Abstract

Background

As a typical geocarpic plant, peanut embryogenesis and pod development are complex processes involving many gene regulatory pathways and controlled by appropriate hormone level. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that play indispensable roles in post-transcriptional gene regulation. Recently, identification and characterization of peanut miRNAs has been described. However, whether miRNAs participate in the regulation of peanut embryogenesis and pod development has yet to be explored.

Results

In this study, small RNA and degradome libraries from peanut early pod of different developmental stages were constructed and sequenced. A total of 70 known and 24 novel miRNA families were discovered. Among them, 16 miRNA families were legume-specific and 12 families were peanut-specific. 30 known and 10 novel miRNA families were differentially expressed during pod development. In addition, 115 target genes were identified for 47 miRNA families by degradome sequencing. Several new targets that might be specific to peanut were found and further validated by RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (RLM 5′-RACE). Furthermore, we performed profiling analysis of intact and total transcripts of several target genes, demonstrating that SPL (miR156/157), NAC (miR164), PPRP (miR167 and miR1088), AP2 (miR172) and GRF (miR396) are actively modulated during early pod development, respectively.

Conclusions

Large numbers of miRNAs and their related target genes were identified through deep sequencing. These findings provided new information on miRNA-mediated regulatory pathways in peanut pod, which will contribute to the comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms that governing peanut embryo and early pod development.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3587-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: High-throughput sequencing, Peanut, miRNA, Hormone, Light, Embryogenesis, Pod development

Background

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is an important crop grown world widely for both oil and protein production. The development of peanut embryo is inhibited by light above ground, and the development of embryo and pod resumes after the elongated ovaries are buried into soil [1–3]. This special developmental process of peanut fruit is a complex, genetically programmed process involving many gene regulatory networks at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Dissecting the molecular mechanism governing peanut embryo and early pod development is helpful to broaden our knowledge on plant embryogenesis. Previous studies demonstrated that peanut embryogenesis and pod development were affected by different wavelengths of light. For example, continuous irradiation with white, red or blue light inhibited embryogenesis and pod development whereas darkness or far red light promoted this process [4–7]. Gynophore elongation responded to light in the opposite manner, which was stimulated when grown in white, red or blue and inhibited when grown in darkness or far red light [6]. Besides, plant endogenous hormones such as auxin (IAA), gibberellic acid (GA), ethylene, abscisic acid (ABA) and brassinolides (BRs) are well known to play critical roles in embryo and fruit development [8, 9]. In peanut, it was reported that either the content or the distribution patterns of hormones significantly changed during peanut early pod development [10–12]. It has been shown that low concentration of IAA promotes peanut pod development, whereas high level inhibits peanut gynophore elongation [13, 14]. GAs can also promote the growth of gynophores in peanut. However, how light regulates hormone biosynthesis and signaling to initiate this interesting biological process is unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs with approximately 20–22 nt in length. MiRNAs regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level in almost all eukaryotes [15]. In general, miRNAs specifically target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) to inhibit their translation or induce their cleavage through partially or fully sequence complementary with their targets [16, 17]. The past decade has witnessed an explosion in our knowledge on miRNA regulation in various biological processes in plants. MiR156 and miR172 coordinately regulate the timing of juvenile-to-adult transition during shoot development [18]. Overexpression of miR167 in wild tomato causes a defect in flower development and female sterility through suppressing Auxin Response Factor 6 (ARF6) and Auxin Response Factor 8 (ARF8) [19]. Both miR156 and miR397 are involved in the regulation of seed development by controlling grain size and shape in rice [20, 21]. Increasing evidence indicated that miRNA and hormone signaling interact to regulate those physiological processes. For examples, GA was shown to modulate miR159 levels during Arabidopsis seed germination [22]. However, our knowledge on miRNA functions controlling the species-specific biological processes in plants is quite limited.

Our previous report has identified miRNAs from peanut root, leaf and stem using deep sequencing approach [23]. However, there is no report on miRNA regulation in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development and no functional miRNA-mRNA modules have been identified from peanut pod. To gain a better understanding of the function of miRNA in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development, the current study characterized the expression profiles of miRNAs in gynophores of three developmental stages during which the repressed embryo and ovary reactivate for further development. Additionally, the degradome library sequencing for global identification of miRNA targets in peanut was performed and new target genes were discovered., many of which involved in plant hormone signal transduction processes. These findings hinted at the important roles of miRNAs in regulating peanut embryogenesis and early pod development and constructed an outline for the interaction between light signal, hormone and miRNAs during peanut embryo and early pod development.

Results

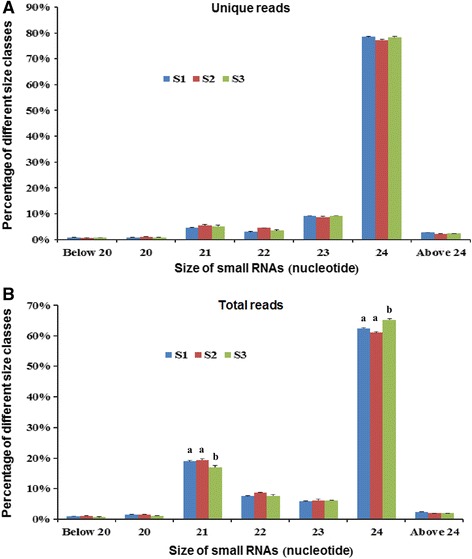

Overview of small RNA profiles in peanut gynophores

To assess the regulatory roles of miRNAs in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development, we profiled sRNA accumulation in S1, S2 and S3 gynophores (Fig. 3a). More than 12 million total reads and 6 million unique reads (stand for read species) were produced from each sample. About 78% of the total reads and 81% of the unique reads were perfectly mapped to peanut genome, and the rates of genomic match were similar across these three stages (Additional file 1: Table S1). The correlation coefficients were more than 0.97 between two biological replicates (Additional file 2: Figure S1). As shown in Fig. 1, 24 nt class of sRNAs showed the highest abundance (~60% of the total and 78% of the unique reads). The secondly abundant class of total reads was 21 nt sRNAs (~19%). This result was consistent with that found in rice [24], tomato [25], soybean [26] and a previous study in peanut [23], but different from that of wheat and grapevine [27, 28]. The proportion of unique reads has no obvious difference among three stages. Interestingly, the proportion of 21 nt total reads decreased slightly and the proportion of 24 nt total reads increased at S3 compared with S1 and S2 (Fig. 1). The size distribution of 20, 22 and 23 nt total reads has no obvious difference among three stages. After removal of rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, repeats sequence and exon sequence (for statistics on read counts, see Additional file 1: Table S1), the remaining unique reads that present in two biological replicates were used to identify miRNAs subsequently.

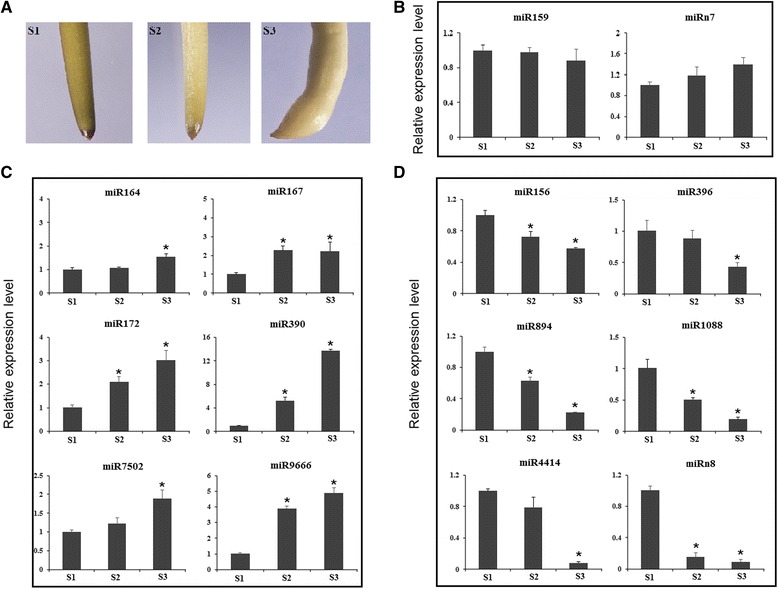

Fig. 3.

