Abstract

Background

The QT interval on electrocardiogram (ECG) reflects ventricular repolarization; a prolonged QT interval is associated with increased mortality risk. Prior studies suggest an association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and prolonged QT interval. However, these studies were small and often enrolled hospital-based samples. We tested the hypotheses that lower lung function and increased percent emphysema on computed tomography (CT) are associated with a prolonged QT interval in a general population sample and additionally in those with COPD.

Methods

As part of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung Study, we assessed spirometry, full-lung CT scans, and ECGs in participants aged 45–84 years. The QT on ECGs was corrected for heart rate (QTc) using the Framingham formula. QTc values ≥460msec in women and ≥450msec in men were considered abnormal (prolonged QTC). Multivariate regression models were used to examine the cross-sectional association between pulmonary measures and QTC.

Results

The mean age of the sample of 2585 participants was 69 years, and 47% were men. There was an inverse association between FEV1%, FVC%, FEV1/FVC%, emphysema, QTc duration and prolonged QTc. Gender was a significant interaction term, even among never smokers. Having severe COPD was also associated with QTc prolongation.

Conclusions

Our analysis revealed a significant association between lower lung function and longer QTc in men but not in women in a population-based sample. Our findings suggest the possibility of gender differences in the risk of QTc-associated arrhythmias in a population-based sample.

Keywords: QT duration, QT interval, lung function, emphysema, COPD

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), defined as an airflow limitation that does not fully reverse1, is a highly prevalent condition that has robust effects on cardiovascular autonomic function2. The influence is not restricted to the right heart, but affects the entire cardiovascular system through multiple complex interactions. For example, a higher percentage of emphysema-like lung diminishes left ventricular filling, reduces stroke volume and lowers cardiac output3. Lung diseases such as COPD and emphysema may be considered syndromes that include cardiovascular implications, even in the early phases2,4,5.

The autonomic neuropathy seen in lung disease appears to include prolongations of the QT interval, a sign of longer repolarization of the ventricles, which is a risk factor for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or torsade de pointes6. A longer QT interval indicates an abnormal cardiovascular electrical cycle and is linked to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events and mortality7–14.

Whether a similar autonomic neuropathy exists in subclinical lung disease or varies by COPD sub-phenotypes in the general population, remains unknown. Therefore, we examined the association of the QT interval with lung function on spirometry, COPD diagnosis, and the percentage of emphysema-like lung on computed tomography (CT) (hereafter-referred to as percent emphysema) in a diverse population-based cohort. We hypothesized that lower lung function and higher percent emphysema would be associated with a longer QT interval and with abnormally prolonged QT.

METHODS

Study Participants

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a multicenter, prospective cohort study of subclinical cardiovascular disease in Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians (mostly of Chinese origin) without clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline15. Between 2000 and 2002, MESA recruited 6814 men and women 45 to 84 years of age from six U.S. communities.

MESA-Lung is an ancillary study of MESA participants active at follow-up exams 3 or 4. The MESA Lung Study recruited 3,965 participants sampled randomly from MESA. The lung and ECG data analyzed in this study were acquired at the follow-up visit in April 2010–12.

Participants with bundle branch block (defined as QRS duration ≥120msec), atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, a paced rhythm, idioventricular rhythm, or complete heart block on the ECG were excluded. Since we were interested in examining at the association with subclinical measures suggestive of obstructive lung disease, participants with a restrictive pattern on spirometry (pre-bronchodilator forced vital capacity (FVC) less than the lower limit of normal and a FEV1/FVC ratio>0.716) were excluded. This resulted in 2585 participants eligible for analysis.

The institutional review boards of all collaborating institutions and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) approved the protocols of MESA and all studies described herein. All participants provided informed consent.

Measurements

QT Interval

Resting ECGs were recorded in the supine or semi-recumbent position using the GE MAC 1200 electrocardiograph (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) at 10mm/mV and a speed of 25 mm/s. Participants had an overnight fast before the ECGs were recorded. All ECGs were transferred to the MESA Central ECG Reading Center at the Epidemiology Cardiology Research Center (EPICARE), Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston Salem, North Carolina). QT interval was defined as the duration between the earliest QRS onset to the latest T-wave offset. Minnesota code17 was used for classification of ECG abnormalities.

