Abstract

Introduction:

Pleural empyema as a focal infection due to Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis is rare and most commonly described among immunosuppressed patients or patients who suffer from sickle cell anaemia and lung malignancies.

Case presentation:

Here, we present an 81-year-old immunocompetent Greek woman with bacteraemia and pleural empyema due to Salmonella Enteritidis without any gastrointestinal symptoms.

Conclusion:

In our case, we suggest that patient’s pleural effusion secondary to heart failure was complicated by empyema and that focal intravascular infection was the cause of bacteraemia.

Keywords: Salmonella Enteritidis, focal Salmonella Enteritidis infections, pleural empyema, dyspnea, ciprofloxacin

Introduction

Salmonellae belong to the family Enterobacteriaceae and are motile Gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacilli. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis mostly causes enterocolitis. Localised infections include gastroenteritis, osteomyelitis, nephritis, cholecystitis, endocarditis, meningitis and pneumonia. Pleural empyema is a rare localised infection due to bacteraemia from Salmonella Enteritidis and is usually associated with underlying immunodeficiency, sickle cell anaemia and lung cancer (Mandell et al., 2010). Here, we present the case of an 81-year-old immunocompetent Greek female patient, who was diagnosed with pleural empyema due to Salmonella Enteritidis without any gastrointestinal symptoms, and we review the literature regarding bacteraemia and focal infections due to nontyphoidal Salmonellae.

Case report

An 81-year-old Greek female patient with medical history significant for congestive heart failure, mild pulmonary hypertension, hypertension, atrial fibrillation and stroke in 2013 attended the Emergency Department of the University General Hospital of Patras due to dyspnoea and coughing for a week. She reported a single episode of fever 38 °C and chills 10 days before admission. No diarrhoea or symptoms related to gastrointestinal tract were reported. There was no former medical history of pulmonary disease or sickle cell anaemia.

The vital signs on admission were as follows: blood pressure of 137/60 mmHg, pulse rate of 81 beats/min, temperature of 37 °C and oxygen saturation of 78 % (FiO2 : 21 %). Physical examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness to percussion over the right lung base. The abdomen was soft on palpation without tenderness and there was lower extremities edema. The initial laboratory findings showed white blood cell count of 19.340 cells mm−3, with 83 % neutrophils, elevated C-reactive protein levels (34.3 U l−1, normal values <0.8 U l−1) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 118 mm in the first hour (normal values 0–20 mm). On admission, both renal and liver function parameters were elevated [blood urea 92 mg dl−1 (normal values 15–54 mg dl−1), creatinine 1.8 mg dl−1 (normal values 0.9–1.6 mg dl−1), aspartate aminotransferase 89 U l−1 (normal values 5–40 U l−1) and alanine aminotransferase 48 U l−1 (5–40)]. All these values dropped within normal range after treatment (blood urea 41 mg dl−1, creatinine 1.4 mg dl−1, aspartate aminotransferase 38 U l−1 and alanine aminotransferase 32 U l−1.

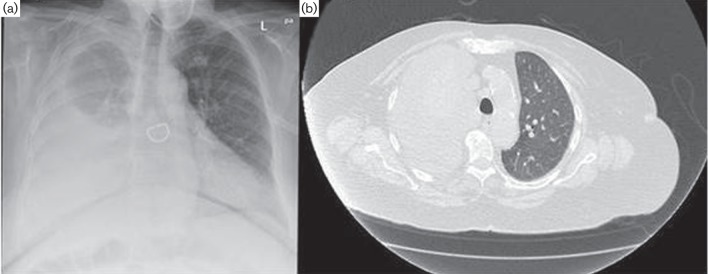

Posteroanterior chest X-ray (Fig. 1a) and computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1b) showed a large right-sided pleural effusion partially encapsulated with lung atelectasis and a few in number up to 1.5 cm lymph nodes in the mediastinum. A diagnostic thoracocentesis was performed, which revealed a turbid exudative pleural fluid with the following parameters: pH: 7.5, specific weight: 1010, 1956 leukocytes/mm3 (64 % polymorphonuclear cells, 33 % lymphocytes and 3 % monocytes), 14 080 red blood cells/mm3, glucose 3.0 mg d l−1 (serum glucose 99 mg dl−1), lactate dehydrogenase 1769 U l−1 (serum lactate dehydrogenase 420 U l−1) and proteins 5.1 g dl−1 (serum proteins 7.8 g dl−1).

