Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia earlier had limited pathogenic potential, but now with growing degree of immunosuppression in general population, it is being recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen.

METHODOLOGY:

A retrospective 7 years study was carried out to determine the clinical characteristics of all patients with Stenotrophomonas infections, antibiotic resistance pattern, and risk factors associated with hospital mortality. All patients with Stenotrophomonas culture positivity were identified and their medical records were reviewed. Risk factor associated with hospital mortality was analyzed.

RESULTS:

A total of 123 samples obtained from 88 patients were culture positive. Most patients presented with bacteremia (45, 51%) followed by pneumonia (37, 42%) and skin and soft tissue infections (6, 7%). About 23 of 88 Stenotrophomonas infected patients had co-infection. Percentage resistance to cotrimoxazole; 8 (5.4%) was lower than that for levofloxacin; 18 (12%). Twenty-eight patients died during hospital stay. Intensive Care Unit admission (P = 0.0002), mechanical ventilation (P = 0.0004), central venous catheterization (P = 0.0227), urethral catheterization (P = 0.0484), and previous antibiotic intake (P = 0.0026) were independent risk factors associated with mortality.

CONCLUSION:

Our findings suggest that Stenotrophomonas can cause various infections irrespective of patient's immune status and irrespective of potential source. Thus, Stenotrophomonas should be thought of as potential pathogen and its isolation should be looked with clinical suspicion.

Keywords: Epidemiology, risk factors, Stenotrophomonas

Introduction

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (earlier classified as Pseudomonas or Xanthomonas maltophilia) is an aerobic, nonglucose fermenting, Gram-negative rod shaped, nonspore forming, nonacid fast facultative aerobes, which is widely distributed in the natural and hospital environment. This pathogen was earlier considered to have limited pathogenic potential, but now with the growing degree of immunosuppression in general population,[1] it is being recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen. It is now seen to be associated with severe infections in hospitalized patients including bacteremia, biliary and urinary tract infections, respiratory tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, bone and joint infections, endocarditis, meningitis, and ocular infections.[2]

Patients who are at an increased risk of acquiring infections with Stenotrohphomonas spp. are those with previous history of antibiotic therapy, patients with severe underlying comorbidities such as chronic liver and kidney disease or connective tissue disorders, immunocompromised patients such as HIV or underlying malignancies, mechanical ventilation, and patients admitted to the Intensive Care Units (ICUs).[3,4]

Infections caused by S. maltophilia are difficult to treat because of their intrinsic resistance to a variety of antibiotics, ability of biofilm formation, and production of various extracellular enzymes. Cotrimoxazole still remains the most effective treatment modality for Stenotrophomonas infections. However, drug resistance has been increasingly noted against this drug also.[2]

Stenotrophomonas infections have been rarely described from India with only few case reports of ocular infections, pyomyositis, respiratory tract infections, meningitis, osteomyelitis, etc.[5,6,7,8] This is the first case series of all kinds of infections by Stenotrophomonas from trauma patients. In a retrospective study of 7 years duration, the clinical characteristics of all patients with Stenotrophomonas infections were studied, the antibiotic resistance pattern of the isolates and the risk factors associated with in hospital mortality was also studied.

Methodology

Hospital setting and patient selection

This study was performed at Jai Prakash Narayan Apex Trauma Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, a 165 bedded hospital. All patients culture positive for S. maltophilia over a period of 7 years, from 2007 to 2014, were identified from the hospital's computerized database. This was followed by a detailed review of their medical records. No standardized protocol was defined for obtaining the information during the study period.

Information about the patients’ age, sex, underlying diseases, history of antibiotic intake prior to the isolation of Stenotrophomonas, history of catheterization (urinary or intravenous) was recorded. Standard Center for Disease Control and Prevention protocol was used to define hospital acquired infection,[9] skin and soft tissue infection,[10] blood stream infection,[10] and lower respiratory tract infection.[10] Polymicrobial infections were diagnosed in patient from whom Stenotrophomonas isolates were isolated in addition to other pathogens from the same specimen. In-hospital mortality was taken as death due to any cause during hospitalization.