While the QT corrections are susceptible to under- or overestimation of the true QT interval, correcting the QT interval for heart rate is necessary as the QT interval varies with the RR interval: the shorter the RR interval (or the faster the heart rate), the shorter the QT interval. Based on the Recommendations of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram, we used a linear regression function for QT correction18. The model used is the Framingham model19 and was calculated as:

QTc values ≥460 ms in women and ≥450 ms in men are considered abnormal (prolonged QTC)18.

Spirometry

Post-bronchodilator spirometry was conducted in accordance with ATS/ERS guidelines20,21 on a dry-rolling-sealed spirometer (Occupational Marketing, Inc., Houston, TX), as previously described22. Predicted values were calculated using reference equations from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III16,20 with a 0.88 correction for Asians22.

COPD status was defined as a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio<0.7. COPD severity was graded as FEV1≥80% predicted (mild), 50–79% predicted (moderate) or <50% predicted (severe)23. In addition to classifying lung function into categories for COPD severity, lung function was also examined as a continuous parameter. 426 participants could not be classified with respect to COPD because they did not receive a bronchodilator.

Percent Emphysema

Percent emphysema was assessed at suspended full inspiration on the lung fields of full-lung thoracic CT scans as previously described24. Percent emphysema was defined as lung regions below −950 Hounsfield units (HU)25. Emphysema on CT was dichotomized as percent emphysema above the upper limit of normal (ULN) based upon reference equations26.

Sociodemographic and clinical covariates

Information about age, sex, race or ethnicity, and medical history were self-reported. Height and weight were measured following the MESA protocol27. Fasting blood samples were drawn and sent to a central laboratory for measurement of glucose and lipids. Diabetes was coded dichotomously and defined as a fasting glucose level of 126 mg/dL or greater28 or use of medications for diabetes (as assessed by a medication inventory). Resting blood pressure was measured three times in the seated position and the mean of the second and third readings was recorded. Hypertension, treated as a dichotomous variable, was defined by the current use of any antihypertensive medication or by systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg29. Current smoking was categorized as having smoked a cigarette in the previous 30 days30. Possible and definite QT prolonging medications were defined according to the Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics database31.

Statistics

The primary analysis of the association between lung function and QTc duration was determined using linear regression. Logistic regression was used for the secondary analysis with QTc prolongation (dichotomized based on sex-specific thresholds). Models were adjusted for age (in years), gender, race/ethnicity, smoking status, pack years, hypertension, diabetes, education, weight (in pounds), height (in centimeters), and QT prolonging medications (any vs. none). Models for percent emphysema were additionally adjusted for scanner manufacturer and BMI categories (underweight [BMI<20] and obese [BMI≥30] as compared to a normal/overweight reference group [20≤BMI<30]).

The cohort was divided into quintiles based on pre-bronchodilator FEV1 for descriptive purposes. The main exposures of interest were lung function measures: FEV1%, FVC%, and FEV1/FVC% predicted, used continuously; COPD status (any vs none) or severity (mild, moderate and severe vs none), used dichotomously. Pack years showed a skewed distribution and was therefore log transformed to limit the influence of extreme values.

Effect modification by gender and smoking status was considered. The interaction between gender, FEV1% and FVC% was statistically significant (p=0.02), even among never-smokers (p=0.003); therefore, the results were stratified by gender. There was no interaction with smoking status (p=0.54). P-values α≤0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 2585 participants with valid spirometry and ECG data was 69 years, 47% were male, and the race/ethnic distribution was 37% White, 26% African-American, 22% Hispanic and 15% Asian (Table 1). 102 participants had a prolonged QTc- 66 men and 36 women. Of 218 (12%) participants classified as having COPD, 11 had severe COPD, 86 had moderate COPD, and 121 had mild COPD.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants, stratified by gender

