Abstract

The socialization of cultural values, ethnic identity, and prosocial behaviors is examined in a sample of 749 Mexican American adolescents [age 9–12 at the 5th grade; M(SD) = 10.42(.55); 49% female], their mothers, and fathers at the 5th, 7th and 10th grades. Parents’ familism values positively predicted their ethnic socialization practices. Mothers’ ethnic socialization positively predicted adolescents’ ethnic identity, which positively predicted adolescents’ familism. Familism was associated with several types of prosocial tendencies. Adolescents’ material success and personal achievement values were negatively associated with altruistic helping and positively associated with public helping, but not their parents’ corresponding values. Findings support cultural socialization models, asserting that parents’ traditional cultural values influence their socialization practices, youth cultural values, and youth prosocial behaviors.

Keywords: prosocial tendencies, cultural values, Mexican American families

There has been an increasing interest in the impact of the dual cultural adaptations of ethnic minority youths on their mental health, academic outcomes, and resilience (see Gonzales, Fabrett, & Knight, 2009 for a review). One subset of this literature has focused on the role of ethnic or cultural socialization in the culturally related behavior of Latino youths (e.g., Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006; Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993). Although there is a relatively small empirical literature bearing on the changes experienced by Mexican American (or other Latino) youths resulting from ethnic socialization, much of this has focused on the relations between socialization experiences and ethnic identity (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). The development of a strong ethnic identity has consistently been associated with positive psychological outcomes, including prosocial tendencies (e.g., Armenta, Knight, Carlo, & Jacobson, 2010; Supple et al., 2006). There is also an emerging literature focused on the role of ethnic socialization in the transmission of culturally related values in Latino families (e.g., Calderón-Tena, Knight, & Carlo, 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009) and the relation of these values to adjustment (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; Calderón-Tena et al., 2011). However, there is less known about the familial transmission of culturally related values and the associated behavioral changes such as the development of prosocial behaviors (e.g., Calderón-Tena, Knight, & Carlo, 2011; Carlo, Knight, Basilio, & Davis, 2014; Knight, & Carlo, 2012; Knight, Cota, & Bernal 1993). Of particular interest is the inherent motivational processes associated with ethnic identity and cultural values, which may account for individual differences in prosocial tendencies.

The present research is based on theoretical models (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, & Cota, 1993) that emphasize broader cultural and contextual factors including both familial and non-familial socialization agents. Given the plethora of research indicating that family members, and particularly parents, are the foremost source of information about ethnicity for youths (Brown, Tanner-Smith, Lesane-Brown, & Ezell, 2007; Hughes et al., 2006; Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009), we focused on the familial context, including the ethnic and mainstream values endorsed by parents, and parents’ ethnic socialization efforts. Theoretical models of ethnic socialization also highlight developmental differences in the specific features of ethnic identity that are salient at different developmental stages. For example, the greater social and cognitive capabilities associated with adolescence may allow ethnic socialization to foster the more advanced features of ethnic identity such as ethnic identity affirmation (the degree to which one feels that they are a member of the ethnic group), ethnic identity exploration (the degree to which one has tried to learn more about their ethnic group, including the associated values and behavioral expectations), and resolution (the degree to which one has clarified the role that ethnic identity plays in their life; e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). Further, the development of ethnic identity exploration and resolution may be requisite for, and foster, the internalization of values associated with the ethnic culture and the behaviors consistent with those values. Younger children may be motivated to behave in accordance with cultural values because of the associated sanctions. In contrast, with repeated socialization experiences, advancing cognitive development, the development of the capacity to abstract rules from socialization experiences, and the developing awareness that parents’ behavioral expectations have some common and more general threads that apply to a broad set of situations, young adolescents internalize the values associated with their ethnic culture and these preferences facilitate a bias towards specific preferred behaviors. Indeed, there is evidence that late childhood or early adolescence is a time at which important changes in reasoning and values begin to emerge (e.g., Eisenberg, Miller, Shell, McNalley, & Shea, 1991). Our theory of the dual cultural adaptation ethnic minority youth experience (e.g., Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002) suggests that these same developmental achievements are requisite for the internalization of the values, and the associated behavior preferences, of the mainstream culture.

Of particular interest is the notion that cultural values and ethnic identity can also serve as motives for facilitating or mitigating behavioral tendencies. Scholars assert that values are, by definition, motivational, evaluative constructs that can energize and direct subsequent behaviors (e.g., Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987). Because value internalization can result from socialization processes, there may be similarities in value patterns within cultures, and such values can be transmitted from one generation to the next (Carlo & de Guzman, 2009; Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). Importantly, the guiding and motivational elements of values can directly (and indirectly via goals) predict behaviors (e.g., Bardi & Schwartz, 2003). Similarly, scholars have frequently conceptualized identity (including ethnic identity) as a construct that encompasses motivational and preferential qualities that can guide individuals towards and away from specific behavioral tendencies (e.g., Umana-Taylor et al., 2009; Oyserman, Fryberg, & Yoder, 2007). The present study applies cultural socialization and motivation approaches to better understand individual differences in prosocial behaviors among Mexican American youth.

