Abstract

This study replicated the Child Behavior Checklist factor structure of traumatic sequelae in maltreated children that was established by A. C. Hulette and colleagues (in press; see also A. Cholankeril et al., 2007). The factors represent dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology. The present study also examined the extent to which these 2 factor scores varied depending on specific maltreatment experiences. Results indicated that children who experienced both physical and sexual abuse in addition to neglect had significantly higher levels of dissociation than children who experienced (a) sexual abuse alone or with neglect, (b) physical abuse alone or with neglect, or (c) only neglect. The current study provides evidence that children who experience multiple forms of maltreatment are more likely to be dissociative, perhaps due to a greater need for a coping mechanism to manage the distress of that maltreatment.

Keywords: Dissociation, PTSD, maltreatment, child abuse, preschoolers

Although the trauma of childhood maltreatment has been associated with the development of dissociation (Briere, 1992; Freyd, 1996; Hornstein, 1993; Liotti, 1999; Putnam, 1997; Terr, 1991), there have been few studies of dissociation in early childhood. From a developmental psychopathology perspective (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), it is particularly important to examine the impact of early child maltreatment to prevent cascading developmental problems and posttraumatic psychiatric sequelae.

Briere (1992) referred to dissociation as “a defensive disruption in the normally occurring connections among feelings, thoughts, behavior, and memories … invoked in order to reduce psychological distress” (p. 34). Although dissociation enables the child to cope with the distress of maltreatment, it is pathological when it has a negative impact on overall functioning and well-being. Abuse survivors may exhibit abrupt changes in mannerisms, access to knowledge, and age-appropriate behavior (Putnam, 1997). High levels of dissociation in childhood appear to result in problems negotiating developmental challenges and are frequently comorbid with other psychopathology (Putnam, 1997).

Although the main focus of this study was dissociation, we also examined posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomatology following child maltreatment. It has been estimated that one-third of individuals who experience maltreatment meet criteria for lifetime PTSD (Widom, 1999). PTSD contains three main symptom clusters: intrusion, hyperarousal, and avoidance (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Intrusion symptoms include recurrent nightmares/flashbacks and distress toward trauma-related cues. Hyperarousal symptoms include sleep difficulties, increased vigilance or anxiety, and irritability. Avoidance symptoms include an aversion to triggers that may precipitate memories of the traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Avoidance may appear to be similar to dissociation, but it does not encompass the full set of disturbances that occur to the integrated systems of consciousness, memory, identity, and perception that are associated with dissociation (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

EXAMINING DISSOCIATION IN PRESCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN

There are few studies of dissociation involving preschool-age children, despite indications that dissociation has profound effects on early childhood development (Hornstein, 1993). Most research has instead retrospectively examined the impact of child maltreatment on dissociation in adulthood, perhaps because of the challenges involved with assessing pathological dissociation in young children. Preschoolers typically have higher levels of normative dissociation as compared to other age groups and can enter a trance-like state when distressed (Putnam, 1997). The assessment of dissociation in preschoolers, therefore, must examine the frequency, pervasiveness, and disruptiveness of symptoms, taking into account what is age appropriate (Hornstein, 1993).

Macfie, Cicchetti, and Toth (2001) examined dissociation in a sample of preschool-age children using the Child Dissociative Checklist (CDC; Putnam, Helmers, & Trickett, 1993). They grouped subtypes of maltreatment using a hierarchical system based on deviation from social norms, in which the sexual abuse category included children who had also experienced physical abuse or neglect, the physical abuse category included children who had also experienced neglect, and the neglect category included only children who had been neglected. Children in each of these categories demonstrated significantly more dissociation than nonmaltreated children. Severity and chronicity of maltreatment were also associated with dissociation. Of the maltreatment subgroups, only the physical abuse category was significantly associated with scoring in the clinical range on the CDC. This is a noteworthy finding, as dissociation has commonly been associated with sexual abuse, at least in adult samples (e.g., Kisiel & Lyons, 2001). Indeed, many studies have demonstrated a relationship between sexual abuse and later dissociation, whereas the association between physical abuse and later dissociation has been less consistent (e.g., Briere & Runtz, 1988; Coons, 1996; Hornstein & Putnam, 1992; Irwin, 1994; Kirby, Chu, & Dill, 1993; Sanders & Giolas, 1991; Waldinger, Swett, Frank, & Miller, 1994; Zlotnick et al., 1996).

