was also higher as also observed under salt stress52. Moreover, as a consequence of carbon limitation, there was an increase of proteins involved in degradation and signaling, such as 14–3–3 proteins, multitasking proteins involved in the response of plants to many environmental stresses53,54. An increase in protein degradation has also been observed in P. tricornutum under different stresses (Fig. 8).

A protein found here, named LCIP63, increased substantially at the protein and transcript level when cells were grown at 400 ppm or switched to 50 ppm CO2. This protein was reported in a previous work as a “CaMKII associated domain containing protein” (SI Table 629) but was not discussed. We analysed the sequence of this protein and found four COG4875 domain repetitions, similar to Ca2+/calmodulin activated protein kinase II (CaMKII)_association domain (AD). This domain is a C-terminal region of approximately 140 residues found in CaMKII that is responsible for holoenzyme oligomerization55. CaMKIIs are calmodulin-dependent protein kinases that are able, via their calmodulin (CaM) binding domain, to respond to calcium ions (Ca2+). Calcium ions are secondary messengers involved in many signalling pathways and in the response of cells to changing conditions in plants, macroalgae and diatoms49,56. Calmodulin is present in the chloroplasts of higher plants57, where it plays a role in the regulation of photosynthesis in response to light58, and CaMKIIs are present in green algae59 and in the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium60 that is, like diatoms, a member of the chromalveolates. Although the function of LCIP63 is presently unknown, the presence of a chloroplast signal peptide strongly suggests that it is located in the chloroplast because signal peptides in diatoms are very well defined31,32. Moreover in response to silicate, iron, nitrogen and temperature stress, this protein (Joint Genome Institute protein ID 264181) was less abundant, among the most affected proteins (up to 9-fold, SI Table 629) and did not change under low CO2 probably because it was already present in the control treatment that was 400 ppm29. These different patterns suggest that LCIP63 is not involved in responses to general stress but instead is specifically present when CO2 is limited. The sequence of LCIP63 was also found in the genome of T. oceanica, P. multiseries and P. tricornutum, suggesting that it might play a widespread role in the responses of diatoms to low CO2.

To conclude, the response of diatoms to an individual stress requires many metabolic pathways to be altered in a co-ordinated way. In this study on carbon limitation (Fig. 8), these responses act to: (i) increase acquisition mechanisms for the limiting resource (e.g. CA increase), (ii) match the expense of the metabolic pathways to the requirement (e.g. a reduction in the Calvin-Benson cycle and protein synthesis), (iii) redirect resources (e.g. protein degradation to recycle nitrogen and carbon), (iv) minimise damage caused by excess light energy (e.g. by reducing light acquisition and stimulating ROS scavengers), and (v) co-regulate the metabolic pathways (e.g. homeostasis between carbon and nitrogen). These responses appear to be common to different stresses such as nutrient limitation (nitrogen, phosphorus, silica, iron) or temperature decrease and fluctuating light (Fig. 8). Under those stresses, there is a tendency, in T. pseudonana, for protein, chlorophyll and ATP synthesis to be down-regulated, protein degradation, glycolysis and ROS protection to be up-regulated and for the tricarboxylic acid cycle to be unaffected (Fig. 8). Furthermore, where a comparison can be made, the responses of T. pseudonana and P. tricornutum are broadly similar. Mechanisms are required to choreograph these changes. LCIP63, described here, could take this role for carbon stress since it contains a domain for a signaling protein, Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II, and responded similarly to carbonic anhydrase, which is a marker for carbon-limitation. The role of LCIP63 in carbon-limitation is further supported by results in SI Table 629 since it was less abundant under nitrogen, phosphorus and iron limitation and low temperature: conditions that minimise carbon limitation. However, the precise mode of action of this protein remains to be elucidated.

While up to now work has mainly been focussed on individual stresses in the real world diatoms are likely to experience multiple stresses. The co-ordinated response of many metabolic pathways to a single stress, shown here and elsewhere, strongly indicates that in the future diatoms should be challenged with multiple stresses in order to obtain a clearer picture of how they respond to their changing environment.

