Abstract

As cesarean sections become a more common mode of delivery, they have become the most likely cause of vesicouterine fistula formation. The associated pathology with repeat cesarean deliveries may make repair of these fistulas difficult. Early robotic-surgery offers a 3-dimensional view of the operative field and allows for intricate movements necessary for complex suturing and dissection. These qualities are advantageous in vesicouterine fistula repair.

42 years old female day 12 post-LSCS in author hospital with history of bladder injury and folly's catheter in place since OR complain of gross hematuria for 8 days.

Keywords: Early robotic surgery, Vesicouterine fistula repair, With frank hematuria

Introduction

Vesicouterine fistulas are an uncommon phenomenon. Since the first case reported by Knipe in 1908, these fistulas have been estimated to account for 1–4% of all genitourinary fistulas.1, 2 During the first half of the century, prolonged labor and vaginal obstetric procedures contributed to the formation of vesicouterine fistulas. In 1957, Youssef reported on the syndrome which now bears his name: bladder injury during cesarean delivery that causes vesicouterine fistula formation. The classic symptoms of Youssef's syndrome are amenorrhea and cyclic hematuria coinciding with time of expected menstruation, or menouria.3 As lower uterine segment cesarean deliveries have increased in popularity, they have become the more common cause of vesicouterine fistula formation.4

Treatment options include conservative management, such as bladder decompression with indwelling Foley catheter or medical management to induce amenorrhea to aid in fistula healing. Surgical removal of the fistulous tract, historically via laparotomy, is also an option. As minimally invasive surgery becomes utilized more frequently in both gynecologic and urologic procedures, laparoscopic and even robotic-assisted laparoscopic repair of vesicouterine fistulas are viable treatment options.5, 6, 7, 8

We present the case of a robotic-assisted laparoscopic repair of a vesicouterine fistula occurring after a patient's fourth cesarean delivery.

Case report

A 42 year old lady P4+1 she has a history of 3 previous caesarean section and Dilation and Evacuation (D&E), medically free.

She was admitted to our hospital in 22/4/2012. She is post-Low Segment Caesarean Section (LSCS) day 12 was done in other hospital, she has a history of bladder injury and catheter in place since the operation, we do not know if the patient had a history of voiding problem because she came already with folly catheter, she came to us complain of hematuria it was light since the Operation but it's start to be frank hematuria with clots before 8 day, she does not define incontinence. On examination the abdomen was soft and lax with mild suprapubic tenderness not radiated, the Patient vital was stable, her lab investigation Na 138 mmol/L, K 3 mmol/L, creatinine 63 mmol/L, urea 6.9 mmol/L, WBC 5.72 × 10e9/L, HBG 11.1 × 10e9/L, platelet 397 × 10e9/L, urinalysis was negative and culture also show no growth, prothrombin time (PT) 10.4 s, INR 0.9.

The Patient went to CT scan and shows ureterovesical fistula (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(A, B) The CT demonstrated a fistula between the dome of the bladder and the endometrial cavity (ureterovesical fistula). No signs of urinoma as or ureteric injury.

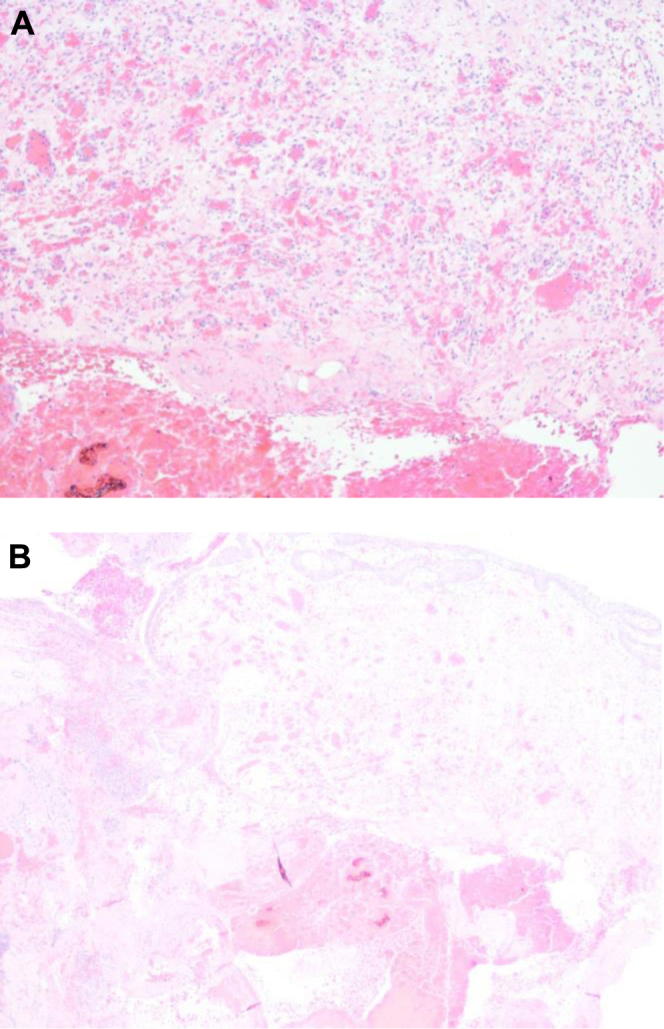

The Patient underwent Robotic Early Vesicouterine Fistula Repair under General Anesthesia, supine position, the procedure was done successfully with minimal blood loss and without any complication. And the sample was send to the histopathological lab for more investigation. The sample shows extensive fibrosis, congestion, acute and chronic inflammation (Fig. 2A, B).