Expression analysis of pod development-related miRNAs using qRT-PCR. a Phenotype of gynophore in S1, S2 and S3. b MiRNAs with similar expression level at S1, S2 and S3 gynophores. c Up-regulated miRNAs during pod development. d Down-regulated miRNA during pod development. Error bars indicate SD of three biological replicates. Asterisk indicated a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

Length distribution of small RNA reads in S1, S2 and S3 gynophores. a The distribution of unique small RNAs that present in two biological replicates. b The distribution of total small RNAs that present in two biological replicates

Identification of known and novel miRNAs in peanut gynophore

To identify known miRNAs in peanut, all the unannotated unique reads that perfectly mapped to peanut genome were aligned to plant miRNAs in miRBase (Release 21.0, June 2014). A total of 104 known miRNAs belonging to 70 families were identified (Table 1). Among them, 39 families were known and well conserved that present in two or more plant species. In addition, 19 families were also known but less conserved that present only in one plant species including miR894, miR1088, miR1520, miR2199 and others. Furthermore, 12 peanut-specific miRNA families loaded in miRBase were also detected in our study, for example, miR3508, miR3509, miR3511, and miR3512. After identification of known miRNAs, the remaining unique reads were used to identify novel miRNAs by predicting the hairpin structures of their precursor sequences. 27 novel miRNAs belonging to 24 families were identified in this study and were named as miRn1 to miR24 (Additional file 3: Table S3). The corresponding miRNA* sequences of 15 novel miRNAs were detected, further supporting the existence of these miRNAs. Most novel miRNAs could only be produced from one locus, except miRn10 and miRn23, which were produced from three and four loci, respectively (Additional file 3: Table S3). Stem-loop RT-PCR was performed to validate the predicted new miRNAs and 15 predicted miRNAs were found to be expressed in peanut gynophore (Additional file 4: Figure S2).

Table 1.

Known and novel miRNA families identified in peanut gynorphore

| Well-conserved | Mature sequence | Length(nt) | Star(*) | References | Conserved in other plants |

| miR156 | UGACAGAAGAGAGUGAGCAC | 20 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UUGACAGAAGAGAGUGAGCAC | 21 | Yes | |||

| UGAUAGAAGAGAGUGAGCACA | 21 | Yes | |||

| UUGACAGAAGAGAGUGAGCACA | 22 | Yes | |||

| miR157 | UUGACAGAAGAUAGAGAGCAC | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UGACAGAAGAUAGAGAGCACA | 22 | Yes | |||

| UUGACAGAAGAUAGAGAGCA | 20 | Yes | |||

| miR159 | UUUGGAUUGAAGGGAGCUCUA | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UUUGGAUUGAAGGGAGCUCU | 20 | Yes | |||

| miR160 | UGCCUGGCUCCCUGUAUGCCA | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR162 | UCGAUAAACCUCUGCAUCCAG | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR164 | UGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGUGCA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGUGC | 20 | No | |||

| UGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGUGCAA | 22 | No | |||

| UGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGUGCAAU | 23 | No | |||

| miR165 | UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCCUC | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCC | 19 | Yes | |||

| miR166 | UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCCCC | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UCUCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCC | 21 | Yes | |||

| UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCCC | 20 | Yes | |||

| UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCC | 19 | Yes | |||

| miR167 | UGAAGCUGCCAGCAUGAUCUU | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UGAAGCUGCCAGCAUGAUCU | 20 | Yes | |||

| UGAAGCUGCCAGCAUGAUCUUA | 22 | Yes | |||

| miR168 | UCGCUUGGUGCAGGUCGGGAA | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UCGCUUGGUGCAGGUCGGGA | 20 | Yes | |||

| CGCUUGGUGCAGGUCGGGAAC | 21 | Yes | |||

| miR169a | AAGCCAAGGAUGACUUGCCGG | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR169b | GGCAGGUCAUCUUGUGGCUAU | 21 | Yes | ||

| GGCAGGUCAUCUUGUGGCUAUA | 22 | Yes | |||

| miR171 | GGAUAUUGGUGCGGUUCAAUG | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| UAUUGGUGCGGUUCAAUGAGA | 21 | Yes | |||

| miR172 | AGAAUCUUGAUGAUGCUGCAU | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| AGAAUCUUGAUGAUGCUGCA | 20 | Yes | |||

| miR319 | UUGGACUGAAGGGAGCUCCCU | 21 | Yes | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. | |

| miR390 | AAGCUCAGGAGGGAUAGCGCC | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR391 | UGUCGCAGGAGAAAUAGCACC | 21 | No | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. | |

| miR393 | UCCAAAGGGAUCGCAUUGAUC | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR394 | UUGGCAUUCUGUCCACCUCC | 20 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR396 | UUCCACAGCUUUCUUGAACUU | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| GCUCAAGAAAGCUGUGGGAGA | 21 | Yes | |||

| CUCAAGAAAGCUGUGGGAGA | 20 | Yes | |||

| miR397 | UCAUUGAGUGCAGCGUUGAUG | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR398 | UGUGUUCUCAGGUCACCCCUU | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR399 | GGGCACCUCUUCACUGGCAUG | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. |

| miR403 | UUAGAUUCACGCACAAACUUG | 21 | Yes | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Arabidopsis, Soybean et al. |

| miR408 | CUGGGAACAGGCAGAGCAUGA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Maize et al. |

| miR414 | AACAGAGCAGAACAGAACAGA | 21 | No | Arabidopsis, Rice et al. | |

| miR477 | UCCCUCAAAGGCUUCCAGUA | 20 | No | Physcomitrella patens, Grape et al. | |

| UCCCUCAAAGGCUUCCAGUAU | 21 | No | |||

| miR482a | GGAAUGGGCGGUUUGGGAUGA | 21 | Yes | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. | |

| miR482b | UUCCCAAUUCCACCCAUUCCUA | 22 | Yes | Arabidopsis, Rice, Maize et al. | |

| miR530 | UGCAUUUGCACCUGCACUUUA | 21 | No | Arabidopsis, Soybean, Alfalfa et al. | |

| miR845 | CCAAGCUCUGAUACCAAUUGAUGG | 24 | No | Arabidopsis, Grape et al. | |

| miR1507 | CCUCGUUCCAUACAUCAUCUAA | 22 | Yes | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Alfalfa |

| CCCUCGUUCCAUACAUCAUCUA | 22 | Yes | |||

| miR1509 | UUAAUCAAGGGAAUCACAGUUG | 22 | No | Soybean, Alfalfa | |

| UUAAUCAAGGGAAUCACAGUU | 21 | No | |||

| miR1511 | AACCAGGCUCUGAUACCAUGA | 21 | No | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Alfalfa |

| miR1515 | UCAUUUUUGCAUGCAAUGAUCC | 22 | No | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Alfalfa |

| miR2111 | AUCCUUAGGAUGCAGAUUACG | 21 | No | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Alfalfa |

| miR2118 | UUGCCGAUUCCACCCAUGCCUA | 22 | No | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Soybean, Alfalfa |

| UUGCCGAUUCCACCCAUGCCU | 21 | No | |||

| miR4376 | ACGCAGGAGAGAUGGCGCUAU | 21 | No | Soybean, Tomato et al. | |

| UACGCAGGAGAGAUGGCGCUA | 21 | No | |||

| miR4414 | AGCUGCUGACUCGUCGGUUCA | 21 | Yes | Soybean, Alfalfa | |

| AGCUGCUGACUCGUCGGUUC | 20 | Yes | |||

| miR5225 | UCUGUCGCAGGAGAGAUGACG | 21 | No | Arabidopsis, Soybean, Alfalfa et al. | |

| UCUGUCGCAGGAGAGAUGACGC | 22 | No | |||

| Less-conserved | Mature sequence | Length(nt) | Star(*) | References | Conservative in other plants |

| miR829 | AAGCUCUGAUACCAAUUGAUGGUU | 24 | No | Arabidopsis | |

| miR894 | CGUUUCACGUCGGGUUCACCA | 20 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Physcomitrella patens |

| miR1088 | UGACGGAAGAAAGAGAGCACA | 21 | Yes | Physcomitrella patens | |

| UUGACGGAAGAAAGAGAGCAC | 21 | Yes | |||

| UUGACGGAAGAAAGAGAGCACA | 22 | Yes | |||

| miR1520 | AUGUUGUUAAUUGGAGGAGCGG | 22 | No | Soybean | |

| UGUUGUUAAUUGGAGGAGCGGU | 22 | No | |||

| miR2084 | CGUCAUCGUUGCGAUUGUGGA | 21 | No | Physcomitrella patens | |

| miR2199 | UGAUACACUAGCACGGGUCAC | 21 | No | Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Alfalfa |

| miR2628 | GAAGAAAGAGAAUGAUGAGUAA | 22 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR5021 | UGAGAAGAAGAAGAAGAAGAA | 21 | No | Arabidopsis | |

| miR5221 | AGGAGAGAUGGUGUUUUGACUU | 22 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR5227 | UGAAGAGAAGGGAUUUAUGAA | 21 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR5234 | UGUUAUUGUGGAUGGCAGAAG | 21 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR5244 | UGUCUGAUGAAGAUUGUUGGU | 21 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR5499 | AAGGAAGAAUCAGUUAUGUACA | 22 | No | Rice | |

| miR6300 | GUCGUUGUAGUAUAGUGGUGA | 21 | No | Soybean | |

| miR6475 | UCUUGAGAAGUAGAGAACCGACAG | 24 | No | Populus trichocarpa | |

| miR6478 | CCGACCUUAGCUCAGUUGGUA | 21 | No | Populus trichocarpa | |

| miR7502 | UAACGGUAGAAGAAGGACUGAA | 22 | No | Cotton | |

| miR7696 | UUGAAUUAUGCAGAACUUAUCA | 22 | No | Alfalfa | |

| miR8175 | CGUUCCCCGGCAACGGCGCCA | 21 | No | Arabidopsis | |

| miR9666 | CGGUAGGGCUGUAUGAUGGCGA | 22 | No | Wheat | |

| Peanut-specific | Mature sequence | Length(nt) | Star(*) | References | Conservative in other plants |