Fig. 1.

Patient’s chest X-ray (a) and CT scan (b) showing a large right-sided pleural effusion with lung atelectasis.

Investigations

Further testing towards any possible associated immunodeficiency including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, serum globulin levels, full panel of serum tumour markers and glycosylated haemoglobin levels was unrevealing. Cytological pleural fluid analysis turned out to be negative for presence of malignant cells. In addition, no focal infection was identified in the gastrointestinal tract, heart and bones, according to results of abdominal CT scan, transthoracic echocardiography and bone scan, respectively. No stool culture was performed.

Diagnosis

Samples of the pleural fluid were sent for culture and cytological analysis. On admission and during hospitalisation, blood cultures were also obtained. Blood and pleural fluid samples were inoculated into BAC/TAlert 3D (bioMerieux) blood aerobic culture bottles. Identification of the culpable microorganism was performed by Vitek® 2 Advanced Expert System (bioMerieux), whereas antibiotic susceptibility testing by the disk diffusion method for ceftriaxone and a gradient method (Etest, bioMerieux) for ciprofloxacin was according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines (www.eucast.org). Serotyping was performed in all recovered isolates by polyvalent antisera (Statens Serum Institute). Both blood and pleural fluid cultures were positive for S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (AgO: 1, 9, 12).

Treatment

Susceptibility testing showed susceptibility to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin (MIC=0.008 mg l−1). According to these results, the patient was treated with ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 h intravenously for a period of 10 days. Moreover, a chest tube was placed and 1.5 l of pleural fluid was drained.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 h for 10 additional days after intravenous hospital therapy and recovered without complications. Follow-up blood cultures became negative after 7 days of treatment. No additional cultures of the pleural fluid after drainage were performed.

Discussion

The clinical syndromes caused by Salmonellae in descending order of frequency include gastroenteritis, enteric fever, bacteraemia and localised infections. There is also the chronic carrier state that involves 0.2–0.6 % of the patients with nontyphoidal Salmonella infection. Salmonella Enteritidis typically causes gastroenteritis (Mandell et al., 2010).

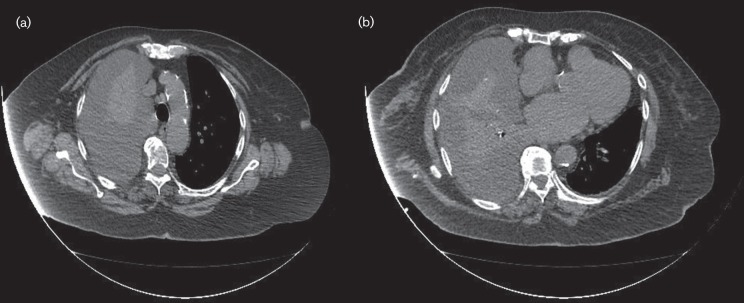

Bacteraemia develops in up to 8 % of patients with nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis and focal infection occurs mainly in infants, the elderly and patients with immunodeficiency. In contrast to children, focal infections due to primary bacteraemia are reported among adult patients and are related to increased mortality rates. In the elderly, Salmonellae invade atherosclerotic plaques and aneurysms during bacteraemia with a mortality rate up to 60 % (Mandell et al., 2010). In our case, atherosclerosis was evident and based on the presence of calcified atherosclerotic plaques of the aortic arch and descending aorta, as shown in Fig. 2(a, b), respectively.

Fig. 2.

Patient’s CT scan showing the presence of calcified atherosclerotic plaques of the aortic arch (a) and descending aorta (b).

Primary Salmonella bacteraemia in combination with atherosclerotic plaques invasion seems a possible explanation as the mechanism of infection in our case. Our patient was elderly, with no symptoms from gastrointestinal tract prior to infection. Very few data are available on heart failure being a risk factor for Salmonella empyema. de Lope et al. reported a case of a 54-year-old patient suffering from mitral valvulopathy and left-sided ventricular failure who presented with Salmonella empyema (de Lope et al., 2004). The annual incidence rate in patients above 50 years old with endovascular infection due to notyphoidal Salmonellae is 4.4 per 1 000 000 persons. Most of the patients reported in this group had a history of significant mycotic aneurysms or structural heart disease (Nielsen et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012; Ortiz et al., 2014). Our patient had no history of valvulopathy or other structural heart disease, whereas no aneurysms were detected.

