Abstract

Exome sequencing identified homozygous loss-of-function variants in DIAPH1 (c.2769delT; p.F923fs and c.3145C>T; p.R1049X) in four affected individuals from two unrelated consanguineous families. The affected individuals in our report were diagnosed with postnatal microcephaly, early-onset epilepsy, severe vision impairment, and pulmonary symptoms including bronchiectasis and recurrent respiratory infections. A heterozygous DIAPH1 mutation was originally reported in one family with autosomal dominant deafness. Recently, however, a homozygous nonsense DIAPH1 mutation (c.2332C4T; p.Q778X) was reported in five siblings in a single family affected by microcephaly, blindness, early onset seizures, developmental delay, and bronchiectasis. The role of DIAPH1 was supported using parametric linkage analysis, RNA and protein studies in their patients’ cell lines and further studies in human neural progenitors cells and a diap1 knockout mouse. In this report, the proband was initially brought to medical attention for profound metopic synostosis. Additional concerns arose when his head circumference did not increase after surgical release at 5 months of age and he was diagnosed with microcephaly and epilepsy at 6 months of age. Clinical exome analysis identifieda homozygous DIAPH1 mutation. Another homozygous DIAPH1 mutation was identified in the research exome analysis of a second family with three siblings presenting with a similar phenotype. Importantly, no hearing impairment is reported in the homozygous affected individuals or in the heterozygous carrier parents in any of the families demonstrating the autosomal recessive microcephaly phenotype. These additional families provide further evidence of the likely causal relationship between DIAPH1 mutations and a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Keywords: DIAPH1, microcephaly, blindness, seizures, intellectual disability, deafness

INTRODUCTION

Microcephaly is defined as an occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) of more than two standard deviations (SD) below the mean for a given age, sex, and gestation. Microcephaly may be primary (i.e., present at birth) or postnatal. The prototype of primary microcephaly is microcephaly vera, also referred to as autosomal recessive microcephaly, in which there is reduced cerebral volume but no other brain malformations. In this condition, microcephaly is typically evident by 34 weeks of gestation [Woods and Parker, 2013]. Most genes associated with microcephaly vera thus far encode proteins that regulate cellular processes including centrosome and mitotic spindle formation, cell-cycle progression and DNA repair. It is presumed that mutations in these genes result in the reduction of in utero neurogenesis and manifest as microcephaly. In contrast, in postnatal microcephaly, head size is normal at birth, but falls off the growth curve and often reflects a neurodegenerative process. Genetic etiologies appear to account for a significant proportion of both primary and postnatal microcephaly. The underlying genetic defects of microcephaly are highly heterogeneous, but with the advent of next generation sequencing technologies, exact molecular diagnoses are becoming more achievable [Mahmood et al., 2011; Woods and Parker, 2013].

Recently, a nonsense homozygous mutation in DIAPH1 (OMIM 602121) was reported in a single large consanguineous family from Saudi Arabia, in which five siblings were affected by microcephaly, severe visual impairment, early onset seizures, global developmental delay, and short stature [Ercan-Sencirek et al., 2015]. In the family reported, parametric linkage analysis identified only a single linkage peak on chromosome 5q31.3 with a LOD score of 3.7, at the DIAPH1 Locus. Studies of the RNA levels from patients’ cell lines confirmed non-sense mediated decay and immunoblot confirmed complete absence of DIAPH1 protein. Further studies showed the expression of diap1 in fetal and adult mouse brain.

Here we report two unrelated families with a total of four individuals presenting with postnatal microcephaly, vision impairment, early onset seizures, and respiratory complications. Exome sequencing identified homozygous, loss-of-function mutations in DIAPH1 (c.2769delT; p. F923fs and c.3145C>T; p.R1049X, RefSeq NM_005219.4) in the affected individuals. These additional families support the association between DIAPH1 mutations and a neurodevelopmental disorder and further delineate the associated phenotype.