| miR3508 | UAGAGGGUCCCCAUGUUCUCA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]; Chi et al., 2011 [35]. | Peanut |

| miR3509 | UGAUAACUGAGAGCCGUUAGAUG | 23 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3511 | GCCAGGGCCAUGAAUGCAGAA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3512 | CGCAAAUGAUGACAAAUAGACA | 22 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3513 | UGAUAAGAUAGAAAUUGUAUA | 21 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3514 | UCACCGUUAAUACAGAAUCCUU | 22 | Yes | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3515 | AAUGUAGAAAAUGAACGGUAU | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3516 | UGCUGGGUGAUAUUGACAGAA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3517 | UCUGACCACUGUGAUCCCGGAA | 22 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3518 | GACCUUUGGGGAUAUUCGUGG | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3519 | UCAAUCAAUGACAGCAUUUCA | 21 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| miR3520 | AGGUGAUGGUGAAUAUCUUAUCUU | 24 | No | Zhao et al., 2010 [24]. | Peanut |

| Novel | Mature sequence | Length(nt) | Star(*) | References | Conservative in other plants |

| miRn1 | UUCCCAAUUCCACCCAUUCCUA | 22 | Yes | ||

| UUUUCCCAAUUCCACCCAUUCC | 22 | Yes | |||

| miRn2 | UUUUCAUUCCAUACAUCAUCUA | 22 | Yes | ||

| UUUUCAUUCCAUACAUCAUCU | 21 | Yes | |||

| UUUCAUUCCAUACAUCAUCUA | 21 | Yes | |||

| miRn3 | UAGAGGGUCCCCAUGUUCUCA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn4 | UGAAGCAAAGUGAUGACUCUG | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn5 | UGUGUGGGUUUCUGGUCUCCAC | 22 | Yes | ||

| miRn6 | AUCCCUCGAAGGCUUCCGCUA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn7 | UUAUUGUCGGACUAAGGUGUCU | 22 | Yes | ||

| miRn8 | UUGAUGCAGUACGGACAAAAG | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn9 | UUUGUGUGAAAGAUCUCCGGA | 21 | No | ||

| miRn10 | CGGUUGUGUGGAGUGCUACGG | 21 | No | ||

| miRn11 | AGGUGCCGGUGCAUUUGCAGG | 21 | No | ||

| miRn12 | AUGAGCUCAGUUGAAGAUUUG | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn13 | GGAACAAAGAGUUUGAGAUGG | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn14 | AAAUUGAUUGAUUAUUCCUGA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn15 | UUGCUAGGAUCGUUUGGCGAU | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn16 | UGCUUAGGAAGGAUUGUCUUA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn17 | AGGGCGUUAUGUAGGGCAUC | 20 | No | ||

| miRn18 | UUGGUAGUAGAAGAAGGAGAU | 21 | No | ||

| miRn19 | UCUGAAUGGGAUGAAAACGCU | 21 | No | ||

| miRn20a | UUUGGAAAUUCGGUACAUUAA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn20b | UUUGGAAACUCGGUACAUUAA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn21 | UUACGUGUACACAAAAAAUCA | 21 | No | ||

| miRn22 | UGAAAGUGGAAUUAAAGCAAG | 21 | No | ||

| miRn23 | GUCGACUUUACAUGAAGUUGA | 21 | Yes | ||

| miRn24 | UUUGGGUCUUGAGAGUACAUG | 21 | No |

* means star sequence of miRNA

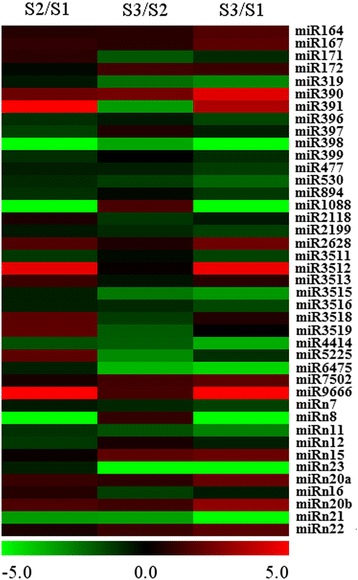

Differential expression of miRNAs during peanut pod development

After normalization, we analyzed the expression pattern of all miRNAs identified in this study (for detailed statistics analysis of all miRNAs, see Additional file 5: Table S2). In total, 40 miRNA families exhibited differential accumulation during early pod development. Of them, 15 known miRNA families and four novel miRNA families were differentially expressed between S1 and S2, whereas 16 known miRNA families and seven novel miRNA families showed different expression between S2 and S3 (Fig. 2). 22 known miRNA families and nine novel miRNA families showed differential accumulation between stages S1 and S3 (Fig. 2). To validate the sequencing data, qRT-PCR was performed to examine the expression of several miRNAs that maybe related to early pod development and the results were in agreement with the sequencing data except for miRn7 where the sequencing result and qRT-PCR showed different patterns (Fig. 3b). As shown in Fig. 3c, miR164, miR167, miR172, miR390, miR7502 and miR9666 were up-regulated significantly, while miR156, miR396, miR894, miR1088, miR4414 and miRn8 were significantly down-regulated during early pod development (Fig. 3d). Different accumulation levels of miRNAs between different developmental stages suggested a possible miRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression during peanut embryo and early pod development in a temporal manner.

Fig. 2.

Clustering and differential expression analysis of miRNAs across S1, S2 and S3 using deep sequencing data. Data was presented as log2fold change by comparing miRNA abundances (TPM) between S2 and S1, S3 and S2, S3 and S1

Degradome sequence analysis and target gene identification

To gain a better understanding of the regulatory role of miRNAs during peanut early pod development, it is necessary to identify their target genes that could provide valuable information for miRNA function during this process. Two degradome libraries from gynophores that unburied and buried in soil for about three days (named as D1 and D2) were constructed separately. By sequencing these two libraries, 17.2 and 23.8 million clean reads were obtained and more than 99% of the sequences were 20 or 21 nt in length. In total, 3,896,267 (53.34%) and 4,600,466 (52.95%) unique reads were mapped to peanut cDNAs which were subjected to target identification (Additional file 6: Table S5). The cleaved transcripts were categorized into three classes (Class 0, 1 and 2), as reported previously [29]. Class 0 transcripts contained only one maximum peak from miRNA-directed cleavage, representing perfect data with no other contamination. Class 1 transcripts contained more than one maximum peaks and the miRNA cleaved peaks are equal to the maximum. Class 2 was transcripts with the peaks from miRNA-directed cleavage lower than the maximum. In this study, a total of 105 target genes for 40 known miRNA families and 10 target genes for seven novel miRNA families were identified (Table 2). Among the 115 identified targets, 79 targets (71%) belonging to class 0, whereas 17 and 19 were classified into class 1 and Class 2, respectively. Most of the cleavage sites were located in CDS region, and only a few cleavage sites were located in 5′-UTR or 3′-UTR (Table 2). The abundance of cleaved transcripts was normalized using ‘reads per 10 million’ (RP10M) method. Interestingly, the cleaved transcripts of many target genes were differently accumulated between these two libraries (Table 2), providing important evidence for miRNA function during early pod development in peanut.

Table 2.

miRNA-mRNA target pairs identified in at least one library of peanut gynorphore with p-value ≤ 0.05

| miRNA | Target gene | Target annotation | Cleavage site(nt) | Target site location | Class | Abundance in D1 (RP10M) | Abundance in D2 (RP10M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ahy-miR156/157 | Araip.QT8AK.1 | Squamosa promoter binding protein | 999 | CDS | 0 | 93 | 54 |

| Araip.0ZF73.1 | Squamosa promoter binding protein | 2069 | 3′-UTR | 0 | 27 | 28 | |

| Araip.II3JP.1 | Squamosa promoter binding protein | 1557 | 3′-UTR | 0 | 628 | 127 | |

| Araip.RD4BX.1 | Squamosa promoter binding protein | 1423 | 3′-UTR | 0 | 64 | 124 | |

| ahy-miR159 | Araip.B1U9G.1 | MYB transcription factor | 661 | CDS | 0 | 7 | 33 |

| Araip.0279H.1 | MYB transcription factor | 1506 | CDS | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| ahy-miR160 | Araip.NYM6Q.1 | Auxin response factor | 1364 | CDS | 0 | 67 | 46 |

| Araip.BYV33.1 | Auxin response factor | 1429 | CDS | 0 | 257 | 430 | |

| Araip.18474.1 | Digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase | 1629 | CDS | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Araip.9V70N.1 | Solute carrier | 955 | CDS | 0 | 15 | 72 | |

| ahy-miR164 | Araip.D25HB.1 | Transcriptional factor NAC | 786 | CDS | 0 | 60 | 130 |