A number of studies demonstrate close links between aspects of Mexican American culture and some types of prosocial behaviors. For example, comparative studies have indicated that Mexican American youth generally cooperatively share resources more with their peers than do their European American counterparts (Knight & Kagan, 1977a, 1977b; Knight, Kagan, & Buriel, 1981; McClintock, 1974; Toda et al., 1978). Further, the children of immigrant Mexican parents are more cooperative than the children of Mexican American parents born in the United States or European American children (de Guzman & Carlo, 2004; Knight, & Kagan, 1977a). Mexican Americans also engage in relatively high levels of a variety of other types of prosocial behaviors (e.g., Calderón-Tena et al., 2011). However, until recently, few studies have examined culture-related mechanisms that might account for such findings.

Conceptually, several culturally related psychological constructs (e.g., familism, ethnic knowledge, religiousness) have been identified as candidates that might predict the development of prosocial behaviors in Mexican American youth (for a review see Carlo et al., 2014). For example, Armenta and colleagues (Armenta, Knight, Carlo, & Jacobson, 2011) have suggested that, in addition to socializing their children to be relatively familistic, highly familistic parents are more likely to: (1) ask their children to do household chores including care-giving of younger siblings, which may encourage compliant prosocial tendencies; (2) be more attuned to the emotional state of family members and provide more emotional support, which may encourage emotional prosocial tendencies; and (3) be more aware of, and provide more support for, extended family members who are in a crisis or emergency situation, which may encourage prosocial tendencies in dire situations. Hence, the internalization of familism values through socialization processes within the family is particularly likely to foster compliant, emotional, and dire prosocial tendencies used within the family, and there is emerging empirical support for the linkages between familism values and these specific types of prosocial tendencies (Armenta et al., 2011; Calderón-Tena et al., 2011). Furthermore, Knight, Carlo, Basilio, and Jacobson (in press) demonstrated that familism values are associated with more frequent perspective taking and suggested that the development of perspective taking capabilities represents a psychological process embedded within the internalization of familism values that may also promote these specific prosocial tendencies both within and outside the family.

Our dual cultural adaptation perspective also suggests that the internalization of more mainstream cultural values (e.g., material success and personal achievement values) are fostered by socialization experiences both within and outside the family context, but to a lesser degree within the family context relative to ethnically related values. Furthermore, the internalization of material success and personal achievement values is particularly likely to motivate different types of prosocial behaviors from those prosocial behaviors promoted by familism values. For example, material success and personal achievement values may particularly foster public prosocial helping because it may lead to others’ approval and enhanced status. In contrast, material success and personal achievement values may inhibit altruistic helping because this form of selfless helping may threaten the achievement of material success and personal achievement.

Furthermore, although there is not a large research literature specifically examining maternal and paternal ethnic socialization, there is evidence that African American mothers engage in higher levels of cultural socialization than do African American fathers and that culture-related parental characteristics and past experiences contribute to their beliefs and cultural socialization practices (Hughes & Chen, 1997; McHale et al., 2006). There is also some evidence that maternal and paternal cultural socialization may be differentially related to youth outcomes, such that maternal cultural socialization was positively related to ethnic identity and paternal cultural socialization was negatively related to depression (McHale et al., 2006). In addition, Mexican American mothers’, but not fathers’, ethnic socialization was associated with adolescents’ ethnic identity two years later (Knight et al., 2011). Given these limited findings we expect that the Mexican American mothers’ ethnic socialization, relative to fathers’ ethnic socialization, will be associated more strongly with their adolescents’ ethnic identity, familism values, and prosocial tendencies.

The Present Study

The present study was designed to test a theoretical model proposing that the familism values of Mexican American mothers and fathers lead them to engage in ethnic socialization that enhances their adolescents’ ethnic identity and familism values and, in turn particularly promotes their adolescents’ emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial tendencies. In addition, this theoretical perspective proposes that the adolescents’ material success and personal achievement values will lead to higher public prosocial tendencies and lower altruistic prosocial tendencies. However, we expect parental and adolescent material success and personal achievement values to be more weakly associated, relative to parental and adolescent familism values, because much of the socialization of these mainstream values is based upon experiences outside the home with non-family members. We also examine the generality of the model by examining whether the model is moderated by adolescents’ gender and nativity.

Method

Participants

Data for this study come from the first, second, and third assessments of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families (see Appendix S1). The data for this project were collected between September 2004 and May 2011. Participants were 749 Mexican American adolescents (49% female), their mothers, and 467 (62.3%) of their fathers selected from the rosters of schools that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Eligible families had a 5th grade child who was not severely learning disabled attending a sampled school. The participating mother was the biological mother, lived with the adolescent, and identified as Mexican origin; the biological father was Mexican origin; and no step-father or mother’s boyfriend (other than the biological father) was living with the adolescent. Out of the 749 families, 570 were two-parent families and 82% of these fathers agreed to participate.

The adolescents ranged in age from 9 to 12 with a mean of 10.42 (SD = .55; with 97.6% being 10 or 11 years old) at the first assessment. Of the 39 (5.2%) families who did not participate at the second assessment (approximately two years later when most of the students were in the 7th grade), 16 (2.1%) refused to participate. Of the 109 (14.6%) families who did not participate at the third assessment (approximately three years later when most of the students were in the 10th grade), 37 (4.9%) refused to participate. Comparisons on several demographic variables revealed no significant differences between the adolescents (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), the mothers (i.e., marital status, age, generational status), and the fathers (i.e., age, generational status) who did and did not complete the second and third assessments.

