Abstract

Background

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of a high-intensity model (HIM) and a low-intensity model (LIM) of behaviour change communication interventions in Bihar and Jharkhand states of India designed to improve women's knowledge and usage of safe abortion services, as well as the dose effect of intervention exposure.

Methods

We conducted two cross-sectional household surveys among married women aged 15–49 years in intervention and comparison districts. Difference-in-difference models were used to assess the efficacy of the intervention, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

Although both intervention types improved abortion knowledge, the HIM intervention was more effective in improving comprehensive knowledge about abortion. In particular, there were improvements in knowledge on legality of abortion (AOR=2.2; 95% CI 1.6 to 2.9) and nearby sources of safe abortion care (AOR=1.7; 95% CI 1.2 to 1.3).

Conclusions

Higher level of exposure to abortion-related messages was related to more accurate knowledge about abortion within both intervention groups. Evidence was mixed on changes in abortion care-seeking behaviour. More work is needed to ensure that women seek safe abortion services in lieu of informal services that may be more likely to lead to postabortion complications.

Keywords: abortion, behaviour change, India, knowledge, post abortion

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The intervention was successful in improving knowledge about the legal aspects of abortion and where to access safe abortion services.

The study also found evidence of a dose–response relationship between level of exposure to abortion-related messages and accurate knowledge about abortion (higher dose=more accurate knowledge).

The findings cannot be generalised to the whole of Bihar and Jharkhand.

Owing to the small number of women who reported abortions within the past 3 years, we were unable to compare changes in use of abortion services in the intervention and comparison districts with confidence.

Introduction

India's Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act (MTP Act) of 1971 permits a woman to seek abortion services from a registered medical practitioner at any approved facility for a range of indications, including to save her life, preserve her physical and mental health, for economic or social reasons, in cases of rape or incest, fetal impairment or when pregnancy results from contraceptive failure (for married women). Today, unsafe abortion is still a significant public health problem in India, with complications of abortion accounting for 8–9% of maternal deaths.1 Every year an estimated 6.4 million abortions are performed in India, and over half (56%) are estimated to be unsafe.2 Many women are not aware that abortion is legal, nor are they aware of facilities that are certified by the government to provide abortion services.3 4

Behaviour change communication (BCC) interventions show promise in improving knowledge of contraceptive use, immunisation and HIV/AIDS.5 6 BCC programmes include a wide range of interventions that fall into three broad categories: mass media, interpersonal communication (IPC) and community mobilisation. These three types of communication can improve indicators commonly used by public health programme implementers, including knowledge, attitudes, intentions and behaviours.7 However, these lines of BCC interventions for large populations are often expensive and complex8 and are only appropriate with sustainable resource support.9 Although there is some literature showing that BCC interventions can improve knowledge and perceptions of abortion law and services, evidence is still limited on the relative efficacy of cost-intensive and low-cost communication interventions for abortion.10

Ipas Development Foundation (IDF) in coordination with the state governments of Bihar and Jharkhand piloted two models of BCC interventions in two selected districts each in Bihar and Jharkhand,11 a high-intensity model (HIM) and a low-intensity model (LIM) both described further below. This study examines the relative effectiveness of the HIM and LIM models in terms of improving women's knowledge and awareness of the legal aspects and sources of safe abortion services and experiences with regard to usage of abortion services; the study also examines the association between exposure to the intervention and levels of abortion knowledge.

Methods

Study setting

In coordination with the state governments, four intervention districts where IDF strengthened the institutional capacity of the districts to train medical doctors on comprehensive abortion care (CAC) services were purposively selected for the BCC interventions. Overall, six districts were selected for this study for equal representation from Bihar and Jharkhand: two HIM districts, two LIM districts and two comparison districts. The HIM intervention was implemented in Patna district in Bihar and Lohardaga district in Jharkhand, and the LIM intervention was implemented in Kishanganj district in Bihar and Dhanbad district in Jharkhand. The two comparison districts, Saran in Bihar and Gumla in Jharkhand, were selected because they had sociodemographic characteristics similar to the intervention districts.12 The number of approved MTP sites varied across the selected districts from only five approved MTP sites in Gumla and Lohardaga districts to 20 approved MTP sites in Patna district in 2011.13 14 After pooling across the two states, the numbers were similar in each group with 25 approved MTP sites in HIM districts, 22 approved MTP sites in LIM districts and 12 approved MTP sites in comparison districts.