| Araip.DLE10.1 | Heat shock protein | 580 | CDS | 1 | 10 | 12 | |

| ahy-miR166 | Araip.IIT7G.1 | ARF GTPase-activating protein | 1048 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| Araip.P57FD.1 | Serine/threonine kinase | 552 | CDS | 0 | 10 | 40 | |

| Araip.80WHH.1 | Peroxidase | 828 | CDS | 1 | 11 | 5 | |

| Araip.8GH41.1 | Plastidic glucose transporter | 120 | CDS | 0 | 2 | 10 | |

| ahy-miR167 | Araip.7M6VI.1 | Pentatricopeptide repeat protein (PPRP) | 1005 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 118 |

| Araip.R1QSY.1 | Auxin response factor | 568 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR168 | Araip.FPV8R.1 | Argonaute protein 1 | 379 | CDS | 0 | 113 | 188 |

| ahy-miR169 | Araip.T3WCA.1 | Nuclear transcription factor Y | 971 | 3′-UTR | 0 | 45 | 130 |

| ahy-miR171 | Araip.E00UL.1 | Transcription factor GRAS | 542 | CDS | 0 | 209 | 845 |

| Araip.27I5U.1 | Gibberellin receptor | 290 | CDS | 1 | 0 | 5 | |

| ahy-miR172 | Araip.Y07A4.1 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor AP2 | 1253 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 476 | 965 |

| Araip.AE7EH.1 | Cell division protease | 825 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Araip.HRN64.1 | Embryogenesis abundant protein | 55 | 5′-UTR | 1 | 3 | 7 | |

| ahy-miR319 | Araip.SZ7Q5.1 | Monodehydroascorbate reductase | 1263 | CDS | 0 | 88 | 52 |

| Araip.Z17TF.1 | Transcription factor TCP | 1688 | CDS | 0 | 41 | 55 | |

| Araip.KK7TK.1 | DELLA protein | 939 | CDS | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| ahy-miR390 | Araip.VT2PQ.1 | TAS3 | 342 | 0 | 0 | 25 | |

| Araip.43TDN.1 | Solute carrier family 50 (sugar transporter) | 96 | CDS | 0 | 1 | 45 | |

| ahy-miR391 | Araip.5A463.1 | Aluminium induced protein | 309 | CDS | 2 | 6 | 15 |

| Araip.HW8E3.1 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein | 2183 | CDS | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Araip.65E1M.1 | LA RNA-binding protein | 2280 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR393 | Araip.774UX.1 | Auxin signaling F-box protein | 1906 | CDS | 0 | 589 | 968 |

| Araip.0E25I.1 | Auxin signaling F-box protein | 1710 | CDS | 0 | 296 | 429 | |

| Araip.0XA60.1 | Auxin signaling F-box protein | 297 | CDS | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| Araip.NRD2A.1 | Brassinosteroid receptor kinase | 79 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| ahy-miR394 | Araip.Y8EUA.1 | Glutathione S-transferase | 760 | CDS | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| ahy-miR395 | Araip.BC9AA.1 | Cellulose synthase | 1531 | CDS | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| ahy-miR396 | Araip.6YN77.1 | Growth-regulating factor | 922 | CDS | 0 | 422 | 97 |

| Araip.SE9FW.1 | MADS-box transcription factor | 313 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| ahy-miR397 | Araip.QA79V.1 | Laccase 10 (lignin catabolic process) | 743 | CDS | 0 | 8 | 5 |

| Araip.Z5USZ.1 | Laccase 11 (lignin catabolic process) | 746 | CDS | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR398 | Araip.SEZ68.1 | Calcium-dependent protein kinase | 1309 | CDS | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| ahy-miR399 | Araip.G5CUD.1 | Disease resistance protein | 4095 | CDS | 0 | 2 | 24 |

| Araip.RXA31.1 | Expansin-A4(cell wall organization) | 958 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 8 | 4 | |

| Araip.I7ZGU.1 | Unknown protein | 173 | CDS | 0 | 8 | 11 | |

| ahy-miR414 | Araip.IJ273.1 | Ribosome biogenesis protein | 1818 | CDS | 0 | 8 | 20 |

| Araip.467MQ.1 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase | 1586 | CDS | 0 | 10 | 13 | |

| Araip.HJ37G.1 | Phosphoinositide phospholipase C | 1118 | CDS | 0 | 19 | 24 | |

| Araip.Y25R8.1 | ARF guanine-nucleotide exchange factor | 755 | CDS | 0 | 23 | 38 | |

| Araip.98Q8H.1 | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor | 359 | CDS | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| Araip.FPJ1M.1 | DDB1-CUL4 associated factor (protein binding) | 5387 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| ahy-miR477 | Araip.6IZ1V.1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase | 147 | CDS | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Araip.48K15.1 | Heat shock cognate protein | 190 | CDS | 2 | 7 | 7 | |

| Araip.A6M6K.1 | Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase | 163 | CDS | 2 | 30 | 37 | |

| Araip.BP9MY.1 | Myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase | 34 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 0 | 15 | |

| Araip.N0DQ0.1 | Dual specificity protein phosphatase | 33 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Araip.N1PSJ.1 | Glutamate synthase | 22 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Araip.SJE6C.1 | Unknown protein | 64 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| ahy-miR482 | Araip.61H7R.1 | WD repeat-containing protein | 57 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 16 |

| Araip.9T0HK.1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | 1029 | CDS | 0 | 48 | 44 | |

| Araip.313YK.1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | 4548 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Araip.6W5RU.1 | E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | 1890 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Araip.NX28V.1 | Disease resistance protein | 3219 | 3′-UTR | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Araip.BX1V3.1 | Disease resistance protein | 4147 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR530 | Araip.87MXF.1 | Nuclear protein required for cytoskeleton organization | 2092 | CDS | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| Araip.X3V04.1 | Unknown protein | 481 | CDS | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| Araip.YGJ1S.1 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase | 1659 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR1088 | Araip.6BJ8Z.1 | Pentatricopeptide repeat protein (PPRP) | 27 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 113 | 0 |

| ahy-miR1507 | Araip.UGA40.1 | LRR-NB-ARC domain disease resistance protein | 4474 | CDS | 0 | 148 | 119 |

| Araip.SJE6C.1 | DUF4228 domain protein | 64 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 11 | 16 | |

| Araip.4Q4DB.1 | NBS-LRR domain disease resistance protein | 1036 | CDS | 0 | 21 | 0 | |

| Araip.AX6A6.1 | Disease resistance protein | 880 | CDS | 0 | 14 | 0 | |

| Araip.KW5UK.1 | Disease resistance protein | 939 | CDS | 0 | 14 | 0 | |

| Araip.L51CJ.1 | Disease resistance protein | 880 | CDS | 0 | 14 | 0 | |

| ahy-miR1511 | Araip.08W0L.1 | Protein binding protein | 174 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Araip.PD52B.1 | Aluminum sensitive protein | 345 | CDS | 0 | 9 | 10 | |

| ahy-miR1515 | Araip.9C688.1 | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein | 375 | CDS | 1 | 17 | 1 |

| Araip.U8QGY.1 | DNA-lyase-like isoform | 963 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| Araip.5RQ6Z.1 | ATP binding protein | 3153 | CDS | 0 | 32 | 0 | |

| ahy-miR1520 | Araip.AW9H3.1 | DNA methyltransferase | 687 | CDS | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Araip.5K8JY.1 | DNA methyltransferase | 576 | CDS | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Araip.LK5X5.1 | Protein kinase | 2471 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| Araip.U0MS2.1 | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein | 1559 | 3′-UTR | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR2111 | Araip.KV8TN.1 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | 79 | CDS | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Araip.8SC4I.1 | Anaphase-promoting complex subunit | 426 | CDS | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Araip.QW087.1 | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase | 46 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| ahy-miR2118 | Araip.B2Q36.1 | Translation initiation factor eIF | 1643 | CDS | 0 | 38 | 18 |

| Araip.QG6DX.1 | Zinc finger protein | 3535 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Araip.NP9KT.1 | Carboxylate dehydrogenase | 1932 | 3′-UTR | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Araip.E41BL.1 | Disease resistance protein | 344 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 9 | |

| Araip.IKJ6N.1 | Disease resistance protein | 666 | CDS | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| ahy-miR2199 | Araip.I1L37.1 | bHLH transcription factor | 741 | CDS | 0 | 593 | 312 |

| ahy-miR2628 | Araip.LY8H2.1 | Protein kinase | 55 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 24 | 22 |

| ahy-miR3514 | Araip.GQ8VC.1 | Pentatricopeptide repeat protein (PPRP) | 360 | CDS | 0 | 2699 | 435 |

| Araip.N7IGZ.1 | Pentatricopeptide repeat protein (PPRP) | 1134 | CDS | 0 | 53 | 4 | |

| ahy-miR4376 | Araip.0K3S5.1 | Cullin-like protein | 2083 | CDS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Araip.Q4HT6.1 | Methyltransferase | 2372 | CDS | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| Araip.NS167.1 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase-like protein | 2264 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| ahy-miR4414 | Araip.B5L53.1 | DNA binding transcription factor | 989 | CDS | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| ahy-miR5021 | Araip.166TL.1 | MADS-box transcription factor | 189 | 5′-UTR | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| ahy-miR5225 | Araip.WG5D6.1 | Histidine kinase | 180 | CDS | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| ahy-miR6300 | Araip.VJ5LB.1 | Dehydroascorbate reductase | 70 | CDS | 2 | 62 | 198 |

