Abstract

Hyperbilirubinemia is a common finding in individuals with a history of substance abuse. Although this may indicate a serious disorder of liver function, this is not always the case. An understanding of bilirubin formation, metabolism, and transport can provide a helpful approach to dealing with these patients. This is typified by studies of patients treated with the antiretroviral drug atazanavir. Atazanavir has been associated with hyperbilirubinemia in as many as one-third of individuals for whom it has been prescribed, evoking concerns of hepatotoxicity. The studies in this report were designed to determine mechanisms by which this occurs. The data show that this drug inhibits the enzyme UDP-glucuronosyl transferase-1A1, responsible for conjugating bilirubin with glucuronic acid. This conjugation step is required for bilirubin excretion into bile and when it is inhibited, bilirubin refluxes from the liver into the circulation, causing unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Other parameters of bilirubin formation, binding to albumin in the circulation, uptake into hepatocytes, and intracellular protein binding in hepatocytes were unaffected by atazanavir. The effect of atazanavir on serum bilirubin levels is reversible, consistent with lack of structural damage to the liver.

Keywords: hyperbilirubinemia, atazanavir, UDP-glucuronosyl transferase, drug toxicity, transport

Introduction

Abnormal liver function tests are frequently found in individuals with a history of substance abuse. This includes elevated serum bilirubin levels (hyperbilirubinemia). Although hyperbilirubinemia may indicate a serious disorder of liver function, this is not always the case. An understanding of bilirubin formation, metabolism, and transport can provide a helpful approach to differentiating the various potential causes of hyperbilirubinemia in these patients. An example of the usefulness of this approach is seen in the present studies of patients treated with the antiretroviral drug atazanavir. As many as one-third of individuals taking atazanavir develop hyperbilirubinemia, evoking concerns of hepatotoxicity. Determination of the mechanism by which this occurs is the subject of the present investigation. The approach taken in these studies provides a paradigm that may be of importance in elucidation of causes of hyperbilirubinemia in all patients, including substance abusers who are at risk for exposure to many potential hepatotoxic agents and viruses. Previous studies have indicated that the pathogenesis of hyperbilirubinemia may be multifactorial. That is, it can result from increased bilirubin production or abnormalities in any of the discrete steps of hepatic bilirubin processing, including uptake from the circulation, intracellular binding, conjugation, or biliary excretion1, 2. It is clear that many or all of these processes may be affected in complex clinical disorders, including hepatitis or cirrhosis. However, there are situations, such as inheritable disorders and specific drug inhibitors, in which disruption of a specific step of bilirubin processing may result in hyperbilirubinemia1, 3. In the present study, the effect of atazanavir on the component steps of the bilirubin pathway were determined.

Materials and Methods

Serum Samples

Serum samples from a concluded clinical study (A1424-028) were provided to us by Bristol-Myers Squibb for further analysis4. In that study, 16 healthy volunteers had received atazanavir (200 or 400 mg) once daily for 6 days, followed by coadministration of ritonavir (100 or 200 mg) once daily for 10 days. Blood samples were collected on days 0, 1, 6 and 16 after initiation of treatment. After 16 days of administration, the drugs were discontinued. A follow-up sample was collected on day 20.

Assay of Serum Bilirubin

Serum total bilirubin levels were determined by the Sigma Clinical Kit and values were confirmed by treatment with ethylanthranilate diazo reagent followed by thin-layer chromatography5. The percentage of conjugated bilirubin in serum samples was determined by HPLC. Total bile pigments were extracted from serum by adjusting the pH to 1.4, adding ascorbic acid, and saturating with sodium chloride. The pigments were extracted by shaking vigorously with an equal volume of chloroform:ethanol (1:1, v:v). The organic phase was evaporated by flushing with nitrogen. The pigments were dissolved in a small volume of dimethylsulfoxide and analyzed by reverse-phase high pressure liquid chromatography on a C-18 column as described6. The pigments were quantified from the integrated areas under the peaks.

