Abstract

Citrus are sensitive to boron (B)-toxicity. In China, B-toxicity occurs in some citrus orchards. So far, limited data are available on B-toxicity-responsive proteins in higher plants. Thirteen-week-old seedlings of “Sour pummelo” (Citrus grandis) and “Xuegan” (Citrus sinensis) was fertilized every other day until dripping with nutrient solution containing 10 μM (control) or 400 μM (B-toxicity) H3BO3 for 15 weeks. The typical B-toxic symptom only occurred in 400 μM B-treated C. grandis leaves, and that B-toxicity decreased root dry weight more in C. grandis seedlings than in C. sinensis ones, demonstrating that C. sinensis was more tolerant to B-toxicity than C. grandis. Using a 2-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) based MS approach, we identified 27 up- and four down-accumulated, and 28 up- and 13 down-accumulated proteins in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively. Most of these proteins were isolated only from B-toxic C. sinensis or C. grandis roots, only nine B-toxicity-responsive proteins were shared by the two citrus species. Great differences existed in B-toxicity-induced alterations of protein profiles between C. sinensis and C. grandis roots. More proteins related to detoxification were up-accumulated in B-toxic C. grandis roots than in B-toxic C. sinensis roots to meet the increased requirement for the detoxification of the more reactive oxygen species and other toxic compounds such as aldehydes in the former. For the first time, we demonstrated that the active methyl cycle was induced and repressed in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively, and that C. sinensis roots had a better capacity to keep cell wall and cytoskeleton integrity than C. grandis roots in response to B-toxicity, which might be responsible for the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis. In addition, proteins involved in nucleic acid metabolism, biological regulation and signal transduction might play a role in the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis.

Keywords: boron-toxicity, Citrus grandis, Citrus sinensis, 2-DE, proteome, roots

Introduction

Boron (B) is an essential micronutrient for higher plants (Warington, 1923), where its most important role is associated with cell wall formation, functioning, and strength (Blevins and Lukaszewski, 1998). However, B will become toxic to crops when present in excess (Ben-Gal and Shani, 2003; Chen et al., 2012). B-toxicity is common in areas with high B concentration in underground water mainly resulting from the over-application of B fertilizer (Smith et al., 2013). In China, B-toxicity occurs in some citrus orchards. Up to 74.8 and 22.9% of pummelo (Citrus grandis) orchards in Pinghe, Zhangzhou, China, are excess in leaf B and soil water-soluble B, respectively (Li et al., 2015).

Plants have developed various mechanisms to cope with B-toxicity. Usually, antioxidant system will be activated to defense oxidative damage caused by B-toxicity (Cervilla et al., 2007; Ardic et al., 2009). Antioxidant compounds such as ascorbate and reduced glutathione (GSH) and antioxidant enzymes such as ascorbate peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione reductase (GR) are involved in the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Han et al., 2009; Erdal et al., 2014). B-tolerant plant leaves are characterized by a lower B concentration relative to B-sensitive ones, possibly due to a decreased uptake of B into both roots and shoots (leaves) (Camacho-Cristóbal et al., 2008). Sheng et al. (2010) showed that B-tolerant Newhall navel orange trees grafted on Carrizo citrange accumulated more B in roots and leaves than B-sensitive Skagg's Bonanza naval orange trees grafted on Carrizo citrange when exposed to B-toxicity, implying that the former must possess inner mechanisms to tolerate high level of B. Huang et al. (2014) reported that under B-toxicity, total B level was similar between B-tolerant Citrus sinensis and B-sensitive C. grandis roots (leaves), while C. sinensis leaves had lower free B and higher bound B than C. grandis leaves, which might contribute to the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis. Our recent work with C. sinensis and C. grandis demonstrated that miR397a played a key role in citrus B-tolerance by targeting two laccase genes involved in secondary cell-wall biosynthesis (Huang et al., 2016). Similar result has been obtained on Poncirus trifoliata (Jin et al., 2016). To conclude, the mechanisms for plant B-tolerance are not fully understood yet.

A comprehensive investigation of B-toxicity-responsive proteins will be useful for us to unveil the inner mechanisms of B-tolerance in specific plant species. So far, knowledge on B-toxicity-induced alterations of protein profiles in higher plants is limited. Demiray et al. (2011) used a 2-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) based MS approach to identify six B-toxicity-responsive proteins from carrot roots. Atik et al. (2011) used a 2-DE technique to investigate the effects of B-toxicity on protein profiles in barley leaves, suggesting that a B-toxicity-responsive vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) subunit E was involved in barley B-tolerance.

In higher plants, citrus are sensitive to B-toxicity (Eaton, 1935; Papadakis et al., 2004). Since B is phloem immobile in citrus (Konsaeng et al., 2005), the typical B-toxic symptom (chlorotic and/or necrotic patches) first develops in the older leaves and extends progressively from the old leaves to the young leaves (Han et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2014; Sang et al., 2015). It was indicated that great differences existed in B-tolerance among citrus species and/or genotypes (Chen et al., 2012). For example, when C. sinensis and C. grandis seedlings were submitted to 400 μM B for 15 weeks, the typical B-toxic symptom only occurred in the latter (Guo et al., 2014; Sang et al., 2015). We previously investigated the differences in B-toxicity-induced alterations of gene expression profiles in roots and leaves and of protein profiles in leaves between B-tolerant C. sinensis and B-sensitive C. grandis and revealed some adaptive responses of citrus to B-toxicity (Guo et al., 2014, 2016; Sang et al., 2015). Thus, B-toxicity-responsive proteins in roots should be different between C. sinensis and C. grandis. In this study, we used a 2-DE based MS approach to investigate comparatively B-toxicity-induced alterations of protein profiles in B-tolerant C. sinensis and B-sensitive C. grandis seedlings roots and corroborated the above hypothesis. For the first time, we demonstrated that the active methyl cycle was upregulated and downregulated in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively, and that C. sinensis roots had a better capacity to keep cell wall and cytoskeleton integrity than C. grandis roots when exposed to B-toxicity, which might be involved in the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture conditions

This study was conducted at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China. Seeds of “Sour pummelo” (C. grandis) and “Xuegan” (C. sinensis) were germinated in clean river sand in plastic trays. Five weeks after germination, uniform seedlings with a single stem were transplanted to 6 L pots (two seedlings per pot) filled with clean river sand. Seedlings were grown in a greenhouse under natural photoperiod. Eight weeks after transplanting, each pot was fertilized every other day until dripping with nutrient solution (ca. 500 mL) containing 10 μM (control) or 400 μM (B-toxicity) H3BO3 for 15 weeks as described previously by Guo et al. (2014) and Sang et al. (2015). Thereafter, fully expanded (ca. 7-week-old) leaves were used for all the measurements. Leaf discs (0.2826 cm2 in size) were punched from each leaf using a hole puncher of 0.6 cm in diameter at noon at full sun and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Approximately 5-mm-long white root apices were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after they were collected from the same seedlings used for sampling leaves. Both root and leaf samples were stored at −80°C until RNA and protein extraction, and the assay of malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, H2O2 production and enzyme activities. The remaining seedlings that were not sampled were used to measure root dry weight (DW) and B concentration in fibrous roots, root apices and leaves.

Measurements of root DW, and B and MDA concentrations and H2O2 production in roots and leaves

Roots of ten seedlings per treatment from 10 pots were harvested from the remaining seedlings and their DW was measured after being dried at 70°C for 48 h.

Fibrous roots, root apices and ca. 7-week-old fully expanded leaves (midribs and petioles removed) collected from the remaining seedlings were dried at 70°C, then ground to pass a 40-mesh sieve. Root and leaf B concentration was assayed by ICP emission spectrometry after microwave digestion with HNO3 (Wang et al., 2006). There were four replicates per treatment.

Root and leaf MDA was extracted and assayed according to Hodges et al. (1999). There were four replicates per treatment.

Root and leaf H2O2 production was determined according to Chen et al. (2005). About 40 mg frozen roots or 15 frozen leaf discs were incubated in 2 mL reaction mixture containing 50 mM of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.05% (w/v) of guaiacol and 5 U of horseradish peroxidase (Product No. 77332, lyophilized, powder, beige, ~150 U mg−1, Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Then, absorbance was assayed at 470 nm. There were four replicates per treatment.

Root protein extraction, 2-DE and image analysis

Approximately 1 g frozen roots collected equally from five seedlings (one seedling per pot) were mixed as one biological replicate. There were three biological replicates for each treatment (total of 15 seedlings from 15 pots). Proteins were independently extracted thrice from B-toxic and control samples according to You et al. (2014) using a phenol extraction procedure in order to ensure result reproducibility. Sample protein concentration was assayed according to Bradford (1976). 2-DE and image analysis were made according to Sang et al. (2015) and You et al. (2014). Gel images were obtained using Epson Scanner (Seiko Epson Corporation, Japan) at 300 dpi resolution. Image analysis was performed with PDQuest version 8.0.1 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The software was used to perform background subtraction, Gaussian fitting, gel alignment, spot detection, matching and normalization. The parameters used to spot detection were as follow: sensitivity 6.05, size scale 3, min peak 600, and local regression model was selected to conduct spot normalization. The spot intensity was expressed as relatively abundant intensity that normalized by total intensities of all spots in one gel. After manual processing, the candidate spots in all triplicate gels were submitted to ANOVA analysis. A protein spot was considered differentially abundant when it had both a P < 0.05 and a fold change of > 1.5.

Protein identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS and bioinformatic analysis

MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS-based protein identification was performed on an AB SCIEX 5800 TOF/TOF (AB SCIEX, Shanghai, China) according to You et al. (2014) and Peng et al. (2015). Briefly, spots were excised from the colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue stained gels and plated into a 96-well microtiter plate. Excised spots were first destained twice with 60 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 and 50% (v/v) acetonitrile, and then dried twice with 60 μL of acetonitrile. Afterwards, the dried pieces of gels were incubated in ice-cold digestion solution [trypsin (sequencing-grade modified trypsin V5113, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) 12.5 ng/μL and 20 mM NH4HCO3] for 20 min, and then transferred into a 37°C incubator for digestion overnight. Peptides in the supernatant were collected after extraction twice with 60 μL extract solution [5% (v/v) formic acid in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile]. The resulting peptide solution was dried under the protection of N2. Before MS/MS analysis, the pellet was redissolved in 0.8 μL matrix solution [5 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid diluted in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 50% (v/v) acetonitrile]. Then the mixture was spotted onto a MALDI target plate (AB SCIEX, Shanghai, China). MS analysis of peptide was performed on an AB SCIEX 5800 TOF/TOF. The UV laser was operated at a 400 Hz repetition rate with a wavelength of 355 nm. The accelerated voltage was operated at 20 kV, and mass resolution was maximized at 1,600 Da. Myoglobin digested with trypsin was used to calibrate the mass instrument with internal calibration mode. All acquired spectra of samples were processed using TOF/TOF Explorer™ Software (AB SCIEX, Shanghai, China) in a default mode. The data were searched by GPS Explorer (Version 3.6) with the search engine MASCOT (Version 2.3, Matrix Science Inc., Boston, MA). The search parameters were as follows: viridiplantae database (1,850,050 sequences; 6,42,453,415 residues), trypsin digest with one missing cleavage, MS tolerance was set at 100 ppm, MS/MS tolerance was set at 0.6 Da. At least two peptides were required to match for each protein. Protein identifications were accepted if MASCOT score was not less than 75, and the number of matched peptides was not less than five or the sequence coverage was not less than 20% (Lee et al., 2010; You et al., 2014). Searches were also performed against the C. sinensis databases (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias$=$Org_Csinensis).