| ahy-miR9666 | Araip.99HRK.1 | Protein kinase (protein ubiquitination process) | 537 | CDS | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| ahy-miRn1 | Araip.9T0HK.1 | E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | 1260 | CDS | 0 | 45 | 43 |

| Araip.71CS3.1 | Transcriptional factor NAC | 1420 | CDS | 0 | 81 | 241 | |

| Araip.QG6DX.1 | Zinc finger protein | 3535 | 3′-UTR | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| ahy-miRn2 | Araip.C0ZFN.1 | LRR-NB-ARC domain disease resistance protein | 704 | CDS | 0 | 17 | 45 |

| Araip.I8IY2.1 | TIR-NBS-LRR domain disease resistance protein | 3782 | CDS | 1 | 17 | 0 | |

| ahy-miRn4 | Araip.JPM97.1 | Receptor kinase | 533 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| ahy-miRn5 | Araip.3TX6Y.1 | Unknown protein | 300 | CDS | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| ahy-miRn7 | Araip.K65JZ.1 | Major intrinsic protein (transporter activity) | 189 | CDS | 0 | 319 | 1084 |

| ahy-miRn10 | Araip.T99DR.1 | DNA polymerases (DNA replication) | 20 | CDS | 1 | 11 | 0 |

| ahy-miRn24 | Araip.NF709.1 | Cytochrome P450 protein | 386 | CDS | 0 | 4 | 9 |

RP10M reads per 10 million clean reads

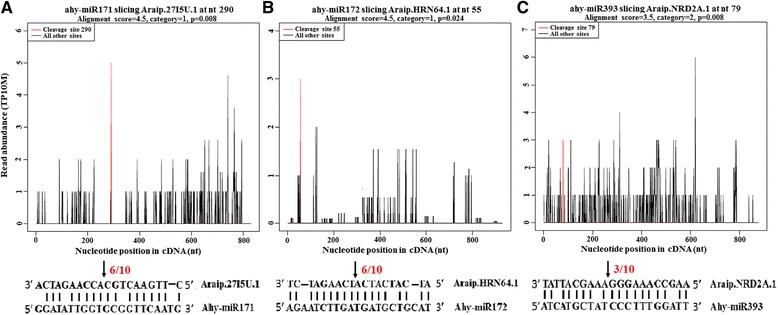

Most targets of the conserved miRNAs were transcription factors such as the squamosa promoter binding-Like (SPL), TEOSINTE BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PRO-LIFERATING CELL FACTOR1 (TCP), MYB, ARF, NAC, GRAS and AP2, which have been identified previously in diverse plant species [30, 31]. MiR399, miR482, miR1507 and miR2118 have been found to target disease resistance protein genes, and miR168 was found to target gene encoding AGO1, a key component of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Additionally, one TAS3 was identified as target of miR390 that give rise to the production of phased ta-siRNAs from that precursor. For the less conserved miRNAs, the targets were not enriched in transcription factors and were more likely to be involved in metabolic and signal transduction. Most peanut-specific miRNAs did not have detectable sliced targets in the degradome libraries. Only two genes encoding pentatricopeptide repeat protein (PPRP) were detected as miR3514 targets. This may be explained by the low abundance of these miRNAs or their sliced targets in peanut gynophore. In addition to the previously identified conserved targets we also identified many new targets in peanut for the known miRNAs. These putative novel targets include digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase and solute carrier (miR160), heat shock protein (miR164), serine/threonine kinase (miR166), PPRP (miR167), DNA methyltransferase (miR1520 and miR4376) and others (Table 2). Interestingly, one embryogenesis abundant protein gene was shown to be target of miR172, one GA receptor gene and one BR receptor kinase gene were shown to be target of miR171 and miR393. These results were independently verified by RLM 5′-RACE analysis (Fig. 4). These conserved miRNAs regulated non-conserved targets in addition to the conserved targets may be specific to peanut and play important roles in pod development. As shown previously in soybean and tomato, the targets of novel miRNAs were not enriched in transcription factors [26, 31]. The present data confirmed these results. Among the 10 targets of novel miRNAs, only one target encoding transcriptional factor (miRn1). Two targets of miRn2 are involved in disease resistance (Table 2). Meanwhile, novel miRNAs targeted a number of functional genes, such as E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase gene (miRn1), major intrinsic protein gene (miRn7), DNA-directed DNA polymerase gene (miRn10) and cytochrome P450 gene (miRn24). However, the function of these newly identified targets, and their regulation by miRNA in peanut pod remains to be determined.

Fig. 4.

Target plots of newly identified target genes for known miRNAs and target validation by RLM 5′-RACE. Peaks in red are the signatures produced by miRNA-directed cleavage. a Cleavage features in gibberellin receptor mRNA by miR171. b Cleavage features in embryogenesis abundant protein mRNA by miR172. c Cleavage features in brassinosteroid receptor kinase mRNA by miR393. RLM 5′-RACE was used to verify the cleavage sites in gibberellin receptor gene, embryogenesis abundant protein gene and brassinosteroid receptor kinase gene by miR171, miR172 and miR393. The numbers above the vertical arrow indicate the number of sequences found at the exact cleavage site

GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses of target genes

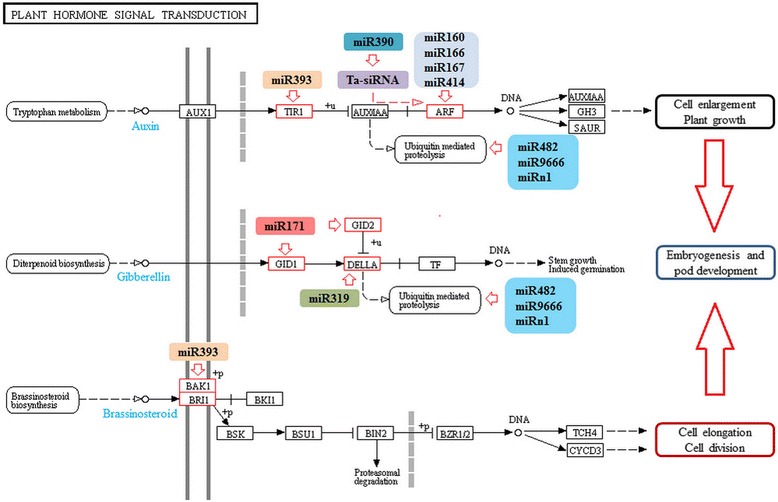

All 115 target genes identified in this study were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) functional classification and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis to perceive their biological roles using WEGO toolkit [32]. A total number of 89 miRNA targets could be annotated by GO classification. It was determined that these target genes were involved in seven types of cellular component, six types of molecular function and 14 types of biological process with the cell part, binding and metabolic process were the most abundant groups in each category (Additional file 7: Figure S3A). According to KEGG analysis, 52 target genes were significantly enriched in 11 pathways including plant hormone signal transduction, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, plant-pathogen interaction, metabolic pathways and ribosome biogenesis (Additional file 7: Figure S3B). Plant hormone signal transduction pathway and the corresponding miRNAs are shown in Fig. 5. In this pathway, 12 genes are targeted by seven miRNAs. In addition, miR390 targets ARF genes indirectly by giving rise to the formation of ta-siRNAs [33]. Moreover, three miRNAs (miR482, miR9666 and miRn1) are involved in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis process by targeting E3 ubiquitin ligase gene, through which control the protein accumulation levels of AUX and DELLA in IAA and GA pathways, respectively. These findings highlight the significant regulation of miRNAs on peanut early pod development by effecting hormone signaling transduction pathways.

Fig. 5.