Intervention description

The communication campaign was centred on a fictional young woman called Kalyani, meaning auspicious. Using Kalyani as the protagonist, two different BCC models were introduced to increase awareness and service usage among women in HIM and LIM districts. The HIM intervention consisted of communication activities including interpersonal communication through group meetings and interactive games, wall signs, street dramas and distribution of low-literacy reference materials. IPC group meetings were carried out in different locations of the village with 8–10 married women aged 15–49 years. At the end of each group meeting, participants played interactive games to reinforce the key messages delivered in the meeting. Wall paintings and posters included the legality, availability, modern techniques of abortion and safety of first trimester abortion and were placed in central locations of the village and health facilities. Monitoring data collected by implementing agencies in HIM districts (not shown) show that a total of 877 villages received BCC interventions through 851 wall paintings, 12 000 IPC meetings and 819 street dramas.

Unlike the HIM intervention, the BCC strategy used in the LIM intervention was focused on increasing access to safe abortion services in 949 villages through community intermediaries and wall signs. A total of 822 community intermediaries, including auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and accredited social health activists (ASHAs), were oriented on the legality and availability of abortion services, consequences of unsafe abortion, safe abortion methods including MVA and medical methods of abortion (MMA) and safety of first trimester abortion. Each of these intermediaries was also oriented on how to refer women requesting termination of pregnancy to a nearby health facility. In addition to this, 487 wall signs were displayed in the most populous villages within the LIM districts.

Study design and sample

A pre–post quasi-experimental research design was used. Cross-sectional household surveys were administered in intervention and comparison districts prior to implementation of the BCC (HIM and comparison districts: 2008; LIM districts: 2009), and once again in 2011 after completion of the intervention (endline). In order to assess message recall, endline surveys were implemented in all six districts 3–6 months after completion of BCC activities.

Women were selected from the intervention and comparison districts using two-stage stratified random sampling. In the first stage, villages from each of the six districts were selected using probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. For the second stage, a detailed household listing was carried out in each selected village to generate the universe of households with eligible women. Women were eligible to participate in the study if they were married and aged 15–49 years. Women were excluded from the study if they (woman or spouse) had been using a permanent method of contraception, female or male sterilisation, for more than 3 years. Twenty households with eligible women were selected from each sampled village using systematic random sampling. A total of 2131 and 2420 women were successfully surveyed at baseline and endline, respectively, with a response rate of 97% at both time points.

Instruments

The survey instruments drew on those used in earlier community studies in the same locations in Bihar and Jharkhand.12 15 Two structured instruments, a woman's questionnaire and a village questionnaire, were used to collect data in a face-to-face interview. The woman's questionnaire was developed to collect background and household level information of female respondents as well as their reproductive health and abortion experiences, knowledge of legal abortion, sources of safe abortion services and methods of abortion. Abortion experiences were assessed, including their pathways of service usage, method of abortion, complications experienced and quality of care received. An identical set of questions was asked at the time of the endline survey with the addition of new questions related to women’s exposure to the communication intervention, level of intervention exposure and message comprehension. Study instruments were prepared in English and translated into Hindi and pretested.

Analysis

Since the sampled districts of Bihar and Jharkhand had similar sociodemographic profiles, the districts in each group (HIM intervention, LIM intervention and comparison) were pooled across states. First, the sociodemographic profile of each group is presented for the baseline and endline periods. Standard sociodemographic measures are used, including the Standard of Living Index (SLI), which was constructed based on asset ownership, house type, access to modern amenities and landholding as is carried out in the Demographic and Health Surveys. This index was scaled into three categories (low, medium and high standard of living) relative to the SLI of the general population. Second, among women who attempted induced abortion in the past 3 years, the profile of the most recent abortion experience is presented. The bivariate significance of changes between baseline and endline surveys was assessed using χ2 and t-tests assuming an α of 0.05.

Bivariate analyses were carried out using linear regression to understand the association between frequencies of BCC exposure and mean levels of a constructed knowledge index score (KIS). The KIS was developed based on the correct responses to five knowledge parameters: (1) legality of abortion, (2) legal gestational limit, (3) awareness on safe access, (4) awareness on WHO-approved methods of abortion and (5) knowledge on sources of abortion care defined as facilities which can provide abortion services with a trained medical doctor. The index score ranged from zero (those with no correct responses) to five (those with correct responses to all five questions).

To assess programme effectiveness, multivariate difference-in-differences (DD) estimation was used. DD estimation compares the changes in key outcomes between baseline and endline in the intervention and comparison districts to provide evidence of programme effectiveness.16 The outcomes used to assess programme effectiveness were various aspects of knowledge about abortion as well as factors around healthcare usage for abortion. Outcome measures for knowledge were dichotomised into accurate or inaccurate knowledge, and logistic regression models using DD estimation were employed to evaluate these outcomes, adjusting for key sociodemographic characteristics.