Salmonella Enteritidis extraintestinal focal infection is most commonly presented among immunosuppressed patients or patients with sickle cell anaemia (Table 1). Among humans with mutations in the genes encoding the IFN-γ and IL-12 receptor, or patients who undergo treatment with TNF inhibitors, bacteraemia due to nontyphoidal Salmonella is grave (Mandell et al., 2010). Our patient had no medical history for sickle cell anaemia and there were no signs of defect in the IFN-γ and IL-12 receptor since there were no infections due to Mycobacteria or other intracellular bacteria during her childhood or afterwards. However, no tests were performed to examine IFN-γ and IL-12 receptor expression in our patient.

Table 1. Reported cases of pleural empyema caused by non typhoidal Salmonella.

| Author | Number of patients reported | Isolated microorganism | Underlying disease | Type of the infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buscaglia, 1978 | 1 | Salmonella Newport | Splenic abscess | Pleural empyema |

| Chaturvedi et al., 1978 | 1 | Salmonella Newport | Sickle cell disease | Pleural empyema |

| Kate et al., 1984 | 1 | Salmonella typhimurium | Alveolar cell carcinoma | Pleural empyema |

| Santus et al., 1984 | 1 | Salmonella cholera suis | Metastasizing breast cancer | Pleural empyema |

| Ortiz et al., 1991 | 1 | Salmonella Enteritidis | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pleural empyema |

| Gill et al., 1996 | 1 | Salmonella Enteritidis | Small cell bronchogenic carcinoma | Pleural empyema |

| Carel et al., 1977 | 1 | Nontyphoid Salmonella | Complication of a malignant pleural effusion in an immunocompromised patient | Pleural empyema |

| Wolday et al., 1997 | 1 | Salmonella Enteritidis | HIV | Pleural empyema |

| Roguin et al., 1999 | 1 | Salmonella Mendoza | Myelodysplastic syndrome | Pleural empyema |

| Ramanathan et al., 2000 | 2 | Salmonella Senftenberg | One patient with diabetes mellitus and the other one with gallbladder carcinoma | Pleural empyema |

| Rim et al., 2000 | 1 | Salmonella Group B | Diabetes mellitus | Pleural empyema |

| de Lope et al., 2004 | Salmonella Enteritidis | Age over 50 years old | Pleural empyema | |

| Crum et al., 2005 | 1 | Nontyphoid Salmonella | Immunosuppression | Pleural empyema |

| Takiguchi et al., 2008 | 1 | Salmonella Livingstone | Tuberculosis | Chronic empyema |

| Yang et al., 2008 | 1 | Nontyphoid Salmonella | A 26-year-old male patient, immunocompetent | Pleural empyema |

| Kam et al., 2012 | 1 | Group D Salmonella | Underlying pulmonary pathology, secondary to an extensive smoking history | Pleural empyema |

| Pathmanathan et al., 2015 | 1 | Salmonella typhimurium | Mild neutropenia (1.25×109 l−1) | Pleural empyema |

Salmonella is an intracellular pathogen, and it is well known that the final clearance of the infection depends on cellular immunity. Accordingly, diseases predisposing to extraintestinal Salmonella Enteritidis infection are AIDS, inflammatory bowel disease, lung and blood malignances (like leukaemia and lymphomas), diabetes mellitus, profound alcohol consumption, prolonged corticosteroid therapy and antineoplastic treatments (Table 1) (Rim et al., 2000; Mandell et al., 2010). It seems that 33.3 % of the HIV-infected patients diagnosed with Salmonella bacteraemia had focal lung infections (Casado et al., 1997; Fernandez-Guerrero et al., 1997; Persson et al., 2000; Samonis et al., 2003). Our patient proved to be negative for HIV serotypes 1 and 2. Moreover, blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin levels were normal and she did not prove to suffer from any malignancy. She was not consuming alcohol regularly and was not under corticosteroid or antineoplastic therapy.