In a longitudinal study of at-risk children, Ogawa, Sroufe, Weinfeld, Carlson, and Egeland (1997) measured dissociation at different developmental stages including the preschool period. To do so, the authors created a Dissociation subscale using items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the CBCL Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991) that correspond to CDC items (see Table 1). Ogawa et al. found that maltreatment predicted dissociation across developmental periods (i.e., infancy, preschool, elementary school, adolescence, and young adulthood). Significant predictors of dissociation during the toddler/preschool period included prior experiences of physical abuse or neglect during infancy, and concurrent sexual abuse (Ogawa et al., 1997). The findings by Ogawa et al. as well as Macfie et al. (2001) therefore suggest that dissociation may be a developmentally valid response to the experience of physical abuse in early childhood.

TABLE 1.

Items from all CBCL subscales.

| Malinosky-Rummel & Hoier (1991) | |

| Dissociation | |

| 1. | Acts too young for his/her age |

| 5. | Behaves like opposite sex |

| 8. | Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long |

| 13. | Confused/Seems to be in a fog |

| 17. | Daydreams or gets lost in thoughts |

| 80. | Stares blankly |

| 87. | Sudden changes in mood or feelings |

| Ogawa et al. (1997) | |

| Dissociation | |

| 1. | Acts too young for his/her age |

| 8. | Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long |

| 13. | Confused/Seems to be in a fog |

| 17. | Daydreams or gets lost in thoughts |

| 18. | Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide |

| 36. | Gets hurt a lot, accident prone |

| 40. | Hears sounds/voices that aren’t there |

| 80. | Stares blankly |

| 87. | Sudden changes in mood or feelings |

| 91. | Talks about killing self |

| Hulette et al. (in press) | |

| Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion | |

| 9. | Can’t get mind off certain thoughts |

| 18. | Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide |

| 29. | Fears certain animals, situations, places |

| 45. | Nervous/highstrung/tense |

| 47. | Nightmares |

| 50. | Too fearful or anxious |

| 66. | Repeats certain acts over and over |

| 84. | Strange behavior |

| 100. | Trouble sleeping |

| Sim et al. (2005) | |

| Dissociation | |

| 13. | Confused/Seems to be in a fog |

| 17. | Daydreams or gets lost in thoughts |

| 80. | Stares blankly |

| PTSD | |

| 9. | Can’t get mind off certain thoughts |

| 29. | Fears certain animals, situations, places |

| 45. | Nervous/highstrung/tense |

| 47. | Nightmares |

| 50. | Too fearful or anxious |

| 76. | Sleeps less than other children |

| 100. | Trouble sleeping |

| PTSD/ Dissociation | |

| 8. | Can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long |

| 9. | Can’t get mind off certain thoughts |

| 13. | Confused/Seems to be in a fog |

| 17. | Daydreams or gets lost in thoughts |

| 29. | Fears certain animals, situations, places |

| 40. | Hears sounds/voices that aren’t there |

| 45. | Nervous/highstrung/tense |

| 47. | Nightmares |

| 50. | Too fearful or anxious |

| 66. | Repeats certain acts over and over |

| 76. | Sleeps less than other children |

| 80. | Stares blankly |

| 84. | Strange behavior |

| 87. | Sudden changes in mood or feelings |

| 92. | Talks or walks in sleep |

| 100. | Trouble sleeping |

A number of other recent studies have assessed dissociation as well as PTSD in children by using items from the CBCL (see Table 1). Inasmuch as the CBCL is a widely used behavioral assessment tool, scales derived from this measure could greatly expand the number of studies of child trauma. However, many of the symptoms associated with these types of pathology are difficult to observe and report, and it is important to note that the CBCL was not originally designed to measure dissociation or PTSD.