All research design, tools and protocols underwent ethical review and were approved by the Centre for Media Studies-IRB in India and Allendale IRB in the USA. Only women who gave informed consent were included in this study, and confidentiality of the participants was protected to the fullest extent possible. Funding for the study was provided from the David and Lucile Packard foundation. The funding agency was not involved in the design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of findings. All data available for sharing are presented in this paper; there are no additional data available.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics are presented for women in HIM, LIM and comparison districts in table 1. While some variations were observed, sociodemographic characteristics of women intervention and comparison districts were similar. Women surveyed were primarily from the lowest socioeconomic strata. However, socioeconomic status improved between baseline and endline in HIM, LIM and comparison districts, with significantly more women in the medium or high standard of living categories at endline, compared to baseline.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of respondents at baseline and endline by types of intervention in Bihar and Jharkhand

| HIM districts |

LIM districts |

Comparison districts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (%) n=702 | EL (%) n=786 | p Value | BL (%) n=720 | EL (%) n=820 | p Value | BL (%) n=709 | EL (%) n=814 | p Value | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 15–19 | 3 | 9 | <0.01 | 10 | 8 | 0.32 | 3 | 10 | <0.01 |

| 20–24 | 20 | 30 | <0.01 | 28 | 27 | 0.72 | 17 | 22 | 0.02 |

| 25–29 | 32 | 27 | 0.05 | 25 | 26 | 0.88 | 30 | 24 | 0.01 |

| 30–34 | 21 | 17 | 0.05 | 17 | 17 | 0.68 | 23 | 20 | 0.16 |

| 35–39 | 17 | 11 | <0.01 | 13 | 12 | 0.42 | 20 | 13 | <0.01 |

| 40 and above | 8 | 7 | 0.75 | 8 | 10 | 0.09 | 8 | 11 | 0.03 |

| Age, in years | |||||||||

| Mean | 28.9 | 27.7 | 27.9 | 28.5 | 29.4 | 29.1 | |||

| (SD) | (6.0) | (7.0) | <0.01 | (7.2) | (7.5) | 0.12 | (6) | (7.6) | 0.40 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Never attended school | 65 | 56 | <0.01 | 70 | 67 | 0.22 | 59 | 65 | 0.03 |

| Primary | 5 | 8 | 0.01 | 8 | 6 | 0.32 | 3 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Middle | 19 | 23 | 0.04 | 17 | 18 | 0.75 | 25 | 20 | 0.01 |

| Secondary | 7 | 8 | 0.66 | 3 | 5 | 0.16 | 9 | 5 | <0.01 |

| Sr. Secondary and above | 4 | 5 | 0.86 | 3 | 5 | 0.03 | 4 | 4 | 0.58 |

| Education, in years | |||||||||

| Mean | 8.1 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 2.5 | |||

| (SD) | (2.9) | (3.2) | 0.02 | (3.0) | (3.3) | <0.01 | (2.7) | (3.0) | <0.01 |

| Religion | |||||||||

| Hindu | 56 | 60 | 0.14 | 50 | 49 | 0.64 | 66 | 62 | 0.07 |

| Muslim | 12 | 17 | <0.01 | 47 | 47 | 0.79 | 10 | 9 | 0.39 |

| Christian | 4 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.34 | 8 | 9 | 0.68 |

| Sarna | 28 | 21 | <0.01 | 3 | 5 | 0.08 | 16 | 21 | <0.01 |

| Caste | |||||||||

| General | 10 | 9 | 0.21 | 11 | 35 | <0.01 | 14 | 11 | 0.18 |

| Scheduled Caste | 9 | 17 | <0.01 | 14 | 12 | 0.32 | 8 | 12 | <0.01 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 34 | 26 | <0.01 | 10 | 9 | 0.63 | 29 | 34 | 0.03 |

| Other Backward Classes | 46 | 48 | 0.46 | 65 | 43 | <0.01 | 50 | 43 | <0.01 |

| Family type | |||||||||

| Nuclear | 47 | 46 | 0.70 | 55 | 59 | 0.197 | 41 | 41 | 0.88 |

| Joint/extended | 53 | 54 | 0.70 | 45 | 42 | 0.19 | 59 | 59 | 0.88 |

| Standard of living index | |||||||||

| Low | 83 | 50 | <0.01 | 66 | 55 | <0.01 | 83 | 74 | <0.01 |

| Medium | 12 | 37 | <0.01 | 25 | 34 | <0.01 | 12 | 20 | <0.01 |

| High | 5 | 14 | <0.01 | 9 | 12 | 0.10 | 5 | 6 | 0.69 |

| Worked in past 3 months | |||||||||

| Yes | 30 | 31 | 0.63 | 91 | 19 | <0.01 | 16 | 33 | <0.01 |

| No | 70 | 69 | 0.63 | 9 | 81 | <0.01 | 85 | 67 | <0.01 |

BL, baseline; EL, endline; HIM, high-intensity model; LIM, low-intensity model.

