Abstract

Childhood primary angiitis of the central nervous system (cPACNS) is a rare and a potentially fatal cause of childhood stroke. The disease poses a diagnostic dilemma for the clinicians due to overlapping and varied clinical manifestations such as headache, focal acute neurological deficits, cognitive impairment, or encephalopathy. We report a young boy who presented with low-grade fever and headache but rapidly progressed to develop acute encephalopathy and quadriparesis with multiple cranial nerve palsies, masquerading as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. The neuroimaging was suggestive of vasculitis. He was diagnosed as cPACNS and recovered with immunosuppressive therapy.

Key words: Central nervous system vasculitis, childhood primary angiitis of the central nervous system, childhood stroke

Introduction

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) was identified as a distinct clinical entity in adults in 1959, and only recently now in children as a cause of childhood stroke.[1,2] The disease should be suspected in children presenting with newly acquired neurological or psychiatric deficits after exclusion of causes of secondary vasculitis.[3] The disease is a diagnostic challenge and is classified based on radiological findings. If detected and treated early, it responds well to immunosuppressant therapy.[3] We present a relapsing course of a young boy who was diagnosed as childhood PACNS (cPACNS) and was managed accordingly.

Case Report

A 6-year-old boy presented with low-grade fever and frontal headache off and on for last 1 month. Recently, he had developed right-sided torticollis but had no neurological deficits. There was no history of ear discharge, toothache, or head trauma. The child was conscious; ear, neck, and spine examination was normal. The central nervous system (CNS) examination revealed normal higher mental functions with palsy of right third cranial nerve and bilateral sixth cranial nerve. The motor and sensory systems were normal, and meningeal signs were absent. Investigations revealed normal hemoglobin and leukocyte count; C-reactive protein (CRP) was positive, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised 34 mm/1st h. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was normal. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine was also normal.

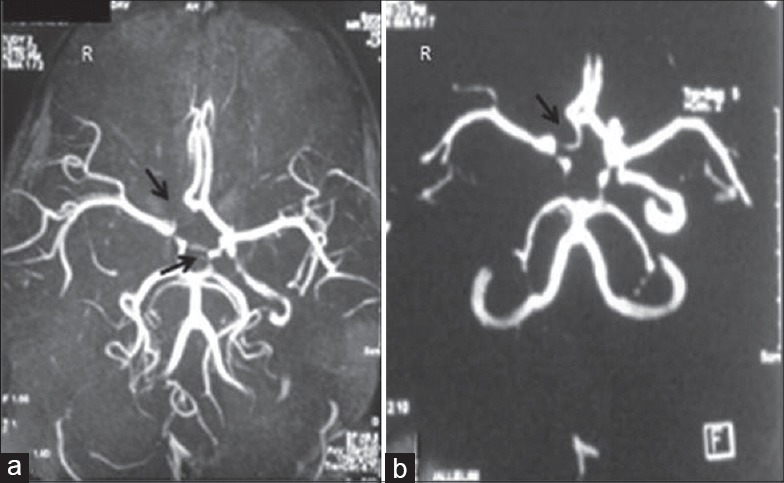

The patient deteriorated on day 3 of hospitalization with seizures, altered sensorium, quadriparesis, and left upper motor neuron seventh nerve palsy. A possibility of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis was suspected. The patient was started on pulse intravenous methylprednisolone. Repeat MRI-angiography (MRA) of the brain revealed block in the terminal right internal carotid artery (ICA), left ICA, and bilateral posterior communicating artery (PCA) suggestive of vasculitis with normal brain parenchyma and normal meninges [Figure 1a]. The workup for cause of vasculitis was noncontributory (Koch's workup, procoagulants, anti-nuclear antibody, lupus anticoagulant, and viral serology), and serum complement was normal. Echocardiography was normal, and there was no evidence of systemic vasculitis. Within 48 h of methylprednisolone, the patient regained sensorium with partial resolution of quadriparesis. A diagnosis of idiopathic CNS vasculitis was made, and the patient was started on oral prednisolone after five doses of methylprednisolone. The patient was discharged with residual deficit of bilateral squint (sixth nerve paresis) with a plan to continue steroids for 6 weeks.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography (a) initial scan: Occlusion in the terminal right internal carotid artery and bilateral posterior communicating artery; (b) follow-up after month: With thrombosis of the right internal carotid artery

The patient presented after 1 month with fresh left twelfth nerve palsy and residual bilateral sixth nerve paresis. Quadriparesis had resolved completely. There was no fever or any other neurological or psychiatric deficit. Repeat MRA of the brain revealed resolution of thrombosis and of thickening of the left ICA and bilateral PCA as compared to initial scan but persistent thrombosis of the right ICA [Figure 1b]. The ESR was 20 mm/1st h, and CRP was negative. The digital subtraction angiography of cranial vessels reported complete obliteration of right ICA distal to carotid bifurcation with good collateral formation; rest of brain vasculature was normal. The consent for diagnostic cranial vessel biopsy was declined by the family. A diagnosis of medium vessel PACNS (Mv-PACNS) was made. In light of partial response to steroids with features of steroid toxicity as evident on examination, the patient was shifted to azathioprine (steroid-sparing drug) as maintenance therapy. The patient is currently recovering and has mild residual right sixth nerve and left twelfth nerve paresis at 1 year of follow-up, with resolution of cushingoid features.

