Abstract

Minimal tillage management of extensive crops like wheat can provide significant environmental services but can also lead to adverse interactions between soil borne microbes and the host. Little is known about the ability of the wheat cultivar to alter the microbial community from a long-term recruitment standpoint, and whether this recruitment is consistent across field sites. To address this, nine winter wheat cultivars were grown for two consecutive seasons on the same plots on two different farm sites and assessed for their ability to alter the rhizosphere bacterial communities in a minimal tillage system. Using deep amplicon sequencing of the V1–V3 region of the 16S rDNA, a total of 26,604 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were found across these two sites. A core bacteriome consisting of 962 OTUs were found to exist in 95% of the wheat rhizosphere samples. Differences in the relative abundances for these wheat cultivars were observed. Of these differences, 24 of the OTUs were found to be significantly different by wheat cultivar and these differences occurred at both locations. Several of the cultivar-associated OTUs were found to correspond with strains that may provide beneficial services to the host plant. Network correlations demonstrated significant co-occurrences for different taxa and their respective OTUs, and in some cases, these interactions were determined by the wheat cultivar. Microbial abundances did not play a role in the number of correlations, and the majority of the co-occurrences were shown to be positively associated. Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States was used to determine potential functions associated with OTUs by association with rhizosphere members which have sequenced metagenomics data. Potentially beneficial pathways for nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and malate metabolism, as well as antimicrobial compounds, were inferred from this analysis. Differences in these pathways and their associated functions were found to differ by wheat cultivar. In conclusion, our study suggests wheat cultivars are involved in shaping the rhizosphere by differentially altering the bacterial OTUs consistently across different sites, and these altered bacterial communities may provide beneficial services to the host.

Keywords: rhizosphere, microbiome, OTU, wheat, microbial community

Introduction

The roots of land plants are surrounded by complex communities of microorganisms (Tringe et al., 2005; Peiffer et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2015). There is a growing body of evidence that the root rhizosphere is a crucial zone for many host–microbe interactions (Zachow et al., 2014; Bulgarelli et al., 2015; Tkacz et al., 2015; Müller et al., 2016; Saleem et al., 2016). Many of these interactions are mutualistic. For example, plants benefit from mobilization of minerals (Vangronsveld et al., 2009; Sessitsch et al., 2013; Plociniczak et al., 2016) and other inorganic molecules, while the microbes benefit from root exudates which provide an energy source in the form of sugars and organic acids (Bais et al., 2006; van Dam and Bouwmeester, 2016). Plant hosts further benefit from microbes with improved growth (Bashan et al., 2014; Glick, 2014), drought and salt tolerance (Castiglioni et al., 2008; Kasim et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014; Naveed et al., 2014; Sarma and Saikia, 2014; Pinedo et al., 2015), and protection against soilborne pathogens (Weller et al., 2002; Cha et al., 2015; De Boer et al., 2015). There is further evidence to suggest that some of these microbial interactions are driven by root exudates, such as malic and hydroxamic acids, benzoxazinoids, and other phytochemicals (Neal et al., 2012; Badri et al., 2013; Carvalhais et al., 2013, 2015; Yin et al., 2013).

The use of high-throughput sequencing and microbial-specific databases have allowed for greater characterization of the bacterial rhizosphere communities. It is possible to classify soil microbes down to the level of species or operational taxonomic unit (OTU) using microbial specific databases and efficient clustering algorithms. Next generation sequencing technologies have allowed for deeper sequencing of the microbial communities over previous methods, such as terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (TRFLP). These newer approaches have provided better insights into the assemblage of the community in terms of alpha and beta diversity (Peiffer et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2015). The use of beta diversity analyses, such as ordination, have helped to describe the microbial community patterns over differing habitats such as field locations and by specific host genotypes (Berg and Smalla, 2009; Peiffer et al., 2013; Zachow et al., 2014; Edwards et al., 2015). However, these ordinations only partially address some of the connections between the microbial taxa and their habitats. Newer methods like co-occurrence networks provide better insights into how these species co-occur, either positively or negatively, and the functional roles they have in the habitat (Cardinale et al., 2015).

Recently, co-occurrence networks were used to determine non-random associations between bacterial taxa and their plant hosts (Cardinale et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2015; Kuebbing et al., 2015; Tu et al., 2016). This method was further complemented with analyzing functional metagenomic data of sequenced bacterial genomes that were associated with species of interest using 16S rDNA markers (Langille et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2016). The informative data these analyses provide could be used to characterize microbial species that may benefit host-plant through environmental services, such as mineral mobilization, nutrient assimilation or antimicrobial production (Wissuwa et al., 2009; Langille et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2016; Raaijmakers and Mazzola, 2016). Microbial studies involving crop species such as maize, rice, and wheat have provided insight into how different bacterial communities respond to host, location, plant growth stage, field management strategies, and soil conditions (Peiffer et al., 2013; Donn et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2015; Corneo et al., 2016). Studies characterizing the bacterial communities of wheat roots have demonstrated host-dependent and cropping effects. For example, the age of a host plant, and crop rotations can impact the bacterial communities of wheat (Yin et al., 2010; Donn et al., 2015). There is further evidence that tillage management, such as conventional tillage versus minimal tillage may alter the microbial community and their diversity (Navarro-Noya et al., 2013), including the OTU level (Yin et al., 2010). Wheat is grown on more acres than any other crop (FAO, 2015) allowing for an excellent opportunity to manipulate soil biology and microbial communities through host-dependent mechanisms.

We hypothesized that deeper sequencing and more cultivars would provide better insights into host-associated recruitment, and a “bacteria core” for the wheat rhizosphere, particularly in the high rainfall zone of the inland Pacific Northwest (PNW). We also explored the functional potential of the community by using 16S rDNA marker gene associations with species with extensive functional and genomic characterization (Langille et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2016). Lastly, we searched what is known about functions of OTU we found to be responsive to specific wheat cultivars to reveal the potential of wheat breeding to enhance microbial communities for purposes like disease suppression.

Materials and Methods

Site Description and Soil Sampling

Two comparable field trials were established on adjacent farms with similar soils but different cropping histories near Pullman, WA, USA. The field sites, approximately 1000 m apart, were established in 2008 (46°47′07.6″N 117°05′21.6″W) at the Cook Agronomy Farm and 2012 (46°46′38.0″N 117°04′57.4″W) at the Plant Pathology Farm. The soil for the two locations is classified as Palouse-Thatuna silt loams, had an average pH of 6.5, and received an average of 462 mm of precipitation annually from 2008 to 2010, and 482 mm from 2012 to 2014 (Supplementary Table 1). The average temperature of the Cook and the Plant Pathology farm for 2008 to 2010 was 8.8°C and for 2012 to 2014 was 9.1°C (Supplementary Table 1). The Cook Agronomy Farm site occupied a slight north facing slope and was previously cropped with spring pea (Pisum sativum). While the site at the Plant Pathology Farm was a flat area at the bottom of mild north and south facing slope, and was previously cropped with a mix of winter wheat cultivars. Plot locations were fertilized using a commercial formula (McGregor Company, Colfax, WA, USA) mixed at an 8–3 ratio. This mixture was applied at a rate of 89.6 kg of nitrogen, 16.8 kg of phosphorus, and 13.5 kg of sulfur per hectare. Winter wheat lines varying in pedigree (Table 1), were grown in 1.5-m × 1.5-m plots. Four of the lines consisted of two pairs of near isogenic lines either carrying the ALMT1 (ALuminum-activated Malate Transporter 1) gene in the Chisholm or Century background (PI561722 and PI561725, respectively) or the almt1 allele in the same backgrounds (PI561726 and PI561727, respectively) (Sasaki et al., 2004; Lakshmanan et al., 2013). An additional five lines were well-established wheat cultivars in the PNW, grown on many acres, and determined in greenhouse tests to have different effects on suppression of Rhizoctonia species, possibly through alteration of microbial communities (Mazzola and Gu, 2002; Gu and Mazzola, 2003). Approximately 250 g of each cultivar (1000-seed weights, Table 1) were hand sown into five manually dug, 5 cm deep trenches during October of each year. Plots of each cultivar were replicated three times in a randomized block design for both sites. In the first growing season, whole plants were harvested at maturity approximately 10-cm from the ground during September of each year and the same cultivar replanted into previous plant stubble as to best mimic a continuous minimal tillage system. Plots were managed by manually removing weeds.

Table 1.

