Abstract

Background

On December 8th, 2015, World Health Organization published a priority list of eight pathogens expected to cause severe outbreaks in the near future. To better understand global research trends and characteristics of publications on these emerging pathogens, we carried out this bibliometric study hoping to contribute to global awareness and preparedness toward this topic.

Method

Scopus database was searched for the following pathogens/infectious diseases: Ebola, Marburg, Lassa, Rift valley, Crimean-Congo, Nipah, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and Severe Respiratory Acute Syndrome (SARS). Retrieved articles were analyzed to obtain standard bibliometric indicators.

Results

A total of 8619 journal articles were retrieved. Authors from 154 different countries contributed to publishing these articles. Two peaks of publications, an early one for SARS and a late one for Ebola, were observed. Retrieved articles received a total of 221,606 citations with a mean ± standard deviation of 25.7 ± 65.4 citations per article and an h-index of 173. International collaboration was as high as 86.9%. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had the highest share (344; 5.0%) followed by the University of Hong Kong with 305 (4.5%). The top leading journal was Journal of Virology with 572 (6.6%) articles while Feldmann, Heinz R. was the most productive researcher with 197 (2.3%) articles. China ranked first on SARS, Turkey ranked first on Crimean-Congo fever, while the United States of America ranked first on the remaining six diseases. Of retrieved articles, 472 (5.5%) were on vaccine – related research with Ebola vaccine being most studied.

Conclusion

Number of publications on studied pathogens showed sudden dramatic rise in the past two decades representing severe global outbreaks. Contribution of a large number of different countries and the relatively high h-index are indicative of how international collaboration can create common health agenda among distant different countries.

Keyword: Bibliometrics, Outbreaks, Virus, WHO, VOSviewer, AcrGIS 10.1

Background

On December 8th, 2015, World Health Organization (WHO) led a meeting of experts and health consultants in Geneva to discuss and publish a priority list of pathogens likely to cause serious outbreaks in the near future bearing in mind that the suggested pathogens had limited or no available effective therapies or preventive measures [1]. The meeting came up with a list of top eight emerging serious pathogens that are of great harmful health consequences. According to WHO, the list is not an ultimate one and is supposed to be reviewed annually to include any new emerging pathogens. The WHO list aims to lay the basis and background for national and international health planning to combat and control any potential outbreaks of these pathogens. Furthermore, the WHO wanted countries, researchers, clinicians, and policy makers to talk about these pathogens and corresponding infectious diseases as part of global awareness and preventive policies which might include developing new and inexpensive diagnostics, therapies, vaccines, and behavioral health measures.

According to WHO, the list of pathogens, which required urgent attention for research and development pertaining to preparedness, included “Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever, Ebola virus, Marburg, Lassa fever, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus diseases, Nipah, and Rift Valley fever” [1]. These infectious diseases are caused by viruses and some of them, such as Crimean-Congo and Ebola, are associated with high fatality rate [2–8]. Marburg virus is transmitted to people from fruit bats and spreads among humans through human-to-human transmission [9–13] while Lassa fever is transmitted to humans through food contaminated with rodent feces or urine [14, 15]. Middle East respiratory syndrome is caused by a coronavirus that was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012 [16–18] while SARS, another coronavirus respiratory disease, was recognized on February 2003 [19, 20]. Nipah virus, identified in 1998, is emerging zoonosis that affects both animals and humans [13, 21–24]. Rift Valley fever is a viral zoonosis that was first identified among sheep on a farm in the Rift Valley of Kenya [25–29]. The WHO committee listed another three pathogens/infectious diseases and considered them as serious and require an action as soon as possible. These three serious diseases include Chikungunya, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, and Zika.

Literature review using Pubmed, Google Scholar and Scopus showed that bibliometric studies on SARS or Ebola or Nipah virus have been carried out, but as a single disease and not as a group of diseases with potential future severe epidemics [25–29]. The collective analysis of literature on top eight pathogens will give a more comprehensive view on these infectious diseases and will help identify which one needs to be given top priority for funding and research.

It has been reported that mapping literature with certain statistical methods could help in detection of emerging infectious disease outbreaks particularly in the presence of internet with thousands of reports being easily communicated among public health specialists and healthcare providers [30, 31]. Based on all of the above, we carried out this bibliometric study to analyze literature on top eight emerging pathogens suggested by WHO. Specifically, information regarding number of publications over time, contribution of various countries, international collaboration, active authors and institutions, journals that are actively publishing articles, citations analysis, geographical distribution of publications, visualization of inter-country collaboration, and top cited articles will be presented. This kind of analysis will be of value to virologists, pharmacist, medicinal chemist, and clinicians who are interested in infectious viral diseases and in developing effective preventive and curative pharmaceutical products. Young researchers need to direct their research efforts toward emerging diseases because they are considered top priority and a bulk of financial support will be invested in these diseases. Healthcare workers in the field of travel medicine need to be aware of the map of infectious diseases that quickly cross borders from one country to another leading to spread of diseases with potential negative impact on public health and tourism industry.

Methods

For this study, Scopus search engine was chosen to retrieve required literature. Scopus was used because of its advantages over other databases such as Web of Science (WoS), Google scholar or Pubmed [32]. According to Falagas et al. study, no database is perfect and each has certain merits over the other. For example, PubMed and Google Scholar are free to use in contrast to Scopus and WoS. PubMed lacks citation analysis in contrast to other databases. Scopus offers about 20% more coverage than Web of Science and 100% of Medline database is covered by Scopus. Google Scholar is the largest in terms of coverage but results obtained by Google Scholar have inconsistent accuracy. Although Scopus covers a wider journal range, it is currently limited to articles published after 1995 when compared with WoS [32]. In the current study, we preferred the use of Scopus because of its wider coverage since we are interested in global research activity in the eight emerging pathogens. Many of the journals published from developing countries, where these infectious diseases were found, are indexed in Scopus. This is reflected in the number of journals covered by Scopus versus those covered by WoS [32].

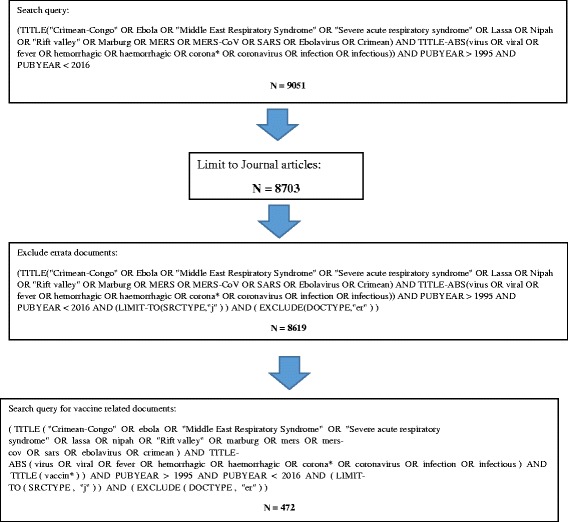

In the current study, keywords used were the names of diseases that appeared in the WHO top eight list. To avoid errors, the names of diseases were followed by conditional keywords such as “virus OR viral OR fever OR hemorrhagic OR haemorrhagic OR corona* OR coronavirus OR infection OR infectious). Fig. 1 illustrates the steps followed along with keywords and search query used in Scopus to retrieve required data.

Fig. 1.

Strategy and search query used to retrieve required data in Scopus

The data obtained were refined using the side functions in Scopus. Such functions include: 1) time limitation which was set for this study from 1996 to 2015, 2) source type of data which was set in this study to be journal articles while books and book chapters were excluded, and finally 3) type of documents and for the purpose of this study all types of documents were included except errata (correction).

Analysis of data was carried out using the “analyze” function in Scopus menu bar. Analysis included annual number of published documents, productivity of each country, author, preferred journals for publishing research on top eight emerging pathogens, geographical distribution, network visualization, and institution/organization. Scopus allows for citation analysis such as total number of citations, Hirsch index (h-index), and top cited articles. The h-index is a parameter used to measure productivity and scientific impact of an author, institution, or country, or even a subject area [33]. Scopus can also give analysis about active journals in publishing articles on studied diseases. Active journals were presented along with Impact Factor (IF) which was obtained from the Journal Citation Report published by Thomson Reuters.

An important feature in Scopus is that it allows exclusion or limitation which allow researchers to identify articles published by a single author or a single country. Based on this, we divided articles into two types: (1) single country publications (SCP) in which all authors have the same country affiliation and such publications represent an intra-country collaboration, and (2) multiple country publications (MCP) in which authors have different country affiliation and such publications represent inter-country collaboration.

In bibliometric studies, not all data can be presented. In most bibliometric studies, active or most productive countries, authors, institutions/organizations, and journals are usually presented. In this study, with large number of retrieved documents, only countries, authors, institutions, and journals with a minimum productivity of 100 documents were presented and ranked. The cutoff point of 100 publications have been previously used in other bibliometric studies [34]. For analysis pertaining to each infectious disease, only the top 10 productive countries were presented.