Procedure

Adolescents, mothers, and fathers completed computer assisted personal interviews at their home, scheduled at the family’s convenience, which were about 2.5 hours long. The interviewers were: 80–90% female; fluent in both English and Spanish; recipients of a master’s or bachelor’s degree (or the combination of education and at least 2 years of professional experience in a social service agency); strong in communication, organizational, and computer skills; and completed at least 40 hours of training. Interviewers read each survey question and possible responses aloud in participants’ preferred language. Participating adolescents were compensated $45 for the first, $50 for the second, and $55 for the third assessment.

Measures

Nativity

In response to the question “In what country were you born?” mothers and fathers were asked to select among three possible options (the United States, Mexico, or other). Mothers also reported on the country of birth of their participating child using these options.

Familism Values and Material Success & Personal Achievement Values

The adolescents, mothers, and fathers completed the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS: Knight et al., 2010) to assess familism values and material success & personal achievement values. These specific MACVS subscales are used in this study because they have been theoretically linked to specific prosocial tendencies. The development of the MACVS was based on the values that Mexican American mother, father, and adolescent focus groups identified as associated with the Mexican American and mainstream U.S. cultures. The familism values scale consists of 3 correlated subscales from MACVS: Familism-Support (6 items, e.g., “parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”); Familism-Obligation (5 items, e.g., “if a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”); and Familism-Referents (5 items, e.g., “a person should always think about their family when making important decisions”). The material success & personal achievement values scale consists of 2 correlated subscales from the MACVS: Material Success (5 items, e.g., “the best way for a person to feel good about himself (herself) is to have a lot of money”); and Personal Achievement (4 items, e.g., “one must be ready to compete with others to get ahead”). Participants` indicated their endorsement of each item by responding with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all to (5) very much. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the items for each subscale fit best on the respective subscale; that these subscales also loaded on these two higher order factors; and that there was strong measurement invariance between the 5th grade adolescents and their mothers and fathers (see Knight et al., 2010 for these details). In addition, adolescent familism values displayed reasonably strong (metric) invariance (CFI = .89, RMSEA = .04, and SRMR = .05), and material success & personal achievement values achieved reasonably strict (scalar) invariance (CFI = .89, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .05), from 5th to 7th grade. Knight et al. (2010) also provide evidence of the validity of the MACVS subscale scores. The Cronbach’s α for the familism values scale was .79 for the mothers, .79 for the fathers, and .80 and .85 for the adolescents at the first and second assessment, respectively. The Cronbach’s α for the material success & personal achievement values scale was .83 for the mothers, .84 for the fathers, and .86 and .85 for the adolescents at the first and second assessment, respectively.

Ethnic Socialization

Mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization was assessed with an adaptation of the 10-item Ethnic Socialization Scale from the Ethnic Identity Questionnaire (e.g., Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993). This measure was designed to assess ethnic socialization about cultural traditions, values, beliefs, and ethnic group history. The adaptation was designed to eliminate items more appropriate for youth younger than those in the present study and to generate a few items specifically focused on the socialization of values that have been associated with a Mexican heritage (Knight et al., 2010). Mothers and fathers were asked to indicate, using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) almost never or never to (5) a lot of the time (frequently), how often had they socialized their adolescent children about the Mexican American culture. Sample items included: “How often do you: tell your child to be proud of his (her) Mexican background”; “tell your child that he (she) always has an obligation to help members of the family”; and “tell your child about the discrimination she (he) may face because of her (his) Mexican background.” Cronbach’s α was .74 for mothers and .75 for fathers.

Ethnic Identity

Adolescents’ ethnic identity was assessed for the first time during the 7th grade (the second assessment) because this was the earliest age at which the item context and structure was developmentally appropriate. The 17-item Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004), which includes three subscales that measure exploration (7 items), resolution (4 items), and affirmation (6 items), was used. Adolescents were asked to indicate how true each item was using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all true to (5) to very true. Because the EIS is designed to be administered to diverse ethnic samples, items were slightly revised for the current study to be specific to individuals of Mexican origin. Sample items included: “You have attended events that have helped you learn more about your Mexican (Mexican American) background” (exploration), “You have a clear sense of what your Mexican (Mexican American) background means to you” (resolution), and “You wish you were of a cultural background that was not Mexican (Mexican American)” (affirmation, reverse scored). Cronbach’s α for adolescents was .73, .86, and .76 for the exploration, resolution, and affirmation subscales, respectively. Although the affirmation subscale has a reasonable internal consistency, confirmatory factor analyses, construct validity analyses, and adolescents’ comments (see White, Umaña-Taylor, Knight, & Zeiders, 2011) led us to believe that the reverse wording of all of the items on this subscale limited the comprehension of these items for many of the relatively young 7th grade Mexican American youth in this sample. Given the findings reported by White et al (2011) we do not believe that these items provided an adequate assessment of ethnic identity affirmation, hence, the affirmation subscale was not included in the current analyses.

Prosocial tendencies

The Prosocial Tendencies Measure - Revised (PTM-R: Carlo, Hausmann, Christiansen, and Randall, 2003) was first administered during the 10th grade (the third assessment) of this longitudinal study. The PTM-R was developed to assess individual tendencies to engage in six different types of prosocial behaviors: emotional (5 items – alpha = .86: e.g., helping when the situation is emotionally evocative), dire (3 items – alpha = .76: e.g., behaving prosocially in emergency situations), compliant (2 items – alpha = .64: e.g., assisting when such behavior is requested or demanded), anonymous (4 items - .76: e.g., helping without being recognized), public (3 items – alpha .75: e.g., helping when observed by others), and altruistic (3 items – alpha = .75: e.g., helping without anticipated self-rewards). Each item describes a type of prosocial behavior and the respondent indicates how characteristic the behavior is of them on a 5-point scale that ranges from “does not describe me at all” to “describes me very well.” Example items include, “When people ask me to help them, I don’t hesitate” (compliant), “It makes me feel good when I can comfort someone who is very upset” (emotional), “I tend to help people who are in a real crisis or need” (dire), “Most of the time, I help others when they do not know who helped them” (anonymous), “I can help others best when people are watching me” (public), and “I think that one of the best things about helping others is that it makes me look good” (altruistic, reverse coded).