The mean number of pregnancies was similar at baseline and endline in intervention and comparison districts (not shown). More than 90% of women in the sample had ever been pregnant. On average, women reported more than three live births at both baseline and endline surveys. In response to questions related to induced abortion, almost 11% of women in HIM districts and 9% of women in LIM districts had ever experienced an induced abortion at endline. In general, reporting on abortion (spontaneous and induced) increased between baseline and endline in the HIM and comparison districts, while reports of other reproductive events remained relatively stable across the two time periods and across districts. In HIM districts, 16% of women reported spontaneous abortion and 4% reported induced abortion at baseline, compared to 21% of women who reported spontaneous abortion and 11% who reported induced abortion at endline. Though the proportion of women reporting abortion increased in HIM districts between baseline and endline, the proportion of women reporting pregnancy remained stable at 94%. In LIM districts, the numbers were stable; 14% of women reported spontaneous abortion, 9% reported induced abortion and 95% reported pregnancy at both baseline and endline.

Care-Seeking and usage of abortion services

Analysis of care-seeking and usage of abortion services was carried out among women who reported experiencing induced abortion in the 3 years preceding the survey. Many women reported inducing an abortion at home during the baseline survey. Reporting on self-induction or inducing an abortion at home with the help of friends and relatives decreased significantly from 32% at baseline to 13% at endline in HIM districts, and from 38% at baseline to 17% at endline in LIM districts. However, among those who attempted termination at home, the method varied across intervention districts (table 2). MMA use at home increased between baseline and endline in all three groups, but the change was not statistically significant. Use of traditional methods at home, including herbs, hot oil massage and homemade concoction, decreased significantly from 44% at baseline to 17% at endline in HIM districts, and from 41% at baseline to 25% at endline in LIM districts.

Table 2.

Usage of abortion services, types of providers visited and quality of service provisions for most recent abortion attempt among women who experienced induced abortion in the past 3 years at baseline and endline by intervention districts of Bihar and Jharkhand

| HIM districts |

LIM districts |

Comparison districts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (%) n=28 | EL (%) n=45 | p Value | BL (%) n=45 | EL (%) n=48 | p Value | BL (%) n=33 | EL (%) n=51 | p Value | |

| Attempted termination at home | |||||||||

| Yes | 32 | 13 | 0.05 | 38 | 17 | 0.02 | 58 | 31 | 0.30 |

| No | 68 | 87 | 0.05 | 62 | 83 | 0.02 | 42 | 69 | 0.30 |

| Method used at home* | |||||||||

| Medical method | 56 | 83 | 0.41 | 59 | 75 | 0.21 | 50 | 56 | 0.68 |

| Other—traditional method† | 44 | 17 | 0.05 | 41 | 25 | 0.06 | 50 | 44 | 0.36 |

| Provider who performed MTP | |||||||||

| Medical doctor confirmed as a trained, legal provider | 21 | 30 | 0.43 | 57 | 41 | 0.14 | 35 | 29 | 0.62 |

| Medical doctor not confirmed as a trained, legal provider | 68 | 13 | <0.01 | 30 | 21 | 0.32 | 46 | 16 | <0.01 |

| Health worker (legally not allowed to provide abortion) | 7 | 15 | 0.32 | 5 | 2 | 0.55 | 12 | 31 | 0.06 |

| Informal provider (legally not allowed to provide abortion) | 4 | 43 | <0.01 | 11 | 39 | <0.01 | 8 | 24 | 0.08 |

| Method used for abortion | |||||||||

| Surgical method | 32 | 53 | 0.09 | 71 | 66 | 0.64 | 54 | 47 | 0.56 |

| Medical method (MMA) | 57 | 43 | 0.23 | 25 | 34 | 0.35 | 35 | 31 | 0.76 |

| Other—traditional method† | 11 | 5 | 0.37 | 5 | 0 | – | 12 | 22 | 0.26 |

| Received contraception | |||||||||

| Yes | 39 | 60 | 0.09 | 52 | 59 | 0.52 | 42 | 40 | 0.85 |

| No | 61 | 40 | 0.14 | 48 | 41 | 0.52 | 58 | 60 | 0.85 |

| Postabortion complication | |||||||||

| Yes | 32 | 42 | 0.21 | 20 | 31 | 0.15 | 24 | 29 | 0.82 |

| No | 68 | 56 | 0.81 | 80 | 69 | 0.44 | 76 | 71 | 0.06 |

| Cost of MTP in INR (Median) | 1085 | 1450 | 1600 | 1150 | 1550 | 800 | |||

*Computed among women who attempted induced abortion at home.

†Other—traditional methods include use of herbs, hot oil massage or homemade concoctions.

BL, baseline; EL, endline.