| Total | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants n | 2585 | 1371 | 1214 |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 69 (9) | 69 (9) | 69 (9) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), k/m2 | 28.1 (5.4) | 28.5 (6.1) | 27.7 (4.4) |

| Race/ethnicity: | |||

| White, No. (%) | 966 (37) | 502 (37) | 464 (38) |

| African-American, No. (%) | 669 (26) | 376 (27) | 293 (24) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 560 (22) | 302 (22) | 258 (21) |

| Asian, No. (%) | 390 (15) | 191 (14) | 199 (16) |

| Educational attainment: | |||

| No high school degree, No. (%) | 348 (14) | 198 (14) | 150 (12) |

| High school degree, No. (%) | 448 (17) | 278 (20) | 170 (14) |

| Some college, No. (%) | 735 (28) | 418 (31) | 317 (26) |

| College degree, No. (%) | 494 (19) | 240 (18) | 254 (21) |

| Graduate degree or more, No. (%) | 555 (22) | 235 (17) | 320 (26) |

| Cigarette smoking status: | |||

| Never-smokers, No. (%) | 1227 (48) | 780 (57) | 447 (37) |

| Former smokers, No. (%) | 1118 (43) | 491 (36) | 627 (52) |

| Current smokers, No. (%) | 240 (9) | 100 (7) | 140 (12) |

| Smoking history pack-years#, median (IQR) | 14 (3–32) | 12 (3–30) | 15 (3–33) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 1541 (60) | 854 (62) | 687 (27) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 476 (18) | 253 (19) | 223 (18) |

| Post-bronchodilator spirometry: | |||

| FEV1% predicted, mean (SD) | 97 (19) | 97 (20) | 96 (18) |

| FVC% predicted, mean (SD) | 99 (16) | 100 (17) | 99 (15) |

| FEV1/FVC% predicted, mean (SD) | 98 (11) | 98 (11) | 97 (12) |

| Any COPD, No. (%) | 218 (10) | 88 (8) | 130 (13) |

| Mild COPD, No. (%) | 121 (6) | 44 (4) | 77 (8) |

| Moderate COPD, No. (%) | 86 (4) | 39 (4) | 47 (5) |

| Severe COPD, No. (%) | 11 (1) | 5 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Percentage emphysema, median (IQR)* | 1.54 (0.63 to 3.23) | 0.92 (0.44 to 2.01) | 2.45 (1.18 to 4.76) |