Effect of Atazanavir Administration on Serum Bilirubin Levels in Gunn Rats and Wistar Rat Controls

Gunn rats are a Wistar rat strain lacking UDP-glucuronosyl transferase-1A1 (UGT1A1) activity. They consequently are unable to conjugate bilirubin and have unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Gunn rats are models of human patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type1. In these studies, six Gunn rats and six congeneic normal Wistar rats (250 g, either gender) 600 or 1200 mg/kg of atazanavir (kindly provided by BMS) suspended in polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG400) was administered by gavage once daily for 16 days. Bilirubin levels were determined using a Sigma diagnostic kit. In additional studies, eight Gunn rats were injected with 5 x 1011 particles (~1 x 1010 pfu) of a recombinant adenovirus, Ad-CTLA4Ig-hUGT1A1, that expresses both the immunomodulatory fusion protein CTLA4Ig and human UGT1A1. We have shown previously that a single injection of this virus stably reduces plasma bilirubin levels in Gunn rats from a mean pretreatment level of 7–8 mg/dl to below 1.0 mg/dl for at least 6 months7. After two weeks, when plasma bilirubin levels were demonstrated to be stably reduced to below 1 mg/dl, four rats were gavaged with 600 mg/kg daily of atazanavir suspended in PEG400 for 16 days. The four other rats, treated with Ad-CTLA4Ig-hUGT1A1 as described, were gavaged with PEG alone (control). All studies were approved by the institutional animal use committee.

Interaction of Atazanavir with Glutathione S-transferases

Preparation of Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) and Assay of Enzymatic Activity

Recombinant human GSTs were expressed in E. Coli and purified by standard glutathione (GSH)-affinity chromatography methods8. Representative GSTs from the 3-major subclasses Alpha (hGSTA1, hGSTA2), Mu (hGSTM2) and Pi (hGSTP1) were purified and characterized by gel-electrophoretic and HPLC methods. Specific activities were determined using 1-chloro 2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) as substrate. Catalytic activities in this study were determined spectrophotometrically by measuring increases in absorbance at 343 nm (Δ A343nm). To evaluate whether the drug itself might interfere with the GST-CDNB spectrophotometric assay at 343 nm, and determine the limits of inhibitor concentrations to be used for the assay, absorbance measurements were performed with the various dilutions of the stock solution of Atazanavir.

Effect of Atazanavir on Binding of Bilirubin to GSTs

Bilirubin binding to GSTs was determined by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Characteristic CD spectra in the spectral region between 500 and 350 nm are generated by asymmetric binding of the bilirubin chromophore to the protein. The proteins alone, which lack a chromophore in this region and the symmetrical bilirubin alone, do not generate the spectra. Relative affinities of atazanavir for GSTs were quantified on the basis of their displacement of bound bilirubin as determined by CD spectra9.

Influence of Atazanavir on Bilirubin Transport by Rat Hepatocytes

Preparation of Isolated Rat Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes were isolated from 200–250 g male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) after perfusion of the liver with Collagenase Type I (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Freehold, NJ)10. All animals used in this study received humane care in compliance with the institution’s guidelines. Viability of isolated hepatocytes was >90% as judged by trypan blue exclusion.

Culture of Isolated Rat Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes were cultured overnight as described previously10, 11. In brief, freshly isolated hepatocytes were suspended in Waymouth’s 752/1 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Calabasas, CA), 1.7 mM additional CaCl2, 5 μg/ml bovine insulin (Sigma), 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco), 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), and 25mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.2. Approximately 1.5 x 106 cells in 3 ml of medium were placed in 60 mm Primaria culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and cultured in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37° C. After 2 hours, the medium was changed and cells were cultured overnight for approximately 18 hours.

Transport of 3H-Bilirubin

3H-Bilirubin was prepared and bilirubin uptake by hepatocytes was quantified as we have described previously12. In brief, cells were washed 3 times with 1.5 ml of serum free medium (SFM) consisting of 135 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.81 mM MgSO4, 27.8 mM Glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.2. They were then incubated for 15 min at 37°C in 1 ml of SFM containing 0.1 % bovine serum albumin (BSA). After this period, cells were incubated for varied periods of time at 4°C or 37°C with 1 ml of SFM containing 0.1% BSA and 1 μM 3H-Bilirubin. Following this incubation, the solution was rapidly aspirated and cells were washed five times at 4°C with 1.5 ml of SFM. The third wash contained 5 % BSA and was allowed to stand for 5 min. Cells were harvested and radioactivity was determined. Cell protein was determined in replicate plates by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA, Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using BSA as standard. Studies were also performed to examine the effect of atazanavir (0.01 – 125 μM) on bilirubin transport. A stock solution of 10mM atazanavir was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and an appropriate aliquot was added to cells simultaneously with 3H-Bilirubin. The bilirubin transport assay was then conducted as described above, and results obtained in the presence of atazanavir were compared to those obtained in its absence.