An important preventive aspect of most serious infectious diseases is the development of vaccines for prevention of spread. In this study, publications pertaining to vaccine development against any one of the top eight emerging pathogens were sought and presented. The search query used to search for vaccine development was the same search query used to retrieve publications on the top eight pathogens plus the keyword “vaccin*” with an asterisk to retrieve words such as vaccine or vaccination. The complete search query for vaccine data was presented in Fig. 1.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS - 21) was used to create graphs pertaining to growth of publications for each disease. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (Q1 – Q3) were used for descriptive statistics. Finally, bibliometric studies do not involve human or animal subjects and therefore, no ethical approval by Institutional Review Board was required.

Results

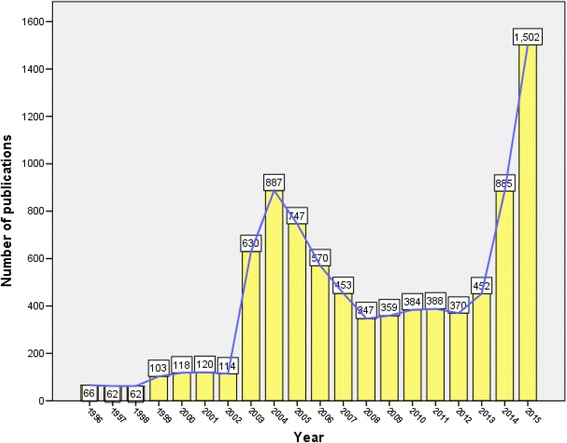

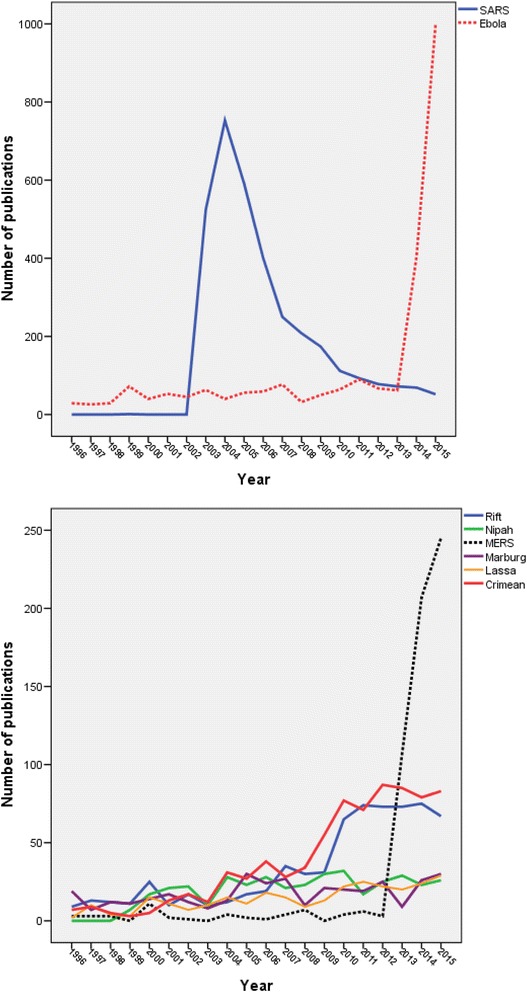

A total of 8619 journal articles were retrieved. The highest number of published articles was recorded in 2015 while the lowest number of published articles was recorded in 1996. The growth of publications showed a rising trend in 2003 and 2004 and then in 2014 and 2015. Figure 2 shows the annual growth of publications during the study period.

Fig. 2.

Annual growth of publications over the study period (1996–2015)

A total of 28 different languages were encountered in retrieved articles. English (n = 7,661; 88.9%) was the most common followed by Chinese (n = 387; 4.5%), French (206; 2.4%), and Russian (n = 131; 1.5%). The majority of retrieved articles were research articles (n = 6,587; 76.4%). Other types of retrieved documents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Types of retrieved documents

| Type of document | Frequency | % N = 8619 |

|---|---|---|

| Article | 6633 | 77.0 |

| Review | 984 | 11.4 |

| Letter | 304 | 3.5 |

| Note | 258 | 3.0 |

| Conference Paper | 192 | 2.2 |

| Editorial | 141 | 1.6 |

| Short Survey | 107 | 1.2 |

The majority of articles (n = 5,406; 62.7%) were published in peer reviewed journals in the subject area of “Medicine” while 3075 (35.7%) were published in peer reviewed journals in the subject area of “Immunology and Microbiology”. The subject areas with a minimum of 100 articles are shown in Table 2. Since some journals fit into more than one subject area, the total percentages in Table 2 exceeded 100%.

Table 2.

Subject areas of retrieved documents

| Subject area | Frequency | % N = 8619 a |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine | 5406 | 62.7 |

| Immunology and Microbiology | 3075 | 35.7 |

| Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology | 1681 | 19.5 |

| Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics | 533 | 6.2 |

| Agricultural and Biological Sciences | 407 | 4.7 |

| Veterinary | 283 | 3.3 |

| Multidisciplinary | 234 | 2.7 |

| Social Sciences | 179 | 2.1 |

| Chemistry | 170 | 2.0 |

| Environmental Science | 133 | 1.5 |

| Nursing | 123 | 1.4 |

aDue to overlap among subject areas, the total percentages exceeded 100%

Citation analysis

Retrieved documents received a total of 221,606 citations. The mean ± SD was 25.7 ± 65.4 citations per documents while the median (Q1 – Q3) was 9 (2–27). The h-index was 173. A total of 7291 (84.6%) articles were cited at least once while 1328 (15.4%) articles were not cited at all. A total of 408 (4.7%) publications received a minimum of 100 citations per article.

The article that received the highest number of citations was “A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome” [35] published in New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 2003. It received a total of 1979 citations. Table 3 shows the top 20 cited articles. Content analysis of top cited articles showed that 18 articles were about SARS, one about Nipah virus and one about Ebola virus. Five of top cited articles were published in NEJM, three in Lancet, six in Science, and three in Nature.

Table 3.

Top cited 20 articles on top eight emerging pathogens/infectious diseases

| Article | Year | Journal | Number of citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome [35] | 2003 | New England Journal of Medicine | 1979 |

| Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome [93] | 2003 | New England Journal of Medicine | 1810 |

| Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome [94] | 2003 | Lancet | 1535 |

| Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome [95] | 2003 | Science | 1479 |

| The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus [96] | 2003 | Science | 1295 |

| A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong [97] | 2003 | New England Journal of Medicine | 1135 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus [98] | 2003 | Nature | 943 |

| Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: A prospective study [99] | 2003 | Lancet | 916 |

| Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China [99] | 2003 | Science | 895 |

| Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada [100] | 2003 | New England Journal of Medicine | 827 |

| Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses [101] | 2005 | Science | 720 |

| A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong [102] | 2003 | New England Journal of Medicine | 677 |

| Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage [103] | 2003 | Journal of Molecular Biology | 638 |

| Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus [104] | 2005 | Nature | 606 |

| Nipah virus: A recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus [105] | 2000 | Science | 605 |

| Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 144 Patients with SARS in the Greater Toronto Area [106] | 2003 | Journal of the American Medical Association | 603 |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats [107] | 2005 | PNASa | 568 |

| Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus [108] | 2003 | Nature | 554 |

| Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome [109] | 2003 | Science | 535 |

| Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong [110] | 2003 | Lancet | 515 |

a PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Country analysis

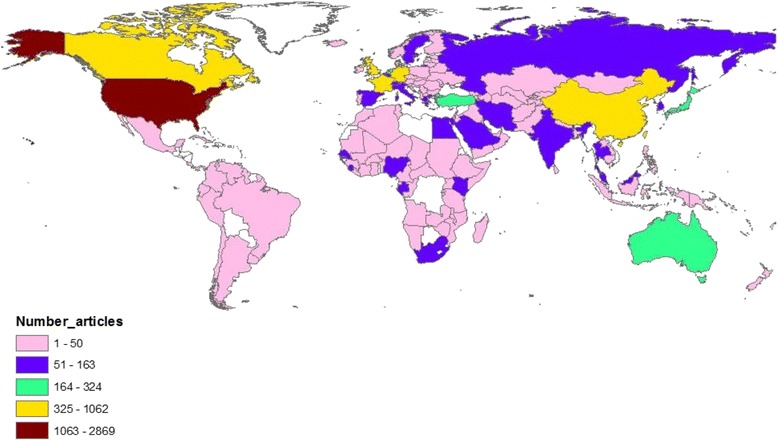

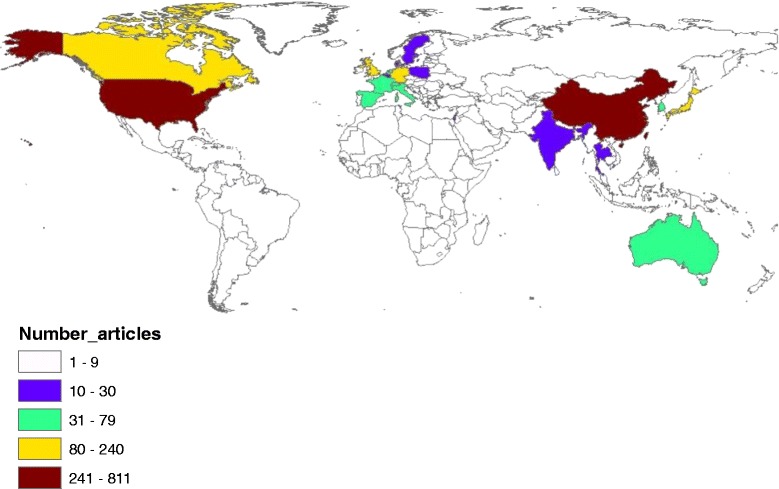

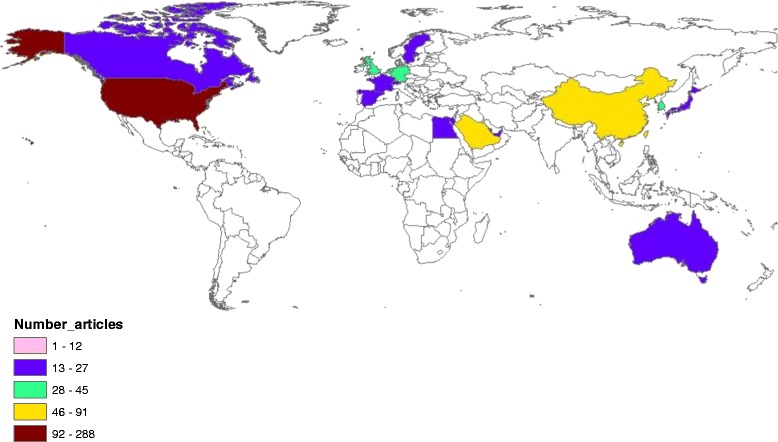

Researchers from 154 different countries participated in publishing retrieved articles. Table 4 shows a list of countries with a minimum contribution of 100 articles. The list included 23 different countries in North America, Middle East, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa. The total number of articles produced by the list of active countries was 6892 (80.0%). The United States of America (USA) ranked first in productivity with a total of 2852 (33.1%) followed by China (n = 1,057; 12.3%), Hong Kong (n = 548; 6.4%), and Germany (n = 608; 7.1%). Geographical distribution of worldwide publications on the top eight emerging pathogens was mapped using ArcGIS 10.1 with darker colors indicative of higher productivity (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

List of countries with a minimum contribution of 100 documents

| Country | Frequencya | % N = 8619 | SCP | % | MCP | % | TC | C/A | h-index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 2852 | 33.1 | 1499 | 52.6 | 1353 | 47.4 | 111552 | 39.1 | 145 |

| China | 1057 | 12.3 | 604 | 57.1 | 453 | 42.9 | 23153 | 21.9 | 67 |

| Germany | 608 | 7.1 | 203 | 33.4 | 405 | 66.6 | 28217 | 46.4 | 77 |

| Hong Kong | 548 | 6.4 | 326 | 59.5 | 222 | 40.5 | 26917 | 49.1 | 71 |

| Canada | 527 | 6.1 | 202 | 38.3 | 325 | 61.7 | 21809 | 41.4 | 75 |

| France | 521 | 6.0 | 170 | 32.6 | 351 | 67.4 | 18658 | 35.8 | 68 |

| UK | 470 | 5.5 | 132 | 28.1 | 338 | 71.9 | 14704 | 31.3 | 60 |

| Japan | 324 | 3.8 | 121 | 37.3 | 203 | 62.7 | 8309 | 25.6 | 48 |

| Turkey | 306 | 3.6 | 269 | 87.9 | 37 | 12.1 | 4375 | 14.3 | 30 |

| Taiwan | 285 | 3.3 | 228 | 80.0 | 57 | 20.0 | 7161 | 25.1 | 39 |

| Singapore | 255 | 3.0 | 142 | 55.7 | 113 | 44.3 | 9270 | 36.4 | 43 |

| Netherlands | 209 | 2.4 | 63 | 30.1 | 146 | 69.9 | 12989 | 62.1 | 50 |

| Australia | 195 | 2.3 | 43 | 22.1 | 152 | 77.9 | 6262 | 32.1 | 43 |

| South Africa | 160 | 1.9 | 47 | 29.4 | 113 | 70.6 | 6219 | 38.9 | 41 |

| Switzerland | 160 | 1.9 | 21 | 13.1 | 139 | 86.9 | 8659 | 54.1 | 44 |

| Spain | 150 | 1.7 | 61 | 40.7 | 89 | 59.3 | 3883 | 25.9 | 33 |

| Saudi Arabia | 142 | 1.6 | 51 | 35.9 | 91 | 64.1 | 4733 | 33.3 | 38 |

| Italy | 140 | 1.6 | 54 | 38.6 | 86 | 61.4 | 2930 | 20.9 | 29 |

| India | 123 | 1.4 | 74 | 60.2 | 49 | 39.8 | 1207 | 9.8 | 18 |

| Belgium | 109 | 1.3 | 18 | 16.5 | 91 | 83.5 | 4054 | 37.2 | 34 |

| Sweden | 104 | 1.2 | 33 | 31.7 | 71 | 68.3 | 2498 | 24.0 | 31 |

| Iran | 102 | 1.2 | 84 | 82.4 | 18 | 17.6 | 1264 | 12.4 | 19 |

| Malaysia | 100 | 1.2 | 58 | 58.0 | 42 | 42.0 | 4395 | 44.0 | 30 |

TC total citations, C/A citation per article, h-index Hirsch index, USA United States of America, UK United Kingdom, SCP single country publications, MCP multiple country publications

aWhen productivity of each country was calculated alone the total number exceeds the number of retrieved articles. However, when productivity of all countries was dealt with collectively, the total number will be lesser than that presented in the table. The collaboration between countries created some percentage of overlap and therefore certain number of similar countries were counted twice for collaborating countries

Fig. 3.

Geographical distribution of publications on the eight emerging pathogens. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.1 program. Regions with no colors in the map have no available data

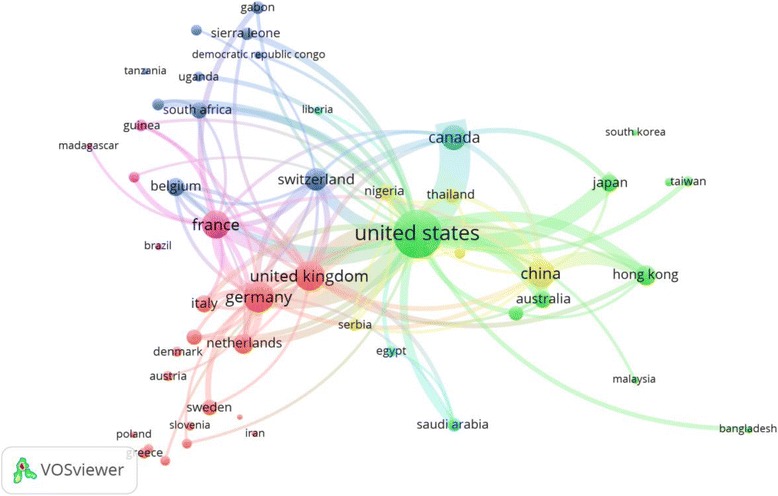

International collaboration ranged from 12.1 to 86.9%. Turkey had the lowest percentage (12.1%) of articles with international authors while Switzerland had the highest percentage (86.9%) of articles with international authors. Only two countries (Turkey and Iran) had less than 20% international collaboration. There was a significant correlation (Pearson correlation r = 0.52; p = 0.01) between percentage of international collaboration and number of citation per article but not with h-index. Visualization of international collaboration was created using VOSviewer technique. In the network visualization map, the strength of collaboration between countries is expressed by the thickness of the line between any two countries. Figure 4 shows inter-country collaboration between various developed and developing countries. The thickness of the connecting lines represents the extent of collaboration between any two countries.

Fig. 4.

Network visualization of inter-country collaborations among countries with minimum of 20 publications on emerging pathogens. Links represent the strength of collaboration

Institutions/organizations

Sixteen intuitions/organizations made a contribution of a minimum of 100 publications (Table 5). The total number of documents published by these active institutions was 3083 (35.8%). Eight active intuitions are in northern America (USA and Canada), three are in Hong Kong/China, two in Germany, one in France, one in Japan, and one is an international organization (WHO). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had the highest productivity of 344 (5.5%) articles followed by the University of Hong Kong with 305 (4.5%) documents. World Health Organization ranked 12th with 135 (1.6%) documents. However, publications by WHO had the highest citations per article (70.3) followed by those published by University of Hong Kong (60.4) and CDC (60.2). The CDC had the highest (87) h-index followed by U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (75) and The University of Hong Kong (63).