| Emphysema ULN, No. (%)* | 263 (9) | 159 (11) | 104 (8) |

| QTc interval msec, mean (SD) | 423 (21) | 429 (19) | 417 (21) |

| Prolonged QTc, No. (%) | 102 (4%) | 36 (3%) | 66 (5%) |

| Heart rate beats/min, mean (SD) | 61 (9) | 62 (9) | 60 (9) |

among ever-smokers

There are 2803 participants with emphysema measures

Lung Function and QT duration

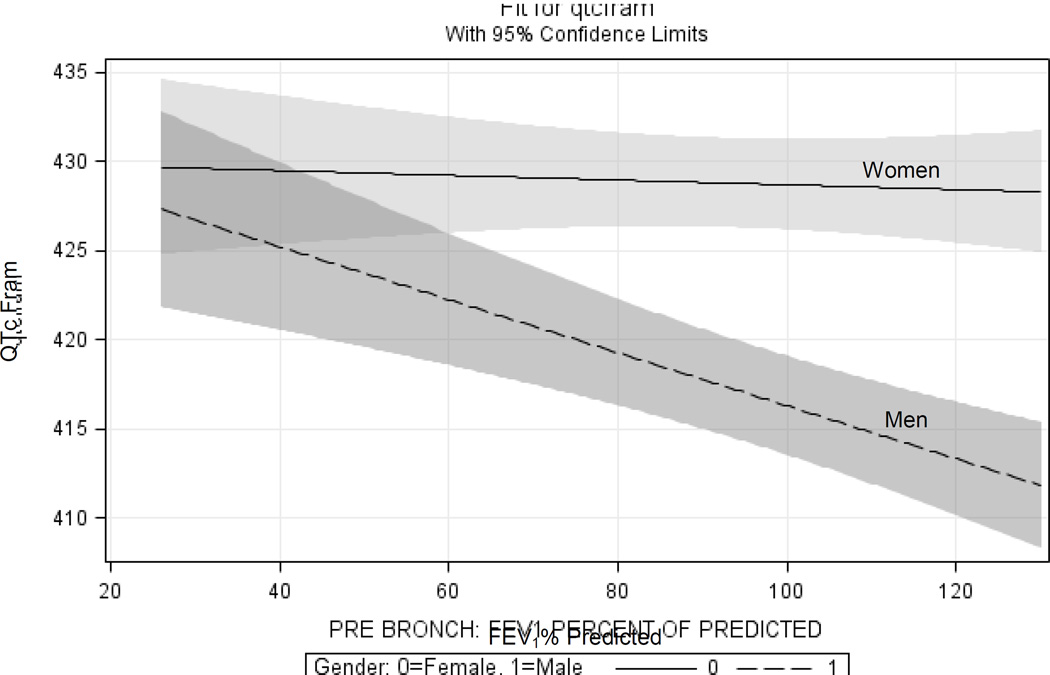

There was a significant inverse association between FEV1% and QTc duration, among men (Figure 1). For a 5-percentage point lower FEV1% predicted, there was a 0.56msec longer QTc (95%CI: 0.23 to 0.88msec; p=0.001). Comparing the lowest quintile of FEV1% to the highest quintile showed an average of a 5.6msec longer QTc duration (95%CI: 1.3 to 9.9msec; p=0.01) (Figure 2A).

Figure 1.

Adjusted Plot for Women and Men with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Models were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education, smoking status, pack-years, hypertension, diabetes, weight, height, and QT altering medications.