Results

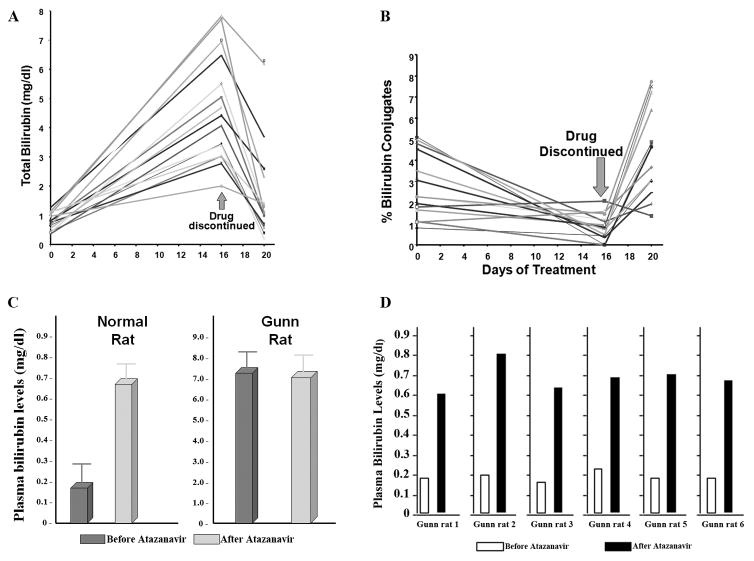

Effect of Atazanavir on Serum Bilirubin in Normal Human Controls

In all individuals, the total serum bilirubin levels increased progressively during the 16 day treatment period. The difference between the concentrations at days 0 and 16 was highly significant (p<0.00001). After discontinuation of the drug treatment there was rapid normalization of the serum bilirubin concentration in each individual. The results are shown graphically in Fig. 1A. The percentage of conjugated bilirubin in serum, as determined by HPLC, before, during, and after atazanavir administration, are shown in Figure 1B. The mean percent conjugated serum bilirubin decreased markedly and significantly (p< 0.001) after the treatment, but increased rapidly after discontinuation of the treatment, in some cases somewhat exceeding the values before the beginning of the treatment.

Figure 1. Effect of atazanavir on serum bilirubin levels.

A. Atazanavir was administered to 16 healthy volunteers at a dose of 200 or 400 mg once daily for 6 days, followed by coadministration of ritonavir (100 or 200 mg) once daily for 10 days. Blood samples were collected on days 0, 1, 6 and 16 after initiation of treatment. After 16 days of administration, the drugs were discontinued. A follow-up sample was collected on day 20. Total serum bilirubin was quantified at these times. B. The percentage of conjugated bilirubin in these serum samples was determined by HPLC. C. Normal Wistar rats and Gun rats with absent UDP-glucuronosyl transferase-1A1 (UGT1A1) were given atazanavir at a dose of 600 mg once a day by gavage for 16 days. Total bilirubin levels were determined before and at the end of treatment. Results are presented as mean ± SD. D. Gunn rats were injected with an adenovirus construct that infects hepatocytes resulting in expression of UGT1A1. These rats were then given atazanavir at a dose of 600 mg once a day by gavage for 16 days. Total bilirubin levels were determined before and at the end of atazanavir treatment.

Effect of Atazanavir on Serum Bilirubin in Wistar and Gunn Rats

In normal Wistar rats, mean total plasma bilirubin increased approximately three-fold (p < 0.01) after treatment with atazanavir. In contrast, there was no significant difference between mean plasma bilirubin levels in Gunn rats before and after the course of atazanavir, p > 0.1 (Fig. 1C). Two weeks after adenoviral-mediated transfer of UGT1A1 into Gunn rats, plasma bilirubin levels were reduced to below 0.3 mg/dl. After a course of atazanavir for 16 days, plasma bilirubin levels increased significantly in the each of the six rats receiving human UGT1A1 gene transfer (Fig. 1D).

Interaction of Atazanavir with GSTs

As seen in Table 1, there was no significant effect of atazanavir on catalysis mediated by any of the GSTs that were tested.

Table 1. The effects of atazanavir on glutathione S-transferase (GST) catalysis.