Pedigrees of winter wheat cultivars that were tested for associated operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at two locations and 1000-seed weights for each cultivar.

| Cultivar | Pedigree | Market Class1 | Year2 | 1000-seed weight3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eltan | Luke//BR-70443-4, PI167822/CI013438 | SWW | 1990 | 41.1 |

| Finch | Dusty/IWA7164/Dusty | SWW | 1987 | 40.5 |

| Hill81 | YAMHILL/HYSLOP | SWW | 1981 | 41.2 |

| Lewjain | LUKE(CI-14586)/WA-5829 | SWW | 1982 | 37.6 |

| Madsen | VPM-1/MOISSON-951//2∗HILL-81 | SWW | 1988 | 40.1 |

| PI561722 | Chisholm∗4/Atlas 66 (Al tolerant) | HRW | 1992 | 41.5 |

| PI561725 | Century∗4/Atlas 66 (Al tolerant) | HRW | 1992 | 40.6 |

| PI561726 | Chisholm∗4/Atlas 66 (Al susceptible) | HRW | 1992 | 39.8 |

| PI561727 | Century∗4/Atlas 66 (Al susceptible) | HRW | 1992 | 40.2 |

1Market class abbreviation; hard red winter (HRW) and soft white winter (SWW). 2Refers to the year that cultivar or germplasm was released. 3Mass of 1000 seeds in grams.

Soil Rhizosphere Collection

In the 2nd year for each trial, roots from five to ten randomly selected individuals were harvested at the reproductive stage from each plot in late May to early June. Samples were collected by manually digging around each plant to a depth of 20–30 cm. Tillers and bulk plant material were cut and roots with a partially attached stem were then placed into plastic bags. For 2010 and 2014, root samples were collected from five plants of each cultivar per plot. Roots with the majority of the bulk soil removed were placed into a 50-ml plastic tube with 20 ml of sterile distilled water. To collect the rhizosphere soil, each tube was vortexed for 60 s and sonicated for an additional 60 s. Bulk roots were then removed from the tubes using sterile forceps and the tubes centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min to pelletize the soil. After the supernatant was removed, the pellet (approximately ≤ 0.25 g) was added to a PowerBead tube, a component of the PowerSoil DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA was extracted following manufacturer protocol. DNA was stored at -20°C.

Sequencing and Processing of Reads

DNA samples were sent to Molecular Research (MRDNA, Shallowater, TX, USA). The V1–V3 region of the 16S rDNA gene was amplified using barcoded 27F (5′-AGAGTTT GATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 518R reverse (5′-ATTACCGCG GCTGCTGG-3′) primers. These primers were chosen as the V1–V3 region has been to found to provide good coverage for bacterial community reconstruction (Yu and Morrison, 2004; Kumar et al., 2011), and captures high levels of rhizosphere soil diversity for bacterial taxa (Peiffer et al., 2013). Amplification was performed using HotStar Taq Plus Master Mix Kit and the following conditions: 94°C for 3 min; following 28 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min. Samples were purified and pooled after being checked on a 2% agarose gel for relative intensity and size.

Libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq DNA library kit and following manufacture’s protocol. Amplicons were paired-end sequenced using 300 bp chemistry on the Illumina MiSeq, using standard sequencing controls. Sequences were processed using the Molecular Research’s pipeline. Briefly, paired-end reads were merged, denoised and samples with a quality score < 25 and homopolymers > 8 were removed. Samples were de-multiplexed and downloaded for use with sequence reads separated into samples (sequences per sample, Supplementary Table 2).

Operational Taxonomic Unit Processing and Assignment

Sequences from each sample were trimmed of primers, barcodes, and to a length of 350 nt from the 3′ end. Sequences less than 350 nt were removed. Samples were merged into a single file for OTU clustering. Sequences were subjected to chimeric detection using UCHIME implemented in USEARCH ver. 7 (Edgar, 2013). Filtered sequences were then trimmed and clustered into OTUs using a >97% similarity and the UPARSE pipeline (Edgar, 2013) with the removal of singletons.

The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier (Cole et al., 2009) was used to classify the most abundant representative OTU sequence with RDP (ver. 2.12) and Greengenes 16S rDNA references using MICrobial Community Analysis (MICCA, Albanese et al., 2015). Sequences that classified as plastidal (e.g., chloroplast) or mitochondrial were removed from further analysis. The OTU table was normalized by two methods; samples were rarefied to a read depth of 20,365 and relative abundance was calculated by dividing the number of each OTU by the total number of sequences in a sample. To identify OTUs that occurred in 95% of the wheat rhizosphere samples, QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010) and the script, compute_core_microbiome.py was used.

Co-occurrence Networks and Functional Metagenome Predictions

The co-occurrence networks were constructed using Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003) and the CoNet plug-in (Faust et al., 2012). Spearman’s correlations using thresholds set at ≥ 0.8 or ≤-0.8, and a P < 0.01 were used to determine correlations.

The functional metagenome predictions were based on the algorithm implemented in Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) 1.0.0 (Langille et al., 2013). The sequences were clustered and assigned to the Greengenes reference (ver. 13.5) at a 97% similarity level. The rarefied OTU table and the PICRUSt standard operating protocol with scripts, normalize_by_copy_number, predict_metagenomes, and categorize_by_function, were used to produce a table of the functional gene content of KEGG Orthology (KO) terms and pathways, defined to level 3. Sulfur, phosphate, nitrogen, and antimicrobial KEGG pathways were chosen to determine genotypic enrichment. Sequence counts associated with malate related pathways were analyzed to determine if there were differences in bacterial responses by the aluminum tolerant wheat cultivars. Reference pathways were searched in the KEGG database4 and all associated KO terms for specific pathways were compiled and used for wheat cultivar analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To determine significant differences in the relative abundances of cultivar-associated phyla, OTU, locations and their interactions, data was log(x+1) transformed, and a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) test in PRIMER (v7, PRIMER-E, Plymouth, UK) was run, using a Bray–Curtis similarity resemblance and 999 permutations. Any significant differences were further tested using pair-wise tests in PRIMER. All other statistical differences between samples were compared using paired t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or a non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis test) in JMP (ver 12. SAS, NC). Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) or Steel-Dwass All Pairs implemented in JMP12 were used to determine cultivar differences based upon parametric or non-parametric one-factor data, respectively. An OTU relative abundance cut-off of 0.01% was used to calculate wheat cultivar differences and a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) at P < 0.10 [corresponding to an uncorrected alpha (P) = 0.02] was used to correct for multiple hypothesis testing. To determine the difference for wheat cultivars based on the post hoc analysis, a wheat cultivar with the same letter and no significant difference across locations, were indicators for an effect.

Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCO) was conducted using OTU relative abundances in the rhizosphere of different wheat cultivars and the two field sites. The PCO was visualized by using log(x+1) data transformation and Bray–Curtis resemblances measures in PRIMER. OTUs with significantly different frequencies across cultivars or locations were plotted using Pheatmap in R. Spearman correlations for network analysis were conducted by plotting rank-order of relative abundance against the number of co-occurrences in JMP12. Rarefied sequence count data (required for PICRUSt) was used for metagenomics functional analyses. KO terms for different wheat cultivars were compared using data from PICRUSt and analyzed in the program Statistical Analysis of Taxonomic and Functional Profiles (STAMP, Parks and Beiko, 2010). The Benjamini–Hochberg FDR was used to correct for multiple testing. Differences were further tested in JMP (ver.12) using Tukey’s HSD to determine wheat cultivar effects.