Across the three districts, the proportion of women who received MTP services from legal providers decreased between baseline and endline, and the proportion who received services from informal providers increased significantly (table 2). In HIM districts, surgical abortions increased between baseline and endline, while medical abortion increased in the LIM districts and traditional methods increased in the comparison districts, but these changes were not statistically significant. Postabortion complications increased between baseline and endline in all three groups, but the changes were not statistically significant. The proportion of women receiving postabortion contraception increased between baseline and endline in the HIM and LIM districts, but decreased in the comparison districts (changes were not statistically significant). The median cost of MTP services increased between baseline and endline in the HIM and LIM districts and decreased in the comparison districts.

Sources and message recall for abortion-related information

Reported primary source of abortion messages observed reflected the level and types of interventions in each district (data not shown). The primary sources of abortion messages in HIM districts were IPC group or one-on-one meetings (39%), wall signs (35%), street dramas (25%) and neighbours, and relatives (23%) in the HIM districts at endline. One-quarter of women in the HIM districts reported that they were not exposed to the intervention. In comparison, the primary sources of messages in LIM districts were wall signs (39%), neighbours and relatives (15%) and community intermediaries (7%) at endline. Almost half of the women in the LIM districts reported that they were not exposed to the intervention. In the absence of any BCC intervention, an overwhelming majority of women (80%) in the comparison districts reported receiving no messages on abortion-related issues; neighbours and relatives were the primary source of messages at endline (12.2%) in the comparison districts. Thirty-six per cent of women in HIM districts reported being exposed to at least one BCC activity, compared to only 27% of those in LIM districts. Furthermore, 31% of women in HIM districts reported being exposed to more than one activity, while only 6% of women in the LIM districts reported the same (data not shown).

Message recall

Women who reported receiving messages on abortion-related issues through any BCC activities during the past year were asked further to recall the specific information they received. In the intervention districts, women almost uniformly (96% in HIM and 92% in LIM) reported at least one correct message. Conversely, approximately two-thirds of women (69%) in the comparison districts who reported receiving any information on abortion-related issues could not recall any correct information. Women of HIM and LIM districts frequently recalled ‘early abortion as safe’, ‘legality of abortion’, ‘nearest source of safe abortion’, ‘abortion can be done by taking tablets’ and ‘illegality of sex selection’. In the absence of any BCC intervention, women of comparison districts frequently mentioned receiving information on ‘sex selection’ and ‘tablet as a method of abortion’ (data not shown).

Awareness and knowledge on abortion-related issues

Findings show an improvement in awareness and knowledge on the subject of abortion legality in HIM and LIM intervention districts. The proportion of women who reported abortion is legal in India increased significantly from 41% to 63% and 20% to 59% between baseline and endline in the HIM and LIM districts, while it remained constant in the comparison districts. Accurate knowledge of 20 weeks as the legal gestational age limit also increased significantly from 3% at baseline to 6% at endline in HIM districts, and from 0% at baseline to 4% at endline in LIM districts; no change was observed in comparison districts. However, accurate knowledge of the legal gestational age limit remained low overall. Although the BCC campaign tried to reinforce 20 weeks as the legal gestational age limit, many women responded to 12 weeks as the legal limit (table 3).

Table 3.

Awareness and knowledge on legal aspects and abortion methods at baseline and endline by intervention and comparison districts of Bihar and Jharkhand

| HIM districts |

LIM districts |

Comparison districts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (%) n=702 | EL (%) n=786 | p Value | BL (%) n=720 | EL (%) n=820 | p Value | BL (%) n=709 | EL (%) n=814 | p Value | |

| Aware that abortion is legal | |||||||||

| Yes, legal | 41 | 63 | <0.01 | 20 | 59 | <0.01 | 41 | 41 | 0.98 |

| No, illegal | 48 | 15 | <0.01 | 13 | 13 | 0.63 | 48 | 17 | <0.01 |

| No idea/Do not know | 12 | 22 | <0.01 | 68 | 28 | <0.01 | 11 | 42 | <0.01 |

| Knowledge on legal gestational age limit | |||||||||

| 20 weeks | 3 | 6 | 0.01 | 0 | 4 | <0.01 | 1 | 2 | 0.29 |

| 12 weeks | 38 | 29 | <0.01 | 4 | 36 | <0.01 | 37 | 22 | <0.01 |

| Other responses/No idea | 60 | 66 | 0.02 | 96 | 61 | <0.01 | 63 | 76 | <0.01 |

| Know both abortion is legal and legal gestational age limit | 0 | 5 | <0.01 | 0 | 3 | <0.01 | 1 | 2 | 0.082 |

| Know legal sources of abortion services | 45 | 49 | 0.12 | 20 | 30 | <0.01 | 43 | 39 | 0.08 |

| Know both abortion is legal and legal sources of abortion services | 21 | 35 | <0.01 | 6 | 21 | <0.01 | 21 | 20 | 0.49 |

| Know all three: abortion is legal, legal gestational age limit and legal sources of abortion services | 0 | 3 | <0.01 | 0 | 2 | 0.03 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

BL, baseline; EL, endline.