The mean (± S.D.) enzyme activities of various GSTs with and without atazanavir are shown. Enzyme and drug concentrations for each reaction are shown in the table. The specific reaction conditions of each assay are given in the footnotes (superscript A–D). The drug was dissolved in acidified water (pH 1.0) unless otherwise noted.

| Enzyme | (−) Drug | (+) Drug | [GST] (μg/ml) | [Drug] (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hGSTM2‡A | 0.210 ± 0.011 | 0.190 ± 0.013 | 0.051 | 71.5 |

| hGSTM2A | 0.112 ± 0.004 | 0.107 ± 0.014 | 0.051 | 26.0 |

| hGSTM2A | 0.045 ± 0.002 | 0.044 ± 0.003 | 0.026 | 26.0 |

| hGSTA1A,B | 0.348 ± 0.018 | 0.348 ± 0.029 | 1.245 | 13.0 |

| hGSTA1B,C | 0.039 ± 0.001 | 0.044 ± 0.003 | 1.245 | 13.0 |

| hGSTA2C | 0.060 NA | 0.056 NA | 4.495 | 13.0 |

| hGSTA2C | 0.035 NA | 0.033 NA | 1.798 | 13.0 |

| hGSTPiA | 0.264 ± 0.016 | 0.247 ± 0.014 | 0.460 | 1.30 |

| hGSTPiA | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.046 | 1.30 |

| mGSTsC,D | 0.224 NA | 0.215 NA | 1.010 | 13.0 |

| “mGSTsC,D | 0.060 NA | 0.060 NA | 0.101 | 13.0 |

100% EtOH used as solvent for drug

0.1M phosphate buffer pH 6.7, 1mM CDNB and GSH as substrates

90 second preincubation of drug and enzyme prior to start of reaction

10x dilution of 1-chloro 2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) (0.1mM), and glutathione (GSH) (0.1mM) in the assay solution

GSH affinity purified mouse liver cytosol extract

NA = No replicate assays performed

Effect of Atazanavir on Bilirubin Binding to GSTs

For the alpha class GSTs (hGSTA1-1 and hGSTA2-2) a characteristic biphasic CD spectrum with overlapping bands of opposite sign were observed after binding of stoichiometric amounts (one-per subunit) of bilirubin to the protein (Figure 2A). Addition of atazanavir (1.2-fold molar excess) had no substantial effect on the spectra. These data indicated that the bilirubin was not displaced from the protein by the drug at equimolar concentration. There was also no indication that atazanavir itself was bound by the GSTs. Bilirubin binding to hGSTP1-1 was of a lesser affinity and generated a single ellipticity band centered at 450nm. Addition of atazanavir also had no effect on this spectrum (Figure 2B). Similarly, the drug had no effect on bilirubin binding to human serum albumin (Figure 2C) or to hGSTM2-2 (data not shown).

Figure 2. Influence of atazanavir on binding of bilirubin to Glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) and human serum albumin (HSA) as determined by circular dichroism (CD).

A and B. The scans marked 1 are baselines and represent spectra obtained with protein alone. The spectra labeled 2 represent protein (A - hGSTA2, 0.30 mg/ml; B – hGSTP1, 0.46 mg/ml) mixed with equimolar concentrations of bilirubin (per subunit). Spectra numbers 3,4, and 5 were obtained after sequential addition of atazanavir up to a 1:1 drug:bilirubin ratio. C. CD Spectra of human serum albumin (HSA) (2 mg/ml) in 0.1 M phosphate pH 7.0 (B), and after addition of aliquots of bilirubin (1) and indicated amounts of atazanavir (2 and 3). Raw data are expressed as observed ellipticities (θ).