Bioinformatics analysis of proteins was performed according to Yang et al. (2013).

Principal components analysis (PCA) of differentially abundant proteins (DAPs)

The ratios of all the DAPs from B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots were normalized and transformed for the PCA using Princomp function in R circumstance. The first two components were selected and used to visualize two loadings against each other to investigate the relationships between the variables (Mardia et al., 1979). The PCA loading plots were carried out in triplicate.

qRT-PCR analysis

Approximately 300 mg frozen roots collected equally from five seedlings (one seedling per pot) were pooled as one biological replicate. qRT-PCR analysis was run in three biological and two technical replicates for each treatment (total of 15 seedlings from 15 pots) according to Zhou et al. (2013). In this study, we randomly selected ten DAPs from each citrus species for qRT-PCR analysis. A total of 20 DAPs were selected from B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots. Specific primers were designed from the corresponding sequences of these selected DAPs in citrus genome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias$=$Org_Csinensis) using Primer Primier Version 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft International, CA, USA). The sequences of the F and R primers used were listed in Table S1. For the normalization of gene expression and reliability of quantitative analysis, two citrus genes [C. sinensis NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; gi|985455672) and C. sinensis DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit 4 (RPII; gi|985473508] were selected as internal standards and the roots from control seedlings were used as reference sample, which was set to 1.

Assay of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase (SAMS) and adenosine kinase (ADK)

Both ADK and SAMS were extracted according to Shen et al. (2002) by homogenizing ca. 100 mg of frozen roots in 1 mL extraction buffer including 100 mM of Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 20% (w/v) of glycerol, 20 mM of β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT) at 4°C. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was used immediately for enzyme assay. There were four replicates per treatment.

Total SAMS activity was assayed as described by Kim et al. (1992) and Shen et al. (2002). Briefly, 135 μL of an enzyme extract was incubated in 0.45 mL of a reaction mixture containing 100 mM of Tris (pH 8.0), 30 mM of MgSO4, 10 mM of KCl, 20 mM of ATP, and 5 mM of methionine. Blank contained all reagents except for methionine. Reaction was incubated for 1 h at 25°C and was terminated by adding 0.5 mL of 6% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and the phosphate (Pi) released from the substrate was determined as described by Smith et al. (1984) by adding 0.6 mL of an assay mixture containing 6 parts of 3.6 mM ammonium molybdate in 0.5 M H2SO4, and 1 part of 10% (w/v) ascorbic acid. The sample was incubated at 37°C for 60 min and the absorbance measured at 820 nm.

Root ADK activity was assayed according to Chen and Eckert (1977) and Lindberg et al. (1967) in 1 mL of a reaction mixture containing 20 mM of Tris-maleate (pH 5.8), 0.7 mM of ATP, 0.25 mM of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 0.2 mM of NADH, 0.5 mM of MgCl2, 50 mM of KCl, 0.05 mM of adenosine, 5 U of pyruvate kinase, 5 U of lactate dehydrogenase, and 0.1 mL of enzyme extract. The reaction mixture was always preincubated for 10 min at room temperature (25°C) with all of the regents before starting the reaction by the addition of adenosine.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

There were 20 pots (40 seedlings) per treatment in a completely randomized design. Experiments were performed with 3–10 replicates. Significant differences among four treatments were analyzed by two (species) × two (B levels) ANOVA and four means were separated by the Duncan's new multiple range test at P < 0.05. Significant tests between two means (B-toxicity and control) were performed by unpaired t-test at P < 0.05 level.

Results and discussion

C. sinensis was more tolerant to B-toxicity than C. grandis

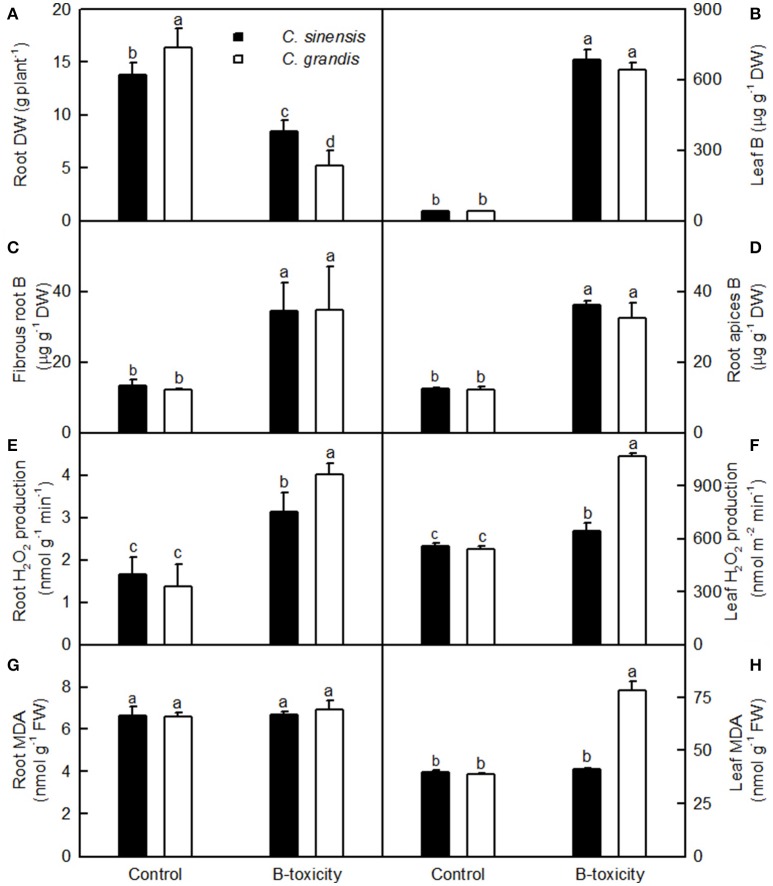

In previous studies, we showed that a concentration of 400 μM B is suitable for the comparative investigation of B-tolerance between B-tolerant C. sinensis and B-sensitive C. grandis. The typical B-toxic symptoms only occurred in C. grandis leaves (Guo et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2014; Sang et al., 2015). We therefore decided to use this B treatment in the present work to reveal specific root proteome signatures in tolerant and sensitive citrus species. As shown in Figures 1A–D, 400 μM B-treatment greatly decreased root DW, increased the concentration of B in leaves, fibrous roots and root apices, and the concentration of B in 400 μM B-treated leaves was far more than the sufficiency range of 30–100 mg kg−1 DW for citrus (Chapman, 1968). Thus, seedlings that received 10 and 400 μM B are considered as B-toxic and B-sufficient (control), respectively.

Figure 1.

Effects of B-toxicity on root DW (A), B concentration in leaves (B), fibrous roots (C) and root apices (D), H2O2 production in roots (E) and leaves (F), and MDA concentration in roots (G) and leaves (H). Bars represent means ± SD (n = 10 for root DW and 4 for other parameters). Differences among four treatments were analyzed by two (species) × two (B levels) ANOVA. Different letters above the bars indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05.

Our results showed that the B-toxicity-induced decrease in root DW (Figure 1A) and increase in H2O2 production in roots and leaves (Figures 1E,F) were greater in C. sinensis seedlings than in C. grandis ones, and that B-toxicity increased the concentration of MDA only in C. grandis leaves (Figure 1H). In addition, the typical visible B-toxic symptom only occurred in B-toxic C. grandis leaves, but was not found in B-toxic C. sinensis leaves except for very few seedlings (Figure S1). Previous studies showed that B-toxicity only decreased the concentrations of phosphorus (P) and total soluble proteins in C. grandis roots (Guo et al., 2016). Based on these results, we concluded that C. sinensis had higher B-tolerance than C. grandis.

Protein yield and DAPs in B-toxic roots

Protein yield did not differ among four treatment combinations (Table 1). After Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining, more than 800 clear and reproducible protein spots were discovered on each gel. The number of protein spots per gel were similar among the four treatment combinations (Table 1 and Figure 2; Figure S2), as obtained on C. sinensis and C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Protein yield, number of spots, number of variable spots and number of identified differentially abundant protein spots in Citrus sinensis and Citrus grandis roots.

| Citrus sinensis | Citrus grandis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | B-toxicity | Control | B-toxicity | |

| Protein yield (mg g−1 FW) | 13.30 ± 0.26a | 13.25 ± 0.15a | 11.26 ± 0.39a | 10.52 ± 0.18a |

| Number of spots per gel | 821 ± 41a | 824 ± 31a | 833 ± 40a | 818 ± 27a |

| NUMBER OF VARIABLE SPOTS | ||||

| Increase in relative abundance | 43 | 35 | ||

| Decrease in relative abundance | 5 | 20 | ||

| Total | 48 | 55 | ||

| NUMBER OF IDENTIFIED DIFFERENTIALLY ABUNDANT PROTEIN SPOTS | ||||

| Increase in relative abundance | 27 | 28 | ||

| Decrease in relative abundance | 4 | 13 | ||

| Total | 31 | 41 | ||

Data for protein yield and number of spots per gel are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters within a row indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

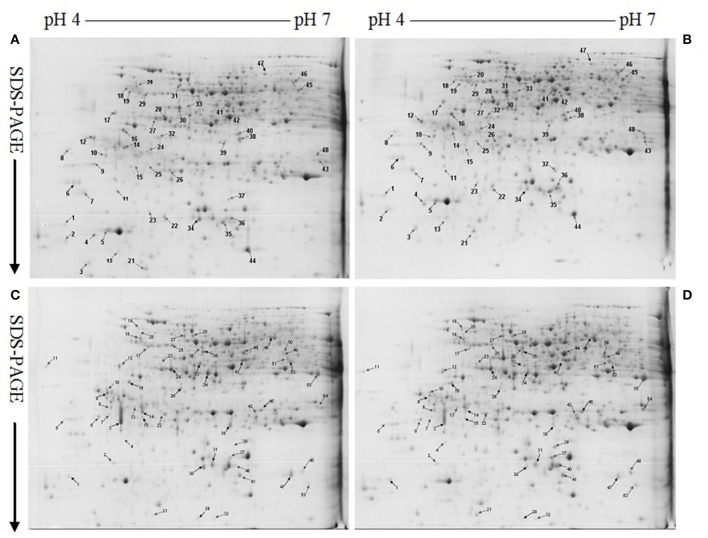

Figure 2.