Malinosky-Rummel developed a six-item CBCL Dissociation subscale that corresponds with items from the CDC (Malinosky-Rummel & Hoier, 1991). The subscale was originally used to measure dissociation in a sample of 7- to 12-year-olds. Although the authors demonstrated that the CBCL Dissociation subscale had adequate item generalizability, Malinosky-Rummel and Hoier did not use it to distinguish between maltreated and nonmaltreated groups. More recently, Sim and colleagues (2005) developed a 7-item PTSD subscale, a 3-item Dissociation subscale, and a 16-item PTSD/Dissociation subscale. These subscales were created using CBCL item ratings by clinical child psychology experts. Sim et al. used the scales to examine dissociation and PTSD in a sample of 4- to 12-year-olds, comparing normative, psychiatric, and sexually abused samples. Findings showed that the psychiatric and sexually abused groups had significantly higher levels of dissociation and PTSD than the normative sample, although the subscales did not distinguish between the clinical samples themselves.

Although the CBCL dissociation subscales described previously contain certain core items, there are also items unique to each subscale. Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) examined the adequacy of these different scales, as well as discriminant validity between dissociation and PTSD symptomatology. The authors used CBCL data from a sample of 177 maltreated preschool-age foster children that were part of a randomized trial of a therapeutic foster care intervention (Fisher, Burraston, & Pears, 2005). Items from the Malinosky-Rummel and Hoier (1991), Ogawa et al. (1997), and Sim et al. (2005) CBCL subscales were pooled, and each item was then individually assessed for face validity for either dissociation or PTSD. Once items for each construct were selected, a data reduction process was employed to systematically improve the level of internal consistency of these groups of items as measured by Cronbach’s alpha. Two scales emerged: one scale with items identical to the Sim et al. Dissociation subscale and one scale of posttraumatic hyperarousal/intrusion symptoms. A confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the adequacy of model fit for these two scales.

Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) used these subscales to assess the impact of maltreatment on dissociation and PTSD symptoms in foster preschoolers. Analyses indicated that these children had significantly higher levels of both types of symptoms as compared to nonmaltreated children. The authors also examined differences between children with specific maltreatment profiles, which had been identified using latent profile analysis in a prior study (Pears, Kim, & Fisher, in press). Four profiles were compared:

Supervisory neglect/emotional maltreatment: moderate- to high-severity levels of supervisory neglect and emotional maltreatment but low levels of physical neglect (e.g., failure to provide food and medical care) and almost no physical or sexual abuse.

Sexual abuse/emotional maltreatment/neglect: high levels of sexual abuse and emotional maltreatment, moderate levels of neglect, and almost no physical abuse.

Physical abuse/neglect/emotional maltreatment: moderate- to high-severity levels of physical abuse in addition to neglect and emotional maltreatment but very low levels of sexual abuse.

Sexual abuse/physical abuse/emotional maltreatment/neglect: all of the maltreatment types experienced at moderate to high levels.

Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) found that children who had experienced high-severity sexual abuse with emotional maltreatment/neglect had a significantly higher mean level of PTSD symptomatology than both the group that had experienced moderate- to high-severity physical abuse with emotional maltreatment/neglect and the group that had primarily experienced only emotional maltreatment/neglect. In contrast, the highest dissociation levels were found in children who experienced moderate- to high-severity physical abuse with emotional maltreatment/neglect. Children in this group were significantly different from those who primarily experienced emotional maltreatment/neglect. These findings were in line with those from the Macfie et al. (2001) study, in which high levels of dissociation were found among physically abused preschool-age children.