Methods

Strain, media and culture conditions

Thalassiosira pseudonana, (CCAP 1085/12; equivalent to CCMP1335), was grown in artificial sea water and F/2+ Si medium at 16 °C under continuous illumination at 50 μmol photon m−2 s−1, photosynthetically active radiation, as described earlier12. Cultures were grown at steady-state CO2 concentrations of 20,000 or 400 ppm. In ’switch’ experiments, cells grown at 20,000 ppm were transferred to 50 ppm for different lengths of time. Cultures were bubbled at a gas flow rate of 130 mL min−1.

Protein extraction and identification by mass spectrometry of LCIP63

Soluble protein extracts were prepared as described previously5,61 in a buffer containing 30 mM Tris, 4 mM EDTA (called TA buffer), 1 mM NAD, 20% glycerol and 40 μg mL−1 protease inhibitor (Sigma). The protein concentration was assayed using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) reagent using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Extracts were incubated for 15 min at 80 °C with 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 0.2 M Tris and 0.05% bromothymol blue. Protein migration was performed on 12% polyacrylamide gel Mini-PROTEAN® Tetra Cell (Biorad, Hercules, USA). Gels were either stained with Coomassie blue to determine any differential pattern at low and high CO2 or the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, stained with red Ponceau, and used for N-terminal sequencing. LCIP63 was identified using a Synapt G1 mass spectrometer (Waters, Manchester, UK) coupled to a nano flow UPLC nanoAcquity (Waters). Spectra and protein search were processed by the PLGS 3.0.1 software (Waters) with the same search parameters as described below. N-terminal sequence determination was performed by Edman degradation using an automatic sequencer (Procise 494, Applied Biosystems). Mature sequence of LCIP63 was analysed using Hectar (http://webtools.sb-roscoff.fr/) to identify the location of the protein.

RNA quantification

T. pseudonana cells were centrifuged at 3,720 g for 10 min at 4 °C, frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. 100 mg of cells, were incubated with 4 mL of Trizol® reagent (ThermoFisher scientific, Waltham, USA), for 5 min and 800 μL of chloroform (Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) was added. The mixture was shaken for 10 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. To 600 μL of the aqueous phase, 375 μl of RNA dilution buffer (SV total RNA isolation system, Promega, Madison, USA) was added, mixed and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 10 min. 250 μL of 90% cold ethanol was added to the supernatant and next step performed from step 7 onwards following manufacturer’s SV total RNA isolation system kit protocol (Promega, Madison, USA). Isolated RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically at 260 nm (NanoDrop 2000c; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80 °C. For cDNA synthesis, 175 ng total RNA and 0.5 μg random primers (Promega) were used with the GoScript™ Reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses were performed on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA). The reaction volume was 15 μL and the final concentration of each primer was 0.5 μM. The cycling parameters of the qPCR were 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 45 cycles of 98 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 10 s. A final melting curve from 65 °C to 95 °C was performed to determine the specificity of the amplification. To determine the amplification kinetics of each product, the fluorescence derived from the incorporation of EvaGreen into the double-stranded PCR products was measured at the end of each cycle using the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix 2X Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The results were analysed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager software, version 3.0 (Bio-Rad, USA). The RNA actin gene was used as a normalization reference. For each point, a technical duplicate and biological triplicate was performed. The amplification efficiencies for each primer pairs were between 75 and 100%. All of the primer pairs used for qPCR are reported in Table S1.

2D-DiGE and mass spectrometry analysis

All samples (150 μg) were washed with the 2D-Clean-up kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and solubilized in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, pH 8.5 without DTT and carrier ampholytes) to a final concentration of 2.5 μg μL−1. 50 μg of protein were labeled using 400 pmol of the dye following GE Healthcare protocol. The samples were vortexed and incubated for 10 min in the dark. Labeled samples were then combined, and 65 μM DTT (final concentration) was added. The samples were vortexed and kept for 10 min on ice in the dark. The combined samples were supplemented with an equal volume of double strength lysis buffer with IPG Buffer pH 4–7 or pH 3–11 (GE Healthcare) and then supplemented with Destreak Rehydration Buffer containing 0.5% (v/v) IPG buffer pH 4–7 to a final volume of 200 μL.