Representative 2-DE images of proteins extracted from control (A,C) and B-toxic (B,D) roots. (A) Control roots of Citrus sinensis, (B) B-toxic root of C. sinensis, (C) Control roots of Citrus grandis, (D) B-toxic roots of C. grandis.

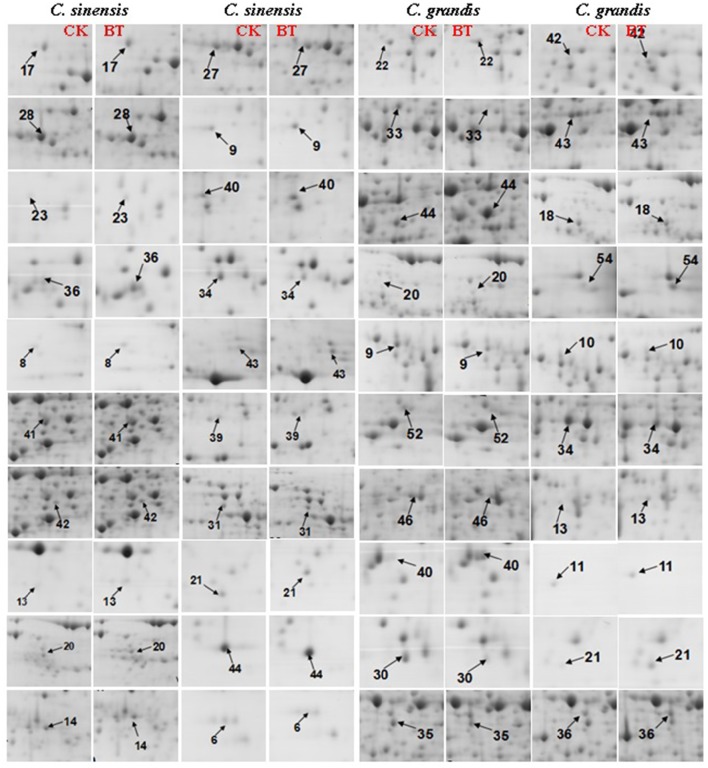

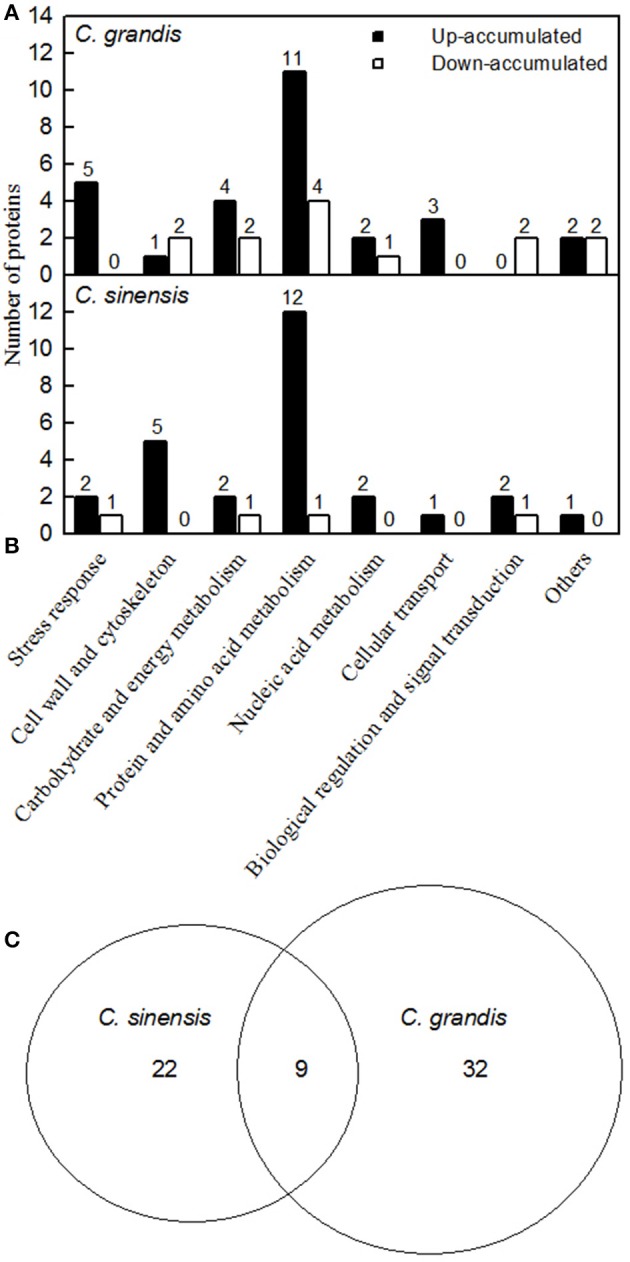

We detected 43 up- and five down-accumulated, and 35 up- and 20 down-accumulated protein spots from B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively. Twenty-seven up- and four down-accumulated, and 28 up- and 13 down-accumulated protein spots were identified from B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively after these differentially accumulated protein spots being submitted to the MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS-based identification (Table 1, Figures 2, 3 and Tables S2–S5). These DAPs were mainly involved in protein and amino acid metabolism, stress response, cell wall and cytoskeleton metabolism, carbohydrate and energy metabolism, nucleic acid metabolism, cellular transport, and biological regulation and signal transduction (Tables 2, 3 and Figures 4A,B). Most of B-toxicity-responsive proteins were isolated from B-toxic C. sinensis or C. grandis roots, only nine protein species with the same accession No. were shared by the both. Among the nine overlapping proteins, only five proteins displayed similar change trends in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots (Tables 2, 3 and Figure 4C). These results demonstrated that B-toxicity-responsive proteins greatly differed between C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, as obtained on B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Close-up views of the differentially abundant protein spots in control (CK) and B-toxic (BT) roots.

Table 2.

Differentially abundant proteins and their identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS in B-toxic Citrus sinensis roots.

| Spot No. | Protein identity | Accession no. | Mr(kDa)/pI Theor. | Mr (kDa)/pI Exp. | Reference species | Protein score | NMP | Ratio | Covered sequence (%) | Charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRESS RESPONSE | ||||||||||

| S16 | Heat shock protein 83 | gi|169296 | 80.77/4.95 | 81.1/5.0 | Ipomoea nil | 102 | 8 | 0.42 ± 0.20 | 14 | 1 |

| S32 | Mitochondrial chaperonin hsp60 | gi|20466256 | 61.242/5.66 | 60.3/5.18 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 288 | 22 | 1.92 ± 0.31 | 29 | 1 |

| S17 | Late-embryogenesis abundant protein 2 | gi|212552206 | 34.343/4.72 | 35.2/4.53 | Glycine max | 260 | 14 | 1.87 ± 0.31 | 36 | 1 |

| CELL WALL AND CYTOSKELETON | ||||||||||

| S30 | Actin | gi|6103623 | 41.564/5.30 | 42.6/5.81 | Picea rubens | 637 | 25 | 1.63 ± 0.10 | 50 | 1 |

| S29 | Alpha-tubulin | gi|321437427 | 46.368/4.90 | 46.2/4.8 | Musa acuminata AAA Group | 647 | 21 | 1.70 ± 0.26 | 47 | 1 |

| S18 | Beta-tubulin 14 | gi|166343835 | 49.98/4.76 | 50.4/4.6 | Gossypium hirsutum | 618 | 31 | 2.97 ± 0.20 | 40 | 1 |

| S19 | Tubulin β-1 chain | gi|332197637 | 50.185/4.68 | 51.6/4.91 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 660 | 27 | 2.19 ± 0.46 | 33 | 1 |

| S3 | Profilin | gi|12659206 | 14.133/4.90 | 13.8/4.94 | Corylus avellana | 89 | 9 | 1.57 ± 0.04 | 43 | 1 |

| CARBOHYDRATE AND ENERGY METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| S27 | Adenosine kinase 2, partial | gi|149391003 | 26.477/4.88 | 25.9/5.63 | Oryza sativa Indica Group | 80 | 7 | 1.82 ± 0.15 | 21 | 1 |

| S28 | Adenosine kinase isoform 1T-like protein | gi|82400168 | 37.549/5.01 | 38.6/5.71 | Solanum tuberosum | 113 | 6 | 1.81 ± 0.14 | 20 | 1 |

| S47 | Malate dehydrogenase, partial | gi|160690776 | 14.017/7.03 | 15.4/5.05 | Citrus trifoliata | 220 | 6 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 38 | 1 |

| PROTEIN AND AMINO ACID METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| S9 | Proteasome subunit alpha type, putative | gi|255584432 | 27.0/4.73 | 27.8/4.75 | Ricinus communis | 191 | 11 | 1.76 ± 0.12 | 42 | 1 |

| S12 | Elongation factor 1-delta 1 | gi|226505926 | 24.767/4.39 | 23.8/4.38 | Zea mays | 219 | 11 | 2.41 ± 0.31 | 20 | 1 |

| S15 | Elongation factor 2 | gi|195646972 | 93.862/6.00 | 94.2/6.51 | Zea mays | 143 | 8 | 2.90 ± 0.21 | 9 | 1 |

| S23 | Translation initiation factor | gi|197312901 | 16.419/4.98 | 16.2/5.12 | Rheum australe | 188 | 7 | 1.72 ± 0.08 | 26 | 1 |

| S40 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 beta subunit-like | gi|82621136 | 29.831/6.08 | 30.6/6.54 | Solanum tuberosum | 101 | 9 | 1.85 ± 0.15 | 32 | 1 |

| S36 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A1 | gi|217038830 | 17.387/5.60 | 17.2/5.7 | Glycine max | 153 | 10 | 3.13 ± 0.72 | 28 | 1 |

| S34 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (2) | gi|19702 | 17.353/5.60 | 18.5/6.4 | Nicotiana plumbaginifolia | 120 | 10 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 58 | 1 |

| S8 | Alpha chain of nascent polypeptide associated complex | gi|124484511 | 21.911/4.32 | 22.1/4.52 | Nicotiana benthamiana | 242 | 8 | 2.03 ± 0.37 | 20 | 1 |

| S43 | Alanine aminotransferase 2 | gi|332197185 | 47.68/6.32 | 48.2/6.61 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 138 | 5 | 2.28 ± 0.30 | 11 | 1 |

| S41 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase 2 | gi|1655578 | 42.977/5.51 | 43.3/5.93 | Catharanthus roseus | 241 | 19 | 1.89 ± 0.14 | 47 | 1 |

| S39 | 5-methyltetrahy dropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase, putative | gi|255569484 | 84.668/6.09 | 85.6/6.52 | Ricinus communis | 373 | 19 | 1.97 ± 0.16 | 27 | 1 |

| S42 | Transaminase mtnE, putative | gi|255562088 | 50.396/6.95 | 51.8/6.05 | Ricinus communis | 244 | 10 | 1.74 ± 0.16 | 22 | 1 |

| S31 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | gi|295291644 | 63.583/6.49 | 64.6/6.62 | Catharanthus roseus | 286 | 16 | 2.07 ± 0.38 | 21 | 1 |

| NUCLEIC ACID METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| S13 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 4 | gi|332643299 | 14.12/5.03 | 15.6/8.68 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 133 | 4 | 1.85 ± 0.13 | 33 | 1 |

| S21 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein | gi|7024451 | 16.839/4.98 | 17.4/7.85 | Citrus unshiu | 227 | 10 | 1.92 ± 0.31 | 28 | 1 |

| CELLULAR TRANSPORT | ||||||||||

| S20 | Vacuolar H+-ATPase B subunit | gi|4519264 | 54.329/4.91 | 55.6/4.91 | Citrus unshiu | 641 | 35 | 1.67 ± 0.15 | 53 | 1 |

| BIOLOGICAL REGULATION AND SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION | ||||||||||

| S44 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 | gi|255571035 | 176.41/5.09 | 179.1/6.3 | Ricinus communis | 136 | 4 | 1.51 ± 0.16 | 20 | 1 |

| S14 | 14-3-3 family protein | gi|291162645 | 29.404/4.74 | 30.5/4.71 | Dimocarpus longan | 241 | 7 | 1.52 ± 0.14 | 33 | 1 |

| S6 | Translationally controlled tumor-like protein | gi|115187479 | 19.116/4.54 | 20.0/4.7 | Arachis hypogaea | 286 | 9 | 0.44 ± 0.14 | 31 | 1 |

| OTHER | ||||||||||

| S37 | Unnamed protein product, partial | gi|296088008 | 17.163/5.21 | 18.2/7.93 | Vitis vinifera | 709 | 17 | 1.84 ± 0.27 | 51 | 1 |