CURRENT STUDY

Although replication of new research findings is commonly acknowledged as important to the advancement of knowledge, this step is often overlooked in the social sciences. This is problematic, because results may be affected by idiosyncrasies of a particular sample and thus may not be generalizable. Thus, the first goal of the current study was to test whether the dissociation and posttraumatic arousal/intrusion CBCL scales from our prior work could be replicated (Hulette et al., in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007). A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the factor structure on a new data set of maltreated foster children. The second goal of the study was to compare dissociation and posttraumatic symptomatology across maltreatment subgroups. Although we did not have information on maltreatment severity, we created groups that were similar to those in the Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) study: children who experienced sexual abuse alone or with neglect/emotional maltreatment, children who experienced physical abuse alone or with neglect/emotional maltreatment, children who experienced both sexual and physical abuse and possible neglect/emotional maltreatment, and children who experienced neglect/emotional maltreatment only. Based on research by Ogawa et al. (1997), Macfie et al. (2001), and Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007), we hypothesized that preschoolers who had experienced physical abuse, either alone or in addition to other maltreatment subgroups, would exhibit high dissociation levels. We also hypothesized that preschool- age children who had experienced physical and sexual abuse might be likely to have higher levels of dissociation than other subgroups because of a greater need for a coping mechanism. Children who had experienced sexual abuse alone or with neglect/emotional maltreatment were expected to have high levels of posttraumatic symptomatology, as demonstrated in the Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) study.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were children who entered new foster placements between May 1990 and October 1991 in San Diego, California. They were part of the Foster Care Mental Health (FCMH) study conducted by the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center, San Diego, CA. To be included in the FCMH study, children needed to have remained in their foster placements for at least 5 months. This cohort of children included youth aged 0 to 17 (n = 1,221); however, interview data were only obtained for 78% of the total group (n = 934). The mean age of the sample was 7.6 years (SD = 4.2), and 55% of the sample was female. The racial/ethnic distribution was as follows: 45% Caucasian, 32% African American, 19% Latino, and 4% Asian American and other minorities. The breakdown of living situations was as follows: 31% in kinship foster care, 63% in foster care, and 6% in alternative residential placements such as group homes. At the time of data collection, the mean number of months in out-of-home placement was 7.9 (SD = 3.1), and the mean number of months living with the caretaker informant was 6.6 (SD = 7.4).

Children younger than age 4 were excluded from the present study because the scales used were derived from the CBCL for ages 4 to 18. Children older than age 11 were also excluded; this was done in order to make the study consistent with prior studies of CBCL subscales that did not include adolescents (e.g., Malinosky-Rummel & Hoier, 1991; Sim et al., 2005). We performed a confirmatory factor analysis of the CBCL scales with the resulting sample (n = 306). To examine differences in dissociation and posttraumatic symptomatology in preschoolers, we selected a smaller subset of children aged 4 to 6 (n = 139).

Maltreatment Coding

The maltreatment experiences of the children in the study were coded from Department of Social Services case files (Garland, Landsverk, Hough, & Ellis-MacLeod, 1996). Coders used the petition that was filed in Juvenile Court within 48 hr of the child’s removal from the home to record the type of maltreatment for which there was sufficient evidence to place the child in protective custody. Other types of substantiated maltreatment were also coded if mentioned in the petition. The data therefore do not necessarily reflect the child’s comprehensive maltreatment history. Types of maltreatment included the following (Garland et al., 1996): sexual abuse (sexual assault of the child), physical abuse (physical injury to the child), neglect (including lack of supervision, inability to provide basic needs, or medical/educational neglect), emotional abuse (including exposure to domestic violence, verbal abuse, or unreasonable/cruel restraint of child), other abuse (including exploitation), and caretaker absence (parental physical or psychological incapacity, parent incarceration, and missing parents).

Several steps were taken to create groups that were comparable to those used in the Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) study. In each of the four Pears et al. (in press) maltreatment profiles, emotional maltreatment and neglect clustered together. Because the other abuse maltreatment type included forms of emotional maltreatment and there were few cases of emotional abuse, we combined the neglect, emotional abuse, and other abuse variables into an overall neglect maltreatment type. The caretaker absence variable was excluded from analyses because it was not sufficiently similar to maltreatment variables in the prior study. Thus, the three individual maltreatment types used in the current study were (a) sexual abuse, (b) physical abuse, and (c) overall neglect.

For each maltreatment type, participants were coded as “no,” “yes,” or “protective issue.” A code of protective issue indicated that there was no direct evidence that the child was maltreated but that he or she was removed to protect against the possibility of that type of maltreatment (e.g., sibling was physically abused). As participants might have experienced multiple forms of maltreatment, we created the following maltreatment groups: sexual abuse, which may also have included neglect and/or protective issues (n = 48; 15.7% of sample); physical abuse, which may also have included neglect and/or protective issues (n = 102; 33.3% of sample); multiple types of maltreatment, referring to the experience of sexual and physical abuse, and which may have included neglect and/or protective issues (n = 22; 7% of sample); and neglect only, referring to children who did not have documented sexual or physical abuse and may have been in care for protective issues (n = 134; 43.8% of sample).