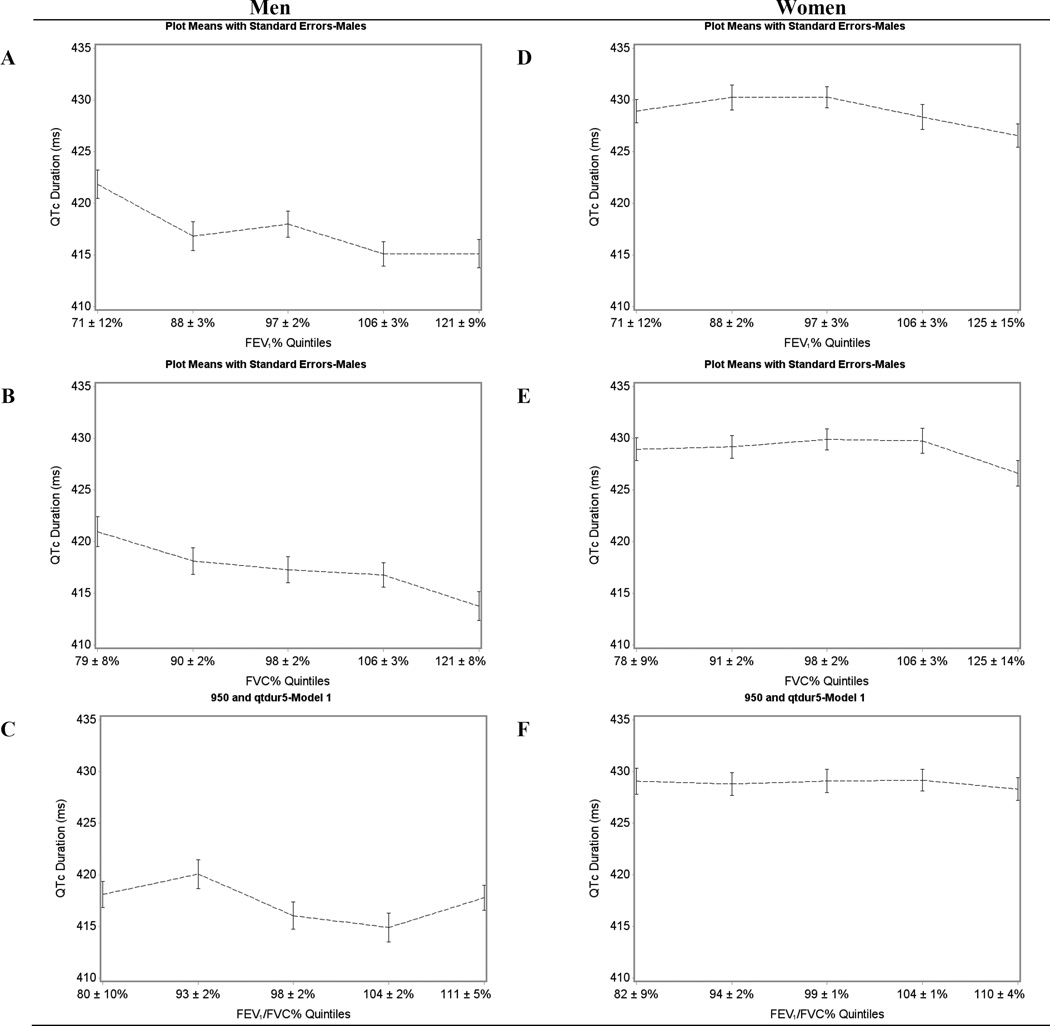

Figure 2.

Predicted Values for Mean Difference in QT According to Quintiles of Percent Predicted Lung Function

Panels A–C: Quintiles of FEV1%, FVC% and FEV1/FVC% for Men.

Panels D–F: Quintiles of FEV1%, FVC% and FEV1/FVC% for Women.

Linear regression adjusted for: age (in years), gender, race/ethnicity, smoking status, pack years, hypertension, diabetes, education, weight (in pounds), height (in centimeters), and QT altering medications

FVC was also significantly associated with QTc duration among men: for a 5-percentage lower FVC% predicted, there was a 0.63msec longer QTc (95%CI: 0.23 to 1.03msec, p=0.002). The lowest FVC% quintile compared to the highest gave an average of a 5.0msec longer QTc (95%CI: 0.54 to 9.4msec; p=0.03) (Figure 2B).

FEV1/FVC% predicted was also inversely associated with QTc in men (Figure 2C). For a 5-percentage lower FEV1/FVC% predicted there was a 0.46msec longer QTc (95%CI: −0.05 to 0.96msec, p=0.08). Interestingly, among women, we did not detect a significant association between any lung function measure and QTc duration (Figures 2D, 2E and 2F). The results for lung function in liters and FEV1/FVC ratio are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean Change in QTc Fram per decrease in lung function

| Variable | Men | p-value | Women | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (L) | 3.7msec (1.35 to 5.97) | 0.002 | 0.33msec (−2.50 to 3.16) | 0.82 |

| FVC (L) | 3.3msec (1.21 to 5.37) | 0.002 | −0.13msec (−2.66 to 2.41) | 0.92 |

| FEV1/FVC | 12.0msec (−1.65 to 25.68) | 0.09 | 0.56msec (−13.52 to 12.39) | 0.93 |

All models are per 1-unit decrease.

Models were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education, smoking status, pack-years, hypertension, diabetes, weight, height, and QT altering medications.

Table 3 shows the odds ratios for prolonged QTc per unit decrement in lung function. For men, lower lung function measures were significantly associated with higher odds of QTc prolongation, but in women only FEV1/FVC% was significantly associated with higher odds of prolonged QTc. Results for lung function in liters are in given in e-Table 1.

Table 3.

Prolonged QTc and lung function

| Variable | Odds ratio for prolonged QTc per 5-percentage point decrease in percent predicted lung function (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Men | ||

| FEV1% | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.18) | 0.01 |

| FVC% | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 0.04 |

| FEV1/FVC % | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.24) | 0.05 |

| Women | ||

| FEV1% | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) | 0.09 |

| FVC% | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) | 0.61 |

| FEV1/FVC% | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.34) | 0.03 |

Prolonged QTc is defined as QTc Fram values of ≥460 ms in women and ≥450 ms in men.

All models are per 5-percentage-point decrease.

Models were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education, smoking status, pack-years, hypertension, diabetes, weight, height, and QT altering medications.