Spot number corresponds to the 2-DE gel imagines in Figures 2A,B. NMP means the number of peptides. Ratio means the ratio of B-toxic roots to controls and the values were the means ± SE of three replicates. Covered sequence (%) means the ratio of the number of amino acids of the matched peptides to the number of amino acids of the full-length protein. Proteins shared by C. sinensis and C. grandis roots were marked in bold.

Table 3.

Differentially abundant proteins and their identification by MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS in B-toxic Citrus grandis roots.

| Spot No. | Protein identity | Accession No. | Mr(kDa)/pI Theor. | Mr (kDa)/pI Exp. | Reference species | Protein score | NMP | Ratio | Covered sequence (%) | Charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRESS RESPONSE | ||||||||||

| G32 | Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, partial | gi|2274917 | 12.784/5.82 | 13.5/5.61 | Citrus sinensis | 179 | 7 | 1.91 ± 0.11 | 52 | 1 |

| G26 | Lactoylglutathione lyase, putative | gi|255554865 | 31.547/5.11 | 31.8/7.63 | Ricinus communis | 219 | 12 | 1.85 ± 0.18 | 40 | 1 |

| G16 | Heat shock protein 83 | gi|169296 | 80.820/4.95 | 81.4/5.12 | Ipomoea nil | 102 | 8 | 1.60 ± 0.17 | 14 | 1 |

| G19 | 60-kDa chaperonin-60 alpha -polypeptide precursor, partial | gi|289365 | 57.692/4.84 | 58.4/4.58 | Brassica napus | 435 | 26 | 1.92 ± 0.15 | 41 | 1 |

| G12 | Chilling-responsive protein | gi|153793260 | 35.739/4.85 | 36.4/4.6 | Nicotiana tabacum | 284 | 9 | 1.88 ± 0.27 | 12 | 1 |

| CELL WALL AND CYTOSKELETON | ||||||||||

| G52 | Alpha-1,4-glucan-protein synthase 1 | gi|195623832 | 40.905/6.60 | 40.2/6.21 | Zea mays | 422 | 20 | 0.48 ± 0.12 | 49 | 1 |

| G34 | Actin 1 | gi|255115691 | 41.665/5.31 | 41.9/5.14 | Boehmeria nivea | 169 | 12 | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 30 | 1 |

| G25 | Alpha-tubulin | gi|334261583 | 49.446/4.99 | 50.3/5.0 | Pellia endiviifolia | 297 | 12 | 2.02 ± 0.30 | 26 | 1 |

| CARBOHYDRATE AND ENERGY METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| G46 | ATP synthase subunit α | gi|222356608 | 40.289/8.59 | 41.6/8.9 | Afrothismia hydra | 323 | 13 | 0.47 ± 0.15 | 29 | 1 |

| G24 | Adenosine kinase isoform 1T-like protein | gi|82400168 | 37.572/5.01 | 37.2/5.16 | Solanum tuberosum | 113 | 6 | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 20 | 1 |

| G22 | Triosephosphate isomerase | gi|295687231 | 33.119/6.66 | 33.6/5.94 | Gossypium hirsutum | 316 | 12 | 2.17 ± 0.12 | 25 | 1 |

| G42 | Triosphosphate isomerase-like protein | gi|76573375 | 27.711/5.88 | 28.3/5.9 | Solanum tuberosum | 215 | 8 | 2.02 ± 0.17 | 23 | 1 |

| G51 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | gi|332198142 | 42.131/5.49 | 43.2/5.61 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 120 | 9 | 1.74 ± 0.24 | 15 | 1 |

| G50 | Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | gi|226509380 | 48.749/5.11 | 49.4/5.64 | Zea mays | 92 | 12 | 1.56 ± 0.16 | 51 | 1 |

| PROTEIN AND AMINO ACID METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| G6 | Proteasome subunit alpha type, putative | gi|255584432 | 27.017/4.73 | 27.8/4.75 | Ricinus communis | 191 | 11 | 1.77 ± 0.16 | 42 | 1 |

| G13 | 26S proteasome subunit RPN12 | gi|32700048 | 30.701/4.81 | 31.5/4.66 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 218 | 9 | 1.91 ± 0.18 | 29 | 1 |

| G48 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variant | gi|257196367 | 16.630/6.20 | 17.6/6.6 | Citrus sinensis | 438 | 22 | 1.63 ± 0.32 | 80 | 1 |

| G53 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 35 | gi|332198044 | 17.191/6.74 | 18.3/6.41 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 387 | 14 | 2.97 ± 0.70 | 47 | 1 |

| G29 | Polyubiquitin, partial | gi|284927592 | 11.992/8.2 | 12.3/5.12 | Citrus sinensis | 389 | 11 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 66 | 1 |

| G7 | Translation initiation factor IF6 | gi|332645889 | 26.482/4.63 | 27.8/4.52 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 246 | 6 | 1.74 ± 0.07 | 16 | 1 |

| G40 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A isoform VII | gi|33325129 | 17.471/5.60 | 18.2/5.9 | Hevea brasiliensis | 121 | 10 | 4.75 ± 1.19 | 40 | 1 |

| G11 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A1 | gi|217038830 | 17.397/5.60 | 17.9/5.58 | Glycine max | 239 | 13 | 2.27 ± 0.44 | 32 | 1 |

| G41 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A1 | gi|217038830 | 17.397/5.60 | 18.4/5.6 | Glycine max | 236 | 10 | 1.55 ± 0.12 | 65 | 1 |

| G30 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (2) | gi|19702 | 17.363/5.60 | 18.7/5.52 | Nicotiana plumbaginifolia | 120 | 10 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 58 | 1 |

| G33 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 1 family protein | gi|222861722 | 43.213/5.68 | 43.5/5.82 | Populus trichocarpa | 598 | 18 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 39 | 1 |

| G43 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 1 family protein | gi|222861722 | 43.213/5.68 | 44.1/5.73 | Populus trichocarpa | 677 | 17 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 45 | 1 |

| G44 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | gi|14600072 | 43.184/5.67 | 43.8/5.52 | Brassica juncea | 490 | 23 | 2.01 ± 0.26 | 33 | 1 |

| G27 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | gi|295291644 | 63.623/6.49 | 64.2/6.81 | Catharanthus roseus | 286 | 16 | 1.68 ± 0.04 | 21 | 1 |

| G28 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | gi|295291644 | 63.623/6.49 | 65.1/6.9 | Catharanthus roseus | 332 | 16 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | 16 | 1 |

| NUCLEIC ACID METABOLISM | ||||||||||

| G21 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein | gi|7024451 | 16.848/7.85 | 17.3/4.98 | Citrus unshiu | 227 | 10 | 2.64 ± 0.16 | 28 | 1 |

| G35 | DEAD-box RNA helicase-like protein | gi|283049402 | 46.935/5.48 | 47.2/5.6 | Prunus persica | 735 | 33 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | 50 | 1 |

| G36 | Spliceosome RNA helicase BAT1 | gi|226528292 | 45.146/6.03 | 48.1/6.52 | Zea mays | 434 | 24 | 1.97 ± 0.33 | 41 | 1 |

| CELLULAR TRANSPORT | ||||||||||

| G18 | Vacuolar H+-ATPase B subunit | gi|4519264 | 54.362/4.91 | 55.2/5.02 | Citrus unshiu | 641 | 35 | 1.80 ± 0.20 | 53 | 1 |

| G20 | Vacuolar H+-ATPase B subunit | gi|4519264 | 54.362/4.91 | 54.9/5.1 | Citrus unshiu | 121 | 13 | 1.80 ± 0.16 | 15 | 1 |

| G54 | GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran-A1 | gi|192913008 | 24.9/6.38 | 25.8/6.51 | Elaeis guineensis | 86 | 8 | 2.24 ± 0.03 | 28 | 1 |

| BIOLOGICAL REGULATION AND SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION | ||||||||||

| G9 | 14-3-3-like protein GF14 phi | gi|332193639 | 30.193/4.79 | 31.5/4.63 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 483 | 22 | 0.48 ± 0.19 | 53 | 1 |

| G10 | 14-3-3-like protein GF14 phi | gi|332193639 | 30.193/4.79 | 29.8/5.12 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 436 | 21 | 0.41 ± 0.16 | 54 | 1 |

| OTHERS | ||||||||||

| G15 | 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase2 | gi|162459589 | 41.665/6.08 | 42.4/6.31 | Zea mays | 110 | 11 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 31 | 1 |

| G49 | 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase2 | gi|162459589 | 41.665/6.08 | 42.8/6.25 | Zea mays | 98 | 11 | 0.49 ± 0.14 | 31 | 1 |

| G2 | Unnamed protein product, partial | gi|296088008 | 17.173/7.93 | 17.8/5.16 | Vitis vinifera | 503 | 13 | 1.69 ± 0.09 | 35 | 1 |

| G39 | Unnamed protein product, partial | gi|296088008 | 17.173/7.93 | 17.2/5.21 | Vitis vinifera | 709 | 17 | 3.63 ± 0.72 | 56 | 1 |

Spot number corresponds to the 2-DE imagines in Figures 2C,D. NMP means the number of peptides. Ratio means the ratio of B-toxic roots to controls and the values were the means ± SE of three replicates. Covered sequence (%) means the ratio of the number of amino acids of the matched peptides to the number of amino acids of the full-length protein. Proteins shared by C. sinensis and C. grandis roots were marked in bold.

Figure 4.