Because the current study was a replication of our prior work, these patterns were created to approximate the groups in our previous studies. However, it should be noted that there were some differences. In particular, severity information was unavailable for this study. Equally important, subtypes of neglect—such as physical neglect (e.g., failure to provide adequate food, shelter, or medical care) and supervisory neglect (e.g., lack of age-appropriate supervision)—were not initially coded as separate variables and therefore were not differentiated in this study.

Measures

CBCL subscales

The CBCL is a 113-item behavior rating scale for children aged 4 to 18, for which reliability and validity is well established (Achenbach, 1991). Caregivers rate their child’s behavior over the prior 6 months on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true/sometimes true), and 2 (very true/often true). Dissociation and posttraumatic symptoms were assessed using two CBCL subscales.

The first subscale (Dissociation) was developed by Sim et al. (2005). This subscale was used in the Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) study. The subscale was created through a process involving item ratings by a panel of 16 clinical child psychology experts. An item was included in the Dissociation subscale if at least two thirds of experts rated the item as indicative of the construct. Sim et al. performed a confirmatory factor analysis and found a coefficient alpha of .71.

The second subscale (Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale) was developed by Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007). In that study, a confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated good model fit of the Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale in addition to the Sim et al. (2005) Dissociation subscale. Cronbach’s alphas were .78 for the Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale and .85 for the Dissociation subscale (Hulette et al., in press).

Data Analysis Strategies

Dissociation and Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale scores for children aged 4 to 11 were produced by summing items and creating average scores. The Dissociation subscale (Sim et al., 2005) had a Cronbach’s alpha value of .709, and the Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale (Hulette et al., in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) had a Cronbach’s alpha value of .705, indicating high internal consistency of items. The two subscales were positively correlated (r = .47, p < .01).

To test the replication of these scales, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis on the FCMH data set. This allowed us to examine the factor structure of these two subscales in an independent sample. Following the confirmatory factor analysis, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to compare dissociation and posttraumatic symptomatology across maltreatment subgroups.

RESULTS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The adequacy of the hypothesized factor structure was examined using Mplus 4.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). We used full information maximum likelihood with robust standard error estimators to take into account the interdependence of sibling data as well as the non-normality of items. This also allowed for the inclusion of participants with partial data on dependent variables. The residual errors of three pairs of items were allowed to covary: Item 100 (Trouble sleeping) with Item 47 (Nightmares), Item 50 (Too fearful or anxious) with Item 29 (Fears certain animals, situations, places), and Item 66 (Repeats certain acts over and over) with Item 9 (Can’t get mind off of certain thoughts). These item pairs were chosen because they were likely to have common sources of variance due to similar content and high correlations. In addition, items for each pair were located on the same factor.

Standardized and unstandardized coefficients, and critical ratios for the items, are presented in Table 2. All 13 items loaded significantly on the two latent factors, and the model fit the data well, χ2(61) = 77.889, p = 0.06, comparative fit index = 0.96, Tucker–Lewis Index = 0.95, root mean square error of approximation = 0.03, standardized root-mean-square residual = 0.045.

TABLE 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

| Item | Standardized β |

Unstandardized β |

Critical Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sim et al. (2005) Dissociation Subscale | ||||

| 13. | Confused/Seems to be in a fog | 0.731 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| 17. | Daydreams or gets lost in thoughts | 0.672 | 0.889 | 7.211 |

| 80. | Stares blankly | 0.607 | 0.678 | 6.207 |

| Hulette et al. (in press) Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale | ||||

| 9. | Can’t get mind off certain thoughts | 0.473 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| 18. | Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide | 0.306 | 0.293 | 3.442 |