Laboratory methods

All the isolates obtained were identified using conventional methods (microscopy, culture characteristics, and standard biochemical tests)[11] and Vitek 2 identification system (Biomerieux, France) using GN card. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of these isolates to a battery of antimicrobial agents was determined using the disk diffusion method as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute[12] and by the Vitek 2 AST card.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to explore the various risk factors associated with infection-attributed mortality. Univariate analyses were performed separately for each variable and the variables with P < 0.05 and high relative risks in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in the logistic regression model for multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

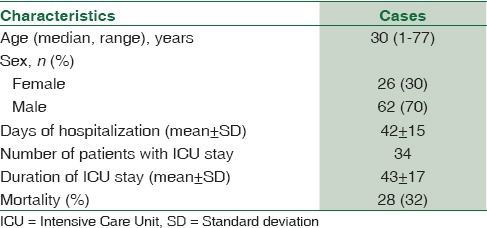

During the 7 years study period, a total of 123 samples obtained from 88 patients were culture positive for Stenotrophomonas. Demographic and basic characteristics of the 88 patients having Stenotrophomonas infection is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and basic characteristics of 88 patients infected with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

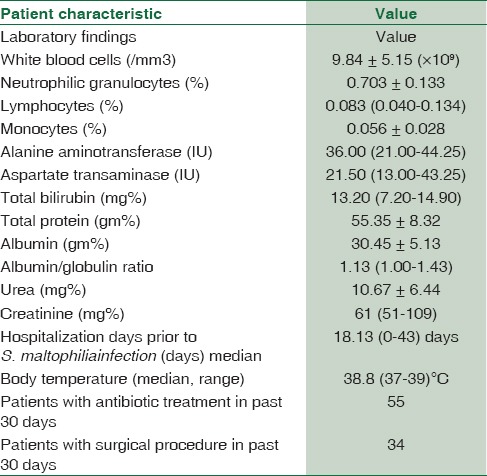

Characteristics of the patients at the onset of Stenotrophomonas infection are given in Table 2. Most of the patients presented with bacteremia (45, 51%) followed by pneumonia (37, 42%) and skin and soft tissue infections (6, 7%). A total of 49 (55%) patients had mechanical ventilation before the onset of Stenotrophomonas infection and the mean duration of mechanical ventilation was 16.4 ± 15 days. Forty-four (50%) patients had central venous catheter with the mean duration of catheterization before the onset of Stenotrophomonas infection being 17.6 ± 10.9 days. Seventy-four (85%) patients had urinary catheter with the mean duration before the onset of infection being 18.0 ± 14.8 days.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients at the onset of Stenotrophomonas infection

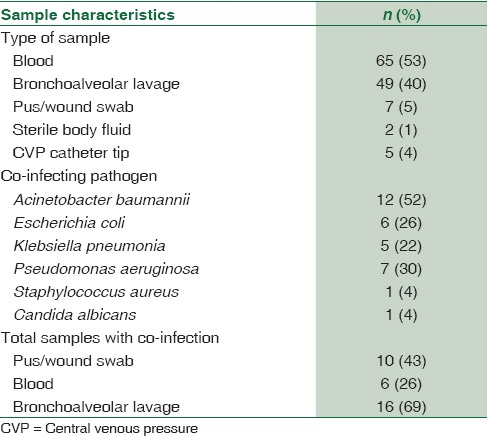

Twenty three of the 88 Stenotrophomonas infected patients had co-infection. Characteristics of the samples with Stenotrophomonas isolate is described in Table 3. The percentage resistance to cotrimoxazole; 8 (5.4%) was lower than that observed for levofloxacin; 18 (12%).

Table 3.

Characteristics of samples with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates

Risk factors for death

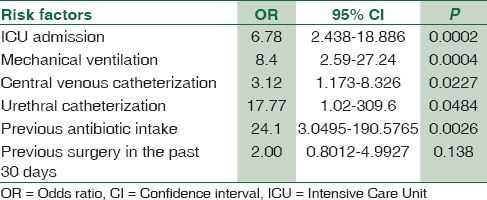

Twenty-eight patients died during the hospital stay. As per the multivariate logistic regression model, ICU admission (odds ratio [OR]: 6.78, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.438–18.886, P - 0.0002), mechanical ventilation (OR: 8.4, 95% CI: 2.59–27.24, P - 0.0004), central venous catheterization (OR: 3.12, 95% CI: 1.173–8.326, P - 0.0227), urethral catheterization (OR: 17.77, 95% CI: 1.02–309.6, P - 0.0484), and previous antibiotic intake (OR: 24.1, 95% CI: 3.0495–190.5765, P - 0.0026) were independent risk factors associated with mortality. Previous surgery in the past 30 days (OR: 2.00, 95% CI: 0.8012–4.9927, P - 0.138) was not associated with the patient's in-hospital mortality. The OR, CI, and P value of all the risk factors are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Odds ratio, confidence interval, and P value of the risk factors studied

Discussion

S. maltophilia has gained importance since the past decade, especially in the ICU setting with the growing level of immunosupression and has become the third most common nonfermentative Gram-negative bacilli responsible for nosocomial infections, after P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp.[13] Most authors have studied S. maltophilia infection as an opportunistic nosocomial pathogen in selected groups of patients (e.g., hematology, ICU), and most authors have also combined colonization with infection.[14] The present study is the largest case series of all nosocomial Stenotrophomonas infections from India from trauma victims having no predisposing factor for immunosuppression.