KEGG pathways related to plant hormone signal transduction targeted by peanut miRNAs

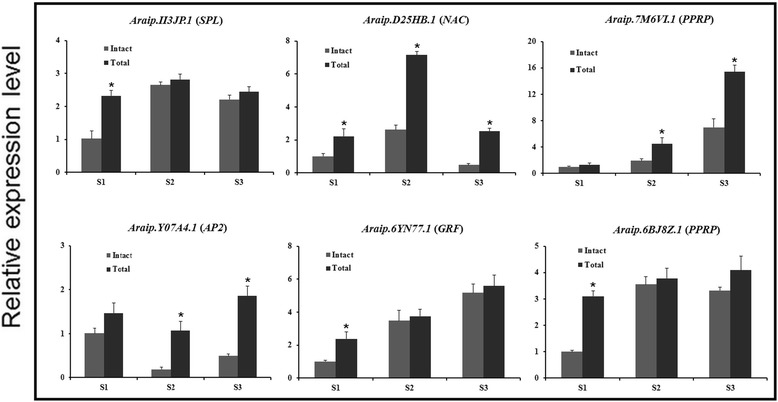

Correlated analysis between miRNAs and target mRNAs during early pod development

Integrated analysis of miRNAs and their targets expression can help to understand the regulatory pathways of miRNAs and identify functional miRNA-mRNA modules involved in peanut embryo and early pod development. Here, we profiled the accumulation of six target mRNAs validated by degradome sequencing in peanut gynophore using qRT-PCR. To determine exactly how much of the mRNA were cleaved by miRNA, we detected the total mRNA and the intact mRNA that uncleaved by miRNA using two pairs of primers designed in the 3′-UTR region and spanning the miRNA target site, respectively [31]. As shown in Fig. 6, the total mRNA of all the target genes increased during early pod development and the intact mRNA were also increased except for AP2 which is targeted by miR172. Meanwhile, increased cleavage of the NAC, PPRP and AP2 transcripts (targeted by miR164, miR167 and miR172, respectively) and decreased cleavage of the GRF and another PPRP transcripts (targeted by miR396 and miR1088, respectively) were observed at S2 and S3 compared with S1 stage, which in agreement with the miRNA expression profiling that miR164, miR167 and miR172 were up-regulated while miR396 and miR1088 were decreased during peanut early pod development. These results suggested that miRNA significantly modulate their intact target mRNAs accumulation at the post-transcriptional level to regulate them at appropriate expression levels, controlling peanut early pod development.

Fig. 6.

qRT-PCR analysis of total and intact mRNA levels in peanut gynophore using two different primers sets. Error bars indicate the SD of three biological replicates. The asterisk indicated a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05)

Discussion

Roles of miRNAs during peanut embryogenesis and early pod development

The early stage of peanut pod development including gynophore elongation, pod enlargement, cell differentiation and embryogenesis is a complicated biological process regulated by coordinated gene expression. Increasing evidence indicated that miRNAs play important regulatory roles in cell differentiation and plant development. However, the function of miRNAs during peanut embryogenesis and early pod development has not been addressed. In previous reports, Zhao and Chi identified 22 and 33 known miRNA families from libraries constructed using mixed RNAs from peanut root, stem, leave and seed, respectively [23, 34]. In the current study, deep sequencing of small RNA libraries constructed using peanut S1, S2 and S3 gynophore RNAs led to the discovery of 69 known miRNA families and 24 novel miRNA families. Interestingly, 34 known miRNA families were first identified in peanut, suggesting that they were preferentially expressed and specific to peanut gynophore or young pod. Among them, 10 known but less conserved miRNAs(miR1520, miR2199, miR2628, miR4414, miR5221, miR5227, miR5234, miR5244, miR6300 and miR7696) were only identified in leguminous plants [35, 36]. In addition, 12 known but non-conserved miRNAs were also detected in peanut gynophore with a lower abundance than that of conserved miRNAs. It has been proposed that conserved miRNAs are probably responsible for regulation of the basic cellular and developmental processes, while the species-specific miRNAs are involved in the regulation of species-specific regulatory pathways [37, 38]. These legume- or peanut-specific miRNAs may function in regulation of gene expression during peanut- or pod-specific processes. Interestingly, miRn8 accumulated only in S1 stage and peanut-specific miR3512 expressed only in S2 and S3 stages, indicating that they act in a tissue- or cell- specific manner and may play essential roles in peanut embryo and early pod formation.

Putative mRNA-miRNA modules involved in peanut early pod development

To further explore the regulatory roles of miRNAs during peanut embryogenesis and early pod development, we profiled their differential expression among three developmental stages. Based on the normalized abundance of high-throughput sequencing data, 40 miRNA families were differentially accumulated during early pod development which may contribute to cell proliferation and differentiation during embryogenesis and early developmental stage of peanut pod. A large number of conserved target genes for differentially expressed miRNAs were identified, such as SPL, MYB, ARF, NAC, NF-Y, GRAS, AP2 and TCP type transcription factors, which have been experimentally validated by previous studies [30, 31]. Based on the normalized abundance of degradome sequencing data, miR156-mediated cleavage of SPL (Araip.II3JP.1), miR164-mediated cleavage of NAC (Araip.D25HB.1), miR167-mediated cleavage of PPRP (Araip.7M6VI.1), miR171-mediated cleavage of GRSA (Araip.E00UL.1), miR172-mediated cleavage of AP2 (Araip.Y07A4.1), miR393-mediated cleavage of F-box gene (Araip.774UX.1), miR396-mediated cleavage of GRF (Araip.6YN77.1) and miR1088-mediated cleavage of another PPRP (Araip.6BJ8Z.1) were the most abundant and differently accumulated between the two degradome libraries. These miRNA-mRNA modules might be involved in regulating biological processes that facilitate peanut embryogenesis and pod development. Indeed, miR156-mediated regulation of SPL transcripts has been proved to play critical roles in regulating zygotic embryo development in Arabidopsis [39]. MiR164-mediated suppression of NAC is required for embryogenesis, shoot meristem development, lateral root formation, senescence and other developmental processes [40]. Our results showed that miR156-directed cleavage of SPL declined whereas miR164-directed cleavage of NAC transcripts increased during early pod development (Fig. 6), which consists with the earlier observed expression profiles of miR156 and miR164 determined by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3). Moreover, a large number of new targets were also detected for conserved as well as non-conserved miRNAs, although splicing frequency of these new targets was very low. For example, one embryogenesis abundant protein gene emerged as the target of miR172. Three miRNAs (miR167, miR1088 and miR3514) target genes encoding PPRP. PPRP has been demonstrated to play important roles in the first mitotic division during gametogenesis and in cell proliferation during embryogenesis [41]. These results suggested the present of non-conserved miRNA-mRNA modules that were specific to peanut and play crucial roles in regulating peanut-specific biological processes that promote embryo and early pod development.

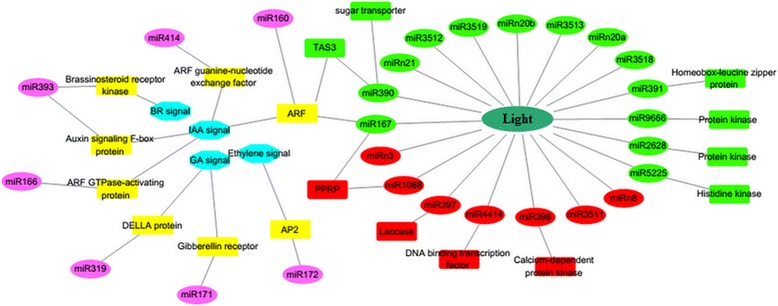

Network consist of hormone, light signal and miRNAs in regulating peanut embryo and early pod development

Peanut is a typical ‘aerial flower and subterranean fruit’ plant, and peanut fruit completes the development process under ground. After fertilization, peanut zygote divides few times and then the embryonic development stops when exposed to light condition or normal day/night period. Along with the elongation of gynophore, the tip region (containing the embryo) of gynophore is buried into soil, peanut embryogenesis and pod development resumes in the darkness, indicating that light is an important environmental signal that regulates pod formation and development. Physiological studies demonstrated that red light and white light inhibited the growth of peanut ovules [6, 42]. Besides, multiple hormonal pathways are often modulated by light signal to control diverse developmental processes. Given that the critical roles of miRNA on plant embryogenesis, dissect the crosstalk among light signal, endogenous hormones and miRNAs would be of great interest. Our results showed that the expression of many known and novel miRNAs that involved in embryo development was affected by light signal through profiling analysis between S1 (light condition) and S2 (dark condition) such as miR167, miR390 and miR1088 (Fig. 7). MiR167 and miR1088 mediated PPRP cleavage as well as miR390 mediated ARF cleavage were known to participate in embryogenesis [41, 43]. This result suggests that miRNA might be a molecular integrator that link light signaling to the multiple hormone pathways such as auxin.

Fig. 7.

Regulatory network consist of light, miRNAs and hormone during peanut embryo and early pod development. In green ovals are up-regulated miRNAs and in red ovals are down-regulated miRNAs under dark condition

Plant endogenous hormones play vital roles in diverse developmental processes. For instance, GA can regulate gene expression to control stem elongation, seed germination and embryo development in plants [44–46]. Auxin is considered to be the main hormone involved in plant differentiation through controlling cell polarity, cell division and cell elongation [43, 47]. Furthermore, miRNA regulation of auxin pathway plays an important role during cotton somatic embryogenesis [48]. In peanut gynophore, either the content or the distribution patterns of IAA, GA and BR significantly changed from S1 to S3, suggesting that these hormones are key regulators of peanut embryo development and pod formation [12, 49]. Here, it was found that eight target genes that participate in auxin signal transduction, two genes that participate in GA signal transduction and one gene that participates in BR signal transduction were identified as miRNA targets through degradome sequencing analysis (Fig. 5). In addition, we also found that miR390 could mediate the cleavage of TAS3 in peanut. The cleavage of TAS3 by miR390 could induce the formation of phased ta-siRNAs that mediate the regulation of auxin signal and in turn influence diverse developmental processes in flowering plants [33, 50]. Profiling analysis showed that several miRNAs (miR167, miR319 and miR390) participating in auxin and GA signal transduction pathways were differentially accumulated during peanut pod development. These differentially expressed miRNAs and their hormone-related targets might be essential components of the regulatory networks in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development (Fig. 7). Collectively, miRNAs, hormones and light signal comprises a complex network regulating specific biological processes controlling peanut embryo and pod development.