COPD and QT duration

There was no interaction between gender and COPD status on QTc; therefore analyses of COPD were not stratified by gender. There was also no association between COPD severity and continuous QTc. However, having Any COPD vs. No COPD was associated with prolonged QTc (OR= 1.84; 95%CI: 0.94 to 3.62, p-value=0.08). COPD severity categories showed an association with QTc prolongation, after adjustment, only with Severe COPD (Mild COPD vs. No COPD OR=1.92; 95%CI: 0.81 to 4.55, p-value=0.14; Moderate COPD vs. No COPD OR=1.65; 95%CI: 0.55 to 4.94, p-value=0.37; Severe COPD vs. No COPD OR=5.19; 95%CI: 0.97 to 27.79, p-value=0.06).

Emphysema and QT duration

There was no evidence for an interaction with gender and emphysema on CT so it was not stratified. There were 263 participants above and 2540 below the ULN. Emphysema on CT was significantly associated with decreased QTc duration (−2.8msec 95%CI: −5.4 to −0.29msec, p-value=0.03), but there was no evidence that it was associated with prolonged QTc.

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine whether the association between pulmonary function and QTc was present in the general population and not only in those with COPD, we removed those with any COPD from analysis. The associations with QTc were as follows for a 5-percentage lower lung function in men: FEV1%: 0.35msec (95%CI: −0.15 to 0.85msec, p-value= 0.17); FVC%: 0.38msec (95%CI: −0.14 to 0.90msec, p-value=0.15); FEV1/FVC%: 0.09msec (95%CI: −0.87 to 1.05msec, p-value=0.85). The results in liters are given in the Supplement.

DISCUSSION

In a large population-based cohort free of cardiovascular disease at baseline, worse lung function in men measured using spirometry is inversely associated with QTc duration and directly with QTc prolongation. Men with lower values of FEV1%, FVC% and FEV1/FVC% were significantly more likely to have a longer QTc duration and a clinically defined prolonged QTc.. In contrast, emphysema on CT was not associated with QT prolongation.

For both genders, while there was no significant graded association between COPD severity categories and QTc, QTc was prolonged in participants with severe COPD and in those with Any COPD vs. No COPD. The absence of an association of graded severity of COPD with QTc is not new, as this is seen in previous studies assessing autonomic dysfunction in patients with COPD32,33. Tug et al. assessed the relationship between the frequency of autonomic dysfunction in mild and moderate-severe COPD groups. Although it was found that dysfunction was predominant in COPD, the frequencies of autonomic parasympathetic and sympathetic dysfunction did not increase with the severity of COPD32. An additional study of 243 patients with COPD found that although ECG abnormalities increased with disease severity, it was not significant33.

The association of reduced lung volumes with cardiovascular disease has been widely recognized but predominantly studied in regards to severe COPD patients5,34–38. Much like our study, except in a small population of only patients with COPD, a study assessing the frequency of autonomic dysfunction found that those with lower lung function had significantly more autonomic dysfunction32. Studies involving mild to moderate COPD patients are typically limited to small sample sizes, do not control for confounders or have no direct pulmonary function measures5,32,33. Our large-scale study had spirometry, and includes possible confounders, such as QT prolonging medications, comorbidities such as diabetes, and is a sample of the general population. Our results suggest that the association of reduced lung function with autonomic dysfunction extends to those with only slight lung impairment. Although associations of lung function measures with QTc were not significant in our sensitivity analysis that excluded participants with COPD, that analysis was likely underpowered as evidenced by the increase in confidence intervals and that the effect estimates were consistent.

Loss of elastic tissue, from factors such as cigarette smoking, increases resistance to airflow, thereby increasing intrathoracic pressure. These pressure changes can also affect the sympathetic drive; and while the exact mechanism is unknown, prolongation of the QT interval is thought to be due to an imbalance in the sympathetic drive13,32. However, this increase in pressure is unlikely to explain the association between reduced lung function and QT prolongation seen in our study of the general population. We observed unexpected results for the association between emphysema and QTc duration. As the rest of our analysis is consistent, this is most likely due to chance.

