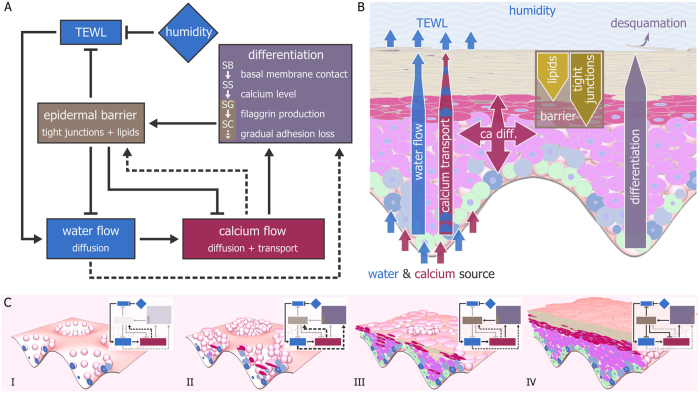

Figure 2. Cells in the model self-organize into a layered epidermis through several regulatory feedback loops.

(A) The core regulatory feedback loops underlying the model. The global parameter humidity (H) inversely affects trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL), which directly affects water flow and indirectly calcium flow (solid arrows). Without the epidermal barrier, water and calcium levels decrease, triggering non-homeostatic differentiation and barrier formation (dashed arrows). The epidermal barrier locally slows down TEWL, water flow, and calcium flow, allowing calcium to accumulate in the SS to trigger homeostatic differentiation (solid arrows). Differentiated cells in the SG and SC build up the barrier in homeostasis. The negative feedback loop between calcium flow and the epidermal barrier ensures a constant homeostatic thickness of the tissue. (B) Schematic representation showing the spatial organization of the barrier, water, and calcium flow in homeostasis. Cells in contact with the basal membrane have access to a source of water and calcium. Due to TEWL, surface cells lose water, which triggers apical water flow by diffusion and calcium flow by directed transport coupled to the water flow. Calcium transport is counteracted by diffusion. Water and calcium flow are locally reduced by the barrier, which consists of stacks of flattened SG and SC cells containing tight junctions (SG and SC) or lipids (SC). The barrier leads to local calcium accumulation in the underlying cells. (C) Different regulatory loops become active as the model epidermis grows from a few stem cells (I) to a full homeostatic tissue (IV). Initially, the epidermal barrier is absent, leading to uncontrolled water and calcium flow (I). This activates the non-homeostatic rescue mechanisms (dashed arrows), which build a transient ectopic barrier (II and III). This transient barrier shields the underlying layers, which can differentiate normally (IV).