Abstract

Objectives

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Geriatric Emergency Department (ED) guidelines and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that older adults be assessed for risk of falls. The standard ED assessment is a verbal query of fall risk factors, which may be inadequate. We hypothesized that the addition of a functional balance test endorsed by the CDC STEADI falls prevention guidelines, the 4 Stage Balance Test (4SBT), would improve the detection of patients at risk for falls.

Methods

Prospective pilot study of a convenience sample of ambulatory adults ≥65 years old in the ED. All participants received the standard nursing triage fall risk assessment. After patients were stabilized in their ED room, the 4SBT was administered.

Results

The 58 participants had an average age of 74.1 years (range 65–94), 40.0% were women, and 98% were community dwelling. Five (8.6%) presented to the ED for a fall-related chief complaint. The nursing triage screen identified 39.7% (n=23) as at risk for falls, while the 4SBT identified 43% (n=25). Combining triage questions with the 4SBT identified 60.3% (n=35) as high risk for falls as compared to 39.7% (n=23) with triage questions alone (p<0.01). Ten (17%) of the patients at high risk by 4SBT and missed by triage questions were in patients unaware that they were at risk for falls (new diagnoses).

Conclusions

Incorporating a quick functional test of balance into the ED assessment for fall risk is feasible, and significantly increases the detection of older adults at risk for falls.

Keywords: Fall risk, Emergency Department, Triage, CDC guidelines

Introduction

Despite the high burden of injury from falls and an emphasis on fall prevention for patients in the hospital, the current Emergency Department (ED) practices of falls screening and management is inadequate.1 The ED setting is an ideal healthcare site to focus on fall prevention, as US EDs care for 2.6 million older adults for falls a year.2 Additionally, 31% will fall again within 6 months of their ED visit.3

We wished to implement sustainable fall risk detection and fall prevention from the ED. The first step in this process, as recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is to choose a fall risk assessment. The current fall risk assessment in most EDs is a quick verbal query by the triage nursing staff (Table 1). This consists of 2 questions about previously validated risk factors for future falls- recent falls and use of a cane or walker- and a nursing assessment of altered mental status. However, it is unclear if this is sufficient to identify all, or even most, patients at risk for falls. Self-report or verbal query alone is likely insufficient to risk stratify patients. A meta-analysis of questionnaire tools to predict fall risk after the ED visit found that all were inadequate.3 This may be because older adults often misrepresent or underestimate their own fall risk, or may be due to the distractions of acute illness and the ED setting. A functional, quantitative fall risk assessment is needed.

Table 1.

Wording of the triage assessment questions. Triage nurses in the ED ask these questions of all patients as part of a standard fall risk assessment, similar to most institutions in the USA.

| Have you fallen in the past month? |

| Do you use a walker, cane or other assistive device to help you walk? |

| (Nurse Assessment) Are there signs of altered mental status? |

While there is no gold standard for fall risk stratification, the CDC STEADI Fall Prevention Guidelines recommend combining a verbal query with a functional assessment.4 The majority of functional gait and balance tests were developed in non-ED settings without the time, space, and equipment limitations of the ED (see Table 2). Functional assessments of gait and balance are difficult to incorporate into routine care in the ED setting, as even simple equipment such as a chair without wheels or arms may be unavailable. Gait assessments such as the Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT) necessitate removing patients from necessary cardiac monitors and are nursing intensive. Prior studies of administration of the TUGT in the ED have required a trained geriatric nurse liaison or research staff. In a normal busy ED setting, the TUGT is overly burdensome.

Table 2.

Possible standardized gait and balance tests evaluated for ED use, abstracted from a recent review.10

| Test: | Equipment: | Time to perform: |

|---|---|---|

| Timed up and Go | Chair without wheels and a 3 meter straight path |

5 minutes |

| Sit to stand test | Chair without arms or wheels | 30 seconds |

| 10-Meter walking test | 10 meter path to walk | <1 minute |

| Berg Balance Scale | Yardstick, 2 standard chairs (one with arm rests, one without), Footstool or step, Stopwatch or wristwatch, 15 ft walkway |

15–20 minutes |

| Step test | 7.5cm step, step up and down quickly |

10 minutes |

| 4 Stage Balance Test (FICSIT- 4) |

None | 40 seconds |

The CDC STEADI guidelines recommend two alternatives to the TUGT- the Sit to Stand test and the 4 Stage Balance Test (4SBT).4 The 4SBT can be done at the bedside with monitors attached, and as an additional benefit orthostatic vital signs can be obtained simultaneously (Figure 1).5 The 4SBT is limited in that it evaluates static balance only, not gait. However, prior research suggests that a simple static balance test has similar fall risk prediction validity as more complicated balance and gait tests, and in the ED setting stance testing can identify recurrent fallers as well as the TUGT.6