Knowledge of where to access abortion services also increased significantly only in LIM districts, while knowledge decreased in the comparison districts. The greatest increase in knowledge was observed in women who knew that abortion was legal and knew where abortion services were available (14% in HIM districts and 15% in LIM districts). The proportion of women who knew that abortion was legal, the correct gestational age limit and who knew where abortion services were available increased across all districts, but levels remained low (table 3).

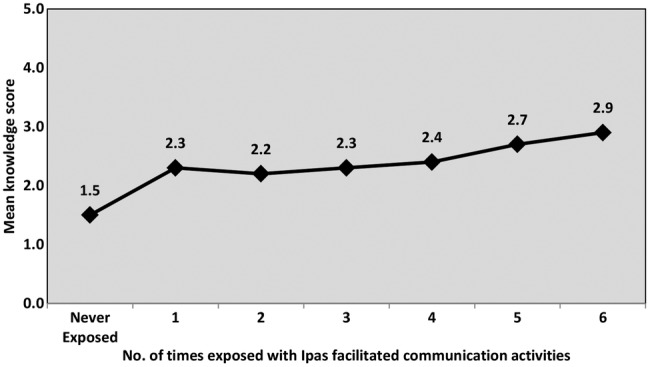

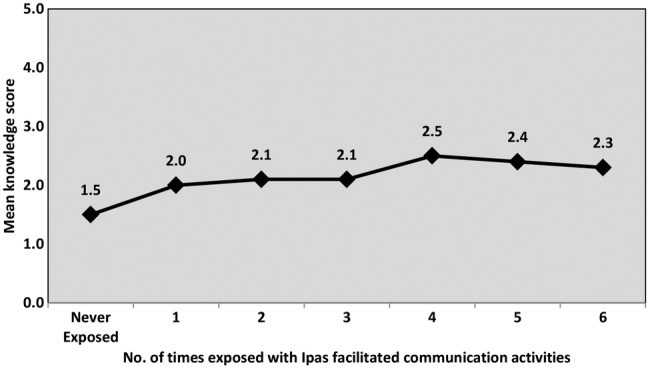

Intervention effects on abortion-related awareness and knowledge

A dose–response relationship was observed between level of exposure to programme activities and knowledge about the legal status of abortion. In the HIM districts, 80% of women who were exposed to three different types of abortion messaging knew that abortion was legal compared to 69% of those who were exposed twice, 67% who were exposed once and 53% who were not exposed. A similar pattern was observed in the LIM districts. Knowledge of the correct legal gestational age limit for abortion was higher among those who were exposed to at least one activity, but did not demonstrate a dose–response relationship. Higher level of exposure did not increase the proportion of women with accurate knowledge of the legal gestational age limit. In the HIM districts, women who were exposed to the IPC activity, wall sign and street drama had the highest proportion who knew that abortion is legal. The association between KIS and level of exposure is plotted in figure 1 for HIM districts and in figure 2 for LIM districts. Overall, a positive linear relationship was observed between the number of times a woman reported exposure to an Ipas-facilitated communication activity and her mean knowledge score in the intervention districts. These positive linear relationships between the number of times a woman reported exposure to an Ipas-facilitated communication activity and her mean knowledge score were similar across HIM and LIM intervention models, but the magnitude of the increase was somewhat higher in HIM districts.

Figure 1.

Level of exposure and mean Knowledge Index Score (KIS) in HIM districts (n=586). HIM, high-intensity model.

Figure 2.

Level of exposure and mean Knowledge Index Score (KIS) in LIM districts (n=450). LIM, low-intensity model.

Effects of the intervention on women's awareness of the legality of abortion: multivariate analysis using the DD model

The results of the DD multivariate analyses are presented in table 4. Between baseline and endline, women living in the HIM districts had a significant increase in their knowledge that abortion is legal (OR: 2.2, p<0.001), knowledge of a source of abortion services (OR: 1.7, p<0.001), knowledge both that abortion is legal and of a legal source of abortion services (OR: 2.2 p<0.001) and knowledge both that abortion is legal and the legal gestational age limit (OR: 12.5, p<=0.05). However, the same pattern of intervention effect is not observed in the LIM districts. The only significant increase was in women's knowledge of a medical method of abortion (OR: 1.8, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Effects of intervention on women's awareness of the legality of abortion and knowledge on safe source and methods using the DD model

| Dependent variables | HIM districts |

LIM districts |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odd ratio (Exp-β) | SE | 95% CI | Odd ratio (Exp-β) | SE | 95% CI | |

| Know abortion is legal | 2.2*** | 0.15 | 1.6 to 2.9 | 1.1 | 0.18 | 0.8 to 1.6 |

| Know legal gestational age limit of 20 weeks | 1.2 | 0.55 | 0.4 to 3.6 | 2.3 | 1.06 | 0.3 to 19 |