Table 5.

List of institutions/organizations with a minimum contribution of 100 documents

| Institution/Organization | Frequency | % N = 8619 | TC | C/A | h-index | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | 422 | 4.9 | 25410 | 60.2 | 87 | USA |

| The University of Hong Kong | 305 | 3.5 | 18425 | 60.4 | 63 | Hong Kong |

| U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases | 297 | 3.4 | 17027 | 57.3 | 75 | USA |

| National Institutes of Health, Bethesda | 209 | 2.4 | 7072 | 33.8 | 44 | USA |

| UT Medical Branch at Galveston | 208 | 2.4 | 6937 | 33.4 | 44 | USA |

| National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | 200 | 2.3 | 10371 | 51.9 | 56 | USA |

| Universitat Marburg | 182 | 2.1 | 10159 | 55.8 | 52 | Germany |

| Institut Pasteur, Paris | 175 | 2.0 | 8639 | 49.4 | 44 | France |

| University of Manitoba | 165 | 1.9 | 7289 | 44.2 | 51 | Canada |

| National Microbiology Laboratory | 163 | 1.9 | 7250 | 44.5 | 48 | Canada |

| Prince of Wales Hospital Hong Kong | 141 | 1.6 | 6600 | 46.8 | 40 | Hong Kong |

| Organisation Mondiale de la Sante | 135 | 1.6 | 9496 | 70.3 | 44 | WHO |

| National Institute of Infectious Diseases | 125 | 1.5 | 2356 | 18.8 | 28 | Japan |

| Chinese University of Hong Kong | 114 | 1.3 | 4601 | 40.4 | 33 | Hong Kong |

| Bernhard Nocht Institut fur Tropenmedizin Hamburg | 108 | 1.3 | 7241 | 67.0 | 36 | Germany |

| University of Toronto | 100 | 1.2 | 5071 | 50.7 | 32 | Canada |

TC total citations, C/A citation per article, h-index Hirsch index, USA United States of America, WHO World Health Organization

Journals and authors

Five journals made a contribution of at least 100 articles to studied diseases. Top leading journal was Journal of Virology with 572 (6.6%) articles. The journal is published by the American Society of Microbiology and has an IF of 4.6. The second ranking journal was Emerging Infectious Diseases with 295 (3.4%) publications; published by the CDC and has and IF of 6.99. The third ranking journal was Journal of Infectious Diseases with 244 (2.8%) articles; published on behalf of Infectious Diseases Society of America and has an IF of 6.3. The fourth ranking journal was Virology journal with 194 (2.3%) articles; published by Elsevier and has an impact factor of 3.2. The fifth ranking journal was Plos One with 146 (1.7%) articles; published by Public Library of Science, and has an IF of 3.1.

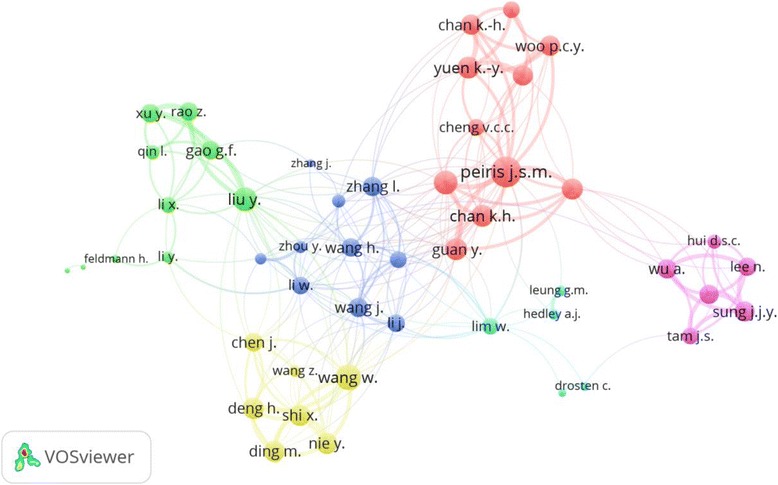

Feldmann, Heinz R. at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Laboratory of Virology, was the most productive researcher with 197 (2.3%) articles. Rollin, Pierre Etienne at CDC, Atlanta, USA ranked second with 123 (1.4%) articles. Ksiazek, Thomas G. at Galveston National Laboratory, Galveston, USA ranked third with 118 (1.4%) articles. Nichol, Stuart T., at the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, USA, ranked fourth with 112 (1.3%) articles. Geisbert, Thomas Thomas, at UT Medical Branch at Galveston, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Galveston, USA ranked fifth with 103 (1.2%) articles. Figure 5 is a visualization map of author collaboration. The map had 6 clusters of names of authors. Each cluster represents a research group working on particular pathogen(s).

Fig. 5.

Network visualization map of author collaboration. Cluster of authors having similar cluster color most probably represents a closely related research group

Publication activity on each disease

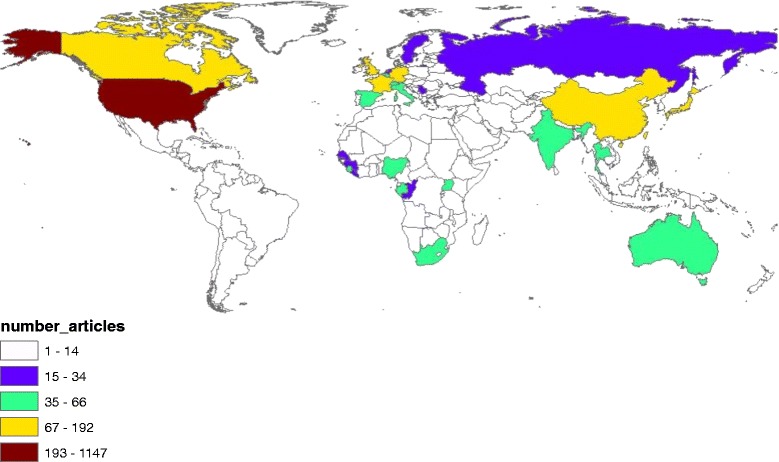

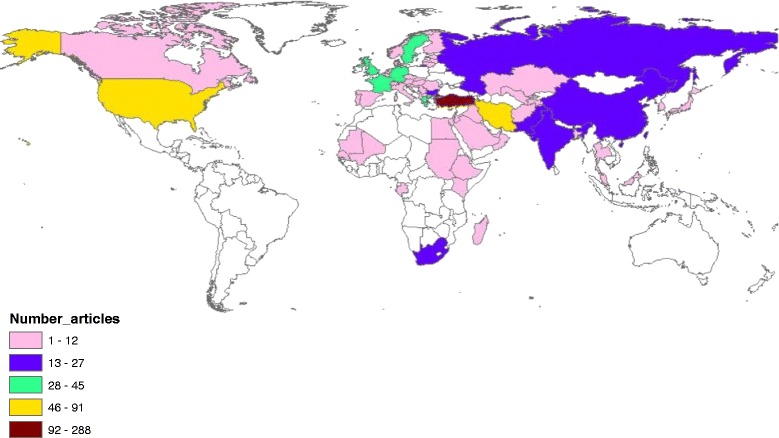

Table 6 shows the number of retrieved articles for each type of disease. Due to the presence of articles that might have discussed more than one pathogen/infectious disease at the same time, the total percentages exceeded 100%. Publications on SARS (3379; 39.2%) ranked first in quantity followed by those on Ebola (2355; 27.3%) and Crimean-Congo (766; 8.9%). Geographical distribution of research publications on SARS, Ebola, Crimean – Congo, and MERS were mapped and presented in Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9. The annual growth of publications showed that publications on SARS exhibited a sharp peak in 2003, publications on Ebola exhibited a sharp peak in 2014, and publications on MERS exhibited a clear rise starting from 2012 (Fig. 10a and b).

Table 6.

Number of publications on each disease

| Rank | Disease | Frequency | % | h-index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | SARS | 3379 | 39.2 | 115 |

| 2nd | Ebola | 2355 | 27.3 | 120 |

| 3rd | Crimean – Congo | 766 | 8.9 | 54 |

| 4th | Rift valley fever | 678 | 7.9 | 61 |

| 5th | MERS | 613 | 7.1 | 51 |

| 6th | Nipah | 382 | 4.4 | 63 |

| 7th | Marburg | 354 | 4.1 | 55 |

| 8th | Lassa | 285 | 3.3 | 47 |

SARS Severe acute respiratory syndrome, MERS Middle East respiratory syndrome, h-index Hirsch index

Due to overlap, total percentage exceeded 100%

Fig. 6.

Geographical distribution of publications on SARS. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.1 program. Regions with no colors in the map have no available data

Fig. 7.

Geographical distribution of publications on Ebola. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.1 program. Regions with no colors in the map have no available data

Fig. 8.

Geographical distribution of publications on Ebola. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.1 program. Regions with no colors in the map have no available data

Fig. 9.