The main type of infection caused by S. maltophilia was bacteremia followed by respiratory tract infection. This is in contrast to the other studies where respiratory tract infections are most common.[2,15] The main characteristics of the patients were prolonged use of mechanical ventilation (77.5%, average 16.4 days), urethral catheter (85%, average 14.0 days), and central venous catheter (57.5%, average 15.6 days). These findings were similar to the findings in other studies.[14,16] Garcia Paez and Costa found the duration of therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics, use of devices such as central venous access/mechanical ventilation and severe neutropenia to be independent risk factors for Stenotrophomonas infection.[14]

ICU stay, mechanical ventilation, previous antibiotic intake, and central venous and urinary catheterization were found to be independent risk factors for mortality by univariate analysis. Studies conducted by other authors have also found similar results.[16] S. maltophilia produces a diffusible signaling factor which enables biofilm formation and resistance to heavy metals, i.e., tolerance to silver lined catheters.[17]

Increasing resistance in Stenotrophomonas spp. has been noted to ticarcillin/clavulanate and cotrimoxazole worldwide.[2] However, in our study, only 5.4% and 12% strains were resistant to cotrimoxazole and levofloxacin, respectively. The increasing usage of higher generation drugs such as ofloxacin, augmentin, and azithromycin the usage of drugs such as cotrimoxazole and levofloxacin has decreased. This could explain the lower resistance reported to these drugs in our hospital as most patients getting treatment in our hospital represent general population. Being a retrospective study, level of resistance to ticarcillin-clavulanate could not be assessed.

Many studies have reported hypotension and hypoalbuminemia to be important risk factors for mortality.[3] However, being a retrospective, these parameters could not be obtained and assessed. Detailed information on the treatment administered to the patient after the isolation of Stenotrophomonas could not be elicited and thus the in vivo susceptibility of the pathogen could not be assessed.

Other potentially active agents effective against S. maltophilia, such as levofloxacin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, minocycline, and chloramphenicol, were not tested in our hospital and estimates of their clinical effects are unavailable.

Conclusion

The study conducted by use thus proves that Stenotrophomonas can cause various infections irrespective of patient's immune status. Its isolation in samples should be looked at with clinical suspicion and should not be disregarded as a mere commensal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Low CY, Rotstein C. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Rep. 2011;3:14. doi: 10.3410/M3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu H, Wang JT, Shiau YR, Wang HY, Lauderdale TL, Chang SC. TSAR Hospitals. A multicenter surveillance of antimicrobial resistance on Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xun M, Zhang Y, Li BL, Wu M, Zong Y, Yin YM. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of infections caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in a hospital in Northwest China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:1000–5. doi: 10.3855/jidc.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naeem T, Absar M, Somily AM. Antibiotic resistance among clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia at a teaching hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2012;24:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhablani J, Sudhalkar A, Jindal A, Das T, Motukupally SR, Sharma S, et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endogenous endophthalmitis: Clinical presentation, antibiotic susceptibility, and outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1523–6. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S67396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla K, Vishwanath S, Munim FC. Nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. Causing respiratory tract infections in a tertiary care center. J Glob Infect Dis. 2013;5:144–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.121996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooke JS. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: An emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:2–41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas J, Prabhu VN, Varaprasad IR, Agrawal S, Narsimulu G. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: A very rare cause of tropical pyomyositis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:89–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:128–40. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipuma JJ, Curie BJ, Peacock SJ, Vandamme PAR. Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Ralstonia, Cupriavidus, Pandoraea, Brevundimonas, Comamonas, Delftia, and Acidovorax. In: Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Jorgensen JH, Yolken RH, editors. Mannual of Clinical Microbiology. 8th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2010. pp. 692–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty Third Informational Supplement CLSI Document M100-S23. Vol. 33. Wayne, PA: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winn WC, Allen SD, Allen S, Janda WM, Koneman EW, Schreckenberger PC, et al. Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 6th ed. United States of America: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naidu P, Smith S. A review of 11 years of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia blood isolates at a tertiary care institute in Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2012;23:165–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/762571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai CH, Chi CY, Chen HP, Chen TL, Lai CJ, Fung CP, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:350–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CH, Lin JC, Lin HA, Chang FY, Wang NC, Chiu SK, et al. Comparisons between patients with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-susceptible and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia monomicrobial bacteremia: A 10-year retrospective study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouhy Y, Scanlon K, Schouest K, Spillane C, Crossman L, Avison MB, et al. Diffusible signal factor-dependent cell-cell signaling and virulence in the nosocomial pathogen Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4964–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.00310-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]