Results

Rhizosphere OTU Composition and Core Bacteria

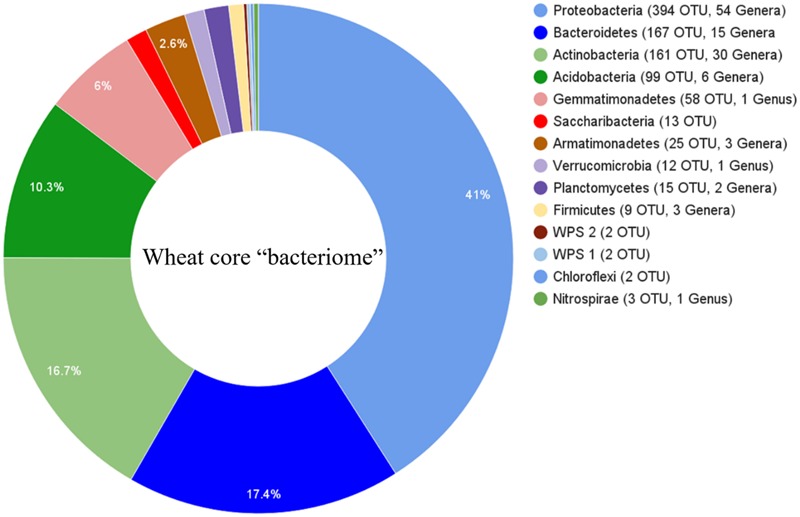

Sequence comparisons of the V1–V3 region of 16S rDNA genes were used to assess the bacterial rhizosphere communities of nine wheat cultivars grown in two locations. After trimming and quality filtering, a total of 5,522,528 reads 350 bp in length were obtained from the 54 rhizosphere samples. These sequences clustered into 26,604 OTUs using a 3% dissimilatory threshold. The core rhizosphere consisted of 962 OTUs, which were found in 95% of wheat cultivar samples, and included phyla Proteobacteria (with 394 OTUs), Bacteroidetes (167), Actinobacteria (161), Acidobacteria (99), Gemmatimonadetes (58), Armatimonadetes (25), Planctomycetes (15), Candidatus Saccharibacteria (13), Verrucomicrobia (12), Firmicutes (9), Incertae_sedis (4), Nitrospirae (3) and Chloroflexi (2) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic distributions of bacterial operational taxonomic unit (OTUs) that were presented in at least 95% of rhizosphere samples across all cultivars and their locations. Phyla are listed with number of OTUs and the number of classifiable taxa associated with each phylum.

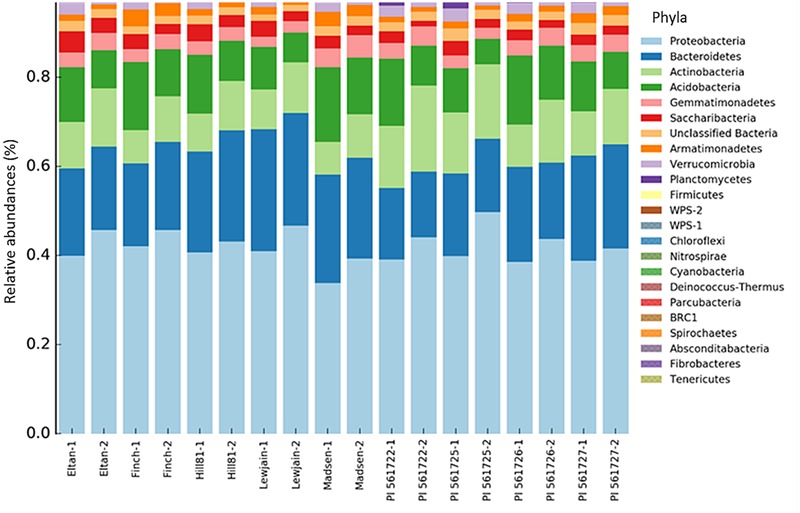

Comparative Analysis of Wheat Cultivars

Across the nine wheat cultivars, 26 Phyla were found using the RDP classification. Of these phyla, two comprising more than 65% of the total sequence reads were identified as Proteobacteria (mean = 49.4%) and Bacteroidetes (mean = 20.8%). Differences in the relative abundance for certain phyla were found between the wheat cultivars. A higher abundance for Planctomycetes (P < 0.001) was observed for Eltan, PI561722, and PI561725. Cultivars Finch, Madsen, and PI561726 had more classified Acidobacteria relative abundances (P = 0.001) in their rhizospheres. The phyla Actinobacteria was found to be in greater abundance in the rhizospheres of PI561722 and PI561725 (P = 0.001). Smaller differences in abundance were observed for Chloroflexi (P = 0.01), Fibrobacteres (P = 0.021), and Verrucomicrobia (P = 0.041) for multiple wheat cultivars (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Bacterial taxonomic assignments at the phyla level and their percentage contribution (abundance) in the rhizosphere soil of different wheat cultivars at two locations (Cook Farm, 1, and Plant Pathology Farm, 2).

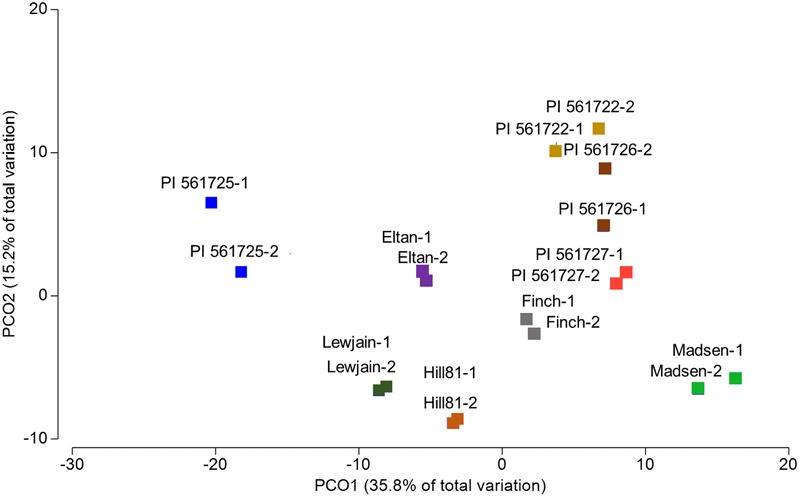

To investigate if there were significant differences in the relative abundances of cultivar- associated OTUs, a PERMANOVA test statistic was conducted to determine the effect of plant cultivar and field site on variation in the relative abundances of the OTUs. A significant effect was found for cultivar (P = 0.001, 997 perms,) and for location (P = 0.007, 999 perms). No significant interaction was determined by these two factors (P = 0.875, 997 perms, Table 2). To visualize these differences, a principle coordinate analysis plot was produced using relative abundances from the Bray–Curtis similarity measures. Several of the wheat cultivars were well separated indicating differences in the relative abundances of OTUs in their rhizosphere communities (Figure 3). The first two principle coordinates explained about 51% of the variation among the 18 cultivar/location treatments. Axis one explained the major source of variation (35.8%) and appeared mainly to correspond to differences in host cultivar (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) of main factors tested and their interactions for the wheat rhizosphere.

| Sources of variation | Df | Sum of squares | Mean squared | Pseudo-F | P-value | Permutations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phyla | |||||||

| Cultivar | 8 | 1808 | 106.4 | 1.69 | 0.013 | 990 | |

| Location | 1 | 1408 | 151.2 | 1.12 | 0.252 | 999 | |

| OTUa | |||||||

| Cultivar | 8 | 12840 | 1604.9 | 2.23 | 0.001 | 997 | |

| Location | 1 | 2502.1 | 2502.1 | 3.47 | 0.007 | 999 | |

| Cultivar × location | 8 | 1049.9 | 131.2 | 0.18 | 0.875 | 997 | |

aOperational taxonomic unit (≥ 97% sequence similarity).

FIGURE 3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCO) based on rhizosphere abundances of OTUs for cultivars which were sampled in two locations (Cook Farm, 1, and Plant Pathology Farm, 2).

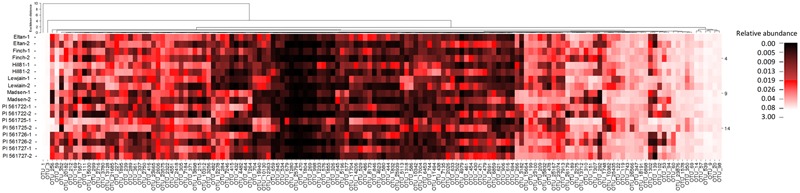

To identify host-associated OTUs that were different between the nine cultivars, and provide a more reproducible analysis, we removed from the analysis all OTUs which did not have a relative abundance greater than 0.01% when averaged over all treatments. This reduced the number of OTUs from 26,604 to 1305. Of these 1305, differences with location and/or wheat cultivar were found for 148 OTUs (P < 0.01, Figure 4). Twenty-four OTUs, representing 2.4% of the total normalized rhizosphere sequences, were found to be significantly enriched or depleted on specific wheat cultivar in both fields (Table 3). The cultivar-associated OTUs were not limited to a specific clade but rather came from most of the abundant phyla, including Acidobacteria (2 OTU), Actinobacteria (2), Bacterioidetes (9), Gemmatimonadetes (3), Proteobacteria (8), and Verrucomicrobia (1) (Table 3).