Geographical distribution of publications on MERS. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.1 program. Regions with no colors in the map have no available data

Fig. 10.

a Growth of publication on Ebola and SARS (1996–2015). b Growth of publications on “Crimean – Congo, Marburg, Lassa fever, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Nipah, and Rift Valley fever” (1996–2015)

Country analysis of publications on each disease is shown in Table 7. The USA ranked first in productivity in research pertaining to Mraburg, Ebola, Rift valley fever, Nipah, MERS, and Lassa. However, China ranked first in SARS while Turkey ranked first in Crimean-Congo fever. For SARS virus, half of the top 10 list were Asian countries while for Nipah virus, four Asian countries appeared in the top 10 list; Malaysia, Bangladesh, Japan, and Singapore. The USA, the UK, and Germany appeared in the top 10 productive list for all diseases. China and/or Hong Kong were in the top 10 productive list for Ebola, MERS, and SARS. Analysis of h-index of publications pertaining to each disease showed that publications on Ebola (120) had the highest h-index followed by SARS (115), Nipah (63) and rift valley fever (61).

Table 7.

Top 10 productive countries for each pathogen/infectious disease

| SARS | Frequency | % N = 3379 | Crimean-Congo | Frequency | % N = 766 | Marburg | Frequency | % N = 354 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 811 | 24.0 | Turkey | 288 | 37.6 | USA | 154 | 43.5 |

| USA | 786 | 23.3 | Iran | 91 | 11.9 | Germany | 65 | 18.4 |

| Hong Kong | 499 | 14.8 | USA | 91 | 11.9 | Canada | 29 | 8.2 |

| Taiwan | 276 | 8.2 | UK | 45 | 5.9 | Japan | 23 | 6.5 |

| Canada | 240 | 7.1 | Germany | 41 | 5.4 | France | 20 | 5.6 |

| Singapore | 211 | 6.2 | Greece | 41 | 5.4 | UK | 18 | 5.1 |

| Germany | 167 | 4.9 | France | 36 | 4.7 | Belgium | 13 | 3.7 |

| UK | 131 | 3.9 | Sweden | 35 | 4.6 | Switzerland | 13 | 3.7 |

| Japan | 127 | 3.8 | Russian Fed. | 27 | 3.5 | South Africa | 12 | 3.4 |

| Netherlands | 79 | 2.3 | Bulgaria | 24 | 3.1 | Congo | 11 | 3.1 |

| Ebola | Frequency | % N = 2355 | Rift valley fever | Frequency | % N = 678 | MERS | Frequency | % N = 613 |

| USA | 1147 | 48.7 | USA | 263 | 38.8 | USA | 201 | 32.8 |

| Canada | 192 | 8.2 | France | 124 | 18.3 | Saudi Arabia | 96 | 15.7 |

| France | 192 | 8.2 | South Africa | 75 | 11.1 | China | 82 | 13.4 |

| Germany | 186 | 7.9 | Kenya | 68 | 10.0 | UK | 55 | 9.0 |

| UK | 160 | 6.8 | Senegal | 46 | 6.8 | Germany | 54 | 8.8 |

| China | 122 | 5.2 | UK | 41 | 6.0 | Hong Kong | 45 | 7.3 |

| Japan | 113 | 4.8 | Saudi Arabia | 31 | 4.6 | Netherlands | 44 | 7.2 |

| Switzerland | 66 | 2.8 | Egypt | 28 | 4.1 | South Korea | 37 | 6.0 |

| Nigeria | 58 | 2.5 | Germany | 28 | 4.1 | France | 27 | 4.4 |

| India | 56 | 2.4 | Netherlands | 27 | 4.0 | Japan | 23 | 3.8 |

| Nipah | Frequency | % N = 382 | Lassa | Frequency | % N = 285 | |||

| USA | 186 | 48.7 | USA | 123 | 43.2 | |||

| Malaysia | 88 | 23.0 | Germany | 74 | 26.0 | |||

| Australia | 66 | 17.3 | France | 34 | 11.9 | |||

| Bangladesh | 29 | 7.6 | Nigeria | 32 | 11.2 | |||

| France | 25 | 6.5 | Sierra Leone | 19 | 6.7 | |||

| Canada | 23 | 6.0 | Guinea | 17 | 6.0 | |||

| Japan | 19 | 5.0 | Canada | 15 | 5.3 | |||

| Germany | 17 | 4.5 | UK | 12 | 4.2 | |||

| Singapore | 16 | 4.2 | Netherlands | 10 | 3.5 | |||

| UK | 15 | 3.9 | Belgium | 9 | 3.2 | |||

| Japan | 9 | 3.2 | ||||||

SARS Severe acute respiratory syndrome, MERS Middle East respiratory

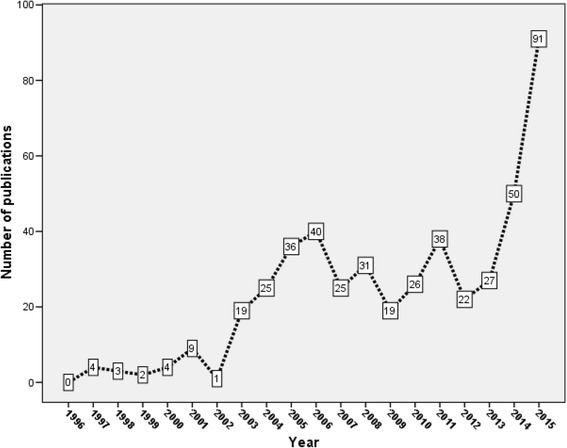

Publications on vaccine development

Four hundred seventy-two publications were related to vaccine development. Research activity on vaccine development showed similar trend to overall research activity on the top eight emerging disease (Fig. 11). As expected Vaccine journal (68, 14.4%) ranked first in productivity followed by Journal of Virology (40, 8.5%). The USA was the most productive country in this field with 254 (53.8%) followed distantly by China (70; 14.8%) and Canada (54; 11.4%). Professor Feldmann H. (36; 7.6%) was the most prolific author in this field. Top 20 cited articles on vaccines against studied pathogens/infectious diseases are shown in Table 8. Development of a vaccine against Ebola, SARS, Nipah, or Lassa was the main focus of vaccine – related studies. Ten articles in the top 20 list were about Ebola, five were about SARS, two were about Marburg, one was about Nipah, one about Lassa fever, and one article was about both Ebola and Marburg viruses.

Fig. 11.

Growth of publications on vaccine research on emerging pathogens (1996–2015)

Table 8.

Top 20 cited articles on vaccine – related publication on studied diseases

| Title | Year | Journal | Number of citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development of a preventive vaccine for Ebola virus infection in primates [111] | 2000 | Nature | 490 |

| Accelerated vaccination for Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever in non-human primates [112] | 2003 | Nature | 336 |

| Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses [113] | 2005 | Nature Medicine | 320 |

| A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice [114] | 2004 | Nature | 320 |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein expressed by attenuated vaccinia virus protectively immunizes mice [115] | 2004 | PNAS | 232 |

| Marburg virus vaccines based upon alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs and nonhuman primates [116] | 1998 | Virology | 199 |

| Effects of a SARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in monkeys [117] | 2003 | Lancet | 168 |

| Ebola virus: From discovery to vaccine [118] | 2003 | Nature Reviews Immunology | 168 |

| Evaluation in nonhuman primates of vaccines against Ebola virus [119] | 2002 | Emerging Infectious Diseases | 166 |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome vaccine development: Experiences of vaccination against avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus [120] | 2003 | Avian Pathology | 152 |

| Ebola virus-like particle-based vaccine protects nonhuman primates against lethal Ebola virus challenge [121] | 2007 | Journal of Infectious Diseases | 149 |

| Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine expressing Ebola surface glycoprotein: interim results from the Guinea ring vaccination cluster-randomised trial [122] | 2015 | The Lancet | 137 |

| DNA vaccines expressing either the GP or NP genes of Ebola virus protect mice from lethal challenge [123] | 1998 | Virology | 136 |

| A DNA vaccine for Ebola virus is safe and immunogenic in a phase I clinical trial [124] | 2006 | Clinical and Vaccine Immunology | 134 |

| Single-injection vaccine protects nonhuman primates against infection with Marburg virus and three species of Ebola virus [125] | 2009 | Journal of Virology | 127 |

| Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever [126] | 2005 | PLoS Medicine | 115 |

| Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces highly potent neutralizing antibodies: Implication for developing subunit vaccine [127] | 2004 | Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications | 115 |

| Correlates of protective immunity for Ebola vaccines: Implications for regulatory approval by the animal rule [128] | 2009 | Nature Reviews Microbiology | 105 |

| Nipah Virus: Vaccination and Passive Protection Studies in a Hamster Model [129] | 2004 | Journal of Virology | 105 |

| Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region [130] | 2005 | Journal of Virology | 101 |

PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Discussion

This study was carried out to assess worldwide research activity on emerging pathogens expected to cause serious fatal outbreaks in the near future. Several bibliometric studies were carried out and published on infectious diseases in general or on a specific disease such as Ebola [36], SARS [37, 38], and Nipah [39, 40]. However, no bibliometric study was carried out on research activity on a group of viruses suspected of potential outbreaks in the near future. These emerging pathogens need to be looked at as one unit since most of them have similar pathogenic and epidemiologic characteristics.