It was interesting to note the gender differences seen in this study. While there were more former and current smokers among men, when we looked at never smokers, there was a significant interaction of gender with FEV1% on QTc. It has been documented that the QT interval tends to be longer in women than men39, which was also seen in this study as women had an average QTc of 429(19) msec while men had an average of 417(21) msec. After puberty, in men there is a 20 msec drop in QTc values, whereas QTc values of women remain stable40. What is intriguing in our study is the fact that only in men did the linear association with QTc interval increase with a decrease in pulmonary function. Further studies are warranted to determine the mechanism behind the gender difference between QTc duration and lung function.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional analysis with concurrent assessment of both exposure and outcome, limiting the temporal associations. Additionally, some participants were missing post-bronchodilator measures. Although the continuous pulmonary function measures were significantly associated with QTc and some association was seen with the severity of COPD, the categories of COPD severity were not statistically significant after adjustment.

While measurements were taken at only one follow-up visit, the study’s sample was large and a substantial majority of the subjects had pre and post bronchodilator values for the determination of COPD and follow the GOLD criteria for classification. This population-based sample is ethnically diverse and free of cardiovascular disease at baseline. Additionally, participants were not selected based on the presence or absence of lung disease, allowing wide variation in lung function.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated an association among men in the general population between lower FEV1% and FVC% and longer QT duration. Low lung function may be a risk factor for longer QT in the general male population, even in those without lung disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

2585 participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung Study with spirometry, full-lung CT scans, and ECGs were analyzed. Multivariate regression models were used to examine the cross-sectional association between pulmonary measures and QTC.

There was an inverse association between FEV1%, FVC%, FEV1/FVC%, emphysema, QTc duration and prolonged QTc. Gender was a significant interaction term, even among never smokers. Having severe COPD was also associated with QTc prolongation.

Our analysis revealed a significant association between lower lung function and longer QTc in men but not in women in a population-based sample. Our findings suggest the possibility of gender differences in the risk of QTc-associated arrhythmias in a population-based sample.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) (HL077612, HL093081, N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95169) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant Number UL1 TR000040). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CT

Computed tomography

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- HU

Hounsfield units

- MESA

Multi Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- SPIROMICS

Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts exist for all authors

Prior abstract publication: American Thoracic Society Conference, Denver, CO; May 2015.