FIGURE 4.

A heat map displaying the frequencies of OTUs with an average relative abundance ≥ 0.01% in rhizosphere soils of different cultivars listed are noted by the two different locations (Cook Farm, 1, and Plant Pathology Farm, 2) in which they were sampled.

Table 3.

Twenty-four cultivar-associated OTUs using a false discovery rate (Benjamini–Hochberg) and Tukey’s HSD for wheat cultivars grown at two farms for two consecutive years.

| OTU_ID1 | Phylum | Class | Genus | Accession2 | Cultivar-associated3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTU_212 | Acidobacteria | Acidobacteria Gp1 | Gp1 | JX694540 | Hill81 |

| OTU_17004 | Acidobacteria | Acidobacteria Gp1 | Gp1 | JQ381822 | Hill81 |

| OTU_59 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Amycolatopsis | DQ076483 | Hill81 |

| OTU_10130 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Arthrobacter | KM434258 | PI561725 |

| OTU_1302 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacteria | Chryseobacterium | JX987481 | PI561725 |

| OTU_256 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacteria | Flavobacterium | NR133746 | PI561725 |

| OTU_292 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Dyadobacter | EF516729 | PI561725 |

| OTU_310 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Ferruginibacter | JF139728 | PI561725 |

| OTU_19940 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Ferruginibacter | JX172038 | PI561725 |

| OTU_1318 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Mucilaginibacter | AF409002 | Lewjain |

| OTU_1748 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Mucilaginibacter | HE819800 | Madsen |

| OTU_11521 | Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Pedobacter | HM049699 | PI561725 |

| OTU_743 | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonas | HQ118407 | Madsen |

| OTU_347 | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonas | JQ369813 | Madsen |

| OTU_15664 | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonas | HQ118407 | Madsen |

| OTU_119 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Methylosinus | JF910921 | Madsen |

| OTU_1895 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Microvirga | JX777929 | Hill81 |

| OTU_1832 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Sphingomonas | JX776177 | PI561725 |

| OTU_6898 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Sphingomonas | AM936331 | PI561727 |

| OTU_252 | Proteobacteria | Betaproteobacteria | Shinella | AM697120 | PI561725 |

| OTU_11409 | Proteobacteria | Betaproteobacteria | Variovorax | KM877167 | PI561725 |

| OTU_744 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Dokdonella | JF910515 | Hill81 |

| OTU_13128 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Lysobacter | JX112990 | Lewjain |

| OTU_1134 | Verrucomicrobia | Opitutae | Opitutus | HM723529 | Madsen |

1Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) were assembled based on 97% sequence similarity.

2Closest BLASTn match to the NCBI database using the most abundant OTU representative and selecting the first or lowest E-value.

3The cultivar in which the OTU was most highly associated (abundant).

Observations with Cultivar-Associated OTU and Rhizoctonia Suppression

To identify cultivar-associated OTUs in our dataset which correspond to bacterial isolates shown to be suppressive to the soilborne pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG8, the most abundant V1–V3 sequence from the cultivar-associated OTUs were pairwise aligned with the cloned sequences from the suppression study. The previously isolated bacteria came from a very different soil type from a much lower rainfall region of Washington. OTU_1302 (Table 3) had a 97.2% sequence identity to the isolate 31 of Chryseobacterium soldanellicola (previously designated OTU437) indicating isolate 31 is a representative of this OTU. A second isolate of C. soldanellicola that was found to be suppressive (previously designated OTU18, isolate 43), had the closest sequence to OTU_1302 but was less than 97% identical (96.2%). OTU_11521 (Table 3) had a 91.7% sequence similarity with the isolated strain of Pedobacter sp. (previously designated OTU26). The Pedobacter isolate (OTU26) was found to belong to the current OTU_8489 (99.13% sequence identity). This OTU was found to have a relative abundance of 0.26% but was not found to have a significant cultivar or location effect. One other isolate, a suppressive Pseudomonas OTU (previously designated OTU9) was found to share sequence similarity with OTU_13 at a 97.8% identity. OTU_13 was not found to be cultivar-associated, but had an average relative abundance of 0.73%.

Co-occurrence Networks Analysis of Rhizosphere

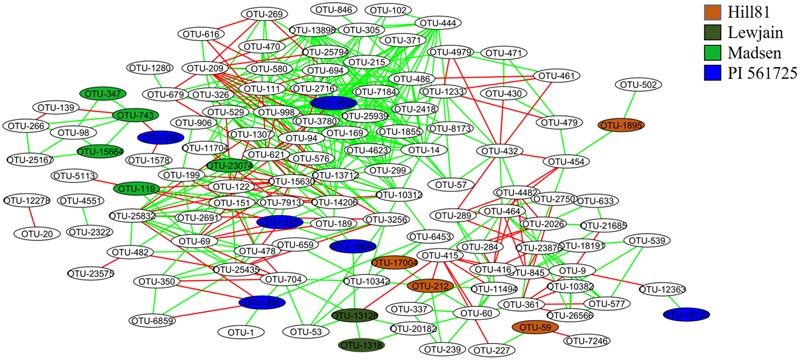

Co-occurrence interactions between bacterial taxa were examined to shed light on which taxa responded at the genera and OTU level to provide a means toward examining the environmental traits causing the variation. When the OTUs were grouped into their respective genera, 204 significant correlations (edges) were identified between 95 nodes (genera). There were strong co-occurrence patterns between members of classes Alphaproteobacteria (genera Methylovirgula and Acidiphilium), Betaproteobacteria (genus Collimonas), Gammaproteobacteria (genus Serratia), Actinobacteria (genus Frankia), and Sphingobacteria (genus Mucilaginibacter). The classes Actinobacteria and Sphingobacteria were found to be most abundant and most interconnected, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). Since not all members of a genus respond similarly, a co-occurrence analysis was performed on individual OTUs using the 148 that showed variation between treatments (cultivar or location). When OTUs that differed by treatment were examined for co-occurrence, 127 OTUs (nodes) out of 148 were involved in 505 co-occurrences (Figure 5). The four OTUs with the greatest positive connectivity were OTU_3780 (26 links, 24 positive), OTU_13898 (25 links, 24 positive), OTU_1832 (24 links, 22 positive), and OTU_998 (24 links, 22 positive). The OTUs 3780, 13898 and 1832 belonged to the genus Sphingamonas and OTU_998 belonged to Segetibacter. OTU_621 and OTU_209, had 14 (21 links) and 12 (16 links) negative correlations and belonged to genera Burkholderia and Rhodoblastus, respectively. OTUs 347, 743 and 15664, all belonging to the genus Gemmatimonas, were shown to co-occur and be most closely associated with cultivar Madsen. A similar association was observed for OTU_13128 and OTU_1318, belonging to genera Mucilaginibacter and Lysobacter, which were most closely associated with Lewjain. In contrast, two OTUs 743 (Gemmatimonas) and 292 (Dyadobacter) were shown to co-exclude and were most closely associated with Madsen and PI561725, respectively. This suggested the host may have factored into their co-exclusion. No correlations were found for seven (OTUs 744, 1134, 1302, 6898, 1748, 11521, 11409) out of the 24 cultivar-associated OTUs in the network analysis (Figure 5). This suggested these OTUs responded more uniquely to the cultivar and location treatments. Relative abundance did not serve a role in the number of co-occurrences and their connectivity (Spearman R = 0.228, P = 0.453).

FIGURE 5.

Co-occurrence networks of the rhizosphere associated bacterial community from different cultivars sampled at two locations. Nodes are labeled by OTU number and are colored by host associated cultivar. The green and red lines specify significant positive and negative correlations (Spearman correlations ≥ 0.8 or ≤-0.8, P < 0.01) between two nodes, respectively.

Predicted Gene Functions for Bacterial Communities by Wheat Cultivars

To characterize members of the rhizosphere community with sequenced metagenomics data, PICRUSt was used to infer 16S rDNA rhizosphere sequences to available sequenced bacterial genomes. These metagenomic interpretations were categorized into known functions associated with sequenced communities using the KEGG database and sequence counts were separated for each wheat cultivar. From the initial analysis, 2552 KEGG orthology (KO) terms were found to be significantly different for wheat cultivars.