CLINICAL REPORT

Family MC36500: The male proband (MC36501) was the 2.85 kg, 52 cm long product of an uncomplicated 39 weeks gestation to a 38-year-old G5P4 mother (MC36502) and 47-year-old father (MC36503) from the United Arab Emirates. There were no known teratogenic exposures and a prenatal ultrasound was reported as normal. The family history was notable only for the parents being half first cousins (Fig. 1A). He was born by a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. At birth, he was noted to have trigonocephaly. At 11 weeks of age, while being evaluated for craniosynostosis, his OFC was 37 cm (−2.2 SD), and his neurological exam was normal. Endoscopic release of the metopic suture was performed at 5 months of age. His head size continued to fall off the standard growth curve. Motor delays and chronic respiratory concerns were noted and prompted a genetics evaluation. At 6 months of age, he developed seizures, consisting of opening his eyes with deviation to the left and left arm movement. An electroencephalography (EEG) showed left occipital area spikes, evolving into rhythmic activity including the left posterior quadrants.

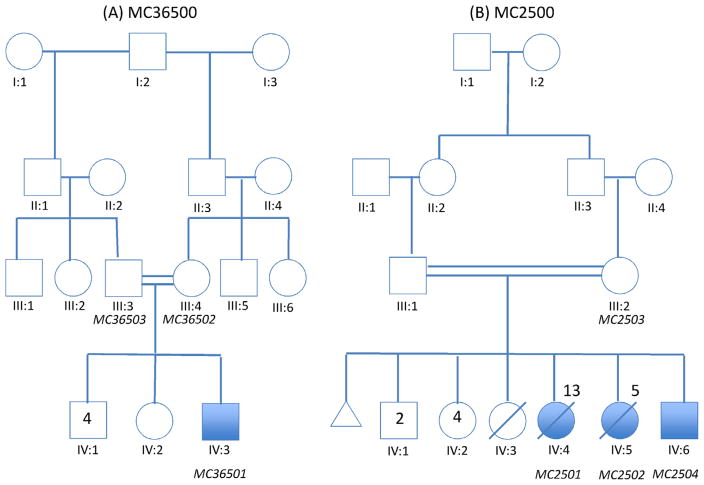

FIG. 1.

Pedigrees of two consanguineous families with homozygous loss-of-function mutations in DIAPH1. Individuals with “MC” nomenclature represent DNA samples analyzed. (A) Family MC36500 is from the United Arab Emirates. (B) Family MC2500 is from Oman. MC2501 died of pneumonia, and MC-2502 died of seizures. IV:3 died of unknown causes but was not known to be similarly affected.

At 15 months old, he was 75.9 cm long (15th centile), weighed 11.35 kg (60th centile) and had an OFC of 39.6 cm (−6 SD). He had no facial dysmorphic features. There was one 0.5 × 0.5 cm café-au-lait macule on the right side of the neck. There was generalized hypotonia with normal motor strength and deep tendon reflexes. He was visually inattentive and had limited social interaction. An ophthalmological examination showed pale optic discs and he could recognize light only. His audiology examination was normal.

He had global developmental delay with crawling at 14 months and walking at 2 years of age. He had 2–3 words by 2 years and 7 month sand was able to understand simple commands. Recurrent sinopulmonary infections required multiple courses of antibiotics and one admission to the intensive care unit. Sweat testing and immunological function screenings were normal. His echocardiography showed a patent foramen ovale and an abdominal ultrasound was normal. His seizures were difficult to control requiring multiple anti-epileptic medications.