Our study showed that research activity on emerging pathogens showed an uprising peak in 2003 due to the outbreak of SARS at that time, particularly in Asian countries. Another uprising peak of publications was seen in 2014 due to outbreak of Ebola virus and to a lesser extent the outbreak of MERS-CoV. Between the two peaks of SARS and Ebola, there was a high plateau of research activity that is most probably due to the rise in the number of publications about the remaining five diseases.

International collaboration in research on emerging diseases was high possibly due to spread of these viral infectious outbreaks across borders. Furthermore, the relatively high h-index of 173 indicates that research on these diseases is receiving a high number of citations suggestive of importance and large number of readers. A study concluded that the h-index can be used to estimate the potential impact of a pathogen and to rank individual pathogens or types of pathogens [41]. In our study, Ebola and SARS had the highest h-indices which necessitate prioritizing these two pathogens in planning for the future preventive policies. The finding that Professor Feldmann, R. was the most prolific researcher was confirmed by other bibliometric studies [34].

Infectious diseases like acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), malaria, and tuberculosis are major infectious diseases affecting millions of people and draining billions of US dollars of research funds [42, 43]. Research activity on malaria, tuberculosis, and AIDS have made some success in controlling the spread of such diseases and in developing potent and effective therapies. For example, the discovery of the effective drug artemisinin has greatly changed the therapeutic approach of malaria and enhanced control and eradication of malaria [44–46]. Actually, the Chinese scientist Tu Youyou, who discovered the drug artemisinin, was awarded Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015 [47, 48]. In case of the top eight emerging pathogens which are expected to cause serious outbreaks in the near future, no effective therapy is available so far and no preventive measures are being developed to face a sudden worldwide outbreak of these infectious diseases. Calls for strengthening preparedness for Crimean-Congo [49] and MERS-coronavirus [50–52] have been published. The WHO stated that research remains the cornerstone for reversing trends of serious outbreaks of certain viral diseases and that research will improve methods for surveillance, prevention, and control. Unfortunately, the increased funding for AIDS created a shortage of funding for other infectious diseases [53]. A study that compared research output and citations among three infectious diseases indicated that funding has a positive influence on research output and citations for a particular disease [54].

In most bibliometric studies, the USA, the UK, Germany, and other European countries appeared in the most active list of publications. However, in this study, additional countries in Asia and Africa, and Middle east did appear in the top active list for each disease emphasizing the global threat of such infectious diseases. A bibliometric analysis on infectious diseases reported that USA ranked as top productive country but China is increasing its place among the top five countries [55]. Actually, many countries start to focus their research efforts on infectious diseases as a national health burden [56]. The participation of Asian, African, and Middle eastern countries in research activity pertaining to top eight emerging infectious diseases was clear and prominent. Outbreaks of emerging viral infectious diseases have been commonly reported from many countries in Africa, Asia, and Africa [52, 57–62]. For example, MERS-CoV and Crimean-Congo fever have been reported in more than 20 countries, mostly in Asia, Africa, and Middle East [63–77]. The outbreaks of SARS in Hong Kong and China had a great economic and public health impact [78–80]. Many of these infectious diseases were initially reported in Africa, such as Ebola, Lassa fever, and Rift valley fever [81–86]. The Marburg virus was initially reported in Germany and spread to other neighboring countries and that is why China and Hong Kong did not show in the top productive countries on Marburg disease.

Our study has few limitations that need to be stated. Scopus is a large and comprehensive database but not all journals are indexed in Scopus and therefore, some articles about the studied diseases published in un-indexed journals might be missed. Furthermore, the keywords used might not be 100% accurate although the validity of the search query was tested by manual review of 10% of retrieved articles, false positive and false negative results remain a possibility. The ranking of countries and institutions based on citations did not take into account self-citations which affects the validity of results. These limitations and others are found in most bibliometric studies [71, 87–91]. This study focused only on the top eight emerging infectious diseases expected to cause severe outbreaks in the near future. However, the other three serious infectious diseases which in include Zaika were not included in the analysis. Finally, we should always bear in mind that no database is perfect and even might have some bias by over-representing journals with English language. Therefore, bibliometric results should always be considered with caution [92].

Conclusions

The number of publications on diseases expected to cause severe outbreaks in the near future showed two clear peaks in the past two decades; one for SARS and one for Ebola. The clear increase in number of publication on the studied diseases during relatively short period of time is an indication of how science and health information flows rapidly across borders to create similar concerns among different countries. Bibliometric methods can be used to prioritize efforts and direct research funds to help control emerging diseases [41]. Although the USA is leading the research on these diseases, the share of Asian, African, and Middle Eastern countries was apparent. International collaboration in research on these diseases was relatively high for most countries. Search for an effective vaccine was clearly strong for Ebola and SARS.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge professors Saed Zyoud and Adham Abu-Taha for their technical and professional editing.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

all data present in this article can be retrieved from Scopus using keywords listed in the methodology.

Authors’ contributions

This is a single author publication. The author was in charge of data collection, writing, analysis, submission and revision.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MERS

Middle East respiratory Syndrome

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- WHO

World Health Organization

References

- 1.Blueprint for R&D preparedness and response to public health emergencies due to highly infectious pathogens [http://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/WHO-list-of-top-emerging-diseases/en/].

- 2.Akinci E, Bodur H, Sunbul M, Leblebicioglu H. Prognostic factors, pathophysiology and novel biomarkers in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antivir Res. 2016;132:233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brackney DE, Armstrong PM. Transmission and evolution of tick-borne viruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;21:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shayan S, Bokaean M, Shahrivar MR, Chinikar S. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Lab Med. 2015;46(3):180–9. doi: 10.1309/LMN1P2FRZ7BKZSCO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zivcec M, Scholte FE, Spiropoulou CF, Spengler JR, Bergeron E. Molecular insights into Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Viruses. 2016;8(4):106. doi: 10.3390/v8040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaner J, Schaack S. Understanding Ebola: the 2014 epidemic. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0194-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leligdowicz A, Fischer WA, 2nd, Uyeki TM, Fletcher TE, Adhikari NK, Portella G, Lamontagne F, Clement C, Jacob ST, Rubinson L, et al. Ebola virus disease and critical illness. Critical Care (London, England) 2016;20(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivera A, Messaoudi I. Molecular mechanisms of Ebola pathogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(5):889–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Brainard J, Pond K, Hooper L, Edmunds K, Hunter P. Presence and persistence of Ebola or Marburg virus in patients and survivors: a rapid systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaze ER, Roy MJ, Dalrymple LW, Lanning LL. A comparison of the pathogenesis of Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primates and evaluation of the suitability of these animal models for predicting clinical efficacy under the ‘Animal Rule’. Comp Med. 2015;65(3):241–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messaoudi I, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. Filovirus pathogenesis and immune evasion: insights from Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(11):663–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pigott DM, Golding N, Mylne A, Huang Z, Weiss DJ, Brady OJ, Kraemer MU, Hay SI. Mapping the zoonotic niche of Marburg virus disease in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109(6):366–78. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodhain F. [Bats and viruses: complex relationships] Bull Soc Pathol Exot (1990) 2015;108(4):272–89. doi: 10.1007/s13149-015-0448-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Bahnasawy MM, Megahed LA, Abdalla Saleh HA, Morsy TA. Lassa fever or lassa hemorrhagic fever risk to humans from rodent-borne zoonoses. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2015;45(1):61–70. doi: 10.12816/0010850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mylne AQ, Pigott DM, Longbottom J, Shearer F, Duda KA, Messina JP, Weiss DJ, Moyes CL, Golding N, Hay SI. Mapping the zoonotic niche of Lassa fever in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109(8):483–92. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik M, Elkholy AA, Khan W, Hassounah S, Abubakar A, Minh NT, Mala P. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: current knowledge and future considerations. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;22(7):537–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mo Y, Fisher D. A review of treatment modalities for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(12):3340–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mohd HA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virol J. 2016;13:87. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hazmi A. Challenges presented by MERS corona virus, and SARS corona virus to global health. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2016;23(4):507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijay R, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;16:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angeletti S, Lo Presti A, Cella E, Ciccozzi M. Molecular epidemiology and phylogeny of nipah virus infection: a mini review. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(7):630–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Wit E, Munster VJ. Animal models of disease shed light on Nipah virus pathogenesis and transmission. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):196–205. doi: 10.1002/path.4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escaffre O, Borisevich V, Rockx B. Pathogenesis of Hendra and Nipah virus infection in humans. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(4):308–11. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han HJ, Wen HL, Zhou CM, Chen FF, Luo LM, Liu JW, Yu XJ. Bats as reservoirs of severe emerging infectious diseases. Virus Res. 2015;205:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baba M, Masiga DK, Sang R, Villinger J. Has Rift Valley fever virus evolved with increasing severity in human populations in East Africa? Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e58. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bird BH, McElroy AK. Rift valley fever virus: unanswered questions. Antivir Res. 2016;132:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenzo G, Lopez-Gil E, Warimwe GM, Brun A. Understanding Rift Valley fever: contributions of animal models to disease characterization and control. Mol Immunol. 2015;66(1):78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansfield KL, Banyard AC, McElhinney L, Johnson N, Horton DL, Hernandez-Triana LM, Fooks AR. Rift valley fever virus: a review of diagnosis and vaccination, and implications for emergence in Europe. Vaccine. 2015;33(42):5520–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiley CA, Bhardwaj N, Ross TM, Bissel SJ. Emerging infections of CNS: avian influenza a virus, rift valley fever virus and human parechovirus. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland) 2015;25(5):634–50. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi-Omoe H, Omoe K. Worldwide trends in infectious disease research revealed by a new bibliometric method. INTECH Open Access Publisher; 2012.