Because Cronbach’s alpha is a limited estimate of the internal consistency when a scale has relatively few items, factor analytic evidence is often more useful. A confirmatory factor analysis of the PTM-R six correlated factor structure fit well (CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .04). Several studies have demonstrated the convergent and discriminant construct validity of the PTM (see McGinley, Opal, Richaud, & Mesurado, 2014, for a review) as well as strong factorial invariance across European American and Mexican American adolescents (Carlo, Knight, McGinley, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2010). In addition, the construct validity evidence of the PTM in Mexican Americans samples has also been demonstrated (e.g., Armenta et al., 2011; Carlo et al., 2010; Knight et al., in press). For example, Carlo et al. (2010) provided evidence consistent with theoretically-based expectations that altruistic, anonymous, and compliant helping (but not other types) were positively related to religiousness.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were examined for all study variables (see supplemental material). Emotional, Dire, Compliant and Anonymous prosocial tendencies were highly positively inter-correlated and positively correlated, albeit somewhat lower with public prosocial tendencies (see Supplemental Table S1). In addition, altruistic prosocial tendencies were negatively correlated with the other prosocial tendencies, although this negative correlation was not statistically significant for compliant prosocial tendencies. Table 1 presents the 5th and 7th grade concurrent correlations and the 5th to 7th grade prospective correlations among the mothers’, fathers’, and adolescents’ cultural variables. These correlations are generally consistent with the proposed socialization model. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the mothers’, fathers’, and adolescents’ cultural variables and their correlations with the six prosocial tendencies. Consistent with their cultural background, the prosocial tendency means indicate that the adolescents’ strongly endorsed the emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial tendencies. Although the 5th to 10th grade prospective total correlations of the prosocial tendencies (except for the altruistic prosocial tendencies) with the mother’s fathers’ and adolescents’ cultural variables are mostly non-significant and very modest, the 7th to 10th grade prospective correlations between the adolescents’ cultural variables and the prosocial tendencies were mostly consistent with the proposed model. Hence, the prospective correlations in Tables 1 and 2, taken together, are most consistent with the proposed model.

Table 1.

Correlations among the Observed Family Cultural Orientation Variables.

| 5th Grade | 7th Grade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Mothers | Fathers | Adolescents | Adolescents | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 5th Grade | ||||||||||

| Mothers: | ||||||||||

| 1. Familism Values | ||||||||||

| 2. Material/Achievement Values | .55*** | |||||||||

| 3. Ethnic Socialization | .45*** | .25*** | ||||||||

| Fathers: | ||||||||||

| 4. Familism Values | .23*** | .20*** | .10** | |||||||

| 5. Material/Achievement Values | .23*** | .43*** | .10** | .62*** | ||||||

| 6. Ethnic Socialization | .07 | .06 | .21*** | .32*** | .20*** | |||||

| Adolescents: | ||||||||||

| 7. Familism Values | .02 | .01 | .01 | .06 | .04 | .02 | ||||

| 8. Material/Achievement Values | .06 | .20*** | .03 | .11*** | .07 | .04 | .15*** | |||

| 7th Grade | ||||||||||

| Adolescents: | ||||||||||

| 9. Ethnic Identity | .07 | .03 | .20*** | −.02 | −.00 | .05 | .00 | .00 | ||

| 10. Familism Values | .14*** | .08* | .08* | .10 | .07 | −.02 | .25*** | .05 | .48*** | |

| 11. Material/Achievement | .09* | .22*** | .04 | .12*** | .14*** | .04 | .09* | .62*** | .00 | .17*** |

Note: Material Success/Personal Achievement Values referred to as Material/Achievement Values.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Table 2.

Means (SDs) for the Cultural Variables and Correlations with the Prosocial Tendencies.

| Prosocial Tendencies at 10th grade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Emotional | Dire | Compliant | Anonymous | Public | Altruistic | Mean (SD) | |

| 5th Grade | |||||||

| Mothers: | |||||||

| Familism Values | −.06 | .02 | −.05 | .00 | .08* | −.08* | 4.38 (.39) |

| Material/Achievement Values | −.04 | .01 | −.03 | .00 | .10** | −.15*** | 3.20 (.62) |

| Ethnic Socialization | .02 | .05 | −.01 | .10** | .08 | −.01 | 3.10 (.52) |

| Fathers: | |||||||

| Familism Values | −.05 | .02 | −.05 | .02 | −.01 | −.10** | 4.37 (.40) |

| Material/Achievement Values | −.03 | .02 | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | −.10** | 3.40 (.62) |

| Ethnic Socialization | −.01 | .02 | .02 | .05 | −.02 | −.09* | 2.99 (.54) |

| Adolescents: | |||||||

| Familism Values | .04 | .04 | .02 | .04 | .07 | −.08* | 4.54 (.37) |

| Material/Achievement Values | .00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | .19** | −.26*** | 2.91 (.74) |

| 7th Grade | |||||||

| Adolescents: | |||||||

| Ethnic Identity | .25*** | .28*** | .19*** | .17*** | .02 | .07 | 3.93 (.66) |

| Familism Values | .25*** | .26*** | .16*** | .19*** | .19*** | −.16*** | 4.44 (.40) |

| Material/Achievement Values | .02 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .32*** | −.42*** | 2.74 (.63) |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 3.81 | 3.86 | 3.69 | 3.01 | 2.88 | 3.57 | |

| SD | .78 | .79 | .92 | .90 | .89 | .90 | |

Note: Means and standard deviations are based on observed composite variables. Material Success/Personal Achievement Values referred to as Material/Achievement Values.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Model Testing