| 29. | Fears certain animals, situations, places | 0.232 | 0.501 | 2.537 |

| 45. | Nervous/highstrung/tense | 0.634 | 1.336 | 5.564 |

| 47. | Nightmares | 0.282 | 0.454 | 3.641 |

| 50. | Too fearful or anxious | 0.547 | 0.984 | 4.963 |

| 66. | Repeats certain acts over and over | 0.381 | 0.740 | 4.970 |

| 84. | Strange behavior | 0.514 | 0.928 | 4.702 |

| 87. | Sudden changes in mood or feelings | 0.633 | 1.330 | 5.268 |

| 100. | Trouble sleeping | 0.225 | 0.347 | 3.255 |

ANOVA Comparisons Using CBCL Subscales

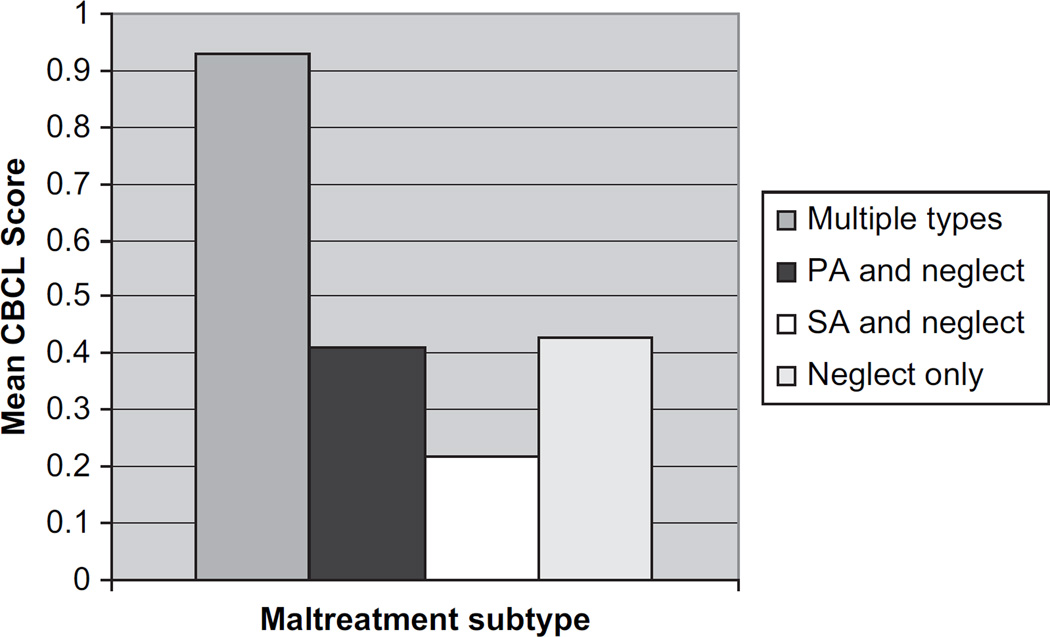

One-way ANOVAs were conducted on the subset of preschoolers (n = 139) to compare scores of the maltreatment subgroups on the Dissociation subscale and the Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale. Means and standard deviations for the four maltreatment subgroups are presented in Table 3: sexual abuse and neglect (n = 20), physical abuse and neglect (n = 47), multiple types of maltreatment (n = 10), and neglect only (n = 62).

TABLE 3.

Descriptive statistics of maltreatment subgroups.

| Scale | All Types | Physical Abuse and Neglect |

Sexual Abuse and Neglect |

Neglect Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Dissociation | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion |

0.53 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.36 |

Each outlier was recoded to be within two standard deviations of the mean. Tests of homogeneity of variance were run due to unequal cell sizes; however, neither subscale was significant at the .05 level. ANOVAs (see Figure 1) indicated that the groups differed significantly on the Dissociation subscale, F(3, 135) = 5.384, p = .002, η2 = 0.107. Tukey’s honestly significant difference test revealed that the group that had experienced multiple types of maltreatment (M = 0.93, SD = 0.44) had a significantly higher mean dissociation level than all three other groups (see Table 4). The Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale did not show significant differences between maltreatment subgroups, F(3, 135) = 0.627, p = .559.

FIGURE 1.

Differences in Dissociation Levels in Maltreatment Subgroups CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; PA = Physical Abuse; SA = Sexual Abuse

TABLE 4.

Results of post hoc comparison.

| Dependent Variable |

(I) Maltreatment | (J) Maltreatment |

M Difference (I – J) |

SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Subscale |

Multiple Types | Sexual Abuse With Neglect |

0.7141 | 0.1787 | .001 |

| Physical Abuse With Neglect |

0.5209 | 0.1607 | .008 | ||

| Neglect Only | 0.5067 | 0.1572 | .009 |

DISCUSSION

A confirmatory factor analysis successfully replicated the factor structure of dissociation and posttraumatic arousal/intrusion symptoms from our prior study (Hulette et al., in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007), suggesting that dissociation and PTSD symptomatology are observable as discrete traumatic sequelae among preschool-age foster children and underscoring the importance of assessing maltreated preschoolers for both types of psychopathology.