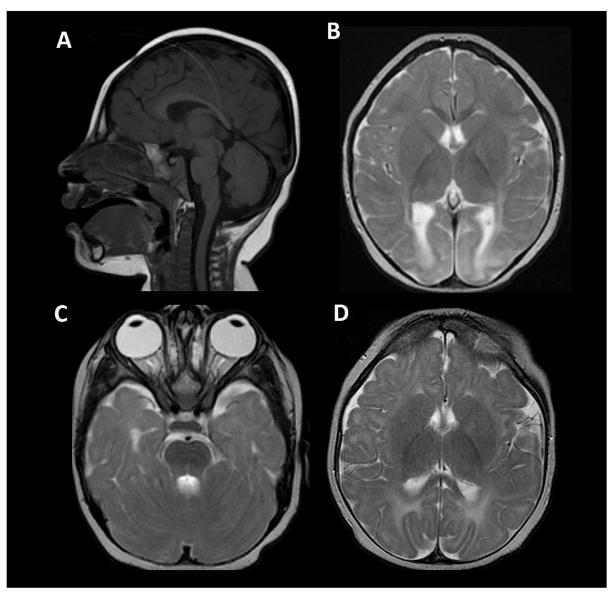

Microarray analysis (Agilent 180 K with enhanced SNP for homozygosity areas) revealed a normal male karyotype (46, XY) and showed multiple regions of homozygosity. A microcephaly panel including the genes ARFGEF2, ASPM (Sanger sequencing and deletions/duplications), CDK5RAP2, CENPJ, CEP152, MED17, NDE1, RAB3GAP2, PNKP, RAB18, RAB3GAP1, RAB3-GAP2, SLC25A19, STIL, and WDR62 showed no significant findings. Basic metabolic investigations were unremarkable. Brain MRI at 1 year and 8 months showed diffusely severely diminished white matter and atrophy of the cerebral cortex in the occipital and posterior temporal lobes bilaterally. In addition, he had a thin posterior body and splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

(A–C) brain MRI at 18 months. Sagittal T1 imaging demonstrates craniofacial disproportion and moderately depressed thickness of the posterior corpus callosum. There is preserved volume of the posterior fossa structures. (B) Axial T2 weighted imaging at the level of the internal capsules demonstrates pronounced T2 signal increase within the occipital poles suggestive of dysmyelination. The signal characteristics and myelination of the brain remain otherwise normal for age. (C) Axial T2 imaging at a lower level demonstrates grossly intact size of the optic nerves. The temporal lobes are small but in proportion to the remainder of the brain. (D) Axial T2 imaging of the brain at the level of the internal capsules, 9 months of age. The occipital pole signal abnormality is less conspicuous due to the early stage of myelination at this age. This exam also shows grossly intact cortical thickness and morphology.

Family MC2500: This family includes a sibship of three brothers and seven sisters in which two females and one male are affected with microcephaly. Their parents are first cousins of Omani ancestry (Fig. 1B). One female child (IV:3) died of uncertain cause in infancy. At birth the proband (IV:4) was 49 cm long (42nd centile), weighed 3.2 kg (33rd centile) and had an OFC of 33 cm (11th centile). There was no developmental concern until 4 months of age when seizures, microcephaly and developmental delay became apparent. Subsequently seizures became refractory to medical treatment. She had optic atrophy and was diagnosed with cortical blindness by visual evoked potential (VEP). By age 9 years she had short stature with a height of 99 cm (−5.7SD), microcephaly with an OFC of 43 cm (−7.5SD) and global developmental delay. She had slender bones on X-ray, finger clubbing and severe bronchiectasis. She died of pneumonia at age 13 years.

Her younger sister (IV:5) presented similarly with a birth weight of 3.1 kg (23rd centile, [−0.74 SD]), length of 51 cm (62nd centile, [−0.3 SD]), and an OFC of 32 cm (4th centile, [−1.7 SD]). Epilepsy developed at 3 months of age and subsequently global developmental delay was noted. She had optic atrophy and was diagnosed with cortical blindness by VEP. She died at age 5 years from complications of epilepsy.

The affected male (IV:6) presented at 1 week of age with cyanotic episodes and subsequent EEG showed hypsarrhythmia. The cyanotic episodes stopped at around age 3 months and he started having generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Assessment at age 1 year and 9 months revealed global developmental delays. He was able to roll, sit and pull to stand, but was not able to crawl or walk. He could babble but had no words. Physical examination showed microcephaly with an OFC of 42.5 cm (−4.2 SD), exotropia, generalized hypotonia, and normal DTRs. There was one 1.5 cm × 3 cm café-au-lait macule on the lower right back. He also was treated for significant gastro-esophageal reflux. The ophthalmological exam showed pale optic discs and he was confirmed to have cortical blindness by VEP.

Brain imaging of the affected individuals is not available for review in this family, but the male was reported to have abnormal lateral ventricles with a question of a corpus callosum abnormality. More phenotypic details are provided in Table I.

TABLE I.