The hypothesized model of the socialization of cultural values and prosocial tendencies in Mexican American adolescents was tested through structural equation modeling (SEM) using Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), which employs full information maximum likelihood estimation for handling missing data. All variables were treated as latent variables. Latent variables were identified using subscales as parcels when subscales existed, except for the prosocial tendency scales where single item indicators were used. Two ethnic socialization items were excluded from the model, one because it had a low factor loading and the other because it cross loaded on multiple latent variables. As a result, all factor loadings for each latent variable were above .65 and statistically significant. Adolescents’ reports of familism and material success & personal achievement values at 5th grade were included in all models in order to better assess change in values over time. Variables measured at the same time point were allowed to correlate in the models (e.g., mother and father familism values at the first assessment). We considered the model fit to be good (acceptable) if the SRMR ≤ .05 (.08) and either a RMSEA ≤ .05 (.08) or a CFI ≥ .95 (.90) because simulation studies suggest that this combination rule resulted in low Type I and Type II error rates (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). Modification indices were examined to assess whether additional, non-hypothesized paths should be added to the model.

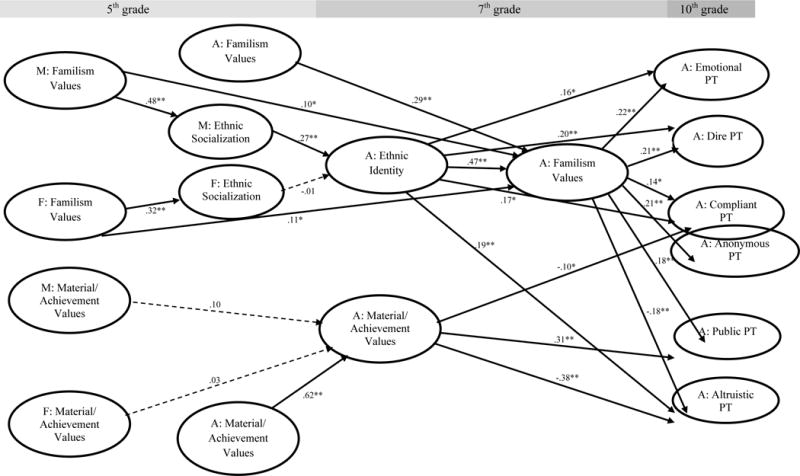

The model proposing how mothers’, fathers’, and adolescents’ familism and material success & personal achievement values were prospectively associated with prosocial tendencies (Figure 1) fit the hypothesized model adequately: CFI = .92, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .05. Mothers’ and fathers’ familism values were positively associated with mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization, respectively, when their child was in the 5th grade. Mothers’ and father’s familism values also predicted adolescents’ familism values in the 7th grade (i.e., familism values at 7th grade after controlling for familism values at 5th grade). Mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade predicted adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade but fathers’ ethnic socialization did not. In turn, adolescents’ ethnic identity was positively associated with adolescents’ familism values at 7th grade. Adolescents’ familism values were positively related to emotional, dire, compliant, anonymous, and public prosocial tendencies and negatively related to altruistic prosocial tendencies.

Figure 1.

Cultural Values Predicting the Prosocial Tendencies of Mexican American Youth.

Note: Standardized betas presented. CFI = .92, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .05. Same time-point correlations, error variances, and non-significant paths (except for those with important theoretical implications) are not shown. M = mother, F = Father, A = Adolescent, PT =Prosocial Tendencies. * p < .05, ** p < .01.

In stark contrast, mothers’ and fathers’ material success & personal achievement values at 5th grade did not significantly predict adolescents’ material success & personal achievement values at 7th grade. Further, adolescents’ material success & personal achievement values only significantly positively predicted public and negatively predicted compliant and altruistic prosocial tendencies. Adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade also significantly predicted emotional, dire, compliant, and altruistic prosocial tendencies at 10th grade.

We conducted a number of additional model tests to determine if constraining specific path coefficients to be equal for mother and father constructs resulted in a significantly poorer fitting model. Although the path coefficient between parental familism values and parental ethnic socialization were substantial and significant for both parents, the mothers path coefficient was significantly higher than the fathers [i.e., the model constraining these path coefficients to be equal for mothers and fathers fit significantly poorer than the model that allowed these path coefficients to be different; Δχ2 (df =1) = 15.85, p < .01]; and the path coefficient from the parental ethnic socialization to the adolescents ethnic identity was significantly higher for mothers than fathers [Δχ2 (df =1) = 5.37, p < .05]. In addition, the path coefficients from parental material success & personal achievement values to adolescents’ material success & personal achievement values were not significantly different for mothers and fathers [Δχ2 (df =1) = .37, p = .54], and the constrained path coefficient was not significant. Although, mothers’ and fathers’ born in Mexico report higher familism values, ethnic socialization, and material success & personal achievement values (correlations reported in Supplemental Table S2 and are consistent with previous findings; Knight et al, 2010); a model including the parents’ nativity as predictors of their endorsement of familism and material success & personal achievement values also fit the data, but did not result in any differences in significance of path coefficients in the reported model. Finally, Wald Tests were conducted to compare the pathways from adolescent familism values versus material success & personal achievement values to the various prosocial tendencies. Findings revealed that the two values systems were significantly different in how they predicted emotional dire compliant and anonymous prosocial tendencies, but similarly predicted public and altruistic prosocial tendencies (see Supplemental material for more detailed information). Given these findings, the subsequent analyses were based upon the model reported herein.