HFA and RGB had full access to the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. HFA, GSL, EZS, SRH, JHMA and RGB made substantial contributions to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors drafted the submitted article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zulli R, Donati P, Nicosia F, et al. Increased QT dispersion: a negative prognostic finding in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2006;1(4):279–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02934761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Ahmed FS, et al. Percent Emphysema, Airflow Obstruction, and Impaired Left Ventricular Filling. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(3):217–227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart A, Waterhouse J, Howard P. Cardiovascular autonomic nerve function in patients with hypoxaemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European Respiratory Journal. 1991;4(10):1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhabra SK, De S. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine. 2005;99(1):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morganroth J. Relations of QTc prolongation on the electrocardiogram to torsades de pointes: Definitions and mechanisms. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1993;72(6):B10–B13. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Algra A, Tijssen JG, Roelandt JR, Pool J, Lubsen J. QTc prolongation measured by standard 12-lead electrocardiography is an independent risk factor for sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Circulation. 1991;83(6):1888–1894. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giunti S, Gruden G, Fornengo P, et al. Increased QT Interval Dispersion Predicts 15-Year Cardiovascular Mortality in Type 2 Diabetic Subjects: The population-based Casale Monferrato Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):581–583. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bruyne MC, Hoes AW, Kors JA, Hofman A, van Bemmel JH, Grobbee DE. Prolonged QT interval predicts cardiac and all-cause mortality in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. European Heart Journal. 1999;20(4):278–284. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montanez A, Ruskin JN, Hebert PR, Lamas GA, Hennekens CH. Prolonged qtc interval and risks of total and cardiovascular mortality and sudden death in the general population: A review and qualitative overview of the prospective cohort studies. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(9):943–948. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawicki PT, DÄhne R, Bender R, Berger M. Prolonged QT interval as a predictor of mortality in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 1996;39(1):77–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00400416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp DS, Masaki K, Burchfiel CM, Yano K, Schatz IJ. Prolonged QTc Interval, Impaired Pulmonary Function, and a Very Lean Body Mass Jointly Predict All-Cause Mortality in Elderly Men. Annals of Epidemiology. 1998;8(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart AG, Waterhouse JC, Howard P. The QTc interval, autonomic neuropathy and mortality in hypoxaemic COPD. Respiratory Medicine. 1995;89(2):79–84. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(95)90188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beinart R, Zhang Y, Lima JAC, et al. The QT Interval Is Associated With Incident Cardiovascular Events. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64(20):2111–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric Reference Values from a Sample of the General U.S. Population. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackburn H, Keys A, Simonson E, Rautaharju P, Punsar S. The Electrocardiogram in Population Studies: A Classification System. Circulation. 1960;21(6):1160–1175. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.21.6.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS. AHA/ACCF/HRS Recommendations for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram: Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53(11):982–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengtson JR, Levy D. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 1992;70(7):797–801. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90562-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(3):511–522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankinson JL, Kawut SM, Shahar E, Smith LJ, Stukovsky KH, Barr RG. Performance of american thoracic society-recommended spirometry reference values in a multiethnic sample of adults: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa) lung study. CHEST Journal. 2010;137(1):138–145. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: A summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. European Respiratory Journal. 2004;23(6):932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couper D, LaVange LM, Han M, et al. Design of the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcomes in COPD Study (SPIROMICS) Thorax. 2014;69(5):492–495. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gevenois PA, de Maertelaer V, De Vuyst P, Zanen J, Yernault JC. Comparison of computed density and macroscopic morphometry in pulmonary emphysema. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;152(2):653–657. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman EA, Ahmed FS, Baumhauer H, et al. Variation in the Percent of Emphysema-like Lung in a Healthy, Nonsmoking Multiethnic Sample: The MESA Lung Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2014;11(6):898–907. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-364OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NHLBI M-. Exam 5 Field Center Procedures Manual of Operations. 2010 http://www.mesanhlbi.org/publicdocs/2011/mesae5_mopjanuary2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diagnosis TECot, Mellitus* CoD. Follow-up Report on the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3160–3167. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The sixth report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(21):2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez J, Jiang R, Johnson WC, MacKenzie BA, Smith LJ, Barr RG. The Association of Pipe and Cigar Use With Cotinine Levels, Lung Function, and Airflow Obstruction A Cross-sectional Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152(4):201–210. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics. QT Drug Lists by Risk Groups: Drugs That Prolong the QT Interval and/or Induce Torsades de Pointes Ventricular Arrhythmia. Tuscon, AZ: Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics; [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tug T, Terzi SM, Yoldas TK. Relationship between the frequency of autonomic dysfunction and the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2005;112(3):183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnier MJ, Rutten FH, Numans ME, et al. Electrocardiographic Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2013;10(1):62–71. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.727918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curkendall S, Lanes S, Luise C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;21(11):803–813. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkelstein J, Cha E, Scharf SM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2009;4:337–349. doi: 10.2147/copd.s6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider C, Bothner U, Jick SS, Meier CR. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of cardiovascular diseases. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;25(4):253–260. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry JCP, DeLuise C, Lanes S, Eisner MD. Copd and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser permanente medical care program*. CHEST Journal. 2005;128(4):2068–2075. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange P, Mogelvang R, Marott JL, Vestbo J, Jensen JS. Cardiovascular Morbidity in COPD: A Study of the General Population. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2010;7(1):5–10. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burke JH, Ehlert FA, Kruse JT, Parker MA, Goldberger JJ, Kadish AH. Gender-Specific Differences in the QT Interval and the Effect of Autonomic Tone and Menstrual Cycle in Healthy Adults. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1997;79(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rautaharju PM, Zhou SH, Wong S, et al. Sex differences in the evolution of the electrocardiographic QT interval with age. Can J Cardiol. 1992;8(7):690–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.