Conclusions

High-throughput sequencing together with bioinformatics and experimental approaches were used to explore the function of miRNAs in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development. A total of 70 known and 24 novel miRNA families were discovered. Among them, many miRNAs were legume-specific or peanut-specific and differentially expressed during early pod development. In addition, 115 target genes were identified for 47 miRNA families. Several new targets that might be specific to peanut were found and further validated by RLM 5′-RACE. These peanut-specific and differentially expressed miRNAs and their corresponding target genes might be essential components of the regulatory networks controlling in peanut embryogenesis and early pod development.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Plant materials were collected from cultivated peanut (Luhua-14) grown in the experimental farm of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences with normal day/night period. The gynophores were staged based on developmental stage and visual morphology. The above ground downward growing gynophores (with green or purple color, 5–10 cm in length) were assigned as stage 1 (S1). The stage 2 (S2) gynophores were those that buried in the soil for about three days with thicker diameter than S1 gynophores. S2 gynophores were white in color, the enlargement of the ovary region was not observed. Stage 3 (S3) gynophores were those that buried in soil for about nine days. The ovary regions of S3 gynophores were obviously enlarged. About 5 mm tip region of gynophore was manually dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for the following experiments. Two biological replicates were prepared for each stage. These samples were referred as S1-R1 and S1-R2, S2-R1 and S2-R2, S3-R1 and S3-R2 throughout the manuscript.

Small RNA and degradome library construction and sequencing

Total RNAs were extracted from peanut gynophores using CTAB reagent. For small RNA library construction, 18 to 30 nt small RNAs were fractionated through polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and ligated with 5′ and 3′ RNA adapter by T4 RNA ligase. Reverse transcription reaction and a short PCR were performed to obtain sufficient cDNA for sequencing. To identify the potential targets, two degradome libraries were constructed from aerial grown gynophores (named as D1) and gynophores that buried into soil (named as D2) separately. In brief, poly(A) RNAs that possess a 5′-phosphate were extracted and ligated to a RNA adaptor containing a 3′ MmeI recognition site by T4 RNA ligase. Reverse transcription reaction and a short PCR were performed to obtain double stranded DNA. The DNA product was purified and digested with MmeI. Then a double stranded DNA adaptor was ligated to the double-stranded DNA. The ligated products were amplified by PCR and gel-purified for sequencing. All small RNA and degradome libraries were submitted to BGI (Shenzhen, China) for 49-bp single-end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2000. The raw sequence data of small RNA library and degradome library were available at NCBI Short Read Archive (SRX2374091 and SRX1734291).

Bioinformatics analysis of small RNA sequencing data

The raw reads were preprocessed with Fastx-toolkit pipeline (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) to trim the adapter sequences and filter out low-quality sequences and repetitive reads. Reads larger than 30 nt and smaller than 18 nt were discarded. Then the clean reads were aligned to peanut reference genome (https://peanutbase.org/) using SOAP2 [51]. Only perfectly matched reads were obtained and used for subsequent analysis. Reads matched to rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA and protein-coding genes were excluded. To identify conserved miRNAs, we aligned all reads against known miRNA registered in miRBase (Release 21.0, April 2014) allowing no mismatch. For novel miRNA identification, their corresponding precursor sequences were checked using mireap (https://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap/) to ensure the miRNA precursors have their expected secondary structures. The expression of miRNAs during peanut pod development was analyzed by reads per million (RPM). The differential expression of miRNAs was performed using DESeq package (version 2.14, http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq.html) with a criterion of |log2fold change| ≥ 1 and adjusted p-values < 0.05 [52].

Bioinformatics analysis of degradome sequencing data

Clean reads were obtained using Fastx-toolkit pipeline (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) to remove adaptor sequences and low quality reads. Only 20 and 21 nt reads that perfectly matched to peanut cDNA sequences were collected and extend to 35–36 nt by adding 15 nt of upstream sequence for potentially cleaved targets identification. The CleaveLand pipeline v3.0.1 was used to align the 35–36 nt sequence to peanut miRNAs [53]. All alignments with scores up to 5 and no mismatches at the cleavage site (between the 10th and 11th nucleotides of the miRNAs) were considered candidate targets. Tag numbers for target genes were normalized by RP10M (reads per 10 million).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The stem-loop quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to analyze the expression of miRNAs as described previously [54]. Reverse transcription reactions were performed at 16 °C for 30 min, followed by 60 cycles at 30 °C for 30 s, 42 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 1 s and terminated by incubating at 85 °C for 5 min. U6 was used as the internal control. For target genes, 2 μg DNase I-treated total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using olig(dT)18 primer, and peanut actin gene was used as the internal control. Reverse transcription was performed at 42 °C for 60 min and 85 °C for 5 min. SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad) was used in all qRT-PCR reactions with an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 5 s and 72 °C for 8 s. Three biological replicates were prepared for each sample. The relative expression changes of miRNAs were calculated using the 2-△△Ct method. Student’s t-test was used to access whether the qRT-PCR results were statistically different between two samples (*P < 0.05). Primers used in all qRT-PCR experiments were listed in Additional file 8: Table S4.

RLM-5′ RACE

Total RNA (200 μg) from peanut gynophore was extracted using CTAB reagent and mRNA was purified using the Oligotex kit (Qiagen). RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (RLM-5′ RACE) was performed with the RLM-RACE kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech). The final PCR product was extracted and purified from 2% agarose gel, cloned into pMD18-T simple vector (Takara). Plasmid DNA from 10 different colonies was sequenced. Gene specific primers used for RLM-5′ RACE experiments were listed in Additional file 8: Table S4.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31471526 and 31500217), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M570605), Fund of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2014CGPY10) and Young Talents Training Program of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data of small RNA library and degradome library were available at NCBI Short Read Archive (SRX2374091 and SRX1734291).

Authors’ contributions

XW conceived and designed the research. CG and PW prepared the samples, performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the original manuscript. ZJ finalized the figures and tables. SZ and CL managed the plant materials. HX, CZ, LH, and YZ performed some experiments and took care of the plants. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 3′-UTR

3′-Untranslated Region

- 5′-UTR

5′-Untranslated Region

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- AGO1

Argonaute1

- AP2

Apetala2

- ARF

Auxin response factor

- BRs

Brassinolides

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- CDS

Code Sequence

- GA

Gibberellic acid

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GRF

Growth regulating factor

- IAA

Indole-3-acetic acid

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- miRNAs

microRNA

- mRNAs

Messenger RNAs

- NAC

NAM/ATAF/CUC2

- NF-Y

Nuclear transcription factor Y

- nt

Nucleotide

- PPRP

Pentatricopeptide repeat protein

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Real-time PCR

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RLM 5′-RACE

RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends

- RP10M

Reads per 10 million clean reads

- RPM

Reads per million clean reads

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNA

- snoRNA

Small nucleolar RNA

- snRNA

Small nuclear RNA

- SPL

Squamosa promoter binding like

- ta-siRNAs

Trans-acting siRNAs

- TCP

TEOSINTE BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PRO-LIFERATING CELL FACTOR1

- tRNA

Transfer RNA

Additional files

Statistics of different small RNAs from small RNA libraries. (DOCX 20 kb)

The correlation coefficient of miRNA expression between two biological replicates of S1, S2 and S3. (TIF 7318 kb)

Detailed information of novel miRNAs in peanut. (XLS 46 kb)

Validation of novel miRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. No template: no RNA was added as a negative control. (TIF 3171 kb)

The miRNA normalization, fold change and statistical significance of known or novel miRNAs in S1, S2, S3 gynophores. (XLSX 61 kb)

Statistics of different small RNAs categories by degradome sequencing. (DOCX 17 kb)

Summary of GO classification of miRNA targets in peanut gynophore. (TIF 1258 kb)

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for qRT-PCR. (XLS 31 kb)

Contributor Information

Chao Gao, Email: gsuperman114@163.com.

Pengfei Wang, Email: fengqiaoyouzi@126.com.

Shuzhen Zhao, Email: zhaoshuzhen51@126.com.

Chuanzhi Zhao, Email: 15966671002@126.com.

Han Xia, Email: coldxia@126.com.

Lei Hou, Email: houlei9042@qq.com.

Zheng Ju, Email: juzhengcau@163.com.

Ye Zhang, Email: 489284555@qq.com.

Changsheng Li, Email: 1067207956@qq.com.