Tests of mediation

After examining the pathways in the structural equation model showing the longitudinal influence of parents’ values to adolescents’ values to adolescents’ prosocial tendencies, mediational analyses were conducted to more formally assess the nature of indirect effects on prosocial tendencies. According to guidelines outlined by MacKinnon (2008), two sets of hypotheses are necessary to establish mediation effects: a) the independent variable should predict the mediator, and b) the mediator should predict the outcome after controlling for the direct effect. When both sets were qualified, the significance of the mediational pathways was tested using the bootstrapping method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

These analyses identified seven significant mediational (i.e., indirect) pathways: one pathway each for emotional, dire, compliant, anonymous, and public prosocial tendencies and two for altruistic prosocial tendencies (see Table 3). The effects of mothers’ familism values at 5th grade on adolescents’ 10th grade emotional prosocial tendencies, dire prosocial tendencies, anonymous prosocial tendencies, and public prosocial tendencies were significantly mediated by mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade, adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade, and adolescents’ familism values at 7th grade. The effect of mothers’ familism values at 5th grade on adolescents’ 10th grade compliant prosocial tendencies was significantly mediated through mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade and adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade.

Table 3.

Significant indirect pathways predicting adolescent prosocial tendencies

| Mediation Pathway | b | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s familism values → A’s emotional prosocial tendencies | .04* | .014 – .102 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s familism values → dire prosocial tendencies | .05* | .018 – .124 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s familism values → anonymous prosocial tendencies | .04* | .012 – .107 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s familism values → public prosocial tendencies | .04* | .010 – .094 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s compliant prosocial tendencies | .09* | .018 – .238 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → A’s familism values → A’s altruistic prosocial tendencies | −.06* | −.134 – .017 |

| M’s familism values → M’s ethnic socialization → A’s ethnic identity → altruistic prosocial tendencies | .12* | .030 – .282 |

Note: Mother’s referred to as M’s. Adolescent’s referred to as A’s.

p < .05

The negative effect of mothers’ familism values at 5th grade on adolescents’ altruistic prosocial tendencies at 10th grade was mediated by two indirect pathways. First, mothers’ familism at 5th grade was associated with mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade, mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade was associated with higher adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade, ethnic identity at 7th grade was associated with adolescents’ familism at 7th grade, and adolescents’ familism values at 7th grade was negatively associated with altruistic tendencies at 10th grade. Second, mothers’ familism values at 5th grade were associated with higher mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade, mothers’ ethnic socialization at 5th grade was associated with higher adolescents’ ethnic identity at 7th grade, and ethnic identity at 7th grade was associated with higher altruistic tendencies at 10th grade.

Tests of Moderation by Gender and Nativity

To evaluate the degree to which the hypothesized model varied by gender or nativity of the adolescent (U.S. versus Mexico-born), two multi-group structural equation models (constrained and unconstrained paths) were computed. A χ2 difference test (Δχ2) was computed to compare the model fit between the constrained and unconstrained models. The non-significant Δχ2 (df = 51) = 53, p =.46 for gender and the non-significant Δχ2 (df = 51) = 50, p =.30 for adolescent nativity, and the relatively similar practical fit indices of the constrained and unconstrained models indicated that the adolescents’ gender and nativity did not significantly moderate the path coefficients. Thus, the tests revealed that the model fit the data equally well for boys and girls, and for U.S. and Mexican born youth.

Discussion

The longitudinal findings supported the proposed theoretical model suggesting that the processes of adaptation to the ethnic culture and adaptation to the U.S. mainstream culture are differentially predictive of different types of prosocial tendencies. However, there was supportive evidence for the associations between mothers, but not fathers, socialization of familism values and prosocial tendencies. These findings provide overall support for a cultural transmission model that suggests the central role of mothers in socializing prosocial behaviors among Mexican American youth. Moreover, the findings provide support for conceptual models that posit the motivational elements of ethnic identity and cultural values as explanatory mechanisms that account for individual differences in prosocial behaviors. To our knowledge, this is the first direct, longitudinal data that provides such evidence.

Specifically, Mexican American mothers (and fathers) who were higher in familism values engaged in more ethnic socialization when their child was in the 5th grade. The mothers who engaged in more ethnic socialization also had adolescents who were higher in ethnic identity in the 7th grade and higher in familism values in the 7th grade (controlling for 5th grade youth familism values). Further, adolescents with greater familism values reported more emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial tendencies at the 10th grade. These adolescents also reported less altruistic tendencies, perhaps because familism values are designed to support and benefit the family, which includes the adolescent. That is, the prosocial actions driven by the socialization of familism values are not likely to be selfless, and because the family as a whole benefits, there are likely to be rewards for the youth. In addition, there were direct effects indicating that adolescents who were higher in ethnic identity at the 7th grade reported more emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial tendencies at 10th grade. Hence, the consistent model findings, across both gender and nativity, suggest that much of the socialization of the Mexican American culture occurs within the family and that this ethnic socialization by the mother is linked to the adolescents’ prosocial tendencies.