Figure 2.

(A, B) Acute and chronic inflammation, congestion, and extensive fibrosis.

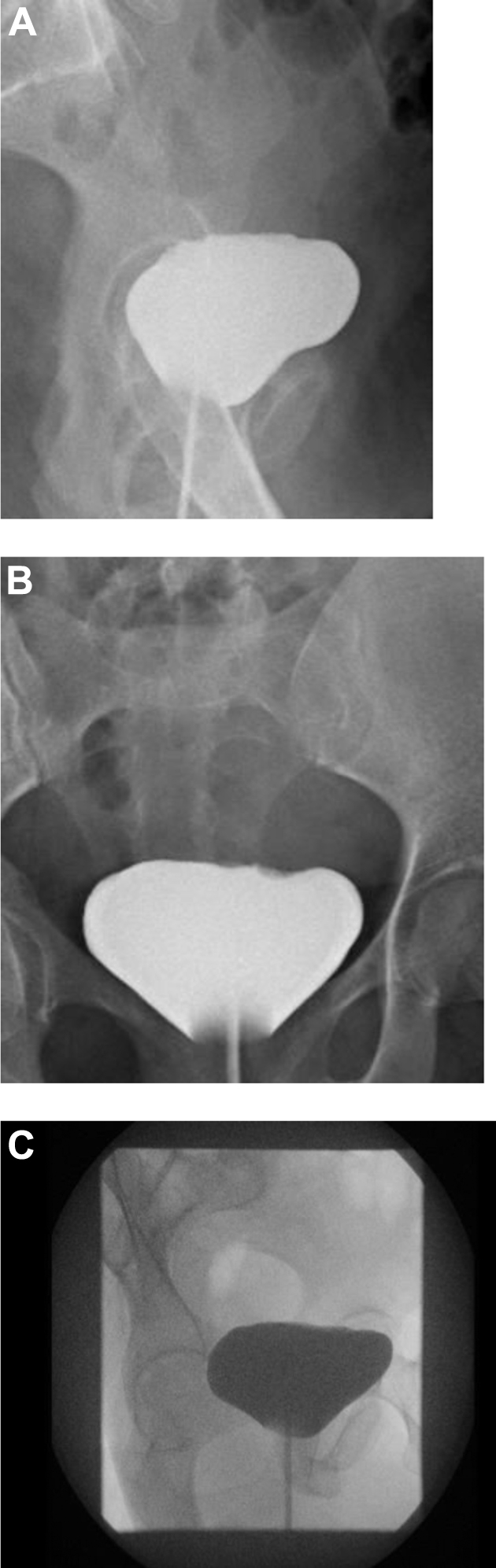

After the operation the patient tolerating well orally, moving around the word, she was in mild pain, the urine output (clean) without hematuria passing flatus, the drain was 23 cc/24 hr (heamoserous) fluid in the first 2 day post-op and in the third it was 19 cc/24 hr. She does not developed fever and the wound was clean, in the fourth day post-op the patient discharged from the hospital with orally antibiotic and appointment after 1 week to do cystograme test (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(A, B, C) Cystograme was performed utilizing about 120 mL of water soluble contrast media.

The cystograme was performed and shows no evidence of vesicouterine fistula and leakage.

The result show, that was no evidence of contrast leakage or appear of the vesicouterine fistula, but there was some irregularity of the urinary bladder dome.

Discussion

Vesicouterine fistulas are an uncommon occurrence, although with the rising numbers of cesarean deliveries being performed, the frequency of these genitourinary fistulas may increase. Bladder injury during cesarean delivery has been frequently reported as a cause of vesicouterine fistulas. This may involve inadequate downward mobilization of the bladder, direct injury to the portion directly adherent to the lower uterine segment or anterior vaginal wall, aberrant suture placement or excessive devascularization or infection from cauterization, clamping, or hematoma formation.9 Prior uterine scars may also play a role in the formation of vesicouterine fistulas. During labor, the thinning of the lower uterine segment may cause uterine scar dehiscence. This shearing force during uterine rupture may be transmitted to the bladder, causing subsequent development of a fistula.10 Other less common causes of vesicouterine fistula include uterine rupture, manual removal of the placenta, placenta percreta, local tumor invasion or radiation injury, and contraceptive intrauterine device causing uterine injury. Rarely, congenital anomalies, pelvic infections, such as tuberculosis or actinomycosis, and uterine artery embolization have been implicated as causes of these fistulas.9, 11, 12