Classification of B-toxicity-responsive protein spots in C. grandis (A), C. sinensis (B) roots, and venn diagram analysis of B-toxicity-responsive protein spots in citrus roots (C).

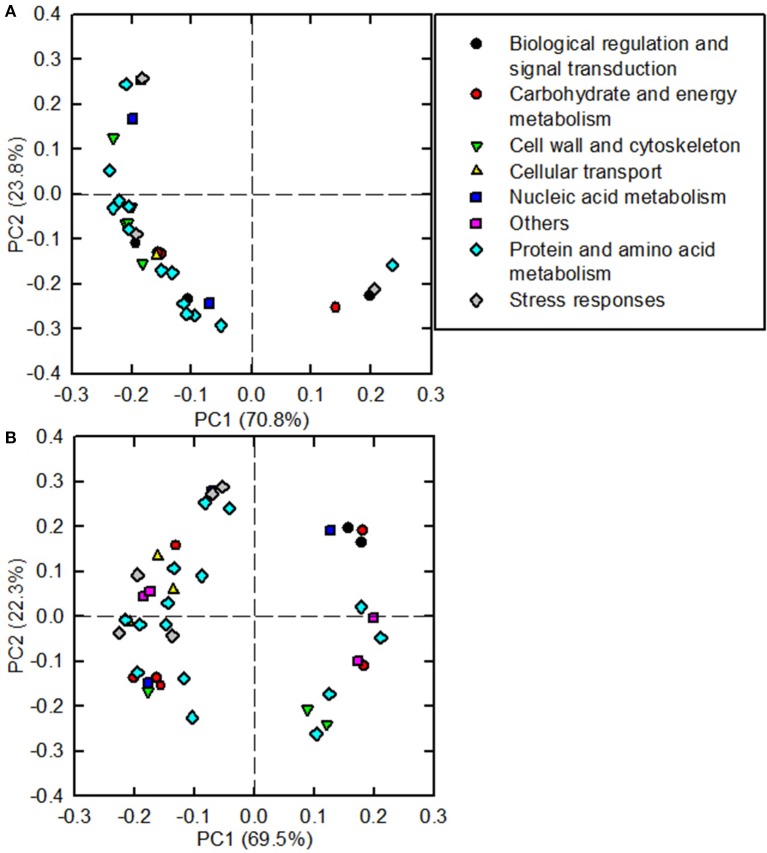

Principal component analysis loading plots of DAPs

As shown in Figure 5, 31 and 41 B-toxicity-responsive proteins identified in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots were submitted to PCA procedure. The first two components accounted for 94.6% (70.8% for PC1 and 23.8% for PC2) and 91.8% (69.5% for PC1 and 22.3% for PC2) of total variation in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, respectively. The DAPs involved in protein and amino acid metabolism and cell wall and cytoskeleton were highly clustered in C. sinensis roots. In contrast, no obvious clustered proteins were observed in C. grandis roots.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) loading plots of differentially abundant proteins in B-toxic C. sinensis (A) and C. grandis (B) roots.

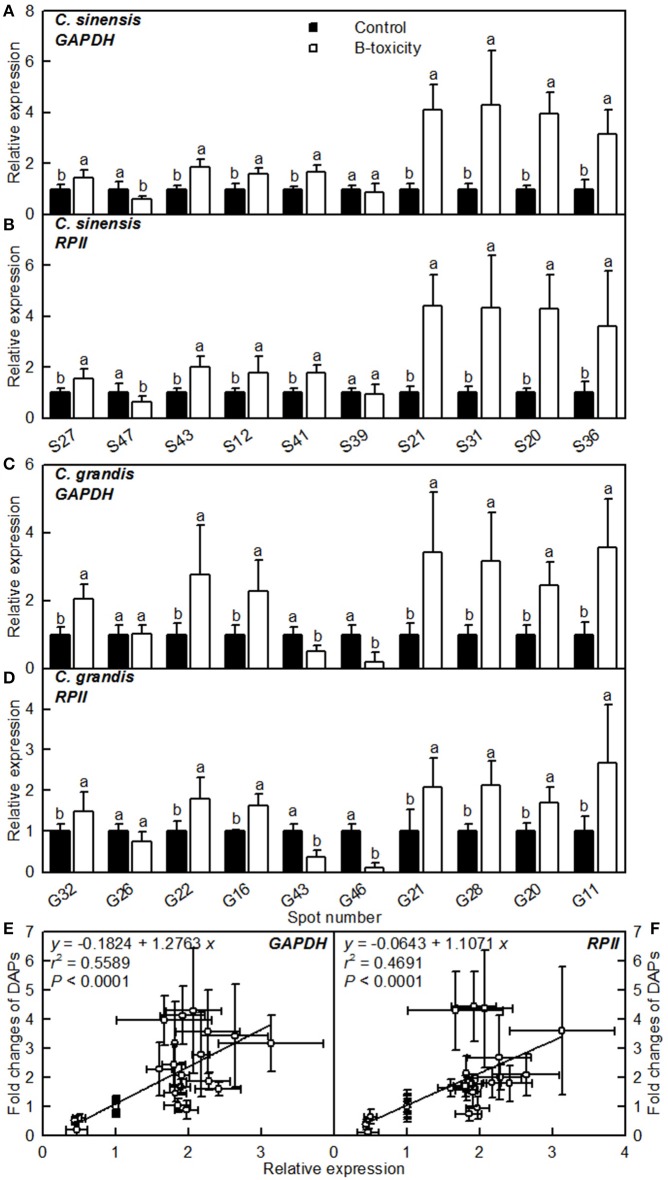

qRT-PCR analysis of genes for DAPs

The mRNA levels of genes encoding 20 B-toxicity-responsive proteins from C. sinensis (S27, 47, 43, 12, 41, 39, 13, 31, 20, and 36) and C. grandis (G32, 26, 22, 16, 43, 46, 21, 28, 20, and 11) roots (Figures 6A–D) were assayed in order to examine the relationship between the abundances of proteins and the expression levels of genes. The expression levels of all genes except for S39 and G26 matched well with our 2-DE data (Tables 2, 3) regardless of which internal standard was used to calculate the relative expression levels, suggesting that most of B-toxicity-responsive proteins were regulated at the transcriptional level. This is also supported by our analysis that the qRT-PCR data and the 2-DE results were significantly and positively correlated (Figures 6E,F).

Figure 6.

Relative expression levels of genes encoding 20 B-toxicity-responsive proteins from C. sinensis (A,B) and C. grandis (C,D) roots using GAPDH (A,C) and RPII (B,D) as internal standards, and the correlation analysis of qRT-PCR results and 2-DE data (E,F). For (A–D), bars represent means ± SD (n = 3); Significant tests between two means were performed by unpaired t-test; Different letters above the bars indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05. For (E,F), 2-DA data from Tables 2, 3.

Proteins related to carbohydrate and energy metabolism

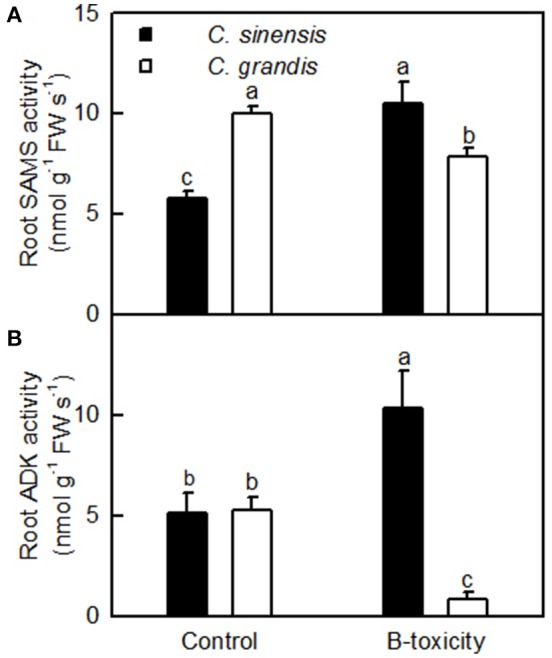

ADK plays key roles in the maintenance of purine nucleotide pools and in the active methyl cycle (Moffatt et al., 2002; Kettles et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015). Schoor et al. (2011) observed that silencing of ADK in Arabidopsis caused impaired root growth, small, crinkled rosette leaves, and decreased apical dominance accompanied by an increased concentration of active cytokinin (CK) ribosides, concluding that ADK was responsible for CK homeostasis in vivo. We found that the abundances of ADK2 (S27) and ADK isoform 1T-like protein (S28) were increased in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, while only one down-accumulated ADK isoform 1T-like protein (G24) was identified in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Tables 2, 3). Similarly, B-toxicity increased the abundances of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 2 [also known as S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase 2 (SAMS2); S41] involved in the formation of SAM from methionine and ATP, and 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase (also known as methionine synthase; S39) involved in the biosynthesis of methionine in C. sinensis roots and SAMS (G44) in C. grandis roots, and decreased the abundances of two SAMS1 family protein (G33 and 43) in C. grandis roots (Tables 2, 3). In addition, the activities of both SAMS and ADK were increased in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, but decreased in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Figure 7). Therefore, the active methyl cycle might be upregulated in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, but downregulated in B-toxic C. grandis roots. This agrees with the report that the active methyl cycle was induced by drought in drought-resistant rice leaves, but inhibited in drought sensitive rice leaves, and that the cycle played a role in rice drought resistance (Zhang et al., 2012). It is known that SAM not only plays a role in the active methyl cycle but also serves as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of polyamines (PAs) and ethylene (Ravanel et al., 1998). Hassan et al. (2010) reported that the expression of genes encoding SAM decarboxylase [SAMDC, a key enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of PAs (spermidine and spermine)], methinnine synthase 1 and SAMS2 was upregulated in B-tolerant Sahara barley roots, and that an antioxidant mechanisms involving PAs and water-water cycle in Sahara barley might play a role in tolerating high level of soil B. Hassan et al. (2010) also suggested that increased activity of SAMDC on SAM might inhibit ethylene production, hence reducing leaf senescence in Sahara barley. Evidence shows that transgenic plants with elevated levels of PAs have enhanced tolerance to different abiotic stresses (Alcázar et al., 2006). Recently, Tanou et al. (2014) observed that exogenous PAs partially alleviated the NaCl-induced phenotypic and physiological impairments in citrus plants, and systematically upregulated the expression of genes involved in PA biosynthesis (arginine decarboxylase, SAMDC, spermidine synthase, and spermine synthase) and catabolism (diamine oxidase and polyamine oxidase). Also, PAs reprogrammed the oxidative status in salt-stressed citrus plants. Based on these results, we concluded that the B-toxicity-induced upregulation of the active methyl cycle might play a role in the B-tolerance of C. sinensis via enhancing the biosynthesis of PAs.

Figure 7.

Effects of B-toxicity on the activities of SAMS (A) and ADK (B) in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots.Bars represent means ± SD (n = 4). Differences among four treatments were analyzed by two (species) × two (B levels) ANOVA. Different letters above the bars indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05.

