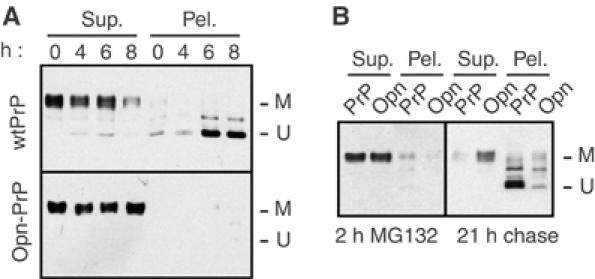

Figure 3.

Effect of prolonged proteasome inhibition on the metabolism of PrP and Opn-PrP. (A) N2a cells transfected with either wild-type PrP (upper panel) or Opn-PrP (lower panel) were treated for between 0 and 8 h with 5 μM MG132 before lysis and fractionation into detergent-soluble (Sup.) and insoluble (Pel.) fractions and analysis by immunoblotting. Note that, with wild-type PrP, an insoluble, unglycosylated species of PrP accumulates over 8 h (U); this is not observed with Opn-PrP, which only shows soluble, mature PrP (M). Results identical to those observed with Opn-PrP were also seen for Prl-PrP (unpublished results; see also Figure 2B). (B) Effect of signal sequence on ‘propagation' of cytoplasmic PrP aggregates. Two parallel plates each of N2a cells transfected with either wild-type PrP or Opn-PrP were treated for 2 h with 5 μM MG132. One plate (left panel) was harvested immediately and analyzed for PrP detergent solubility and aggregation. The second set of dishes was rinsed to remove the MG132, and incubated an additional 21 h in normal media (right panel) before harvesting for analysis of PrP detergent solubility and aggregation. After a 2 h ‘pulse' of MG132, note that the immunoblots of PrP and Opn-PrP are largely indistinguishable: both show nearly quantitative solubility and little unglycosylated, insoluble PrP. After a 21 h chase, wild-type PrP was nearly all unglycosylated and insoluble, as has been proposed to occur by a ‘self-propagation' mechanism (Ma and Lindquist, 2002). Even under these conditions, however, relatively little Opn-PrP was found in the unglycosylated, insoluble form.