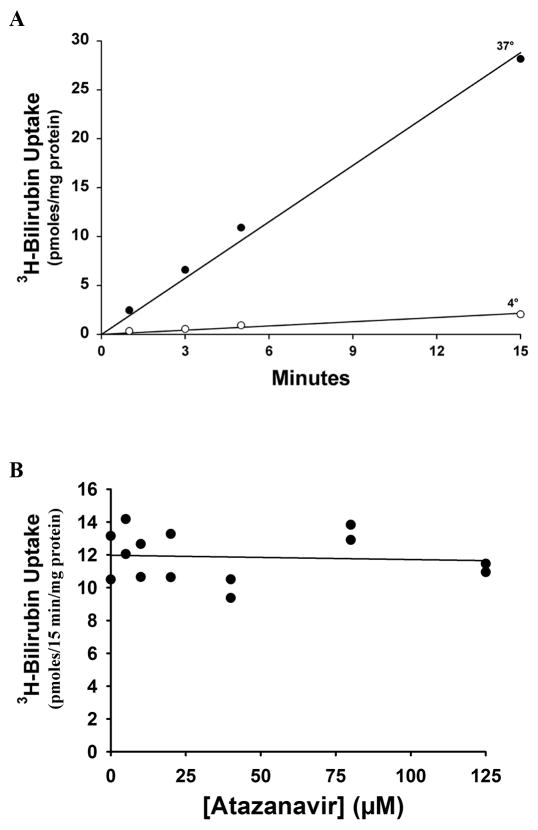

Influence of Atazanavir on Bilirubin Uptake by Hepatocytes

Figure 3A shows that uptake by overnight cultured rat hepatocytes of 1 μM 3H-Bilirubin was highly temperature-dependent and linear for at least 15 min. As seen in Figure 3B, there was no effect of addition of as much as 125 μM atazanavir on bilirubin uptake.

Figure 3. Influence of atazanavir on transport of 3H-Bilirubin by overnight cultured rat hepatocytes.

A. Time and temperature dependence of 3H-Bilirubin uptake in the absence of atazanavir. B. Uptake of 3H-Bilirubin by overnight cultured rat hepatocytes in the presence of varied concentrations of atazanavir, as indicated. Lines represent the least square regression fit to the data.

Discussion

Bilirubin is a degradation product of heme, the bulk of which is derived from hemoglobin of senescent erythrocytes and hepatic hemoproteins1, 2, 13, 14. Bilirubin is insoluble in water because of internal hydrogen bonding. It is potentially toxic, but is normally rendered harmless by binding to plasma albumin, and efficient hepatic clearance and metabolism. Bilirubin toxicity is generally limited to neonates and in subjects with inherited disorders of bilirubin glucuronidation. Nonetheless, accumulation of bilirubin in the plasma may be indicative of liver dysfunction, and the serum bilirubin concentration is a frequently used “liver function test”13. However, hyperbilirubinemia may be relatively benign and can result from altered bilirubin metabolism and does not imply a state of generalized liver damage. In particular, the steps involved in bilirubin elimination need to be considered for designing and interpreting studies to identify the mechanism by which a specific drug can cause hyperbilirubinemia. Bilirubin is carried in the circulation bound to plasma proteins, predominantly albumin2, 13, 14. In the hepatic sinusoids, the albumin-bilirubin complex dissociates and bilirubin is taken up into hepatocytes15. Bilirubin is stored in the hepatocytes bound to cytosolic proteins, particularly glutathione-S-transferases15, 16. In the hepatocyte, the conjugation of bilirubin with glucuronic acid is mediated by UGT1A1, an enzyme that is located in the endoplasmic reticulum2, 3. Conjugated bilirubin is transported across the bile canalicular membrane, and is excreted in the bile2, 17.

In the present study, these steps of bilirubin metabolism were examined in test systems to elucidate the mechanism by which atazanavir administration causes hyperbilirubinemia. These studies show that atazanavir has no effect on binding of bilirubin to albumin, transport of bilirubin across the sinusoidal membrane of hepatocytes, or interaction with the cytosolic binding proteins represented by the GSTs. As seen in Figure 1B, administration of atazanavir to normal human individuals was associated with a decrease in the proportion of bilirubin conjugates in the serum, suggesting that it was inhibiting bilirubin conjugation. This idea was further supported by finding that administration of atazanavir to Wistar rats resulted in a rise of serum bilirubin levels while having no effect on bilirubin levels in Gunn rats, a strain that lacks the ability to conjugate bilirubin (Figure 1C). Adenoviral-mediated bilirubin UGT1A1 gene replacement in Gunn rats restored their sensitivity to atazanavir (Figure 1D). The lack of increase of serum bilirubin concentration in Gunn rats after atazanavir administration was also evidence against a significant contribution of bilirubin overproduction (e.g. hemolysis) in the causation of hyperbilirubinemia after this treatment, as they did not have a rise in serum bilirubin that would be expected had hemolysis been present.

Considered together. these results are most consistent with atazanavir acting as an inhibitor of UGT1A1, resulting in reduced conjugation of bilirubin, thus limiting its ability to be excreted in bile. As in Gilbert or Crigler-Najjar syndromes, genetic disorders characterized by deficient UGT1A1 activity, unconjugated bilirubin can be refluxed back into the circulation resulting in hyperbilirubinemia. The effect of atazanavir on serum bilirubin levels is reversible (Figure 1A), consistent with the lack of structural damage to the liver.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK41296, DK23026, and DK 092469 and by a research grant from Bristol-Myer-Squibb.