We found that the abundances of all the four B-toxicity-responsive proteins involved in glycolysis (G22, 42, and 51) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (G50) were increased in C. grandis roots and that ATP synthase subunit α (G46) was down-accumulated in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Table 3). Thus, ATP synthase-mediated ATP biosynthesis might be decreased in these roots. This might contribute to the maintenance of ATP balance, when the production of ATP was increased due to upregulated glycolysis and TCA cycle and the consumption of ATP was decreased due to decreased activities of ADK and SAMS. However, the abundance of malate dehydrogenase (MDH, S47) involved in TCA cycle was decreased in B-toxic C. sinensis roots (Table 2).

Stress response-related proteins

Because the production of ROS (H2O2) was increased in B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis roots, especially in the former (Figure 1E), antioxidant enzymes might be induced in these roots. As expected, the abundance of Cu/Zn-SOD (G32) was increased in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Table 3). Besides antioxidant enzymes, the abundance of lactoylglutathione lyase (LGL; G26) was augmented in B-toxic C. grandis roots. In addition to the detoxification of methylglyoxal, a cytotoxic compound formed spontaneously from the glycolysis and photosynthesis intermediates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, LGL also play a role in oxidative stress tolerance (Yadav et al., 2005). The increased abundance of LGL agrees with our data that the abundances of four protein species involved in glycolysis (G22, 42, and 51) and TCA cycle (G50) were elevated in B-toxic C. grandis roots. By contrast, we only obtained one up-accumulated late-embryogenesis abundant protein 2 (LEA-2; S17) from B-toxic C. sinensis roots (Tables 2, 3). To conclude, more proteins related to detoxification were up-accumulated in B-toxic C. grandis roots than in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, which agrees with the increased requirement for detoxification of the more ROS and other toxic compounds such as aldehydes in the former because the production of ROS was higher in B-toxic C. grandis than in B-toxic C. sinensis roots (Figure 1E). We found that the level of MDA did not differ between B-toxic roots and controls (Figure 1C), demonstrating that the upregulation of antioxidant system provided sufficient protection to B-toxic roots against oxidative damage.

Proteins related to cell wall and cytoskeleton

All of the identified DAPs in cytokeleton were up-accumulated in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, while we isolated two down-accumulated proteins in cytokeleton (actin 1, G34) and polysaccharide biosynthesis (α-1,4-glucan-protein synthase 1; G52), and one up-accumulated α-tubulin in cytokeleton (G25) from B-toxic C. grandis roots (Tables 2, 3). Thus, C. sinensis roots might have a better capacity to keep cytoskeleton and cell wall integrity than C. grandis roots under B-toxicity, which might be responsible for the higher B-tolerance of the former. Similar results have been obtained on B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015).

Proteins related to protein, amino acid, and nucleic acid metabolisms

Proteasomes are responsible for the degradation of the inactive and futile proteins. Most of proteins degraded by proteasomes are first tagged by ubiquitin (Kurepa and Smalle, 2008). We obtained two up-accumulated proteasomes (G6 and 13) and two up-accumulated ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (G48 and 54) from B-toxic C. grandis roots, but only one up-accumulated proteasome (S9) from B-toxic C. sinensis (Tables 2, 3), demonstrating that B-toxicity accelerated proteolysis, especially in the former. This agrees with our data that B-toxicity only decreased total soluble protein concentration in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Guo et al., 2016). B-toxicity-induced increase in protein degradation implies that misfolded and damaged proteins were increased in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, especially in the latter. In addition, we identified one up-accumulated α chain of nascent polypeptide associated complex (α-NAC, S8) from B-toxic C. sinensis roots. NAC, including α and β subunits, plays a role in protecting newly synthesized polypeptides on ribosome from proteolysis and in facilitating its folding (Karan and Subudhi, 2012; Kogan and Gvozdev, 2014). Thus, the up-accumulation of α-NAC in B-toxic C. sinensis might alleviate B-toxicity induced protein degradation and misfolding, hence preventing the reduction of proteins. All B-toxicity-responsive proteins (S23, 40, and 36, and G7, 40, 11, and 41) in protein biosynthesis were up-accumulated in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots except for eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (S34 and G30) (Tables 2, 3). Therefore, the lower level of total soluble proteins in B-toxic C. grandis roots might be mainly caused by increased proteolysis rather than by decreased biosynthesis.

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 7A, the abundances of the five DAPs (S43, 41, 39, 42, and 31) involved in amino acid metabolism and the activity of SAMS were increased in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, suggesting that the biosynthesis of some amino acids might be enhanced in these roots. SAM is an allosteric activator of threonine synthase (TS), which is involved in the biosynthesis of branched chain amino acids (BCAAs, valine, leucine and isoleucine; Curien et al., 1998; Ravanel et al., 1998). Thus, TS might be activated in B-toxic C. sinensis roots due to increased SAM biosynthesis resulting from enhanced SAMS activity. Zeh et al. (2001) found that antisense inhibition of TS led to increased level of methionine in transgenic potato plants because of the redirection of carbon flow from the threonine to the methionine branch. Ketol-acid reductoisomerase (KARI) is involved in BCAA biosynthesis. Kochevenko and Fernie (2011) reported that the concentrations of BCAAs in the leaves of transgenic tomato line 7, in which the KARI transcript level was remained at about 70% of the wildtype level, were not lower than in the wildtype leaves, whereas BCAA levels in the leaves of transgenic lines 3 and 6, in which the expression level of KARI was decreased to 27% of the wild-type level, were only 49–79% of the wildtype leaves. Thus, the levels of BCAAs might be enhanced in B-toxic C. sinensis roots due to the activation of TS resulting from increased SAMS activity (Figure 7A) and the increased abundances of KARI (Table 2). However, we obtained two down-accumulated SAMS1 (G33 and 43), one up-accumulated SAMS (G44), and two up-accumulated KARI spots (G27 and 28) from B-toxic C. grandis roots. In addition, SAMS activity was reduced in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Figure 7A). Based on these results, we concluded that BCAA biosynthesis might be disturbed in these roots.

We observed that the abundances of glycine-rich RNA-binding protein (GR-RBP) in C. sinensis (S21) and C. grandis (G21) roots and GR-RBP4 in C. sinensis roots (S13) increased when exposed to B-toxicity (Tables 2, 3), which agrees with the reports that the transcript levels of the genes encoding GR-RBPs were increased in higher plants following exposure to various abiotic stresses (Sachetto-Martins et al., 2000; Kwak et al., 2005). DEAD box RNA helicases, which may actively disrupt misfolded RNA structures by utilizing energy produced from ATP hydrolysis so that correct folding can occur, play key roles in plant response to various stresses (Li et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2015). Thus, the down-accumulation of DEAD-box RNA helicase-like protein (G35) in B-toxic C. grandis roots might decrease C. grandis stress-tolerance, hence impairing its B-tolerance. However, the abundance of spliceosome RNA helicase BAT1 (G36) was increased in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Table 3).

Proteins related to cellular transport

The abundances of four protein spots involved in cellular transport were increased in B-toxic C. sinensis (S20) and C. grandis (G18, 20, and 54) roots (Tables 2, 3), as reported on B-toxic leaves of barley (Atik et al., 2011), C. sinensis and C. grandis (Sang et al., 2015). However, the mRNA levels of all 13 B-toxicity-responsive genes involved in cellular transport were downregulated in C. grandis and C. sinensis roots except for one upregulated H+-ATPase 4 (Guo et al., 2016). The difference between protein abundances and gene expression levels implies that post-translational modifications (PTMs) might affect protein levels. Atik et al. (2011) observed that heterologous expression of a gene encoding V-ATPase subunit E, a protein induced by B-toxicity in barley leaves, conferred yeast B-tolerance. The up-accumulation of V-ATPase B subunit (S20, and G18 and 20) in the two citrus species might be an adaptive response to B-toxicity by providing energy for compartmentation of excess B in vacuoles (Alemzadeh et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011). Klychnikov et al. (2007) showed that plant V-ATPase could interact with 14-3-3 proteins. The up-accumulation of V-ATPase B subunit in B-toxic C. sinensis roots agrees with our data that the abundance of 14-3-3 family protein (S14) was increased in these roots. However, the abundance of 14-3-3-like protein GF14 phi (G9 and 10) was decreased in B-toxic C. grandis roots, implying that other factors was involved in the regulation of V-ATPase B subunit.

Proteins related to biological regulation and signal transduction

B-toxicity increased the abundance of nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 (NDPK1; S44) and 14-3-3 family protein (S14) in C. sinensis roots (Table 2), as observed on B-toxic C. sinensis leaves (Sang et al., 2015). However, the abundances of 14-3-3-like protein GF14 phi (G9 and 10) were reduced in B-toxic C. grandis roots (Table 3). Fukamatsu et al. (2003) demonstrated that Arabidopsis NDPK1 played a role in ROS response by interacting with three CATs. Overexpression of NDPKs conferred enhanced tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in potato, alfalfa and poplar (Fukamatsu et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2014). 14-3-3 proteins, the master regulators of many signal transduction cascades, have a key role in stress-tolerance in higher plants (Chen et al., 2006). Transgenic potato plants overexpressing 14-3-3 protein genes displayed delayed leaf senescence and enhanced antioxidant activity, while transgenic potato plants with antisense 14-3-3 protein genes displayed early leaf senescence (Wilczynski et al., 1998; Lukaszewicz et al., 2002). Thus, the B-toxicity-induced up-accumulation of NDPK1 and 14-3-3 might contribute to the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis.

Comparison of B-toxicity-responsive proteins between roots and leaves

More B-toxicity-responsive proteins were identified in C. grandis (41) roots than in C. sinensis (31) roots (Tables 2, 3), while Sang et al. (2015) identified 45 and 55 DAPs from B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis leaves, respectively. As shown in Tables 2, 3 and Figures 4A,B, we identified more up-accumulated proteins than down-accumulated proteins in B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis roots, especially in B-toxic C. sinensis roots, but the reverse was the case in B-toxic C. grandis leaves although the number of up-accumulated proteins (27) in B-toxic C. sinensis leaves was slightly higher than that of down-accumulated proteins (23) (Sang et al., 2015). Furthermore, the vast majority of B-toxicity-responsive proteins were identified only in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots or leaves, only three proteins with the same accession No. were shared by C. grandis roots and leaves (Table 4). In addition, many other differences existed in B-toxicity-responsive proteins between roots and leaves of the two citrus species. For examples, the carbohydrate and energy metabolism-related proteins was the largest category of the B-toxicity-responsive proteins in C. sinensis and C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015). Similar result has been obtained on NaCl-stressed Citrus aurantium leaves (Tanou et al., 2009). However, the protein and amino acid metabolism-related proteins was the most abundant category of B-toxicity-responsive proteins in C. sinensis and C. grandis roots (Tables 2, 3). In the previous study, we isolated similar up- (11) and down-accumulated (9) carbohydrate and energy metabolism-related proteins in B-toxic C. sinensis leaves, and more down- (16) than up-accumulated (9) proteins in B-toxic C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015). However, more up- than down-accumulated proteins involved in carbohydrate and energy metabolism were identified in B-toxic C. sinensis (two up- and one down-accumulated) and C. grandis (four up- and two down-accumulated) roots (Tables 2, 3). As shown in Table 3, all four DAPs related to glycolysis (G22, 42, and 51) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (G50) were up-accumulated, and ATP synthase subunit α (G46) involved in ATP was decreased in B-toxic C. grandis roots. By contrast, we isolated four down- and three up-accumulated proteins in glycolysis and TCA cycle and one up-accumulated mitochondrial ATP synthase in B-toxic C. grandis leaves (Sang et al., 2015). In B-toxic C. sinensis leaves, we obtained three up-accumulated malate dehydrogenases (MDHs), while only one down-accumulated MDH (S47) was detected in B-toxic C. sinensis roots (Table 2). Thus, the adaptive responses of carbohydrate and energy metabolism-related proteins to B-toxicity differed between roots and leaves of the two citrus species.