Discussion

Primary angiitis of CNS is a rare form of vasculitis with extremely low annual incidence of 2–4 cases per million patient-years.[4] Fewer cases are reported in childhood than adults.[5,6] The disease affects the small and medium size vessels of the brain resulting in lymphocytic infiltration of vessel walls with granulomatous differentiation (granulomas are absent in childhood forms).[4]

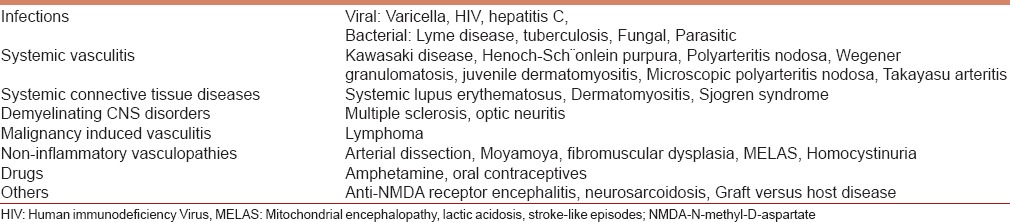

The diagnosis of PACNS is challenging because of rarity of disease, unexplained etiology, varied clinical presentation, and lack of sensitive and specific tests.[2,6] The diagnosis of PACNS should be suspected in any patient with multifocal or diffuse CNS involvement with a remitting or progressive course.[4,6] An acute systemic inflammatory response may be seen in few patients.[1,2] Laboratory tests which can exclude secondary causes of CNS vasculitis [as listed in Table 1] should be undertaken before establishing a diagnosis of PACNS. The acute phase reactants may be raised, and CSF abnormalities in the form of increased protein concentration or mild pleocytosis may be seen in majority though few studies have reported normal CSF findings.[6,7]

Table 1.

In CPACNS, two distinct patterns can be recognized – small vessel PACNS (Sv-PACNS) which presents with cognitive decline, seizures, and behavioral changes or Mv-PACNS where headache, hemiparesis, and other focal deficits are common manifestations.[8,9]

The gold standard for diagnosis is angiography which may reveal multiple “beading” or segmental narrowing in large, intermediate, or small arteries with interposed regions of ectasia or normal luminal architecture with collateral flow.[5,6] Brain biopsy was initially considered as gold standard but carries a mortality risk of 3.7%.[7] It may be difficult to detect Sv-PACNS by angiography, where diagnosis is confirmed with a brain biopsy.[4] The MRI with MRA of the brain is a noninvasive and safer alternative diagnostic modality with good sensitivity (90%–95%).[5,6] The abnormalities seen in subcortical white matter and deep gray matter are ischemic areas and infarcts with evidence of vasculitis.[6]

The diagnosis of PACNS is based on modified Calabrese and Mallek criteria which are a newly acquired focal or diffuse neurological or psychiatric symptom in a patient ≤18 years of age plus characteristic angiographic and/or histopathological features of CNS angiitis, in the absence of an underlying systemic disorder that explains or mimics the features.[3]

There are no standard treatment guidelines for PACNS.[2,4,6] The treatment of PACNS includes an induction phase and a maintenance phase. In general, high-dose corticosteroids are primarily used for rapid control of inflammation during induction.[8] Cyclophosphamide pulses for 3–6 months may be used in conjunction with steroids to induce remission, but myelosuppression should be anticipated. Safer alternatives such as azathioprine, mycophenolate, and methotrexate are given as maintenance therapy.[10] Mv-PACNS has a more benign course and fewer relapses as compared to Sv-PACNS where relapse may occur in 25%–30% patients. The diagnosis of relapse rests on clinical presentation and supportive radiography; acute phase reactants have little role.[7] Thus, patients with Sv-PACNS need to be monitored for long and require immunosuppressive therapy for longer period (5 years) as compared to Mv-PACNS where maintenance therapy for 2–3 years suffices.[7,10]

Conclusion

PACNS is a challenge to diagnose and treat. Early identification of this condition helps to initiate appropriate immunosuppressive therapy which reduces chances of complications and mortality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the technical support of the Department of Neurosurgery, G. B. Pant Hospital, New Delhi, India.

References

- 1.Cellucci T, Benseler SM. Central nervous system vasculitis in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:590–7. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833c723d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cellucci T, Benseler SM. Diagnosing central nervous system vasculitis in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:731–8. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283402d4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gowdie P, Twilt M, Benseler SM. Primary and secondary central nervous system vasculitis. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:1448–59. doi: 10.1177/0883073812459352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajj-Ali RA, Singhal AB, Benseler S, Molloy E, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:561–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alba MA, Espígol-Frigolé G, Prieto-González S, Tavera-Bahillo I, García-Martínez A, Butjosa M, et al. Central nervous system vasculitis: Still more questions than answers. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:437–48. doi: 10.2174/157015911796557920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:704–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLaren K, Gillespie J, Shrestha S, Neary D, Ballardie FW. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: Emerging variants. QJM. 2005;98:643–54. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iannetti L, Zito R, Bruschi S, Papetti L, Ulgiati F, Nicita F, et al. Recent understanding on diagnosis and management of central nervous system vasculitis in children. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:698327. doi: 10.1155/2012/698327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elbers J, Benseler SM. Central nervous system vasculitis in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:47–54. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f3177a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berlit P. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral vasculitis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:29–42. doi: 10.1177/1756285609347123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]