The authors thank our colleagues at Bristol-Myer-Squibb for providing serum samples for analysis and atazanavir for these studies.

References

- 1.Wolkoff AW. Mechanisms of hepatocyte organic anion transport. In: Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 5. Academic Press; San Diego: 2012. pp. 1485–1506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy-Chowdhury J, Roy-Chowdhury N. Bilirubin Metabolism and its Disorders. In: Boyer TD, Manns MP, Sanyal AJ, editors. Zakim and Boyer’s Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver Disease. 6. Saunders-Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2012. pp. 1079–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolkoff AW, Berk PD. Bilrubin metabolism and jaundice. In: Schiff ER, Maddrey WC, Sorrell MF, editors. Schiff’s Diseases of the Liver. 11. Wiley; Hoboken: 2012. pp. 120–151. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Mara E, Mummaneni V, Bifano M, Randall D, Uderman H, Knox L, Geraldes M. Pilot study of the interaction between BMS-232632 and ritonavir. In. 8th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Chicago, IL. 2001. Abstract #740. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heirwegh KP, Van Hees GP, Leroy P, Van Roy FP, Jansen FH. Heterogeneity of bile pigment conjugates as revealed by chromatography of their ethyl anthranilate azopigments. Biochem J. 1970;120(4):877–890. doi: 10.1042/bj1200877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy-Chowdhury J, Roy-Chowdhury N, Wu G, Shouval R, Arias IM. Bilirubin mono- and diglucuronide formation by human liver in vitro: assay by high-pressure liquid chromatography. Hepatology. 1981;1(6):622–627. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thummala NR, Ghosh SS, Lee SW, Reddy B, Davidson A, Horwitz MS, Roy-Chowdhury J, Roy-Chowdhury N. A non-immunogenic adenoviral vector, coexpressing CTLA4Ig and bilirubin-uridine-diphosphoglucuronateglucuronosyltransferase permits long-term, repeatable transgene expression in the Gunn rat model of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Gene Ther. 2002;9(15):981–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patskovsky YV, Patskovska LN, Listowsky I. The enhanced affinity for thiolate anion and activation of enzyme-bound glutathione is governed by an arginine residue of human Mu class glutathione S-transferases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(5):3296–3304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamisaka K, Listowsky I, Gatmaitan Z, Arias IM. Interactions of bilirubin and other ligands with ligandin. Biochem. 1975;14:2175–2180. doi: 10.1021/bi00681a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min AD, Johansen KJ, Campbell CG, Wolkoff AW. Role of chloride and intracellular pH on the activity of the rat hepatocyte organic anion transporter. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1496–1502. doi: 10.1172/JCI115159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolkoff AW, Samuelson AC, Johansen KL, Nakata R, Withers DM, Sosiak A. Influence of Cl− on organic anion transport in short-term cultured rat hepatocytes and isolated perfused rat liver. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1259–1268. doi: 10.1172/JCI112946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang P, Kim RB, Roy-Chowdhury J, Wolkoff AW. The human organic anion transport protein SLC21A6 is not sufficient for bilirubin transport. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(23):20695–20699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doumas BT, Eckfeldt JH. Errors in measurement of total bilirubin: a perennial problem. Clin Chem. 1996;42(6 Pt 1):845–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berk PD, Wolkoff AW. Bilirubin Metabolism and the Hyperbilirubinemias. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 1715–1720. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolkoff AW, Goresky CA, Sellin J, Gatmaitan Z, Arias IM. Role of ligandin in transfer of bilirubin from plasma into liver. Am J Physiol. 1979;236(6):E638–E648. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.236.6.E638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolkoff AW, Ketley JN, Waggoner JG, Berk PD, Jakoby WB. Hepatic accumulation and intracellular binding of conjugated bilirubin. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:142–149. doi: 10.1172/JCI108912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jedlitschky G, Leier I, Buchholz U, Hummel-Eisenbeiss J, Burchell B, Keppler D. ATP-dependent transport of bilirubin glucuronides by the multidrug resistance protein mrp1 and its hepatocyte canalicular isoform mrp2. Biochem J. 1997;327:305–310. doi: 10.1042/bj3270305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]