As there is a lack of research on these constructs in young children, we were also interested in examining whether children with empirically derived maltreatment profiles had differential levels of each type of psychopathology. We found that preschool-age children who experienced sexual and physical abuse as well as possible neglect had significantly higher levels of dissociation than all other groups observed in the study. Thus, although the literature has placed a strong emphasis on the relationship between dissociation and sexual abuse, and sexual abuse may indeed be a potential contributing factor, our findings emphasize the role of multiple types of maltreatment in the development of dissociation. This is consistent with research by Pears et al. (in press), who found that children who had experienced sexual and physical abuse in addition to neglect had the worst outcomes on measures of internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and cognitive delays. Thus, experiencing a range of different types of maltreatment appears to put children at greater risk for multiple problems. With respect to dissociation in particular, these children may have the greatest need to block out the distress of abuse. However, it is possible that children who have experienced multiple types of abuse and are now in foster care score highly on this measure of dissociation because the amount of chaos in their lives has led to poor attention regulation. It is also likely that dissociation in foster children, for whom abuse histories are public, is qualitatively distinct from dissociation in samples with ongoing, secretive abuse; this should be explored in future research.

Finklehor, Ormrod, and Turner (2007) found that the experience of multiple forms of victimization (i.e., maltreatment, crime, sexual victimization, peer/sibling victimization, witnessed victimization), or poly-victimization, was highly predictive of trauma symptoms and greatly reduced or even eliminated the association between individual victimization type and symptomatology in many cases. However, the experience of maltreatment made an independent contribution to trauma symptoms over and above what could be accounted for by poly-victimization (Finkelhor et al., 2007). This indicates that maltreatment, compared to other traumas, has a strong negative impact on the child. Furthermore, it suggests the importance of considering subgroups of maltreatment in understanding traumatic sequelae; perhaps the concept of poly-victimization can be extended to maltreatment, as it seems that experiencing multiple forms of maltreatment is damaging.

The findings in the current study are discrepant from those by Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007), in which children who were primarily physically abused at moderate to high severity levels had the highest levels of dissociative symptoms. However, in that study, those physically abused children were not significantly different from children who had experienced multiple types of maltreatment at moderate to high severity. The lack of maltreatment severity information in the current study may explain the discrepancy. For instance, children in the current study who experienced primarily sexual abuse, physical abuse, or neglect may have been exposed to low severity levels of each type, whereas the children who experienced multiple types of maltreatment may have been exposed to high severity levels. Severity of maltreatment may therefore be a decisive factor in the development of dissociation. This might also explain why no differences between groups were observed on the Posttraumatic Arousal/Intrusion Symptomatology Subscale.

There was also a lack of differentiation between subtypes of neglect used in the current study. The FCMH data were initially coded in a way that grouped physical neglect (e.g., failure to provide adequate food, shelter, or medical care) with supervisory neglect (e.g., lack of age-appropriate supervision). Pears et al. (in press) found at least one distinct maltreatment profile for which there were high levels of supervisory neglect and low levels of physical neglect, indicating that neglect subtypes might be important to include in analyses. Another possible explanation for the discrepancy between studies is that we did not have CBCL data for 3-year-olds. The Hulette et al. (in press; see also Cholankeril et al., 2007) study included 3-year-olds, who may have developmentally different responses to the experience of different types of maltreatment.

In general, further research will be important in clarifying the relationship between maltreatment and dissociation during the preschool years. A limitation to this work is that we have not yet established convergent validity of the Dissociation subscale to a valid and reliable measure of childhood dissociation such as the CDC. It is therefore important to take caution in the interpretation of these results. A second major limitation is the lack of comprehensive information about the children’s maltreatment histories. Maltreatment types were coded using the petition filed by the Department of Social Services to place the child in protective custody, and it is likely that some of the children experienced other types of abuse that were not recorded on the petition. That said, it is generally difficult to ascertain accurate information on maltreatment experiences with young children. Children may be reluctant or unable to reveal their abuse history or may have amnesia for traumatic events due to their need to maintain an attachment to the abusive caregiver (Freyd, 1996).