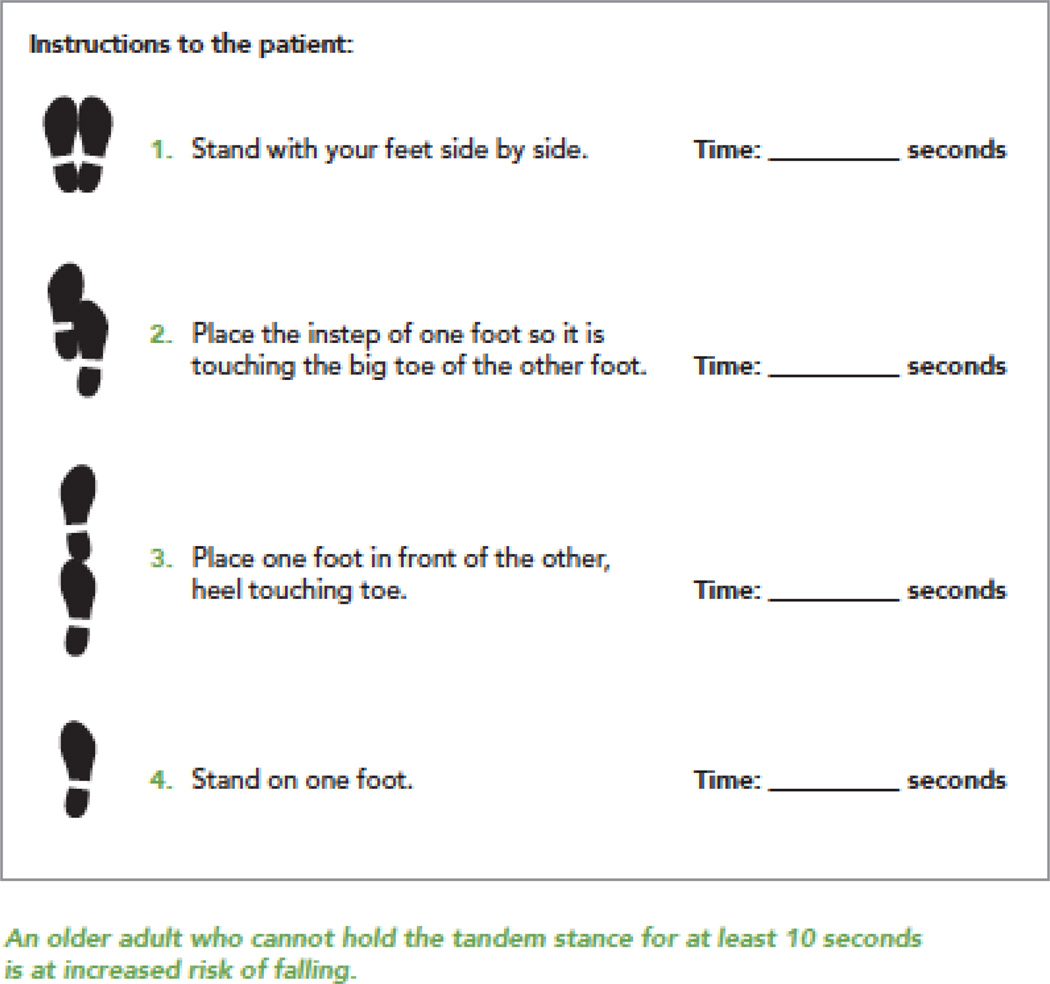

Figure 1.

The 4 Stage Balance Test, reproduced from the CDC STEADI guidelines with permission.4 The 4 Stage Balance Test requires a patient to stand in four progressively harder stances for 10 seconds each. The test is terminated early and patient is considered at risk for falls if the patient cannot hold a stance for 10 seconds. The patient is at low fall risk of they can hold the tandem stance for 10 seconds.

We hypothesized that following the CDC recommendations and incorporating a validated balance assessment into the ED evaluation would detect a higher number of patients at risk for falls.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

Institutional IRB-approved prospective cohort study of ambulatory older adult ED patients. Our ED is a 106 bed unit in a tertiary care hospital with over 76,000 ED visits a year, 13% of which are older adults.