The incidence of focal pulmonary infection due to Salmonella Enteritidis bacteraemia is very low and is regarded to be less than 1 % (Mandell et al., 2010). Salmonellae in the blood stream seem to have a tropism for abnormal tissues like malignant tumours, bone infarcts and aneurysms, whereas focal intravascular infection accounts for 25 % of patients over 50 years old (Khan et al., 1983; Samonis et al., 2003; Mandell et al., 2010). Despite pneumonia lung abscess, rarely pleural empyema, most commonly in patients with immunosuppression or underlying lung disease, has been described (Table 1) (Khan et al., 1983; Mandell et al., 2010; Kam et al., 2012). As mentioned above, our patient proved to be immunocompetent and did not suffer from lung disease.

Salmonella Enteritidis is reported to be a rare pathogen causing pleural empyema infection. Up to 2015, at about 17 cases of S. enterica empyema without pulmonary implication were published in Korea, USA, Spain, Japan, Italy, Ethiopia, Israel and India, as shown in Table 1 (Carel et al., 1977; Buscaglia, 1978; Chaturvedi et al., 1978; Kate et al., 1984; Santus et al., 1984; Ortiz et al., 1991; Gill et al., 1996; Wolday et al., 1997; Roguin et al., 1999; Ramanathan et al., 2000; Rim et al., 2000; de Lope et al., 2004; Takiguchi et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Kam et al., 2012; Crum et al., 2005; Pathmanathan et al., 2015). A case reported by Yang et al. (2008) refers to a 26-year-old immunocompetent male patient presented with nontyphoid Salmonella pleural empyema with previous history of pneumonia. To our knowledge, in Greece, there is only one report of S. enterica serotype Enteritidis pneumonia regarding a 72-year-old male patient with lung cancer in the island of Crete, in 2003. This was the first case of immunodeficient patient with Salmonella Enteritidis bacteraemia and empyema in Greece (Samonis et al., 2003). Our patient is the second case worldwide (de Lope et al., 2004) and the first in Greece, presented with pleural empyema caused by Salmonella Enteritidis in elderly patient with no severe underlying disease or pneumonia.

It has been reported that nontyphoid Salmonellae rest dormant in the reticuloendothelial system and blood spread is a consequence of reactivation. Moreover, due to low bacterial load, blood cultures are often negative. It has also been reported that Salmonellae seed atheromatic plaques and this can be the source of bacteraemia (Mandell et al., 2010; Pathmanathan et al., 2015). Our patient presented with lower extremities edema, dyspnoea and right-sided pleural effusion was already under treatment for congestive heart failure. These clinical findings support the suspicion that in this case Salmonella bacteraemia complicated a preexisting pleural effusion secondary to heart failure, as already reported (de Lope et al., 2004). In elderly patients with atherosclerosis and congestive heart failure, Salmonella bacteraemia must be considered a possible mechanism of pleural effusion dissemination. Even so, the incident of pleural empyema due to Salmonella Enteritidis is extremely low.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding of the Departments of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, University General Hospital of Patras, Greece.

Abbreviation:

- CT

computed tomography

References

- Buscaglia A. J.(1978). Empyema due to splenic abscess with Salmonella newport. JAMA 2401990. 10.1001/jama.1978.03290180064031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel R. S., Schey G., Ma'ayan M., Bruderman I.(1977). Salmonella empyema as a complication in malignant pleural effusion. Respiration 34232–235. 10.1159/000193830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado J. L., Navas E., Frutos B., Moreno A., Martín P., Hermida J. M., Guerrero A.(1997). Salmonella lung involvement in patients with HIV infection. Chest 1121197–1201. 10.1378/chest.112.5.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi P., Jain V. K., Gupta R. K., Saoji S., Moghe K. V., Sharma S. M.(1978). Sickle cell anaemia with Salmonella empyema thoracis: (a case report). Indian Pediatr 15605–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. L., Lee H. C., Lee N. Y., Wu C. J., Lin S. H., Shih H. I., Lee C. C., Ko W. C., Chang C. M.(2012). Non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteraemia in elderly patients: an increased risk for endovascular infections, osteomyelitis and mortality. Epidemiol Infect 1402037–2044. 10.1017/S0950268811002901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum N. F.(2005). Non-typhi Salmonella empyema: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 37852–857. 10.1080/00365540500264944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lope M. L., Batalha P., Sosa M., Rodríguez-Gómez F. J., Sánchez-Muñoz A., Pujol E., Aguado J. M.(2004). Pleural empyema due to Salmonella enteritidis in a non-immunocompromised patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 23792–793. 10.1007/s10096-004-1204-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Guerrero M. L., Ramos J. M., Núñez A., Cuenca M., de Górgolas M.(1997). Focal infections due to non-typhi Salmonella in patients with AIDS: report of 10 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 25690–697. 10.1086/513747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G. V., Holden A.(1996). A malignant pleural effusion infected with Salmonella enteritidis. Thorax 51104–105. 10.1136/thx.51.1.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam J. C., Abdul-Jawad S., Modi C., Abdeen Y., Asslo F., Doraiswamy V., Depasquale J. R., Spira R. S., Baddoura W., Miller R. A.(2012). Pleural empyema due to Group D Salmonella. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2012524561. 10.1155/2012/524561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kate P., Osei K., Chiemchanya S., Zatuchni J.(1984). Empyema due to Salmonella typhimurium with underlying alveolar cell carcinoma. South Med J 77234–236. 10.1097/00007611-198402000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan K., Chaudhary B. A., Speir W. A.(1983). Salmonella pneumonia. The Journal of IMA 15146–148. 10.5915/15-4-12423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell G. L., Bennett J. E., Dolin R.(2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 2nd edn, Churchil Livingstone Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H., Gradel K. O., Schønheyder H. C.(2006). High incidence of intravascular focus in nontyphoid Salmonella bacteremia in the age group above 50 years: a population-based study. APMIS 114641–645. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A., Giraldez D., Egido J., Fernández-Guerrero M.(1991). Salmonella enteritidis empyema complicating lupus pleuritis. Postgrad Med J 67778–779. 10.1136/pgmj.67.790.778-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz D., Siegal E. M., Kramer C., Khandheria B. K., Brauer E.(2014). Nontyphoidal cardiac salmonellosis: two case reports and a review of the literature. Tex Heart Inst J 41401–406. 10.14503/THIJ-13-3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathmanathan S., Welagedara S., Dorrington P., Sharma S.(2015). Salmonella empyema: a case report. Pneumonia 6120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson K., Mörgelin M., Lindbom L., Alm P., Björck L., Herwald H.(2000). Severe lung lesions caused by Salmonella are prevented by inhibition of the contact system. J Exp Med 1921415–1424. 10.1084/jem.192.10.1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan R. M., Aggarwal A. N., Dutta U., Ray P., Singh K.(2000). Pleural involvement by Salmonella senftenberg: a report of two cases. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 4231–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rim M. S., Park C. M., Ko K. H., Lim S. C., Park K. O.(2000). Pleural empyema due to Salmonella: a case report. Korean J Intern Med 15 138–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roguin A., Gavish I., Ben Ami H., Edoute Y.(1999). Pleural empyema with Salmonella mendoza following splenic abscesses in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J 1195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samonis G., Maraki S., Kouroussis C., Mavroudis D., Georgoulias V.(2003). Salmonella enterica pneumonia in a patient with lung cancer. J Clin Microbiol 415820–5822. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5820-5822.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santus G., Sottini C., Rozzini R.(1984). Pleural empyema due to Salmonella cholerae suis in patients with metastasizing breast cancer. Minerva Medica 751223–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi Y., Ishikawa S., Shinbo Y.(2008). A case of chronic empyema caused by Salmonella Livingstone with soft-tissue abscess. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 46191–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (2013). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 3.1 http://www.eucast.org. Accessed on 11 February 2016.

- Wolday D., Seyoum B.(1997). Pleural empyema due to Salmonella paratyphi in a patient with AIDS. Trop Med Int Health 21140–1142. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. Y., Kwak H. W., Song J. H., Jeon E. J., Choi J. C., Shin J. W., Kim J.-Y., Park I. W., Choi B. W.(2008). A case of empyema and mediastinitis by non-typhi Salmonella. Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases 65537–540. 10.4046/trd.2008.65.6.537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]