Overall, the current study provides evidence that the experience of trauma is related to dissociative tendencies in preschool-age children. Although these symptoms may help children cope with abuse, research indicates that dissociation is related to long-term maladaptation in various domains (Putnam, 1997). It is therefore essential to understand the mechanisms underlying the development of dissociation in early childhood so as to prevent long-term pathology in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their participants and colleagues at the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center in San Diego, the Oregon Social Learning Center, and the Freyd Dynamics Lab at the University of Oregon.

Support for this research was provided by the following grants: DA021424 and DA017592 (National Institute on Drug Abuse) and MH059780 (National Institute of Mental Health).

Contributor Information

Annmarie C. Hulette, University of Oregon.

Philip A. Fisher, Oregon Social Learning Center.

Hyoun K. Kim, Oregon Social Learning Center.

William Ganger, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center.

John L. Landsverk, Child and Adolescent Services Research Center.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide to the 1991 CBCL/4– 18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. text rev. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Child abuse trauma: Theory and treatment of the lasting effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Runtz M. Symptomatology associated with childhood sexual victimization in an adult clinical sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1988;12:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholankeril A, Freyd JJ, Becker-Blease KA, Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA. Dissociation and post-traumatic symptoms in maltreated preschool children. Poster presented at the 115th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA; 2007. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 1993;56(1):96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coons PM. Clinical phenomenology of 25 children and adolescents with dissociative disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1996;5:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Burraston B, Pears K. The Early Intervention Foster Care Program: Permanent placement outcomes from a randomized trial. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:61–71. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Landsverk JL, Hough RL, Ellis-MacLeod E. Type of maltreatment as a predictor of mental health service use for children in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein NL. Complexities of psychiatric differential diagnosis in children with dissociative symptoms and disorders. In: Silberg JS, editor. The dissociative child: Diagnosis, treatment, and management. Baltimore: Sidran Press; 1993. pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein NL, Putnam FW. Clinical phenomenology of child and adolescent dissociative disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:1077–1085. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulette AC, Freyd JJ, Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA, Becker-Blease KA. Dissociation and post-traumatic symptomatology in maltreated preschool children. Journal of Child and Adolescant Trauma. doi: 10.1080/19361520802083980. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin HJ. Proneness to dissociation and childhood traumatic events. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182:456–460. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199408000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JS, Chu JA, Dill DL. Correlates of dissociative symptomatology in patients with physical and sexual abuse histories. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34(4):258–263. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90008-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel CL, Lyons JS. Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1034–1039. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotti G. Disorganization of attachment as a model for understanding dissociative psychopathology. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 291–317. [Google Scholar]

- Macfie J, Cicchetti D, Toth S. Dissociation in maltreated versus nonmaltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinosky-Rummel RR, Hoier TS. Validating measures of dissociation in sexually abused and nonabused children. Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:341–357. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers. User’s guide. 3rd. Los Angeles: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa JR, Sroufe LA, Weinfeld NS, Carlson EA, Egeland B. Development and the fragmented self: Longitudinal study of dissociative symptomatology in a nonclinical sample. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:855–879. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA. Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW. Dissociation in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW, Helmers K, Trickett PK. Development, reliability, and validity of a child dissociation scale. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17:731–741. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(08)80004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders B, Giolas MH. Dissociation and childhood trauma in psychologically disturbed adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:50–54. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.3.A50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Friedrich WN, Hobart Davies W, Trentham B, Lengua L, Pithers W. The Child Behavior Checklist as an indicator of posttraumatic stress disorder and dissociation in normative, psychiatric, and sexually abused children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:697–705. doi: 10.1002/jts.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terr L. Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:10–19. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Swett C, Frank A, Miller K. Levels of dissociation and histories of reported abuse among women outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182:625–630. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Shea MT, Pearlstein T, Begin A, Simpson E, Costello E. Differences in dissociative experiences between survivors of childhood incest and survivors of assault in adulthood. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184:52–54. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]