Also consistent with the proposed theoretical model, adolescents with more material success & personal achievement values in 7th grade (controlling for these values in the 5th grade) reported more public prosocial tendencies and less altruistic prosocial tendencies in the 10th grade; however their material success & personal achievement values in 7th grade are not related to their mother’s and father’s material success and personal achievement values when the youth was in the 5th grade. These model findings suggest that much of the socialization of mainstream culture may not occur in the family but may be socialized by agents outside the family, and that this mainstream socialization is related to specific types of prosocial tendencies. Furthermore, the associations of material success & personal achievement values with specific types of prosocial tendencies held true across both gender and nativity. Unfortunately, we did not have assessments of non-familial socializing agents that may have predicted the adolescents’ endorsement of material success and personal achievement values.

There were also a few model pathways that we did not expect. First, the adolescent’s familism values in 7th grade were associated with a broader range of 10th grade prosocial tendencies than expected. That is, although the associations between the adolescent’s familism values and the prosocial tendencies theoretically linked to the Mexican American culture (i.e. higher emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial tendencies and lower altruistic prosocial tendencies) were consistent with theory, familism values were also associated with higher levels of public prosocial tendencies, similar to the relation between material success & personal achievement values and public prosocial tendencies. This latter unexpected finding may reflect a tendency for youth who strongly endorse familism to gain the approval of their parents and family members by engaging in prosocial behaviors in a very public way. Furthermore, familism was positively related to helping anonymously. Hence, the socialization of familism values may have a more pervasive effect on a range of prosocial tendencies across contexts and motives (including prosocial tendencies that may be motivated by self-interest) than we hypothesized. Second, in addition to the adolescents’ material success & personal achievement values in 7th grade being associated with the hypothesized 10th grade prosocial tendencies (i.e., higher public prosocial tendencies and lower altruistic tendencies), these values were also modestly associated with lower compliant prosocial tendencies. One might speculate that the adolescents who were high in material success and personal achievement values perceive compliance with requested prosocial behaviors as costly and therefore avoid these actions. However, responding to requests for help should improve one’s stature much the way engagement in public prosocial tendencies may; therefore, such values may result in compliant helping when youth are motivated to improve one’s social status. Also difficult to explain is the positive direct path from the adolescent’s 7th grade ethnic identity to their 10th grade altruistic prosocial tendencies, particularly in light of the countervailing negative indirect path between 7th grade ethnic identity and 10th grade altruistic prosocial tendencies through 7th grade familism values. However, this pattern of relations was consistent with the findings in prior research (Armenta et al., 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that familism values by themselves may narrow one’s willingness to help for selfless reasons unless youth prominently incorporate the concept of being Latino(a) into their broader sense of identity.

The finding that mothers’, compared to fathers’ ethnic socialization, was more strongly associated with the adolescents’ ethnic identity, familism values, and in turn indirectly associated with prosocial tendencies is consistent with previous findings linking maternal variables with youth prosocial tendencies in samples that were largely European American (e.g., Hastings, Utendale, & Sullivan, 2007). These patterns of relations suggest that mothers may be more influential than fathers on adolescents’ prosocial development. One possibility is that mothers spend more time with their teens than fathers and/or perhaps adolescents are more often exposed to their mothers, rather than fathers, as prosocial models (e.g., expressions of sorrow, comforting others). However, caution is needed in underestimating fathers’ influence on their adolescents’ prosocial tendencies. It may be that fathers’ influences are more indirect via other mechanisms or perhaps they moderate the relations between adolescents’ personal traits and prosocial behaviors. For example, perhaps fathers’ influence their teens’ prosocial tendencies through other forms of ethnic socialization such as by providing an ethnic role model, or the quality of relationship with their spouse such that more positive spousal relationships predict more prosocial behaviors in teens. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that Mexican American mothers play a prominent role in their youth’s prosocial development.

Of particular interest from understanding prosocial development within culture groups is the differential pattern of relations between traditional Mexican American values and U.S. mainstream values, to distinct forms of prosocial behaviors. These relations demonstrate heterogeneity within Mexican American groups and suggest that notions regarding the prosociality of Mexican Americans may be more nuanced than previously believed. For example, there is an accumulated body of research that suggests that Mexican Americans are relatively more cooperative than European Americans (see Knight, & Carlo, 2012). However, the present findings suggest that Mexican American teens may be predisposed to frequently engage in some forms of prosocial behaviors depending upon the degree to which they endorsed specific cultural values. Therefore, research on specific forms of prosocial behaviors may lead scholars away from simplistic notions of prosocial tendencies within and between culture groups.