- 31.Unkel S, Farrington C, Garthwaite PH, Robertson C, Andrews N. Statistical methods for the prospective detection of infectious disease outbreaks: a review. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc. 2012;175(1):49–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2011.00714.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22(2):338–42. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg K, Kumar S. Bibliometrics of global Ebola Virus Disease research as seen through Science Citation Index Expanded during 1987–2015. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1953–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramakrishnan J, Sankar GR. Bibliometric Analysis of Literature on Ebola (1995–2014) Indian J Libr Inf Sci. 2015;9(2):133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiu W-T, Huang J-S, Ho Y-S. Bibliometric analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related research in the beginning stage. Scientometrics. 2004;61(1):69–77. doi: 10.1023/B:SCIE.0000037363.49623.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.GUAN J, LI Z-f, CHEN W-k, ZHONG W-j. Bibliometric analysis of SARS literature [J] Chin J Med Libr. 2004;2:037. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safahieh H, Sanni S, Zainab A: International Contribution to Nipah Virus Research 1999–2010. arXiv preprint arXiv:13015384 2013.

- 40.Sanni S, Safahieh H, Zainab A, Abrizah A, Raj R. Evaluating the growth pattern and relative performance in Nipah virus research from 1999 to 2010. Malaysi J Libr Inf Sci. 2013;18(2):14–24. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox R, McIntyre K, Sanchez J, Setzkorn C, Baylis M, Revie C: Comparison of the h‐Index Scores Among Pathogens Identified as Emerging Hazards in North America. Transboundary and emerging diseases 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Allen T, Parker M. Will increased funding for neglected tropical diseases really make poverty history? Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1097–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eurosurveillance editorial team. The European Union provides funding to strengthen the protection against zoonoses and animal diseases. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(46). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Hempelmann E, Tesarowicz I, Oleksyn BJ. From onions to artemisinin. Brief history of malaria chemotherapy. Pharm Unserer Zeit. 2009;38(6):500–7. doi: 10.1002/pauz.200900336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White NJ. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(7):1413–22. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown G. Artemisinin and a new generation of antimalarial drugs. Educ Chem. 2006;43(4):97–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Callaway E, Cyranoski D. Anti-parasite drugs sweep Nobel prize in medicine 2015. Nature. 2015;526(7572):174–5. doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.18507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klayman DL. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): an antimalarial drug from China. Science. 1985;228(4703):1049–55. doi: 10.1126/science.3887571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maltezou H, Andonova L, Andraghetti R, Bouloy M, Ergonul O, Jongejan F, Kalvatchev N, Nichol S, Niedrig M, Platonov A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Europe: current situation calls for preparedness. EuroSurveill. 2010;15(10):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Abaidani IS, Al-Maani AS, Al-Kindi HS, Al-Jardani AK, Abdel-Hady DM, Zayed BE, Al-Harthy KS, Al-Shaqsi KH, Al-Abri SS. Overview of preparedness and response for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Oman. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:309–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Sousa R, Reusken C, Koopmans M. MERS coronavirus: data gaps for laboratory preparedness. J Clin Virol. 2014;59(1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng OW, Tan YJ. Understanding bat SARS-like coronaviruses for the preparation of future coronavirus outbreaks - Implications for coronavirus vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;13(1):186–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Fleischer T, Kevany S, Benatar SR. Will escalating spending on HIV treatment displace funding for treatment of other diseases? S Afr Med J. 2010;100(1):32–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Head MG, Fitchett JR, Derrick G, Wurie FB, Meldrum J, Kumari N, Beattie B, Counts CJ, Atun R. Comparing research investment to United Kingdom institutions and published outputs for tuberculosis, HIV and malaria: a systematic analysis across 1997–2013. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sipahi O, Sipahi H, Tasbakan M, Pullukcu H, Arda B, Yamazhan T, Ulusoy S. Bibliometric analysis of publications in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology areas: Which coutries led in 1996–2011 and 2011 periods? Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21:245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramos J, González-Alcaide G, Gutiérrez F. [Bibliometric analysis of the Spanish scientific production in Infectious Diseases and Microbiology] Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2016;34(3):166–76. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coker RJ, Hunter BM, Rudge JW, Liverani M, Hanvoravongchai P. Emerging infectious diseases in southeast Asia: regional challenges to control. Lancet. 2011;377(9765):599–609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen T, Leung RK-K, Liu R, Chen F, Zhang X, Zhao J, Chen S. Risk of imported Ebola virus disease in China. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12(6):650–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, Rieger T, Koivogui L, Magassouba NF, Soropogui B, Sow MS, Keïta S, De Clerck H. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(15):1418–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan M. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—no early end to the outbreak. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1183–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1409859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dixon MG, Schafer IJ. Ebola viral disease outbreak—West Africa, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):548–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Himeidan YE, Kweka EJ, Mahgoub MM, El Rayah el A, Ouma JO. Recent outbreaks of rift valley Fever in East Africa and the middle East. Front Public Health. 2014;2:169. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhatia PK, Sethi P, Gupta N, Biyani G. Middle East respiratory syndrome: a new global threat. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60(2):85–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.176286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hunter JC, Nguyen D, Aden B, Al Bandar Z, Al Dhaheri W, Abu Elkheir K, Khudair A, Al Mulla M, El Saleh F, Imambaccus H, et al. Transmission of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in healthcare settings, Abu Dhabi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(4):647–56. doi: 10.3201/eid2204.151615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim KM, Ki M. Epidemiologic features of the first MERS outbreak in Korea: focus on Pyeongtaek St. Mary’s Hospital. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015041. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mishra B. Combating the spread of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Indian perspective. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34(2):135–6. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.176851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nah K, Otsuki S, Chowell G, Nishiura H. Predicting the international spread of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:356. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1675-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park SH. Outbreaks of middle east respiratory syndrome in Two hospitals initiated by a single patient in daejeon, south Korea. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;48(2):99–107. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2015.1087648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Poletto C, Colizza V, Boelle PY. Quantifying spatiotemporal heterogeneity of MERS-CoV transmission in the Middle East region: a combined modelling approach. Epidemics. 2016;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zumla A, Alagaili AN, Cotten M, Azhar EI. Infectious diseases epidemic threats and mass gatherings: refocusing global attention on the continuing spread of the Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) BMC Med. 2016;14(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sweileh WM, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF, Zyoud SH. Bibliometric profile of the global scientific research on autism spectrum disorders. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1480. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leblebicioglu H, Sunbul M, Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Bodur H, Ozkul A, Gucukoglu A, Chinikar S, Hasan Z. Consensus report: preventive measures for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever during Eid-al-adha festival. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;38:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mohamed Al Dabal L, Rahimi Shahmirzadi MR, Baderldin S, Abro A, Zaki A, Dessi Z, Al Eassa E, Khan G, Shuri H, Alwan AM. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2010: case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(8):e38374. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.38374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pourhossein B, Irani AD, Mostafavi E. Major infectious diseases affecting the Afghan immigrant population of Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015002. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saleem J, Usman M, Nadeem A, Sethi SA, Salman M. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: a first case from Abbottabad, Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(3):e121–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yadav PD, Gurav YK, Mistry M, Shete AM, Sarkale P, Deoshatwar AR, Unadkat VB, Kokate P, Patil DY, Raval DK, et al. Emergence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Amreli District of Gujarat State, India, June to July 2013. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;18:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yilmaz R, Ozcetin M, Erkorkmaz U, Ozer S, Ekici F. Public knowledge and attitude toward Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever in Tokat Turkey. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2009;3(2):12–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lau AL, Chi I, Cummins RA, Lee TM, Chou K-L, Chung LW. The SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) pandemic in Hong Kong: effects on the subjective wellbeing of elderly and younger people. Aging Mental Health. 2008;12(6):746–60. doi: 10.1080/13607860802380607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee K. How the Hong Kong government lost the public trust in SARS: insights for government communication in a health crisis. Public Relat Rev. 2009;35(1):74–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Keogh-Brown MR, Smith RD. The economic impact of SARS: how does the reality match the predictions? Health Policy. 2008;88(1):110–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohuabunwo C, Ameh C, Oduyebo O, Ahumibe A, Mutiu B, Olayinka A, Gbadamosi W, Garcia E, Nanclares C, Famiyesin W et al. Clinical profile and containment of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in two large West African cities, Nigeria, July-September 2014. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;53:23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Rosello A, Mossoko M, Flasche S, Van Hoek AJ, Mbala P, Camacho A, Funk S, Kucharski A, Ilunga BK, Edmunds WJ et al. Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1976–2014. eLife 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Safari S, Baratloo A, Rouhipour A, Ghelichkhani P, Yousefifard M. Ebola hemorrhagic fever as a public health emergency of international concern; a review article. Emergency (Tehran, Iran) 2015;3(1):3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Rift Valley fever outbreak--Kenya, November 2006-January. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007. 2007;56(4):73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faye O, Diallo M, Diop D, Bezeid OE, Ba H, Niang M, Dia I, Mohamed SA, Ndiaye K, Diallo D, et al. Rift Valley fever outbreak with East-Central African virus lineage in Mauritania, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(7):1016–23. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Munyua P, Murithi RM, Wainwright S, Githinji J, Hightower A, Mutonga D, Macharia J, Ithondeka PM, Musaa J, Breiman RF, et al. Rift Valley fever outbreak in livestock in Kenya, 2006–2007. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2 Suppl):58–64. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of literature on female genital mutilation: (1930–2015) Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sweileh WM, Shraim NY, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF, AbuTaha AS, Zyoud SH. Bibliometric analysis of global scientific research on carbapenem resistance (1986–2015) Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016;15(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sweileh WM, Shraim NY, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF, Rahhal B, Khayyat RA, Zyoud SH. Assessing worldwide research activity on probiotics in pediatrics using Scopus database: 1994–2014. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:25. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sweileh WM, Shraim NY, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW. Worldwide research productivity on tramadol: a bibliometric analysis. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1108. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2801-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF, Shraim NY. Drinking and recreational water-related diseases: a bibliometric analysis (1980–2015) Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s40557-016-0128-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics. 2016;106(1):213–28. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, Van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RAM, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peiris JSM, Lai ST, Poon LLM, Guan Y, Yam LYC, Lim W, Nicholls J, Yee WKS, Yan WW, Cheung MT, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9366):1319–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, Nix WA, Campagnoli R, Icenogle JP, Peñaranda S, Bankamp B, Maher K, Chen MH, et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5624):1394–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marra MA, Jones SJM, Astell CR, Holt RA, Brooks-Wilson A, Butterfield YSN, Khattra J, Asano JK, Barber SA, Chan SY, et al. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300(5624):1399–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, Ahuja A, Yung MY, Leung CB, To KF, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1986–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasllieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greeneugh TC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, Liu XL, Zhuang ZX, Cheung CL, Luo SW, Li PH, Zhang LJ, Guan YJ, et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, Finkelstein S, Rose D, Green K, Tellier R, Draker R, Adachi D, Ayers M, et al. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, Wang H, Crameri G, Hu Z, Zhang H, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310(5748):676–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, Lam WK, Seto WH, Yam LY, Cheung TM, et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1977–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Snijder EJ, Bredenbeek PJ, Dobbe JC, Thiel V, Ziebuhr J, Poon LLM, Guan Y, Rozanov M, Spaan WJM, Gorbalenya AE. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J Mol Biol. 2003;331(5):991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska JT, Gonzalez JP, Swanepoel R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438(7068):575–6. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chua KB. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science. 2000;288(5470):1432–5. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Booth CM, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, Rachlis AR, Rose DB, Dwosh HA, Walmsley SL, Mazzulli T, Avendano M, Derkach P, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289(21):2801–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lau SKP, Woo PCY, Li KSM, Huang Y, Tsoi HW, Wong BHL, Wong SSY, Leung SY, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):14040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fouchier RAM, Kuiken T, Schutten M, Van Amerongen G, Van Doornum GJJ, Van Den Hoogen BG, Peiris M, Lim W, Stöhr K, Osterhaus ADME. Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423(6937):240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, Robins JM, Ma S, James L, Gopalakrishna G, Chew SK, Tan CC, Samore MH, et al. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300(5627):1966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Leung GM, Hedley AJ, Fraser C, Riley S, Abu-Raddad LJ, Ho LM, Thach TQ, Chau P, et al. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1761–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sullivan NJ, Sanchez A, Rollin PE, Yang ZY, Nabel GJ. Development of a preventive vaccine for Ebola virus infection in primates. Nature. 2000;408(6812):605–9. doi: 10.1038/35046108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sullivan NJ, Geisbert TW, Gelsbert JB, Xu L, Yang ZY, Roederer M, Koup RA, Jahrling PB, Nabel GJ. Accelerated vaccination for Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever in non-human primates. Nature. 2003;424(6949):681–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jones SM, Feldmann H, Ströher U, Geisbert JB, Fernando L, Grolla A, Klenk HD, Sullivan NJ, Volchkov VE, Fritz EA, et al. Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):786–90. doi: 10.1038/nm1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang ZY, Kong WP, Huang Y, Roberts A, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, Nabel GJ. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature. 2004;428(6982):561–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bisht H, Roberts A, Vogel L, Bukreyev A, Collins PL, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, Moss B. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein expressed by attenuated vaccinia virus protectively immunizes mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(17):6641–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401939101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hevey M, Negley D, Pushko P, Smith J, Schmaljohn A. Marburg virus vaccines based upon alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs and nonhuman primates. Virology. 1998;251(1):28–37. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gao W, Tamin A, Soloff A, D’Aiuto L, Nwanegbo E, Robbins PD, Bellini WJ, Barratt-Boyes S, Gambotto A. Effects of a SARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in monkeys. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1895–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Feldmann H, Jones S, Klenk HD, Schnittler HJ. Ebola virus: from discovery to vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(8):677–85. doi: 10.1038/nri1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Geisbert TW, Pushko P, Anderson K, Smith J, Davis KJ, Jahrling PB. Evaluation in nonhuman primates of vaccines against Ebola virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(5):503–7. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cavanagh D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome vaccine development: experiences of vaccination against avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus. Avian Pathol. 2003;32(6):567–82. doi: 10.1080/03079450310001621198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Warfield KL, Swenson DL, Olinger GG, Kalina WV, Aman MJ, Bavari S. Ebola virus-like particle-based vaccine protects nonhuman primates against lethal Ebola virus challenge. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(SUPPL. 2):S430–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Henao-Restrepo AM, Longini IM, Egger M, Dean NE, Edmunds WJ, Camacho A, Carroll MW, Doumbia M, Draguez B, Duraffour S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine expressing Ebola surface glycoprotein: interim results from the Guinea ring vaccination cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):857–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vanderzanden L, Bray M, Fuller D, Roberts T, Custer D, Spik K, Jahrling P, Huggins J, Schmaljohn A, Schmaljohn C. DNA vaccines expressing either the GP or NP genes of Ebola virus protect mice from lethal challenge. Virology. 1998;246(1):134–44. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martin JE, Sullivan NJ, Enama ME, Gordon IJ, Roederer M, Koup RA, Bailer RT, Chakrabarti BK, Bailey MA, Gomez PL, et al. A DNA vaccine for Ebola virus is safe and immunogenic in a phase I clinical trial. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13(11):1267–77. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00162-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Geisbert TW, Geisbert JB, Leung A, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hensley LE, Grolla A, Feldmann H. Single-injection vaccine protects nonhuman primates against infection with Marburg virus and three species of Ebola virus. J Virol. 2009;83(14):7296–304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00561-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Geisbert TW, Jones S, Fritz EA, Shurtleff AC, Geisbert JB, Liebscher R, Grolla A, Ströher U, Fernando L, Daddario KM, et al. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):0537–45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.He Y, Zhou Y, Liu S, Kou Z, Li W, Farzan M, Jiang S. Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces highly potent neutralizing antibodies: Implication for developing subunit vaccine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(2):773–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sullivan NJ, Martin JE, Graham BS, Nabel GJ. Correlates of protective immunity for Ebola vaccines: implications for regulatory approval by the animal rule. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(5):393–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Guillaume V, Contamin H, Loth P, Georges-Courbot MC, Lefeuvre A, Marianneau P, Chua KB, Lam SK, Buckland R, Deubel V, et al. Nipah virus: vaccination and passive protection studies in a hamster model. J Virol. 2004;78(2):834–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.834-840.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chen Z, Zhang L, Qin C, Ba L, Yi CE, Zhang F, Wei Q, He T, Yu W, Yu J, et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region. J Virol. 2005;79(5):2678–88. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2678-2688.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

all data present in this article can be retrieved from Scopus using keywords listed in the methodology.