Table 4.

B-toxicity-responsive proteins shared by roots and leaves.

| Protein identity | Accession No. | Fold change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. grandis | C. sinensis | ||||

| Roots | Leaves | Roots | Leaves | ||

| Proteasome subunit α type, putative | gi|255584432 | 1.77 | 1.98 | 1.76 | |

| V-ATPase B subunit | gi|4519264 | 1.80 (G18) 1.80 (G20) | 1.67 | 2.85 | |

| Triosphosphate isomerase-like protein | gi|76573375 | 2.02 | 0.14 | ||

| Cu/Zn-SOD | gi|2274917 | 1.91 | 2.99 | ||

| S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 4 | gi|222861722 | 0.43 (G33) 0.44 (G43) | 1.63 | ||

B-toxicity increased the abundances of proteins involved in protein degradation, and decreased the abundances of proteins related to protein biosynthesis in C. grandis and C. sinensis leaves (Sang et al., 2015). By contrast, the abundances of the two kinds of proteins were enhanced in B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis roots (Tables 2, 3). Interestingly, total soluble protein level was reduced only in B-toxic C. grandis roots and leaves (Sang et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2016). Thus, the causes for the decrease of total soluble proteins in B-toxic C. grandis roots and leaves were different.

We isolated seven up-accumulated, and one down- and three up-accumulated proteins involved in antioxidation and detoxification from B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis leaves, respectively (Sang et al., 2015), and two up-accumulated (G32 and 26) and one up-accumulated (S17) from B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis roots, respectively (Tables 2, 3). However, MDA concentration was increased only in B-toxic C. grandis leaves (Figures 1G,H). This might be related to the findings that B mainly accumulated in B-toxic C. grandis and C. sinensis leaves (Figures 1G,H; Jiang et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2014), and that the increased requirement for the detoxification of ROS and other toxic compounds such as reactive aldehtdes was greater in B-toxic C. grandis leaves than in B-toxic C. sinensis leaves (Sang et al., 2015).

To conclude, B-toxicity-induced alterations of protein profiles greatly differed between roots and leaves of the two citrus species.

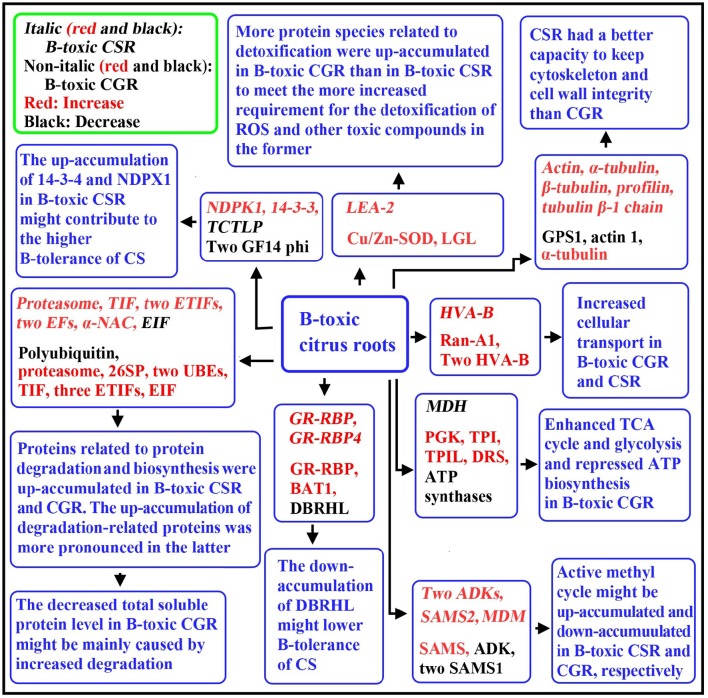

Conclusions

Using a 2-DE based MS approach, we comparatively investigated the effects of B-toxicity on DAPs in roots of two citrus species with different B-tolerance and obtained 27 up- and four down-accumulated, and 28 up- and 13 down-accumulated proteins from B-toxic C. sinensis and C. grandis) roots, respectively. Most of B-toxicity-responsive proteins only were isolated from C. sinensis or C. grandis roots, only nine proteins were shared by the both. Great differences existed in B-toxicity-induced alterations of protein profiles between C. sinensis or C. grandis roots. Based on our findings, a diagram for the responses of C. grandis and C. sinensis roots to B-toxicity was presented in Figure 8. The higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis might be associated with (a) the B-toxicity-induced upregulation of the active methyl cycle and (b) the better performance in maintaining cell wall and cytoskeleton integrity. In addition, proteins related to nucleic acid metabolism, biological regulation and signal transduction might play a role in the higher B-tolerance of C. sinensis. To conclude, our findings provided some novel cues on the molecular mechanisms of citrus B-toxicity and B-tolerance.

Figure 8.

A diagram for the responses of C. grandis and C. sinensis roots to B-toxicity. CG, C. grandis; CGR, C. grandis roots; CS, C. sinensis; CSR, C. sinensis roots; DBRHL, DEAD-box RNA helicase-like protein; DRS, dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex; EF, elongation factor; EIF, eukaryotic initiation factor; ETIF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor; GPS1, α-1,4-glucan-protein synthase 1; MDM, 5-methyltetrahy dropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase; PGK, Phosphoglycerate kinase; 26SP, 26S proteasome subunit RPN12; TIF, translation initiation factor; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase; TPIL, triosphosphate isomerase-like protein; UBE, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; VHA-B, Vacuolar H+-ATPase B subunit.

Data access

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD004050.