Annotations classified into 329 functional KO pathways (level 3). Many of these pathways were not plant associated, so we chose to focus on KEGG pathways or KO functions related to bacterial metabolism that could benefit the plant host, and test the role of the malate root exudates. The pathways chosen were associated with sulfur, nitrogen, malate, phosphorus, and antimicrobial production. From this analysis, 48 KO terms were found to differ for the microbial sequence counts by wheat cultivar. A post hoc analysis demonstrated 12 of these terms were found to have a cultivar effect for both locations (P = 0.02). KO terms for the production of antibiotics streptomycin, tetracycline, and beta-lactam were significantly different for sequence counts by wheat cultivar (Table 4). Wheat cultivar Madsen was found to have the highest number of sequence counts for the antibiotic KO terms, with genera Mucilaginibacter and Pseudomonas contributing 26% of the phenotypic variation. A total of six sulfur associated metabolism terms were found to be significantly different by wheat cultivar. Three terms in the sulfur metabolism pathway, sulfate reductase, sulfate adenyltransferase subunits 1 and 2 were found to have the greatest number of sequence counts for cultivar Madsen. In contrast, PI561725 was found to have the lowest number of sequence counts for these three terms. The genera Mucilaginibacter, Pseudomonas, and Gemmatimonas contributed 33% of the total variation. The wheat cultivars Lewjain and Madsen were found to have the highest numbers of sequence counts associated with nitrogen metabolism. The genera Prevotella and Fusobacterium contributed 41% of the phenotypic variation. Madsen and PI561725 were found to have the highest sequence counts for phosphate metabolism terms inositol oxygenase and inosose dehydrogenase, respectively. The highest number of sequence counts for the malate dehydrogenase enzyme belonged to cultivars PI561722 (N = 72) and PI561725 (N = 255), the two members of the isoline pairs that carried the ALMT1 allele (P = 0.004, Table 4).

Table 4.

Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) 16S rDNA of rarefied functional counts for cultivar associated KEGG KO terms for the wheat rhizosphere soils grown at two farms for two consecutive years.

| Wheat cultivars |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kegg Pathway | Kegg orthology terma | Eltan | Finch | Hill-81 | Lewjain | Madsen | PI561722 | PI561725 | PI561726 | PI516727 | P-value |

| Antimicrobial | Beta lactam production | 41231 | 44570 | 42661 | 39127 | 50088 | 44528 | 35857 | 45102 | 41163 | 0.013 |

| Tetracycline production | 95736 | 99922 | 97660 | 93830 | 106610 | 96432 | 88107 | 101324 | 97863 | 0.019 | |

| Streptomycin production | 43607 | 45411 | 43408 | 41638 | 48939 | 47223 | 40034 | 49039 | 44627 | 0.021 | |

| Sulfur | Cystathionine synthase | 13343 | 13341 | 13396 | 12552 | 15087 | 15589 | 12282 | 15497 | 13258 | 0.002 |

| Metabolism | Sulfate reductase | 17152 | 19529 | 17900 | 17050 | 21289 | 17348 | 14042 | 20219 | 17981 | 0.016 |

| Sulfate adenylyltransferase 1 | 13162 | 13743 | 13244 | 12242 | 15072 | 13709 | 11397 | 14241 | 12945 | 0.006 | |

| Sulfate adenylyltransferase 2 | 20739 | 21001 | 20460 | 19981 | 22507 | 21888 | 19490 | 21668 | 21137 | 0.005 | |

| Nitrogen | Nitric oxide reductase | 4139 | 4112 | 4143 | 4783 | 4349 | 3652 | 4162 | 3736 | 4301 | 0.007 |

| Metabolism | Glutamate synthase | 38235 | 39698 | 39147 | 37301 | 43327 | 41757 | 36778 | 42049 | 40366 | 0.002 |

| Phosphate | Inositol oxygenase | 3746 | 4971 | 4354 | 4089 | 5673 | 3775 | 2476 | 5494 | 4724 | 0.001 |

| Metabolism | Inosose dehydratase | 9264 | 8500 | 8353 | 9518 | 7918 | 10995 | 11270 | 9417 | 9519 | 0.002 |

| Malate | Malate dehydrogenase | 62 | 22 | 27 | 48 | 19 | 78 | 255 | 42 | 58 | 0.004 |

| Metabolism | |||||||||||

aFor each orthology term, the counts are an average of the two sites (three replications per wheat cultivar per site). If there were statistical differences for a cultivar by location, these KO terms were removed from further analysis.

Discussion

The reduction of environmental and financial costs associated with conventional agriculture requires novel management and breeding strategies that aim to shift current high input methods to more sustainable biological methods. Breeding for wheat cultivars that can recruit beneficial microbes could potentially reduce inputs and make production more sustainable. In this work, we characterized the rhizosphere bacteria associated with nine field-grown winter wheat cultivars by comparing the V1–V3 region of the 16S rDNA gene. This method of sampling and analysis allowed for testing host cultivar effects on the rhizosphere bacteria. OTU variation between wheat cultivars was characterized, and 24 out of the1305 most abundant OTU were found to vary in frequency in the rhizospheres of the different wheat cultivars. This result indicated that the host genotype played a minor but significant role in the bacterial diversification of the rhizosphere and that bacterial frequencies can be altered by selecting specific wheat cultivars.

In previous reports, wheat cultivars Lewjain, Eltan, and Hill81 have been shown to differentially select members of the Pseudomonas spp. (Mazzola and Gu, 2002: Gu and Mazzola, 2003; Okubara et al., 2004). Interestingly, no significant differences for Pseudomonas spp. were observable for the same wheat cultivars in the present study. However, members of the Pseudomonas were present in the rhizosphere, accounting for 0.7% of the representative OTUs, and 11 OTUs in the core bacteriome (Figure 1). Mazzola and Gu (2002) demonstrated Lewjain had a tendency to make soils more suppressive to soilborne pathogens like Rhizoctonia spp. and in soils conducive to apple replant disease (Gu and Mazzola, 2003), as compared to other wheat cultivars like Eltan and Madsen. They provided evidence this suppression was mitigated through host-associated recruitment of Pseudomonas spp. into the rhizosphere. Biocontrol studies have often looked at using species like Pseudomonas fluorescence for their production of antimicrobial compound 2,4-diacetylphoroglucinol (2,4-DAPG) (Landa et al., 2003). Interestingly, Landa et al. (2003), observed species of genera Arthrobacter, Chryseobacterium, and Flavobacterium to be enriched in the presence of 2,4-DAPG producing species, such as P. fluorescence. In the present study, we identified OTU_10130 (genus, Arthrobacter), OTU_1302 (Chryseobacterium), and OTU_256 (Flavobacterium) to be enriched in the rhizosphere of some wheat lines, especially line PI561725. Although, in significantly lower abundance than PI561725, OTU_1302 was observed to be in greater abundance for the wheat cultivar Lewjain than for other cultivars. However, we did not see the same higher relative abundance for OTUs 256 and 10130. It is likely that the different soil types and their microbial communities, or the methods employed in the previous studies, such as using a greenhouse or growth chamber, may have attributed to differences in these studies.

Differences in the rhizosphere communities of various crop species have been observed (Aira et al., 2010; Bouffaud et al., 2012; Peiffer et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2015), including differences with two wheat cultivars using TRFLP on the V1–V3 region (Donn et al., 2015). Interestingly, our results differed from a recent report by Corneo et al. (2016) on 24 wheat lines which found no microbial community differences at the vegetative stages of wheat using the TRFLP method on amplicons generated from the V3–V6 hypervariable regions. The lower resolution by the TRFLP method may have affected their ability to identify community differences between wheat lines. In this study, as well as the work by Donn et al. (2015), rhizosphere samples were collected at the reproductive stages and examined after 2 years of growth in the same soil. In previous studies, no differences were found in the first planting cycle (Donn et al., 2015), or in the vegetative stages (Donn et al., 2015; Corneo et al., 2016) of wheat. Several lines of evidence suggest bacteria are recruited through root exudates, and the greatest release may occur during the reproductive stages (Steinkellner et al., 2007; Rudrappa et al., 2008b; Ferluga and Venturi, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Neal et al., 2012; Lakshmanan et al., 2013). Multiple growth cycles of different wheat genotypes to recruit responsive microbes may be necessary to see noticeable changes in their frequencies, depending on their initial frequencies in the soil. Changes of frequencies in bulk soil, not just soil closely associated with wheat roots, would presumably take longer but wheat genotypes with stronger effects on microbial communities may be able to affect these communities more rapidly.