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed on a mixture of 150 μg of protein per gel (50 μg for each treatment plus 50 μg of standard) using 11 cm gels with an immobilized linear pH gradient of 4–7 or 3–11 (Immobiline DryStrips, GE Healthcare) on an IPGphorIII machine (GE Healthcare). IEF was performed at a 300 V gradient for 1.5 h, a 1,000 V gradient for 1.5 h, a 6,000 V gradient for 2.5 h and a 6,000 V step for 2 h at 20 °C. Prior to SDS PAGE, IPG strips were equilibrated for 10 min in 6 M urea, 50 mM Tris pH 8.8, 2% SDS, 38.5% glycerol and 65 mM DTT, followed by 10 min with 2% iodoacetamide instead of DTT. The second dimension was performed using a Criterion Dodeca Cell separation unit (Biorad) and precast criterion TGX at 17 °C. IPG strips were placed on the top of the precast gels, overlaid with 0.5% agarose in 2x TGS running buffer (Biorad) containing bromophenol blue. Gels were run at 20 °C using TGS 1x running buffer. Electrophoresis was conducted at 50 V for 5 h. After SDS-PAGE, cyanine dye-labeled protein gels were scanned directly using the EDI scanner (GE Healthcare) at a resolution of 50 μm. After fluorescence imaging, gels were washed for 10 min in ultrapure water and post-stained with the ImperialTM Protein Stain (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). The Samespot software package (version 4.0.3; nonlinear dynamics) was used to determine protein abundance and statistics based on 2D-DiGE. Based on Samespot analysis, spots of interest were excised using a Shimadzu Biotech Xcise System (Champs sur Marne, France) and submitted to trypsin digestion after reduction and alkylation. Tryptic peptides were analysed on a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to a nano liquid chromatography (Ultimate 3000, Dionex). Briefly, peptides were separated by a 30 min-linear gradient of 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid in water, on a reversed phase C18 column, and were detected on the mass spectrometer in a positive ion mode, alternating a scan event full MS in the Orbitrap analyser at 70 000 resolution in a 350–1900 m/z range with scan events of MS/MS (Top 10), in the Higher Energy Collisional Dissociation cell at 17 500 resolution in a 200–2000 m/z range. For mass spectra processing and protein searches, Proteome Discoverer (version 2.1.0.81, ThermoFisher) was used and the raw files generated from the MS/MS analyses were searched with Sequest HT and Mascot search engines. Search parameters were: T. pseudonana extracted from the protein database NCBI (ID 35128, 24,090 entries); Enzyme trypsin; maximum two miscleavages;carbamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine set as static and dynamic modifications, respectively; precursor and fragment mass tolerance set at ± 5–10 ppm and ± 0.02 Da, respectively. Proteins were identified if 2 unique “rank 1” peptide sequences of more than 6 amino acids passed the high confidence filter, with validation on q-Value (Strict Target FDR: 0.01) and maximum Delta Cn: 0.05 (Sequest HT criteria), or the peptide individual score was above 20 and p < 0.05 (Mascot criteria).