Author contributions

WS and ZH contributed equally to this works. WS carried most of the experiment and analyzed the data; ZH drafted the manuscript; LY participated in the direction of this study; PG performed the qRT-PCR analysis; XY participated in the analysis of B; LC designed and directed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Grant of China (No. 31301740), the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS27) and the Provincial Natural Science Grant of Fujian, China (No. 2014J05033).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00180/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alcázar R., Marco F., Cuevas J. C., Patron M., Ferrando A., Carrasco P., et al. (2006). Involvement of polyamines in plant response to abiotic stress. Biotechnol. Lett. 28, 1867–1876. 10.1007/s10529-006-9179-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemzadeh A., Fujie M., Usami S., Yoshizaki T., Oyama K., Kawabata T., et al. (2006). ZMVHA-B1, the gene for subunit B of vacuolar H+-ATPase from the eelgrass Zostera marina L. is able to replace vma2 in a yeast null mutant. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 102, 390–395. 10.1263/jbb.102.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardic M., Sekmen A. H., Turkan I., Tokur S., Ozdemir F. (2009). The effects of boron toxicity on root antioxidant systems of two chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars. Plant Soil 314, 99–108. 10.1007/s11104-008-9709-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atik A. E., Bozdağ G. O., Akinci E., Kaya A., Koc A., Yalcin T., et al. (2011). Proteomic changes during boron tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare) and the role of vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase subunit E. Turk. J. Bot. 35, 379–388. 10.3906/bot-1007-29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Gal A., Shani U. (2003). Water use and yield of tomatoes under limited water and excess boron. Plant Soil 256, 179–186. 10.1023/A:1026229612263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins D. G., Lukaszewski K. M. (1998). Boron in plant structure and function. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 481–500. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram and quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Cristóbal J. J., Rexach J., González-Fontes A. (2008). Boron in plants: deficiency and toxicity. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 1247–1255. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervilla L. M., Blasco B., Ríos J. J., Romero L., Ruiz J. M. (2007). Oxidative stress and antioxidants in tomato (Sola um lycopericum) plants subjected to boron toxicity. Ann. Bot. 100, 747–756. 10.1093/aob/mcm156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H. D. (1968). The mineral nutrition of citrus, in The Citrus Industry, Vol. 2, eds Reuther W., Webber H. J., Batchelor L. D.(California, CA: Division of Agricultural Sciences, University of California; ), 127–189. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. M., Eckert R. L. (1977). Phosphorylation of cytokinin by adenosine kinase from wheat germ. Plant Physiol. 59, 443–447. 10.1104/pp.59.3.443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Song Y., Zhuang K., Li L., Xia Y., Shen Z. (2015). Proteomic analysis of copper-binding proteins in excess copper-stressed roots of two rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties with different Cu tolerances. PLoS ONE 10:e0125367. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Li Q., Sun L., He Z. (2006). The rice 14-3-3 gene family and its involvement in responses to biotic and abiotic stress. DNA Res. 13, 53–63. 10.1093/dnares/dsl001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. S., Han S., Qi Y. P., Yang L. T. (2012). Boron stresses and tolerance in citrus. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11, 5961–5969. 10.5897/AJBX11.073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. S., Qi Y. P., Liu X. H. (2005). Effects of aluminum on light energy utilization and photoprotective systems in citrus leaves. Ann. Bot. 96, 35–41. 10.1093/aob/mci145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curien G., Job D., Douce R., Dumas R. (1998). Allosteric activation of Arabidopsis threonine synthase by S-adenosylmethionine. Biochemistry 37, 13212–13221. 10.1021/bi980068f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiray H., Dereboylu A. E., Altan F., Zeytünlüoğlu A. (2011). Identification of proteins involved in excess boron stress in roots of carrot (Daucus carota L.) and role of niacin in the protein profiles. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 15545–15551. 10.5897/AJB11.1117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton F. M. (1935). Boron in soils and irrigation waters and its effect upon plants, with particular reference to the San Joaquin Valley of California. U.S. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bull. 448, 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal S., Genc E., Karaman A., Khosroushahi F. K., Kizilkaya M., Demir Y., et al. (2014). Differential responses of two wheat varieties to increasing boron toxicity. Changes on antioxidant activity, oxidative damage and DNA profile. J. Environ. Protect. Ecol. 15, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Fukamatsu Y., Yabe N., Hasunuma K. (2003). Arabidopsis NDK1 is a component of ROS signaling by interacting with three catalases. Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 982–989. 10.1093/pcp/pcg140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Qi Y. P., Yang L. T., Ye X., Huang J. H., Chen L. S. (2016). Long-term boron-excess-induced alterations of gene profiles in roots of two citrus species differing in boron-tolerance revealed by cDNA-AFLP. Front. Plant Sci. 7:898. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Qi Y. P., Yang L. T., Ye X., Jiang H. X., Huang J. H., et al. (2014). cDNA-AFLP analysis reveals the adaptive responses of citrus to long-term boron-toxicity. BMC Plant Biol. 14:284. 10.1186/s12870-014-0284-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Tang N., Jiang H. X., Yang L. T., Li Y., Chen L. S. (2009). CO2 assimilation, photosystem II photochemistry, carbohydrate metabolism and antioxidant system of Citrus leaves in response to boron stress. Plant Sci. 176, 143–153. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M., Oldach K., Baumann U., Langridge P., Sutton T. (2010). Genes mapping to boron tolerance QTL in barley identified by suppression subtractive hybridization. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 188–198. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges D. M., DeLong J. M., Forney C. F., Prange R. K. (1999). Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 207, 604–611. 10.1007/s004250050524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. H., Cai Z. J., Wen S. X., Guo P., Ye X., Lin G. Z., et al. (2014). Effects of boron toxicity on root and leaf anatomy in two citrus species differing in boron tolerance. Trees Struct. Funct. 28, 1653–1666. 10.1007/s00468-014-1075-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. H., Qi Y. P., Wen S. X., Guo P., Chen X. M., Chen L. S. (2016). Illumina microRNA profiles reveal the involvement of miR397a in citrus adaptation to long-term boron toxicity via modulating secondary cell-wall biosynthesis. Sci. Rep. 6:22900. 10.1038/srep22900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. X., Tang N., Zheng J. G., Chen L. S. (2009). Antagonistic actions of boron against inhibitory effects of aluminum toxicity on growth, CO2 assimilation, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, and photosynthetic electron transport probed by the JIP-test, of Citrus grandis seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 9:102. 10.1186/1471-2229-9-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L. F., Liu Y. Z., Yin X. X., Peng S. A. (2016). Transcript analysis of citrus miRNA397 and its target LAC7 reveals a possible role in response to boron toxicity. Acta Physiol. Plant. 38, 18 10.1007/s11738-015-2035-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karan R., Subudhi P. K. (2012). Overexpression of a nascent polypeptide associated complex gene (SaβNAC) of Spartina alterniflora improves tolerance to salinity and drought in transgenic Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 424, 747–752. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettles N. L., Kopriva S., Malin G. (2014). Insights into the regulation of DMSP synthesis in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana through APR activity, proteomics and gene expression analyses on cells acclimating to changes in salinity, light and nitrogen. PLoS ONE 9:e94795. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Balcezak T. J., Nathin S. J., McMullen H. F., Hansen D. E. (1992). The use of a spectrophotometric assay to study the interaction of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase with methionine analogues. Anal. Biochem. 207, 68–72. 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90501-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klychnikov O. I., Li K. W., Lill H., de Boer A. H. (2007). The V-ATPase from etiolated barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) shoots is activated by blue light and interacts with 14-3-3 proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 1013–1023. 10.1093/jxb/erl261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochevenko A., Fernie A. R. (2011). The genetic architecture of branched-chain amino acid accumulation in tomato fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 3895–3906. 10.1093/jxb/err091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan G. L., Gvozdev V. A. (2014). Multifunctional nascent polypeptide-associated complex (NAC). Mol. Biol. 48, 189–196. 10.1134/S0026893314020095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konsaeng S., Dell B., Rerkasen B. (2005). A survey of woody tropical species for boron retranslocation. Plant Prod. Sci. 8, 338–341. 10.1626/pps.8.338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa J., Smalle J. A. (2008). Structure, function and regulation of plant proteasomes. Biochimie 90, 324–335. 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K. J., Kim Y. O., Kang H. (2005). Characterization of transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GR-RBP4 under high salinity, dehydration, or cold stress. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3007–3016. 10.1093/jxb/eri298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Bae D. W., Kim S. H., Han H. J., Liu X., Park H. C., et al. (2010). Comparative proteomic analysis of the short-term responses of rice roots and leaves to cadmium. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 161–168. 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Liu H., Zhang H., Wang X., Song F. (2008). OsBIRH1, a DEAD-box RNA helicase with functions in modulating defence responses against pathogen infection and oxidative stress. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2133–2146. 10.1093/jxb/ern072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Han M. Q., Lin F., Ten Y., Lin J., Zhu D. H., et al. (2015). Soil chemical properties, ‘Guanximiyou’ pummelo leaf mineral nutrient status and fruit quality in the southern region of Fujian province, China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 15, 615–628. 10.4067/s0718-95162015005000029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg B., Klenow H., Hansen K. (1967). Some properties of partially purified mammalian adenosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewicz M., Matysiak-Kata I., Aksamit A., Szopa J. (2002). 14-3-3 protein regulation of the antioxidant capacity of transgenic potato tubers. Plant Sci. 163, 125–130. 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00081-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia K. V., Kent J. T., Bibby J. M. (1979). Multivariate Analysis. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt B. A., Stevens Y. Y., Allen M. S., Snider J. D., Pereira L. A., Todorova M. I., et al. (2002). Adenosine kinase deficiency is associated with developmental abnormalities and reduced transmethylation. Plant Physiol. 128, 812–821. 10.1104/pp.010880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis I. E., Dimassi K. N., Bosabalidis A. M., Therios I. N., Patakas A., Giannakoula A. (2004). Boron toxicity in ‘Clementine’ mandarin plants grafted on two rootstocks. Plant Sci. 166, 539–547. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.10.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H. Y., Qi Y. P., Lee J., Yang L. T., Guo P., Jiang H. X., et al. (2015). Proteomic analysis of Citrus sinensis roots and leaves in response to long-term magnesium-deficiency. BMC Genomics 16:253. 10.1186/s12864-015-1462-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanel S., Gakière B., Job D., Douce R. (1998). The specific features of methionine biosynthesis and metabolism in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7805–7812. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachetto-Martins G., Franco L. O., de Oliveira D. E. (2000). Plant glycine-rich proteins: a family or just proteins with a common motif? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1492, 1–14. 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang W., Huang Z. R., Qi Y. P., Yang L. T., Guo P., Chen L. S. (2015). An investigation of boron-toxicity in leaves of two citrus species differing in boron-tolerance using comparative proteomics. J. Proteomics 123, 128–146. 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoor S., Farrow S., Blaschke H., Lee S., Perry G., von Schwartzenberg K., et al. (2011). Adenosine kinase contributes to cytokinin interconversion in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 659–672. 10.1104/pp.111.181560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B., Li C., Tarczynski M. C. (2002). High free-methionine and decreased lignin content result from a mutation in the Arabidopsis S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase 3 gene. Plant J. 29, 371–380. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng O., Zhou G., Wei Q., Peng S., Deng X. (2010). Effects of excess boron on growth, gas exchange, and boron status of four orange scion-rootstock combinations. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 173, 469–476. 10.1002/jpln.200800273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Uribe E. G., Ball E., Heuer S., Lüttge U. (1984). Characterization of the vacuolar ATPase activity of the crassulacean-acid-metabolism plant Kalanchoë daigremontiana receptor modulating. Eur. J. Biochem. 141, 415–420. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. E., Grattan S. R., Grieve C. M., Poss J. A., Läuchli A. E., Suarez D. L. (2013). pH dependent salinity-boron interactions impact yield, biomass, evapotranspiration and boron uptake in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.). Plant Soil 370, 541–554. 10.1007/s11104-013-1653-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Kim M. D., Yang K. S., Kwon S. Y., Kim S. H., Kim J. S., et al. (2008). Enhanced tolerance of transgenic potato plants overexpressing nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2 against multiple environmental stresses. Transgenic Res. 17, 705–715. 10.1007/s11248-007-9155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanou G., Job C., Rajjou L., Arc E., Belghazi M., Diamantidis G., et al. (2009). Proteomics reveals the overlapping roles of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in the acclimation of citrus plants to salinity. Plant J. 60, 795–804. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanou G., Ziogas V., Belghazi M., Christou A., Filippou P., Job D., et al. (2014). Polyamines reprogram oxidative and nitrosative status and the proteome of citrus plants exposed to salinity stress. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 864–885. 10.1111/pce.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Nakazato T., Sakanishi K., Yamada O., Tao H., Saito I. (2006). Single-step microwave digestion with HNO3 alone for determination of trace elements in coal by ICP spectrometry. Talanta 68, 1584–1590. 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., He X., Zhao Y., Shen Y., Huang Z. (2011). Wheat vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit B cloning and its involvement in salt tolerance. Planta 234, 1–7. 10.1007/s00425-011-1383-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Li H., Ke Q., Jeong J. C., Lee H. S., Xu B., et al. (2014). Transgenic alfalfa plants expressing AtNDPK2 exhibit increased growth and tolerance to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 84, 67–77. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warington K. (1923). The effect of boric acid and borax on the broad bean and certain other plants. Ann. Bot. 37, 629–672. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski G., Kulma A., Szopa J. (1998). The expression of 14-3-3 isoforms in potato is developmentally regulated. J. Plant Physiol. 153, 118–126. 10.1016/S0176-1617(98)80054-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S. K., Singla-Pareek S. L., Reddy M. K., Sopory S. K. (2005). Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing glyoxalase enzymes resist an increase in methylglyoxal and maintain higher reduced glutathione levels under salinity stress. FEBS Lett. 579, 6265–6271. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. T., Qi Y. P., Lu Y. B., Guo P., Sang W., Feng H., et al. (2013). iTRAQ protein profile analysis of Citrus sinensis roots in response to long-term boron-deficiency. J. Proteomics 93, 179–206. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You X., Yang L. T., Lu Y. B., Li H., Zhang S. Q., Chen L. S. (2014). Proteomic changes of citrus roots in response to long-term manganese toxicity. Trees Struct. Funct. 28, 1383–1399. 10.1007/s00468-014-1042-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeh M., Casazza A. P., Kreft O., Roessner U., Bieberich K., Willmitzer L., et al. (2001). Antisense inhibition of threonine synthase leads to high methionine content in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 127, 792–802. 10.1104/pp.010438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. L., Zhou J., Han Z., Shang Q., Wang Z. G., Gu X. H., et al. (2012). Active methyl cycle and transfer related gene expression in response to drought stress in rice leaves. Rice Sci. 19, 86–93. 10.1016/S1672-6308(12)60026-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C. P., Qi Y. P., You X., Yang L. T., Guo P., Ye X., et al. (2013). Leaf cDNA-AFLP analysis of two citrus species differing in manganese tolerance in response to long-term manganese-toxicity. BMC Genomics 14:621. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Chen G., Dong T., Wang L., Zhang J., Zhao Z., et al. (2015). SlDEAD31, a putative DEAD-Box RNA Helicase gene, regulates salt and drought tolerance and stress-related genes in tomato. PLoS ONE 10:e0133849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.