Plants have evolved mechanisms to tolerate the toxic effects of aluminum by excreting organic acids into rhizosphere soils (Kochian et al., 2004). In wheat, the gene TaALMT1, an Al-activated malate transporter has been found to confer such a tolerance (Sasaki et al., 2004). A previous study involving an aluminum tolerant (Atlas 66) and intolerant line (Scout 66) found no significant differences after 60 days for the rhizosphere communities using DGGE methods (Wang et al., 2013). We compared two sets of isolines and found very noticeable differences in the Century background (PI561725 and PI561727) but not in the Chisholm background (PI561722 and PI561726; Figure 3; Table 3). Differences in the genetic background of these pairs could have attributed to the observable changes through a differential response to aluminum or an induced root defense response (Rudrappa et al., 2008a; Millet et al., 2010). Lakshmanan et al. (2012) reported the bacterial MAMP flg22 or the phytotoxin coronatine can induce malic acid expression in Arabidopsis thaliana in the absence of a low pH or an aluminum rich environment. Additional experiments with the ALMT1 isolines are warranted to determine how the gene expression is regulated in response to environmental stimulus and if other factors that differ between the two genetic backgrounds affect malate secretion.

Previous evidence has found that wheat and other plant species differ in the organic compounds they deposit into the soil rhizosphere (Rengel and Römheld, 2000; Sasaki et al., 2004; Zuo et al., 2014). Multiple biochemical differences were found between the bacterial communities associated with roots of different wheat lines as indicated by KO functions and pathways (Table 4). Zuo et al. (2014) found an increase in nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying bacteria, as well as microbial enzymes associated with nitrogen and carbon metabolism in response to different wheat lines (e.g., ‘22 Xiaoyan’). It was suggested that differences in root phytochemicals could have attributed to the observable differences. In A. thaliana, induction of the AtALMT1 gene, and subsequently the increase in root exudates of MA, had the effect of recruiting bacterial species Bacillus subtilis (strain FB17) into the rhizosphere (Lakshmanan et al., 2013). In the present study, wheat cultivar differences in the bacterial sequence counts by KO terms could be the result of root exudates which select and increase bacteria associated with antibiotic production, sulfur, nitrogen, phosphorus, and malate responsive metabolisms (Table 4).

Some of the wheat cultivar-associated bacteria identified in this study may provide beneficial services to their host. Different strains of bacteria isolated from soil have been found to promote plant growth by producing plant hormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (auxin) and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate, a precursor for ethylene (Maimaiti et al., 2007; Madhaiyan et al., 2010; Marques et al., 2010; Soltani et al., 2010). It is theorized that the increase in plant growth creates a positive feedback which increases root exudates for bacterial metabolism. Two genera in this study Amycolatopsis and Sphingomonas were found to be wheat cultivar-associated and members of these genera have been previously shown to contribute to plant health by antibiotic production (Wink et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2016) and disease suppressive effects (Vogel et al., 2012), respectively. There is further evidence to suggest that strains of Chryseobacterium and Pedobacter produce antifungal compounds against soilborne Phytophthora and Rhizoctonia species (Marques et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2013), although, the mechanism for this suppression is still unclear. In this study, the OTU_1302 corresponded to a C. soldanellicola isolate which was identified by Yin et al. (2013) and found to suppress R. solani in culture and in greenhouse assays. Several other suppressive bacteria were identified in that study but did not correspond to any of our wheat cultivar associated OTUs. These results indicated that disease suppressive soils, although not tested in our study, may be attributed to multiple species working in concert together (Mendes et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2015; Chapelle et al., 2016).

Sequencing depth played a major role in quantifying the bacterial community. Altogether, 26,604 OTUs with a ≥97% sequence similarity were found. These numbers are higher than reported in previous wheat rhizosphere studies using pyrosequencing and TRFLP (Donn et al., 2015; Corneo et al., 2016) and are consistent with other rhizosphere sequencing studies (Mendes et al., 2011; Peiffer et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2015). Increasing sequencing depth would allow for rarer OTUs to be sequenced which may provide improved cataloging of unclassifiable or unculturable OTUs. When OTUs were filtered by a relative abundance of 0.01%, 1305 remained, suggesting a large portion of the community is composed of rarer OTUs. A recent study suggests that the roots of wild grasses such as oat (Avena spp.) select for rarer bacterial communities, and despite deeper 16S rDNA sequencing, these rarer bacteria were not detectable in the bulk soil (Nuccio et al., 2016). Our data is consistent with these findings and suggested a large portion of OTUs were not in high abundance but were detectable using deeper 16S rDNA sequencing.

The most dominant taxa observed in our wheat rhizospheres were in agreement with previous wheat studies but differ from those of other species. The most abundant families in the present study were Sphingobacteriaceae (Bacteroidetes; 15.5% of total sequence reads) and Gemmatimonadaceae. Previous studies complement the current study demonstrating Sphingobacteriaceae as a dominant taxon in the wheat rhizosphere (Yin et al., 2010, 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Donn et al., 2015; Corneo et al., 2016). Alternatively, the most dominant taxa for Arabidopsis (Bulgarelli et al., 2012; Lundberg et al., 2012) and Lettuce (Cardinale et al., 2015) was Comamonadaceae (Proteobacteria), which accounted for only 0.01% of the total sequence reads for the present study. In studies comparing wild and domesticated maize, the family Burkholderiaceae has been found to be the most dominant (Estrada et al., 2002; Szoboszlay et al., 2015). Other abundant taxa, such as Bradyrhizobiaceae and Sphingomonadaceae have also been found in the rhizospheres of wheat, Arabidopsis, lettuce, and sugarcane (Bulgarelli et al., 2012; Lundberg et al., 2012; Yeoh et al., 2015) and are apparently less species dependent. However, it is difficult to determine how the representative OTUs in the present study compare with other studies due to the differences in sequenced regions, platforms, and the techniques used.

We have shown wheat cultivars are involved in shaping the rhizosphere by differentially altering the bacterial community. Using deep 16S rDNA sequencing, we could characterize a larger portion of the rhizosphere community than has been previously reported. The differences in microbial communities observed on different wheat lines indicate that rhizosphere communities can be manipulated by wheat breeding. The specific community members found to be responsive to different wheat lines can be used as biomarkers for these community-altering traits. These biomarkers will assist in dissecting the genetic pathways used by these wheat hosts in recruitment, and provide the necessary tools for breeders to incorporate these favorable alleles into commercial production. A future challenge will be to determine which of these traits, and which recruited microbial community components, provide advantages to sustainable wheat production in various environments.