Diagnosis of vesicouterine fistulas is often accomplished with a combination of patient symptoms and clinical examination. A tampon test may be performed after the patient ingests medication containing a dye excreted in the urine, such as phenazopyridine or Prosed (Ferring Pharmaceutical, Parsippany, NJ). The clinician may also instill saline combined with methylene blue or indigo carmine into the bladder and monitor extravasation through the cervical os. Simple radiological methods, such as an intravenous urogram or cystometrogram can confirm and identify the exact location of the fistula. Sonohysterography, transvaginal ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging have also been utilized to diagnose vesicouterine fistulas.12, 13, 14

Management of vesicouterine fistulas can either be approached conservatively or through surgery. If the fistula occurs soon after delivery, bladder decompression with a Foley catheter for at least 3 weeks has been shown to be effective in aiding spontaneous closure.15 Others have advocated hormonal suppression of menstruation with bladder decompression to allow the tract to close without the continuous flow of menstrual blood. Oral contraceptives, progestational agents, and gonadotropin releasing hormone analogs have been used to induce amenorrhea.9 Józwik and Józwik16 discovered that when hormonal suppression was utilized, the likelihood of spontaneous resolution of the fistula was 89% as opposed to <5% without suppression. Cystoscopic fulguration of the vesicular portion of the fistula has also been proven to be effective in specific cases of vesicouterine fistula.17, 18

When conservative management fails, surgical treatment has been the mainstay of therapy. The basic surgical principles for repair of a genitourinary fistula are wide exposure with liberal excision of scar tissue around the fistula; tension-free closure of the wound in multiple layers with absorbable suture; and possible transposition of an omental or myouterine flap to obliterate dead space and prevent hematoma formation.9 The method of performing the repair has traditionally been approached through a laparotomy incision, but recently, laparoscopic and robotic repair have been accomplished.5, 6, 7, 8

Conclusion

Early robotic fistula repair is a feasible surgical option for successful repair of vesicouterine fistula with minimal bleeding intra-operatively and less morbidity post-operatively with short hospital stay.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Knipe W.H.W. Vesico-uterine fistula. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1908;57:211–217. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibachie G., Njoku O. Vesico-uterine fistula. Br J Urol. 1985;57:438–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1985.tb06305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youssef A.F. Menouria follow lower segment cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1957;73:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(57)90384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tancer M.L. Vesicouterine fistula – a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1986;41:743–753. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198612000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miklos J.R. Laparoscopic treatment of vesicouterine fistula. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:339–341. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(99)80073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramalingam M., Senthil K., Pai M., Renukadevi R. Laparoscopic repair of vesicouterine fistula – a case report. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19:731–733. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0480-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahapatra P., Bhattacharyya P. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal repair of high-up urinary bladder fistula: a review of 12 cases. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:635–639. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemal A.K., Sharma N., Mukherjee S. Robotic repair of complex vesicouterine fistula with and without hysterectomy. Urol Int. 2009;82:411–415. doi: 10.1159/000218529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip S.K., Leung T.Y. Vesicouterine fistula: an updated review. Int Urogynecol J. 1998;9:252–256. doi: 10.1007/BF01901500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yip S.K., Fung H.Y., Wong W.S., Brieger G. Vesico-uterine fistula – a rare complication of vacuum extraction in a patient with previous cesarean section. Br J Urol. 1997;80:502–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price N., Golding S., Slack R.A., Jackson S.R. Delayed presentation of vesicouterine fistula 12 months after uterine artery embolisation for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:205–207. doi: 10.1080/01443610601157273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkatib M., Franco A.M., Fynes M.M. Vesicouterine fistula following cesarean delivery – ultrasound diagnosis and surgical management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:183–185. doi: 10.1002/uog.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy J.M., Lee G., Sharma S.D. Vesicouterine fistula: MRI diagnosis. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1876–1878. doi: 10.1007/s003300050939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Memon M.A., Zieg D.A., Neal P.M. Vesicouterine fistula twenty years following brachytherapy for cervical cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998;32:293–295. doi: 10.1080/003655998750015485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rifaei M., Al-Salmy S., Al-Rifaei A., Salama A. Vesicouterine fistula-variable clinical presentation. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:287–289. doi: 10.3109/00365599609182308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Józwik M., Józwik M. Spontaneous closure of vesicouterine fistula. Account for effective hormonal treatment. Urol Int. 1999;62:183–187. doi: 10.1159/000030388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina L.R., Lynne C.M., Politano V.A. Treatment of vesicouterine fistula by fulguration. J Urol. 1989;141:1422–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravi B., Schiavello H., Abayev D., Kazimir M. Conservative management of vesicouterine fistula. A report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]