| Know abortion is legal and legal gestational age limit | 12.5* | 1.17 | 1.3 to 124 | 2.1 | 1.07 | 0.3 to 18 |

| Know a legal source of abortion services | 1.7*** | 0.15 | 1.2 to 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.17 | 1.0 to 1.9 |

| Know abortion is legal and legal source of abortion services | 2.2*** | 0.17 | 1.6 to 3.2 | 0.6 | 0.29 | 0.4 to 1.1 |

| Know surgical method of abortion | 0.3* | 0.70 | 0.1 to 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.30 | 0.4 to 1.5 |

| Know medical method of abortion | 0.9 | 0.20 | 0.6 to 1.4 | 1.8*** | 0.17 | 1.2 to 2.5 |

*p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

DD, differences-in-differences.

Discussion

This intervention was successful in improving knowledge about the legal aspects of abortion and where to access safe abortion services. Though both intervention types improved some aspects of abortion knowledge, the HIM model was most effective in improving comprehensive knowledge about abortion. The DD analysis showed that after adjusting for key sociodemographic characteristics, there were significant improvements in knowledge under the HIM model compared to the comparison group, especially knowledge of the legal status of abortion in India and nearby sources of safe abortion services. The LIM model was less successful than the HIM model in improving knowledge; only increasing knowledge about medical abortion methods compared to the comparison group. These differences in knowledge are likely to be a result of the nature and intensity of the intervention; women in the HIM districts often received information through interactive intervention components (IPC and street dramas), while women in the LIM districts were most commonly exposed to wall signs, which foster more passive learning. Concerning message recall and penetration, exposure to intervention resulted in recalling at least one correct message.

The study also found evidence of a dose–response relationship between level of exposure to abortion-related messages and accurate knowledge about abortion. In the HIM and LIM models, there was a positive linear relationship between the number of times a woman was exposed to BCC events and her knowledge of abortion. However, different relationships were seen between level of exposure and accurate knowledge depending on the type of message. For example, women with any exposure to an intervention had significantly higher odds of recalling that abortion is legal, but not that of the legal gestational age limit of 20 weeks. These findings are in line with earlier research in India that shows that women who are exposed to multiple message formats had higher odds of knowing the legal gestational age limit for abortion than women with no or a single exposure.4

There is mixed evidence on changes in the usage of safe abortion services between baseline and endline, and these results should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. Though not statistically significant, in HIM districts surgical abortions increased between baseline and endline, while medical abortion increased in the LIM districts and traditional methods increased in the comparison districts. Though it is encouraging that use of more modern abortion methods increased in the intervention districts, there was also evidence that use of informal providers and the percentage of women reporting postabortion complications increased between baseline and endline in all three districts. It is possible that even with increased knowledge about the legal aspects of abortion due to the intervention, women may still prefer to access abortion services from informal providers, such as medical shops and rural medical practitioners, due to the low cost and shorter waiting time compared to the formal health sector. More research is needed to understand whether increases in knowledge can change women's preferences for where to access abortion care. Similarly, the increase in postabortion complications can most likely be explained by the use of MMA, which may often be obtained from informal providers. It is possible that women are given less effective abortifacient drugs, especially if they do not have resources for the more expensive mifepristone-misoprostol regimen and they experience complications such as incomplete abortion due to decreased efficacy.17 It is also possible that high-quality drugs are given, but women are not appropriately counselled on how to take the medication.17

Our findings should be viewed within the context of the study's limitations. Like other demographic and social surveys, the incidence of abortion and abortion-related information may be under-reported. The findings of this study are based on six selected districts and cannot be generalised to the whole of Bihar and Jharkhand. Owing to the small number of women who had abortions within the past 3 years (98 at baseline and 129 at endline), power to detect changes in behaviour is very low. The DD analysis of knowledge that abortion is legal and knowledge of the legal gestational age limit have low power, and null results for these two variables should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the DD model assumes that any ongoing interventions were in place at the time of both the baseline and endline surveys. We are unaware of other abortion-focused interventions conducted by the government or other non-governmental organisations in the selected districts, but this could be a limitation of the study if other interventions started between the baseline and endline surveys. The dose–response findings should also be interpreted with caution due to the small number of women with high frequency of exposures (five or six exposures) to the intervention.