Author Contributions

SH conceived the research project with input from AM and CY on technical aspects. AM and CY collected the samples, generated the amplicons and processed the sequences. AM performed the data analysis. AM and SH wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to the manuscript revision.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Washington State University Graduate School Global Plant Sciences Initiative and the Washington Grain Commission. PPNS number 0717, Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, Human and Natural Resource Sciences, Agricultural Research Center, Washington State University. We thank Ron Sloot and Josh Demacon for their technical support in the management of the field plots.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00132/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aira M., Gómez-Brandón M., Lazcano C., Baath E., Domínguez J. (2010). Plant genotype strongly modifies the structure and growth of maize rhizosphere microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 2276–2281. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.08.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese D., Fontana P., De Filippo C., Cavalieri D., Donati C. (2015). MICCA: a complete and accurate software for taxonomic profiling of metagenomic data. Sci. Rep. 5:9743 10.1038/srep09743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badri D. V., Chaparro J. M., Zhang R., Shen Q., Vivanco J. M. (2013). Application of natural blends of phytochemicals derived from the root exudates of Arabidopsis to the soil reveal that phenolic-related compounds predominantly modulate the soil microbiome. J. Biol. Chem. 288 4502–4512. 10.1074/jbc.M112.433300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bais H. P., Weir T. L., Perry L. G., Gilroy S., Vivanco J. M. (2006). The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 233–266. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y., de-Bashan L. E., Prabhu S. R., Hernandez J.-P. (2014). Advances in plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculant technology: formulations and practical perspectives (1998–2013). Plant Soil 378 1–33. 10.1007/s11104-013-1956-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg G., Smalla K. (2009). Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68 1–13. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffaud M.-L., Kyselková M., Gouesnard B., Grundmann G., Muller D., Moenne-Loccoz Y. (2012). Is diversification history of maize influencing selection of soil bacteria by roots? Mol. Ecol. 21 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarelli D., Garrido-Oter R., Münch P. C., Weiman A., Dröge J., Pan Y., et al. (2015). Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe 17 392–403. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarelli D., Rott M., Schlaeppi K., van Themaat E. V. L., Ahmadinejad N., Assenza F., et al. (2012). Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488 91–95. 10.1038/nature11336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7 335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale M., Grube M., Erlacher A., Quehenberger J., Berg G. (2015). Bacterial networks and co-occurrence relationships in the lettuce root microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 17 239–252. 10.1111/1462-2920.12686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhais L. C., Dennis P. G., Badri D. V., Kidd B. N., Vivanco J. M., Schenk P. M. (2015). Linking jasmonic acid signaling, root exudates, and rhizosphere microbiomes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28 1049–1058. 10.1094/MPMI-01-15-0016-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhais L. C., Dennis P. G., Badri D. V., Tyson G. W., Vivanco J. M., Schenk P. M. (2013). Activation of the jasmonic acid plant defence pathway alters the composition of rhizosphere bacterial communities. PLoS ONE 8:e56457 10.1371/journal.pone.0056457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni P., Warner D., Bensen R. J., Anstrom D. C., Harrison J., Stoecker M., et al. (2008). Bacterial RNA chaperones confer abiotic stress tolerance in plants and improved grain yield in maize under water-limited conditions. Plant Physiol. 147 446–455. 10.1104/pp.108.118828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J.-Y., Han S., Hong H.-J., Cho H., Kim D., Kwon Y., et al. (2015). Microbial and biochemical basis of a Fusarium wilt-suppressive soil. ISME J. 10 119–129. 10.1038/ismej.2015.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle E., Mendes R., Bakker P. A. H., Raaijmakers J. M. (2016). Fungal invasion of the rhizosphere microbiome. ISME J. 10 265–268. 10.1038/ismej.2015.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Wu Q., Shen Q., Wang H. (2016). Progress in understanding the genetic information and biosynthetic pathways behind Amycolatopsis antibiotics, with implications for the continued discovery of novel drugs. ChemBioChem 17 119–128. 10.1002/cbic.201500542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Wang Q., Cardenas E., Fish J., Chai B., Farris R. J., et al. (2009). The ribosomal database project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D141–D145. 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneo P. E., Suenaga H., Kertesz M. A., Dijkstra F. A. (2016). Effect of twenty four wheat genotypes on soil biochemical and microbial properties. Plant Soil 404 1–15. 10.1007/s11104-016-2833-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer W., Hundscheid M. P., Gunnewiek P. J. K., de Ridder-Duine A. S., Thion C., Van Veen J. A., et al. (2015). Antifungal rhizosphere bacteria can increase as response to the presence of saprotrophic fungi. PLoS ONE 10:e0137988 10.1371/journal.pone.0137988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donn S., Kirkegaard J. A., Perera G., Richardson A. E., Watt M. (2015). Evolution of bacterial communities in the wheat crop rhizosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 17 610–621. 10.1111/1462-2920.12452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10 996–998. 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J., Johnson C., Santos-Medellín C., Lurie E., Podishetty N. K., Bhatnagar S., et al. (2015). Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 E911–E920. 10.1073/pnas.1414592112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada P., Mavingui P., Cournoyer B., Fontaine F., Balandreau J., Caballero-Mellado J. (2002). A N2-fixing endophytic Burkholderia sp. associated with maize plants cultivated in Mexico. Can. J. Microbiol. 48 285–294. 10.1139/w02-023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust K., Sathirapongsasuti J. F., Izard J., Segata N., Gevers D., Raes J., et al. (2012). Microbial co-occurrence relationships in the human microbiome. PLoS Comput Biol. 8:e1002606 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2015). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook, 2015–2024. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ferluga S., Venturi V. (2009). OryR is a LuxR-family protein involved in interkingdom signaling between pathogenic Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and rice. J. Bacteriol. 191 890–897. 10.1128/JB.01507-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick B. R. (2014). Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 169 30–39. 10.1016/j.micres.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.-H., Mazzola M. (2003). Modification of fluorescent pseudomonad community and control of apple replant disease induced in a wheat cultivar-specific manner. Appl. Soil Ecol. 24 57–72. 10.1016/S0929-1393(03)00066-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q.-Q., Lü X.-P., Bai J.-P., Qiao Y., Paré P. W., Wang S.-M., et al. (2014). Beneficial soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis (GB03) augments salt tolerance of white clover. Front. Plant Sci. 5:525 10.3389/fpls.2014.00525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasim W. A., Osman M. E., Omar M. N., El-Daim I. A. A., Bejai S., Meijer J. (2013). Control of drought stress in wheat using plant-growth-promoting bacteria. J. Plant Growth Regulation 32 122–130. 10.1007/s12088-014-0479-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-S., Sang M. K., Jung H. W., Jeun Y.-C., Myung I.-S., Kim K. D. (2012). Identification and characterization of Chryseobacterium wanjuense strain KJ9C8 as a biocontrol agent of Phytophthora blight of pepper. Crop Protection 32 129–137. 10.1016/j.cropro.2011.10.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochian L. V., Hoekenga O. A., Pineros M. A. (2004). How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 459–493. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebbing S. E., Classen A. T., Call J. J., Henning J. A., Simberloff D. (2015). Plant–soil interactions promote co-occurrence of three nonnative woody shrubs. Ecology 96 2289–2299. 10.1890/14-2006.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P. S., Brooker M. R., Dowd S. E., Camerlengo T. (2011). Target region selection is a critical determinant of community fingerprints generated by 16S pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 6:e20956 10.1371/journal.pone.0020956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan V., Castaneda R., Rudrappa T., Bais H. P. (2013). Root transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to beneficial Bacillus subtilis FB17 rhizobacteria revealed genes for bacterial recruitment and plant defense independent of malate efflux. Planta 238 657–668. 10.1007/s00425-013-1920-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan V., Kitto S. L., Caplan J. L., Hsueh Y.-H., Kearns D. B., Wu Y.-S., et al. (2012). Microbe-associated molecular patterns-triggered root responses mediate beneficial rhizobacterial recruitment in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 160 1642–1661. 10.1104/pp.112.200386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa B. B., Mavrodi D. M., Thomashow L. S., Weller D. M. (2003). Interactions between strains of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in the rhizosphere of wheat. Phytopathology 93 982–994. 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.8.982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille M. G., Zaneveld J., Caporaso J. G., McDonald D., Knights D., Reyes J. A., et al. (2013). Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 814–821. 10.1038/nbt.2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg D. S., Lebeis S. L., Paredes S. H., Yourstone S., Gehring J., Malfatti S., et al. (2012). Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 488 86–90. 10.1038/nature11237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhaiyan M., Poonguzhali S., Lee J.-S., Senthilkumar M., Lee K. C., Sundaram S. (2010). Mucilaginibacter gossypii sp. nov. and Mucilaginibacter gossypiicola sp. nov., plant-growth-promoting bacteria isolated from cotton rhizosphere soils. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60 2451–2457. 10.1099/ijs.0.018713-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimaiti J., Zhang Y., Yang J., Cen Y.-P., Layzell D. B., Peoples M., et al. (2007). Isolation and characterization of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria induced following exposure of soil to hydrogen gas and their impact on plant growth. Environ. Microbiol. 9 435–444. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques A. P., Pires C., Moreira H., Rangel A. O., Castro P. M. (2010). Assessment of the plant growth promotion abilities of six bacterial isolates using Zea mays as indicator plant. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 1229–1235. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.04.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola M., Gu Y.-H. (2002). Wheat genotype-specific induction of soil microbial communities suppressive to disease incited by Rhizoctonia solani anastomosis group (AG)-5 and AG-8. Phytopathology 92 1300–1307. 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.12.1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R., Kruijt M., de Bruijn I., Dekkers E., van der Voort M., Schneider J. H., et al. (2011). Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science 332 1097–1100. 10.1126/science.1203980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet Y. A., Danna C. H., Clay N. K., Songnuan W., Simon M. D., Werck-Reichhart D., et al. (2010). Innate immune responses activated in Arabidopsis roots by microbe-associated molecular patterns. Plant Cell 22 973–990. 10.1105/tpc.109.069658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D. B., Vogel C., Bai Y., Vorholt J. A. (2016). The plant microbiota: systems biology insights and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Genet. 50 211–234. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-034952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Noya Y. E., Gómez-Acata S., Montoya-Ciriaco N., Rojas-Valdez A., Suárez-Arriaga M. C., Valenzuela-Encinas C., et al. (2013). Relative impacts of tillage, residue management and crop-rotation on soil bacterial communities in a semi-arid agroecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 65 86–95. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M., Hussain M. B., Zahir Z. A., Mitter B., Sessitsch A. (2014). Drought stress amelioration in wheat through inoculation with Burkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN. Plant Growth Regulation 73 121–131. 10.1007/s10725-013-9874-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal A. L., Ahmad S., Gordon-Weeks R., Ton J. (2012). Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 7:e35498 10.1371/journal.pone.0035498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuccio E. E., Anderson-Furgeson J., Estera K. Y., Pett-Ridge J., Valpine P., Brodie E. L., et al. (2016). Climate and edaphic controllers influence rhizosphere community assembly for a wild annual grass. Ecology 97 307–1318. 10.1890/15-0882.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubara P. A., Kornoely J. P., Landa B. B. (2004). Rhizosphere colonization of hexaploid wheat by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains Q8r1-96 and Q2-87 is cultivar-variable and associated with changes in gross root morphology. Biol. Control 30 392–403. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2003.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D. H., Beiko R. G. (2010). Identifying biologically relevant differences between metagenomic communities. Bioinformatics 26 715–721. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer J. A., Spor A., Koren O., Jin Z., Tringe S. G., Dangl J. L., et al. (2013). Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 6548–6553. 10.1073/pnas.1302837110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo I., Ledger T., Greve M., Poupin M. J. (2015). Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN induces long-term metabolic and transcriptional changes involved in Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 6:466 10.3389/fpls.2015.00466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plociniczak T., Sinkkonen A., Romantschuk M., Sułowicz S., Piotrowska-Seget Z. (2016). Rhizospheric bacterial strain brevibacterium casei MH8a colonizes plant tissues and enhances Cd, Zn, Cu phytoextraction by white mustard. Front. Plant Sci. 7:101 10.3389/fpls.2016.00101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers J. M., Mazzola M. (2016). Soil immune responses. Science 352 1392–1393. 10.1126/science.aaf3252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengel Z., Römheld V. (2000). Root exudation and Fe uptake and transport in wheat genotypes differing in tolerance to Zn deficiency. Plant Soil 222 25–34. 10.1023/A:1004799027861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrappa T., Czymmek K. J., Paré P. W., Bais H. P. (2008a). Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 148 1547–1556. 10.1104/pp.108.127613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrappa T., Splaine R. E., Biedrzycki M. L., Bais H. P. (2008b). Cyanogenic pseudomonads influence multitrophic interactions in the rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 3:e2073 10.1371/journal.pone.0002073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M., Law A. D., Moe L. A. (2016). Nicotiana roots recruit rare rhizosphere taxa as major root-inhabiting microbes. Microb. Ecol. 71 469–472. 10.1007/s00248-015-0672-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma R. K., Saikia R. (2014). Alleviation of drought stress in mung bean by strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGRJ21. Plant Soil 377 111–126. 10.1007/s11104-013-1981-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Yamamoto Y., Ezaki B., Katsuhara M., Ahn S. J., Ryan P. R., et al. (2004). A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 37 645–653. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessitsch A., Kuffner M., Kidd P., Vangronsveld J., Wenzel W. W., Fallmann K., et al. (2013). The role of plant-associated bacteria in the mobilization and phytoextraction of trace elements in contaminated soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 60 182–194. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Ruan Y., Xue C., Zhong S., Li R., Shen Q. (2015). Soils naturally suppressive to banana Fusarium wilt disease harbor unique bacterial communities. Plant Soil 393 21–33. 10.1007/s11104-015-2474-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani A.-A., Khavazi K., Asadi-Rahmani H., Omidvari M., Dahaji P. A., Mirhoseyni H. (2010). Plant growth promoting characteristics in some Flavobacterium spp. isolated from soils of Iran. J. Agric. Sci. 2:106 10.5539/jas.v2n4p106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkellner S., Lendzemo V., Langer I., Schweiger P., Khaosaad T., Toussaint J.-P., et al. (2007). Flavonoids and strigolactones in root exudates as signals in symbiotic and pathogenic plant-fungus interactions. Molecules 12 1290–1306. 10.3390/12071290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szoboszlay M., Lambers J., Chappell J., Kupper J. V., Moe L. A., McNear D. H. (2015). Comparison of root system architecture and rhizosphere microbial communities of Balsas teosinte and domesticated corn cultivars. Soil Biol. Biochem. 80 34–44. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tkacz A., Cheema J., Chandra G., Grant A., Poole P. S. (2015). Stability and succession of the rhizosphere microbiota depends upon plant type and soil composition. ISME J. 9 2349–2359. 10.1038/ismej.2015.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe S. G., Von Mering C., Kobayashi A., Salamov A. A., Chen K., Chang H. W., et al. (2005). Comparative metagenomics of microbial communities. Science 308 554–557. 10.1126/science.1107851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Q., Zhou X., He Z., Xue K., Wu L., Reich P., et al. (2016). The diversity and co-occurrence patterns of N2-fixing communities in a CO2-enriched grassland ecosystem. Microb. Ecol. 71 604–615. 10.1007/s00248-015-0659-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam N. M., Bouwmeester H. J. (2016). Metabolomics in the rhizosphere: tapping into belowground chemical communication. Trends Plant Sci. 21 256–265. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangronsveld J., Herzig R., Weyens N., Boulet J., Adriaensen K., Ruttens A., et al. (2009). Phytoremediation of contaminated soils and groundwater: lessons from the field. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 16 765–794. 10.1007/s11356-009-0213-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C., Innerebner G., Zingg J., Guder J., Vorholt J. A. (2012). Forward genetic in planta screen for identification of plant-protective traits of Sphingomonas sp. strain Fr1 against Pseudomonas syringae DC3000. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 5529–5535. 10.1128/AEM.00639-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhao X. Q., Chen R. F., Chu H. Y., Shen R. F. (2013). Aluminum tolerance of wheat does not induce changes in dominant bacterial community composition or abundance in an acidic soil. Plant Soil 367 275–284. 10.1007/s11104-012-1473-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller D. M., Raaijmakers J. M., Gardener B. B. M., Thomashow L. S. (2002). Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens 1. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40 309–348. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.030402.110010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink J. M., Kroppenstedt R. M., Ganguli B. N., Nadkarni S. R., Schumann P., Seibert G., et al. (2003). Three new antibiotic producing species of the genus Amycolatopsis, Amycolatopsis balhimycina sp. nov., A. tolypomycina sp. nov., A. vancoresmycina sp. nov., and description of Amycolatopsis keratiniphila subsp. keratiniphila subsp. nov. and A. keratiniphila subsp. nogabecina subsp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissuwa M., Mazzola M., Picard C. (2009). Novel approaches in plant breeding for rhizosphere-related traits. Plant Soil 321 409–430. 10.1007/s11104-008-9693-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh Y. K., Paungfoo-Lonhienne C., Dennis P. G., Robinson N., Ragan M. A., Schmidt S., et al. (2015). The core root microbiome of sugarcanes cultivated under varying nitrogen fertilizer application. Environ. Microbiol. 18 1338–1351. 10.1111/1462-2920.12925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Hulbert S. H., Schroeder K. L., Mavrodi O., Mavrodi D., Dhingra A., et al. (2013). Role of bacterial communities in the natural suppression of Rhizoctonia solani bare patch disease of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 7428–7438. 10.1128/AEM.01610-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Jones K. L., Peterson D. E., Garrett K. A., Hulbert S. H., Paulitz T. C. (2010). Members of soil bacterial communities sensitive to tillage and crop rotation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 2111–2118. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Morrison M. (2004). Comparisons of different hypervariable regions of rrs genes for use in fingerprinting of microbial communities by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 4800–4806. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4800-4806.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachow C., Müller H., Tilcher R., Berg G. (2014). Differences between the rhizosphere microbiome of Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima—ancestor of all beet crops—and modern sugar beets. Front. Microbiol. 5:415 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Subramanian S., Stacey G., Yu O. (2009). Flavones and flavonols play distinct critical roles during nodulation of Medicago truncatula by Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant J. 57 171–183. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo S., Li X., Ma Y., Yang S. (2014). Soil microbes are linked to the allelopathic potential of different wheat genotypes. Plant Soil 378 49–58. 10.1007/s11104-013-2020-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.