Selection of Participants

Nursing staff were approached to assist in identifying ED patients ≥65 years old who were able to stand unassisted for greater than 1 minute and able to follow simple directions. Exclusion criteria included acute lower extremity pain limiting weight bearing, orders for bedrest, non-English speaking, and unable to follow simple commands.

Intervention

Use of the 4SBT for fall risk stratification in older adults in the ED.

Methods and Measurements

Of the adults ≥65 years old in the ED during study recruitment hours, 43% did not meet criteria and 30% were unavailable (out of the room for testing or discharged prior to contact for the study). Of those approached, 43% participated (n=63). Basic demographic information was collected. The results of the nursing triage screen for falls risk was noted. A “yes” response to any of the questions meant that the person was a fall risk (Table 1). The patient’s ED nurse and the research staff administered the 4SBT together. Patients were also asked about their own self-perception and prior diagnosis of fall risk. Every patient received an educational handout on fall prevention. If the patient was at risk for falls based upon the results of the 4SBT (i.e., unable to hold tandem stance for 10 seconds), the patient’s physician team was informed. All patients at risk were referred to our institution’s Fall Prevention Clinic, an outpatient clinic run by physiatrists and physical therapists that performs multimodal evaluations for fall risk factors and arranges treatment.

Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the author’s institution. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.7 Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) was used to calculate means and proportions as indicated. Fisher’s Exact test was used to compare the probabilities of identifying a person as being at fall risk using triage screening alone versus the triage screen with the addition of the 4SBT.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

Sixty three patients were recruited for the study. Two did not receive triage fall screens and so were excluded from the final analysis. Three patients were excluded due to inability to attempt the 4 Stage Balance test, one due to pain and two due to nursing availability. This resulted in 58 patients for the final analysis. Average age was 74.1 years (range 65–94), 40.0% were women, and almost all were community dwelling (98.3%). The majority lived with family, with only 27.6% (n=16) living alone. Five (8.6%) were in the ED for a fall related chief complaint. The other patients presented for a variety of complaints, most commonly shortness of breath or cough.

Main results

The nursing triage screen identified 39.7% (n=23) of patients as at risk for falls, and over half of these patients also were high risk by the 4SBT (56.5%, n=13). Of those who were screened as no fall risk, 34% (n=12) failed their 4SBT. The 4SBT alone identified 43% (n=25) as at high risk for falls. Combining triage questions with the 4SBT identified 60.3% (n=35) of patients at high risk for falls as compared to 39.7% (n=23) with triage questions alone, a significant increase in patients screening at risk for falls (p<0.01, 1 degree of freedom). Only 10 of the 35 patients at risk for falls had been told they were at risk for falls in the past, leading to 25 new diagnoses of high risk (43.1% of total patients), 10 of which were made by the 4SBT alone.

Discussion

The ED is an important setting for fall risk screening and prevention, but previously developed screening tools have been inadequate. Following the CDC STEADI Guidelines by combining functional balance testing with triage screening questions identified a new population of older adults at risk for falls. Nursing administration of the 4 Stage Balance Test is feasible in the ED setting, although our use of a convenience sample suggests that the true rate of compliance is likely lower. On the other hand, the previously ambulatory patients who refused testing due to inability to stand or were too sick to be approached likely required admission and could be assessed later in their hospitalization. Another two patients were not screened because nursing staff were too busy to perform the exam. Despite these difficulties, this pilot study does prove the feasibility of a 40 second fall risk screening exam even in the context of a busy ED. Training materials for administering the 4SBT are available free from the CDC and readily available online (http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/index.html). If further research demonstrates improved outcomes with the addition of this screening measure, it could be easily implemented across the US.

Combining a verbal query of recent falls and risk factors with functional testing is the recommended algorithm for risk assessment per the CDC guidelines. However, the guidelines were developed for an outpatient clinic setting and recommend not proceeding to functional testing if the verbal query is negative. We found that in the ED the standard triage questions missed almost half of patients who were high risk by the 4SBT. Deferring functional testing if the verbal query is negative may miss many high risk patients. This could be because asking about historical risk factors is insufficient in the setting of the acute illness or injury that brought the patient to the ED, or because verbal risk assessments in general are insufficient, which has been suggested by others.8 Our data suggests that all older adults in the ED should proceed to functional testing.

The discordance between the triage query and the 4SBT is not unexpected. A verbal query identifies fall risk factors and historical falls. Similarly to the TUGT, the 4SBT alone is not sufficient to identify all fallers and the added information from the verbal query is still needed.9 The 4SBT measures static balance and will identify patients who, whether from neurological insults, peripheral neuropathy, weakness, vision deficits, or other etiologies, have difficulty with static balance that will predispose them to falls. These patients may not have fallen yet, but are at risk. Combining the two provides information about past and future fall risk.