Summary of the Clinical Phenotype of Patients

| Report | Ercan-Sencirek et al. (2015) | Present study | Present study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family (ancestry) | SAR1008 (Saudi Arabian) | MC2500 (Omani) | MC36500 (Emirati) | ||||||

| DIAPH1 mutation | c.2332C >T(p.Q778X) | c.2769delT(p.F923fs) | c.3145C >T(p.R1049X) | ||||||

| Affected individual | IV:4 | IV:5 | IV:6 | IV:7 | IV:8 | IV:4 | IV:5 | IV:6 | IV:1 |

| Gender | F | F | F | M | M | F | F | M | M |

| Birth weight | 2.4 kg (3%ile) | 2.4 kg (3%ile) | “low“ | 2.56 kg (5%ile) | 2.7 kg (8%ile) | 3.2 kg (33%ile) | 3.1 kg (27%ile) | NA | NA |

| Birth length | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 49 cm (42%ile) | 51 cm (71%ile) | NA | NA |

| Birth HC | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 33 cm (11%ile) | 32 cm (3%ile) | NA | NA |

| Presenting concerns (age) | Seizures (3 m) | Seizures (3 m) | Seizures (3 m) | Seizures (3 m) | Abnormal eye movements, microcephaly (3 m) | Seizures (4 m) | Seizures (3 m) | Cyanotic episodes (8 d) | Metopic craniosynostosis (birth); lack of head growth and microcephaly after surgical release (6 m); seizures (6 m) |

| Age at most recent assessment (age) | 15 y 11 m | 14 y | 6 y 11 m | 25 m | 15 w | 9 y | 9 m | 21 m | 2 y 9 m |

| Weight | 20 kg (−5.0 SD) | 16.2 kg (−4.9 SD) | 12 kg (−4.0 SD) | 10.2 kg (−2.1 SD) | 5 kg (−1.8 SD) | 10.5 kg (−4.6 SD) | 4.2 kg (−5.0 SD) | NA | 13.3 kg (−0.5 SD) |

| Height | 127 cm (−5.5 SD) | 116 cm (−6.8 SD) | 100 cm (4.1 SD) | 85 cm (−0.9 SD) | NA | 99 cm (−5.7 SD) | 71 cm (0.4 SD) | NA | 88.3 cm (−1.5 SD) |

| OFC | 43.5 cm (−10. 2 SD) | 42.5 cm (−10.2 SD) | 43 cm (−6.9 SD) | 41.5 cm (−5.0 SD) | 32 cm (−6.8 SD) | 43 cm (−7.5 SD) | 42 cm (−1.6 SD) | 42.5 cm (−4.2 SD) | 40.5 cm (−5.5 SD) |

| Functioning level at assessment | Could sit, walk, social, understand simple commands, had two word sentences by age 3 y. | Could sit, walk, language limited to 2 word sentences, difficult to understand, could wave goodbye, dress self, had bowel and bladder control. | Could sit, walk, understand simple commands feed self, dress self, use toilet, imitate play. | Could sit, walk, had 2 single words, followed simple commands. | Did not appear to see objects in environment or light, delayed milestones. | Could walk, cognition like 1 y old, some head banging. | Could sit at 8 m, low tone, global motor delays. | Low tone. | Could walk, feed self with hands but no utensils, follow simple commands, had 5 words. |

| Seizures | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Vision problems/cortical visual impairment | + | + | + | + | + | + & optic atrophy | + & optic atrophy | + & optic atrophy | + |

| Pulmonary/respiratory | Severe bronchiectasis, underwent L lobectomy. | NR | NR | NR | NR | Severe bronchiectasis | NR | NR | Early concerns for wheezing, desaturations, required oxygen for several months. |

| Brain imaging | Normal CT by report | Abnormal | Normal MRI by report | Abnormal | Not done | Not done | Not done | Abnormal | Abnormal |

| Other history and findings | Mildly cyanotic at birth requiring oxygen but not intubation. Delayed puberty | Delayed puberty | — | — | — | Slender bones on X-ray, very thin build, clubbing of fingers. | — | Café au lait 1.5 cm × 3 cm on lower R back. | Metopic synostosis. Café au lait 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm on neck. |

| Cause of death (age) | Alive* | Chest infection (18 y) | Alive* | Alive* | Alive* | Pneumonia (13 y) | Seizures (5 y) | Alive* | Alive* |

HC, head circumference; M, male; F, female; y, year; m, month; d, day; SD, standard deviation; NA, Not available; NR, Not reported.

Alive at latest assessment.