Although this study provides valuable evidence that may help us understand how culture-related family processes may lead to more generalized prosocial tendencies among Mexican American youth, this study also has limitations. We were able to examine prospective relations with our longitudinal data, but we were not able to conduct strong tests of all of the hypothesized mediational relations because of the limited assessments we had of several variables. For example, because we did not assess prosocial tendencies until the 10th grade, we could not control for previous levels of prosocial tendencies in 7th grade. Although we did have parents’ and adolescents’ reports on their own cultural variables, a second limitation is our reliance only on self-report data. This creates a concern that the findings are subject to reporter bias (i.e., common method variance) and possible self-presentational biases. While possible, the different directions in the relations between the adolescent self-reports of prosocial tendencies and the variety of culturally related variables suggests that such biases are unlikely to be serious. Nonetheless, future studies using multiple methods (e.g., observational measures) are needed to fully address these possibilities. A third limitation is the reliance on a measure of prosocial tendencies that does not specify the recipient of these prosocial behaviors. However, prior research suggests that Mexican American youth who more strongly endorse familism values also score higher in empathic responding (Knight et al., in press), and empathic tendencies have been linked prosocial behaviors towards others in general (Eisenberg et al., 2006). Thus, it may be that familism may indirectly facilitate prosocial tendencies towards non-family members via increased empathic motivation. Future studies could benefit from the use of empathy measures and measures that assesses prosocial behaviors within and outside the family.

Despite the limitations, the findings show longitudinal evidence for a cultural transmission model of prosocial development in Mexican American adolescents such that maternal values are transmitted to their teens via practices. Moreover, the roles of cultural values and ethnic identity figure prominently as mediators of maternal, but not paternal, ethnic socialization practices and their adolescents’ prosocial tendencies. Of perhaps greater importance is the demonstrated utility of a culture-specific model of prosocial development that goes beyond traditional (generic) models of prosocial development that focus on sociocognitive or socioemotive traits (see Knight et al, in press). Culture-specific models that incorporate culturally-relevant predictors such as ethnic-based parental practices, cultural values, or ethnic identity may better account for individual differences in prosocial development within- and between-culture groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by NIMH grant MH68920 (Culture, Context, and Mexican American Mental Health). The authors are thankful for the support of Mark Roosa, Jenn-Yun Tein, Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, our Community Advisory Board and interviewers, and the families who participated in the study.

References

- Armenta BE, Knight GP, Carlo G, Jacobson RP. The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41(1):107–115. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi A, Schwartz SH. Values and behavior: Strength and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:1207–1220. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Tanner-Smith EE, Lesane-Brown CL, Ezell ME. Child, parent, andsituational correlates of familial ethnic/race socialization. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:14–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00339.x-i1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavior tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825. doi.org/10.1037/a0021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, de Guzman MRT. Theories and research on prosocial competencies among US Latinos/as. In: Villaruel F, Carlo G, Azmitia M, Grau J, Cabrera N, Chahin J, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology. Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Hausmann A, Christiansen S, Randall BA. Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:107–134. doi: 10.1177/0272431602239132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Knight GP, Basilio CD, Davis AN. Predicting prosocial tendencies among Mexican American youth. In: Padilla-Walker LM, Carlo G, editors. Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 242–257. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Knight GP, McGinley M, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. The multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors and evidence of measurement equivalence in Mexican American and European American early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(2):334–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00637.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman MRT, Carlo G. Family, peer, and acculturative correlates of prosocial development among Latinos. Great Plains Research. 2004;14:185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller PA, Shell R, McNalley S, Shea C. Prosocial development in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:849–857. doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.849. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Fabrett FC, Knight GP. Acculturation, enculturation and the psycholosocial adaptation of Latino youth. In: Villaruel FA, Carlo G, Grau J, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives. New York; NY: Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child’s internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:4–19. doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Utendale WT, Sullivan C. The socialization of prosocial development. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 638–664. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G, McCrae RR. Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-cultural research. 2004;38(1):52–88. doi: 10.1177/1069397103259443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1(4):200–214. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0104_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline TJB. Psychological testing: A practical approach to design and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(5):913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK. A social cognitive model of ethnic identity and ethnically-based behaviors. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1993;24(1):99–114. doi: 10.1177/0022022193241007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Carlo G. Prosocial development among Mexican American youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Carlo G, Basilio CD, Jacobson RP. Familism values, perspective taking, and prosocial moral reasoning: Predicting prosocial tendencies among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi: 10.1111/jora.12164. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, Bernal ME. The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1993;15(3):291–309. doi: 10.1177/07399863930153001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, German M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scales for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescents. 2010;30(3):444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Kagan S. Acculturation of prosocial and competitive behaviors among second-and third-generation Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1977a;8(3):273–284. doi: 10.1177/002202217783002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Kagan S. Development of prosocial and competitive behaviors in Anglo-American and Mexican-American children. Child Development. 1977b;6:1385–1394. doi: 10.2307/1128497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Kagan S, Buriel R. Confounding effects of individualism in children’s cooperation/competition social motive measures. Motivation and Emotion. 1981;5(2):167–178. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York City, NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate behavioral research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock CG. Development of social motives in Anglo-American and Mexican-American children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1974;29(3):348–354. doi.org/10.1037/h0036019. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim JY, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, Swanson DP. Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley M, Opal D, Richaud MC, Mesurado B. Cross-cultural evidence of multidimensional prosocial behaviors: An examination of the prosocial tendencies measure (PTM) In: Padilla-Walker L, Carlo G, editors. Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Vol. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, Bilsky W. Toward a psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:550–562. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.878. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda M, Shinotsuka H, McClintock CG, Stech FJ. Development of competitive behavior as a function of culture, age, and social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36(8):825–839. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.825. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of family socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond AB. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4(1):9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White RM, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Knight GP, Zeiders KH. Language measurement equivalence of the Ethnic Identity Scale with Mexican American early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31(6):817–852. doi: 10.1177/0272431610376246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.