The addition of a CDC-approved functional screening test for balance and falls risk also elevates ED falls risk screening from a focus on preventing falls just in the hours the patient is in the department to long term prevention. The majority of patients found to be at risk were unaware of their risk. The patient education provided and referral for outpatient follow up was a new intervention for those patients. Multidisciplinary fall risk interventions have had equivocal results in the past, but prior studies suggest that by focusing these interventions on high risk patients only, and by arranging for services (rather than just offering patient referrals), these interventions have a much higher likelihood of preventing falls and increasing quality of life. Improving our initial detection sensitivity is therefore likely to improve the overall outcomes of any fall prevention intervention.

This is a small pilot study of a convenience sample of ambulatory older adult ED patients, and therefore results may not be generalizable to the entire ED population or to other institutions. Patients who consented were willing to stand and undergo balance testing. Generalizing this test to all ambulatory older ED patients may reveal high rates of patients who are unwilling or unable to attempt the 4SBT. Additionally, this study does not link the detection of high risk for falls with ensuing fall rates, so this increased detection may not have clinical relevance.

As a result of this pilot study, all nurses in our ED are being trained to perform the 4SBT for those at risk of falls and prior to walking older adult patients. The assessment has been incorporated into ED care by means of an electronic medical record nursing rounding note. Additional research will evaluate which patients are receiving screening and whether positive falls risk assessments change patient management.

Conclusions

In summary, this is the first study to suggest that a standard verbal query may not be sufficient for the detection of older adults at risk of falls in the ED. The 4 Stage Balance Test is a feasible addition to risk stratification in the ED, and identifies significantly more patients at high risk for falls. Further research is needed to evaluate the predictive capabilities of this test for post-ED visit fall prediction and prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources/Disclosures: All authors report support by a grant from the Cummings Endowment for Research in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Ohio State University to perform this study. Additionally, LTS is supported by a Falls Prevention Coalition Grant from the Ohio Department of Health, Office of Injury Prevention Partnership. The use of REDCap database technology is supported by the Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science grant support via a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant, UL1TR001070.

Thank you to the undergraduate students (William Hartman, Nia Caldwell, and Matthew Swigonski) who helped with recruitment, Kimberly Payne, PT who initially proposed the 4 Stage Balance Test as a feasible ED based test, and all the ED nurses who identified possible trial participants and assisted with the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentations: Accepted for poster presentation at 2016 ACEP Research Forum. Southerland, LT, Slattery, L, Rosenthal, JA, Kegelmeyer, D, and Kloos, A. “Are triage questions sufficient to assess fall risk in the ED?”

Conflict of Interests: None reported.

Author Contributions: LTS, JAR, DK and AK conceived the study, designed the trial and obtained research funding. LTS, LS, and DK supervised the conduct of the study, data collection, and quality control. LTS and AK analyzed the study data. LTS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision.

References

- 1.Tirrell G, Sri-on J, Lipsitz LA, Camargo CA, Jr, Kabrhel C, Liu SW. Evaluation of older adult patients with falls in the emergency department: discordance with national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:461–467. doi: 10.1111/acem.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert M, McCaig LF, Ashman JJ. Emergency Department visits by persons aged 65 and older: United States 2009–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. NCHS data brief, no 130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter CR, Avidan MS, Wildes T, Stark S, Fowler SA, Lo AX. Predicting geriatric falls following an episode of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1069–1082. doi: 10.1111/acem.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens JA. The STEADI Tool Kit: A Fall Prevention Resource for Health Care Providers. IHS Prim Care Provid. 2013;39:162–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossiter-Fornoff JE, Wolf SL, Wolfson LI, Buchner DM. A cross-sectional validation study of the FICSIT common data base static balance measures. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M291–M297. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.6.m291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boye ND, Mattace-Raso FU, Van Lieshout EM, Hartholt KA, Van Beeck EF, Van der Cammen TJ. Physical performance and quality of life in single and recurrent fallers: data from the Improving Medication Prescribing to Reduce Risk of Falls study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:350–355. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver D. Falls risk-prediction tools for hospital inpatients. Time to put them to bed? Age Ageing. 2008;37:248–250. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoene D, Wu SM, Mikolaizak AS, et al. Discriminative ability and predictive validity of the timed up and go test in identifying older people who fall: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:202–208. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, Geller AI, Strasser DC. Analytical review: focus on fall screening assessments. PM R. 2013;5:609–621. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]