METHODS

Human Studies

All participating families provided written informed consent for participation in a study protocol approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital institutional review board.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. Genomic DNA of the proband and both parents in family MC36500 was sent for clinical exome analysis (GeneDx, Gaithersburg, MD), which was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2,500 sequencing system with 100 bp paired-end reads. Individual IV:4 in family MC2500 underwent whole exome sequencing on a research basis. The genomic DNA was subjected to array capture by SureSelect Human Exon kit (Agilent Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Adapters were ligated, and 76 basepair paired-end sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2,000 at the Broad Institute producing ~6 Gb of sequence, covering 87% of the target sequence at least 20 times. Sequencing reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19) using BWA (0.5.7), consensus and variant bases were called using GATK (3.1) and variants were annotated with ANNOVAR (version 2014Nov12). Annotated variants were entered into a MySQL database and filtered with custom queries. An autosomal recessive mode of inheritance with homozygous high impact mutations were presumed during the search for candidate variants. Candidate gene variants and segregation were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

RESULTS

Exome Sequencing Identifies Mutations in DIAPH1

Clinical exome analysis for the male proband (MC36501) initially was unrevealing for a definitive cause for his craniosynostosis or neurological symptoms. The initial exome report included reference to a homozygous variant chr5:140908023 (hg19) G>A (NM_005219.4: c.3145C>T; p.R1049X) classified as a variant of uncertain significance in a gene (DIAPH1) not previously associated with human disease. On subsequent exome re-analysis and update, this variant was re-classified to be a causative pathogenic variant. Based on the identification of DIAPH1 as a candidate gene for microcephaly in this individual, we searched our in-house exome data of individuals with microcephaly for rare DIAPH1 variants. We identified a homozygous mutation chr5:140908747 (hg19) delA (NM_005219.4:c.2769delT; p.F923fs) in the proband (IV:4) of family MC2500. We performed Sanger sequencing of this mutation in MC2501 (IV:4), MC2502 (IV:5) and MC2503 (III:3) and confirmed the segregation with the phenotype. Both variants identified in this study are absent from the public database including Exome Variant severe (EVS) and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) and also absent in our in-house control exome (n = 1200) data which is well represented for the Middle Eastern population.

DISCUSSION

DIAPH1 encodes for the mammalian diaphanous-related formin protein, mDia1, which plays a role in the regulation of cell morphology and cytoskeletal organization [Shinohara et al., 2012]. In embryonic mouse brain it is expressed widely in the brain, including the ventricular and subventricular zone progenitor cells of the forebrain and the brainstem [Ercan-Sencirek et al., 2015]. During mouse postnatal development, it is expressed in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus, thalamus, and external granular layer of the cerebellum. It was shown to co-localize with centrosomes but was mostly concentrated on mitotic spindles in mitosis during M phase. Mice lacking mDia1 revealed only enlarged lateral ventricles but not microcephaly or callosal hypoplasia [Ercan-Sencirek et al., 2015]. Nevertheless, DIAPH1 has been shown to be involved in cell migration where cytoskeletal dynamics is essential. It is required to slow down actin polymerization and depolymerization, stabilize microtubules and promote cell migration [Zaoui et al., 2010; Bai et al., 2011].

Including this report, DIAPH1 biallelic mutations have now been identified in three consanguineous families. The prenatal and perinatal history (Table I) are characterized by normal pregnancy and prenatal ultrasounds (at 18–20 weeks of gestation), normal delivery, and normal growth parameters at birth. Concerns were raised after the onset of seizures and development of microcephaly. The earliest onset of seizures in one individual (MC2500; IV:6) was around the time of birth manifesting as cyanotic episodes. In the other cases, the onset of seizures was at around 3 months and were mainly generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The latest onset was at 6 months with complex partial seizures. The response to antiepileptic medications was inconsistent. Microcephaly was evident by the time these individuals presented with seizures (at 3–6 months) and progressed to −10.2 SD below the mean in the most severely affected individual. Cortical visual impairment, confirmed by VEP, was a common feature among all affected individuals. The brain MRI in one of the individuals (MC36501) showed diffusely severely diminished white matter and atrophy of the cerebral cortex at the occipital and posterior temporal lobes bilaterally. In addition, the posterior body and splenium of the corpus callosum was thin. These findings are similar to those of two previously reported individuals, who also showed bilateral cortical atrophy of the occipital and temporal lobes and reduced white matter. These findings are similar to that seen from neonatal hypoglycemia or vascular injury but none of the reported individuals had a history of such events. Metopic craniosynostosis requiring surgical intervention was noted in one (MC36501, IV:3) of the nine reported individuals.