This evaluation suggests that the HIM model is more effective than the LIM model in increasing comprehensive knowledge about safe abortion services. In addition, as has been demonstrated in other BCC literature,18 there is a dose–response of multiple exposures to BCC messages and women's knowledge. Despite significant increases in knowledge, our study found mixed evidence on behaviour change related to abortion services, which is in line with other BCC interventions in India that have found limited impact on behaviour change.5 Our research was not powered to detect changes in behaviour, and more research is needed to understand how BCC interventions can change abortion care-seeking behaviours to ensure that women seek safe abortion services in lieu of informal services that may be more likely to lead to postabortion complications. This study finds that to increase abortion knowledge, interventions should focus on multiple exposures to BCC activities to ensure accurate knowledge, especially of complex concepts such as the legal gestational age limit. The HIM intervention was more effective than the LIM intervention in increasing comprehensive knowledge about safe abortion services. Though the HIM intervention requires a greater investment of resources, it is likely to result in better outcomes than the LIM intervention. Integrating the BCC strategies into the existing cadre of health intermediaries (eg, ASHAs) may offer a sustainable strategy for ensuring multiple exposures to safe abortion messages. However, orientation of health intermediaries in isolation (with few other BCC activities), as in the LIM districts, is unlikely to have an impact. BCC efforts to increase comprehensive abortion knowledge should be paired with increased availability of women-centred abortion services at the primary health centre level to ensure that women have access to high-quality services.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Vinoj Manning, Executive Director, Ipas Development Foundation, for his invaluable contribution to the design and interpretation of findings. This study was supported by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. This article is a derivative of and incorporates significant portions of an Ipas India report11 by Banerjee SK, et al The creation and publication of this derivative work and use of such content is carried out with the permission of and under license from Ipas.

Footnotes

Contributors: SKB oversaw data collection and contributed to the study design, analysis, interpretation of findings and writing of the manuscript. KA contributed to the study design, interpretation of findings and writing. EP contributed to the analysis, interpretation of findings and writing. JW contributed to the data collection and analysis. DUK contributed to the study design, implementation of activities and interpretation of findings. SB contributed to the study design, implementation of activities and interpretation of findings.

Funding: David and Lucile Packard Foundation (Grant number 2009-34564).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: CMS IRB, New Delhi, India and Allendale Investigational Review Board (AIRB) Old Lyme, CT, United States.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Registrar General of India. Maternal mortality in India: 1997–2003. Trends, causes and risk factors. New Delhi: Registrar General of India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggal R, Ramachandran V. The abortion assessment project–India: key findings and recommendations. Reprod Health Matters 2004;12:122–9. 10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston HB. Abortion practice in India: a review of literature. Mumbai, India: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee SK, Andersen KL, Buchanan RM et al. Woman-centered research on access to safe abortion services and implications for behavioral change communication interventions: a cross-sectional study of women in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. BMC Public Health 2012;12:175 10.1186/1471-2458-12-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sood S, Shefner-Rogers C, Sengupta M. The impact of a mass media campaign on HIV/AIDS knowledge and behavior change in North India: results from a longitudinal study. Asian J Commun 2006;16:231–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel EE, Masilamani R, Rahman M. The effect of community-based reproductive health communication interventions on contraceptive use among young married couples in Bihar, India. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2008;34:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MEASURE Evaluation PRH. Family Planning and Reproductive Health Indicators Database 2012.

- 8.Pathfinder International. Straight to the point: Evaluation of Behavior Change Activities. Change Starts Here. Training material-Monitoring & evaluation. Watertown, MA: Pathfinder International, 2014. https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/05/StraightToThePoint_Pathfinder_Tool_2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.West P. Cost-Effectiveness of Regional HIV and AIDS Behaviour Change Communication (BCC). Programme, DFID South Africa, Final Report London: DFID Human Development Resource Centre, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee SK, Andersen KL, Warvadekar J et al. Effectiveness of a behavior change communication intervention to improve knowledge and perceptions about abortion in Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2013;39:142–51. 10.1363/3914213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee SK, Andersen KL, Warvadekar J et al. Sharing messages about safe abortion services: evaluating the Ipas BCC intervention in Bihar and Jharkhand. New Delhi, India: Ipas India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee SK, Andersen K, Mondal S. Knowledge and care seeking behavior of safe abortion in four selected districts of Bihar and Jharkhand, India Population Association of America Annual Meeting Detroit, MI, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aich P, Banerjee SK, Jha TK et al. Situation analysis of MTP services in Bihar. Delhi: Ipas India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aich P, Banerjee SK, Jha TK, et alet al. Situation analysis of MTP services in Jharkhand. New Delhi: Ipas India; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganatra B, Banerjee SK. Expanding community-based access to medical abortion in Jharkhand: a pre-intervention baseline survey in selected two blocks of Ranchi and Khunti Districts. New Delhi, India: Ipas India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gertler PJ, Martinez S, Premand P et al. Impact evaluation in practice. Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. 2011. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2550 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganatra B, Manning V, Pallipamulla SP. Availability of medical abortion pills and the role of chemists: a study from Bihar and Jharkhand, India. Reprod Health Matters 2005;13:65–74. 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26215-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertrand JT, O'Reilly K, Denison J et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries. Health Educ Res 2006;21:567–97. 10.1093/her/cyl036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]