Enzyme activities measurement

Enzyme activities were measured using extracts from exponentially growing cells. The soluble protein extracts were prepared as described in Erales et al.61 and Mekhalfi et al.5 in the TA buffer containing 0.1 mM NAD and 1 mM cysteine. Activities were measured from the rates of appearance or disappearance of 0.2 mM NADH or NADPH at 340 nm at room temperature (20 to 25 °C). All biochemicals were obtained from Sigma Inc (Saint Louis, MO, USA). GAPDHNADPH and GAPDHNADH were measured as described in Graciet et al.62. Soluble protein extracts were also incubated with 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and/or 1 mM NADPH for 10 min. PRK was measured as described previously63. PFK, G6PDH, and Ferredoxin NADP reductase (FNR) was measured as described in Mekhalfi et al.5. PK was measured in the presence of 5 mM PEP, LDH (2 U) and 1 mM ADP and 0.2 mM NADH. FBP aldolase was measured as described in Erales et al.64. Ascorbate peroxidase (AP) was measured in 0.2 M Tris/HCl buffer pH 7.8, in the presence of 0.25 mM ascorbic acid and 0.5 mM H2O2. Activity was monitored at 290 nm using an extinction coefficient of 2.8 mM−1 cm−1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Clement, R. et al. Responses of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana to changes in CO2 concentration: a proteomic approach. Sci. Rep. 7, 42333; doi: 10.1038/srep42333 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to our co-author, colleague and dear friend, Sabrina Lignon, who died at the age of 36, before this work was completed. Romain Clément’s studentship was supported by the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MENRT). Brigitte Gontero’s group is supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Aix-Marseille Université, A*midex project (No. ANR-11-IDEX-0001–02), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Signaux-BioNRJ, ANR-15-CE05-0021-03), the Region PACA and IBiSA. Stephen Maberly’s work is supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council and a visiting scholarship from Aix Marseille Université. We thank Ahmed Zellat for technical support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Design of the experiments: R.C., S.M. and B.G. Involved in 2D-DiGE experiment: M.P. and R.C. Involved in M.S. experiments: P.M. (sequencing), R.L. and S.L. (LC-MSMS). Involved in enzyme activities: E.J. and R.C.; in transcriptomic experiments, Y.D., C.P. and R.C. Analysed the data: R.C., S.M. and B.G. Wrote the paper: R.C., S.M. and B.G. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Armbrust E. V. The life of diatoms in the world’s oceans. Nature 459, 185–192 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa A. et al. Genomic footprints of a cryptic plastid endosymbiosis in diatoms. Science 324, 1724–1726 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps P. & Moreira D. Reevaluating the green contribution to diatom genomes. Genome Biol Evol 4, 795–800 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust E. V. et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science 306, 79–86 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhalfi M. et al. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is regulated by ferredoxin-NADP reductase in the diatom Asterionella formosa. New Phytol 203, 414–423 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm C. et al. The regulation of carbon and nutrient assimilation in diatoms is significantly different from green algae. Protist 157, 91–124 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger M. R. et al. The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can J Bot 76, 1052–1071 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Young J. N. et al. Large variation in the Rubisco kinetics of diatoms reveals diversity among their carbon-concentrating mechanisms. J Exp Bot 67, 3445–3456 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H., Nakatsuma D., Ishida M. & Matsuda Y. Regulation of the expression of intracellular beta-carbonic anhydrase in response to CO2 and light in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Physiol 139, 1041–1050 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawfurd K. J., Raven J. A., Wheeler G. L., Baxter E. J. & Joint I. The response of Thalassiosira pseudonana to long-term exposure to increased CO2 and decreased pH. PLoS ONE 6, e26695 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson B. M., Meile C. & Shen C. Quantification of extracellular carbonic anhydrase activity in two marine diatoms and investigation of its role. Plant Physiol 162, 1142–1152 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement R., Dimnet L., Maberly S. C. & Gontero B. The nature of the CO2-concentrating mechanisms in a marine diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana. New Phytol 209, 1417–1427 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K., Tanaka A. & Matsuda Y. SLC4 family transporters in a marine diatom directly pump bicarbonate from seawater. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 1767–1772 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinfelder J. R., Milligan A. J. & Morel F. M. M. The role of the C4 pathway in carbon accumulation and fixation in a marine diatom. Plant Physiol 135, 2106–2111 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts K., Granum E., Leegood R. C. & Raven J. A. C3 and C4 pathways of photosynthetic carbon assimilation in marine diatoms are under genetic, not environmental, control. Plant Physiol 145, 230–235 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka R., Kikutani S., Mahardika A. & Matsuda Y. Localization of enzymes relating to C4 organic acid metabolisms in the marine diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana. Photosynth Res 121, 251–263 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn P. J. & Morel F. M. M. Expression and inhibition of the carboxylating and decarboxylating enzymes in the photosynthetic C4 pathway of marine diatoms. Plant Physiol 146, 300–309 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustka A. B. et al. Low CO2 results in a rearrangement of carbon metabolism to support C4 photosynthetic carbon assimilation in Thalassiosira pseudonana. New Phytol 204, 507–520 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng T.-Y. et al. Examination of metabolic responses to phosphorus limitation via proteomic analyses in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Sci. Rep. 5, 10373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhseen Z. T., Xiong Q., Chen Z. & Ge F. Proteomics studies on stress responses in diatoms. Proteomics 15, 3943–3953 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C. et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456, 239–244 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockin N. L., Mock T., Mulholland F., Kopriva S. & Malin G. The response of diatom central carbon metabolism to nitrogen starvation is different from that of green algae and higher plants. Plant Physiol 158, 299–312 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C. S. et al. Cellular responses associated with ROS production and cell fate decision in early stress response to iron limitation in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. J Proteome Res 13, 5510–5523 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn B. L. et al. Diatom proteomics reveals unique acclimation strategies to mitigate Fe limitation. PLoS ONE 8, e75653, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075653 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrman S. T. et al. The transcriptome and proteome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana reveal a diverse phosphorus stress response. PLoS ONE 7(3), e33768 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouneva I., Muth-Pawlak D., Battchikova N. & Aro E.-M. Changes in relative thylakoid protein abundance induced by fluctuating light in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. J Proteome Res (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C. et al. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of the metabolism mechanism associated with silicon response in the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. J Proteome Res 13, 720–734 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser S. et al. Mapping the diatom redox-sensitive proteome provides insight into response to nitrogen stress in the marine environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 2740–2745, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319773111.1319773111 [pii] (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock T. et al. Whole-genome expression profiling of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana identifies genes involved in silicon bioprocesses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 1579–1584 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mus F. et al. Physiological and molecular analysis of carbon source supplementation and pH stress-induced lipid accumulation in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97, 3625–3642 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesgen P. F. et al. Proteomic amino-termini profiling reveals targeting information for protein import into complex plastids. PLoS ONE 8, e74483 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian O. & Kroth P. G. Identification and characterization of a new conserved motif within the presequence of proteins targeted into complex diatom plastids. Plant J 41, 175–183 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. A., Beardall J. & Giordano M. Energy costs of carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms in aquatic organisms. Photosynth Res 121, 111–124 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano M., Beardall J. & Raven J. A. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol 56, 99–131 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson B. M., Dupont C. L. & Matsuda Y. The physiology and genetics of CO2 concentrating mechanisms in model diatoms. Curr Opin Plant Biol 31, 51–57 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M., Suzuki I. & Shiraiwa Y. Proteomic analysis of high-CO2-inducible extracellular proteins in the unicellular green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol 52, 1302–1314 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battchikova N. et al. Dynamic changes in the proteome of Synechocystis 6803 in response to CO2 limitation revealed by quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res 9, 5896–5912 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Duanmu D. & Spalding M. Carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: inorganic carbon transport and CO2 recapture. Photosynth Res 109, 115–122 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrini G., Cunsolo S., Schuurmans M., Matthijs H. & Huisman J. Changes in gene expression, cell physiology and toxicity of the harmful cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa at elevated CO2. Frontiers in Microbiology 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae B. D., Long B. M., Badger M. R. & Price G. D. Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol R 77, 357–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhalfi M., Amara S., Robert S., Carrière F. & Gontero B. Effect of environmental conditions on various enzyme activities and triacylglycerol contents in cultures of the freshwater diatom, Asterionella formosa (Bacillariophyceae). Biochimie 101, 21–30 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groben R. et al. Comparative sequence analysis of CP12, a small protein involved in the formation of a Calvin cycle complex in photosynthetic organisms. Photosynth Res 103, 183–194 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graciet E., Lebreton S., Camadro J.-M. & Gontero B. Characterization of native and recombinant A4 glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Eur J Biochem 270, 129–136 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marri L. et al. Spontaneous assembly of photosynthetic supramolecular complexes as mediated by the intrinsically unstructured protein CP12. J Biol Chem 283, 1831–1838 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard T. P., Upton G. J. G., Lloyd J. C. & Raines C. A. Antisense suppression of the small chloroplast protein CP12 in tobacco: A transcriptional viewpoint. Plant Signal Behav 6, 2026–2030 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontero B. & Maberly S. C. An intrinsically disordered protein, CP12: jack of all trades and master of the Calvin cycle. Biochem Soc Trans 40, 995–999 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S. M., Taxak P. C., Jain P. K., Saini R. & Srinivasan R. Glycolytic enzyme activities and gene expression in Cicer arietinum exposed to water-deficit stress. Appl Biochem Biotech 173, 2241–2253 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommer M. et al. Genome and low-iron response of an oceanic diatom adapted to chronic iron limitation. Genome Biol 13, 1–21, doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-7-r66 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. E. et al. Whole-cell response of the pennate diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum to iron starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 10438–10443 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipanah L., Rohloff J., Winge P., Bones A. M. & Brembu T. Whole-cell response to nitrogen deprivation in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Exp Bot 66, 6281–6296 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellero Y., Lamothe-Sibold M., Jossier M. & Hodges M. Arabidopsis thaliana ggt1 photorespiratory mutants maintain leaf carbon/nitrogen balance by reducing Rubisco content and plant growth. Plant J 83, 1005–1018 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosová K., Prášil I. T. & Vítámvás P. Protein contribution to plant salinity response and tolerance acquisition. Int J Mol Sci 14, 6757–6789 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnke P. C. & Ferl R. J. In Annual Plant Reviews: Protein-Protein Interactions in Plant Biology Vol. 77 (eds Michael T. McManus, William A Laing & Andrew C. Allan) 329–329 (Sheffield academic press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhao X., Guo C., Chen L. & Li K. Spinach 14-3-3 protein interacts with the plasma membrane H+ -ATPase and nitrate reductase in response to excess nitrate stress. Plant Physiol Bioch 106, 187–197 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg O. S. et al. Oligomerization states of the association domain and the holoenyzme of Ca2+/CaM kinase II. FEBS J 273, 682–694 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington A. M. & Brownlee C. The generation of Ca2+ signals in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55, 401–427 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A. & Vothknecht U. The role of calcium in chloroplasts. An intriguing and unresolved puzzle. Protoplasma 249, 957–966 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai J. & Johnson C. H. Dark-stimulated calcium ion fluxes in the chloroplast stroma and cytosol. The Plant Cell 14, 1279–1291 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel L.-P., Sheen J. & Séguin A. Ancient signals: comparative genomics of green plant CDPKs. Trends in Plant Sci 19, 79–89 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosic N. et al. Unfolding the secrets of coral-algal symbiosis. ISME J 9, 844–856 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erales J., Gontero B. & Maberly S. C. Specificity and function of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in a freshwater diatom, Asterionella formosa (Bacillariophyceae). J Phycol 44, 1455–1464 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graciet E., Mulliert G., Lebreton S. & Gontero B. Involvement of two positively charged residues of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the assembly process of a bi-enzyme complex involved in CO2 assimilation. Eur J Biochem 271, 4737–4744 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontero B., Cardenas M. L. & Ricard J. A functional five-enzyme complex of chloroplasts involved in the Calvin cycle. Eur J Biochem 173, 437–443 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erales J., Avilan L., Lebreton S. & Gontero B. Exploring CP12 binding proteins revealed aldolase as a new partner for the phosphoribulokinase/glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase/CP12 complex. purification and kinetic characterization of this enzyme from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS J 275, 1248–1259 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.