Global developmental delay was prominent in all. There was no regression of milestones and metabolic screening was normal. In general all individuals were able to sit and walk but at later ages. Receptive language was better than expressive language. Some of the individuals were able to communicate with two words sentences and were able to follow simple commands by age 3–4 years. None were reported as having stereotypical behaviors or mannerisms. Mild to moderate growth retardation was noted and worsened over time.

Recurrent sinopulmonary infections were a prominent feature in this syndrome, despite normal immunological investigations. One of the individuals (IV:4) previously reported by Ercan-Sencirek et al. required pulmonary lobectomy for bronchiectasis by mid-teenage years. In our cohort of patients, individual MC2501 (IV:4) had severe bronchiectasis and died of pneumonia, while individual MC36501 (IV:3) had early wheezing, required oxygen for 7 months, and underwent repeated treatments for chronic cough and secretions.

A heterozygous variant in DIAPH1 was reported in a Costa Rican kindred with autosomal dominant sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) [Lynch et al., 1997]. Deafness was not identified in any of the affected individuals or their carrier parents in the families reported here or in the previously reported family with a homozygous DIAPH1 mutation [Ercan-Sencirek et al., 2015]. This suggests that different DIAPH1 mutations may cause sensorineural hearing loss and syndromic microcephaly by different pathogenic mechanisms. The mutations identified in patients with the syndromic microcephaly are likely to lead to a complete loss-of-function of the protein. On the other hand, the sensorineural hearing loss in the Costa Rican kindred is associated with a guanine-to-thymine substitution in the splice donor of the penultimate exon of DIAPH1. This splicing mutation (c.3661+1G>T; IVS27 ds G-T +1, RefSeq: NM-005219) was shown to lead to activation of a cryptic splice donor site in intron 27 and inclusion of four aberrant base pairs in the mRNA [Lynch et al., 1997]. This mRNA change is predicted to cause a frame-shift, encoding 21 aberrant amino acids, followed by a protein termination that truncates 32 amino acids at the C-terminal (p. Ala1221Valfs*22, NP-005210). Further functional studies are needed to understand the pathogenesis of these two distinct conditions associated with DIAPH1 mutations.

In summary, we report two additional families with biallelic DIAPH1 mutations in the affected individuals. This supports the implication of biallelic loss-of-function mutations in DIAPH1 with a unique syndrome of early onset seizures, progressive microcephaly, intellectual disability and severe visual impairment.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NINDS; Grant number: R01 NS 35129.

C.A.W. is supported by the NINDS (R01 NS 35129). C.A.W. is a distinguished investigator of the Paul G. Allen foundation and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We like to acknowledge the multiple clinicians involved in the care of this patient.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- Bai SW, Herrera-Abreu MT, Rohn JL, Racine V, Tajadura V, Suryavanshi N, Bechtel S, Wiemann S, Baum B, Ridley AJ. Identification and characterization of a set of conserved and new regulators of cytoskeletal organization, cell morphology and migration. BMC Biol. 2011;9:54. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan-Sencirek AG, Jambi S, Franjic D, Nishimura S, Li M, El-Fishawy P, Morgan TM, Sanders SJ, Bilguvar K, Suri M, Johnson MH, Gupta AR, Yuksel Z, Mane S, Grigorenko E, Picciotto M, Alberts AS, Gunel M, Šestan N, State MW. Homozygous loss of DIAPH1 is a novel cause of microcephaly in humans. Eur Journal Hum Genet. 2015;23:165–172. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ED, Lee MK, Morrow JE, Welcsh PL, León PE, King MC. Nonsyndromic deafness DFNA1 associated with mutation of a human homolog of the Drosophila gene diaphanous. Science (New York, NY) 1997;278:1315–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood S, Ahmad W, Hassan MJ. Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH): Clinical manifestations, genetic heterogeneity and mutation continuum. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara R, Thumkeo D, Kamijo H, Kaneko N, Sawamoto K, Watanabe K, Takebayashi H, Kiyonari H, Ishizaki T, Furuyashiki T, Narumiya S. A role for mDia, a rho-regulated actin nucleator, in tangential migration of interneuron precursors. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:373–380. S371–372. doi: 10.1038/nn.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CG, Parker A. Investigating microcephaly. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:707–713. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaoui K, Benseddik K, Daou P, Salaün D, Badache A. ErbB2 receptor controls microtubule capture by recruiting ACF7 to the plasma membrane of migrating cells. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18517–18522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000975107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]