Xingjun Wang, Phone: +86 531 83179042, Email: xingjunw@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Smith B. Arachis hypogaea. aerial flower and subterranean fruit. Am J Bot. 1950;37(10):802–15. doi: 10.2307/2437758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stalker H, Wynne J. Photoperiodic response of peanut species 1. Peanut Sci. 1983;10(2):59–62. doi: 10.3146/i0095-3679-10-2-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamski E, Ziv M. Pod formation and its geotropic orientation in the peanut, Arachis hypogaea L., in relation to light and mechanical stimulus. Ann Bot. 1975;40:631–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a085173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziv M. Photomorphogenesis of gynophore, pod and embryo in peanut, Arachis hypogaea L. Ann Bot. 1981;48:353–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziv M, Sager J. The influence of light quality on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) gynophore pod and embryo development in vitro. Plant Sci Lett. 1984;34:211–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4211(84)90144-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson L, Ziv M, Deitzer G. Photocontrol of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) embryo and ovule development in vitro. Plant Physiol. 1985;78(2):370–3. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.2.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalamovitz N, Ziv M, Zamski E. Light, dark and growth regulators involvement in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) pod development. Plant Growth Regul. 1995;16:37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00040505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrani J, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fos M, Garcia-Martinez J. Auxin-induced fruit-set in tomato is mediated in part by gibberellins. Plant J. 2008;56:922–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnaud N, Girin T, Sorefan K, Fuentes S, Wood T, Lawrenson T, Sablowski R, Ostergaard L. Gibberellins control fruit patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2127–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.593410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziv M, Zamski E. Geotropic responses and pod development in gynophore explants of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultured in vitro. Ann Bot. 1975;39(3):579–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a084968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moctezuma E. Changes in auxin patterns in developing gynophores of the peanut plant (Arachis hypogaea L.) Ann Bot. 1999;83(3):235–42. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1998.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu W, Chen X, Li H, Zhu F, Hong Y, Varshney R, Liang X. Comparative transcriptome analysis of aerial and subterranean pods development provides insights into seed abortion in peanut. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85(4–5):395–409. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0193-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moctezuma E, Feldman L. Growth rates and auxin effects in graviresponding gynophores of the peanut, Arachis hypogaea (Fabaceae) Am J Bot. 1998;85(10):1369–76. doi: 10.2307/2446395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moctezuma E. The peanut gynophore: a developmental and physiological perspective. Can J Bot. 2003;81(3):183–90. doi: 10.1139/b03-024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinhart B, Weinstein E, Rhoades M, Bartel B, Bartel D. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1616–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartel D. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones-Rhoades M, Bartel D, Bartel B. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Park M, Conway S, Wang J, Weigel D, Poethig R. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;138:750–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu N, Wu S, Van Houten J, Wang Y, Ding B, Fei Z, Clarke T, Reed J, van der Knaap E. Down-regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS 6 and 8 by microRNA 167 leads to floral development defects and female sterility in tomato. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2507–20. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, Wu K, Yuan Q, Liu X, Liu Z, Lin X, Zeng R, Zhu H, Dong G, Qian Q, Zhang G, Fu X. Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat Genet. 2012;44:950–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang YC, Yu Y, Wang CY, Li ZY, Liu Q, Xu J, Liao JY, Wang XJ, Qu LH, Chen F, Xin PY, Yan CY, Chu JF, Li HQ, Chen YQ. Overexpression of microRNA OsmiR397 improves rice yield by increasing grain size and promoting panicle branching. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:848–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reyes J, Chua N. ABA induction of miR159 controls transcript levels of two MYB factors during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2007;49:592–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao C, Xia H, Frazier T, Yao Y, Bi Y, Li A, Li M, Li C, Zhang B, Wang X. Deep sequencing identifies novel and conserved microRNAs in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morin R, Aksay G, Dolgosheina E, Ebhardt H, Magrini V, Mardis E, Sahinalp S, Unrau P. Comparative analysis of the small RNA transcriptomes of Pinus contorta and Oryza sativa. Genome Res. 2008;18:571–84. doi: 10.1101/gr.6897308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao C, Ju Z, Cao D, Zhai B, Qin G, Zhu H, Fu D, Luo Y, Zhu B. MicroRNA profiling analysis throughout tomato fruit development and ripening reveals potential regulatory role of RIN on microRNAs accumulation. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;13:370–82. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song Q, Liu Y, Hu X, Zhang W, Ma B, Chen S, Zhang J. Identification of miRNA and their target genes in developing soybean seeds by deep sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao Y, Guo G, Ni Z, Sunkar R, Du J, Zhu J, Sun Q. Cloning and characterization of microRNAs from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genome Biol. 2007;8:96–108. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pantaleo V, Szittya G, Moxon S, Miozzi L, Moulton V, Dalmay T, Burgyan J. Identification of grapevine microRNAs and their targets using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Plant J. 2010;62:960–76. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2010.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addo-Quaye C, Eshoo T, Bartel D, Axtell M. Endogenous siRNA and miRNA targets identified by sequencing of the Arabidopsis degradome. Curr Biol. 2008;18:758–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Zheng Y, Addo-Quaye C, Zhang L, Saini A, Jagadeeswaran G, Axtell M, Zhang W, Sunkar R. Transcriptome-wide identification of microRNA targets in rice. Plant J. 2010;62:742–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlova R, van Haarst J, Maliepaard C, van de Geest H, Bovy A, Lammers M, Angenent G, de Maagd R. Identification of microRNA targets in tomato fruit development using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:1863–78. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye J, Fang L, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Chen J, Zhang Z, Wang J, Li S, Li R, Bolund L, Wang J. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:293–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fahlgren N, Montgomery T, Howell M, Allen E, Dvorak S, Alexander A, Carrington J. Regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:939–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chi X, Yang Q, Chen X, Wang J, Pan L, Chen M, Yang Z, He Y, Liang X, Yu S. Identification and characterization of microRNAs from peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lelandais-Brière C, Naya L, Sallet E, Calenge F, Frugier F, Hartmann C, Gouzy J, Crespi M. Genome-Wide Medicago truncatula small RNA analysis revealed novel MicroRNAs and isoforms differentially regulated in roots and nodules. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2780–96. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joshi T, Yan Z, Libault M, Jeong D, Park S, Green P, Sherrier D, Farmer A, May G, Meyers B, Xu D, Stacey G. Prediction of novel miRNAs and associated target genes in Glycine max. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glazov E, Cottee P, Barris W, Moore R, Dalrymple B, Tizard M. A microRNA catalog of the developing chicken embryo identified by a deep sequencing approach. Genome Res. 2008;18:957–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.074740.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li T, Chen J, Qiu S, Zhang Y, Wang P, Yang L, Lu Y, Shi J. Deep sequencing and microarray hybridization identify conserved and species-specific microRNAs during somatic embryogenesis in hybrid yellow poplar. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nodine M, Bartel D. MicroRNAs prevent precocious gene expression and enable pattern formation during plante mbryogenesis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2678–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.1986710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan K, Wang M, Miao Y, Ni M, Bibi N, Yuan S, Li F, Wang X. Molecular evolution and expansion analysis of the NAC transcription factor in zea mays. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu Y, Li C, Wang H, Chen H, Berg H, Xia Y. AtPPR2, an Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat protein, binds to plastid 23S rRNA and plays an important role in the first mitotic division during gametogenesis and in cell proliferation during embryogenesis. Plant J. 2011;67:13–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zharare G, Blamey F, Asher C. Initiation and Morphogenesis of Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Pods in Solution Culture. Ann Bot. 1998;81:391–6. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1997.0569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauer M, Robert S, Kleine-Vehn J. Auxin: simply complicated. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:2565–77. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gocal G, Sheldon C, Gubler F, Moritz T, Bagnall D, MacMillan C, Li S, Parish R, Dennis E, Weigel D, King R. GAMYB-like genes, flowering, and gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1682–93. doi: 10.1104/pp.010442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Achard P, Herr A, Baulcombe D, Harberd N. Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development. 2004;131:3357–65. doi: 10.1242/dev.01206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White C, Rivin C. Gibberellins and seed development in maize. II. Gibberellin synthesis inhibition enhances abscisic acid signaling in cultured embryos. Plant Physiol. 2007;122:1089–98. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schruff M, Spielman M, Tiwari S, Adams S, Fenby N, Scott R. The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 gene of Arabidopsis links auxin signalling, cell division, and the size of seeds and other organs. Development. 2006;133:251–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang X, Wang L, Yuan D, Lindsey K, Zhang X. Small RNA and degradome sequencing reveal complex miRNA regulation during cotton somatic embryogenesis. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:1521–36. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia H, Zhao C, Hou L, Li A, Zhao S, Bi Y, An J, Zhao Y, Wan S, Wang J. Transcriptome profiling of peanut gynophores revealed global reprogramming of gene expression during early pod development in darkness. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):517. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia D, Collier SA, Byrne ME, Martienssen RA. Specification of leaf polarity in Arabidopsis via the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:933–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li R, Yu C, Li Y, Lam T, Yiu S, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Addo-Quaye C, Miller W, Axtell M. CleaveLand: a pipeline for using degradome data to find cleaved small RNA targets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:130–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varkonyi-Gasic E, Wu R, Wood M, Walton E, Hellens R. Protocol: a highly sensitive RT-PCR method for detection and quantification of microRNAs. Plant Methods. 2007;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of small RNA library and degradome library were available at NCBI Short Read Archive (SRX2374091 and SRX1734291).