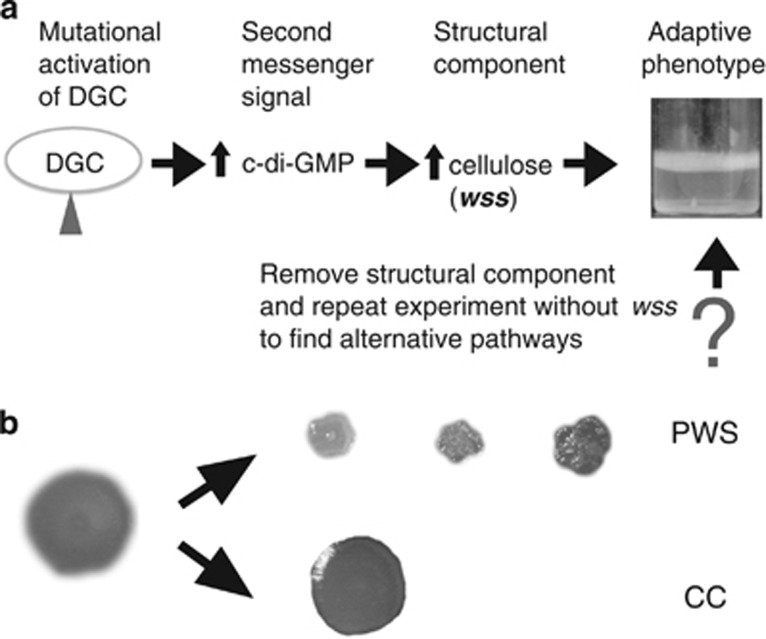

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental evolution of adaptive divergence in P. fluorescens SBW25. Strong selection for access to oxygen in static microcosms leads to the invasion of mutants that colonise the air–liquid interface. In wild-type P. fluorescens SBW25, wrinkly spreader (WS) mutants repeatedly evolve through mutations activating diguanylate cyclases (DGCs), which in turn activates production of the structural component cellulose, encoded by the wss operon. By removing the genes encoding the cellulose biosynthetic machinery we address the question as to whether there exists alternative structural components for mat formation at the air–liquid interface. (b) Alternative adaptive air–liquid colonising mutants. Two new types of mutants were found after experimental evolution in static microcosms. Colony morphologies on Congo Red agar revealed one type (PWS) that strongly binds Congo Red and has a wrinkled morphology and one type more similar to the ancestral strain (CC).