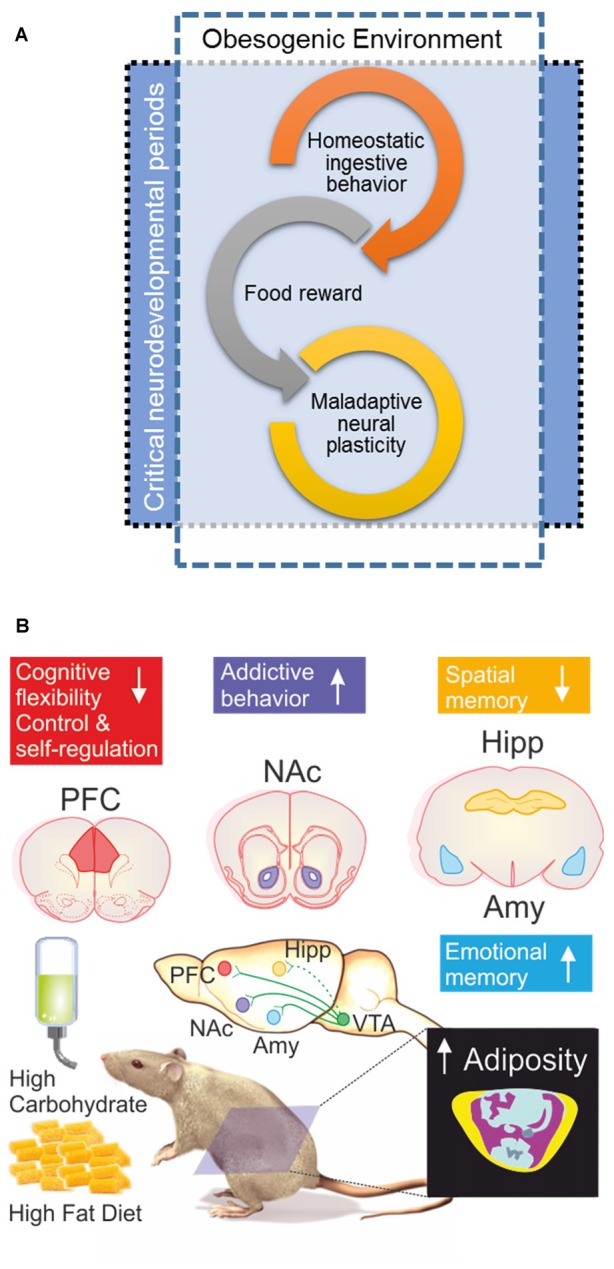

Figure 2.

(A) When the obesogenic environment overlaps critical neurodevelopmental periods, enhanced maladaptive neural plasticity may be expected; which could eventually lead to uncontrolled ingestive behavior (food addiction). Interplay of food reward and homeostatic ingestive behavior may evolve in wilderness to promote biological fitness under extremely different evolutionary pressures; e.g., scarcity and unpredictable access to food, low dense caloric food, large caloric investments in foraging/hunting. (B) Obesogenic environment driven by palatable hyper-caloric (PHc) food can be experimentally modeled in rodents by exposure to high carbohydrate/high fat diet (HFD) resulting in increased adiposity evidenced by body composition analysis by micro-computed tomography; yellow = sub cutaneous fat/pink = visceral fat, blue = lean mass, ultimately causing diet induced obesity (DIO). Experimental evidence documents that exposure to a high carbohydrate/HFD negatively impact on cognitive functions, with increased sensitivity during prenatal, childhood and adolescence neurodevelopmental stages. In particular, hippocampal (Hipp) and pre-frontal cortex (PFC) dependent tasks are negatively impaired; whereas amygdala (Amy) dependent function seems to be enhanced. Cognitive impairments are accompanied (or preceded) by ingestive addictive behaviors driven by the dopaminergic reward system that initiates its projections on the ventral tegmental area (VTA) directly innervating the Amy, PFC, as well as the nucleus accumbens (NAcc; Lisman and Grace, 2005; Russo and Nestler, 2013), the brain structure assessing the hedonic and saliency stimuli properties. It should be remarked that direct projections from VTA to Hipp are on current debate (Takeuchi et al., 2016), thus are depicted with a dash-line. The “reward deficiency syndrome” propose that addiction vulnerability results on from hyporesponsiveness of the midbrain dopaminergic system, leading individuals to seek out and engage in addictive behaviors in order to compensate for underarousal (George et al., 2012), which is in line to the theory of food addiction (Volkow and Wise, 2005; Davis et al., 2011) in particular for PHc food (Ifland et al., 2009; Schulte et al., 2015).